16

Food-producing strategies

The processes by which a community produces its basic food supply are conditioned by climate, soil and the technological capability of society at the time. All three are variable. Climate, as we have seen (pp. 33–4), can change even over comparatively short periods, soil can degenerate and lose its nutrients through overuse, while better tools or new varieties of cereal can be introduced at any time. There is a dynamic relationship between these three constraining factors. Together they control the food-producing strategy, but since the variables are constantly, if often only imperceptibly, changing, so the food-producing regime is never entirely static. Another factor adds to the variety. A country such as Britain, with an immensely varied geomorphology and microclimate, is a palimpsest of different bioclimatic regions. Each provides a framework within which society has to mould its systems. Thus, in attempting to study the way in which Iron Age communities raised their food we are dealing not with a single system but with many, each with its own trajectory of change.

The evidence at our disposal is of differing types and qualities. The analysis of pollen from peat deposits provides an invaluable yardstick. In the west and north the data are tolerably good (Turner 1981; Wilson 1983; Caseldine 1980; Caseldine and Maguire 1981; Dumayne-Peaty 1998) but from the chalklands of central southern Britain sequences are few (Waton 1982). Against this background the cereals themselves can be assessed. Palaeobotany has come a long way since Helbaek’s pioneering study of 1952 based entirely upon seed impressions found in pottery. Techniques of flotation, whereby carbonized grains are separated from soil, were not developed on any systematic scale until the late 1960s and then it was only Martin Jones’ seminal study of the plant remains from Ashville, Oxon., published in 1978, that showed how much could be gained from a thorough integrated study of a single site. The debate was further advanced by Gordon Hillman’s critical discussion of our techniques for reconstructing crop husbandry practices from charred remains (1981) in which he stressed the importance of studying, from surviving residues, the entire range of activities associated with crop processing. Since then it has been customary for all excavations to be sampled for plant remains and several regional overviews have been published, most notably by van der Veen (1992) and M. Jones (1995, 1996).

The study of animal bones has a longer pedigree, but even by as late as 1980 very few large assemblages had been published and those which had were usually simply treated. The work of Annie Grant (1984a) on the bone assemblages from Danebury, Hants, shows what can be gained from the thorough numerical study of a large and well-stratified assemblage. Not all soils, however, preserve bone, and there are large tracts of the country, where acid soil conditions prevail, from which no useful bone assemblages can be expected. Differential survival will always unbalance the picture.

A further source of useful data is provided by a study of insect remains from waterlogged situations. The species present are a ready indicator of local conditions and may also reflect on the activities being undertaken in the immediate environment. The impact which such a study could have on the understanding of an Iron Age settlement was demonstrated for the first time by Mark Robinson for the flood plain settlement at Farmoor in Oxfordshire (Lambrick and Robinson 1979). Finally, the study of terrestrial molluscs in ancient soils provides an invaluable tool in reconstructing the vegetational setting of sites and in showing how landscape use has changed with time (Evans 1972).

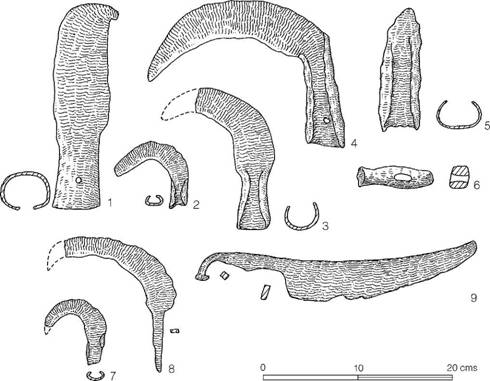

While the study of the faunal and floral remains themselves are central to an understanding of food-producing strategies, an assessment of the technical competence of the communities and the field monuments which they created has much to offer. Tools are well represented in the archaeological record by those iron parts which remain (Figure 16.1), and from these it is possible to deduce much of the general technological level at which society functioned (Rees 1979). In addition we have the physical marks of man on the landscape – the clearance cairns, lynchetted fields, ditched fields, linear boundaries, corrals, etc. – which resulted from society imposing its agricultural and stock management schemes on the land. Taken together the evidence is rich and varied.

In the pages to follow we will first consider the range and potential of the plants and animals so essential to society’s wellbeing, before proceeding to consider the evidence currently available for outlining regional strategies.

Plant cultivates and agrarian technology

Over most of the inhabited parts of south-east Britain, grain production formed the basis of the economy. Throughout the second millennium, emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum) and barley, in particular the naked variety (Hordeum tetrasticum), constituted the main crops though not to the exclusion of other varieties, but late in the second and early in the first millennium two changes became apparent: first, naked barley was replaced by the hulled variety (Hordeum hexa- sticum) so that by the middle of the first millennium the percentage of the naked type had been reduced to less than a third, and second, the popularity of emmer wheat began to give way to spelt (Triticum spelta). This change is part of a broader pattern of diversification which becomes noticeable at this time (Jones 1984, 121–2).

The implications of the change in staples can best be appreciated by considering the characteristics of the various cereals. Emmer, while growing well on most soils, is particularly well suited to light, comparatively dry soils like those of the chalk and limestone uplands, but since it is susceptible to frost it is not well adapted to winter sowing. Spelt, however, grows well on heavy soils and is a hardy variety able to withstand cold, wind and disease (Jones 1981, 106). Moreover it delivers a higher yield than emmer (van der Veen and Palmer 1997). Barley, on the other hand, whether naked or hulled, may be grown practically anywhere in Britain except in areas of poor drainage or high acidity (ibid., 105).

The growth in popularity in spelt could, then, be taken to imply the colonization of heavier soils. The spread of cultivation to a wider range of ecological niches is supported by the settlement evidence in the south-east of the country, which shows that farmsteads were now moving on to heavy clay soils, and by a study of weeds of cultivation associated with carbonized plant remains. From two Hampshire chalkland sites, Micheldever Wood and Danebury, seeds of the acid-loving weed Chrysanthemum segetum have been discovered, implying that, by the Middle Iron Age, the clay-with-flints capping to the chalk downs was being exploited. Weeds from damp locations, found at Danebury, show that crops were being brought into the site from nearby river flood plains. A similar study of the weeds of cultivation found with the crops at Ashville, Oxon., leaves little doubt but that all the easily exploitable soil in the region was being farmed. The introduction of spelt on a large scale would therefore have had considerable advantages, not least at a time of population pressure, in allowing new land to be brought under cultivation. The change-over from emmer to spelt during the Early Iron Age seems to have affected much of southern and central Britain and has been traced north as far as the Tees, beyond which point emmer remained the dominant wheat (van der Veen 1992).

Figure 16.1 Iron tools: 1 bill-hook from the Caburn, Sussex; 2, 3, 4, 7, 8 reaping hooks from Barbury Castle, Wilts.; 5 ploughshare from the Caburn, Sussex; 6 hammer from the Caburn, Sussex; 9 knife from Barbury Castle, Wilts. (sources: Barbury Castle, MacGregor and Simpson 1963; the Caburn, Curwen and Curwen 1927).

On the Hampshire chalkland a detailed study of crop remains from a number of sites has suggested that in the Early Iron Age spelt and six-row barley were probably sown together in the autumn as one crop or maslin (known as beremancorn in the medieval period) (G. Campbell 2000), but by the Middle Iron Age, while maslin continued to be autumn-sown, spring-sown barley crops were introduced. The advantages of introducing spring sowing were considerable. Not only could the workload be spread but so too could the risk of crop failure. Moreover the extended harvest would mean that fresh grain was becoming available over a period of time as stored supplies might have been running low.

Further diversification was introduced in the Late Iron Age with the regular appearance of the additional crops of oats and Celtic beans. These would also have helped to spread the risk, but there may have been another factor influencing diversification – the decline in fertility of free- draining light soils which had, by this time, been under cultivation for more than 2,000 years. Evidence in support of this is varied. At Ashville it was possible to chart a gradual increase of leguminous weeds commonly associated with decreasing levels of soil nitrogen, and similar data are becoming widely available from central southern Britain (Jones 1984, 121–2). It may also be that the increase in periodontal disease in sheep at Danebury is related to the declining quality of the pasture (Grant 1984a). The dynamics of soil fertility could provide an important constraining variable in the study of Iron Age society: it is a subject well deserving of further concerted research.

Towards the end of the Iron Age there is evidence of the growing popularity of bread wheat (Triticum aestivocompactum) – a variety which grows well on heavy silt or clay and is responsive to high nitrogen levels. Thus its increase may have been the direct result of the earlier colonization of heavy clay land. Significantly it has so far been found in quantity only in the south Midlands, at Bierton, Bucks., and Barton Court Farm, Oxon. – sites close to easily exploitable clay deposits. Its rise in popularity may be a factor more of regional specialization than of general change (Jones 1984, 123–4).

Apart from spelt and six-row barley other cereals were grown but on a much smaller scale. Rye (Secale cereale), another first-millennium introduction, occurs sporadically in Wessex, and oats (Avena spp.), of both the wild and cultivated varieties, are recorded from various sites, but only in small proportions until the Late Iron Age. Rye is a particularly hardy crop with a wide tolerance of soil types and is suitable for both autumn and spring sowing. Oats are less adaptable, preferring a milder and moister growing season. Since they are less hardy to frost they thrive better when spring sown. It was at the beginning of the first millennium that the Celtic bean (Vicia faba) made its first appearance in Britain and it became widespread later in central southern Britain. Since it has nitrogen-fixing qualities it is a useful break-crop to improve soil fertility, as well as being an acceptable food. Finally chess (Bromus spp.) occurs consistently in relatively small quantities, but this does not necessarily mean that it was sown as a crop in its own right.

The processes involved in reaping and storing the grain are open to debate. There is evidence from Hampshire to suggest that the crops may, at first, have been uprooted, accounting for the presence of rhizomes and seeds from short-growing weeds of cultivation among the deposits. The traditional way of gripping below the ear and cutting below the hand using small iron cutting hooks may also have been employed at least from the Middle Iron Age onwards when rhizomes and tubers are no longer found with the crop waste. The balanced sickle makes its first appearance in the Late Iron Age.

If the crop had been reaped when ripe the next process would have been threshing, but if a damp or slightly unripe crop had been cut some form of drying process would have been necessary, perhaps the artificial parching of the ears in order to drive off excess moisture and to loosen the grain from the husk to facilitate threshing. There is no direct archaeological evidence for this, but the discovery of quantities of charred grain on archaeological sites and the fact that grain was dried in specially constructed ovens in the Roman period has led to the belief that corn drying was widely practised in the Iron Age. It is generally assumed that temporary ovens built of cob were constructed for this process, but another possibility is that drying may have been carried out on a larger scale on skins spread over pre-heated flint nodules. The indirect heat which the flints would have imparted would have been quite sufficient to dry the ears to the necessary degree, with the added advantage of keeping the grain away from the direct source of heat, thus cutting down risk of combustion. That accidents did happen, however, is shown by quantities of charred grain from various sites, including deposits from pits at Itford Hill, Sussex, Fifield Bavant, Wilts., Totternhoe, Beds., Danebury, Hants, and Little Solisbury, Somerset. This type of process would explain the vast quantities of fire-crackled flints (‘pot-boilers’) which are found on most of the settlement sites, usually lying in thick layers mixed up with charcoal in the so-called ‘irregular working hollows’. Indeed the working hollows may well have been the sites where parching, among other activities, was carried out.

As soon as the ears were dried, they would in all probability have been threshed before storage, but some at least of the corn was stored in the ear as deposits found in the hillforts of Little Solisbury and Danebury show. Two different modes of storage are implied by the archaeological evidence: below-ground storage in pits and above-ground storage in timber-built ‘granaries’. Both types of structure constantly occur together, particularly on the chalkland of south-eastern Britain.

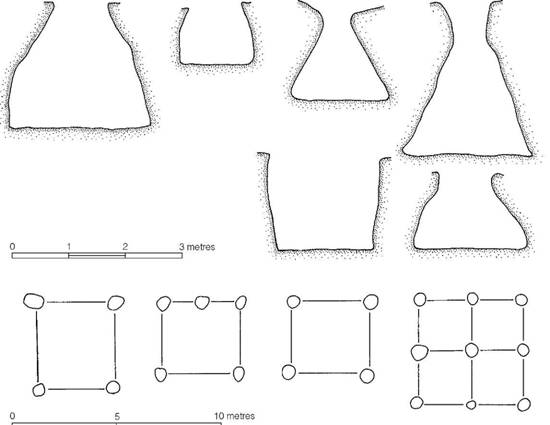

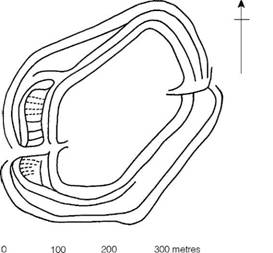

Pits were normally of beehive, barrel or cylindrical shape (Figure 16.2). In the early period they tended to be small, but by the third and second centuries BC they usually averaged about 2 m deep. Pits dug into the solid chalk were not necessarily lined. Although some form of wicker lining tends to cut down wastage through mould growth by keeping the grain away from the damp sides of the pit, the degree of caking together of the outer crust of grain would not have differed greatly between lined and unlined pits so long as an airtight seal of clay or marl was placed over the pit mouth. The effort involved in providing each of the grain storage pits with a wicker lining may well have been considered unnecessary – at least in the chalk areas, where the sides were firm and tolerably dry. Wicker linings have, however, been recorded at Dane’s Camp, Worcs., Poxwell, Dorset, and Worlebury, Somerset, but there is nothing to show that these pits were used for storing grain rather than other commodities. Some pits were lined with dry-stone work, but these are restricted to areas where stone commonly occurs. On the Isle of Portland about seventy stone-lined pits of beehive shape were discovered, narrowed at the top so that they could be easily closed by a single slab. One of them contained a mass of carbonized grain. Various types of flooring have also been recorded, ranging from stone and wood to clay and sand.

A variety of pit forms is known, no doubt reflecting an equally wide range of function in addition to grain storage. Some, lined with clay, may have served for water storage, being linked by gullies to the eaves-drips of roofs; some were perhaps vats for such processes as tanning; while others may have been used as larders where dried or smoked meat may have been stored.

The second type of storage structure is the so-called ‘granary’ represented now by settings of four, five, six, or more rarely nine posts (Figure 16.2). These are usually supposed to have consisted of square or rectangular timber buildings, averaging 2.5–3.0 m in overall length, the floors of which were raised above ground level to allow the free circulation of air beneath and to prevent rodents from eating the stored supplies. Granaries occur widely over most of south-east Britain and into the Welsh borderland. Frequently, as at Little Woodbury and Walesland Rath, they were built on the periphery of the settlement, often against the boundary, to keep them as far removed as possible from the domestic activities of the settlement and the potential threat of fire, but at Gussage All Saints they cluster in the centre. Granaries have also been found in a number of hillforts (Gent 1983): at Danebury, Hants, for example, several rows of regularly spaced buildings separated by streets were restricted to one part of the fort, implying that a special area had been reserved for this type of storage activity: a similar pattern is apparent in some of the forts of the Welsh borderland. Not all of the four- or six-post buildings were necessarily granaries; some may have been sheds for storing a range of equipment or products, others may have served as accommodation or cooking shelters. But in all probability they were built as grain stores, whatever secondary uses they were later put to.

Figure 16.2 Storage pit profiles and granary plans from Danebury, Hants (source: Cunliffe 1984a).

The problem now arises as to how pits and granaries related to the storage needs of the community. It used to be thought that the seed grain, which would have amounted to probably about one-third of the crop, was stored in the granaries, while the corn for consumption was parched and tipped into pits. A series of experiments has shown, however, that there is no preservative advantage to be gained in parching grain before pit storage; moreover, the germination rate of grain stored below ground was found to be in excess of 90 per cent (P.J. Reynolds 1974). In other words, there is no reason to suppose that all seed corn was kept through the winter in granaries since it could equally as well have been stored in pits. Further experiments showed that for pit storage to be successful it was essential to keep the seal airtight. This would argue against the use of large pits as silos for consumption grain, for once they had been opened it would have been necessary for the contents to have been emptied quickly in order to prevent degeneration. Rapid use could, however, have been achieved if the contents of each pit was common property to be shared out between all members of the community, or was used for exchange for other goods. Clearly the problem of grain storage is fraught with imponderables, but on balance it is simplest to accept the granaries as stores for the consumption cereal while the pits were used for the seed grain.

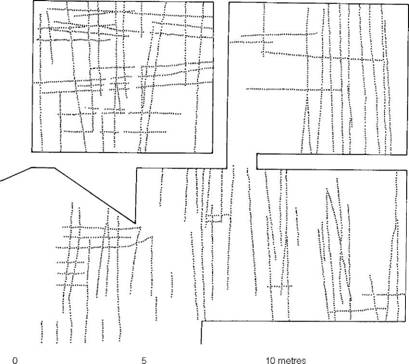

Figure 16.3 Plan of plough ruts discovered beneath a lynchet on Overton Down, Wilts. (source: P.J. Fowler 1967).

With the approach of spring the flocks and herds which throughout the winter would probably have been allowed free access to the fields, except those winter sown, would have been driven off to the fallow and to the upland pastures, while fields were further manured with household refuse brought out of the homestead.

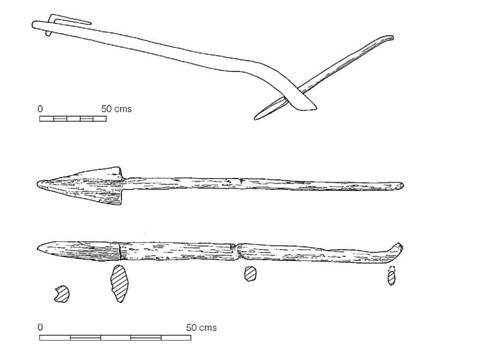

If the fields had been heavily grazed or trampled by animals, ploughing may have been unnecessary. In most cases, however, ploughing was undertaken using the simple iron-shod crook or bow ard (without a mould-board to turn the sod), the effect of which would have been simply to scratch a furrow in the soil (Figures 16.3 and 16.4). The excavation of Celtic field surfaces in southern Britain is now bringing to light evidence of actual ploughing in the form of the bottoms of the individual furrows scored into the bedrock. At Overton Down, Wilts. (Figure 16.3), the remnants of furrows belonging to at least five ploughings have been examined. Although the pattern is necessarily incomplete, because the ard did not always bite deep enough to scratch the chalk, sufficient survives to show that the individual furrows were about 30 cm apart, and that in all probability the field was ploughed in two directions at right angles, to break up the soil sufficiently for sowing. Very approximate estimates for the work involved in each ploughing can be arrived at by considering an average-sized Celtic field about 64 m square, ploughed by an ard drawn by two oxen travelling at about 3 km an hour. It would take between six and eight hours to complete the area: in other words, a field could be ploughed in a day. The Overton Down field is not necessarily of Iron Age date (it could belong to the Roman period) but there is little doubt that the practices recognized there are exactly comparable to the pre-Roman situation. Indeed, evidence is now accumulating from various parts of the country to show that this basic system of arable production dates back to the second and third millennia BC, and probably remained little changed until the end of the Roman period.

Figure 16.4 Plough head and stilt from Milton Loch Crannog, Dumfries and Galloway Region (source: C.M. Piggott 1955).

In addition to using the ard for cultivation, hand-digging with a wooden spade was undertaken. At the second-millennium site at Gwithian, Cornwall, individual spade-marks were found in the headland of the ploughed fields. In northern Britain, between the Tyne and the Forth, extensive cultivation plots have been identified in upland areas composed of parallel banks of soil between linear ditches – a system that has been called cord-rig (Topping 1989a and b). It is possible, but by no means proven, that the banks were originally created with the spade. Some examples show ard marks on the surfaces beneath but these could have been caused during the use of the strips rather than the construction.

Frequently cultivated Iron Age fields, where they can be defined on hill-slopes, are usually squarish in shape and bounded by lynchet banks created largely by the process of ploughing, which encouraged particles of soil to move down the slope to form a positive lynchet, at the lower edge of ploughing, leaving a negative lynchet at the upper edge. That the lynchets formed at all implies the continuous ploughing of defined areas over a period of many years. Little is yet known about the mechanism of primary land division, but fences, hedges, marking stones or posts, and gullies or setting-out banks were all used to define the original limits of the fields. After the first ploughing or two the land was probably cleared of large stones and flints, which would have been thrown to the edges of the fields thus adding to the permanence of the boundaries. As ploughing continued, lynchets increased in size until gradually the stage was reached when the uncultivated slopes of the banks themselves would have been extensive enough to be used as strips of waste between arable plots. As a general rule, therefore, it may be said that as arable farming developed within a given area of hill slopes, the actual arable hectareage must have decreased with the growth of lynchet slopes. If the thick soil of the lynchets was allowed to support the scrub and woodland which would tend to grow naturally, the areas of potential pannage and forage for pigs and cattle would have gradually increased. Such swathes of scrub would also have served as valuable wind-breaks and, if properly coppiced, would have provided a continuous supply of timber for wattlework and other purposes much as the bocage of northwestern France still does today.

On the low-lying gravel soils fields were bounded by ditches and presumably hedges. In areas such as this constant ploughing would not have led to the formation of lynchets: in consequence the only archaeological traces to survive are buried ditches, which are frequently recorded on aerial photographs. In upland areas stones cleared off the arable plots were frequently piled into mounds or low ridges to form clearance cairns.

The colonization of wasteland was systematic in many areas. The fields around the Farley Mount settlement have a distinctly well-planned regularity about them, and around the hillfort of Sidbury, Wilts., hundreds of hectares of ordered field systems are known, pre-dating linear earthworks linked to the fort. It is difficult to resist the assumption that at times during the first millennium massive and concentrated programmes of land clearance and distribution were undertaken.

Animal domesticates and their management

Arable farming on the scale outlined above could not have been maintained without considerable flocks and herds to provide manure for the fields. Cattle and sheep were reared in large numbers while pigs played a subsidiary role (Maltby 1996). The cattle were the small Celtic shorthorns (Bos longifrons), about the size of modern Dexter cows; the sheep were a small straggly variety, not unlike the modern Soay type. Goats were also kept but it is difficult to distinguish them from sheep on the basis of their skeletal remains. In addition to the three basic farmyard animals, dogs were usually present, probably as pets and work-animals, and small horses or, more correctly, ponies about 12 hands (1.2 m) high, rather like an Exmoor pony, were reared mainly for traction.

Statistics based on the quantities of animal bones found on occupation sites give some idea of the relative importance of the different species, but it must always be remembered that the bones can do no more than represent animals butchered at the homestead and possibly joints of meat brought in from elsewhere. If, for example, sheep were kept solely for wool, their bones would tend to be scarce in such deposits. In broad terms, however, there appears to have been a gradual increase in the numbers of sheep relative to cattle during the first millennium. At the late second- millennium Cranborne Chase sites of South Lodge Camp, Martin Down Camp and the Angle Ditch, the percentage of cattle in the total faunal assemblage varied between 48 and 67 per cent (the lower figure being abnormally depressed by exceptionally large numbers of deer and dogs) while in the second- to first-century BC settlement at Glastonbury sheep outnumber oxen by almost seventeen to one. It is of course possible that the assemblages are affected to some extent by the different functions of the sites or by environment, but the general trend towards sheep- rearing is clear enough. The same story is told by the collection of bones from Eldon’s Seat (Encombe), Dorset, where between the seventh and fifth centuries the proportion of sheep increased from 40.7 to 61.7 per cent and cattle correspondingly declined from 50.6 to 28.3 per cent. Figures for the south Midlands are less reliable, but at Twywell and Ravenstone, where statistics are available, sheep outnumbered cattle by nearly three to one. In the north-east, however, cattle remained dominant in number well into the Late Iron Age.

The relative increase in the numbers of sheep, in the south, throughout the first millennium is probably related to the spread of downland arable. To maintain the enormous hectareages of fields farmed during the Iron Age, flocks and herds would have been essential in providing manure for the land. Sheep would have been the obvious choice, for not only could they survive for long periods on the downs without water, but they were also relatively easy to maintain over the autumn and winter. From September until December they could be turned loose on the stubble without the need for special feeding, and from December until March or April, when the pastures began to grow again, straw fodder carted to the fields would have been sufficient to keep them alive. For the remainder of the year, from April to August, there would have been ample pasture for the flocks to grow fat on in the fields left fallow and on the open downland. The symbiosis between sheep and fertile arable land cannot be overstressed: it is no exaggeration to say that without large flocks, grain production, on the level attained in the south, would have been impossible to maintain.

Sheep also had other uses: at various times they could provide wool and milk, and eventually meat, bone, sinew and skin. Relatively few were slaughtered in the first year – only 9.2 per cent at Encombe and about the same percentage from Hawk’s Hill, Surrey – and over 40 per cent of the flock lived to more than 2 years of age at both sites. These figures were not universal, however, for at Barley, Herts., 39 per cent were killed in each of the first two years. One possible explanation is that at Barley the slaughter of yearlings reflects a reliance on sheep as a meat source, the carcasses being salted down for winter, while in the south sheep were kept more for their wool and manure, mutton being of secondary importance. Clearly, there were regional variations in farming practice which need to be worked out in detail when further data become available. In spite of the numerical advantage of sheep, mutton was not consumed in very large quantities compared with beef. The average weight of a sheep was only about 57 kg, while that of a cow might be as much as 410 kg. Thus at Hawk’s Hill the sheep at 57 per cent produced only 23 per cent of the meat supply while the cattle at 17 per cent yielded 53 per cent. The figures are of course approximate, but they emphasize the fact that for the most part the Iron Age farmers of the south, in so far as they ate meat, were beef-eaters.

Cattle were far more difficult to maintain than sheep. They needed constant watering and from December until March they would have required protection from the weather in corrals and enclosures, and in byres in more extreme climates, and provision of regular feeds of straw, hay, leaf fodder or silage. It would seem unlikely that the beasts were brought into the actual farmstead enclosures unless special provision was made to keep them well clear of the domestic fittings and houses. At Little Woodbury, Wilts., no internal divisions are known, but the antennae ditches in front of the main entrance could well have enclosed a stockyard. The advantages in having the stock close by during the winter months are obvious: not only could they be protected from raiders and wild animals, but the constant foddering and watering which would have been necessary could more easily have been carried out from the home farm. Foodstuffs for the cattle would have proved no problem; hay would have been important, so too would leaf fodder cut in the spring and stored throughout the summer. Nor must the significance of straw be overlooked. If, as we have assumed, the harvest was undertaken before the cereals had fully ripened, the straw would have retained a far greater nutritional value. Indeed, this may be one of the reasons for the early harvesting which necessitated drying and roasting before threshing. In some upland areas, where the ripening season was short, barley could have been cut green and stored in the ear with the stalk attached to provide animal feed. Straw and hay may have been stacked on the two-post racks or small four-post standings which occur so frequently. Leaf fodder was probably stored in a similar way or in underground silos. Some of the grass crop may also have been turned into silage, perhaps in pits.

In addition to their value as meat- and milk-producers, cattle were used for many kinds of tractions, in particular ploughing. For these reasons, the tendency was to keep the herd to maturity. Of the thirty-nine individual animals recognized at Hawk’s Hill, only three were killed in the range of 0–6 months and sixteen were older than 3 years when they died or were slaughtered. At Eldon’s Seat the figures were comparable: of the twenty-eight represented, seventeen had reached maturity. Apart from the plough teams and the bulls kept for breeding, the main herd was probably composed of cows kept in milk during the spring and summer months, when they would have been allowed out to browse in the forest fringes, the pastures and the steep faces of the lynchets. Their very presence implies the provision of water in reasonable quantities, possibly collected and conserved in dew-ponds. No certain traces of Iron Age dew-ponds have been recognized, but their existence on the downs can hardly be doubted. At the settlement on Park Brow, Sussex, a structure suggestive of an ancient dew-pond was found in close relationship to the trackway which joined the various sites and another possibility has been noted in Micheldever Wood, Hants, close to a settlement. If they are indeed Iron Age in date, their siting would have suited them admirably to the pastoral needs of the community.

Pigs of a domesticated variety played a significant part in the economy. Normally numbers were low: 3.5 and 4.0 per cent in the two periods at Eldon’s Seat, 1, 0 and 9 per cent on the Cranborne Chase sites, but rising to 22 per cent at Hawk’s Hill and 33 per cent at Highfield, near Salisbury, Wilts. The range is interesting, since it must indicate a considerable variation of practice in the reliance placed on the animal. Settlements close to tracts of woodland on nearby clay soils, in river valleys or on steep hangers, would have been able to maintain large herds of swine without much trouble, but where pannage was sparse, on the more open downs, pig rearing would have been difficult and consequently numbers were much lower.

Horses have been found on most sites but usually only in small numbers around 10 per cent of the total. They are almost invariably mature animals 10–13 hands high and would have been used for traction and riding, though there is evidence of butchery presumably implying that horses were sometimes eaten. The absence of immature animals suggests that horses were not bred but were captured in the wild and trained (Harcourt 1979, 158). At the hillfort of Bury Hill, Hants, the percentage of horse bones was very high, some 27 per cent of the total. This, together with the discovery here of large quantities of horse and vehicle gear, suggests that the training of chariot teams may have been a specialist activity for the brief period of the fort’s existence.

Hunting appears to have been of little economic significance. Red deer, roe deer and fallow deer are all recorded on settlement sites, but since shed antlers were collected for tool-making, percentages are unreliable. Various birds are known, including duck, swan, raven, quail, wood pigeon, teal, goose, blackcock and red grouse(?), and occasionally small mammals like water voles and hedgehogs turn up in reliable archaeological contexts; fish are very rarely found. On the coasts, however, shellfish were collected in great quantity.

Dogs were general-purpose animals used for hunting, herding and probably as pets. They occur widely, but little reliable work has yet been carried out on the various breeds represented. At Highfield about twenty dogs were found (22 per cent of the total animal bones), of which five were of foxhound type, one like a retriever and one rather smaller than a fox terrier. Evidently selective breeding was by this time well under way. The large number of dogs from Highfield is puzzling. The site does not appear to have religious connections, which could have accounted for ritual killings, but some of the bones showed knife-cuts possibly resulting from the collection of sinews, which may be thought to indicate some form of industrial activity.

The importance of animal husbandry to the economy was considerable. It is therefore not surprising that specialized structures were designed and built to cope with the problems of looking after the flocks and herds. These will be more appropriately considered in the regional reviews to follow.

Some regional regimes

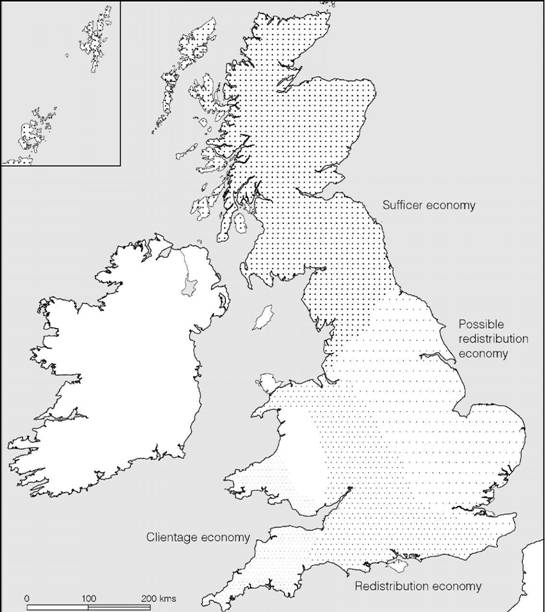

Sufficient will have been said in the preceding brief overview to show that there was considerable regional variation. This may be due to a number of factors: chronological differences, variation in regional strategies and specialization between contemporary sites within a given region. Not all regions are equally well known but evidence is fast accumulating and some indication of the different subsistence patterns may be sketched out.

Central southern Britain

Central southern Britain is dominated by the chalklands of Wessex which tend to impose a broadly similar set of environmental constraints over much of the region. Standing back from the considerable detail that is now available, various general trends emerge. In terms of the agricultural regime it is possible to recognize an increase in the scale of arable production accompanied by a diversification of crops and a movement into more marginal areas. This may have been occasioned in part by an overall increase in population and by a degree of soil exhaustion on the lighter soils which had been cropped for 2,000 years. Alongside this there is evidence to suggest a dramatic rise in the numbers of sheep in the first half of the first millennium, reaching a high by the fifth century which was maintained for the rest of the millennium. The relative increase in the percentage of sheep does not imply a decline in the actual numbers of cattle: it may simply be that large flocks of sheep were run to maintain the fertility of the thin upland soil which by this time was degenerating.

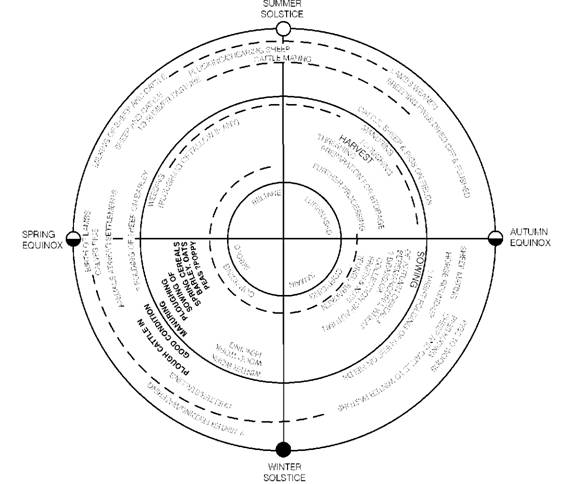

That a careful balance was kept between cereal growing and stock rearing is axiomatic. The two halves of the regime were entirely interdependent (Figure 16.5). A field of stubble turned over first to cattle, then to sheep and finally to pigs, in the late summer or early autumn, would have provided nutrients to all three while the land benefited from their manure. Threshing waste was a useful additive to animal feed during the winter, and in the spring, when the majority of the storage pits were opened for seed, the caked crusts of partially fermented grain from around the pit edges would have provided a rich food source for penned beasts at the crucial time in the run up to lambing and calving.

Figure 16.5 The farming year: a reconstruction based on evidence from settlements in the Danebury region (prepared by Gill Campbell and Julie Hamilton in Cunliffe 2000).

Each animal would have had its particular uses, but none was more valuable than the pig as a living store of readily accessible fat and protein. The pig could turn virtually any waste into calories: inedible acorns, bracken, grubbed-up roots and all the offal, still births and excess milk generated by husbanding the flocks of sheep and herds of cattle.

It seems highly probable that the basic diet comprised cereals and milk products, with meat as a luxury. Herds of cattle were too valuable to slaughter: they were probably a sign of status and wealth and thus numbers were important. The prime function of the herds was therefore to provide milk and to reproduce. Sheep on the other hand were more expendable. Large numbers were needed to maintain the fertility of the fields, though wool and milk would have been useful by-products. When the herds and flocks needed culling there was meat to be had, otherwise the only readily available source, having little bearing on other social and economic systems, was the pig. All swine surplus to the needs of the breeding herd could be culled at will. The model proposed is not unlike that prevalent among many peasant societies throughout much of Europe before the Industrial Revolution. For the Iron Age it is plausible but, since the faunal and floral data are impossible to quantify in a way that allows direct comparison, the model cannot be tested.

Sufficient data are now available from the Wessex chalklands to allow a detailed picture to be sketched of the changing economy of the region during the first millennium BC. The totality of the archaeological evidence allows five stages to be defined which may be briefly summarized:

- c. 1400-900 BC (Middle-Late Bronze Age) Land reapportionment: some linear boundaries and coaxial field systems; scattered farmsteads.

- 900–600 BC (Late Bronze Age–Earliest Iron Age) Linear earthworks (ranch boundaries): hill-top enclosures, middens, scattered farmsteads.

- 600–350 BC (Early Iron Age) Linear earthworks continue; early hillforts proliferate, scattered farmsteads.

- 350–100 BC (Middle Iron Age) Some major linear boundaries maintained; many early hill-forts little used, few developed hillforts maintained, some nucleation at hillforts but some scattered farms continue.

- 100 BC–AD 50 (Late and Latest Iron Age) Reordering of landscape; abandonment of many hillforts.

The social and political implications of these changes will be considered in more detail later (chapter 21). Here we will focus on their implications for the food-producing economies.

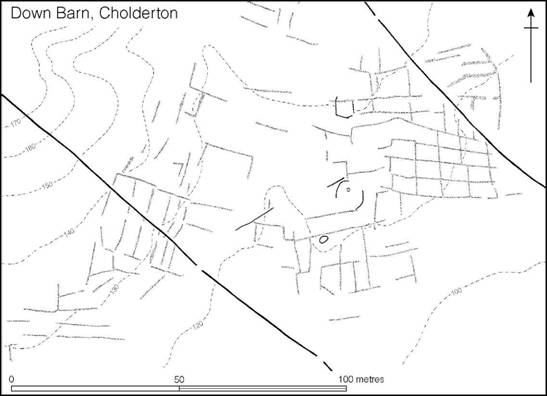

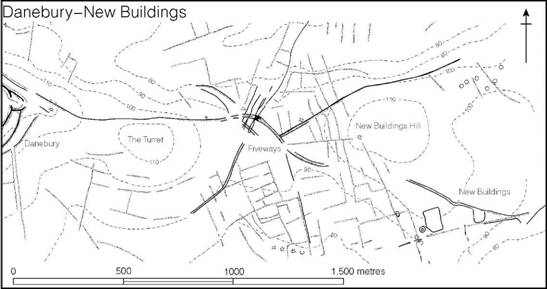

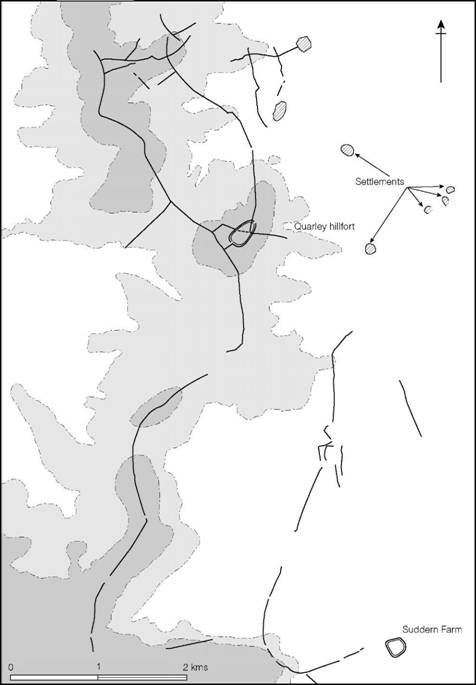

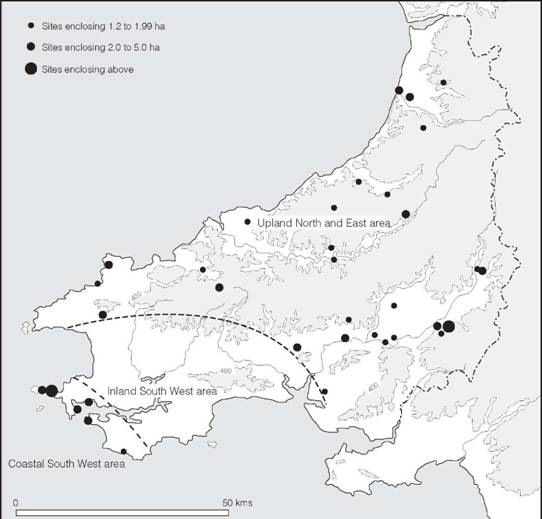

The period from c. 1400 to c. 900 saw the extension of arable agriculture over very considerable tracts of landscape. In some areas it is possible to identify major programmes of land allotment which seem to have been carried out as a single programme under a coercive authority such is the order and regularity with which the fields are laid out. Many examples have been identified but among the most impressive is the system close to Quarley Hill where the hill slope has been divided into at least four large strips 200–300 m wide, each subdivided into fields, the total system covering some 90 ha (Figure 3.10). Others are known at Down Barn, Cholderton (Figure 16.6), Danebury–New Buildings (Figure 16.7) and Woolbury (Cunliffe 2000, 149–62). The overall impression given by these projects is that society was working co-operatively to impose a stable agricultural regime on the landscape and to create a degree of permanence in the form of visible and agreed boundaries.

A number of contemporary settlements have been excavated (above, pp. 43–8). Black Patch, East Sussex, however, provides an insight into the workings of one of these family- or extended family-sized units. Black Patch was an unenclosed settlement composed of several small houses, the occupation of which appears on the evidence of radiocarbon dates to have taken place within the period 1400–900 BC. A thorough analysis of the settlement detritus shows that barley occurred in quantity, but there were also significant quantities of emmer and spelt wheat. Bone preservation was poor but sufficient to show that cattle outnumbered sheep by almost two to one. The economic model proposed by the excavator (Drewett 1982, 392–9) suggests that settlements of this type were largely self-contained but were able to produce a small surplus for redistribution in local networks of exchange. The evidence from elsewhere, in Wessex, is consistent with this picture.

Figure 16.6 Early coaxial field system cut by linear boundaries at Cholderton, Hants (source: Cunliffe 2000).

The second stage in the development of the Wessex landscape (c. 900–600 BC) is characterized by the imposition of an extensive system of linear earthworks, often called ‘ranch boundaries’, which run for many kilometres across the landscape, frequently cutting indiscriminately across earlier field systems (Figure 16.6) and evidently putting out of use areas previously used for cereal growing. These boundaries often run along ridges, with others branching from them to define large blocks of territory extending from the high downland to the river valleys (Bradley et al. 1994; McOmish et al. 2002, 56–66). Where sectioned these ranch boundaries usually consist of a V-profile ditch with the spoil thrown on one or both sides, and in some cases, like the Quarley linear, show clear evidence of having been renewed on many occasions. Sometimes, as in the case of the Danebury linear, there were two ditches 3 to 4 m apart. The upcast was probably thrown into the centre and may have formed the basis for a wide hedgerow. Other boundaries are less recognizable. At Portsdown Hill, near Portsmouth, the boundary was a gully flanked by timber palisades. A comparable example was found at Winterbourne Dauntsey, Wilts. Slight features of this kind leave little mark on the present landscape and may well pass unnoticed except when exposed in excavation.

Figure 16.7 The fields, boundaries and enclosures at New Buildings, near Danebury, Hants (source: Cunliffe 2000).

The Wessex linears are particularly well represented in the vicinity of the hillforts of Sidbury, Quarley, Danebury and Woolbury. At Quarley Hill excavation has demonstrated a sequence of development culminating with the superimposition of a hillfort, dating to the fifth century, on part of the system of ditches converging on the hill-top (Figure 16.8). The main Quarley linear, which runs along the ridge close by, continued to function as a boundary at this time and well into the Middle Iron Age (Cunliffe and Poole 2000g). Similarly at Ladle Hill, Hants, a linear boundary seems to precede the construction of a hillfort which remained unfinished (Figure 16.9). At Danebury, the later hillfort was constructed within an earlier hill-top enclosure which could be shown to be broadly contemporary with a major linear earthwork which was laid out across a pre-existing field system (Figure 16.10). Woolbury hillfort, Hants, can also be shown to be imposed on a linear earthwork (Cunliffe and Poole 2000a) (Figure 16.11) and it is quite probable that the hillfort of Sidbury, Wilts., was constructed at a focus of several linear earthworks. The evidence, then, is impressive in showing that focal points within the systems of linear earthworks were consistently chosen, several hundred years later, as locations for hillforts.

Contemporary with the initial layout of the linear earthworks, a number of hill-top locations were enclosed by an earthwork comprising a bank and ditch. These we have called early hill-top enclosures (above, pp. 378–82). Examples include Balksbury, Walbury, Danebury (outer enclosure), Martinsell, Bozedown and Harting Beacon. The most extensively excavated example is Balksbury, Hants. Here the earthworks and simple gate were twice refurbished during the two centuries or so that the site was in use. The interior was largely open apart from a number of small four-post structures, which could have served as fodder ricks, and a few lightly-built circular structures probably serving as shelters for those staying in the enclosure during certain periods in the year. Detailed analysis of the soil accumulation behind the rampart showed that it had derived from manure and cattle litter mixed with debris which had probably resulted from feasting (Ellis and Rawlings 2001, 87–8). Taken together the evidence strongly suggests that the enclosure was built for livestock management, the animals probably being driven there at those times during the year when the flocks and herds needed to be gathered for culling, castration, redistribution and possibly calving and lambing. The hill-top enclosures and linear earthworks clearly belong to a system involving livestock management on a large scale.

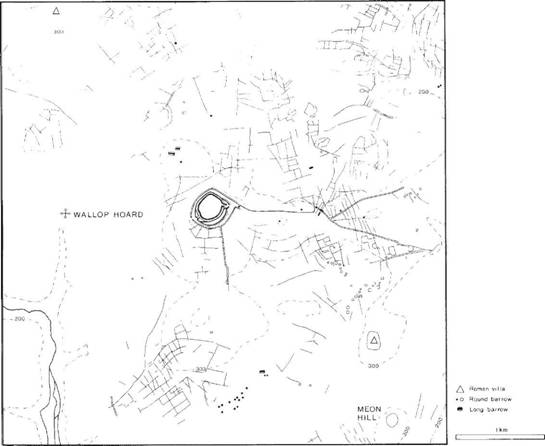

Figure 16.8 Quarley Hill, Hants, and its ‘ranch boundaries’ (source: author after Palmer 1984).

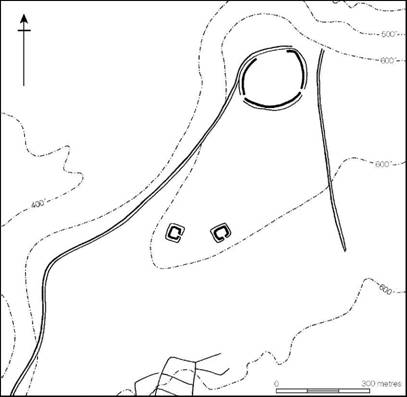

Figure 16.9 Rectangular enclosures and associated pasture land on Ladle Hill, Hants (source: S. Piggott 1931).

Another category of site needs to be considered in this context – locations where huge deposits of midden material were allowed to accumulate. One of these, at Potterne in Wiltshire, covered an area of 3.5 ha and was up to 2 m deep, encompassing some 40,000–50,000 cubic metres of deposit. At East Chisenbury a similar deposit was estimated to be some 65,000 cubic metres. A meticulous analysis of the Potterne midden has led the excavator to conclude that the site was a special location associated with a cattle-rearing society and visited by people on a regular but periodic basis. In other words it may have been a ‘central place’ drawing on a widely dispersed population who gathered at certain occasions during the year when feasting and religious celebrations were enacted (Lawson 2000, 266–71).

A third type of site relevant to the discussion is represented by the small rectangular enclosure on Harrow Hill, Sussex. The enclosure comprised a palisade set in a shallow bank with opposed gated entrances. Finds were sparse, but pottery of the eighth to sixth centuries was found together with an unusual quantity of ox skulls. The excavators estimated that if the density of bones found in their limited excavation was typical of the enclosure as a whole there must have been at least 1,000 oxen present. That the bones were almost entirely skulls hints at a ritual significance, but an alternative suggestion, not necessarily exclusive of the first, is that the beasts were collected here for slaughter, perhaps in an annual round-up, the carcasses being carried off to neighbouring settlements for consumption.

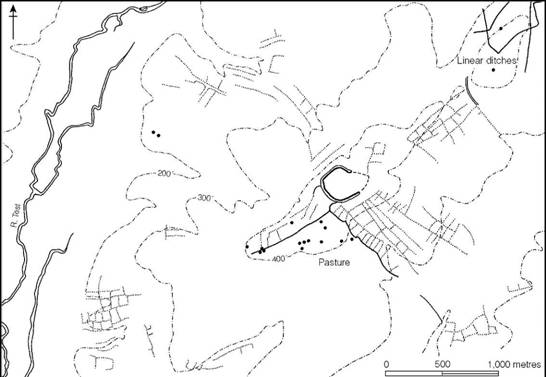

Figure 16.10 Arable and pasture land around Danebury, Hants (source: Cunliffe 1984a).

Sufficient will have been said to show that the period 900–600 BC saw the development of animal husbandry organized, it would appear, at a communal level. The animal bone evidence suggests that cattle were the most important resource (at least in terms of body weight) but large flocks of sheep were also managed. The relative importance of cereal growing to the economy is difficult to assess but the probability is that grain formed the principal food source together with dairy products, meat becoming available when flocks and herds were culled.

The crop remains recovered from Potterne show that wheat and barley were present throughout the occupation in roughly equal quantities and there was evidence for both autumn and spring sowing. The barley was of the hulled six-row type. Of the wheat both emmer and spelt were present. The same range of crops was present at the contemporary farmstead at Houghton Down, Hants, but here spelt was dominant with emmer present in only small quantities.

Figure 16.11 The landscape around Woolbury, Hants (source: author).

The third stage in the development of the Wessex landscape, 600–350 BC, saw the spread of hillforts (pp. 384–6) and the development of many farmsteads (pp. 239–44), while in the fourth stage, 350–100 BC, a number of hillforts ceased to be used though a few continued. Of these developed hillforts several, among them South Cadbury, Barbury, Danebury and Maiden Castle, seem to have become densely occupied and may have provided services for a larger region around. For the purposes of this discussion it is convenient to treat the two stages together, since the economy shows a continuous development over this time, but where necessary to refer to the Early Iron Age (600–350 BC) and the Middle Iron Age (350–100 BC).

If we stand back from the mass of detail available, two broad trends emerge: a considerable increase in the percentage of sheep represented in the animal bone debris and the sudden appearance of large storage pits and storage buildings as persistent features in settlements and hillforts. If, as we believe, the prime function of the storage pit was to keep the seed corn between harvests and the storage buildings served as granaries for cereals for consumption, the implication would seem to be that there was a dramatic increase in the volume of cereals produced. We have suggested above that the increase in the numbers of sheep may have been related to the expansion in the amount of arable land brought into cultivation, since sheep were the ideal means of manuring upland arable.

The evidence for crop production throughout the period shows a heavy reliance on spelt wheat and six-row hulled barley, with emmer declining into insignificance. A comparison of the residues from settlements excavated in the neighbourhood of Danebury suggests a change in cropping regime over time: in the Early Iron Age a mixed crop of spelt and barley (maslin) was sown in the autumn, but during the Middle Iron Age, although this practice continued, it now seems that crops of pure barley were being sown in the spring (Campbell 2000). How widespread this phenomenon was it is difficult to say. A comparison of grain production and crop processing from two settlements close to each other, at Micheldever Wood and Winnall Down, both in Hampshire, shows that variation between sites might be expected (Monk and Fasham 1980). Such differences could reflect a number of factors ranging from local soil potential to social status.

The position of the hillforts within the socio-economic system is still a matter of debate, not least because very few have been adequately sampled, but from the beginning, in the Early Iron Age, Danebury was occupied on an intensive basis. In addition to streets, numerous houses and a shrine, large numbers of four- and six-post storage buildings and storage pits packed the interior. The potential grain storage capacity was very considerable. Leaving aside the numerous ‘granaries’, the number of pits per unit area was about four times greater than at the average contemporary farmstead. The implication would seem to be that the hillfort may have provided storage capacity for the surplus grain of the larger community. The various deposits excavated in Danebury produced a varied assemblage of seeds and threshing debris, showing that a full range of processing had been carried out within the fort and that crops had been brought in from several different ecological zones. This supports the suggestion that the fort may have become the territorial focus for processing and storage.

The animal bone assemblage from Danebury in general mirrors that from the neighbouring farmsteads as far as the percentages of the different species were concerned. Simply counting bones indicates that sheep were the most common, at 60 per cent, followed by cattle at 20 per cent and pig at 15 per cent, with smaller numbers of dog and horse, but in terms of meat yield beef came first, 67 per cent, with mutton and pork being respectively 23 per cent and 10 per cent. However, that meat production was not the prime aim of husbandry is shown by the fact that animals were not killed when at the optimum ages to provide the best meat. Instead the culling of cattle and sheep was geared to the maintenance of large and vigorous herds and flocks. The detailed analysis of the faunal assemblage from Danebury has yielded a great deal of information about Iron Age husbandry (Grant 1984a, 1991), the most significant points, for the present discussion, being those which reflect upon the special use to which the hillfort was put. The high percentage of neonatal deaths among sheep and cattle strongly suggests that lambing and calving were carried out in close proximity to the fort, quite probably in the corrals created by the outer earthworks immediately outside the defences. There would have been much sense in driving the pregnant beasts into the protection of these enclosures at the beginning of the spring breeding season. Labour needed to provide special feed would have been minimized and predators more easily kept at bay. Comparison with chalkland farmsteads is not straightforward because samples are so much smaller and detailed statistics not always readily available, but at the farmsteads in general there were proportionately fewer deaths within the first weeks after birth. If this impression is sustained by further work then it might indicate that hillforts like Danebury served as foci for lambing and calving.

The gross figures of animal bone percentages quoted above are useful as a generalization, but they obscure a far more complex underlying pattern since they conflate some 450 years of occupation during which there were significant changes in the social position of the fort. In the Early Iron Age the fort was occupied by a large community at the same time as a number of farmsteads were in use in the immediate vicinity. In the Middle Iron Age the population within the fort had increased considerably while there was a corresponding abandonment of farms within a 10 km range. The Late Iron Age saw the fort population decline dramatically as people moved back to the countryside. Such changes in status seem to be reflected in the percentages of the different species present. Another factor which may distort the figures is the selection of specific animals as propitiatory offerings placed in pits (below, pp. 570–2). If these are excluded and we consider only bones from general layers then a somewhat different picture emerges:

The Middle Iron Age profile stands out as being far more biased in favour of sheep, with proportionately fewer cattle. There is also a significant increase in horses in the Late Iron Age.

A sheep-based regime would have been far easier to run from the hillfort during the period when the population of the region seems to have lived in the fort. The increase in the number of horses in the latter part of the Iron Age is supported by statistics from other sites. At Bury Hill, Hants, not far from Danebury, the latest phase of occupation, dating to the late second and early first centuries BC, produced an exceptionally large number of horses (27 per cent of the total animal bone assemblage) together with numerous harness- and vehicle-fittings. It is tempting to see this as a reflection of the importance of horse-drawn chariots, the possibility being that the horses were trained and the chariots were built by the inhabitants of the fort. At the settlement site of Gussage All Saints, Dorset, horse remains were also high at between 5 and 10 per cent, and the age profile differed from that of the normal farmyard animals in that new born and young individuals were conspicuously absent. One interpretation of this is to suppose that horses were allowed to breed in the wild on the wastelands and were annually rounded up for selection and subsequent training. The proximity of Gussage to the heathlands of the New Forest is suggestive; so too is the workshop debris representing the mass production of horse gear on the site.

The interrelationship of animal husbandry and crop production is well represented in the field archaeology of the Middle Iron Age. We have already mentioned the linear boundaries of the Later Bronze Age, which seem to have continued as significant landscape features throughout much of the period and the animal pens attached to hillforts. Many of the forts were close to large areas of pasture land which would have provided feed for livestock during the summer months. At the Trundle, Sussex, the pasture lay all around the fort, and was separated from arable land by a series of earthwork boundaries crossing the spurs and so sited that the browsing beasts would always have been within sight, and therefore the protection, of the fort. At Danebury (Figure 16.10) a large hectareage of pasture visible from the fort lay between a linear earthwork and a block of arable, through which a droveway led to inner corrals around the fort which themselves provided 11 ha of well-protected pasture. A variation of this arrangement can be seen on Stockbridge Down, near Woolbury (Figure 16.11), where two linear boundaries run up to the fort from the south, defining an area of pasture and dividing it from neighbouring arable fields.

Stock management systems are also well in evidence around farmsteads. The settlement enclosures at Gussage All Saints are intimately bound up with trackways and boundaries running for many kilometres (Wainwright 1979, figure 111), and much the same complex system can be found around many of the settlements on the downlands between the rivers Test and Bourne (Palmer 1984). It was during the Middle Iron Age that a new type of settlement configuration, the banjo enclosure, appeared in central southern Britain (pp. 244–7). The characteristics of the banjo, the long ditched causeway leading from a linear boundary to the enclosure, if divided by temporary fences and hurdles, would have been of considerable value in sorting out stock. The very numbers of these enclosures scattered over Wessex might suggest a reorientation of the economy to more pastoral pursuits. It is difficult to prove on present evidence, but if it were so, such a change could be seen as a response to the progressive impoverishment of the thin downland soil for which there is firm botanical evidence (Jones 1984).

The fifth phase of the Wessex sequence, covering the first century BC and the early first century AD, is not well known, largely because of the paucity of well-published excavations of this period. But there was a marked change in settlement pattern: hillforts generally go out of regular use and enclosed farmsteads give way to agglomerations of ditched enclosure (pp. 248–50), though the banjo type, once established in the Middle Iron Age, continues to be used.

What caused these changes it is difficult to say and indeed there may have been a number of interacting factors. One may have been the progressive degeneration of the traditional farmland, which is thought to have been reflected in the increasingly weedy nature of the crops, and to have led to the opening up of new ecological zones and the introduction of new crops like bread wheat (Jones 1984).

Another factor may have been the development of long-distance trade routes within the Roman world through the port of Hengistbury Head in Dorset. As we will see (pp. 474–83), a lively trade sprang up in the early first century BC. Among the commodities collected there for export was grain which, according to the weeds of cultivation recovered, came from a variety of inland environments. The animal bones indicated an unusually high percentage of cattle, which might have been amassed there either for export on the hoof or to be rendered into leather – a desirable commodity in the Roman market. It is difficult to judge from the archaeological evidence how intensive or how long-lived the trade was, but even a modest level of export over a few consecutive years will have had some effect on the local systems.

The Midlands

Our understanding of the Iron Age economy of the Midlands has been revolutionized by a series of large-scale excavations accompanied by detailed environmental investigation in the Upper Thames valley. Of these Ashville, Barton Court Farm, Appleford, Mount Farm, Mingies Ditch, Roughground Farm, Watkins Farm and Farmoor have been fully published, while Claydon Pike, Hardwick and Gravelly Guy are reported in more summary form. Several general overviews considering the economic implications of these sites have been published (especially Robinson 1984; Hingley and Miles 1984; Jones 1984; Lambrick and Robinson 1988).

A summary of the major settlement types has been given above in chapter 12. Suffice it to say that three broad ecozones can be defined: the upland areas of the Cotswold dip slope; the well- drained gravel terraces of the Thames and its tributaries; and the river flood plain. Each supported its own range of settlement types and each offered a different resource potential for exploitation. Little is yet known of the economy of the dip slope settlements but in general form they resembled the banjo enclosures of Wessex and are most likely to have been single family farmsteads. The valley sites are more diverse, and there is clear evidence of a degree of trans- humance from the gravel terrace settlements to temporary summer establishments on the flood plain so that livestock could range across the hay meadows (Lambrick and Robinson 1979, 1988).

A detailed assessment of the crop waste suggests that a distinction can be made between sites on the well-drained second terrace, such as Ashville and Mount Farm, Oxon., and first-terrace sites like Claydon Pike and Hardwick. The second-terrace assemblages were rich in cereal grain while those of the first terrace were dominated by weeds and chaff. This may suggest that the latter were the production sites where the crops were cleaned and threshed, while the former received the processed grain. If so, then the differences must be either purely functional or are status-led. In either case it suggests a high degree of specialization within a narrow environmental zone and implies a mechanism for redistribution. It may be that special redistribution centres developed within the system: a site like Gravelly Guy, which is characterized by an exceptionally large number of storage pits, has some claim to be such a centre. For settlements on the flood plain, like Mingies Ditch, one must suppose that the grain consumed was grown on the gravel terrace nearby, where it is possible that the community had cultivation plots.

Sheep, cattle, horses and pigs were reared. The percentages of sheep were low compared to the chalkland zone but this is only to be expected. Sheep do not fare well in damp situations: they are prone to foot-rot and to liver fluke, as the discovery of the molluscan host to liver fluke at Appleford reminds us. Small flocks were however kept. They seem to have been composed largely of mature females, and the scarcity of bones of young animals suggests that the flocks were probably raised on the upland calcareous soils and brought to the drier pastures of the valleys during the summer months. Cattle were better suited to the valley environment and invariably occur in the highest numbers. However at sites like Ashville and Barton Court Farm bones of very young animals are rare. This would seem to imply that, as with sheep, breeding took place elsewhere.

But this may be an oversimplification. A careful analysis of the animal bones from the flood plain site of Mingies Ditch, where cattle, sheep, horses and pigs were found, showed that juveniles were present. Among the cattle, for example, there were peaks of slaughtering at 8 months, with lesser peaks at 18 and 30 months, but the high proportion of old females implies that the herd was kept mainly for milk. Sheep showed a similar pattern with most deaths at 8–9 months and 5 years, suggesting that ram hoggets were killed at the optimum time for meat yield while ewes were kept for wool and breeding. Horse was also important to the economy and may have been as numerous as cattle and only a little less common than sheep. Similar high percentages of horses were also noted on flood plain and first-terrace sites at Farmoor and Appleford but not at the mixed farming site of Ashville on the second terrace. The overall impression, therefore, is that the flood plain and first-terrace sites may have been part of a single interdependent system of production where extensive use was made of the special potential of the flood plain pastures for animal husbandry. The flood plains can be shown to have been carefully managed and heavily utilized throughout the Iron Age (Lambrick and Robinson 1979, 56–60).

There are various possible models to explain the differences between the various sites. The simplest would be to suppose that those on the second terrace in some way provided a redistribution function between the animal-rich economies of the flood plain and first terrace and the corn-rich economies of the Cotswold dip slope. This would be consistent with the evidence we have at present but the reality is likely to have been far more complex.

Whatever the overall system, there are likely to have been a number of settlements specializing in the exploitation of their local environments. One such site, dating to the Early Iron Age, has been excavated at Groundwell Farm, Wilts., located on the richer clayey soils south of the Thames valley. Of the bone assemblage recovered, 30–40 per cent was of pig. It is tempting to see this as an isolated community relying heavily upon the products of its own immediate territory which would have been dominated by tracts of woodland providing pannage for the swine.

It is not yet possible to provide a detailed view of economic development throughout the first millennium but several generalizations may tentatively be offered. At present few sites of the Middle–Late Bronze Age are known within the region, but from about the eighth century settlements begin to be established on the gravels. By the Middle Iron Age settlement has become prolific, and it is to this period that the developed system, outlined above, belongs. The gravel tracts are now fully utilized and farms have been established on the Cotswold slopes, though these are more widely spaced. The picture is consistent with the view that considerable population expansion was taking place and all ecological niches were being exploited. That said, there is no evidence of settlement hierarchy at this time.

In the Late Iron Age changes can be discerned. New crops such as bread wheat were being introduced, and it seems that the increased alluviation of the river valleys, probably caused by intensive cultivation of the valley sides, was forcing the abandonment of the flood plains. The emergence of long-distance trade networks may well have been responsible for the creation of large enclosed oppida at Salmonsbury, Abingdon and Dyke Hills, commanding major route nodes.

While the Thames valley has so far produced the fullest evidence for Iron Age economic systems in the Midlands much detail has been added by settlement excavation in Northamptonshire and Bedfordshire. Along the valleys of the Ouse and Nene, settlements appear to be densely scattered much as they are in the Thames valley, but few have been examined. Elsewhere, on the varied soils of the Northamptonshire uplands and the flanking clay lands, a number of large- scale excavations have been carried out. The overall picture is one of settlement expansion in the Middle Iron Age filling up the lighter soils and spreading into the heavy clay land (Knight 1984, 266–83).

Evidence for animal husbandry and cereal growing does not differ significantly from that of other regions of the south. There is support for the view that a greater diversity of crops came into use as the Iron Age proceeded. The animal bone assemblages from several sites, e.g. Twywell, Brigstock and Weekley, show that sheep were the most numerous animal, the percentage rising to 76 per cent at Weekley. The prominence of sheep reflects the potential of the calcareous soils of the uplands. Elsewhere, however, at Moulton Park, Bradwell and Bierton where the resource potentials differ, cattle are the more numerous. Differences of this kind are only to be expected in a region where the geology is so varied.

Field systems are not well represented in the region but droveways and linear ditches divide the landscape. Another boundary feature known as a ‘pit alignment’ is frequently recorded. In the Nene and Ouse valleys 114 pit alignments have been noted, principally as a result of aerial photography (Jackson 1974; Knight 1984, 259–65) and several of these have now been subjected to limited excavation. At Briar Hill Farm the alignment, which was traced for 152 m, consisted of closely spaced sub-rectangular pits averaging 2 m by 1 m and dug to a depth of about 1 m. The pit row had evidently replaced an earlier linear arrangement of small pits or post-holes. The only indication of date consisted of a few sherds of Early Iron Age pottery from the pit fillings. Better dating evidence was obtained at Gretton, Northants, where 114 m of an alignment was carefully examined. Early Iron Age pottery was found in the pits and the filling of one was overlapped by a hoard of currency bars probably dating to the first century BC. There can therefore be no doubt that the pits were of Iron Age date.

While it is clear that pit alignments in some way served to divide land, the physical form of the boundary remains in doubt. It is possible that the spoil was piled between the pits or in a continuous bank along one side, but if this is what was intended it would surely have been more efficient to dig a linear ditch. A more likely explanation, therefore, is that pit alignments were designed to mark the limit of a territory but not to inhibit movement across the line. The phenomenon is particularly interesting and deserves careful attention, not least in the relationship of alignments to other boundary features and to occupation sites.

East Anglia and the Fens

Althouth several surveys of East Anglia and the Fens have been published (Davies 1996; Davies and Williamson 1999; Hall and Coles 1994) comparatively little is known of the food-producing economy of this large tract of countryside. It is, however, clear that the area experienced an expansion of population in the Middle Iron Age, with areas of heavy land coming under cultivation for the first time. The cultivated crops recorded include emmer, spelt, six-row hulled barley and wild or cultivated oats, and the usual range of domesticated animals are present, but samples are too small to allow detailed comparisons to be offered. At Fison Way, Thetford, Norfolk, however, there is evidence that emmer was stored as spikelets along with barley grain. The absence of processing waste at the site suggests that it may have been a ‘consumer site’ supplied with grain from producer farms sited on better agricultural land. One such site was sampled at Staunch Meadow, Brandon, where the assemblages were dominated by weed seeds derived from the cleaning process (Wiltshire and Murphy 1999, 153).

Several fen-edge sites have been examined, most notably Fengate, Haddenham and Wardy Hill, Coveney. All, while producing evidence of the normal domesticates and cultivates, showed a well-developed hunting and collecting strategy making particular use of the fenland environment. At Haddenham the animal assemblage was dominated by sheep, cattle and pig but included beaver and swan in some numbers as well as Dalmatian pelican, crane, heron, mallard, coot and curlew. At Fengate nineteen species of bird were identified together with an extensive range of plants, some of which – opium poppy, celery, mustard, parsnip and thyme – may have been deliberately cultivated. The rich wetland resource will have enabled those controlling it to supplement and to vary their diet to an enviable extent but it is unlikely that these foodstuffs were ‘exported’, though beaver fur, feathers and down may have been produced in surplus for exchange.

The south-west of Britain

While the settlement pattern of south-western Britain is comparatively well understood and the broad outlines of the environmental changes experienced by the moorland massifs can be charted from pollen sequences, very little direct evidence can be brought to bear on the basic questions of crops and herds. The reasons are twofold – flotation has not until recently been used to extract crop-processing debris and the soils are, for the most part, too acid for bones to be preserved.

It is clear, however, that the majority of the settlements relied on a mixed farming regime. Querns and spindle whorls attest to the grinding of grain and to spinning, while stone-walled field systems, largely undated, abound. The provision of outer corrals to a number of the more massively defended settlements (the hill-slope forts or multiple-ditched enclosures) is an indication of the importance of animal husbandry at sites which might be regarded as high status.

At the Cornish multiple-enclosure fort of Killibury, where flotation was carried out, emmer, spelt and oats were identified, while from Goldherring, barley, oats and rye were recovered. In both cases the samples were too small to allow the relative importance of the cereal types to be demonstrated.

A systematically collected assemblage of animal bones from the coastal site of Mount Batten presents a somewhat unusual picture. In the earliest, Late Bronze Age, phase sheep were the most numerous, followed by cattle and then pigs, but the much larger Iron Age group showed that cattle were by now the most important, followed by pig and then sheep. The age at death of the various species implied that while cattle and pig were reared primarily for meat (they were killed as juveniles or young adults), sheep lived until they were mature and were therefore presumably kept to provide wool (Grant 1988). This pattern is in marked contrast to the normal husbandry pattern of the south, where meat production was a secondary consideration. It is difficult to assess the Mount Batten evidence since there is nothing with which to compare it locally. While it could be typical of a south-western regime it is more likely either that the site was of high status or that meat was being processed for export.

A further insight into the localized nature of the south-western economies is provided by a series of rescue excavations in east Devon along the line of the A30 between Honiton and Exeter (Fitzpatrick et al. 1999). Here the agricultural region was dependent upon a variety of crops including emmer, spelt, bread wheat, barley, celtic beans, peas and flax. The persistence of emmer is in contrast to the cropping pattern in Wessex, where, by this time, spelt had replaced emmer. A study of the processing waste suggests that crops were harvested by cutting low down with a sickle and also by uprooting, and the harvest was stored in sheaves or as threshed and winnowed grain with minimal processing. Sieving and cleaning took place as and when the grain was needed for consumption. The overall impression given by this evidence is of production at household level with little sign of complex patterns of organized redistribution.

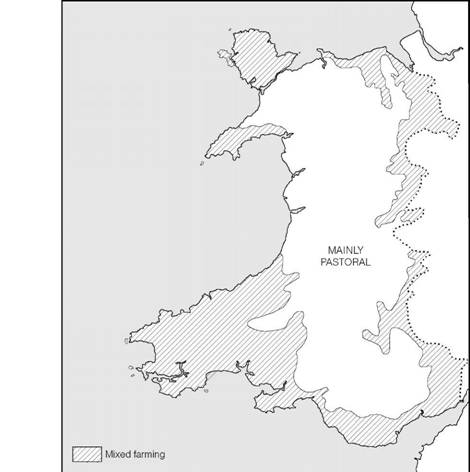

A totally different pattern of subsistence is evident from the rich remains recovered from the excavation of the ‘lake villages’ of Glastonbury and Meare, both of which commanded a very wide variety of rich resources including large tracts of wetlands. The crops grown on the drier lands around included wheat, barley, oats and celtic beans and peas, while animal husbandry was dominated by sheep, with smaller herds of cattle and some pig rearing. In addition to these Iron Age staples wild fowl and fish were to be had in plenty. At Glastonbury over thirty species of birds were identified, including mallard, teal, widgeon, tufted duck, coot, moorhen, crane, heron, partridge and grouse, while at Meare bones of eel, salmon, roach, cod and bass have been found. Other wild animals such as red and roe deer and wild boar were hunted for food, while otter, beaver, fox, wild cat, weasel, marten and polecat provided furs. The richness of the assemblage is in part the result of the unusually varied environment, but it is a reminder of the very extensive use which Iron Age communities would have made of the varied natural resources of their territories. Those able to exploit the wetlands of Somerset would have been able to acquire resources, like furs, which would have been of special value in the networks of exchange with communities on the drier chalklands to the east.