7

The tribes of the south-eastern core

Catuvellauni/Trinovantes, Cantii and Atrebates

In the Late Iron Age, Britain can be divided into three broad zones: a core comprising the southeast which shared many cultural characteristics with the Continent; a periphery comprising an arc of coin-issuing tribes stretching from Dorset to Lincolnshire; and a beyond, that is the rest of Britain west and north of the periphery where coinage had not been introduced into the socioeconomic system. This threefold division provides a convenient way of considering the Late Iron Age and will form the basis for the next three chapters. In this chapter we will be concerned with the tribes of the core: the Trinovantes/Catuvellauni, difficult to distinguish from each other numismatically, the Atrebates and the Cantii.

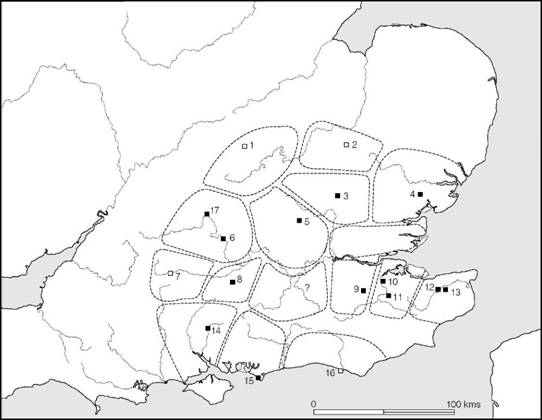

Much of this region, from Kent to the Fens and from the east coast inland to the Ouse valley and the Upper Thames, shared a number of cultural aspects with the Belgic areas of northern Gaul (Figure 7.1). Ceramic technology, burial rites, economy and socio-political structure showed only slight variation from one end of the region to the other. Nevertheless, behind this apparent unity lay two major tribal groupings – the Trinovantes/Catuvellauni and the Cantii – both recognizable through their distinctive coinages and both following discrete political policies in relation to each other and to the threat of Roman invasion. Given only the material and structural evidence it would have been very difficult to distinguish between them, yet the coin evidence and subsequent history leaves no doubt that very different political entities were involved.

Until comparatively recent times it has been conventional to refer to this cultural continuum as ‘Belgic’. The term was convenient in that it reflected the similarity of culture between this region and the Belgic area of northern Gaul, but it took with it the underlying assumption that the region had been settled by the immigrant Belgae referred to by Caesar. Since, however, serious doubt has been cast on this latter view, and a good case can now be made out for the undoubted similarities resulting from regular and intensive social and economic intercourse between the tribes on either side of the Channel, the word Belgic is best avoided. Instead the term Aylesford–Swarling culture will be used, which is defined on purely archaeological criteria without historical preconception.

The southern part of the core zone, which eventually became the territory of the Atrebates, shares a range of cultural similarities which are sufficiently different from the Aylesford–Swarling culture to require a separate name: here we will use the phrase Atrebatic culture since it is the culture of the historically attested Atrebates and does not extend beyond their normal boundaries.

Figure 7.1 Distribution of the Aylesford–Swarling and south Belgic cultures (source: author).

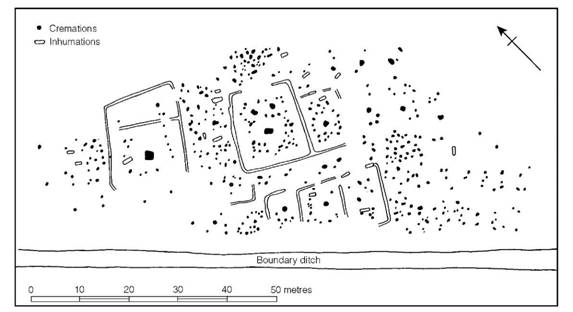

The Atrebatic and Aylesford–Swarling terminology reflects broad cultural groupings defined archaeologically, while the tribal entities based on coinage are essentially political constructs. Moving down the scale, a more detailed appraisal of the coin evidence allows the possibility of discerning, albeit dimly, smaller socio-economic units. The method used to define them is the attempted recognition of recurring patterns in successive coin distributions (Cunliffe 1981b). Though a rather inexact tool, and to a degree subjective, it does allow a number of zones to be postulated and the fact that most of these contain a major settlement site or oppidum in a roughly central position, lends credibility to their reality (Figure 7.2). These socio-economic zones provide a convenient framework for discussing the political geography of the individual tribes.

Figure 7.2 Socio-economic zones in the core region in the period 50 BC–AD 10. Black squares denote nucleated settlements with some evidence of urban functions; open squares are possible nucleated settlements: 1 Duston; 2 Cambridge; 3 Braughing; 4 Colchester; 5 Verulamium; 6 Dyke Hills; 7 Marlborough; 8 Silchester; 9 Oldbury; 10 Rochester; 11 Loose; 12 Bigbury; 13 Canterbury; 14 Winchester; 15 Selsey; 16 Castle Hill, Newhaven; 17 Abingdon (source: Cunliffe 1981b with modifications).

The Aylesford–Swarling culture: pottery and burials

The Aylesford–Swarling culture is named after two Kentish cremation cemeteries of La Tène III date excavated in 1886 and 1921 respectively. The relevant material was first brought together with a full discussion in a paper by Hawkes and Dunning published in 1931. The subject was reconsidered in the light of new finds, both British and Continental, by Birchall (1965) and received a further reassessment by Rodwell in 1976. The Continental background has been discussed by Hachmann (1976) since when there have been further considerations of aspects of the cultural complex (Stead 1976a; Tyers 1980; Thompson 1983).

The culture is characterized by a distinctive range of pottery, usually wheel-made, together with the rite of cremation in flat graves. The associated metalwork is invariably La Tène III. The classic statement of the distribution of the Aylesford–Swarling culture was provided by the distribution map of pedestal urns published by Hawkes and Dunning (1931, figure 7) and reproduced here as Figure 1.6 (p. 12), which shows the vessels concentrating in Kent, Essex, Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire and the London area with a few outliers further north and west. In the last sixty years many more sites have been discovered but the pattern has not changed significantly (Thompson 1982). Thus, in terms of the known tribes, the Aylesford–Swarling culture is the folk culture of the Catuvellauni, Trinovantes and Cantii.

D.F. Allen’s reassessment of Celtic coinage in Britain (1961a) showed that a number of Gallo-Belgic issues were reaching Britain from the end of the second century BC, and for a while it seemed reasonable to interpret this as evidence of a series of migratory movements from the Continent into eastern Britain, bringing an array of new cultural elements with them (Hawkes 1968). Several detailed studies, however, have failed to trace any substantial body of ‘Belgic’ material pre-dating Caesar’s invasion, though Birchall tentatively recognized a potentially early group of pottery. It is clear, therefore, that the developed culture (in the form defined here) is unlikely to have been introduced by Caesar’s invaders from ‘Belgium’ along with Gallo-Belgic coinage. The interpretation which best fits all the evidence is that a long period of social and economic intercourse existed between Britain and Belgic Gaul, allowing the possibility of limited movements of people, but that the Aylesford–Swarling culture proper developed after Caesar’s conquest of Gaul as the result of an intensification of trade between the eastern British tribes and their increasingly Romanized Belgic neighbours.

Before proceeding to a discussion of the individual tribal areas, some of the general characteristics of the Aylesford–Swarling culture must be considered.

Pottery is the most characteristic artefact (Figures A:31 and A:32, pp. 642 and 643). It is usually of exceptionally high quality, most of it being wheel-made with an assurance and similarity of design which suggests commercial production on a large scale by specialists who, in the first instance, may well have been immigrants. Tall, elegantly shaped urns with pedestal bases, conical urns, corrugated vessels and a wide range of elaborately cordoned and grooved bowls make up the bulk of the types, with butt-beakers, tazze, platters and lids occurring less frequently. Also relatively common are the coarser narrow-mouthed jars with their outer surfaces wiped or scored to create rough patterns. This type probably originated in an earlier period but takes on a new formality with the introduction of the techniques of wheel-turning.

After 15–10 BC the locally produced vessels were supplemented by imported fine wares from Gaul, Germany and the Mediterranean, including terra rubra and terra nigra platters, Gallo-Belgic butt-beakers, Arretine wares and eventually samian pottery, while from the middle of the first century BC wine was being imported in some quantity in large amphorae. Some local copying of the imports occurred, particularly of the Gallo-Belgic beakers and platters, and it is probable that the production of the pale fabric butt-beakers of Gaulish type had begun at Camu- lodunum before the invasion of AD 43.

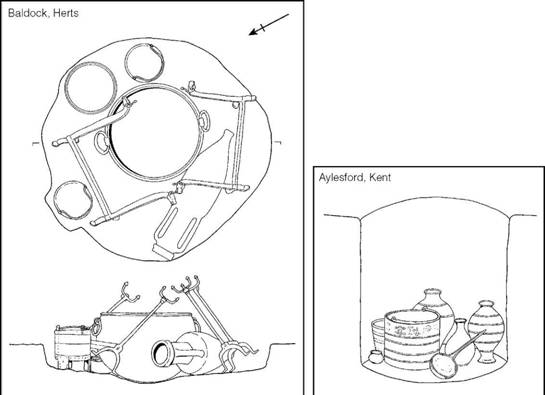

The culture is best known through its cemeteries and isolated burials, which form a significant part of the archaeological record. A few examples will suffice to demonstrate the range of burial rites. At Verulamium a typical cemetery has been excavated in its entirety, close to the nucleus of the Prae Wood Belgic settlement (Figure 7.3). Here no fewer than 463 individual cremations were discovered, usually placed inside an urn buried in a small pit, and often accompanied by one or more accessory vessels and by bronze brooches. Less frequently other grave-goods were buried, including mirrors, bracelets, keys, knives, shears, gaming pieces, spoons and toilet-sets – in fact, a range of personal belongings appropriate to both males and females. Some of the burials, richer than others, were heaped up on the floor of larger grave-pits, and several of these were placed in the centres of rectangular ditched enclosures containing poorer satellite burials arranged in a circle around the principal grave. The cemetery also produced eighteen inhumations, of which sixteen were unaccompanied. Judging by the quantity of imported Gallo-Belgic wares, which are unlikely to have arrived in Britain much before 10 BC, the cemetery must have been in use throughout the half-century before the invasion of AD 43.

Figure 7.3 The cremation cemetery at Prae Wood, Verulamium, Herts. (source: Stead 1969).

The large-scale excavation of the Verulamium cemetery allows the site to serve as a type example for La Tène III cremation cemeteries in general. To this category belong the two type- sites of Aylesford and Swarling, both of which are somewhat earlier than Verulamium. Neither site was excavated under modern conditions, and apart from the groups of grave-goods little is known of the general arrangement or plan of the cemeteries. At Swarling, however, two groups of cremations were found: an eastern group of nine and a western group of ten burials. Status distinctions were evident in the care with which some of the graves were dug, as well as from the number of accessory vessels provided and the occasional presence of fibulae. Grave 13 was outstanding in that the main burial was placed in an iron-bound wooden bucket together with two elaborate bronze fibulae, while standing around were six pottery vessels, no doubt once containing offerings of food and drink. Such elaboration suggests the burial of a person of wealth and status.

Elaborate bucket burials were also a feature of the Aylesford cemetery, where three such groups can be reconstructed (Birchall 1965, 243–9). Burial X contained a large wooden bucket bound with iron, together with six pots; burial Y was richer (Figure 7.4), consisting of a circular chalk-lined pit within which lay a bronze-plated bucket (Figure 7.5) containing the cremation and a fibula, a bronze oenochoe (jug) and a patella (pan), both of Italian manufacture, together with a number of pots. The third burial, Z, produced a bronze-mounted wooden tankard with bronze handles surrounded, apparently, by five or six pots. Since the Italian bronze vessels and the brooch from grave Y are types well known on the Continent in contexts dating to 50–30 BC, it may be assumed that the Aylesford burial dates to somewhere within the second half of the first century BC. The exact relationship of the three rich burials to the poorer cremations is unrecorded but the existence of circular settings of burials hints at the possibility of satellite arrangements comparable to those at Verulamium.

Figure 7.4 Bucket burials from Baldock, Herts., and Aylesford, Kent (sources: Baldock, Stead and Rigby 1986; Aylesford, A.J. Evans 1890).

An even richer bucket burial was found at Baldock, Herts., in 1967 during construction work (Figure 7.4): a subsequent excavation enabled details of the grave to be reconstructed. It comprised a roughly circular pit 1.6 m in diameter dug down into the solid chalk to a depth of 0.3 m in which had been placed a large bronze cauldron, two bronze dishes, two bronze mounted wooden buckets, two iron firedogs, an Italian Dressel 1A amphora and part of a pig. The cremated body, much of which was recovered from the cauldron, had been wrapped in the skin of a brown bear since phalange bones of the beast were found mixed with those of the human occupant. The Dressel 1A amphora might suggest that the burial belonged to the first half of the first century BC but the type does go on in use and a post-Caesarian date seems more likely.

Bucket burials, though few in number, occur widely in the south-east of Britain at Old Warden, Harpenden and Great Chesterford (Figure 7.5) as well as at Aylesford, Swarling and Baldock. Further afield they also occur at Hurstbourne Tarrant and possibly Silkstead in Hampshire and at Marlborough in Wiltshire (Stead 1971a). These peripheral burials presumably represent the adoption of Aylesford–Swarling traditions by the local Atrebatic aristocracy.

Figure 7.5 Reconstruction of bronze-bound buckets from Aylesford, Kent (left) and Great Chesterford, Essex (above) (scales: approx. ⅓). (Aylesford, photograph: British Museum; Great Chesterford, photograph: University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Cambridge).

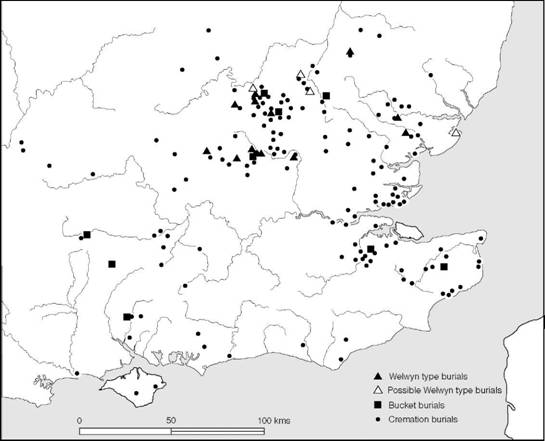

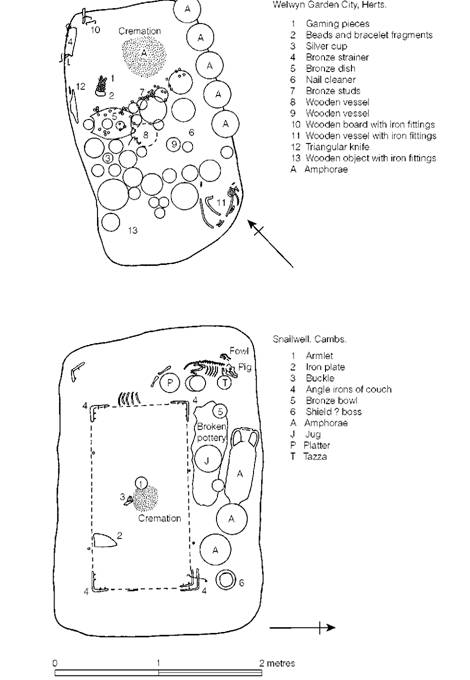

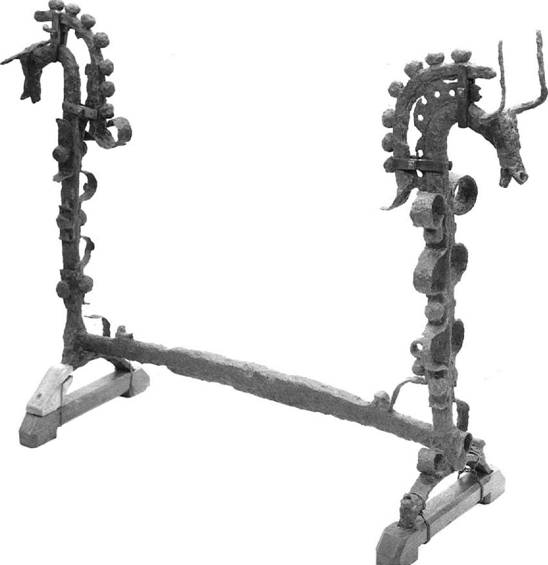

North of the Thames a group of exceptionally rich cremation burials (Figure 7.6) has been defined and named after the type-site of Welwyn, Herts. (Stead 1967). Six examples definitely belong to this group – Hertford Heath, Mount Bures, Snailwell, Stanfordbury, Welwyn and Welwyn Garden City – and a further eight sites in the same general area are possibly also of this kind. The Welwyn type burials may be characterized as cremations placed in large grave-pits with no covering mound (Figure 7.7). The pits contained a wide range of grave-goods, including at least one wine amphora (usually more, six being the maximum) and quantities of tableware, much of it imported. Some were provided with imported bronze vases, strainers and patellae, others with silver cups, while one produced imported glass dishes and containers. Clearly the dead person was being provided with sufficient food and wine to see him on his journey to the next world. Surprisingly, however, meat (or at least meat on the bone) is seldom found. Most burials contained a few personal belongings such as buckles, bracelets, beads and gaming pieces, but weapons are conspicuously absent. Iron firedogs (e.g. Figure 7.8), spits and in one case a tripod represent the dead man’s hearth furniture in several of the graves. The imported material, particularly the Italian bronzes in the earlier graves and the Gallo-Belgic and samian vessels in the later, allow the burials to be arranged in a chronological sequence spanning the century between the invasions of Caesar and Claudius. Welwyn-type cremations represent a tradition of aristocratic burial deeply rooted in the formative period of the Aylesford–Swarling culture north of the Thames.

The most impressive of the rich La Tène III graves in the Aylesford–Swarling region are those found at Lexden and Stanway, close to Camulodunum, and at Folly Lane, Verulamium. The Lexden burial, excavated in 1924, comprised an enormous oval burial pit 8.2 m long placed beneath a barrow 30 m in diameter. The excavation was only summarily published (Layer 1927) but has been recently reassessed, providing a far fuller picture of the grave and its contents (Foster 1986). The body had been cremated and placed in the pit together with an astonishing collection of grave-goods, including a bronze cupid, a boar, a bull, a griffin attachment, a pedestal for a statuette and a number of other copper alloy fittings and attachments. A suit of iron-chain mail, possibly once complete, and fitted with bronze buckles and hinges and silver studs, had been cut up and spread about the grave-pit. There were also silver mounts in the form of corn stems, a quantity of small silver trefoil attachments and a cast silver medallion displaying the head of Augustus moulded from a coin type minted between 19 and 15 BC. A large piece of gold fabric was found in close proximity to the cremation. Among the numerous iron fittings recovered were the bars of a folding stool. The grave was also furnished with a set of local pottery and a number of Italian wine amphorae – at least six of the Dressel 1B type and twice as many of Dressel 2–4.

Figure 7.6 Cremation cemeteries of the Aylesford–Swarling culture (sources: Whimster 1977; Fitzpatrick 1997a).

The grave-goods, taken together, would suggest a date of about 15–10 BC though burial may have occurred some little time later. The occupant of the grave was evidently a man of enormous wealth and status who chose a form of burial, under a barrow, more usual in Gaul than in Britain. His taste in Roman luxury objects and his ability to acquire them implies that he was a member of the Catuvellaunian/Trinovantian aristocracy thoroughly conversant with Roman taste. We will never know the identity of this British king but it is tempting to point out that, on the coin evidence, Tasciovanus died about 10 BC.

Figure 7.7 La Tène III chieftains’ burials (sources: Welwyn Garden City, Stead 1967; Snailwell, Lethbridge 1953).

Figure 7.8 Iron firedog from Chapel Garmon, Denbigh: hearth furniture of the type sometimes buried with the dead (scale: approx. 1/6) (photograph: National Museum of Wales).

The Lexden burial is typical of a particular class of aristocratic burials which involves two stages in the burial procedures: first the lying in state of the body surrounded by its rich grave- goods, followed by a second, closing, stage in which the body is cremated, the grave-goods are destroyed and the initial grave-pit is levelled. Not far from Lexden, at Stanway, another cemetery involving this same rite has been identified comprising five rectangular burial enclosures. The earliest burial, that of a female, is of about the same date as Lexden but the cemetery seems to have continued in use into the decade or two following the Roman Conquest.

The most spectacular of these high-élite burials was discovered at Folly Lane, Verulamium, within the area of the Late Iron Age oppidum. In this case the funerary shaft containing the destroyed grave-goods and the nearby pyre site where the cremation took place were fully excavated. The act of deposition seems to have taken place early in the post-Conquest period c. AD 55–60, and some time after this the pyre site was monumentalized with a Romano-Celtic temple. Folly Lane and Stanway are particularly interesting in showing the longevity of the late first-century BC funerary tradition.

From the foregoing summary it will be seen that the burial rite of the Aylesford–Swarling culture, while varied, was relatively consistent. It reflects a strong belief in the afterlife and it mirrors very clearly the rigid social stratification which must have existed. Simple cremations, bucket burials, Welwyn burials and the Lexden type represent four distinct levels in the social hierarchy from peasant through two tiers of ‘lordship’ to king.

It is not surprising that the ‘kingly’ burial tradition should be situated at the oppida of Veru- lamium and Camulodunum which were probably the paramount tribal capitals at this time. What is equally noteworthy is the cluster of rich chiefly burials on either side of the Chilterns in the valleys of the Lea, Ouse and Cam. What these may reflect are the centres of power of those able to command the trade routes between the periphery and the core (Cunliffe 1988b, 150–3). If so then the Welwyn burials may represent the vassal chieftains upon whom the paramounts – the dynastic rulers – built their power.

Within the territory of the Aylesford–Swarling culture there developed a series of large nucleated settlements which justify the use of the term urban or proto-urban. Their form and size vary considerably but for ease of discussion we shall divide them into three categories: enclosed oppida, territorial oppida and nucleated oppida. Figure 7.2 shows the distribution of the major sites of this kind for which the evidence is convincing. Individual sites will be considered in the following sections.

The Catuvellauni/Trinovantes

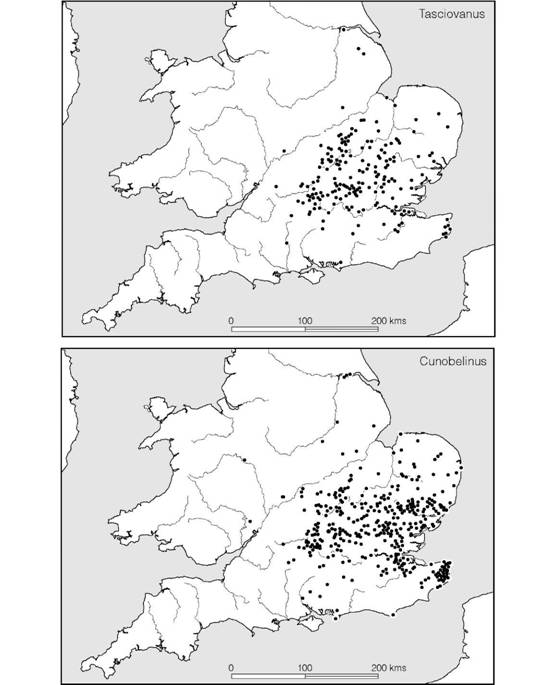

The Catuvellauni and Trinovantes were the two principal tribes occupying a wide swathe of territory north of the Thames including the modern counties of Essex, Hertfordshire and parts of Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Cambridgeshire and Suffolk. Some indication of the extent of their territory and influence is indicated by the distribution of the coins of Tasciovanus and Cunobelin (Figure 7.9). Since it is difficult to distinguish the coinages of the two tribes apart, they are here considered together.

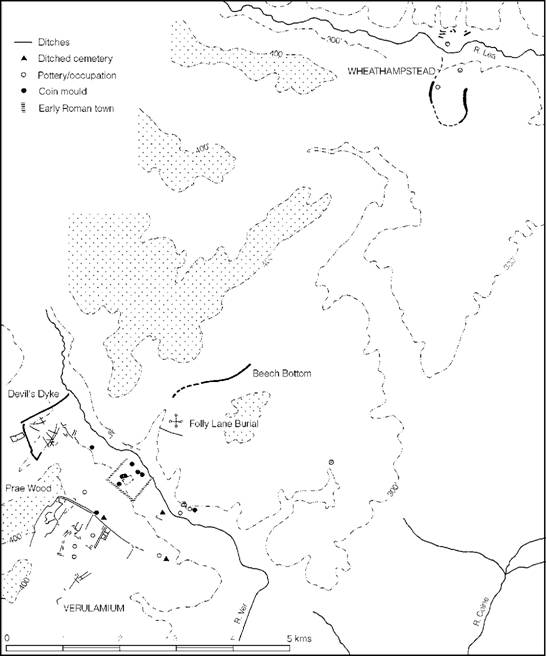

North of the Thames the extent of the Aylesford–Swarling culture is roughly coterminous with Trinovantian/Catuvellaunian coinage but the coin evidence allows the tentative recognition of a series of discrete socio-economic regions (Figure 7.2), in several of which large nucleated settlements, or oppida, have been identified. While it must be admitted that little is yet known of these oppida in Britain the work at Verulamium has defined the main characteristics of this type of site (Figure 7.10). The earliest nuclear settlement in the region lies on a gravel plateau above the River Lea at Wheathampstead, Herts., where massive earthworks flank at least three sides of an enclosure of some 36–40 hectares – the size of the average Romano-British town. Limited excavation within has demonstrated the presence of occupation spanning the latter part of the first century BC but apparently ending before 15–10 BC (if the absence of Gallo-Belgic vessels, which began to be imported at about this time, is regarded as significant and reliable). It has been suggested that Wheathampstead was the oppidum where Cassivellaunus made his last stand against Caesar. Caesar tells us that British strongholds in general were densely wooded spots fortified with ramparts and ditches and that Cassivellaunus’ stronghold was protected by forests and marshes and had been filled with a large number of men and cattle for their own protection. Wheathampstead would indeed fulfil these conditions, but the identification is unlikely ever to be proven and some doubt has been cast on the exact status of the site (Dyer 1976b).

Figure 7.9 Distribution of the coins of Tasciovanus and Cunobelinus indicating extent of Catuvellaunian/ Trinovantian territory and influence (source: CCI 2003).

The abandonment of Wheathampstead is apparently matched by the growth of Verulamium, 8 km to the south-west and occupying a similar plateau position above the River Ver in the area of what is now Prae Wood. Plentiful imports were found, showing that the site reached its maximum period of occupation in the first half of the first century AD. Instead of massive earthworks, the main inhabited area of the oppidum was enclosed by relatively slight ditches and palisades, altered on several occasions, within which lay the huts, drainage ditches and ovens of the settlement. Outside the boundary ditch flanking this nucleus was the cemetery referred to above. Other settlement areas must have existed nearby: one, found closer to the river beneath the Roman town, produced the debris of a Late Iron Age mint; another has been identified at Gorhambury to the north just within the Devil’s Dyke. Indeed it is possible that the Gorhambury and Prae Wood settlement areas are simply the outlying parts of the oppidum the core of which lies beneath the later Roman town. Another possibility is that settlement was dispersed rather than concentrated at a single nucleus. The Folly Lane burial overlooked the main settlement zone from the north bank of the Ver.

One further aspect of the local settlement pattern deserves consideration. From a point close to Wheathampstead to as far as the river Ver opposite the settlement at Prae Wood runs a massive defensive bank and ditch known as Beech Bottom Dyke, the staggered line of which is continued by a lesser earthwork, Devil’s Dyke, to the west of the river a little way north of the settlement. It seems probable that these banks and ditches form part of a series of dykes designed to defend and define the territory of the oppidum and its satellite settlements. As we shall see, systems of linear earthworks reach complex proportions at Camulodunum and in the Chichester region. The lack of such a development at Verulamium might be explained by the fact that the seat of centralized government had moved to Camulodunum early in the first century AD, relieving Verulamium of its political importance. If so, the Beech Bottom Dyke–Devil’s Dyke complex could be seen as an early stage in the development of territorial defences, arrested before the system could achieve its ultimate form.

Linear earthworks must be regarded as a new concept in defensive architecture arising late in the British Iron Age. Similar systems are recorded on the Continent. Tacitus (Annals ii, 19), describing the assembly of a Germanic tribe called the Cherusci, specifically mentions their choice of a location hemmed in by a river and forests which were surrounded by deep bogs. On the one side without natural defences the neighbouring tribe, the Angrivarii, had constructed a ‘broad earthwork as a boundary’. Here, surely, is a direct reference to large-scale linear defences erected to supplement natural obstacles in much the same way as the Beech Bottom complex makes careful use of the landscape.

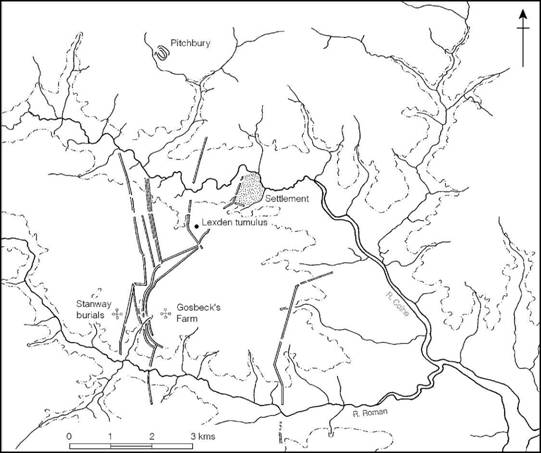

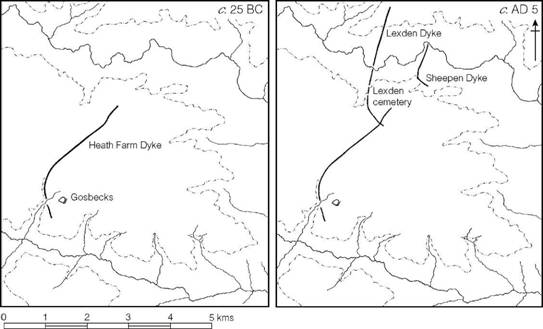

If Verulamium represents the beginnings of linear defensive systems, Camulodunum must demonstrate the ultimate development (Figure 7.11), for here a series of dykes, many of them laid out in straight lines running between the Roman river and the River Colne, carve out a territory of some 31 square kilometres. The system is so complex that more than one phase of construction must be involved. It is, in fact, possible to postulate an early nucleus at Gosbecks Farm where aerial photography has identified a large ditched enclosure of presumed Late Iron Age date followed by an elaborate Roman temple complex. Rodwell put forward a sequence involving six phases of development (Rodwell 1976, 339–59). His assessment was based largely upon topographical considerations. Following the publication of more archaeological data a simpler scheme has been proposed (Hawkes and Crummy 1995, 176–7) identifying two Late Iron Age phases. The first, they suggest, comprises Heath Farm Dyke and dates to c. 25 BC; the second saw the addition of Lexden Dyke and Sheepen Dyke some time around AD 5 (Figure 7.12). The rest of the system, they argue, was constructed at the time of the invasion, in AD 43, and in the twenty years or so following.

Figure 7.10 Late Iron Age occupation in the Verulamium–Wheathampstead region (source: Saunders and Havercroft 1982 with additions).

Within the Late Iron Age defended area a number of foci of activity have been identified. At Gosbecks Farm, we have already noted the rectangular enclosure: the Lexden burial and an associated cemetery were also enclosed by the Lexden Dyke. The Sheepen site, which has been examined by extensive excavation (Hawkes and Hull 1947), has yielded ample evidence of scattered huts of apparently circular and sub-rectangular form together with pits, ditches, the debris from a mint and masses of imported pottery. Here, evidently, lay a centre of some importance. The enormous quantity of imported wares found in one area has even suggested to the excavator the possibility that here was the actual residence of Cunobelin. Such an attribution, while possible, can never be proved.

While Verulamium and Camulodunum are undoubtedly the two principal urban centres in the territory of the Trinovantes/Catuvellauni, several other sites may be claimed to have urban status. Of these the best known lies in the vicinity of Braughing, Herts. Early occupation, beginning in the Middle Iron Age, was probably focused on the hillfort at Gatesbury Wood overlooking the River Rib but by the last decades of the first century BC occupation had spread to cover an area of some 100 ha. No enclosing dyke systems have yet been traced so at present Braughing must be classed as an unenclosed oppidum. Excavation, most extensively at Skeleton Green, has exposed evidence of rectangular timber buildings associated with chalk floors and gravel spreads spanning the period from c. 15 BC to the Roman Conquest.

A potentially similar site lies beneath the Roman settlement at Baldock, Herts.: occupation here began c. 50 BC. Since the extent of the pre-Roman settlement is not known it cannot yet be claimed to be of urban status though its subsequent Roman development is suggestive of its economic potential. Two other possible minor oppida have been claimed at Norsey Wood, Billericay, and Mount House, Braintree, but firm evidence is wanting.

The area of Hertfordshire between the River Lea and the Chilterns was particularly densely settled in the Late Iron Age, including as it does the sites of Verulamium, Wheathampstead, Welwyn, Baldock and Braughing (Bryant and Niblett 1997). Each of these nucleations will have performed one or more of a number of functions ranging from urban centres to rural markets. They show just how complex and densely settled was the landscape of the south-east at the time of the invasion.

Turning now to the outer fringes of the territory, extensive pre-Roman occupation existed beneath nucleated Roman settlements at Cambridge and Duston near Northampton; both are potential locations for oppida but in the absence of adequate publication the question must remain open. In the Upper Thames valley, at Dorchester, the evidence is somewhat more convincing. Here the massive earthworks of an enclosed oppidum known as Dyke Hills defend an area in the bend of the River Thames close to a major crossing point overlooked by the Early and Middle Iron Age hillfort of Wittenham Clumps. In the post-Conquest period a small Roman town developed just north of the oppidum. Further upriver, at the confluence of the Thames with the Ock, another massive Late Iron Age enclosure of some 33 ha, defined by three concentric ditches, has been identified beneath Abingdon. Like Dyke Hills it commands a major route node at a river crossing. A rather different kind of site lies to the north-west on the slopes of the Cotswolds. Here the North Oxfordshire Grim’s Ditch complex has the appearance of a territorial oppidum rather like Camulodunum but no concentrations of pre-conquest occupational activity have yet been identified.

Figure 7.11 Late Iron Age and early Roman settlement in the region of Camulodunum (source: Hawkes and Crummy 1995 with amendments).

Within the territory of the Trinovantes/Catuvellauni the reoccupation of hillforts does not seem to have been particularly common, but several sites on the Chilterns, like Wilbury, Ravens- burgh Castle and Cholesbury, produced finds of Aylesford–Swarling type. The same is true of the multivallate fort of Wallbury, Essex, the massive size of which, 12.4 ha, and its location suggest that it has more the characteristics of an enclosed oppidum than a hillfort.

Figure 7.12 The development of the Camulodunum dykes (source: Hawkes and Crummy 1995).

The history of the Trinovantes and Catuvellauni cannot yet be disentangled, though a number of general statements, based on an interpretation of the coinage, can be made (and have been summarized in the previous chapter). What all this means in terms of the relative fortunes of the different urban centres and their socio-economic territories is impossible to say except to stress the rise in power of Camulodunum. The vast size of the site, the richness of the Lexden and Stanway burials and the great mass of imported pottery found there leaves little doubt that Camulodunum had gained pre-eminence by the last decades of the first century BC and maintained its status until the Conquest when it was chosen by the Roman administrators to be the first of the coloniae of Britannia. Eventually, with better evidence from the other oppida and a more detailed consideration of the chronology of the rich burials, it may be possible to chart the changing fortunes of the smaller units that made up the larger territory over which Cunobelin became the ‘great king’.

The Cantii

The Cantii (Figures 7.13 and 7.14) evidently had a complex history. They were the first of the British tribes to issue their own coinage to serve as small change alongside Gallo-Belgic staters imported before the Caesarian campaigns. After the war they continued to issue their own coins until the turn of the millennium when, for a brief period, they came under the influence of the Atrebatic ruler Eppillus, before passing into the Trinovantian/Catuvellaunian sphere at about the time when Cunobelin took over leadership. At the time of Caesar’s invasions the Cantii had four kings (BG V 22), suggesting, but not proving, that they may have been divided into four self-contained kingdoms. Three distinct socio-economic units can be postulated on the basis of the coin distribution, centred respectively on the rivers Stour, Medway and Darent, and it is possible that the Weald or, alternatively, the region of East Sussex, constituted a fourth. That it may, indeed, have been East Sussex gains some support from the fact that the ceramic tradition of the area shared more with Kent and the Lower Thames region than it did with West Sussex. The separate nature of the three coastal units is further emphasized by the distribution patterns of different pottery fabrics: in addition to the ubiquitous grog-tempered wares, the Darent Zone used shell tempering, the Medway greensand tempering and the Stour flint tempering (Thompson 1982, 7). These regions, determined largely by geographical considerations, could approximate to the kingdoms which Caesar noted.

Figure 7.13 The territory of the Cantii (sources: various).

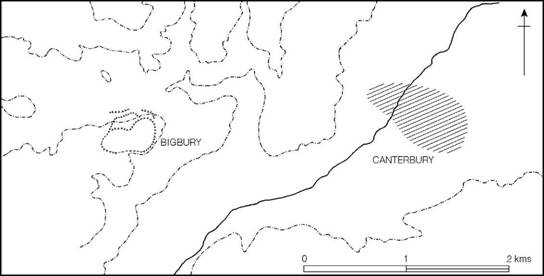

The principal ‘urban’ centres of the Cantii have been located, though excavation has been minimal. In the Stour valley the urban nucleus became focused on the site later to be occupied by Roman Canterbury, where occupation, in the form of rectangular huts and drainage gullies, has been found in the valley bottom on both sides of the river (Figure 7.15). Two kilometres to the west is the large hill-top fortification of Bigbury which conforms to the characteristics of an enclosed oppidum. It has produced an impressive range of metalwork, including a series of tools, horse- and vehicle-fittings, a slave chain and hearth fittings in the form of a firedog and a cauldron chain – objects which tend to emphasize the essentially aristocratic nature of the latest

Figure 7.14 Upper: Distribution of pottery of different tempers (source: I. Thompson 1982) shown against theoretical territories (source: author). Lower: Distribution of coins of the Kentish rulers (source: CCI 2003).

Figure 7.15 Late Iron Age settlement in the vicinity of Canterbury (source: author).

In the Medway valley two sites show urban attributions: an enclosed oppidum with associated linear earthworks at Loose and the site of the Roman town at Rochester where coin flan moulds have come to light. Here again the possibility of a move from one focus to the other is likely but unproven. Further west the high hill-top enclosure of Oldbury has produced some evidence of refortification and occupation in the Late Iron Age but excavation has been on too small a scale to gauge its nature.

The Aylesford–Swarling culture of Kent contrasts with that of the Trinovantes/ Catuvellauni in that there is little evidence of wealth accumulation in the post-war period. Apart from Ayles- ford and Swarling, rich burials are lacking and neither is of the status of the Welwyn graves. Moreover the Dressel type 1 amphorae, so prolific north of the Thames, are much rarer in Kent (Pollard 1991). The implication must surely be that in the period following Caesar’s campaigns the tribes of Kent were peripheral to the economic expansion enjoyed by those north of the Thames. It may be that they were deliberately excluded from trading contracts with the Roman province of Gaul because of their violent opposition to Caesar in 55 and 54 BC.

The Atrebates

The territory of the Atrebates lay, for the most part, south of the Thames, covering the modern counties of East and West Sussex, Surrey, Hampshire, Wiltshire and Berkshire. The tribe came first into historical perspective when Commius arrived in Britain to join his people already here, after fleeing from Caesar. Commius was a king of the Gallo-Belgic Atrebates and it was probably from this time onwards that his British followers were known by the tribal name. At the time of the Roman Conquest in AD 43 their chief oppidum was formally named Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester) but there was also an oppidum somewhere in the Selsey region which seems to have been the centre of a southern polity known as the Regni. Noviomagus (‘new market’), modern Chichester, may have replaced the Selsey centre after the invasion.

The name of the tribe or tribes over whom Commius established his authority is unrecorded but their identity and approximate location are recorded by the distribution of coin types minted in the period 75–50 BC on which Commius the founder and his immediate successor Commius (II) modelled their own issues. These have been called Atrebatic A and B (Van Arsdell 1989), though strictly pre- or proto-Atrebatic would be a more appropriate term. The distribution of these pre-war types (Figure 7.16) concentrated in the Middle Thames valley, Wiltshire, Berkshire and Hampshire with a scatter along the Sussex coast, whereas the coins of Commius (II) and his successors are found more commonly in the southern part of this region suggesting the possibility that the northern part of this region – the socio-economic territory based on Dyke Hills (Dorchester-on-Thames) and Abingdon – may have been absorbed into the Trinovantian/Catu- vellaunian sphere during the Gallic War. Some further expansion into the northern part of Atrebatic territory came in c. AD 35 when Epaticcus began minting coins at Calleva. His exact origins are uncertain. Though claiming a legitimate relationship to the Trinovantian/Catuvel- launian royal house, he continued to use an Atrebatic reverse type. However his origins and allegiance are interpreted, the fact remains that the northern marches of Atrebatic territory were unstable. The fluidity of boundaries between the two main power blocks is further shown by the brief ascendancy which the Atrebatic king Eppillus enjoyed over the Cantii between c. 5 BC and AD 10, after which he was replaced by the northern king Cunobelin.

The area of the original territory under Commius (II) corresponds closely to the distribution of the saucepan pot wares belonging to the Sussex, Hampshire and Surrey groups, hinting that some degree of cultural unity may well have existed in the pre-Caesarian period, stretching back into the second or third century BC. It was from this background that the new ceramic traditions of the Atrebates developed. Three new style-zones can be recognized, gradually emerging from indigenous traditions (Figure 7.17). These may be defined as an Eastern group, extending along the Sussex coastal plain and downs approximately to the Arun; a Southern group, covering the rest of Sussex and Hampshire west to the Test; and a Northern group, centring on Salisbury Plain and spreading north to the edge of the Thames valley.

The Eastern group (Figure A:35, p. 646), is characterized by globular jars with a narrow mouth and out-bent rim, some with flat bases and others with foot-rings. Another common type was the jar with a high shoulder, an upright or slightly everted rim and a foot-ring base. Decoration was carried out variously with shallow tooling, rouletting, stamping, painting and the addition of applied cordons, to create horizontal zones of swags and arcs, or sometimes simpler rectilinear zones. It is possible to trace many of the forms and decorative elements back to the preceding Late Caburn–Saltdean tradition, but some influence from the Aylesford–Swarling areas of Kent may be thought to be apparent in the foot-ring and cordoned types.

The Southern Atrebatic ceramic style (Figure A:34, p. 645), centred upon Hampshire and West Sussex, is typified by bead-rimmed jars with high shoulders and wide mouths, found together with high-shouldered bowls with simple upright rims, and necked jars often with a cordon at the junction of the neck and body. Less frequent (and occurring only in the first century AD) are local copies of Gallo-Belgic platters and butt-beakers. The Northern assemblage (Figure A:34, p. 645) is similar in many ways, but the bead-rimmed jars are frequently tightly grooved, and ovoid jars which hark back to the saucepan pot phase of the area occur together with rather larger quantities of Gallo-Belgic imports. There is nothing in either the Southern or Northern assemblages to suggest an intrusive element (except, of course, the imported Gallo-Belgic wares, which were presumably the result of trade). All the basic forms and decorative styles were already in existence in the preceding saucepan pot phase, the only difference being that the Atrebatic wares were, for the most part, wheel-turned. The apparent differences, then, are best explained in terms of the introduction of the technological innovation of the potter’s wheel rather than a significant folk movement, although it is possible that some ‘Belgic’ elements may have been introduced by the supposed immigrants arriving before the Caesarian wars (above, pp. 126-7).

Figure 7.16 Distribution of coins of the Atrebates (source: CCI 2003).

Figure 7.17 Distribution of Atrebatic pottery (source: author).

The three broadly defined ceramic zones probably owe their identity partly to the indigenous folk tradition and partly to the distributional ranges of the production centres, but it is conceivable that the regionalization in the later period also reflects a political fragmentation and realignment. On coin evidence it is possible to postulate the spread of Trinovantian/Catuvel- launian control over much of the north-west zone, centred particularly upon the valley of the River Kennet. It is in this region that the two south-eastern style burials were discovered, the bucket burial from Marlborough and the barrow cremation at Hurstbourne Tarrant. Furthermore, coins of Tasciovanus and Cunobelin are as common here as those of the later Atrebatic rulers.

The evidence from East Sussex is less dramatic, but we have already seen that the influence of the Aylesford-Swarling culture of Kent can be detected, and to this can be added the fact that a number of Aylesford-Swarling pots are found on the South Downs sites. More impressive, however, is the fate of the hillforts in the first century AD. Several of the East Sussex and Wealden sites, like those of Kent, show evidence of continuous occupation. This impression of unrest, and very probably an anti-Roman outlook, in the east contrasts noticeably with the south-western Atrebatic Zone of West Sussex and Hampshire, where not only were the old hill- forts abandoned but there is ample historical evidence of a pro-Roman alliance. Some support for the significance of this evidence is provided by the situation in the north-west zone, where again many of the hillforts were occupied and some refortified. In summary, it is not unreasonable to suppose that by the time of Verica the northern part of the original kingdom had come under the domination of dynasts from north of the Thames while the eastern part had realigned itself politically with the Kentish kingdoms, leaving only the central area in the hands of the original dynasty.

The coin evidence suggests that the greater Atrebatic region can be divided into six socioeconomic zones (Figure 7.2) in three of which urban settlements are known: Calleva, Venta and Selsey. In the easternmost zone no convincing centre has yet been identified, unless Castle Hill, Newhaven, or the Devil’s Dyke once served some central-place function. The Surrey-based zone, centred on the rivers Mole and Wey, is also without a known focus, but in the western zone in Wiltshire there is some evidence to suggest a major centre in the Marlborough district at Forest Hill close to the location of the Roman town of Cunetio.

The exact nature of the Selsey centre is a matter for some speculation, but in general terms there are marked similarities between this region and the site of Camulodunum. The nucleus of the settlement probably lay in the region of Selsey Bill, where extensive coastal erosion has removed most of the evidence apart from large quantities of coins and fragments of gold washed up on the shore. The entire peninsula is protected by a series of dykes running across the gravel terrace between the valleys of the south-flowing streams, while the lines of the valleys themselves are further strengthened by north–south earthworks (Figure 7.18). As the result of a detailed survey, Bradley (1971a) has postulated three major phases of defence protecting progressively smaller territories, though the intention throughout was clearly to defend the whole peninsula between the Lavant and the streams flowing into Bosham harbour – that is, to protect the farmland belonging to the oppidum as well as the main nucleated settlement and its satellite farms. It was within the northern part of this territory that the Roman town of Chichester (Noviomagus Regnensium) was subsequently built, together with the large palatial building 1.6 km away at Fishbourne, which has tentatively been ascribed to the client king Togidubnus. Several settlements are known within the area, as well as a cremation cemetery at Westhamp- nett.

The nucleus of the northern centre, Calleva, was subsequently buried beneath the Roman town of Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester) but its existence has long been attested by the discovery of large numbers of Celtic coins together with quantities of pre-Roman pottery, including imported amphorae, Gallo-Belgic wares and Arretine vessels (Boon 1969). A major campaign of excavations beneath the Roman basilica has exposed evidence of the settlement layout (Fulford and Timby 2000). The site lies on a tongue of gravel projecting between West End Brook and the Silchester Brook (Figure 7.19). Numerous earthworks exist in the area, but none can be dated with precision though a date in the second half of the first century BC seems likely. If this is so then it could be that enclosure began at the time when Commius I or Commius II was establishing himself in the northern Hampshire–Berkshire region. The lengths of massive earthwork which command the approach to the promontory are likely to belong to a subsequent, but pre- Roman, phase. They are similar to the dykes comprising the territorial oppida at Selsey and Camulodunum.

Figure 7.18 The entrenchments in the vicinity of Chichester, Sussex (source: Bradley 1971a with additions).

The basilica excavation has defined two major phases of occupation, the first dating c. 25– c. 15 BC, represented by a number of gullies belonging to circular houses and wells, and the second beginning c. 15 BC when a road grid was laid out to serve a series of rectangular timber buildings. This was presumably the capital of Tincommius and Eppillus, and it was from here that Eppillus minted his coins with the mint marks CALLEV and CALLE. The finds recovered show that Calleva was a high-status site enjoying quantities of coins and metalwork together with an impressive range of imported pottery.

An analysis of the pottery has suggested that in the later period Calleva shared in the economic systems of eastern Britain, a fact further emphasized by the density of coins of Tascio- vanus and Cunobelin in the region. It is tempting to see this as an economic reorientation coming about in the last decades of the first century BC which eventually, c. AD 35, led the Tri- novantian leader to establish his authority over the region and mint his coins from the capital.

The third oppidum, at Venta Belgarum (Winchester), lies largely beneath the Roman town (Figure 15.38, p. 404). Intensive occupation of the valley side began in the second to first centuries BC during the currency of saucepan pots. At this time a bank and ditch were constructed to enclose on the north, west and south sides an area in excess of 14 ha. The eastern limit is not known, but it is conceivable that the earthworks simply ran down the hill and terminated on the edge of the marshy river valley. Occupation within the enclosure was probably continuous, but by the first half of the first century AD the nucleus had moved further towards the river, where fragments of coin moulds and quantities of Gallo-Belgic pottery suggest a settlement of some importance.

Figure 7.19 The site of Calleva, Hants (sources: Boon 1969; Fulford 1986).

The three Atrebatic oppida so far considered may all have begun to be occupied in the pre- Caesarian period, but their siting and subsequent development show that they were not hillforts in the strict sense of the word. Some earlier hillforts did, however, continue to be maintained (Figure 7.20). At Bury Hill, Hants, the original enclosure was remodelled in bivallate form, while at Boscombe Down West, Wilts., and Suddern Farm, Hants, bivallate enclosures of similar type were constructed in the first century AD on earlier sites previously occupied. Chisbury, Wilts., may also belong to this class. Elsewhere in Wiltshire at Yarnbury, Ebsbury, Oldbury, etc., the earlier defensive circuits continued in use, but nothing is known of any refortification. In all probability the occupation within these old enclosures was of a domestic kind and need have been little more than peasant farms making use of the old earthworks as convenient boundaries. This was clearly the case at Danebury and Balksbury. The large double-ditched enclosures of Boscombe Down West type are altogether different and may represent the residences of the tribal élite. The excavations at Suddern Farm suggested that the settlement in this period may have been of high status.

Figure 7.20 Atrebatic enclosures (sources: various).

Rather less is known of the settlement sites of this period, largely because excavations have seldom been on a large enough scale to uncover a reasonable sample of the ground plan, but at Worthy Down and Owslebury in Hampshire and at Casterley in Wiltshire substantial areas have been exposed, together with sufficient evidence to demonstrate a continuity of occupation from the time of the saucepan pot tradition. These sites comprise complexes of ditched enclosures designed to create corral space as well as habitation areas (p. 248).

Burial rites within the Atrebatic area varied considerably. At Owslebury and St Lawrence, Isle of Wight, inhumation burials of warriors with their swords and shields were recorded in La Tène III contexts. In the northern part of the region, however, the Trinovantian/Catuvellaunian style of cremation was practised, for example at Marlborough and Hurstbourne Tarrant, and over most of the rest of the area cremation was the general rule. The most thoroughly excavated and published of the cemeteries is that found at Westhampnett, West Sussex, to the north-east of Chichester. Here a ritual site comprising 161 cremations, several pyre sites and four structures identified as possible shrines were located, representing activity over a period of some four decades, c. 90–50 BC. The early date for the beginning of the cemetery may suggest that the rite was introduced directly from neighbouring regions of northern Gaul, perhaps as the result of an influx of Belgae into the Solent region around 100 BC, and was, therefore, separate from the cremation tradition of the Aylesford–Swarling tradition.

Summary

In the Late Iron Age the core zone of south-eastern Britain was dominated by two dynastic kingdoms, the Trinovantes/Catuvellauni north of the Thames and the Atrebates (and their immediate predecessors) to the south, with the lesser tribe, the Cantii of Kent, lying between. The north–south divide was an unstable one: the numismatic evidence suggests that the northern dynasty established authority over the Middle Thames region and eventually dominated Berkshire and northern Hampshire, and the entire territory of the Cantii. To what extent this expansion of influence was purely economic or involved political dominance it is difficult to say. At any event the classical writers believed that the British tribes were in a state of perpetual warfare, and refugees from the various royal households fleeing to the emperor must have encouraged this view.

The cultural development over much of the core area followed similar lines: the skills of the metalworkers increased and there was a marked technical improvement in pottery manufacture with the introduction of the potter’s wheel. There is also evidence for the intensification of production not only in pottery-making but in salt extraction on coastal sites and ironworking in the Weald. This increase must, to some extent, have been encouraged by the development of trade with the Continent through the east coast ports. In return luxury goods from the Roman empire poured in and were used in complex patterns of exchange to maintain, and enhance, the status of the aristocracy. The concentration of luxury goods in Essex and Hertfordshire, now preserved mainly in élite burials, provides a clear indication of where the centres of power lay.

In the southern zone the Atrebates and the Cantii benefited little from the wealth-generating trade: amphora burials of Welwyn type are unknown and even lower-status bucket burials are rare. One possible explanation for this is that, in the political settlement which followed Caesar’s campaign in Britain, the southern tribes were regarded as hostile and trading monopolies were established to reward Roman allies in eastern Britain. Some such explanation is needed to account for the decline in the wine trade originally passing through Hengistbury on the Solent coast, and its rapid development, in post-war times, now focusing on the Essex coastal ports.

In spite of the apparent disparity in trading opportunities, large nucleated settlements (oppida) developed in all parts of the south-east, usually on route nodes where the movement of goods could be more easily controlled. At many of these sites coins were minted, and there is evidence of such a range and intensity of activity that we can fairly regard them as serving urban functions. Proto-urban or urban centres and complex systems of coinage involving a set of denominations show that the south-east was fast acquiring a market economy at the moment when Rome struck.