3

Background

As a prelude to our consideration of the Iron Age communities of Britain, beginning in the eighth century BC, it is necessary to set the scene in this brief introductory chapter if only to establish the trajectories – economic, social and political – evident among the developing indigenous communities.

In Europe the period from the thirteenth century BC until the eighth century is conventionally referred to as the Late Bronze Age. The same term is still used in Britain but it is more usual now to divide the period into five separate phases based on the typology of bronze weapon assemblages named after individual type sites (Figure 2.2). During this Late Bronze Age period the pottery used throughout much of the country was predominantly plain and the forms of the bowls and jars were simple. In the preceding period of the Middle Bronze Age, in the south and east of Britain, the pottery had been more elaborate and often incorporated decorated wares. These assemblages are referred to as Deverel–Rimbury. The change from Middle Bronze Age (Deverel–Rimbury tradition) to Late Bronze Age (Plain ware tradition) some time in the first half of the thirteenth century BC signifies the beginning of a series of changes. Taking a broad perspective it could be argued that the Late Bronze Age in Britain was a period of transition from the early prehistoric cycle of the Neolithic to Middle Bronze Age to the late prehistoric/early historic cycle which came to an end with the collapse of the Roman political system in the fifth century AD.

Climatic change

The Late Bronze Age spanned a period of climatic change which impacted on the different regions of Britain in different ways.

The first half of the first millennium BC was a period of climatic deterioration, during which the comparatively warm dry conditions of the Sub-Boreal period gave way to a cooler, wetter phase, conventionally known as the Sub-Atlantic period. In sequences constructed from bog profiles, this phase of relatively rapid change can usually be recognized from a study of the pollen content and the macro plant remains. So clear was this change in many exposures in Europe that it became known as the Grenzhorizont, or ‘boundary horizon’. In terms of the British pollen sequence it marks the boundary between Zone VIIb and Zone VIII (Pennington 1974, 79–88).

There has been much discussion about the date and duration of the Grenzhorizont (summarized in Piggott 1973), but Godwin’s work on the prehistoric trackways in the Somerset Levels has clarified the situation (Godwin 1960; Coles 1972). Here, as the raised sphagnum bog of the preceding period began to be flooded with calcareous ground water, presumably caused by increased rainfall, the local communities responded by building trackways of timber and brushwood across the surface of the bog to maintain easy contact between the higher, settled areas. A number of these trackways have now been subjected to radiocarbon dating, providing a consistent range of assessments between 1000 and 500 BC, representing the maximum duration of the Zone VIIb–VIII transition. Confirmatory dates in the eighth century have been obtained from Tregaron in Wales and Flanders Moss in Scotland.

It is difficult at this stage to assess the significance of a relatively rapid period of climatic deterioration on settlement pattern and economy, but it is evident that upland areas in the north and west would have become unsuitable for permanent habitation as areas of blanket bog began to form, while increased rainfall particularly in the west would have rendered certain kinds of cereal growing more hazardous. In the period of climatic optimum, roughly 1250–1000 BC, cultivation of the northern uplands reached 400 m but as conditions deteriorated in the next few centuries, giving rise to a cold and stormy period, the mean temperature fell by nearly 2°C, reducing the growing season by about five weeks (Lamb 1981, 55). For the upland settlements this would have spelt disaster, drastically reducing the maximum altitude at which successful cultivation was feasible to about 250 m. Such a rapid change cannot have failed to have a dislocating effect on society. It is perhaps in causes of this kind that explanations for the apparent retardation of cultural development in parts of the west and north of Britain should be sought. It was in the south and east, where the effects of climatic change were slight, that the major economic, technical and social developments took place.

Settlement in the Thames valley

The Thames valley has long been known for the considerable array of bronze tools and weapons recovered from the region, many of them coming from the river itself as the result of dredging operations. But it is only in the last thirty years or so that the complexity of the Late Bronze Age settlement pattern has begun to become apparent.

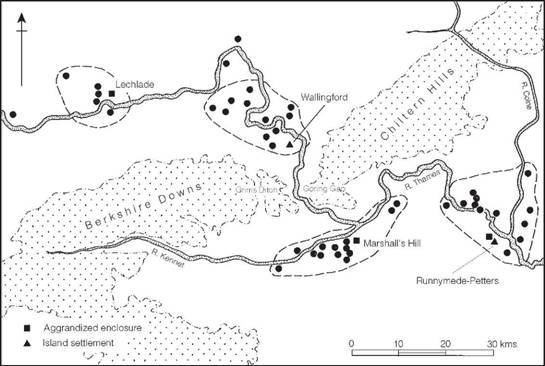

Already, in the Middle Bronze Age, large areas of the valley had been transformed by the imposition of new land divisions, many of them fitting into earlier landscapes dominated by funerary monuments giving the impression that old ancestral markers were being respected and revered while the landscape was being colonized for a more ordered and permanent agro- pastoral use. This development appears to have intensified during the Late Bronze Age with more settlements being established and great areas of land brought under control. A recent survey (Yates 1999) has identified forty-four known farming sites in the valley of the Thames and Kennet upriver from the Colne valley and there can be little doubt that many hundreds more must have existed. Within this broad scatter of farmsteads a few sites stand out by virtue of their enclosing earthworks or island locations as places of greater significance. Yates (ibid.) has identified four of these, from the presently available evidence, which, he suggests, may have been focal centres of regional importance, each in some way ‘controlling’ a group of communities living in the neighbouring farmsteads (Figure 3.1). Distributions of metalwork and styles of pottery add some support to the view that these groupings may have been socially distinct polities.

Figure 3.1 Late Bronze Age settlement in the Middle and Upper Thames valley (source: Yates 1999).

Of the centres of regional importance the best known is the riverside settlement found at Runnymede Bridge, Egham, close to the confluence of the Thames and the Come Brook. Here the complex piling of the river bank over a distance of more than 35 m implies a considerable expenditure of effort in the interests of providing landing facilities. The associated assemblage is particularly rich, including a range of bronze tools, implements and ornaments of Late Bronze Age type, together with ample evidence of metalworking. In addition there was a variety of bone and antler tools, clay spindle whorls and loom weights and exotic imports including shale armlets and amber beads. The richness of the assemblage may, at least in part, be due to the high status and (or) trading nature of the settlement. Its extent is undefined but traces of contemporary occupation have been found at various points up to 400 m from the river, suggesting a complex of considerable size. The discovery of the Runnymede settlement is a reminder of the importance of the Thames as a route of communication.

Upriver from Runnymede other centres have been identified at Marshall’s Hill, Wallingford and Lechlade, while downriver similar riverside settlements may well exist at intervals along its length, as for example at Syon Reach, Brentford where a suggestive range of bronzes and timber piles were recorded early last century.

In addition to these high-status riverside settlements others of a more normal agricultural kind have been excavated on the terraces of the Middle and Upper Thames valley and its tributary the Kennet. At Aldermaston an extensive spread of pits and post-holes was uncovered, representing part of a settlement of unknown extent. Radiocarbon dates of 1690–1390, 1319–1214 and 977–899 Cal BC are rather unhelpful for a site thought to be of short duration but might indicate occupation centring on the twelfth century BC. Eight kilometres away, at Knights Farm, another scatter of pits and post-holes was partly explored. Radiocarbon dates range from 1610–1390 Cal BC, associated with typologically early pottery, to a group of dates for the latest phase which together suggest occupation spanning the period from the fifteenth to the seventh centuries BC.

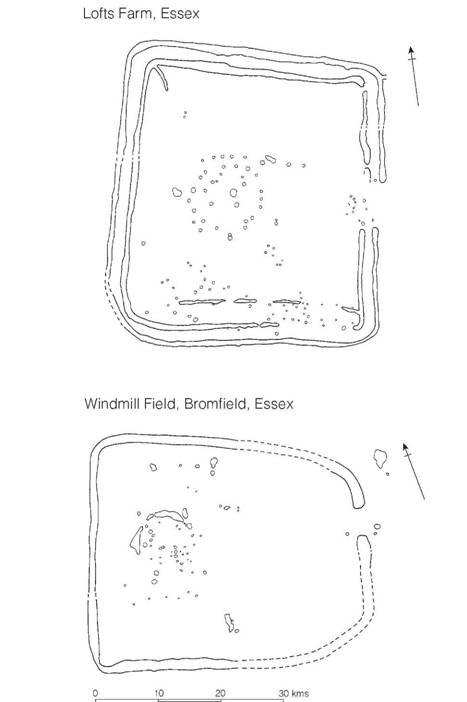

Figure 3.2 Late Bronze Age settlements in Essex, Lofts Farm (source: Brown 1988) and Windmill Field, Bromfield (source: Atkinson 1995).

These two Kennet valley sites are of interest both in providing useful ceramic assemblages and in offering some hint of the complexities of the economic system. At Aldermaston large quantities of cereal grain were found, presumably reflecting the production of the surrounding land, while at Knights Farm, around which was a high percentage of seasonally waterlogged land, there appears to have been a greater emphasis on livestock. Loom weights, however, were common on both sites. The actual percentages of the cereals recovered from Aldermaston were similar to those from the southern chalkland sites, with the wheat/barley ratio varying from 7.7 per cent/92.3 per cent to 18 per cent/82 per cent depending on context. Of the barley, between 63 and 92 per cent was hulled compared with the naked variety but the absence of processing debris on the site may suggest that the crop was brought in from elsewhere. A different aspect of the economy is presented by the settlement at Reading Business Park. Here textile production appears to have been organized on an extensive scale resulting in rows of flax retting pits.

By the Late Bronze Age most of the Thames valley settlements were surrounded by field systems defined by ditches and presumably hedges, served by extensive systems of trackways and provided with water-holes convenient for livestock. Reviewing the evidence overall, stock rearing seems to have been an important part of the food-producing regime and by the Late Bronze Age it would seem that pastoralism had become the dominant mode of production.

In his review of the settlement evidence from the Middle and Upper Thames valley Yates (1999, 167–8) argues that there was a social and economic dislocation at the end of the Late Bronze Age, with many sites showing signs of abandonment, though settlements in the extreme upper reaches of the river at Shorncote and Lechlade appear to have continued without a break. Evidence from the Lower Thames valley, most convincingly at Hornchurch, presents a similar picture of dislocation and abandonment. We shall return later to the potential significance of these issues.

In Essex recent excavations have begun to define a distinctive settlement type characterized by a single circular house set within a rectangular ditched enclosure. Clear examples of the type are known from Lofts Farm and from Bromfield (Figure 3.2). How widespread such a settlement form was it is impossible yet to say, nor is it clear what the social difference was between these enclosures and the more substantial ring forts to be described below. It is now clear, however, that a considerable variety of settlement type is beginning to appear in the east of Britain.

Settlement in East Anglia

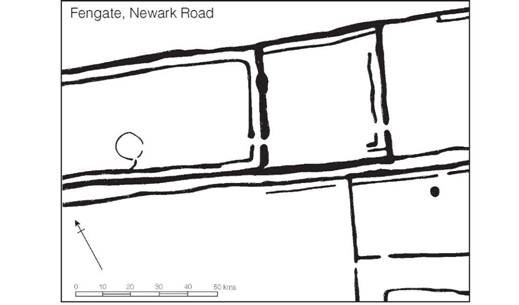

While the evidence from Late Bronze Age settlement in East Anglia is not particularly extensive, detailed work on the edge of the Cambridgeshire Fens at Fengate has produced a comprehensive picture of settlement and land use throughout the Middle and Late Bronze Age. The principal structures to survive are systems of regularly laid out fields and paddocks bounded by ditches and associated with ditched trackways. Within this framework the settlement focus seemed to shift over time. The explanation favoured by Pryor (1975, 336–7; 1992) is that the fields represent the winter pasture for flocks and herds, which would have spent the summers roaming free on the rich grass of the adjacent fen islands. The regularity of the layout of the fields implies a strict order of the kind one would expect if the scarce resources of winter pasture were to have been fairly apportioned between the rival claims of a large and well-established community. In such a system the grain necessary for the community is likely to have been grown on the drier upland areas and exchanged with the fen-edge communities.

Figure 3.3 Late Bronze Age paddocks at Newark Road, Fengate, Peterborough (source: Pryor 1996).

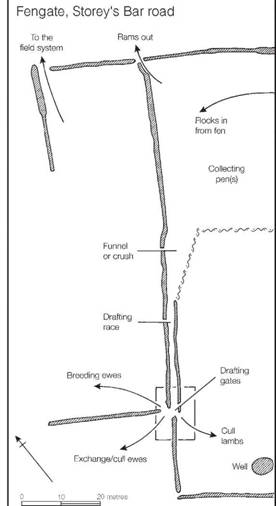

Within the system of enclosures examined at Fengate, Pryor (1996) has convincingly shown there to have been carefully planned stockyards designed for livestock management which probably served the larger community. Here animals would have been gathered for culling and exchange on fixed occasions during the year when those attending would have engaged in the social intercourse necessary to maintain harmony among dispersed communities. The archaeological detail is such that the processes of animal handling can be suggested in impressive detail (Figures 3.3 and 3.4). On analogy with modern sheep handling it is estimated that the pens at Newark Road could have accommodated 3,400 sheep while the collecting yard at Storey’s Bar Road would have held 2,500 animals. That the complex communal facilities at Fengate are by no means unique is suggested by the discovery of other complexes of fields, pens and droveways at Block Fen and at West Deeping, Lincs. (Pryor 1996, 321).

Figure 3.4 Suggested interpretation of the Late Bronze Age ditch system at Storey’s Bar Road, Fengate, Peterborough (source: Pryor 1996).

Ring forts in eastern England

Throughout much of eastern England, including the Thames valley, the Middle and Late Bronze Age settlements are largely unenclosed, the circular houses in which people lived being scattered, often over a considerable area, and rebuilt with considerable rapidity usually on or close to the same plot. This is particularly well demonstrated by the excavations at Reading Business Park where, in one part of the settlement, within the 3,500 sq m examined, at least twenty houses were identified.

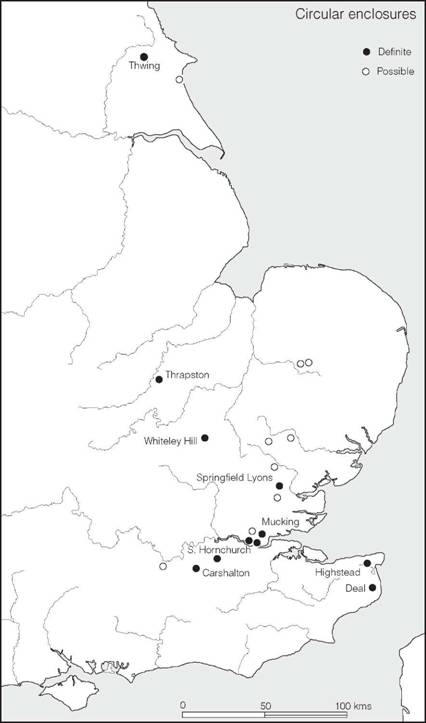

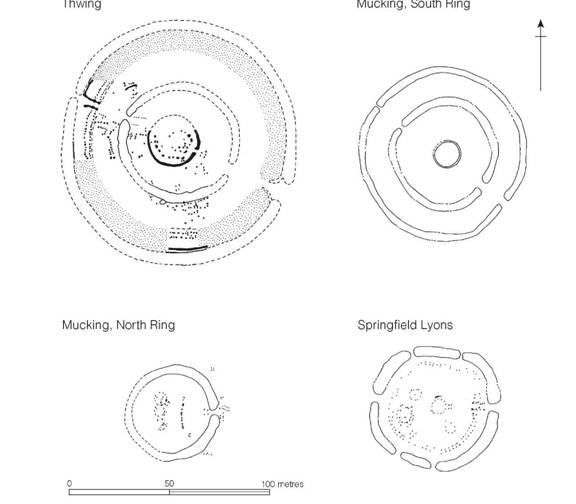

More rarely, within the east of the country, settlements comprising one or several contemporary houses have been found, surrounded by substantial ring ditches (Figure 3.5). These ‘ring forts’ as they have come to be known (Needham 1992) vary in size and defensive complexity. Three extensively excavated examples, Mucking (Essex), Springfield Lyons (Essex) and Thwing (Yorks.) serve to demonstrate the range within the general category.

Figure 3.5 Distribution of circular defended enclosures of the early first millennium BC (sources: various)

At Mucking (Figure 3.6) two ditched enclosures of broadly similar date were discovered and largely excavated. They had been superimposed on a second-millennium field system. The South Ring consisted of a double ditched enclosure of circular plan, with opposed entrances, measuring 83 m in diameter overall, with a circular building 13 m in diameter placed in the centre of the inner enclosure. The North Ring was smaller, some 48 m in diameter, and contained three circular post-built houses and a substantial fence shielding them from one of the entrances. The ditch had been recut on one occasion. Radiocarbon dates were obtained from both sites: for the South Ring: 1050–820, 1052–896 and 1051–889 Cal BC; and from the North Ring: 930–760 and 932–799 Cal BC. Since the samples for the North Ring were taken from the recut ditch the initial dates of both sites are likely to have been much the same, somewhere in the tenth to eighth centuries BC.

The enclosure at Thwing, though similar in many respects to Mucking South Ring, was conceived on a grander scale (Figure 3.6). It comprised two concentric ditches with opposed entrances, the outer ditch enclosing an area of 105 m diameter. Immediately inside the outer ditch was a rampart of chalk rubble fronted by a palisade of timbers set in a continuous bedding trench. The rear face of the bank was given stability by two rows of timber presumably laced together to form a box-like structure. The inner ditch had no rampart. Inside was a circular timber building 25 m in diameter with an inner setting of posts on a 16 m diameter. A radiocarbon date of 1134–1006 Cal BC was obtained for an unweathered occupation layer immediately beneath the rampart.

Springfield Lyons was more complex (Figure 3.6). The ditch, roughly circular in plan and 54 m in diameter internally, was discontinuous, with the main entrance lying to the east. Immediately inside the ditch was a 6 m gap where the rampart may have stood. This was backed by a double circle of post-holes interpreted as an inner revetment and walkway. Within these enclosing structures the remains of three circular post-built houses were discovered, one of which was centrally placed and faced the entrance. Radiocarbon dates of 1520–1210 and 1020–760 Cal BC for charcoal from the enclosure ditch and 1055–902 Cal BC for charcoal from a post of the central house suggest a possible date range in the tenth or ninth century.

The Mucking, Springfield Lyons and Thwing enclosures were built on a monumental scale. At Thwing the associated assemblage included spindle whorls, loom weights, querns and a range of pottery appropriate to a domestic site, but some objects of status were recovered including beads, pendants and bracelets of jet together with a range of decorated bronze pins, rings and a fragment of a spearhead. The Mucking Rings also produced normal domestic assemblages, the South Ring yielding in addition a bronze pin and a fragment of a copper ingot, while the North Ring produced a fragment of a socketed axe. The assemblage from Springfield Lyons was more limited but included spindle whorls and loom weights together with debris from bronze casting. The available evidence would suggest therefore that the enclosures were domestic sites but the monumentality of the architecture and exotic artefacts imply an unusually high status.

Something of the contexts of these ring forts is shown by excavation of an extensive Late Bronze Age landscape on a gravel terrace in the Lower Thames valley at Hornchurch (Essex). Here a ring ditch protecting a single circular house was associated with a droveway and a system of ditched fields together with a scatter of houses and areas of intensive occupation. In this example the ring fort, droveway and fields all appear to be broadly contemporary.

Several other sites, less extensively excavated, appear to belong to the same general type. At Mill Hill, near Deal in Kent, a circular enclosure 50 m in diameter was discovered, producing, among other things, a range of bronze and shale items. A similar, but somewhat larger site was located at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Carshalton, Surrey: others are also known (Figure 3.5). The predominantly easterly distribution may be fortuitous, but the circular ditched enclosures are unknown in the well-studied area of Wessex and they may therefore reflect a particular social manifestation restricted to the eastern region in the first two or three centuries of the first millennium.

Figure 3.6 Circular defended enclosures of the early first millennium (sources: Thwing, Manby 1980; Mucking, Jones and Bond 1980; Springfield Lyons, Buckley and Hedges 1987).

Settlements on the southern British chalkland

Settlements of the Middle and Late Bronze Age (c. 1500–700 BC) are reasonably well known on the chalklands of southern Britain, where more than forty individual sites have been recorded and at least half of these subjected to excavation of differing thoroughness. One of the characteristics of the chalkland settlements, in contrast to those of the Thames valley and East Anglia, is that from the Middle Bronze Age onwards they were generally enclosed by a fixed boundary. This move to enclosure at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age is thought to have resulted from changes in kinship and landholding practices (Thomas 1997).

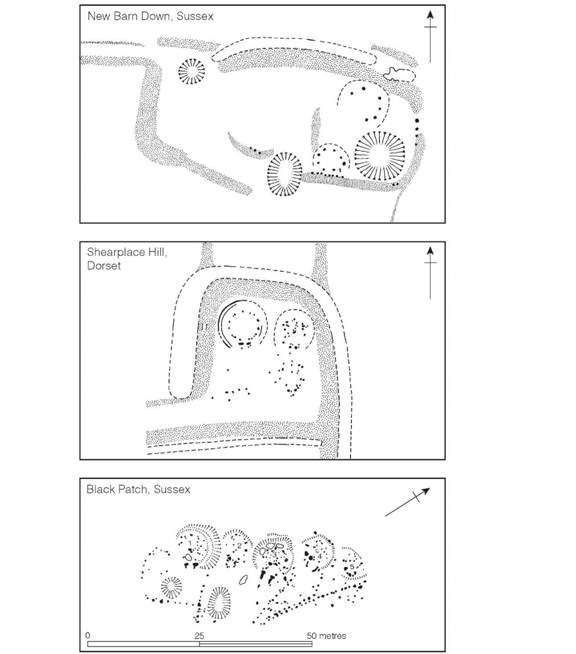

Throughout the entire chalkland zone the basic structural unit appears to have been enclosure, frequently of sub-rectangular form, defined in various ways by combinations of banks, ditches and palisades. At Shearplace Hill, Dorset (Figure 3.7), the settlement area is enclosed by a U-shaped ditch some 3 m wide, with an internal bank in which may once have been bedded a palisade or perhaps a thorn hedge. At Cock Hill, Sussex, on the other hand, the bank and palisade are external to a 2 m wide ditch. Another variant appears at New Barn Down, Sussex (Figure 3.7), and at Thorny Down, Wilts., where one side only is ditched, the other three being defined by banks, which at New Barn Down supported a close-set palisade. In all these examples, internal settings of posts show that the earthworks enclosed circular huts, usually 6.0–7.5 m in diameter. There were at least two at New Barn Down, two or three at Shearplace Hill, five or more at Cock Hill and probably as many as nine at Thorny Down. Not all, of course, need have been in use at one time, since replacement and rebuilding were probably carried out periodically. The plan is clear at Shearplace Hill, however, where two definite houses and a possible third, enclosing a working area, seem to constitute a single contemporary unit, which would have been ideally suited to a social group of family or extended family size. The unenclosed settlement at Chalton, Hants, was of similar size, with one large hut, a smaller hut with a central hearth for cooking and two unroofed working areas. Here a tentative assessment of grain production, based on the capacities of the storage pits, supported the idea of a single family unit and indicated a total arable in the order of 6.5 ha.

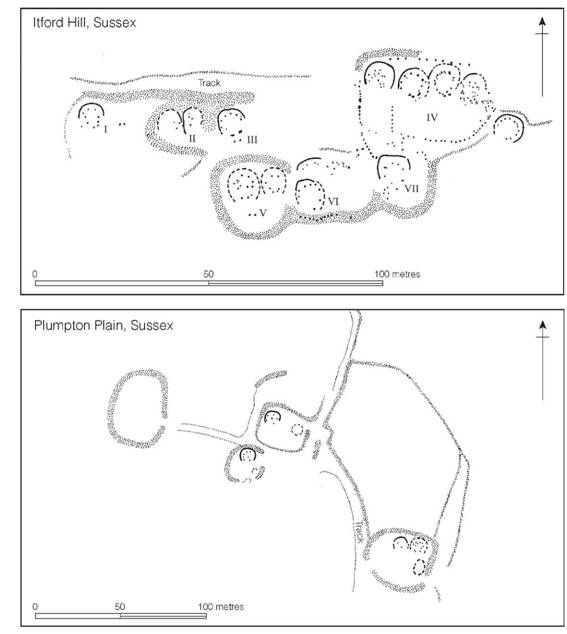

While single-enclosure habitations of the types mentioned above are relatively common on the chalklands a few sites present the appearance of nucleation, but here we face the problem of how many of the individual structural elements were strictly contemporary. The possibility remains that the overall pattern was caused by the gradual shift in location of a single enclosure representing a family unit within a defined and limited territory. Three Sussex sites, Plumpton Plain A, Itford Hill and Black Patch exemplify the problem. Plumpton Plain A (Figure 3.8) consists of four sub-rectangular enclosures defined by banks, spread out along a street over a distance of about 213 m. Three of them have been partially excavated and each has proved to contain at least one hut. While the plan could represent a contemporary situation, the agglomeration thus forming a hamlet or small village, it is equally possible that the enclosures were successive.

At Black Patch on the other hand a series of hut terraces were found scattered among contemporary fields over a distance of about a kilometre. One of these (hut platform 4), selected for total excavation, revealed five individual circular houses set in fenced enclosures containing two ponds (Figure 3.7). The plan suggests broad contemporaneity, with an occupation span not exceeding thirty to fifty years. A detailed analysis of the artefacts found on the floors of the individual buildings led the excavators to believe that hut 1 was used largely for food production and hut 3 for craftwork and storage, while hut 4 combined elements of both. In huts 2 and 4 little evidence of function survived. Taking the evidence of plan and activity together it is tempting to see the community as an interdependent unit, quite possibly an extended family. The question still remains, how did this hut complex relate to the other three within the immediate vicinity? Are we dealing with a single extended family moving every generation or two or several such groups? The resolution of the problem is beyond the present scope of the evidence.

Figure 3.7 Settlements in southern Britain, second to first millennium (sources: New Barn Down, E.C. Curwen 1934a; Shearplace Hill, Rahtz and AρSimon 1962; Black Patch, Drewett 1982).

Figure 3.8 Settlements in southern Britain, second to first millennium (sources: Itford Hill, Burstow and Holleyman 1957; Plumpton Plain, Holleyman and Curwen 1935).

The third Sussex example, Itford Hill, superficially presents a dense form of nucleation (Figure 3.8). Here a complex of six enclosures lay adjacent to each other in an elongated area some 128 by 46 m. Extensive excavation, under modern conditions, has allowed much of the plan to be recovered, displaying distinctions in both size of house and function. A reassessment of the published evidence (Ellison 1978, 36) has suggested that the complex is divisible into four distinct structural phases, the first comprising enclosures I, II and III, the second enclosures IV and VIII, the third enclosures V, VI and VII, and the fourth enclosure IX. The successive units were broadly similar in size and function and comparable to Black Patch hut platform 4 which, we have suggested, probably represented the homestead of an extended family. Additional support for this view comes from the cremation cemetery close to Itford which can be shown, by joining potsherds, to have been closely related to the settlement. The age and sex pattern of those buried here is similar to that which would be expected of a single family unit using the burial ground over several generations. Thus the Itford evidence shows that even on apparently nucleated sites the basic settlement unit need be no larger than the extended family. Nowhere on the chalklands of southern Britain is there convincing evidence of any larger settlement agglomeration.

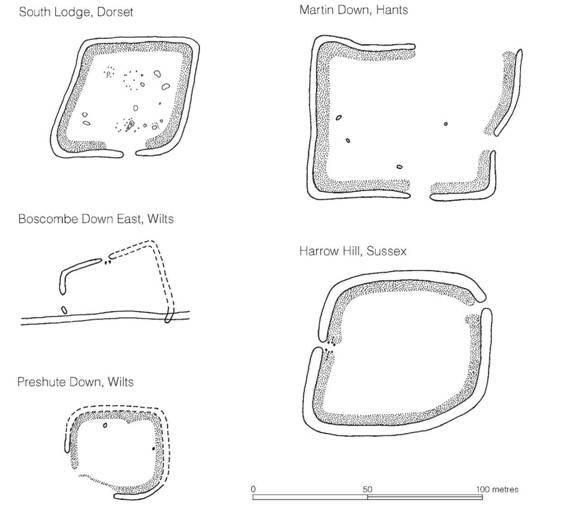

A second type of enclosure exists in the same general area as the enclosed settlements, and belongs to a broadly similar period. These enclosures (Figure 3.9), invariably ditched with a bank on the inner side, differ from the settlements in that they yield little evidence of intensive habitation. The two well-known examples, South Lodge Camp and Martin Down Camp, excavated by Pitt Rivers in Cranborne Chase, are both strongly rectilinear in form; South Lodge Camp possesses a single entrance while Martin Down has two entrances and an apparently undefended length along the north side which may originally have been closed with hurdles or some temporary structure leaving no archaeological trace. Pitt Rivers’ excavations suggested that the interiors were largely devoid of internal features, apart from a few undated pits, but the re-excavation of South Lodge Camp presents a more complex picture and, incidentally, highlights how much Pitt Rivers missed. It is now clear that the enclosure was constructed within an existing field system. Inside were two circular houses, the larger measuring 8 m in diameter, together with several small pits and isolated post-holes. In view of this new evidence the pits found in the Martin Down enclosure may be seen as the only element Pitt Rivers recognized of a more extensive settlement. Less certainty attaches to the contemporary Wiltshire enclosures on Boscombe Down East, Preshute Down and Ogbourne Down. At Boscombe Down East only limited excavation was undertaken, but sufficient to show that the enclosed 0.1 ha was largely without occupation, although a scatter of pottery was found outside. The ditch clearly related to a linear ‘ranch boundary’ of the type to be described later (pp. 421–2), which formed its southern side. The northern entrance was provided with a pair of double (recut?) post-holes, presumably defining the position of a gate, a little over 1 m wide, set back to be on line with the inner bank. This suggests that the bank may have formed a bedding for a continuous palisade, the holes for which did not penetrate the solid chalk. The same may well have been the case with the South Lodge Camp and Martin Down Camp enclosures, but the possibility is not susceptible of proof. The enclosures on Preshute Down and Ogbourne Down in north Wiltshire are even less well known, but they do not differ significantly from those just described.

The exact status of the rectangular ditched enclosures of Wessex is difficult to define with so little reliable evidence available. While they could represent simply a variant of the extended family unit discussed above, the act of deliberate enclosure by labour-intensive ditch digging, the comparatively large house at South Lodge and the number of storage pits at South Lodge and Martin Down and Preshute, may be indicative of settlements of higher status.

Figure 3.9 Ditched enclosures in southern Britain, second to first millennium (sources: South Lodge, Pitt Rivers 1898, Barrett, Bradley, Bowden and Mead 1983; Martin Down, Pitt Rivers 1898; Boscombe Down East, Stone 1936; Preshute Down, C.M. Piggott 1942; Harrow Hill, Holleyman 1937).

Before considering the economic pattern to which these settlements and enclosures belong, something must be said of their date. Radiocarbon dates are available for Shearplace Hill, 1180 ± 180 BC; Chalton 1531–1411; Itford Hill 1182–1128; Black Patch, four dates between 1393–1213 and 1016–888 Cal BC; and South Lodge 1520–1260, 1640–1410 and 1200–970 Cal BC. Although too much reliance should not be placed on such a disparate collection of dates, amassed in a somewhat ad hoc manner, the overall impression given is that the majority of these sites lay within the period 1500–1000 BC and were therefore traditionally Middle Bronze Age passing into the beginning of the Late Bronze Age. This is entirely consistent with the few bronzes which have been found stratified in settlement contexts. The dearth of dates in the ninth and eighth centuries is not particularly significant given so small a sample. At Plumpton Plain an analysis of the surfaces of the whetstones suggested the sharpening of iron tools which, if true, can hardly allow the site to be dated much before the eighth century. Similarly, at Boscombe Down East what was claimed to be iron slag was found in the primary silt of the ditch.

Besides pottery, the surviving material culture of these Middle to Late Bronze Age settlements is sparse. Awls and needles of bone and scrapers of flint point to leather-working on a large scale. Cylindrical loom weights of clay, clay spindle whorls and a single example of a bone weaving comb from Shearplace Hill together with a set of loom weights from Black Patch show that wool was being spun and woven, and numbers of fragmentary querns of saddle type underline the significance of grain production to the economy. Bronze tools and weapons are relatively rare, no doubt because of their value, but awls were found at Black Patch, Chalton, Martin Down and South Lodge Camp; socketed spears occur at Thorny Down, South Lodge and New Barn Down; knives of various kinds are known from Chalton, New Barn Down, Black Patch and Plumpton Plain, where a ferrule and a fragment of winged axe were also found. The early settlement at Chalton produced a palstave. Razors from Black Patch, South Lodge Camp and Martin Down Camp, ribbed bracelets from Thorny Down and South Lodge Camp and a conical bronze mounting from Chalton show that bronze was also used for less utilitarian purposes. While it is fair to suppose that many of the above types could have been current after 1000 BC, the palstave, conical mounting and ribbed bracelets all derive ultimately from the ‘ornament horizon’ of the thirteenth to twelfth centuries BC and must indicate a second-millennium origin for the sites on which they occur. In contrast, the winged axe and socketed knife from Plumpton Plain and the collection of objects from Highdown Hill, near Worthing, are firmly in the Late Bronze Age tradition of metalwork, dating perhaps to as late as the eighth or seventh century.

The economy of the chalkland settlement

The presence of saddle querns and grain storage pits on many of the settlement sites (both cultural traits can be traced back into the Neolithic period) emphasizes the fact that the basis of the subsistence economy was corn growing. Analysis of carbonized grains and grain impressions on pottery provides a general picture of Late Bronze Age grain production, with barley predominating – amounting to about 80 per cent of the total output compared to emmer wheat. Of the total barley crop some 70 per cent was of the hulled variety – a type suitable for winter sowing. A large quantity of carbonized grain found in one of the pits at Itford Hill proved to be almost entirely of hulled barley of both the nodding bere variety (Hordeum tetrastichum) and the erect form (Hordeum hexastichum); only five grains of emmer wheat were recorded in the entire sample, but careful analysis allowed the seeds of fourteen different weeds of cultivation to be isolated, including false cleavers, barren brome, black bindweed, opium poppy and many others.

Systematic sampling at Black Patch has produced a detailed picture of crop growing on the downs of eastern Sussex. Of the contexts sampled, hulled barley occurred in 88 per cent, emmer in 47 per cent and spelt in 18 per cent. The total absence of naked barley is surprising. In addition 6 per cent of the contexts also produced beans (Vicia faba) which was to become of far greater importance to the later Iron Age economy. These figures for the Middle to Late Bronze Age must be seen against a gradually increasing amount of hulled barley at the expense of naked, and of wheat gaining in importance over both types of barley, as improved farming methods, including a greater reliance on winter-sown crops, gradually came into use towards the beginning of the first millennium (Burgess 1985, 203–4).

Several of the settlements referred to in the foregoing pages are intimately connected with field systems defined by banks – known as lynchets – created largely as the result of ploughing on a slope, a process which allows soil to accumulate at the lower boundaries of the ploughed area. These banks were often increased in height by flints and rubble picked off the fields during cultivation. Since the light ard available at the time would only have broken the soil and not turned a furrow, as in the case of a plough provided with a mould-board, it is generally assumed that each field was ploughed in two directions to break the soil sufficiently for sowing. Archaeological traces of cross-ploughing are well attested in Bronze Age contexts in this country and abroad. Such a treatment would result in a patchwork of small, squarish fields, many hundreds of hectares of which are known. It is often very difficult to distinguish between fields of Bronze Age, Iron Age or Roman date, but one of the Ogbourne Down enclosures evidently post-dates the initial use of a group of fields and the same is true at South Lodge, while at Itford Hill, New Barn Down, Martin Down Camp and Plumpton Plain A, the trackways leading to the settlements are closely related to field systems, which may therefore be contemporary.

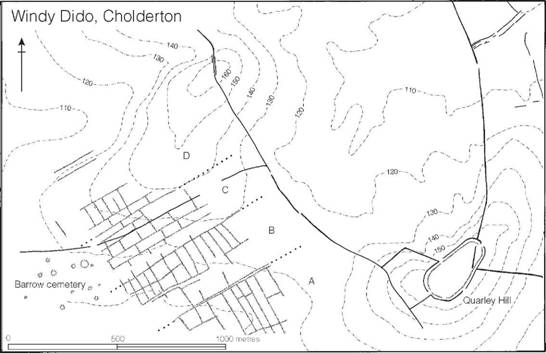

In several parts of Wessex there is clear evidence to suggest that large areas of land were laid out in cohesive tracts of fields as part of a single planning operation (Cunliffe 2000, 155–60). Such systems show a strict regularity and are generally referred to as coaxial systems. In many instances these systems can be shown to have been laid out in the Middle Bronze Age. A good example is provided by the complex at Windy Dido (Hants) (Figure 3.10) where some 90 ha of a gentle east-facing slope were divided into fields arranged in five blocks of roughly equal size extending from a linear ditched boundary running along the crest of the hill to an earlier barrow cemetery occupying lower ground to the west. The division of the fields into five units suggests the possibility that each block may have been the preserve of a single lineage. Another large block of coaxial fields at Fiveways/New Buildings, just to the west of Danebury, was laid out from an existing prominent barrow and was immediately adjacent to two rectangular ditched enclosures which fronted on to a road leading from the field system to the valley of the River Test. A third field system occupied the slope immediately to the east of the later hillfort of Woolbury. Here the blocks of fields seem to have been delineated by boundary ditches. All three examples are redolent of careful planning under some coercive authority.

While the preparation of crops must have accounted for much of the communities’ efforts, the tending of flocks and herds can have been of no less importance. Each of the excavated occupation sites has produced evidence of oxen, sheep and goats, with lesser numbers of pigs, horses, dogs and deer usually present. Where samples are large enough, and adequate quantitative records have been kept, as at Black Patch, Martin Down Camp and South Lodge Camp, oxen are found to predominate.

The existence of extensive areas of arable fields from the Middle Bronze Age implies that crop growing played an important part in the economy, but the subsistence farming of the region must have involved a close interreliance between arable and pastoral activities, with the animals used to manure the fields while gleaning from the stubble after the harvest. During the growing seasons the flocks and herds would have been turned loose on the open downland or in the woods to forage for themselves.

Figure 3.10 Blocks of coaxial field systems lying between a barrow cemetery and a linear ditch at Windy Dido, Hants (source: Cunliffe and Poole 2000g).

During the Late Bronze Age there seems to have been a major reorientation of the subsistence economy, with a decline in the importance of crop growing and a rise in the importance of animal husbandry. The evidence for this is the appearance of extensive systems of linear ditches, often running for many kilometres across the countryside, cutting indiscriminately through existing field systems. While these ‘ranch boundaries’, as they are sometimes called, can be shown to put some earlier fields out of operation they do not necessarily imply the wholesale abandonment of agriculture. These fascinating issues will be considered in more detail in a later chapter (p. 421).

Hill-top enclosures in southern Britain

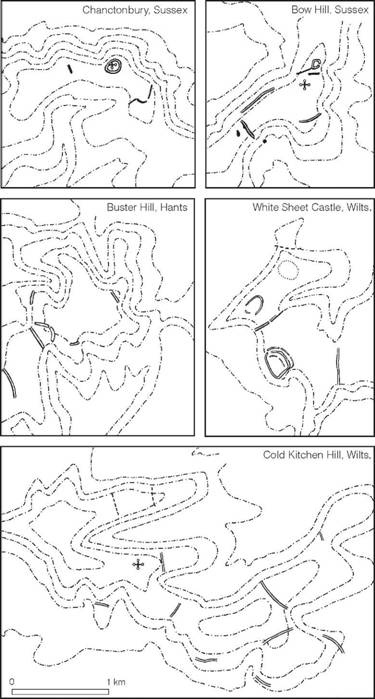

It will be shown in chapter 15 that the construction of hillforts had begun by or soon after 800 BC, but the tradition of building enclosures on hill-tops and of partially enclosing large areas of upland by means of lengths of earthworks can be traced back well into the second millennium. Here we must briefly examine selected sites belonging to these two early categories.

Hill-top enclosures are best exemplified by two sites: Harrow Hill, Sussex, and Ram’s Hill, Berks. At Harrow Hill a sub-rectangular enclosure was defined by a ditch and a shallow bank into which had been set a close-spaced palisade of timbers, the holes for which had penetrated the natural chalk (Figure 3.9). Of the two entrance gaps evident, one was excavated, exposing an entrance passage flanked by two pairs of timbers 2 m apart. Excavation was limited and finds were few, but pottery evidence would hint at an early first-millennium date. More remarkable was the collection of animal bones which included the remains of between fifty and a hundred cows’ skulls with hardly a trace of a limb bone. If this density proved to be even throughout the enclosure it is estimated that more than 1,000 animals would be represented. Interpretation is difficult: it may be that some form of ritual deposit is indicated; alternatively, the enclosure could have been used for slaughtering surplus stock at certain times of the year, the worthless parts of the carcasses, including the heads, being discarded before the rest was carried off. The two explanations are not mutually exclusive. The Harrow Hill enclosure has much in common with the enclosures of Dorset and Wiltshire described above (pp. 46–7), but its more substantial earthworks and prominent hill-top location serve to distinguish it.

The second enclosure, Ram’s Hill, is situated in a similar position on the crest of the Berkshire Downs. Although it has been virtually flattened by ploughing, a recent campaign of excavation has brought to light many structural details and has allowed the excavators to propose a three- phase sequence. In the first phase an area of about 1 ha was enclosed by a flat-bottomed ditch 2 m deep, backed by a bank faced with chalk blocks. It appears that, at a later stage, the bank was faced with a palisade of timbers tied back to an inner row of verticals, to create a box- structured rampart. Finally, a little later, a double palisade was erected in front of the rampart, set largely within the filling of the ditch. One principal entrance and a small subsidiary gate were excavated, but two others are apparent on the air photographs. Radiocarbon dating reassessed by Needham and Ambers (1994) suggests that occupation lay within the thirteenth to the tenth centuries BC. Internally a few post-holes were recovered, some possibly belonging to circular huts, others to regular settings of four posts of a kind thought to represent granaries. Finds were sparse, but one notable observation was that the pottery displayed a very wide range of fabrics, suggesting perhaps use by communities coming from far afield. It is possible, therefore, that at some stage Ram’s Hill was used for a communal, perhaps socio-religious, purpose.

Ram’s Hill, Harrow Hill and two similar enclosures at Highdown Hill, Sussex, and Norton Fitzwarren, Somerset, are sufficiently comparable in size, structure and date to suggest that they may have performed similar economic, social or religious functions in their respective regions, but more than this it is difficult to state. They do however seem to differ significantly from the ‘pastoral enclosures’ and the farms described above, and it is not unreasonable to suppose that they may have served a community larger than the extended family group. The distribution of Bronze Age farms on the hill slopes around Harrow Hill gives the impression that the hilltop enclosure was a central point of a territory containing a number of scattered farming communities.

If the hill-top enclosures represent a degree of social cohesion, it is reasonable to ask whether a higher level of selected location can be defined, reflecting perhaps tribal gatherings. One type of site, which can be called the plateau enclosure, seems to be relevant here. A number of high hill-top locations can be shown to have been partially enclosed by lengths of bank and ditch thrown across spurs in such a way as to define relatively large flat areas of hill-top. Characteristically the banks are on the outside of the ditches (Cunliffe 1972b, 1976b). A selection of sites of this type are illustrated here (Figure 3.11). Others possibly include the spur dykes on Hamble- don Hill, Dorset, the earthworks on Minchinhampton Common, Glos., and, further afield, the earthwork on Ratlinghope/Stitt Hill, Shropshire. Sites of this type have been very little studied and are virtually undated, but the Hambledon Hill spur dykes, if they belong to this category, have a third-millennium date indicated by radiocarbon assessments. In our present state of ignorance it is safer to recognize the existence of plateau enclosures without attempting to assign a date range or function to them.

The south-west peninsula

Another area to have received detailed study is the south-west peninsula, particularly Dartmoor, Exmoor and Penwith. Of these regions, the settlement history of Dartmoor is the most informative, not least because of the attention which it has received from soil scientists and palaeobiolo- gists, enabling regional ecological variations to be mapped in relation to the contemporary settlement patterns (Figure 3.12) (Simmons 1970). It is now clear that in the Middle to Late Bronze Age the high moorland areas above the 427 m contour were already covered with a blanket bog in excess of 0.6 m in depth. Below this and down to approximately the 243 m contour, the upper limit of the thick forest, lay a densely settled area of open grassland or heath- land interspersed with relict woodland. The open areas originated in the coalescence of clearings which began at the beginning of the third millennium or even a few centuries earlier. Once the forest cover had been removed, continuous grazing and the leaching effect of heavy rainfall prevented forest regeneration.

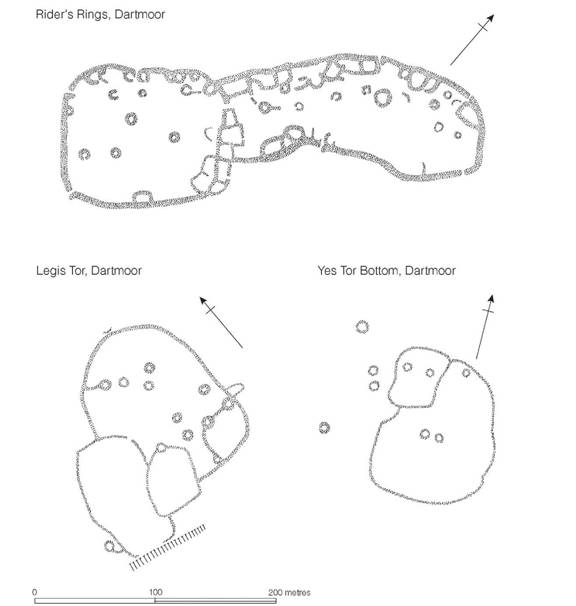

Three types of settlement have been defined, each showing some preference for a different ecological zone. The first, the pastoral enclosures, are concentrated on the south side of the moor, usually on south-facing slopes above river valleys close to a water supply (Figure 3.13). These enclosures have substantial walls, inside which lie scattered stone-built huts usually in sufficient numbers for the settlements to be considered as villages. While it is not impossible that small- scale cultivation was carried out within the enclosed area – and indeed at Rider’s Rings there are several small, walled garden plots – evidence of agricultural activity on a large scale is lacking. Some of these settlements show signs of growth. At Legis Tor a sequence of walls can be traced, demonstrating that the enclosed area was greatly increased in three successive stages, but whether this was related to a growth in the size of the population is impossible to say.

Only one site in this general category, Shaugh Moor, in the valley of the River Plym, has been extensively examined by modern methods (Figure 3.14). Here a complex of linear boundaries, burial cairns and walled enclosures litter the moor. One of the enclosures, selected for total excavation, was oval in shape, some 75 m across the large axis and was surrounded by a stone-built wall without gates. Within lay five stone-walled huts, with internal timber supports, arranged around the periphery, together with a scatter of post-holes in the central area. The range of radiocarbon dates suggests continuous use throughout the second millennium until the ninth century (Otlet and Walker 1982, 237). Finds were sparse but included quernstones, flint scrapers and a little pottery. The virtual absence of grain (in spite of an extensive programme of sieving) and the comparatively few querns covering the 1,000 years or so of use tends to support the view that the enclosure reflected a pastoral aspect of the economy. One scenario would be to see enclosures of this sort used by a segment of the population who spent the summers on the move tending the livestock, and collecting metal ore as a major ancillary activity. Indeed, it may be that the density of settlement around the western and southern fringes of the Moor is a reflection of the rich alluvial tin resources available in this zone (Price 1985, 1993).

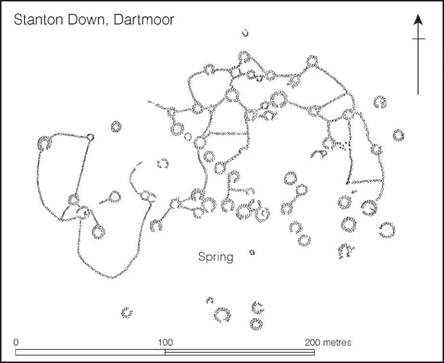

The second type of Dartmoor settlement is the unenclosed village, where clusters of circular huts are linked together by low stone walls, creating multi-angular enclosures which could well have served as both cultivation plots and paddocks for stock at different times of the year. Sometimes these villages reach considerable proportions – sixty-eight huts are recorded at Stanton Down (Figure 3.15) but not all are so strictly nucleated: at Rough Tor on Bodmin Moor, for example, huts and their attached enclosures spread for about 0.8 km along a track, but here we may well be dealing with a linear development representing settlement shift over a considerable period of time. Unenclosed villages are not particularly numerous; with rare exceptions,they concentrate on the climatically wetter western fringes of Dartmoor, usually within easy reach of streams.

Figure 3.11 Plateau enclosures on the chalk downs. All plans are orientated with north at the top; contours at 100 ft intervals. The cross-symbols represent the positions of Romano-Celtic temples (source: author).

Figure 3.12 The ecology and settlement pattern on Dartmoor, late second to early first millennium (source: I.G. Simmons 1970).

Figure 3.13 Nucleated settlements on Dartmoor, late second to early first millennium (sources: Rider’s Rings, Worth 1935; Legιs Tor, Worth 1943; Yes Tor Bottom, Worth 1943).

Figure 3.14 Shaugh Moor, Dartmoor, showing the enclosure fully excavated (photograph: Geoffrey Wainwright).

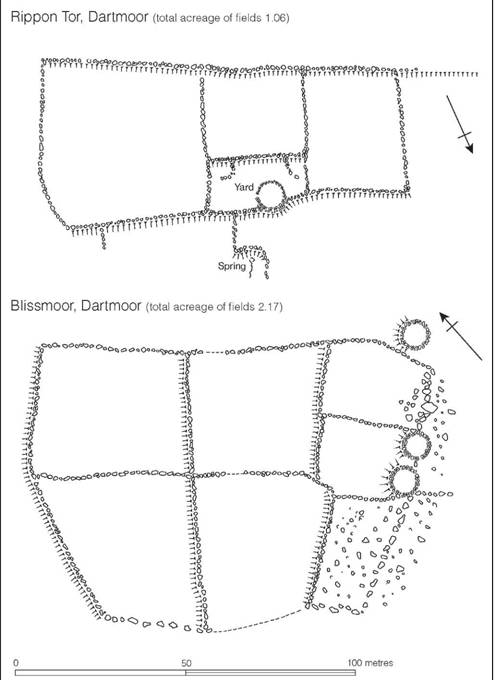

The third type of settlement is the isolated farm or group of farms found in intimate association with rectangular stone-walled fields (Figure 3.16). Several such settlements are known in their entirety, showing that the arable area is hardly likely to have produced sufficient food for the occupants – only 0.4 ha for the single-hut farm at Rippon Tor and 0.8 ha for the three huts at Blissmoor. The implication must be that additional food supplies were available, presumably in the form of flocks and herds reared on the upland pastures. The arable farms cluster to the east of Dartmoor on the fertile ‘brown soils’, sheltered from extremes of climate by the mass of the moor itself. The dating of these sites presents some difficulties since material finds are sparse. Comparisons of the pottery from the Dartmoor settlements with the better-dated Cornish sequence, however, suggests a Middle Bronze Age date (Read 1970). This gains some support from the discovery of a ‘Bohemian style’ palstave dated approximately to the fourteenth to twelfth century, found in relation to a field system on Horridge Common (Fox and Britton 1970, 225).

It would appear that the large pastoral villages and the small arable farms are different responses to different environments, and it may well be that they represent two divergent subsistence economies, but the possibility remains that this is the archaeological evidence of a transhumant society – the population leaving the scattered farmsteads of the east during the spring and summer, taking their herds and flocks to the wetter western pastures, to return again in time for harvest. Some form of transhumance is certainly implied by the small hectarage of the eastern group of farms. It has been argued, however, that in addition to an important pastoral component an infield–outfield system of farming was being practised, the small areas of enclosed fields representing only the infields (Denford 1975).

Figure 3.15 A Dartmoor village of the late second to early first millennium (source: Baring-Gould 1902).

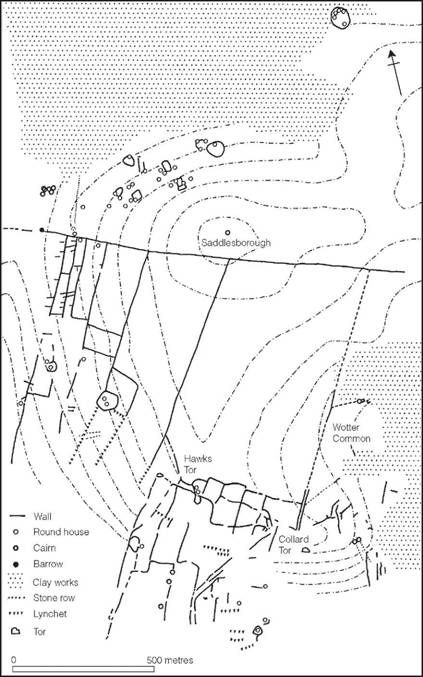

Intensive field survey on the south edge of Dartmoor in the Cholwich Town region has shown that large areas of moorland were enclosed at this time by linear banks of stone known as reaves (Figure 3.17) to which enclosed settlements were attached (Fleming 1978, 1984, 1988, 1996). Whether the boundaries divided territories in different ownership or land subject to different usage is unclear, but the extent of the reave system and the associated huts and settlements leave little doubt that the population was large and the available land well organized.

Further west, in Cornwall, structural evidence for Middle to Late Bronze Age settlement is less prolific, although the settlement stratified beneath the Iron Age round at Trevisker is a reminder that many of the locations chosen for later settlement may well have been occupied on one or more previous occasions. The single radiocarbon date from the site suggests occupation in the thirteenth century BC. The wide distribution of Trevisker style pottery (Parker Pearson 1990, 16–20) implies the existence in Cornwall of an extensive and settled population, utilizing the best farming land. On the more marginal lands, on the fringes of the granite moors, clusters of circular stone-built huts, like those of Dartmoor, are well known, but few have been extensively examined. At Stannon Down, on the western edge of Bodmin Moor, however, a group of eighteen houses apparently associated with corrals and strip fields have been planned and partially excavated. Estimates of population and crop yield suggest that here, as on Dartmoor, an infield–outfield system and a significant pastoral element would have been necessary to supply the needs of the community. In comparison with Dartmoor, Bodmin Moor appears to have been far less intensively occupied (Johnson and Rose 1994).

Figure 3.16 Dartmoor farmsteads of the late second to early first millennium (source: A. Fox 1955).

Figure 3.17 Reaves on Dartmoor. The system on Shaugh Moor and Wotter Common (source: Smith, Coppen, Wainwright and Beckett 1981).

The Midlands and Wales

Much of what has been said of the settlement pattern and economy of southern Britain must apply to the rest of the country but at present the evidence is, to say the least, sparse. In Wales several inhabited cave sites of the period have been defined, e.g. Lesser Garth Cave, Radyr, and Culver Hole Cave, Llangenydd (Gower), but open settlements are rarer. The ring-work on Marros Mountain, Pendine, may have been occupied at this time, but the evidence is not conclusive and it may possibly belong to the later first millennium. The above-mentioned sites all produced pottery in the Late Bronze Age tradition but little is known of other aspects of the material culture and economy – except, of course, for the numerous bronze hoards.

The Midlands and north are no better known. Work at Mam Tor, Derbyshire, has however demonstrated the existence of a cluster of Bronze Age huts producing radiocarbon dates of 1530–1260 and 1470–1210 Cal BC, sited on the top of a hill later enclosed by the bank and ditch of an Iron Age hillfort. At the neighbouring hillfort of Portfield, Lancs., the discovery of a Late Bronze Age hoard lends some support to the idea that many of the hill-tops later fortified in the Iron Age may have originated as settlements even as early as the late second millennium.

The north and north-west of Britain

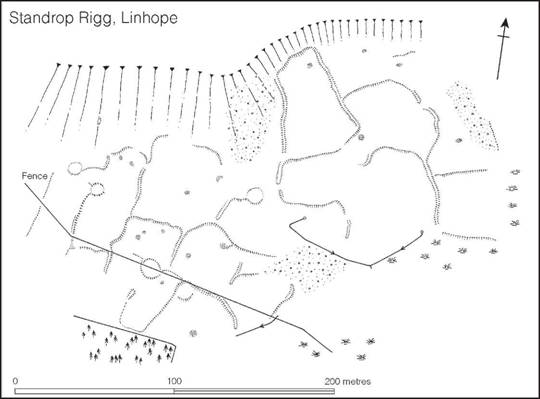

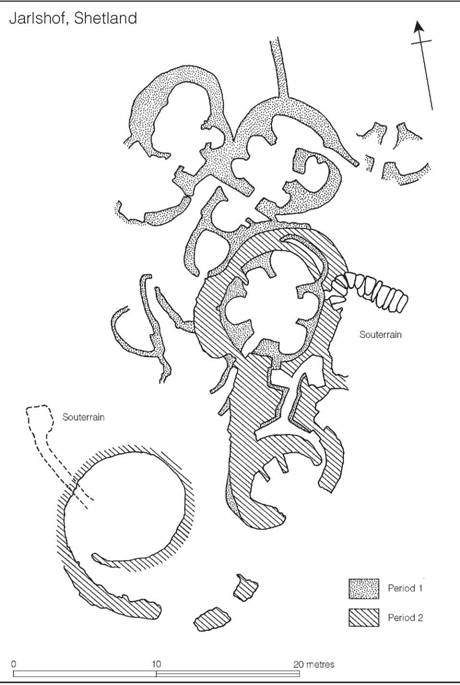

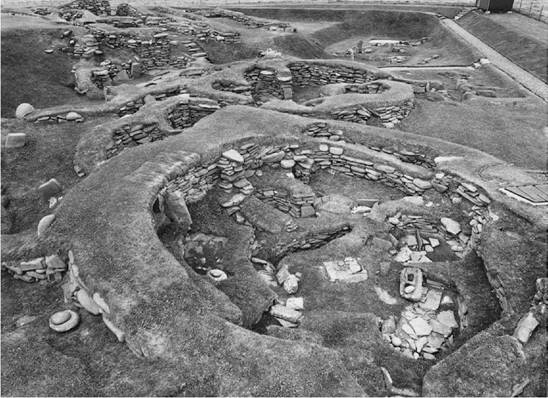

In northern Britain it is now clear that many, if not all, of the unenclosed hut sites found in upland areas belong to the later Bronze Age (Jobey 1980). The most extensively excavated are the clusters at Green Knowe, Peeblesshire, and Standrop Rigg, Northumberland (Figure 3.18) for which radiocarbon dates focusing on the last three centuries of the second millennium BC have been obtained. Sites of this kind lie at the upper limit of prehistoric land exploitation and owe their survival to the fact that they have escaped the ravages of later agricultural activities. Other classes of settlement are less well known. Clusters of hut circles in the Yorkshire Dales, e.g. at Grassington, occasional cave deposits as at Covesea (Moray) and Heathery Burn, Co. Durham, the so-called crannogs of eastern Yorkshire and parts of Scotland and the cellular stone houses of Jarlshof (Figures 3.19 and 3.20) and Sumburgh on Shetland, are all part of an extensive and varied settlement pattern about which few details are known. The general impression which these fragments provide is of well-established communities not unlike those of the southeast, which had adapted themselves closely to the far more varied environments of the west and north. In the absence of positive evidence to the contrary, it would seem likely that the economy was heavily dependent upon pastoralism, cereal-production including the cultivation of barley and emmer wheat playing a lesser but still significant part (Halliday 1993). In this respect it is worth noting that the upland settlement of Green Knowe lay within a landscape that was being cleared of boulders either to improve pasture or to provide scope for cultivation. Views on this matter are, however, liable to modification in the light of ongoing work (Cowie and Shepherd 1997).

Figure 3.18 Standrop Rigg, Northumberland. Settlement of the late second to early first millennium (source: Jobey 1983).

Pottery

The dating of pottery belonging to the period 1500–700 BC is fraught with difficulties, and detailed discussion is not directly relevant to this volume (but see Barrett 1976, 1980). Nevertheless, some generalizations must be made, if only to prepare the way for the more lengthy consideration of the later period in subsequent chapters. The south-east of Britain, south of the Severn–Wash axis, has produced a large amount of pottery of Middle to Late Bronze Age date which used to be classed together under the general title of the Deverel–Rimbury culture (Preston and Hawkes 1933), a name derived from two Dorset cemeteries excavated in the nineteenth century. Pottery of Deverel–Rimbury type has been recovered from two main contexts: cremation cemeteries and settlement sites of the types already described. In the cemeteries it is seldom found in any form of association with datable metalwork, but at the settlements bronze implements are occasionally found and can be used to provide broad date-brackets for the pottery.

An assessment of the associated bronzes (Smith 1959) has shown that they ran broadly contemporary with the Montelius III phase of the north European Bronze Age, currently dated to 1300–1100 BC. This dating for an early stage of the Deverel–Rimbury culture gains further support from a typological study of the individual ceramic forms, which suggests internal development from indigenous types independently dated to the middle of the second millennium. Further confirmation is offered by an increasing number of radiocarbon dates. Thus the date- bracket 1400–1000 may reasonably be proposed to contain the ‘classic’ Deverel–Rimbury culture.

Figure 3.19 Late Bronze Age homestead at Jarlshof, Shetland (source: J.R.C. Hamilton 1956).

Figure 3.20 Jarlshof, Shetland. The houses of the Bronze and Iron Age settlement (Crown Copyright reserved).

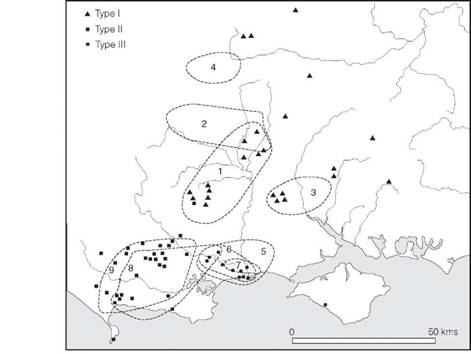

Within the ceramic assemblages of this ‘classic’ phase it is possible to recognize a number of regional variations evident in the fine wares which partly reflect the basic folk tradition of the region and partly local inventiveness (Figure 3.21). These differences may be used to define regional groups. Thus in Devon and Cornwall lies the Trevisker group (ApSimon and Greenfield 1972; Parker Pearson 1990), in Dorset, south and west of the Stour, is the South Dorset group, on the Dorset coast at the confluence of the Stour and Avon is the Stour valley group and in Wiltshire and south-east Hampshire is the Cranborne Chase group (Calkin 1964; Ellison 1981). The contemporary pottery of Sussex differs significantly enough from the western groups to be considered as a separate South Downs group, and in Essex and Suffolk the Ardleigh group has been distinguished (Erith and Longworth 1960). Other regional groups can be isolated in the Thames valley, the west Midlands and the east Midlands (Burgess 1974, 214–15).

The characteristic fine wares which enable the regional groups to be defined do not seem to have lasted long after 1000 BC, though in parts of northern Wessex the tradition may have lingered (Gingell 1980; Cunliffe 2000, 149–50). For much of the country the period from c. 1100 to 800 is marked by an intense conservatism in pottery technology, during which time the barrel and bucket types continued to be made but in a simplified range of forms. This phase may reasonably be called Late Deverel–Rimbury. Eventually, during the eighth century, or perhaps a little earlier in some precocious regions, innovations appeared alongside traditional forms: large angular jars were manufactured probably in imitation of bronze situlae, a range of bowls appeared and a few vessels in peripheral Urnfield style are to be found in the south-east. This phase of innovation has been called Ultimate Deverel–Rimbury (Cunliffe 1978a, 27) or Post Deverel–Rimbury (Barrett 1980). Neither term is entirely satisfactory: here it is proposed to refer to it with the less emotive term LBA transitional phase. These ninth- to eighth-century innovations heralded the development of an inventive and dynamic ceramic industry in the south and east of the country which can properly be considered to be Iron Age.

Figure 3.21 Distribution of Deverel–Rimbury pottery styles (source: Ellison 1981).

In the Midlands, Wales and much of the north, pottery gradually ceased to be a significant element of material culture and many areas became virtually aceramic. Several urnfields have, however, been recorded in central England, including a large cemetery at Bromfield, Salop, where a series of cremations has been dated from roughly the seventeenth to ninth centuries BC.

In the extreme north of Scotland, in the Hebrides, Orkneys and Shetlands, a well-established ceramic tradition, rooted ultimately in the third millennium but with French Urnfield influences, flourished throughout this period and well into the Iron Age.

The bronze industry

In the foregoing pages emphasis has been placed on the indigenous development of the British Late Bronze Age communities and the relative self-sufficiency of their subsistence economies. Superimposed upon this pattern of intense regionalism is a complicated and wide-flung exchange system best exemplified by the distribution of bronze weapons and implements. Exchange was on two levels: overseas, which brought in exotic types – often copied locally – and local, distributing the products of British smiths over more limited territories. This kind of specialist activity had a long ancestry in Britain; the Late Bronze Age was to see its ultimate development and the beginning of its decline.

The question of chronology has been much debated in the past and has involved complex typological arguments often open to much uncertainty. A recent systematic programme of radiocarbon dating (Needham et al. 1997) has led to the development of an independent chronology which is used here. It has shown that previously accepted dates were conservatively late.

The general bronze assemblage of thirteenth- to twelfth-century date contains a wide range of implements, including flange-hilted, leaf-shaped swords based on imported Erbenheim and Hemigkofen weapons; leaf-shaped Ballintober swords; dirks; looped palstaves; experimental types of socketed axe; basal-looped spearheads; razors and ring-socketed sickles. Distribution of these types is wide but centres upon south-eastern England. In the south it is generally known as the Penard phase, after a Glamorganshire hoard; in Scotland it is represented in the Glentrool tradition. Connections were wide, linking England and Scotland to Wales, Ireland and the northern and western areas of France.

From the middle of the twelfth century until the end of the eleventh, Britain south of the Humber was served by bronze smiths casting a range of new implements in bronze with a high lead content, a technical practice which was to last in the south for some centuries. These new types constitute what is known as the Wilburton complex: they include leaf-shaped swords with splayed V-shaped shoulders, long tongue-shaped chapes, simple-socketed spearheads pegged into position on the shaft, late types of palstaves and socketed axes. Again trading connections were maintained between southern Britain and north-west France, but the new types do not appear to have penetrated far into northern England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland. In these regions, traditions and technology harking back to the preceding phases remained dominant. In northern Britain, for example, where the broadly contemporary assemblage is known as the Wallington complex, some of the implements such as the side-looped spearhead and low-flanged palstave are close to types developed before the eleventh century. In Wales, too, early types continued in use to the ninth century, although late hoards in the Wilburton tradition are found in the Upper Severn valley. A similarly retarded industry, called the Poldar phase (Coles 1962b), has been defined for Scotland, where a number of Wilburton and Wallington types have turned up, but only in small quantities. Most of the elements of ninth- to eighth-century metallurgy belonging to the Wilburton complex are represented in a remarkable founder’s hoard discovered in 1959 at Isleham, Cambs., where some 6,500 fragments of bronze were found buried in a small pit cut into the chalk. In addition to weapons of Wilburton Complex type, the hoard contained fragments of bronze cauldrons and a series of harness fittings which included cheek- pieces, annular strap-crossings and cruciform strap-crossings. Thus this single hoard exemplifies most aspects of the developed bronze technology and trading systems of the period, while the presence of the bronze harness trappings and the cauldron fragments reflects new elements, which we shall find recurring more frequently in hoards of the later eighth, seventh and sixth centuries.

In south-eastern Britain the tenth century is a period of rapid typological change. At present it is not well defined but is typified by the hoard found at Blackmoor after which the phase has been named.

At the end of the tenth century south and east Britain developed a series of new types in parallel with the western areas of France, with which close contacts were maintained, but now on a more intensive scale. The new assemblage, known after the site of Ewart Park, incorporates Continental material of the Carp’s-Tongue Sword Complex (Savory 1948; Briard 1965), including the long sword with a narrowed point (after which the industry is named), characteristic bag-shaped chapes, knives of hog’s back and triangular form, various types of socketed axe, socketed knives, pegged and socketed spearheads, various chisels and gouges, and several decorative attachments of which the so-called ‘bugle-shaped’ objects are the most characteristic (Figure 4.5, p. 77). In Britain the locally produced leaf-shaped sword of Ewart Park type occurs in considerable numbers throughout the whole of the country and serves as a linking feature between the Carp’s-Tongue Sword Complex of the south-east and the regional industries of the north and west, which can be defined largely by typological variations in their socketed axes.

In addition to the cast bronze implements just described, vessels and shields of beaten bronze make their appearance in the British Isles from the tenth century, or perhaps a little earlier, as a result of far-flung contacts with central Europe. One group of vessels to arrive, the high- shouldered situlae known as Kurd buckets, find their way into Wales and Ireland, where some were modified by Irish smiths and later copied, giving rise to a distinctive Irish-British type which appeared in small numbers in the north and west in the first half of the seventh century (Figures 17.1, p. 448 and 17.6, p. 454). Broadly contemporary was the manufacture of bronze cauldrons, the earliest of which, from Colchester and Shipton, are thought to have originated at the end of the second millennium in the wake of contacts with central Europe and were probably manufactured in southern Britain. Early in the first millennium Ireland seems to have taken over as the main production centre (Gerloff 1987) whence cauldrons were exported along the Atlantic sea-ways.

The duality of the exchange contacts between Britain and the Continent implied by the importation of bronze vessels – a central European Rhine route and possibly a Mediterranean Atlantic route – is also reflected in the origins of the beaten bronze shields, which give rise to local types widely distributed over most of the British Isles by the eighth century (Coles 1962a). More recent work has indicated a possible Hungarian origin for the type a century or two earlier and the transmission of the idea may have come via Denmark (Burgess 1974, 205; Thrane 1975, 79–81). Other exotic types found their way in at this time, principally from central and northern Europe. Among these must be mentioned the first appearance of bronze fittings appropriate to horse harness, which surely implies the introduction of more sophisticated methods of harnessing and possibly the greatly increased practice of horse-riding. Such developments are largely in parallel with those discernible in Europe during the Hallstatt B phase of the Urnfield culture.

Behind the complexity and the detail of the early first-millennium bronze industry, it is possible to discern several general trends, not the least of which is the development of numerous local schools of craftsmen specializing in the production of the more sophisticated objects such as the buckets, cauldrons and shields, all in beaten metal. The swords too, with their rapid and subtle evolution, were clearly made by specialists; many of these, to judge by the distribution pattern, were centred upon the Lower Thames, where new foreign imports were evidently carefully studied and improved upon. Less skill would have been required for the production of the smaller cast implements and, as might be expected, intensive regionalization is recognizable, representing the distribution of the products of single smiths or, at the most, small schools; craftsmen in the remoter parts sometimes worked in alloys and made types long outdated by advances in the more forward areas. In the south-east innovations kept appearing, partly because of native inventiveness and partly because of widespread trading contacts, particularly with northern and western France, which were maintained over several centuries. Thus by the end of the eighth century a wide range of weapons, tools, ornaments and other utensils was being manufactured and traded on an unprecedented scale, vigorous local production centres maintained high standards of inventiveness, and a common market existed between Britain and Atlantic Europe. Superimposed upon this was a well-defined pattern of smaller-scale exchanges with northern Europe across the North Sea. It was with this area that the first contacts with the Hallstatt C communities of the eighth to seventh century developed.

Burials

The best-known aspect of the culture of the thirteenth to eighth century is the burial rite (Ellison 1980a; Bradley 1981). The dead were cremated and frequently, but by no means invariably, placed in urns, sometimes buried in urnfields of considerable size: more than 100 burials at Ardleigh, Essex; 104 at Moordown, Bournemouth and 100+ at Kimpton, Hants. In many cases it can be shown that urnfields grew up around earlier barrows, as, for example, at Steyning, Sussex, where at least thirty-two urned and four un-urned cremations were inserted into an existing Middle Bronze Age barrow; at Latch Farm, Hants, more than ninety cremations, mostly urned, were found in a similar relationship. A further example is provided by the small barrow just north of the Itford Hill settlement. Here the central cremation was contained in a Middle Bronze Age urn to one side of which was a group of cremations representing between fourteen and nineteen individuals, some contained in vessels closely similar to those found on the settlement site. Presumably this cemetery, together perhaps with others, served the settlement. It is tempting to see the burials as those of a single kinship group.

Another impressive example of continuity is provided by the cemetery at Kimpton, Hants. The cemetery began in the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age focused on one or more large sarsen stones and developed as an urn cemetery associated with a complex platform of flints, the latest burials dating to the end of the seventh century BC. Thus it remained in use as a burial place for a period of some 1,500 years.

The Latch Farm excavation gives a clear indication of the range of burial ritual employed: frequently cremations were in upended urns placed in shallow pits; sometimes, however, the pots were set upright in the ground and in several cases subsidiary vessels, presumably containing offerings of food and drink, were included. Some examples, usually those placed upright, were covered with stone slabs set flush with the surface of the ground and were therefore possibly intended to be visible. Two post-holes were also recognized, which might have belonged to wooden markers. The burials are usually clustered together without apparent order, but sometimes, as at Ardleigh and at Pokesdown, Hants, groups and isolated burials were strung out in a linear arrangement which suggests the directional growth of the cemetery. At Barnes, Isle of Wight, between ten and fifteen urns were laid in a circle, 3–4 m in diameter, implying a considerable degree of forward planning, unless it is assumed that all the cremations were interred at the same time.

Burial beneath barrows continued alongside the urnfield rite. In Wessex it is estimated that 12 per cent of the excavated barrows contained primary Deverel–Rimbury cremations but the barrows are generally only about half the size of the earlier barrows. A typical example was excavated at Plaitford, Hants, where two urns were found set in a shallow pit beneath a small cairn of clay, sand and pebbles, in which had been set a vertical marker post. Over the cairn had been heaped a circular mound 1.5 m high and 10.7 m in diameter. The use of a vertical marker post has also been noted at several urnfield sites.

The urnfield rite was also practised in other parts of the country. At Bromfield, Salop, an arc- shaped urnfield of urned and un-urned cremations has been totally excavated, producing three radiocarbon dates from the seventh to the ninth centuries. Another urnfield at Ryton-on- Dunsmoor, Warwickshire, yielded a series of dates from the tenth to ninth centuries. In Wales and Scotland urnfields are rare, but urned burials are often found as secondary interments in earlier barrows and cairns, and less frequently as primary burials beneath small cairns.

Regional and interregional systems

In recent years much effort has been expended in an attempt to formulate the social and economic systems which allowed the later Bronze Age communities to articulate, and to discover, the trajectories of development apparent in the period as a whole. This work is, of necessity, based on a grossly inadequate database and is highly speculative even though the individual theories appear to have a degree of coherence within the available data. Yet, putting these reservations aside, a number of valuable generalizing statements can be made.

Perhaps the most striking observation to emerge is the massive cultural continuity which spans the period from about 2000–700 BC. Traditional burial sites continue to be used throughout (Ellison 1980a) and there is an increasing body of evidence to suggest a degree of continuity in the choice of settlement locations (e.g. Gingell 1980). Against this background may be placed the dynamics of climatic change. Current work suggests a climatic optimum in the period 1300–1000 BC and a rapid decline in the next three centuries. The magnitude of these changes cannot have failed to have affected marginal areas such as the moors of the south-west, the Welsh hills and the northern uplands where considerable fluctuations would have occurred in the maximum altitude of effective cultivation. In the south-east it is doubtful if the local communities noticed the change at all. Burgess (1985) has hypothesized a period of disease and rapid population decline concurrent with the climatic deterioration beginning about 1000 BC. The model he uses, based on Roman and medieval evidence, may not, however, be entirely applicable in a non-urban situation.

Another factor needing to be considered is the possible effect on fertility of the eruption of the Hekla volcano on Iceland in 1159 BC. The eruption sent huge clouds of ash into the atmosphere and traces of it have been identified in Scottish peat bogs. Mike Baillie, studying tree rings of the period from samples found in Ireland, has argued convincingly of decade-long ‘biological catastrophe’ during which time there was hardly any tree ring growth (Baillie 1995). Whether or not the eruption caused widespread devastation throughout the British Isles is a matter of debate (Buckland et al. 1997) which will only be resolved by the discovery of suitable dendrochrono- logical samples from elsewhere in the country.

Developments in British bronze technology must be seen in the broader European scene. The demand for raw materials such as tin and to a lesser extent copper, by the developing Mediterranean states, created a complex network of trade and exchange which bound the coastal communities of southern Britain closely to the Continent, thus ensuring a constant interchange of ideas and technology. Various regions of Britain, favoured by virtue of their geographical location, such as the Thames valley and the Solent coast, remained significant interfaces between Britain and the Continent throughout much of the period and were, not surprisingly, zones of innovation.

On a more regional scale the Middle and Late Bronze Age of southern Britain, where the dataset is now considerable, has been subjected to detailed consideration (Ellison 1980b, 1981). Sites like Norton Fitzwarren, Martin Down, Rams Hill and Highdown are seen as foci where regional exchange was articulated, while the study of artefact distribution demonstrates a complex system of small-scale interlinking exchange networks the origin of which is thought to lie in the development of an established mixed farming regime after the middle of the second millennium. This development paves the way for what is to follow in the Iron Age.

Attempts have also been made to consider the relationship of the chalklands of southern Britain and their peripheral interfaces with the Continent – the Thames valley and the Solent coast (Barrett and Bradley 1980b and c; Bradley 1980, 1981). The early Deverel–Rimbury cemeteries of the Solent are here seen as broadly contemporary with the rich Wessex burials of inland Wessex, the coastal zone growing in strength as the wealth of the inland communities declined in the thirteenth and twelfth centuries. By the end of the Bronze Age the Wessex communities are thought to be in a state of stress, with large areas, previously arable, being abandoned and perhaps given over to cattle ranching, while the centre of innovation now focuses on the Thames corridor. Views such as these, while inherently plausible, depend on close chronological arguments based on radiocarbon dates and may well prove to be oversimple generalizations. None the less the exercise has considerable value in focusing on the social dynamics which must lie behind the patterning evident in the archaeological material.

The Middle to Late Bronze Age was a period of transition from the simple agricultural regimes of Neolithic to Early Bronze Age, to the settled and intensive exploitation which typified the Iron Age and Roman period. The economic strategies, settlement patterns and much of the technology developed in the period 1500–700 BC paved the way for the Iron Age, and in the emergence of a hierarchic social system, evident in the diversity of settlement type from about 1000 BC, we can discern one of the principal motive forces which was to dominate the later first millennium.