15

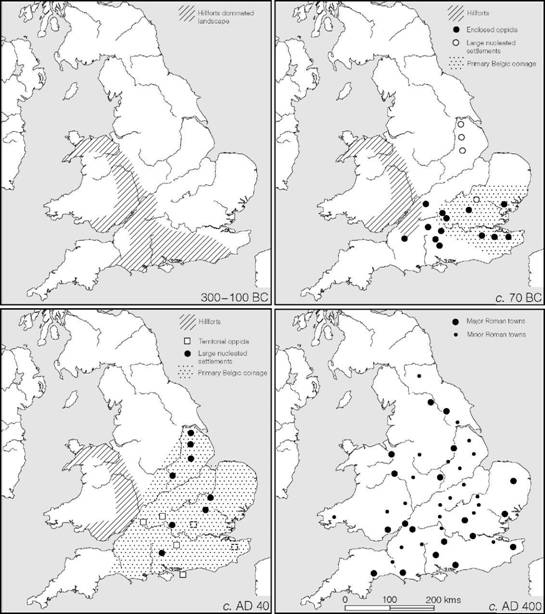

The development of hillforts and enclosed oppida

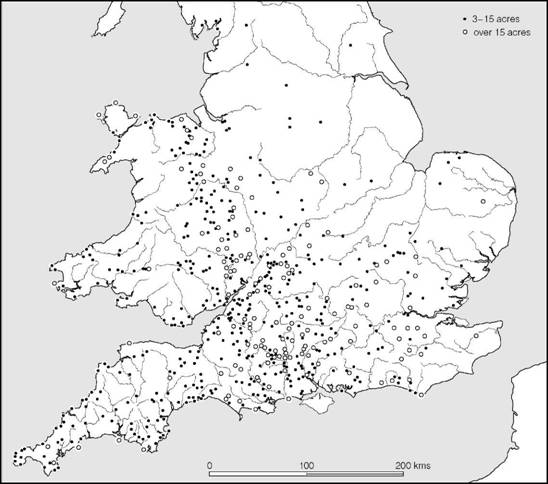

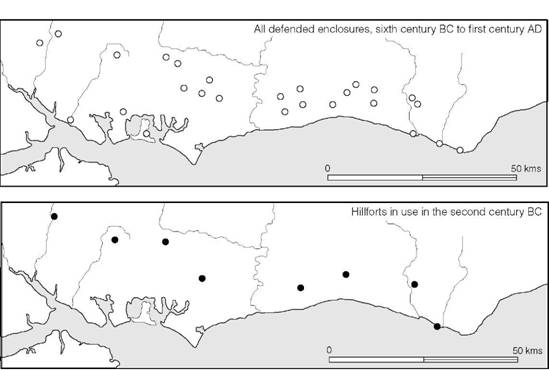

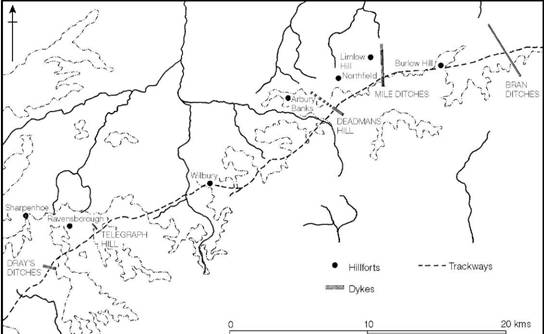

England, Scotland and Wales together can boast about 3,300 structures classed loosely under the heading of hillfort and other defended enclosures (Hogg 1979). Many more than half are small sites of 1.2 ha or less which need be little more than defended homesteads: these include the rounds of the south-west peninsula, the raths of south Wales and the numerous homesteads and small settlements of eastern Scotland. As a broad generalization it may be said that the bulk of the hillforts proper are concentrated in central southern England (Figure 15.1) in a broad band running from the south coast to north Wales. To the west the settlement pattern is dominated by the strongly defended homesteads while to the east single family farmsteads and undefended hamlets are the norm. Hillforts are essentially a specialized form of settlement: their size, complexity and siting suggests that they represent the communal effort of a large sector of the social group working under the coercive power of the leadership. If this is so then they represent a level of social organization above that of the farmstead and hamlet and may legitimately be considered as a separate phenomenon.

This said, some words of caution are necessary. The word ‘hillfort’ is a portmanteau term covering a variety of fortifications of differing sizes spanning 800 or 900 years. Given such broad parameters it is only to be expected that there will be, hidden within their structures, evidence of a range of functions varying with time and geographical location. Such variety can only dimly be appreciated because of the relative paucity of well-excavated data. While a large number of hill- forts have suffered some form of excavation, very few have been examined on a large enough scale to enable their developing functions to be properly identified. In consequence, while theories and generalizations abound, hard evidence is difficult to come by.

The vast majority of those hillforts which have been ‘excavated’ have had their ramparts sectioned and sometimes their gates uncovered, but little else. In consequence there is a fair body of evidence reflecting upon hillfort defence which, with the advent of radiocarbon dating, can be presented in a broad chronological perspective. A summary of the present state of knowledge will be given first. Using this evidence in conjunction with topographical and locational studies it is possible to offer, for some regions, a general assessment of hillfort development throughout the first millennium BC. This can be further enhanced with much rarer evidence derived from the sampling of hillfort interiors to throw some light on questions of function and social organization. Such an approach, focused on central southern Britain, will also be attempted later in this chapter.

The next level of abstraction – an assessment of the changing social and economic functions of hillforts – depends upon evidence derived from very few large-scale excavations. Some general comments will be offered in this chapter but the question will be returned to later in a rather broader context in chapter 21.

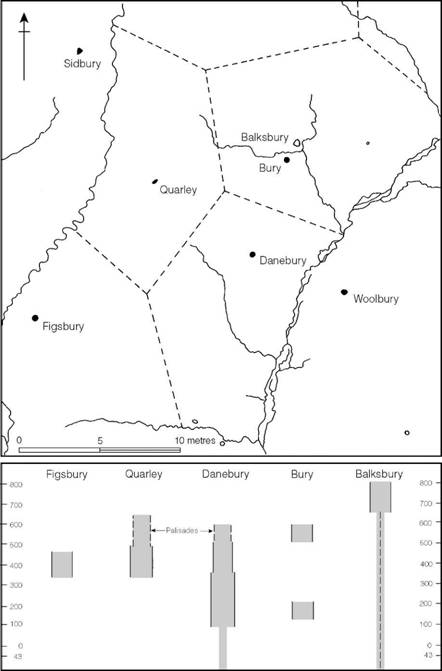

Figure 15.1 Distribution of hillforts in southern Britain (source: Ordnance Survey, Map of Southern Britain in the Iron Age).

Finally we will consider the end of the hillfort phenomenon and the emergence of larger and more complex oppida.

The structure of hillfort defences

Between 100 and 200 hillforts have had their defences sectioned, exposing the structure of their ramparts. Unfortunately, many sites were dug before the subtleties of internal timber-work were understood and frequently the trenches were too narrow and too few to provide decisive evidence bearing on the presence or absence of internal structure. However, a number of sites have yielded useful results and this evidence can be synthesized into a general pattern of development relevant to most areas of the country (Avery 1993).

Earth and timber structures in England and Wales

Palisades

One of the earliest kinds of defensive barrier employed on sites of hillfort size was the palisade of close-set timbers embedded in a continuous foundation trench without ditches or the banking up of spoil behind. This is clearly the same technique as that used on the smaller settlements (discussed above, pp. 239–41), which developed out of a tradition of fencing going back to the beginning of the first millennium or earlier. Wherever excavation has been adequate, palisades, if they occur, can be shown to precede earthwork defences. At the Breiddin, Montgomery, a double palisade bedded in a shallow bank lies at the beginning of a complex development, and the evidence of associated finds and radiocarbon determinations suggest that a ninth- or even tenth- century date might not be out of place. At Moel y Gaer, Flints., one or more palisades are thought to pre-date a long development sequence and are probably related to a phase of settlement for which a date in the eighth or seventh century is indicated by radiocarbon determinations. A similar succession of palisades also preceded the construction of a rampart at Dinorben. The palisade at Blewburton Hill, Oxon., antedates by some time the construction of a timber-box rampart, and the same interpretation is possible for the foremost palisade at Bindon Hill, Dorset, and Hod Hill, Northants. At Woodbury Castle, Devon, Skelmore Heads, Lancs., Wilbury, Herts., and Eddisbury, Cheshire, short lengths of early palisades have been found, again in early contexts pre-dating the subsequent developments on these sites.

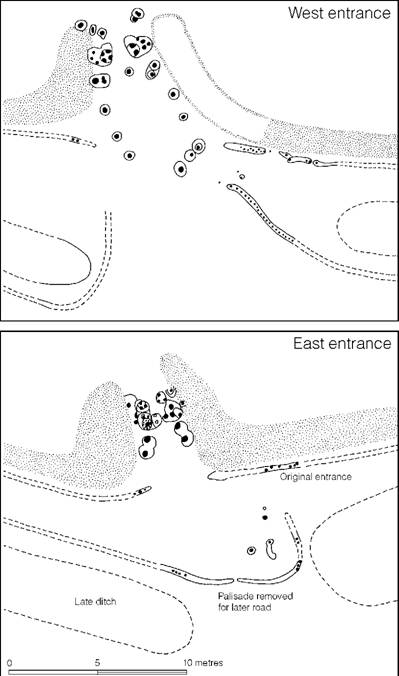

Although in the examples noted above the later defences generally follow the earlier palisades at the points excavated, there is no positive proof that the lines were coincident throughout. The rather more extensive excavations at Hembury, Devon, have however demonstrated that here the defences of the later fort follow what appears to be an earlier palisade more or less exactly on at least two sides of the circuit (Figure 15.2). Admittedly, the interpretation of the sequence is not straightforward but the outer palisade would appear to be the earliest feature, since at the position occupied by the later east entrance it was refilled at the point where the new roadway crossed it. The inner ‘palisade’ may, however, be the fronting timbers of the earliest box rampart (Todd 1984). The implication here, then, is that the construction of the earthwork defences followed hard upon the abandonment of the palisade. Both the later entrances were placed close to the sites of the palisade entrances, but the digging of the later ditches has obscured some of the details. Even so, the outer palisades can be seen to curve back inwards and at the east entrance there is some evidence to suggest a timber structure within the incurve not at all unlike the towers of the second-period gates at Harehope in Peeblesshire.

Large palisaded enclosures can therefore be seen generally to precede hillforts, sometimes by a considerable period of time. Few absolute dates can yet be given but it is known from the smaller palisaded homesteads of the north that the method of defence was being practised in the eighth century (pp. 311–20) and the finds from the Breiddin point to an origin here going back a century or two earlier, an indication supported by the evidence from Moel y Gaer.

Figure 15.2 The palisaded enclosure at Hembury, Devon (source: Liddell 1935a).

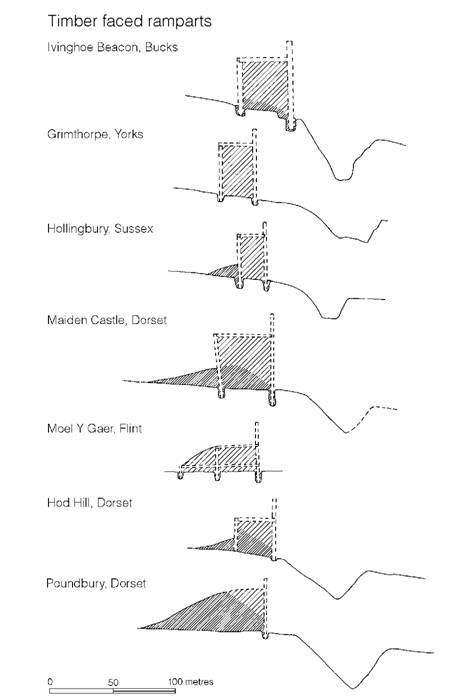

The Ivinghoe Beacon style of timber strengthening (Figure 15.3)

In parallel with the palisaded enclosures a second type of defence developed, known at present from Ffridd Faldwyn, Montgomery, Ivinghoe Beacon, Bucks., Grimthorpe, Yorks., Castercliff, Lancs., and Dinorben, Denbigh. At Grimthorpe rubble and soil from a relatively shallow U- shaped ditch was retained between two rows of timber about 2.4 m apart, the timbers in each row being placed at about the same spacing, thus forming a rough grid which would have allowed cross-bracing to keep the structure rigid. Between the verticals of both the back and front rows one must imagine a close boarding of planks or halved timbers to prevent the rubble fill from spilling out. Although dating evidence is by no means decisive, it is now becoming clear that simple box ramparts probably pre-date the conventional beginning of the Iron Age. At Rams Hill, Berks., a radiocarbon series suggests that this type of construction should be dated to the twelfth century BC. The box ramparts at both Ffridd Faldwyn and Dinorben lie at the beginning of long development sequences: at Dinorben a series of radiocarbon dates from the most recent excavation (Guilbert 1979a, 1980) range from the eighth to the sixth centuries. Grimthorpe provided two early dates for bone samples recovered from the partially silted ditch spanning the thirteenth to the eighth centuries. The dates from Ivinghoe Beacon extend from the eighth to fifth centuries but the metalwork from the fort lies within the eighth to seventh centuries. At Hunsbury, Northants, the box rampart was added in front of an existing palisade which remained in use. Radiocarbon dates suggest construction between the eighth and fourth centuries BC. Finally the box rampart from Castercliff produced radiocarbon dates suggestive of a seventh- or sixth- century construction. Taking this evidence together, there is a degree of consistency about the overall pattern, suggesting initial occupation in the twelfth to sixth centuries. Thus the earliest hillforts in Britain must have developed in parallel with those of the European Urnfield cultures. Strictly, the box rampart could be thought of as a double palisade, of the type well represented in northern Britain (pp. 313–15), filled with earth and rubble. The nature of this relationship both structurally and chronologically remains to be further examined.

The Hollingbury Camp style of timber strengthening (Figure 15.3)

A simple development following the rubble-filled timber wall of Ivinghoe Beacon type was the addition of a sloping rampart behind the inner face of the inner row of timbers. This would have provided two additional advantages: ease of access at all points and an added strength and rigidity. While at Hollingbury Camp, Sussex, the bank was slight – barely 2.7 m wide – backing a timber wall of the same width, in the first phase of Danebury, Hants, the 2.1 m wide timbering was backed by a far more substantial structure almost 9 m wide. At Maiden Castle, Dorset, the timber structure of period I was 3.6 m wide, with a bank of equivalent width behind, standing to a maximum height of 1.4 m, while at South Cadbury, Somerset, the earliest rampart measured in total width 4.4 m, the distance between the two faces of the timber structure being only 2.2 m. At Blewburton, Oxon., the total width of the rampart was 6.4 m, the distance between the two timber rows being 4.0 m. While at Winklebury, Hants, the overall width of the rampart was about 3 m while the two timber faces were only 2 m apart. Clearly, there were considerable variations in proportion.

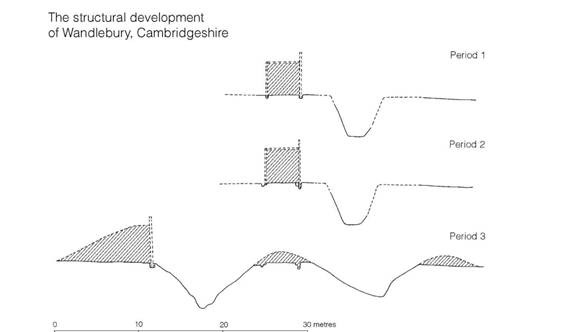

Wandlebury, Cambs., is a useful example in demonstrating a sequence of development (Figure 15.4). In the first period a box-type rampart was constructed with timber faces 4.0 m apart, the front timbers being placed at 0.76 m intervals, and those of the back face even closer. Whether or not a backing ramp was built will never be known, since a later ditch would have dug it away. In the second phase the rampart was rebuilt 4.3 m wide, with the timbers in both rows set at 2.7 m centres, again possibly with a backing rampart. In the third major phase a totally new rampart was thrown up behind the original work, and was fronted by a ditch. This third-period work was constructed in a style to be described below as the Poundbury style. Thus, what was presumably a Hollingbury type of rampart had an extended use at Wandlebury. Its replacement is, however, a reminder that timber had a relatively short life and major rebuilding would have had to be carried out perhaps as often as every decade or two if the defences were to be kept in good order.

Figure 15.3 Comparative sections of box ramparts and their derivatives (sources: Ivinghoe Beacon, Cotton and Frere 1968; Grimthorpe, Stead 1968; Hollingbury Camp, E.C. Curwen 1932; Maiden Castle, Wheeler 1943; Moel y Gaer, Guilbert 1975a; Hod Hill, Richmond 1968; Poundbury, Richardson 1940).

The dating of this type of construction technique is tolerably well known. At Hollingbury Camp pottery of the seventh to fifth centuries has been found within the fort, but not in direct relationship to the rampart, while at most of the other sites the associated material lies consistently within the sixth- to third-century range.

The Moel y Gaer style of timber strengthening (Figure 15.3)

Area stripping of a length of the rampart of Moel y Gaer has produced startling results. Here the earliest rampart was faced with upright timbers 0.6–0.9 m apart, the gaps between being infilled with dry-stone walling, usually incorporating large orthostats. The inner row of timbers, which the excavator considers was merely a curb and an anchor for horizontal lacing timbers, was 6 m from the outer row, but a more widely spaced middle row was found, probably representing the main vertical supports to which the front revetting was tied. The rampart was sufficiently well preserved to suggest that it stood originally to a height of 1.7 m, above which there would probably have been a breastwork. Careful excavation of the rampart body showed that it had originally been divided, front to back, probably by hurdles, to create a series of compartments which were filled with different tips of rubble. A cellular structure of this kind would have been particularly valuable in containing the rampart when repairs to the front face became necessary.

The Moel y Gaer style of rampart construction differs from the typical Hollingbury style in that the main anchor timbers for the front face were widely spaced and the tail of the rampart was revetted with close-spaced verticals which may also have served to give a rigidity to the timber structure. Had a substantial length of rampart not been excavated, it is unlikely that the middle row of structural timbers would have been found. With this in mind it is possible that the rampart of Buckland Rings, Hants, should be placed in this category. Here limited excavation suggested two rows of timbers 5.8 m apart, set within an earthwork of 9 m width overall. The distance between the timber rows is excessive for simple cross-bracing, but if a middle row of more widely spaced timbers had occurred, as at Moel y Gaer, the problem would not have existed. In this context, Breedon-on-the-Hill, Leics., should also be considered. In the first phase, the fronting fence was of closely spaced timbers, with the tail of the rampart 7.6 m away, revetted by individually bedded posts. The excavation trenches were too narrow to have been sure to have picked up a middle row of widely spaced timbers, if this had existed, and no cross-bracing was noted, but superficial similarities to Moel y Gaer suggest that Breedon-on-the- Hill may well have been of the same type. Caesar’s Camp (Wimbledon), Surrey, poses a similar problem. Two narrow sections observed under rescue conditions brought to light evidence of front and rear timbers 8.2 m apart, but no middle row was noted. Once more the distance apart is probably too great for simple cross-bracing and a more complex structure of Moel y Gaer type might be anticipated.

The construction of the Moel y Gaer rampart post-dates two samples dated by radiocarbon to between the eighth and sixth centuries.

Figure 15.4 The development of the defences at Wandlebury, Cambridgeshire (source: Hartley 1957).

The Hod Hill type of timber strengthening (Figure 15.3)

The first phase of the defences of Hod Hill, Dorset, possessed an internal structure at present unique. A rampart some 9.7 m wide was fronted by a continuous palisade trench in which were placed vertical timbers, no doubt backed by horizontal timber cladding. Within the body of the mound was found a second row of individual timbers, the bases of which did not penetrate the natural subsoil; to these the front fence would presumably have been anchored. The defences differ from the more normal Hollingbury Camp type in that the inner timbers were supported only by the spoil of the rampart itself. In an excavation less skilfully observed, they might well have passed unnoticed.

It is tempting to see the constructors of Hod Hill adapting time-honoured building methods in the realization that the inner timbers were needed only to anchor the fronting fence, post-holes specially cut into the bedrock being no longer required. Strictly the Hod Hill structure is only a variant of the Moel y Gaer style.

The Poundbury type of timber strengthening(Figure 15.3)

The logical development following the breakthrough at Hod Hill was to modify further the nature of the inner timbering. At Poundbury, Dorset, excavations demonstrated a 9 m wide rampart fronted by a palisade of closely spaced timbers 1 m apart. No trace of internal timber-ing, either vertical or horizontal, was seen. It may, of course, be that the trenches were so sited as to miss inner verticals, but this is unlikely. A more reasonable explanation is that the front face was attached only to horizontal beams embedded within the body of the rampart: these would have been extremely difficult to trace and would have appeared only under ideal conditions. It is inconceivable that the fence could have withstood the thrust without some such back-pinning. As with the Hod Hill type of construction, it could be that the Poundbury type was simply a variant of the Moel y Gaer style.

The third phase of Wandlebury, Cambs., which demonstrably replaces the rampart of Holling- bury type, was of a similar construction. The same technique appears to have been adopted at Yarnbury, Wilts., Bury Hill I, Hants, Titterstone Clee, Salop, and Cissbury, Sussex.

The dating of the Poundbury technique is difficult to ascertain with precision: at Wandlebury it is later than the Hollingbury style and associated with pottery which could centre upon the sixth to fourth centuries. The evidence from the other sites, such as it is, does not conflict with this broad generalization.

The glacis style

In the constructional variations described, the overriding consideration was to provide a vertical wall of timber confronting the outside world, usually protected by a ditch dug some metres in front of it. Yet, however the backing structure was modified, the basic flaws in design remained: the timber would soon rot and would have to be replaced (a difficult task in such circumstances); it could easily be fired by an enemy; and the gradually crumbling lip of the ditch would eventually loosen the fronting timbers. Nor should we overlook the considerable labour involved in providing timber for defensive circuits (Manning 1999).

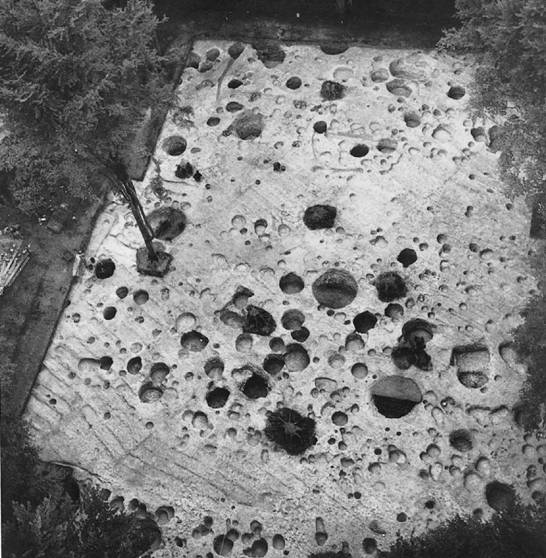

All these problems were overcome by a new method which appears to have been widely adopted in the south and east some time in the fourth century or soon after. Ditches were dug deeper and the rampart face was sheered back at an angle following the ditch side, thus creating a continuous slope from the bottom of the ditch to the crest of the rampart at an angle of 30–45°. At Hod Hill, Dorset, the overall distance from top to bottom was 17.4 m and at Danebury, Hants (Figure 15.5), 16.1 m, while at Maiden Castle, Dorset, it reached 25.2 m. Covered with a loose scree and capped by a breastwork of timber or flint, the approach would have been daunting to the attacker. The only maintenance problem was to keep the ditch clear of silt. This would have been undertaken periodically, the scree being thrown out on the downhill side creating a spoil bank sometimes referred to as a counterscarp. In one section at Danebury, it was possible to trace evidence of eleven different additions to the counterscarp, each representing a periodic clearing-out operation.

Glacis-style defences can be shown to replace timber structures at a number of sites from the Dorset forts of Poundbury, Maiden Castle and Hod Hill and the Somerset site of South Cadbury to as far north as Hunsbury in Northamptonshire and Breedon-on-the-Hill in Leicestershire, and it will be shown below (p. 359) that some early stone-built forts were also remodelled in this way. Dating evidence, where it survives, shows that glacis defences were in use in the south during the time when saucepan-style pots were being manufactured, centring therefore on the Middle Iron Age (fourth to second centuries); but at Croft Ambrey, Herefordshire, and Midsummer Hill, Worcestershire, in the Welsh borderland, dump-constructed ramparts were made at the beginning of the occupation sequence, which probably started in the fifth or even the sixth century. There is evidence from the south that here too dump ramparts without revetting were established by the eighth century. Such a rampart was found at Balksbury, Hants, in an eighth- to seventh-century context, at Quarley Hill and Woolbury, Hants, and Vespasian’s Camp, Wilts., dating to the fifth to fourth centuries, and at St Catharine’s Hill, Hants, a little later. On present evidence, therefore, it is simpler to assume that the technique of defending a site with a bank of spoil and a ditch was long established, dating back into the second millennium, and that after a brief period when timber- and stone-faced ramparts predominated, the older technique came back once more into common use and persisted in some areas until the Roman Conquest.

Figure 15.5 The defensive ditch at Danebury, Hants (photograph: David Leigh, Danebury Trust).

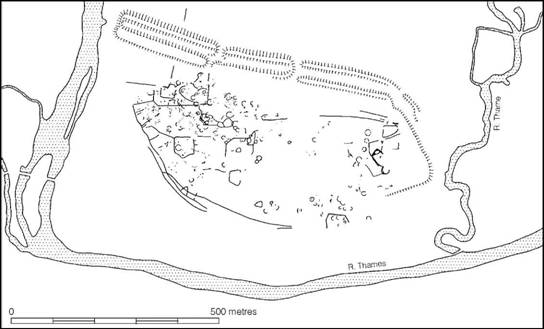

At Maiden Castle six subsequent extensions and modifications all adopted the basic glacis style, and at Hod Hill there were three phases. Evidently the glacis was regarded as the ultimate in defensive tactics until the wide flat-bottomed ditches of Fécamp style were introduced in the first century AD (p. 402).

Multivallation

Superficial surface examination of the British hillforts shows that many of them were provided with more than one rampart and ditch; such forts are listed on the Ordnance Survey Map of Southern Britain in the Iron Age as multivallate. The term is confusing, however, for it covers several different situations. The multiple-enclosure forts of the south-west, while strictly multi- vallate, were so because extra lines of banks and ditches were required to enclose space for livestock. Other forts like Wandlebury, Cambs., Danebury, Hants, Bredon Hill, Worcs., the Caburn, Sussex, and Croft Ambrey, Heref. and Worcs., give the appearance of multivallation because of their growth or shrinkage and not necessarily from a general policy of extending the line of fire. Thus, surface assessment alone can seldom be decisive. Nevertheless, deliberate multivallation for the purpose of defence can be demonstrated on sites like Maiden Castle, Dorset, beginning in phase III and reaching its ultimate development in phase IV (Figure 15.6). At Hod Hill, Dorset, it is possible to trace the development of multivallation, starting in stage IIa (the first glacis remodelling) with the construction of a palisade in front of the ditch. Subsequently a second ditch was begun but not finished, the spoil being thrown up over the line of the palisade, which was now isolated between the two ditches. Whether or not the palisade belongs to stage IIa, the fact remains that multivallation came late in the development of the fort and, as the excavator has suggested, may have been initiated and subsequently abandoned at the time of the Roman advance in AD 43.

A somewhat similar situation occurred at Buckland Rings, Hants, where, in spite of large-scale levelling, it was possible to trace a fence outside the line of the inner ditch and in front of an outer ditch. No evidence of a rampart behind or sealing the fence-posts survived. At what stage the outer features were constructed it is impossible to say, but in all probability they were added to the original construction, and it is possible that the Buckland Rings sequence is a direct parallel to Hod Hill. The occurrence, at Moel y Gaer, of a palisade of timbers set in a shallow bank outside the ditch, which may be contemporary with the rampart, is a reminder that outer palisades may well prove to be more widespread than has hitherto been appreciated.

Generally it may be assumed that multivallation was a late development in most areas, sometimes – as at Hod Hill – not appearing until the first century AD but probably at least a century earlier at Maiden Castle and South Cadbury. At Rainsborough Camp, Northants, it has been argued that the second rampart and ditch date to as early as the fifth century, but the evidence can be variously interpreted and is best regarded as unproven.

In all probability, development varied in different areas of the country and in different geographical situations. Two or three banks and ditches thrown across a neck of land to protect a promontory do not necessarily have to be related to the same time, or philosophy of display or warfare, as the multiple girding of Maiden Castle and South Cadbury. Thus, while most true multivallation was late, one may expect considerable variation between one part of the country and another. One final point is clear: there is now no need to suggest that intrusive ideas were the cause – local inventiveness is quite sufficient.

Figure 15.6 Maiden Castle, Dorset (photograph: Major G.W. Allen. Copyright, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford).

Chevaux-de-Frise

A few forts in Wales and northern Britain were provided with an additional form of barrier commonly known as chevaux-de-frise, a term used to describe zones of obstacles, usually stones, set upright in the ground to make access to the fort by men and horses more difficult. The stones vary in height, but average 0.60–1.0 m and were sited either in discrete areas, where the approach was easiest, or in continuous zones, in front of the defences. The most extensively excavated example is at Castell Henllys, Pembs., where a zone of upright stones was found well preserved beneath a later bank. The miniature nature of the barrier (the stones are barely 0.3 m high) and the careful choice of grey shale and white quartzite might suggest that the barrier was more symbolic and prestigious than functional.

In all, only five examples of chevaux-de-frise have been identified in Scotland and three in Wales (e.g. Mytum and Webster 1989), but it is possible, as Harbison has pointed out (1971), that many more may have existed in wood. No firm dating evidence exists, but the example at

Kaimes Hill, Midlothian, is unlikely to be far removed in date from the date of the second rampart, for which there is a radiocarbon assessment in the fifth or fourth century.

Stone and stone-and-timber defences in England and Wales(Figures 15.7 and 15.8)

Although palisaded structures were constructed in areas where good building stone occurs naturally, later developments in these regions usually adopted the technique of dry-stone walling, with or without internal timber binding. Unfortunately, horizontal timbers are far less easy to trace archaeologically than verticals, and it is therefore a distinct possibility that a higher proportion of the stone-faced ramparts were timber-laced than is at present apparent. Nevertheless, for the purpose of this discussion a distinction will be made between those where no timbering was observed and those known to have been timber-laced.

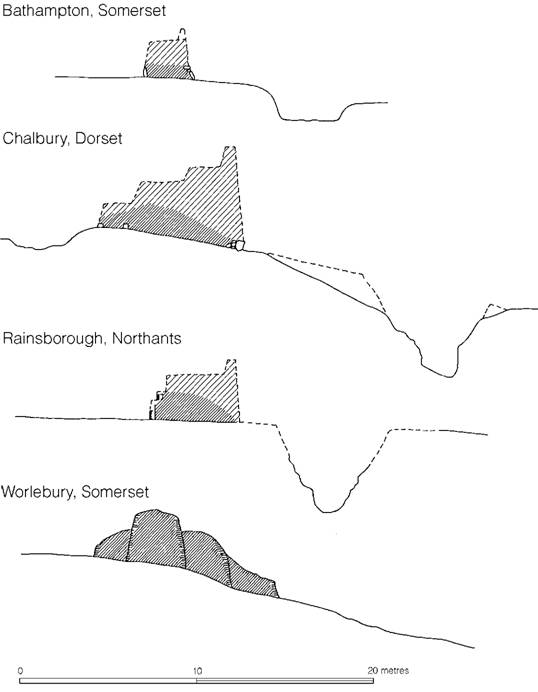

One of the earliest of the simple forts possessing a rubble rampart encased at the front and back with dry-stone walling is Chalbury, Dorset (Figure 15.7), where the total thickness of the rampart was 6 m. Since associated pottery leaves little doubt that the defences belong to the sixth to fifth centuries, Chalbury is presumably the stone-built equivalent of the timber-box rampart of Maiden Castle I, only 5 km away. An earlier date in the sixth century can now be proposed for the first fort at Rainsborough Camp, Northants (Figure 15.7), where the stone- faced rampart, 5.2 m wide at the base, was reduced in width by two steps at the back. The excavator’s suggestion that a similar stepping was adopted at the front carries less conviction. The thickness of the ramparts between the wall faces varies from fort to fort but is usually between 5.9 and 7.4 m. The enclosure at Bathampton Down, Somerset, was however protected by a wall only 2.9 m wide, divided by a 3.6 m berm from a wide flat-bottomed ditch. At Mam Tor, Derbyshire, the wall faces were 3.6 m apart, while at Worlebury, Somerset (Figure 15.7), the overall thickness of the main stone wall was 11.5 m; but this was apparently created by several additions or rebuildings at the back and front of a wall of normal width.

At several sites in the south, stone-structured ramparts were replaced by glacis-style defences. This is particularly well demonstrated at Llanmelin, Mon., and at Rainsborough Camp; in both cases, excavation has shown that the major remodelling in glacis style came late in the occupation of the site. One apparent exception to the rule is the much-quoted Bredon Hill, Worcs.; here the usual interpretation is that the inner rampart, built in a dump-constructed or glacis style, was followed by the outer rampart, stone-faced and fronted by a berm and U-shaped ditch. There are difficulties with this interpretation, not the least being that the two entrances through the outer rampart were almost blocked by the inner defences. If, however, the supposed constructional sequence is reversed, this problem would be overcome and the development of the rampart styles – first stone-faced then glacis – would be in accordance with the general pattern elsewhere, Bredon Hill being no longer the exception. The fact that the outer rampart and ditch were sited opposite the entrance in the inner rampart might be thought to provide further support for the reinterpretation.

Outside the south and east of Britain, the stone facing of the rampart seems to have survived to the time of the Roman invasion. In north-west Wales, Tre’r Ceiri, Garn Boduan, Carn Fadrun and Conway Mountain in Caernarvonshire all maintained their stone wall defences until the last, but the glacis style was adopted at some of the Welsh borderland sites like the Wrekin, Salop, and Croft Ambrey, Heref. and Worcs., and even penetrated as far north as Dinorben, Denbigh.

Figure 15.7 Stone-faced ramparts (sources: Bathampton, Wainwright 1967b; Chalbury, Whitley 1943; Rainsborough, Avery, Sutton and Banks 1967; Worlebury, Dymond 1902).

A combination of timbering and stone facing has been recorded on several southern British sites close to stone outcrops. In the outworks of the phase II east entrance at Maiden Castle, Dorset, dry-stone facing was employed instead of split timber or planks as a revetting material between vertical timbers erected in the general tradition of the timber-box rampart of the first period; and at South Cadbury, Somerset, exactly the same technique was employed. It should be emphasized that in both cases stone walling was being used only as a filling material in place of timber and not as an integral part of the rigid structure. This is essentially a local variation of the timber-box-constructed rampart, in areas where stone was readily available.

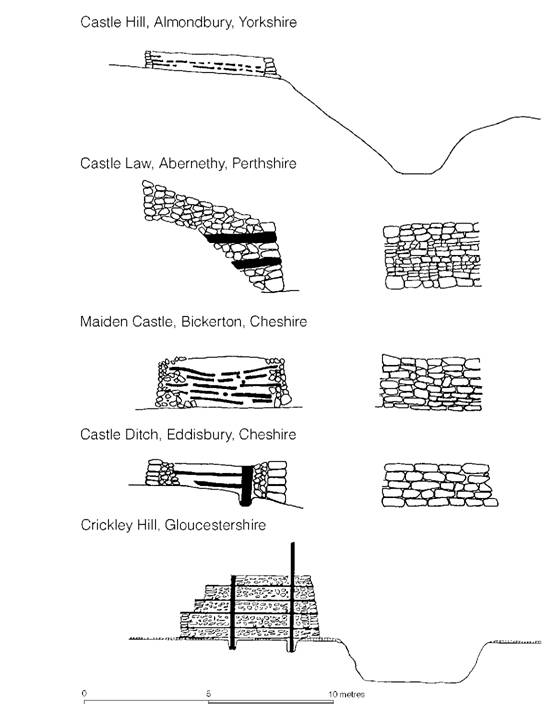

Further west and north, in an arc spreading from the Cotswolds through the Welsh borderland and Cheshire into Yorkshire, a series of partially excavated forts provide clear evidence of the use of timber and stone-structured ramparts. Some of the forts like Castle Ditch (Eddisbury), Cheshire (Figure 15.8), Dinorben, Moel y Gaer, Flints., and Ffridd Faldwyn, Montgomery, began as simple palisaded enclosures which were replaced by box-constructed timber ramparts employing vertical and horizontal timbering. Between the front verticals infilling was usually by dry-stone walling in the manner of South Cadbury and Maiden Castle. The same technique was used in the first and second phases of the rampart at Castle Hill (Almondbury), Yorks. (Figure 15.8). All, except for Dinorben, were later rebuilt using a rubble rampart laced with horizontal timbers, which in the case of Castle Ditches, Ffridd Faldwyn and Castle Hill was fronted, both inside and out, by dry- stone walling unbroken by timber verticals: the second phase of the rampart at Moel y Gaer does not however appear to have been stone-faced. The rebuilding of the Moel y Gaer rampart in this style post-dates a radiocarbon assessment of the fourth to third centuries.

Some of the forts in the west and north, such as Leckhampton Hill and Crickley Hill in Gloucestershire, Maiden Castle (Bickerton) in Cheshire (Figure 15.8), and Corley Camp in Warwickshire, began with horizontally timber-laced ramparts fronted by continuous dry-stone facings and many underwent subsequent modification.

The sequence at Crickley Hill, Glos., is particularly interesting. In the first defensive phase (the excavator’s period 2) the rampart appears to have been constructed in a composite form, with two rows of vertical timbers 2.1 m apart, giving rigidity to a rubble core which was laced with horizontal timbers and faced back and front with dry-stone walling, the timber ends projecting into the outer stone face. The overall width between the stone facing was 5.8 m. It is very tempting to interpret Crickley as a transitional type representing a stage between box-structured ramparts and timber-laced types. In theory all the builders have done here is to move the stone infilling of a conventional box-structured rampart outwards, away from the vertical timbers, perhaps to give more protection to the otherwise exposed woodwork. It would soon have been realized that the internal verticals were of little significance to the rigidity of the structure and could in future be omitted. This theory, while attractive, is difficult to substantiate. In a subsequent phase of rebuilding at Crickley (period 3b), when the wall was in part thickened and a hornwork constructed in front of the gate, only horizontal timbering appears to have been used (Figure 15.16).

From the above description, it will be seen that the use of stone and timber followed a series of complex patterns which are only now being gradually sorted out. Tentatively, however, we may define a phase in which stone was used as an infilling material in box-constructed ramparts of Ivinghoe Beacon and Hollingbury Camp type, spanning the period from the seventh to the fourth century. In the west and north of England, the technique of lacing the ramparts with horizontal timbers and facing them back and front with stone walls soon emerged locally, probably as a development from the earlier style. The dating evidence, such as it is, shows that the technique was being practised from the sixth to the third centuries. Eventually the use of horizontal timbers was abandoned and ramparts were built with stone facings only, in a simple style which probably originated earlier and continued in use in some parts throughout the Iron Age. Finally, in southern England and occasionally elsewhere, stone-constructed ramparts were eventually replaced by the glacis style. At present this generalized scheme fits all available evidence but regional and chronological differences may be expected to complicate the issue.

Figure 15.8 Sections and elevations of stone- and timber-laced ramparts (sources: various).

The stone and timber forts of Scotland

The Scottish hillfort development is in some respects different from that of the rest of Britain. Like the south, some forts began as palisaded enclosures, but after these had gone out of use, vertical timbering is virtually unknown again except in the gate at Cullykhan, where a date in the fifth century is indicated by a radiocarbon assessment. In the north the characteristic rampart structure consists of a rubble-and-earth core faced inside and out with dry-stone walling, the whole bonded by rows of horizontal timbers which project through the outer, and sometimes the inner, wall-face. At Abernethy, Perth, two rows of rectangular beam-holes 0.24–0.30 m square appeared through the outer wall-facing of the innermost rampart: the lower row was 0.60–0.90 m above the ground, the second row 0.60 m above the first. The outer rampart proved to be of the same construction, but in neither the inner nor the outer rampart did the timbers penetrate the inner wall-facing. It is impossible to say how extensive the use of longitudinal timbering was, since only at Abernethy are the timbers recorded. Ditches do not seem to have been an integral part of this kind of defensive scheme.

Half a dozen or so forts have produced direct evidence of timber-lacing but more than sixty of the Scottish sites belong to what is called the vitrified class, all examples showing signs of widespread burning of the timber-lacing causing the core material of the rampart to become discoloured and to fuse. The exact nature of the timber structure of most of these forts has not been recorded, but at Finavon and Monifieth in Angus, and Castle Law (Forgondenny), Perth – all forts timber-laced in the Abernethy style – vitrified material was found in the rampart cores. In all probability, therefore, we are dealing with a single class of horizontally timber-laced ramparts, some of which were fired. Whether the firing was deliberately carried out by the builders to consolidate the rampart, or by attackers, is a matter of some debate (summarized in Cotton 1955, 94–101, and MacKie 1976), but the potentially destructive nature of a fire, the unevenness of the firing within individual sites, and the relatively slight firing of many of them would suggest accident or attack rather than design. These vitrified forts should be compared with the burnt timber-laced ramparts of the west, e.g. Dinorben, Denbigh., Crickley Hill and Leckhampton Hill, Glos., and Bower Walls Camp, Somerset, where the limestone rubble cores have been turned to lime by the intensive heat.

There has been much discussion as to the date and origin of the Scottish forts (Cotton 1955) but most of it is now rendered obsolete by the advent of radiocarbon dating (MacKie 1969a). For charred beams or planks from behind the wall at Finavon a seventh-century date was obtained, with supporting dates spanning the sixth to third centuries for subsequent levels. At the vitrified fort of Dun Lagaidh, Wester Ross, a carbonized branch under the fort wall suggested a date in the sixth century but at Craigmarloch Wood in Renfrewshire a date of the first century AD was obtained, apparently for a timber-laced rampart which replaced a palisaded enclosure. The sample does not, however, seem to have been securely linked to the construction period and charcoal from beneath the wall provided a date in the eighth century. Finally at Craig Phadrig, Inverness, dates spanning the fifth to first centuries BC were obtained for charcoal associated with the vitrified rampart of the fort. Together the evidence is impressive: there can now be little doubt that many of the forts must originate in the seventh or even the eighth century, while the discovery of La Tène artefacts from some of the excavated examples, together with the Craig Phadrig dates, shows that occupation continued for several centuries during which time new forts were being built.

The Abernethy style forts originate, therefore, at the time when contacts between Scotland and the Hallstatt cultures of Europe were at their height. Similarities have been noted (Piggott 1966, 7) between the Scottish style of timber-lacing and the method employed on the Swiss site of Wittnauer Horn in both its Hallstatt B3 (Late Urnfield) and its Hallstatt C/D phases, and at Montlingerberg, another Late Urnfield fort in Switzerland. It is indeed tempting to suggest that the concept of using only horizontal timbers together with dry-stone walling was introduced into northern Britain from Continental Europe at the time of these maximum cultural contacts, but positive evidence is lacking.

Not all the Scottish forts were provided with timber-laced ramparts. Several of the fortified enclosures examined in the Cheviots, including Hownam Rings, Hayhope Knowe and Bon- chester Hill in Roxburghshire, were enclosed by simple stone-faced ramparts without internal timbering. At Kaimes Hill, Midlothian, the excavations have demonstrated the replacement of a timber-laced rampart with a simple stone-faced structure; radiocarbon dates for twigs from the rampart core suggest a fourth-century date for the change in style at this site.

Summary of hillfort defences

Controlled excavation, together with a substantial series of radiocarbon dates, is beginning to demonstrate a sequence for the development of defensive structures which is consistent over the whole country. The tradition of building defensive palisades appeared in most parts of Britain by the ninth century and continued to be employed probably into the seventh. In the south of Britain, including Wales, the use of palisades runs parallel with the construction of box-framed earth and timber ramparts of Ivinghoe type, which developed a backing rampart (Hollingbury and Moel y Gaer styles) by or soon after the sixth century. At present these types, incorporating vertical timbers, are unknown in the north. The seventh century saw the appearance in Scotland of the timber-laced rampart with external stone faces, a style of construction which was also adopted in western Britain as far south as the Bristol Avon. Which area, if any, can claim priority in the use of timber-lacing is uncertain. On one hand, it could be argued that the technique was introduced into Scotland from abroad, spreading to the south later, but an equally plausible explanation is that it was a British invention originating somewhere in the Cotswolds–Welsh border area out of the box rampart idea. At present this latter hypothesis seems the more reasonable, but the matter will only be solved when more closely dated examples become available.

By the fourth century timber-lacing had ceased to be practised, and over most of the stone-producing areas of northern and western Britain ramparts were constructed simply of stone-faced rubble. In the south, however, the vertical revetment of ramparts with close-spaced timbers persisted (Hod Hill and Poundbury types) probably throughout the fifth and even into the fourth century. During the fourth or third century old-established methods of building ramparts from dumped earth with a sloping face became widespread over much of the south and parts of the south-west. Eventually, by the first century AD, a new type of flat-bottomed ditch (Fécamp type) was introduced into the south-east, possibly from northern Gaul.

Entrances

Hillforts were provided with one or, less usually, two entrances. Since entrances were necessarily the weak links of the defensive circuit it is hardly surprising that much care and attention were lavished on these points, the entrances frequently being remodelled and rebuilt on more occasions than the main lines of the defences. A substantial number of entrances have been excavated on a reasonable scale. These, together with an examination of the earthworks of unexcavated examples, allow some general inferences to be drawn, and collated sequences can now be built up for the chalk downs of the south and the Welsh borderland.

In the south, two sites, Torberry in Sussex and Danebury in Hampshire, offer continuous sequences spanning the period from the fifth to the first century BC. These can be used in conjunction with the results from other excavations to produce a consistent picture of entrance development relevant for most of the south-east of the country.

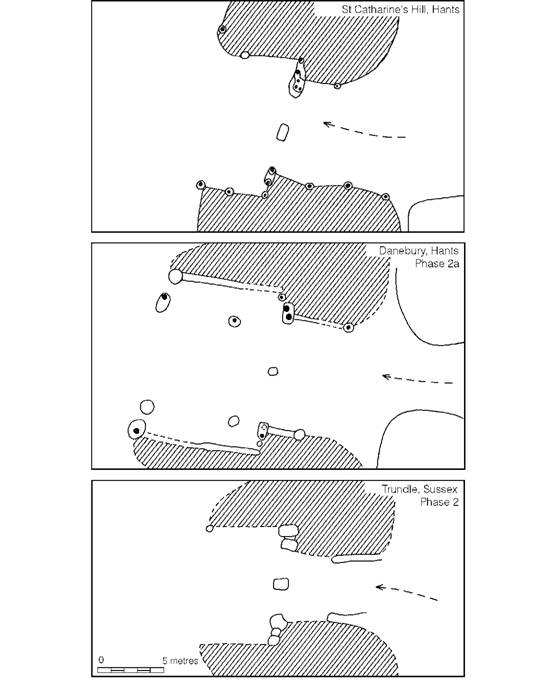

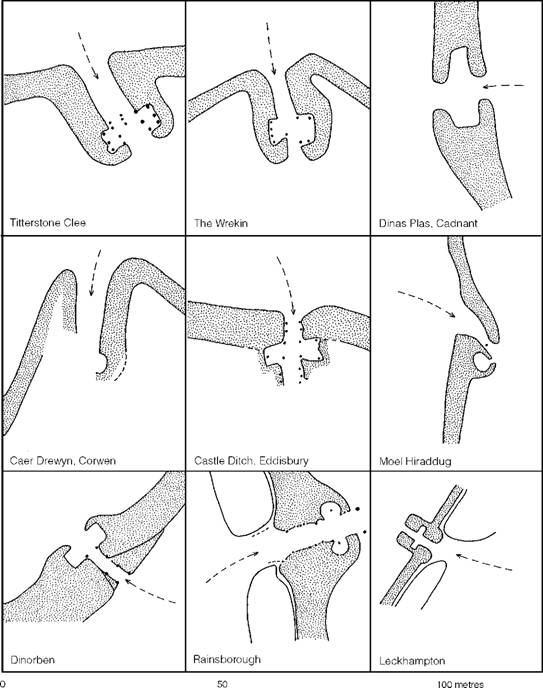

One of the earliest known gates, that belonging to the hillfort of Ivinghoe Beacon, Bucks., is a relatively simple structure consisting of a short timber-lined passageway 3.4 m long and of equivalent width, set back slightly at the end of a courtyard formed by turning the ends of the ditch inwards (Figure 15.9). The exact arrangement is not altogether clear but in all probability the rampart abutted on the timbers flanking the passage, although the possibility of additional side passages cannot be ruled out. An even simpler timber structure was provided at the east gate of Hollingbury Camp, Sussex (Figure 15.9). Two vertical timbers 3.7 m apart were set at the inner side of a gap in the box-constructed rampart; on them the gates would have been hung. This arrangement is exactly comparable to the first gate of Danebury, which probably dates to the sixth to fifth centuries (Figure 15.9).

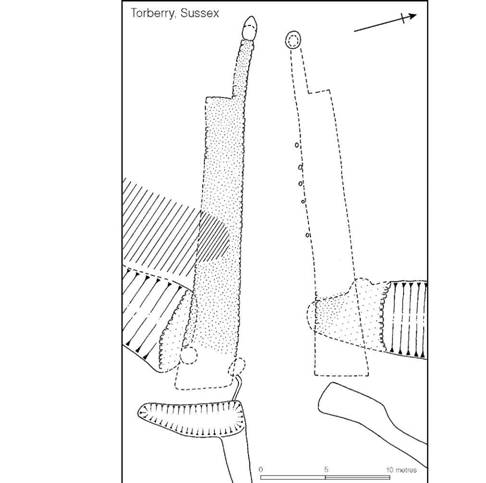

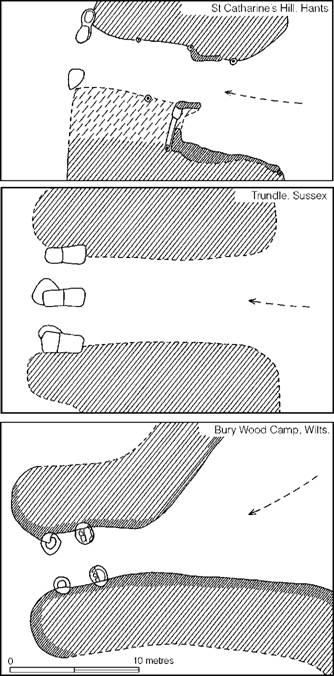

The second phase at Danebury represents the development of a more complex gate (Figure 15.10), embodying the idea of the dual-portal carriageway, which was maintained in use throughout several phases of rebuilding. Gates of almost exactly similar plan were in use in the first phases of St Catharine’s Hill, Hants, and at the Trundle, Sussex. A simpler form of the same basic concept, but with only a single passageway, was found in the first period at Torberry in the rampart which cut off the neck of the promontory defining the original defended area. The entrance, which lay on the north side of the ridge below the crest, consisted of a simple gap in the rampart, the ends being revetted with a continuous palisade of posts, with the large post- holes for the gate set a little in front, about 1.5 m apart. The ditch-ends were askew to each other so that the approach would have to be oblique. From the gate-posts shallow palisade trenches ran forward to the ditch-ends. This same type of arrangement can be traced, with modifications, at Quarley Hill, Hants, and at Yarnbury, Wilts. The main feature of both the dual- and single-portal entrances is that the gates themselves were set halfway along the entrance passage on line with the rest of the ramparts. Dating is fairly consistent: on the basis of sequence and associated pottery they should fall within the fifth century, possibly lasting into the fourth.

In the second period at Torberry the earthwork was carried around the summit of the hill, enclosing about 2.2 ha. The first entrance continued to be used at this time but in the third period the cross-defence and entrance were abandoned and partly dismantled, while the fort was extended eastwards, continuing the contour works of the second period along the sides of the ridge and enclosing a further 1.2 ha. The entrance through the new circuit lay on the axis of the ridge. In its original form the ditch-ends were placed askew to each other to form an oblique approach, but other details were obscured except for a row of posts which would have revetted one of the rampart-ends, creating a passageway 15–18 m long. The exact siting of the gate at this stage has been lost. The intention of the new entrance is, however, clear enough: the creation of a defended corridor extending into the fort between the rampart ends.

Figure 15.9 Single-portal entrances (sources: Hollingbury Camp, E.C. Curwen 1932; Danebury, Cunliffe 1972a; Ivinghoe Beacon, Cotton and Frere 1968).

Figure 15.10 Dual-portal entrances (sources: St Catharine’s Hill, Hawkes, Myres and Stevens 1930; Danebury, Cunliffe 1972a; Trundle, E.C. Curwen 1931 (author’s interpretation)).

The same appears to be true of other entrances. At Danebury, the third-period entrance was provided with a simple dual gate set back at the end of a revetted corridor 13 m long, while at the Trundle the gate of the second phase lay at the end of a corridor 15 m long. Much the same arrangement seems to have been constructed at the inner entrance at Yarnbury and at Blew- burton Hill, Oxon. Little dating evidence is available but in terms of the individual sequences a fourth-century date is probable.

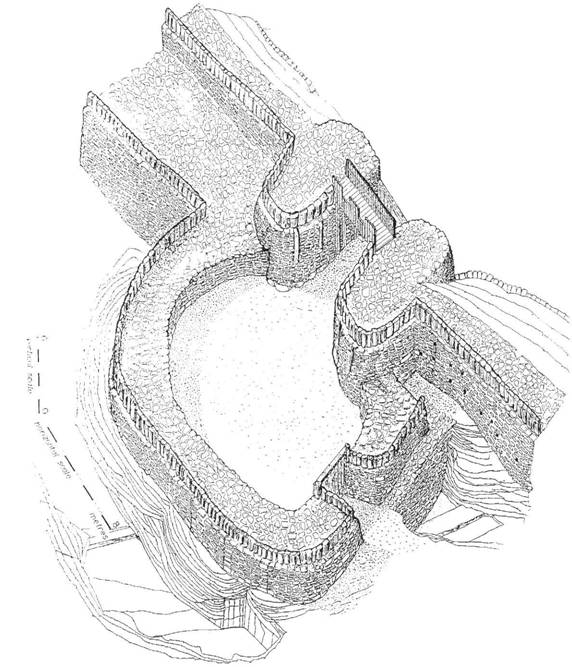

In the final stage at Torberry (phase IV) the entrance was remodelled on a massive scale (Figure 15.11): the ditch-ends were walled across and filled in, and the corridor was flanked on either side by substantial dry-stone walls 3.0–3.6 m wide extending into the camp for 27 m. At the inner end of the gradually narrowing passage lay the gate, represented by two post-pits. Both phases III and IV were associated with saucepan pots, showing that the creation of the corridor entrances lay within the Middle Iron Age. Much the same development was found at Danebury (Figure 6.7), where in the fifth period a long corridor approach to the gate was created by turning the ends of the rampart outwards to form a passage 45 m long, and building around them, as protection, a pair of claw-like hornworks containing an outer gate (Figure 15.13). From a platform created on the crest of the out-turned rampart it was possible for the defenders to control both gates and the entire compass of the entrance earthworks, as well as the approach to the fort.

Corridor entrances were common throughout the hillfort areas of southern Britain (Figure 15.12). At the neighbouring sites of the Trundle and St Catharine’s Hill, long in-turned corridors were now created out of the earlier gate structures, while at Bury Wood Camp, Wilts., the northeast entrance seems to have been first built in this style. Normally the corridor was constructed by turning the ends of the rampart into the camp as at Torberry, but in some cases, for example Buckland Rings, Hants, the Caburn, Sussex, and Llanmelin, Mon., partial or full multivallation contributed to the length of the defended approach, while at other sites like Danebury the corridor effect was created by out-turning the earthworks and protecting them with outer horn- works. A prime example of such an arrangement is the east entrance of Maiden Castle, Dorset (Figures 15.6 and 15.13), in phases II and III. Here any would-be attacker would have been confronted by a long tortuous corridor approach of more than 73 m, winding in and out between earthworks which shielded strategically placed artillery platforms designed, no doubt, to be manned by defenders with slings.

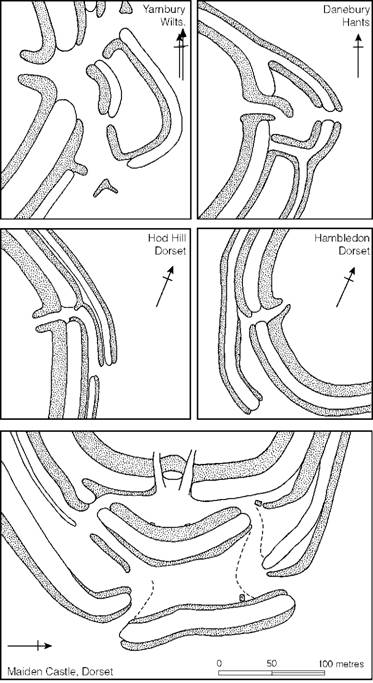

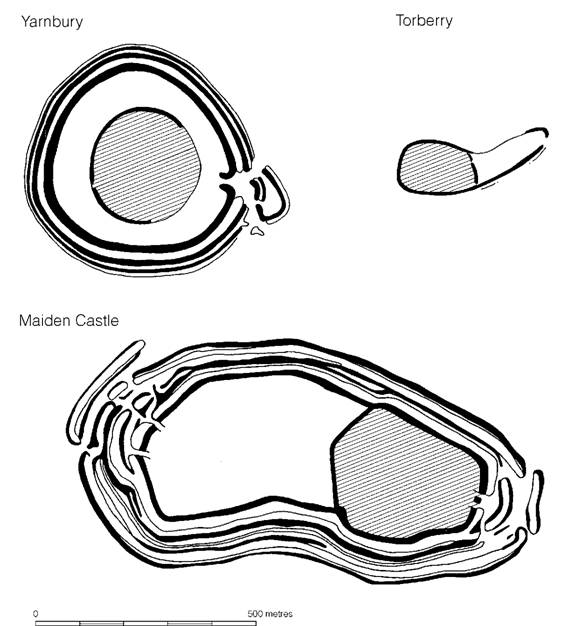

A somewhat simpler method, with the same overall advantages, entailed the construction of a single flanking earthwork attached to one side of the entrance and running parallel to it (Figure 15.13). This type can be most clearly seen at the Steepleton Gate of Hod Hill, Dorset, where a hornwork, unfinished presumably because of Roman attack, was added in front of an already in- turned gate, creating a corridor of 90 m overall length. The same technique was employed at the neighbouring Hambledon Hill and, in a modified form, at Rawlsbury and Badbury Castle, all in Dorset; the outworks of Yarnbury, Wilts. (Figures 15.13 and 15.14), in their latest form would have created a similar general effect.

Wherever dating evidence is available, simple in-turned corridor entrances of the Torberry type seem to date to the end of the Middle Iron Age, and even the more complex earthworks of Danebury belong to the same period, but the addition of flanking outworks is generally a later development, quite possibly not appearing in the south-west until the first century AD. Flanking works designed to deflect frontal attack are a far more sophisticated reaction to defence than the building of long corridors. It remains to be seen whether it was threat of Roman attack in AD 43 or earlier intertribal fighting which sparked off the development.

Figure 15.11 The last phase of the main entrance of Torberry, Sussex (source: Cunliffe 1976a).

Turning now to the sequence in the Welsh borderland hillforts, the work at Croft Ambrey, Midsummer Hill and Credenhill Camp in Herefordshire and Ffridd Faldwyn, Montgomery, when collated allows the main development trends to be isolated (Stanford 1971b). The earliest gate is a simple single-portal type found at Ffridd Faldwyn in association with a box rampart and tentatively dated to the eighth and seventh centuries. This was replaced by a series of twin-portal gates spanning the sixth to fourth centuries. Croft Ambrey, where occupation began towards the end of the sixth century, was also provided with a succession of twin-portal gates of broadly similar type.

It was probably during the fifth century or earlier that timber ‘guardrooms’ came into common use, appearing at Midsummer Hill and probably Credenhill Camp, but soon to be replaced by stone-built ‘guard-chambers’ of a kind which were also added to the Croft Ambrey gate for which a radiocarbon date of the sixth to fifth century has been obtained. Guard-chambers, or more correctly recesses, are well represented among the hillforts built in the stone areas of north Wales and the Welsh Marches, and extend south into Northamptonshire (Figure 15.15). Strictly, two different types can be recognized: chambers added immediately behind the ramparts – as at Rainsborough, Northants, Castle Ditch (Eddisbury), Cheshire, Leckhampton Hill, Glos., Moel Hiraddug and Dinorben, Denbigh. – and those built at the ends of long corridor entrances like Titterstone Clee and the Wrekin, Salop, and Pen y Corddyn Mawr, Denbigh. No positive evidence is yet available to suggest whether or not there is a chronological difference between the two types. If we accept the sixth- or fifth-century dating suggested by the single radiocarbon date for the appearance of chambers at Croft Ambrey, which gains support from the two radiocarbon dates now available from Rainsborough, and if the long corridor type of entrance plan was adopted in this area in parallel with its fourth- to third-century appearance in the south, then chambers must have been in use for several centuries. The problem is one which may eventually be solved by further excavation and radiocarbon dating. The possibility that the chambers may, in some regions, have been constructed at the same time is suggested by the very close similarities of those at the south-east gate of Dinorben and the main entrance of Moel Hiraddug (Guilbert 1979b). What function these chambers served, whether for defence or not, it is impossible to say.

Figure 15.12 Inturned entrances (sources: St Catharine’s Hill, Hawkes, Myres and Stevens 1930 (authors’ interpretation); Trundle, E.C. Curwen 1931; Bury Wood Camp, King 1967).

Figure 15.13 Comparative plans of complex outworks protecting hillfort entrances (sources: Yarnbury, M.E. Cunnington 1933; Hod Hill and Hambledon Hill, Richmond 1968; Maiden Castle, Wheeler 1943; Danebury, Cunliffe 1972a).

Figure 15.14 Yarnbury, Wilts. (photograph: Dr J.K.S. St Joseph. Crown Copyright reserved).

One characteristic of the corridor entrances of the south, which recurs in the Welsh border sites, is the construction of a bridge over the gate linking one side of the entrance passage with the other, providing obvious defensive advantages (Figure 15.16). In the south bridges are found with long corridor entrances dating to the third and second centuries. In the west similar features appear, also at a late stage in the local sequence – for example at Midsummer Hill and Croft Ambrey – associated at the former site with a radiocarbon date of the first century BC or early first century AD. The consistency in dating is impressive.

Figure 15.15 Comparative plans of hillfort entrance ‘guard-chambers’ (source: Gardner and Savory 1964 with amendments and additions).

In summary, it may be said that in the two areas where hillforts have been studied in some detail, a well-defined parallel development can be recognized, although there are some apparent differences in dating in the early stages. Divergence in structural detail begins in the sixth or fifth century with the development of guard-chambers in the western group, while at the southern sites the gates tend to be set further and further back. Some time during the Middle Iron Age, many of the gates in the south were remodelled as long corridor types in which the gates, combined with bridges, were constructed at the inner ends of corridors sometimes as much as 45 m long. At about this time bridges appear in the western group, possibly together with the limited adoption of the corridor type of entrance plan. It was probably during the first century BC or early first century AD that several forts in the south were provided with complex outworks, perhaps as a defence against threat of Roman attack, but outworks are not a common characteristic of the forts of the western group.

When more radiocarbon dates become available, particularly from forts in the south, greater refinements will be possible, and with further excavation regional variations will no doubt appear. Nevertheless, the general similarity of development over a large area tends to suggest a degree of parallelism, reflected also in basic hillfort structure, which can best be explained by supposing a community of common culture and persistent contact over a considerable period of time.

Regional differences in the planning and siting of hillforts

In the same way that the vernacular architecture of medieval Britain differs from region to region, so too it is possible to recognize peculiarities in the planning and siting of hillforts (Forde-Johnston 1976). The problem cannot be discussed in any detail here but attention must be drawn to the larger and more generalized groupings.

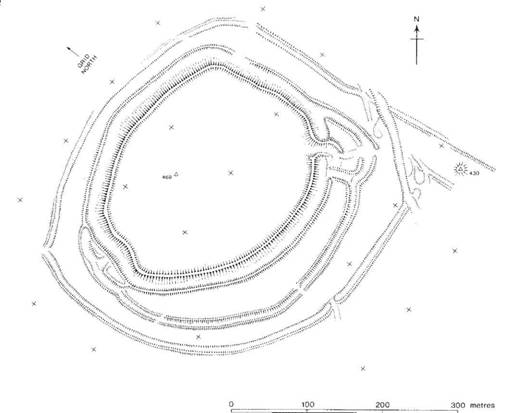

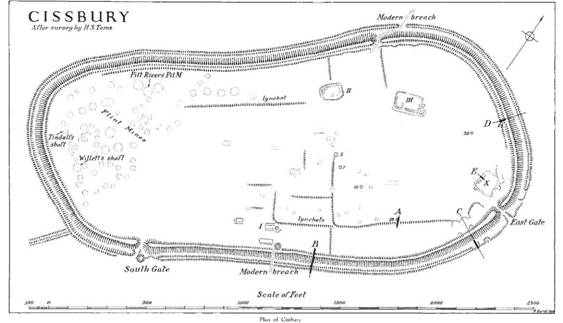

The normal hillfort of southern Britain – the so-called contour type – is in its initial stages usually a univallate structure with a rampart enclosing the crest of a hill (Figures 15.18 and 15.19). With exceptions like Cissbury and the Trundle in Sussex and St Catharine’s Hill, Hants, where the original circuits were not subsequently enlarged, many were increased in size. At some, like Yarnbury, Wilts., the early fort was completely replaced by an entirely new rampart roughly concentric with the first (Figures 15.14 and 15.20), while others were enlarged with a single addition as in the case of Maiden Castle, Dorset, and Torberry, Sussex (Figure 15.20), or more than one addition like Hambledon Hill, Dorset (Figure 15.21). Multivallation, where it occurs, can usually be shown to be late.

Contour forts are to a large extent the natural result of fortifying a gentle downland landscape, but even within the area of the chalk downs there are steeper ridges and promontories demanding different treatment. Torberry is a good example of this: here, in its first period (Figure 15.20), a cross-defence was constructed across the ridge, cutting off and protecting the end of a promontory; only later was the fort converted into a conventional contour work.

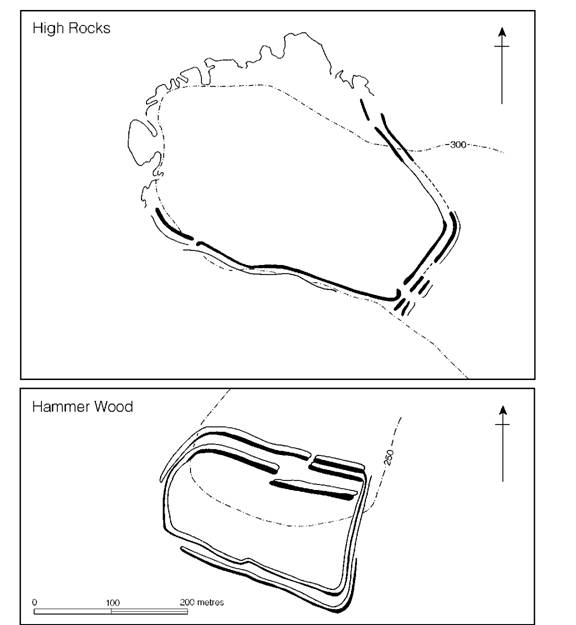

In the Weald, where much of the countryside is more sharply dissected by streams, promontories were usually chosen for the siting of forts. In the case of High Rocks and Hammer Wood (Iping) in Sussex (Figure 15.22), multiple defences were constructed across the neck of the ridge with much slighter earthworks around the other slopes where the land falls steeply away. The Wealden forts were simply making the optimum use of the defensive possibilities of the landscape.

Figure 15.16 Reconstruction of the gate of Crickley Hill hillfort, Glos. in its final stage, period 3b (reproduced from Dixon 1994, ill. 186).

Figure 15.17 Distribution of two distinctive hillfort entrance types (source: author).

The same general principles can surely be applied to the cliff castles of Cornwall and southwest Wales (Figures 13.12 and 13.17). Headlands projecting into the sea needed only short lengths of artificial defences cut across the neck to render them virtually impregnable. Admittedly, the structural similarities of the Cornish cliff castles as well as certain aspects of the material culture show strong links with the Armorican peninsula – an area of similar geo- morphological structure. But the absence of cliff castles in Cornwall would have been more culturally significant than their presence, for the structure of the countryside demands this type of fortification.

While geomorphology is a significant factor in the siting and form of hillforts, geological considerations, particularly the availability of good building stone, can sometimes have a direct effect on actual structure and perhaps on form. In the Cotswolds it is possible to trace a group of relatively small univallate forts of almost circular plan – including Lyneham, Ilbury, Idbury Camp and Chastleton in Oxfordshire and Windrush Camp, Glos. – which contrast with the vast enclosures of more than 22 ha, usually sited on ridges, like Norbury Camp (Northleach) and Nottingham Hill, Glos. (Rivet 1961, 33). Exactly what factors were involved in the evolution of these two classes is not clear but economic and social considerations may well have been important, while the circular form of the smaller category may have been encouraged by the availability of building stone.

Economic factors were of considerable significance in influencing fort type. It has already been emphasized (chapter 13) that the multiple-enclosure forts of the south-west peninsula and southwest Wales were a response to the predominantly pastoral economy of these regions, but it would be more accurate to regard them as fortified homesteads. The adding of annexes to the large forts, however (a response to comparable economic pressures), gives several of the forts in the Welsh borderland an overall similarity to them, but a similarity brought about by the demands of the farming economy rather than by culture, chronology or geology.

Figure 15.18 Danebury, Hants (source: Cunliffe 1972a with amendments).

To some extent, isolation can give rise to regional variations (Figure 15.17). The hillforts of Caernarvonshire (Hogg 1962) demonstrate this particularly well. Their large size, hill-top siting, simple dry-stone walled structure and dense internal occupation serve to unite the group and to distinguish them from the structures in the north-east of the Principality, which relate more closely to those in the Welsh borderland. An even more impressive demonstration of regionaliza- tion is provided by a consideration of forts in Scotland (Feachem 1966), where by ground survey alone several distinctive types of plan, clustering significantly together, have been recognized.

This brief survey may have erred too much on the side of geographical determinism, but in the past too much emphasis has been placed on cultural/historical explanations when discussing hillfort form. Regional isolation, geology, geomorphology, economy and social structure are of far greater significance in determining siting and planning. In those areas between which cultural contacts were strong, a degree of uniformity and parallel development prevailed. Where, however, areas of countryside were isolated by natural features, a greater regionalization is apparent.

Figure 15.19 Cissbury, Sussex (source: reproduced from Curwen and Williamson 1931).

The development of hillforts

Wessex and adjacent areas

Leaving aside considerations of chronology, the distribution of hillforts in Britain is far from even. As Figure 15.1 so clearly shows, there is a marked concentration in a zone beginning in Wessex and the South Downs and continuing through the Cotswolds and the Welsh borderland to the coast of north Wales. It is within this central southern zone that the majority of the hillfort excavations have been carried out and all the large-scale excavations of recent years have been focused. Thus the database for the region, though leaving much to be desired, is far better than for any other part of Britain or parts of the adjacent Continent. Sufficient is now known to allow a general development model to be put forward (Cunliffe 1984c). For ease of discussion the simple chronological framework outlined in chapter 5 will be adopted: earliest refers to the period from c. 800 to 600, early to 600–c. 400/300 and middle to the period from 400/300 to 100 BC.

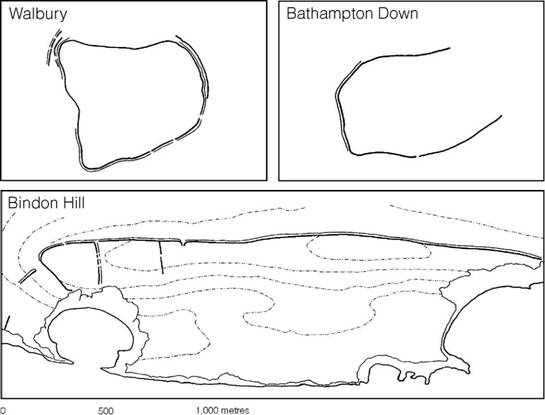

The earliest hillforts (Figures 15.23 and 15.24)

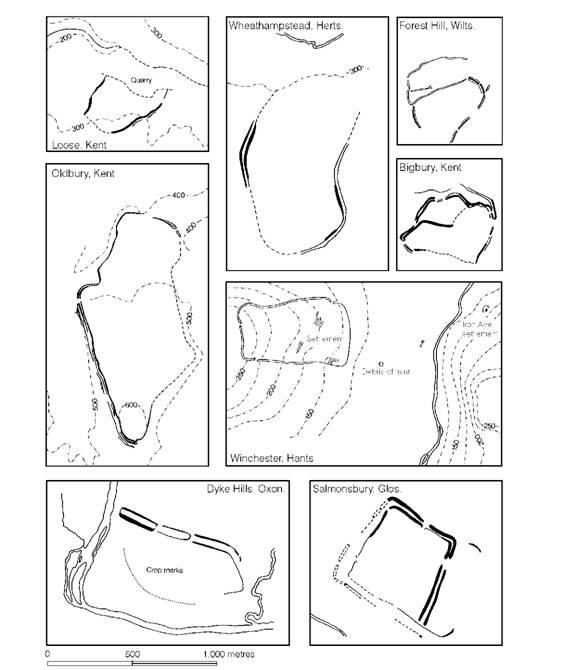

Hillforts of the earliest period fall into two distinct categories: vast straggling structures with slight defences usually over 10 ha in extent; and small strongly defended enclosures usually multivallate and occupying ridge-ends.

The larger group are better referred to as hill-top enclosures since their enclosing earthworks are hardly of defensive quality. Size varies from the small enclosure of Winklebury I (6.8 ha) to gigantic sites like Ogbury, Wilts. (25 ha), Norbury, Glos. (32 ha), Bathampton Down, Avon (32.5 ha), and Walbury, Berks. (35.2 ha); Bindon Hill, Dorset, is considerably larger if all the land to the present sea coast is included. Altogether there are ten to fifteen sites of this kind centring on Wessex but stretching from Sussex to Gloucestershire (Wainwright 1967b). Others can be identified further afield at Nadbury Camp and Borough Hill, both in Northamptonshire, and at Ivinghoe Beacon, Herts. The interiors of four have been sampled on a reasonable scale: Harting Beacon, Sussex, Balksbury, Hants, Winklebury I, Hants, and Norbury, Glos. All share similar characteristics: the defences were comparatively slight, there was a dearth of occupation debris and internal structures were sparse. In Harting Beacon and Norbury only a few small four-post structures were discovered, but at the more extensive excavations of Balksbury and Winklebury a few contemporary circular structures, possibly houses or shelters, were found. The enclosure at Hog Cliff Hill, Dorset, belongs to this same general category. Here, following a Late Bronze Age settlement, a slight ditched enclosure of some 5.6 ha was constructed within which were a series of circular buildings. The enclosure was subsequently enlarged to 10.5 ha and the buildings were replaced by penannular mounds of flints built apparently as shelters.

Figure 15.20 Hillforts which have been extended. The shaded areas represent the initial enclosures (source: Cunliffe 1984c).

Figure 15.21 Hambledon Hill, Dorset. Successive extensions can be discerned (photograph: Dr J.K.S. St Joseph. Crown Copyright reserved).

While the function of these early hill-top enclosures is obscure, the lack of evidence for intensive occupation is consistent and points to the possibility that they may have been used only sporadically, but the replacement of circular structures at Winklebury I is sufficient to show thatoccupation was more than a single brief event. The four-post structures, which characterize the internal occupation, are conventionally called ‘granaries’. This however is an observer-imposed terminology and such simple post settings could equally well have served as racks or platforms for any kind of storage. While no firm conclusion can yet be offered as to the function of these enclosures, one possibility is that they represented communally built structures related to a seasonal activity within the farming year. If the small four-post structures are interpreted as hay racks or fodder stores of some kind, then the enclosures could well have served for autumn corralling. Flocks and herds would need to be rounded up for sorting, castrating and culling and this is most likely to have been a communal activity. Evidence for this comes from Balksbury, where a careful examination of the soil accumulation behind the rampart demonstrated intensive use of the site by cattle. It is possible that over-wintering of stock may also have been focused on enclosures of this kind, in which case some accommodation for the guardians of the livestock would have been necessary. These are, of course, only hypotheses, but some such use would fit well with our general concepts of socio-economic development which will be considered in more detail below (chapter 16).

Figure 15.22 Wealden promontory forts (sources: High Rocks, Money 1968; Hammer Wood, Boyden 1957).

Figure 15.23 Early hill-top enclosures (source: author).

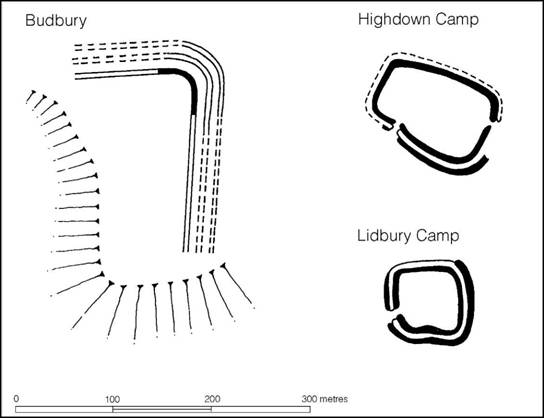

The second category of ‘hillfort’ in the earliest phase of the Iron Age can be characterized as small enclosures of 1–3 ha in extent, strongly defended often with multiple earthworks, the interior producing rich occupation deposits (Figure 15.24). Sites of this kind are not particularly well known, but at Budbury, Avon, excavation has defined a 3 ha enclosure with a complex of ramparts and ditches occupying the end of a steep promontory. Limited excavation within the interior produced a considerable range of debris pointing to intensive occupation. Lidbury Camp, Wilts., is also of this period. Here a small strongly defended rectangular enclosure produced eleven storage pits in a comparatively limited area excavation. Oliver’s Camp, Wilts., and Highdown, Sussex, are among others that have been examined on a sufficient scale to show that they belong to the same general category. It is tempting to see these defended settlements as the permanent bases of a sector of society, perhaps an aristocracy if the defences are thought to reflect status. Once more, however, the excavated data are too sparse to allow firm conclusions to be drawn.

Figure 15.24 Defended ridge-end forts (source: Cunliffe 1984c).

Hill-top enclosures and defended settlements are two features of the contemporary settlement pattern of Wessex. Others include the large and apparently open settlements typified by All Cannings Cross and Potterne, Wilts., while the ditch-enclosed farmstead of Old Down Farm, Hants, represents another type. Our so-called earliest ‘hillforts’ must then be seen as only one element in a varied pattern representing a complex social hierarchy.

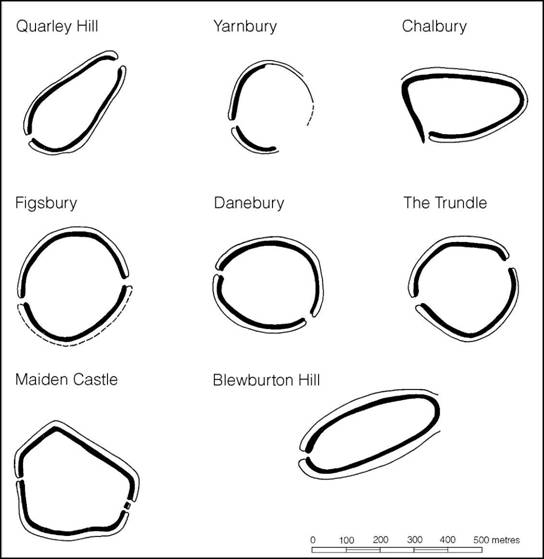

Early hillforts(Figures 15.25 and 15.26)

The Early Iron Age in central southern Britain, which covers the period roughly of the sixth and fifth centuries, was a time of developing cultural uniformity. Though distinctive regional pottery styles serve to distinguish what might be regarded as emerging ethnic entities, throughout the broadest region a new type of early hillfort appeared. These were usually contour works, averaging 5 ha in extent. They were defended by a single ditch, backed by a rampart usually faced inside and out with stonework or timber or a combination of the two. There were normally two entrances on opposite sides of the enclosure (Figure 15.25). From what is known of their distribution in Wessex, forts of this kind would seem to have been densely and quite evenly scattered across the landscape, and many of the typologically later hillforts may, on excavation, prove to have originated in this period (Cunliffe 1984c, 19–23). Few, if any, developed from fortified enclosures of the earliest period but at Danebury there is some evidence to suggest that the early hillfort was constructed within a larger and slighter enclosure which contained four-post structures. This may prove to be a more widespread phenomenon than was originally appreciated but such relationships are impossible to discern from surface characteristics alone.

The area of downland between the rivers Test and Bourne has been thoroughly investigated and can provide a fair indication of the density of early hillforts in the landscape (Figure 15.27). In all, five hillforts are known. Of these, one, Balksbury, originated as an early hill-top enclosure but was not fortified or occupied in the early period. The other four, Bury Hill, Figsbury, Danebury and Quarley, with Woolbury to the east of the Test, all provide some evidence to suggest that they were built and used within the early period. These sites were closely located between 8 and 11 km apart but there is no reason to suppose that this density was unusual for Wessex in the early period.

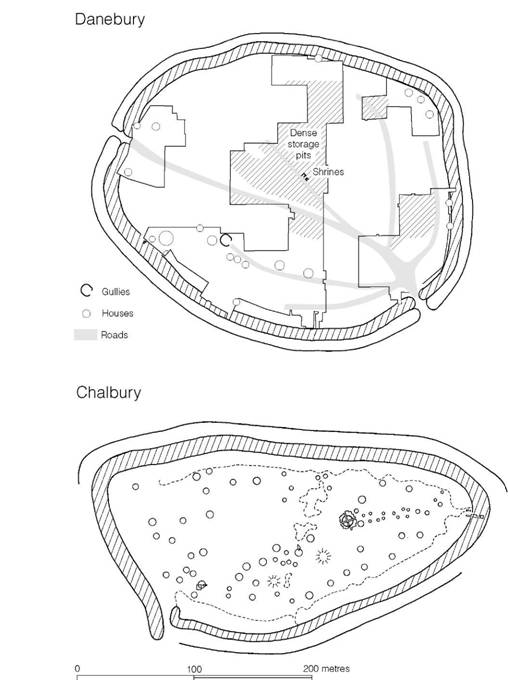

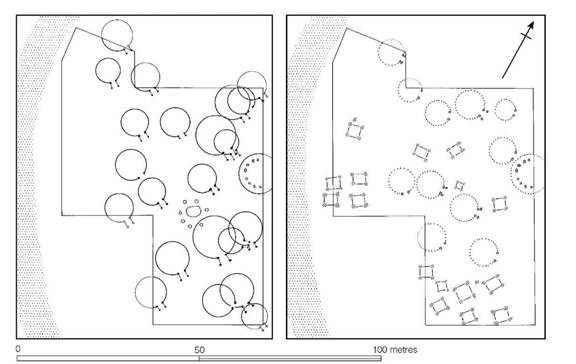

Four early hillforts have been the subject of programmes of area excavation, but on varying scales: South Cadbury, Somerset, Chalbury and Maiden Castle, Dorset, and Danebury, Hampshire (Figure 15.26). Only at Chalbury was the site found to be uncluttered with later occupation. Here surface evidence of thirty or so large circular depressions was recognizable and the three of these that were excavated proved to be houses. The many smaller depressions probably represented pits, only one of which was uncovered. The surface features suggest that some zoning may have existed, but without intensive excavation it is impossible to say. A rather clearer picture emerges from the large-scale area excavation at Danebury where, in spite of much later occupation, the early plan can be clearly discerned. Much of the central area, around two buildings which may have served as shrines, was used solely for the siting of pits, probably for grain storage, while in the peripheral zone behind the ramparts, wider on the south than the north, circular houses, storage pits and post-structures concentrated: it was here that occupation debris was at its densest. The more limited evidence from Maiden Castle and South Cadbury suggests that all four sites were broadly comparable in this early period.

Early hillforts differ noticeably from early hill-top enclosures in that they were smaller and better defended, and internal occupation was dense and probably continuous, the debris showing that a wide range of normal domestic activities were undertaken. The enclosing earthworks were clearly regarded as defensive. Their siting was carefully chosen to make the most of the natural contours and the gates were strongly fortified. At Danebury and Maiden Castle forward projecting hornworks were added during the early period. There is also ample evidence at both sites and elsewhere, e.g. Figsbury, South Cadbury, Chalbury, Quarley, Woolbury and St Catharine’s Hill, that the defensive circuits were refurbished from time to time. Copious collections of slingstones from Danebury and Maiden Castle provide added evidence of defence, while traces of burning at Danebury and St Catharine’s Hill may have resulted from an attack. For all these reasons we may fairly regard these sites as fortifications designed to protect the community from raids. But within this group of early forts there is variation. In the Danebury region, for example, there is evidence to suggest that Quarley, Woolbury and Figsbury were built later than Danebury and Bury Hill by perhaps a century or so, and only Danebury shows any sign of intensive occupation (Cunliffe 2000, 163–6). The social implications which follow from this are best left for later discussion in chapter 21.

Figure 15.25 Comparative plans of early hillforts (source: Cunliffe 1984c).

Figure 15.26 The interiors of early hillforts (source: Cunliffe 1984c with modifications).

Figure 15.27 The hillforts of the Danebury region, showing their theoretical territories constructed on the basis of Thiessen polygons. The lower diagram indicates duration of occupation of the forts (source: Cunliffe 1976b with later modifications).

Middle Iron Age hillforts

In the period 400–300 BC a widespread change can be detected in Wessex: a number of the early hillforts were abandoned while those that remained in use were refortified, frequently on a massive scale: these we refer to as developed hillforts. Danebury provides a good example of what this entailed. Here the early rampart was greatly increased in volume with material largely derived from a wide quarry trench dug just behind the rampart tail. The ditch was also recut as a deep V, the inner side of which was continuous with the front slope of the rampart. One of the entrances was now blocked, while the remaining one underwent a series of changes culminating in a long corridor type protected by a complex of outworks.

A number of early forts, including South Cadbury and Blewburton, were modified in this way but elsewhere enclosed areas were increased. At Maiden Castle and Torberry the new defences, while following part of the earlier circuit, incorporated new areas, while at Yarnbury the old defences were entirely abandoned, the new enclosure taking a much wider circuit (Figure 15.20). Clearly within the general pattern of Middle Iron Age re-defence a range of strategies were adopted. Moreover, one has only to compare the three plans illustrated on Figure 15.20 to appreciate the considerable variation in size, and presumably therefore status, among the developed hillforts.

Although a majority of the developed hillforts emerged as modifications of functioning early forts there are a few possible examples of early hill-top enclosures being brought back into use after a century or two of abandonment. Winklebury (if accepted as an early hill-top enclosure) may be one such, and it is possible that Hod Hill, Dorset, is another though the available evidence is ambiguous. Sometimes virgin sites seem to have been chosen for developed hillforts. This would appear to be true of a number of the hillforts of Kent and Surrey where radiocarbon evidence suggests that occupation began in the fourth or third centuries (Cunliffe 1982b).

As a broad generalization it can be said that over most of central southern Britain there were many fewer developed hillforts than there were early hillforts. This is particularly clearly demonstrated in the Test–Bourne region (Figure 15.27), where of the four early forts occupying the territory in the early period only one, Danebury, continued as a developed hillfort in the Middle Iron Age. In other words Danebury became the single dominant focus in a landscape. A number of settlement sites in the countryside around were also abandoned at this time.

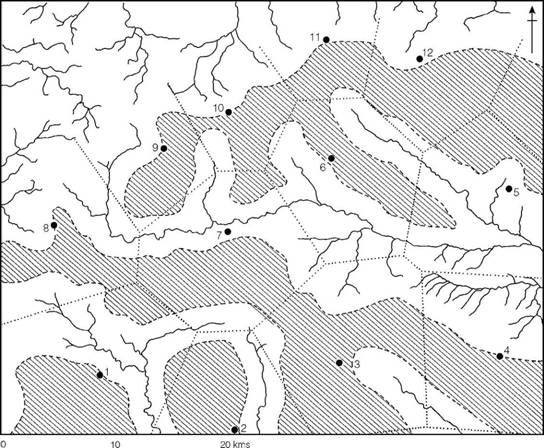

Reflections of a similar process can be discerned on the Sussex Downs, an elongated chalk ridge divided into distinct blocks by rivers. The total number of hillforts is quite large (Figure 15.28), but when the few forts producing evidence of Middle Iron Age occupation are plotted they can be seen to be spaced evenly, with each fort occupying a discrete block of downland, giving the impression of distinct territoriality (Bedwin 1978b; Hamilton and Manley 1997 and 2001).

Much the same pattern emerges on the downs of northern Hampshire and Berkshire (Figure 15.29). The twelve sites displaying characteristics of Middle Iron Age developed hillforts are evenly spaced within the landscape and all occupy similar positions in relation to the two principal resource potentials: the unwatered downland and land within easy reach of permanent water supply. These fortified locations have emerged from a complex of earlier fortifications to be the focal points of discrete territories, their survival, no doubt, aided by their favourable locations.

The date of the appearance of developed hillforts would seem to lie in the fourth or third century BC based partly upon a series of radiocarbon dates and partly upon an assessment of the associated ceramic assemblages. Even so, dating cannot be precise and while it is possible that the forts sprang into existence in their developed form at more or less the same time in the early fourth century BC, the possibility must be allowed that they emerged over a far more extended period.

Figure 15.28 Hillforts on the South Downs (source: author).