12

Settlement and the settlement pattern in the south-east

When Aulus Plautius established the Fosse frontier in the years AD 44–7 he was simply emphasizing a geographical and political truth. Britain could be divided into two parts about a line drawn along the Jurassic Ridge from Lincoln to Lyme Bay. To the south and east lay a densely settled region with authority centralized about oppida and with a subsistence economy depending to a large extent on the production of grain. To the north and west settlement was more scattered and in places sparse, there was little centralization of power and, while cereals were widely grown, there appears to have been a greater reliance on stock rearing. To the Roman military mind the south-east was clearly the part to become a province, for grain was an immensely valuable commodity and arable farmers, because of their dependence upon the seasons, were sedentary and thus easier to control. Admittedly, Plautius was seeing Iron Age Britain at its most developed, after 150 years or more of close contact with the Continent, but this basic geographical divide was equally relevant in the earlier period and played a considerable part in influencing the form, density and distribution of settlements.

Settlement is a complex subject since settlements interact with landscape in a continuum of time. To parcel up the subject tidily for the purposes of discussion certain arbitrary divisions must be made. Settlements vary in size from single houses providing shelter for families to vast oppida encompassing a range of functions. In this chapter and the next two we will consider the lower end of this range – homestead, hamlet and village – leaving larger agglomerations like hill- forts and oppida, which represent coercive powers commanding a greater input of social effort, for separate treatment. Even so there will be some overlap, especially in the discussion of house form. There is a similar problem with subsistence economy, which is intimately bound up with settlement morphology and location, but to discuss it along with the settlements themselves would be cumbersome. Thus a separate chapter is devoted to food production, where there will be some discussion of the socio-economic systems which linked production strategies to settlement form.

The ridge of Jurassic limestone provides a convenient notional western limit for the southeastern zone but it is convenient to stray beyond it on occasion to include such areas as the Somerset wetlands, and the valleys of the Worcestershire Avon and the Trent. The south-eastern zone itself is geologically varied but the lighter soils of the limestone hills, the chalk uplands and the river gravels were particularly conducive to Iron Age agricultural techniques and were accordingly more densely settled than the less hospitable sands and the more densely wooded clay lands. These factors to a large extent influence the availability of archaeological data. It is on the chalklands of Wessex and the Sussex Downs and on the gravel terraces of the Midland rivers that most of the excavated sites lie, and these regions must of necessity bulk large in the discussion, but other smaller and more varied regions have also been included to show something of the range of sites available for study.

The settlements of the southern chalklands

The chalklands of Wessex and Sussex were densely occupied in the Iron Age and the number of known settlements runs into thousands, but of these fewer than thirty have been excavated on a scale sufficient to allow worthwhile generalizations to be made. In areas where systematic plotting from air photographs has been attempted, as for example between the Test and the Bourne (Palmer 1984), something of the complexity of the landscape and the great variety of settlement components can begin to be appreciated, emphasizing the problems inherent in any form of classification. Nevertheless certain recurring patterns emerge which allow ‘types’ to be defined, albeit tentatively.

Middle–Late Bronze Age settlements

The characteristics of the settlements belonging to the thirteenth to eighth centuries have already been referred to in some detail above (pp. 43–8). Normally the inhabited area was enclosed by a bank in which the timbers of a palisade or a thickset hedge were based (although traces do not always survive), and each enclosure was provided with a gate of simple construction. Within the enclosed area, which averaged 0.4–0.8 ha, was a simple circular hut, or sometimes more than one, arranged so as to leave sufficient space around for the more domestic activities of the farm to be carried out. Sometimes, as at New Barn Down, Sussex, the total settlement consisted of only two enclosures, but at Plumpton Plain A, Sussex, there were found to be at least three broadly contemporary huts arranged along a trackway, while at Itford Hill, Sussex, seven or eight conjoined enclosures, not all contemporary, were found, with at least three more isolated huts scattered further away. Evidently, while some settlements were individual farmsteads, others may have taken on the aspect of hamlets or even small villages.

The settlement at Shearplace Hill, Dorset, which belongs to the late second millennium, was enclosed by a substantial and well-cut ditch backed by a bank with no signs of a palisade but possibly capped by a thorn hedge. Ditches are also present at Boscombe Down East, Wilts., and various sites on the Marlborough Downs; but at the Sussex sites, most of which are early first millennium in date, ditches (if they occur at all) are insignificant features, the emphasis being placed more upon the palisade embedded in a bank. While, for the most part, Middle–Late Bronze Age settlements appear to be short-lived, a number of sites are known in eastern Hampshire, where rectangular enclosures of early first-millennium AD date continue to be occupied or are replaced by larger enclosures of Early Iron Age date. The sites include Meon Hill, New Buildings, Old Down Farm and probably Houghton Down (Cunliffe 2000, 152–4). How widespread continuity of this kind was it is difficult at present to say.

Palisaded enclosures

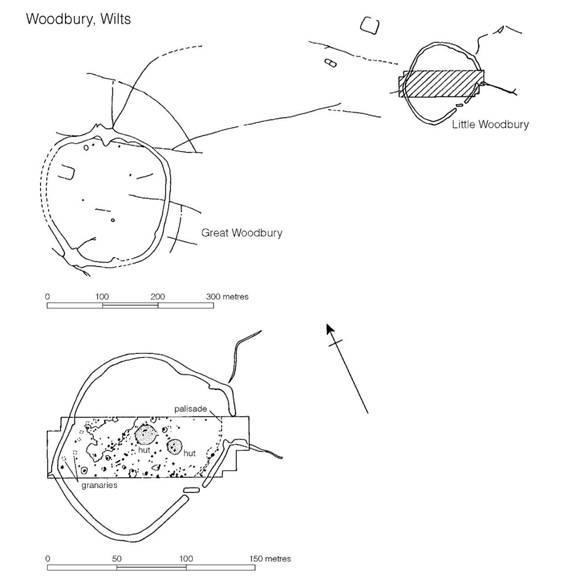

Palisaded enclosures containing settlements of various sizes are a common feature of Iron Age settlement pattern in eastern Scotland (pp. 312–18), but a widespread, if sporadic, occurrence over the rest of Britain is sufficient to show that enclosures of this kind were a normal element in the mid-first-millennium settlement pattern over many parts of the country. The most extensively excavated of the southern British palisaded settlements is Little Woodbury, Wilts., where two phases in the continuous occupation of the site can tentatively be recognized (see Figures 12.2 and 12.3). In the first phase the farm was enclosed by a palisade traced only on the east side, where a four-post gate – the principal entry to the compound – was uncovered. Within lay a large circular hut 13.7 m in diameter, with its entrance porch aligned exactly upon the gate.

The extent of the palisaded enclosure is unknown, but the ditched enclosure which replaced it defended about 1.6 ha, which may well approximate to the area of the original. Within the enclosure many domestic activities have left their mark. Behind the house lay a large irregular working hollow where grain parching and cooking were probably carried out. Corn was stored in rectangular four-post granaries, usually placed around the periphery of the enclosure, while hay, and possibly seed corn in the ear, was hung up on two-post racks to dry. At a later stage, in the fourth to second centuries, grain storage in large underground silos became widespread; these pits, later used for rubbish disposal, were found in large numbers. A high proportion of those from Little Woodbury relate to the later phase of the site’s occupation. Other aspects of the day-to-day routine were carried out within the enclosure – processes such as the grinding of corn, spinning, weaving, leather-working, basketry, etc., and on occasion animals in need of special attention may have been temporarily tethered inside.

The date of the early-phase occupation cannot be given with precision, but the earliest assemblage of pottery belongs to the All Cannings Cross–Meon Hill style, of the sixth to fifth centuries, while a few scraps of Kimmeridge–Caburn wares might suggest a beginning within the seventh century or a little earlier, but these fragments may be nothing more than the survival of archaic types.

The second Wiltshire site to have begun life as a palisaded enclosure is Swallowcliffe, where the initial occupation is approximately contemporary with that of Little Woodbury. The excavation, however, was carried out before the development of modern techniques, and apart from pits little else of structural significance was found. In Hampshire the excavations at Meon Hill and Houghton Down near Stockbridge (Figure 12.1) provided further evidence of palisaded settlements, again related to the All Cannings Cross–Meon Hill style of pottery. As at Little Woodbury, the old palisaded enclosure was replaced by a bank and a ditch of hillfort proportions. A further example of just such a replacement occurred at the Caburn, Sussex, in the phase pre-dating the hillfort. Here little of the early plan can now be recovered, but a length of palisade trench outside the entrance to the later fort and two huts just inside, together with several pits, represent the initial phase producing pottery of the Kimmeridge–Caburn style of seventh-century date.

Excavations at other southern British hillforts have occasionally suggested the pre-existence of palisaded settlements. Quarley Hill and Danebury, Hants, Blewburton Hill, Oxon., and Wilbury, Herts., have produced some evidence of early palisades but work has never been on a sufficient scale to show whether or not the later defences exactly followed the lines of the earlier enclosures. If they did, it would have to be supposed that fenced enclosures exceeding 6 ha in extent were being built in the first half of the first millennium.

Two other sites deserve mention: at Hollingbury and Park Brow, both in Sussex, trenches belonging to palisaded enclosures of rectangular plan have been partly excavated. Three sides of the Park Brow enclosure - each some 30-37 m - were examined, while at Hollingbury only one side 46 m long with a central entrance came to light. Since the plans are therefore incomplete and the enclosed areas have not been extensively excavated, speculation as to function is difficult, but these may have been specialized structures, perhaps even religious enclosures, and not settlement sites at all.

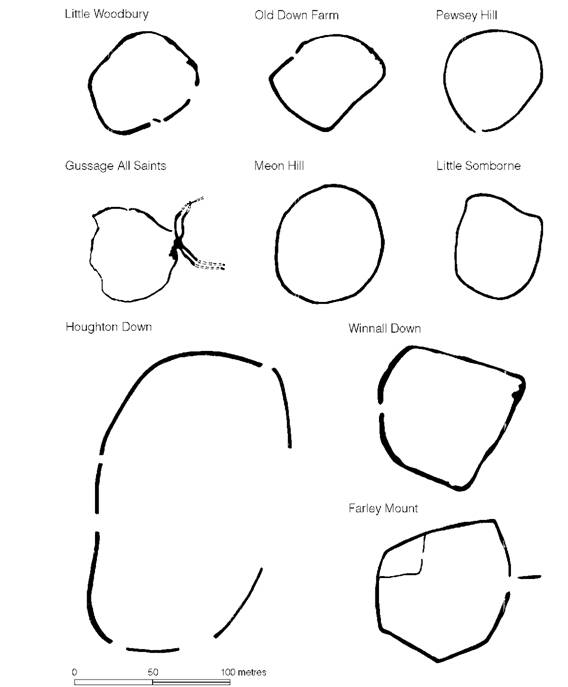

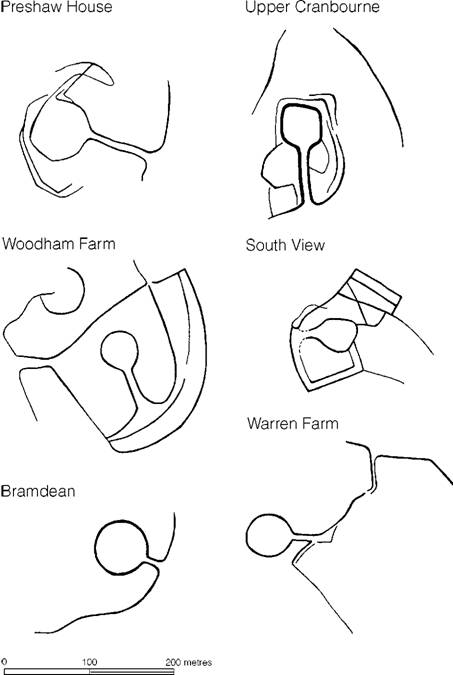

Figure 12.1 Settlements on the Wessex chalklands (source: Cunliffe 1984c based on various sources with additions).

Sufficient has been said to show that in the period from the seventh to the fifth century a number of settlements in southern Britain were surrounded by fences bedded in palisade trenches. Since the emphasis of the earlier first-millennium enclosures was also upon a vertical timber barrier rather than ditches or banks, it is not unreasonable to suppose that the later palisades were an indigenous development from these earlier beginnings. Details of the settlements themselves are few, but most of the recorded palisades enclosed individual farms and it may well be that most of the farms of the period were palisaded, but the point is difficult to demonstrate. That some of the hillforts were preceded by palisaded enclosures of comparable size shows that the palisade idea was not restricted to small settlements alone.

Earthwork-enclosed settlements (Figure 12.1)

At Little Woodbury, Meon Hill, Houghton Down and the Caburn, palisades had been replaced by ditched enclosures by the Middle Iron Age. The class of earthwork-enclosed settlement which they typify can usually, but not invariably, be shown to belong to this later period.

Little Woodbury in its later phase can be taken as a type-site for the class (Figures 12.2 and 12.3). Excavation has shown that the palisade was replaced by a ditch some 3.4 m wide by 2 m deep, which must once have been backed by a bank of chalk dug from it. The ditch enclosed a roughly circular area some 1.6 ha in extent, provided with a single wide entrance, apparently without a gate, from which two linear ditches radiated out like antennae.

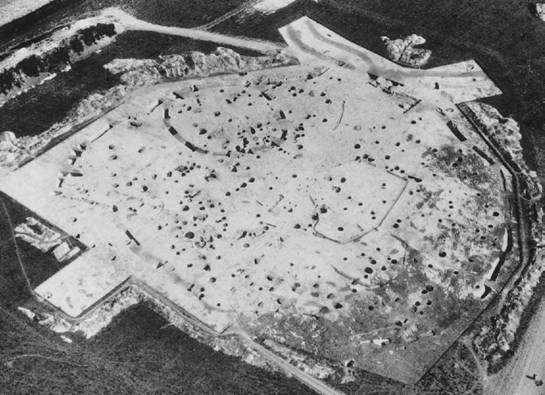

Even more informative has been the excavation at Gussage All Saints, Wilts., where two pre- Durotrigan phases have been recognized (Figures 12.1 and 12.4). In the first, which can be dated on the basis of radiocarbon assessment and artefacts to about the fifth century, a 1.2 ha enclosure was surrounded by a ditch 1.2 m wide and 0.8 m deep, apparently with an external bank. The enclosure was provided with a complex entrance flanked by antennae ditches. Within were found an area of pits and, towards the centre, a group of four-post structures of ‘granary’ type. No houses were recognized, but had there been stake-built structures all trace would have been destroyed by subsequent ploughing. In the second phase a more substantial ditch was dug, 2.2 m wide and 1.4 m deep, approximately on the line of the original ditch, and the entrance antennae ditches were remodelled on either side of an elaborate timber gateway. Within, pits continued to be dug and circular gullies indicate the locations of huts. Radiocarbon dates suggest that occupation lasted from the third to the second century, during which time undecorated saucepan pots were in use. Late in this sequence evidence of extensive bronze foundry activity was discovered (pp. 500-1).

At Old Down Farm, near Andover in Hampshire, a large-scale excavation of a 1.2 ha enclosure revealed a long-lived settlement (Figure 12.1). The earliest occupation began in the eighth century and may have been enclosed, but if so the ditch was almost entirely recut in the next phase dating to the seventh to sixth centuries, when a substantial ditch up to 2 m deep was dug around a settlement nucleus, leaving only one entrance (without any trace of a gate). Inside was a single substantial house, comparable to the early house at Little Woodbury, together with a scatter of storage pits. By the fifth century the ditch had largely silted but houses and pits still occupied the central area and occupation continued into the Middle Iron Age (fourth to early first centuries) though no houses have been identified. This absence of recognizable houses in the Middle Iron Age need occasion no surprise for it is now clear that in central southern England the normal house type in this period was built of wattlework, most traces of which would have been removed by ploughing, apart from the paired door-posts. Old Down Farm and Houghton Down are of particular interest in that they show that enclosure ditches, and presumably the banks and hedges going with them, were a feature of the Early Iron Age dating back possibly to as early as the seventh century. These early ditched enclosures must therefore have been contemporary with the early palisaded enclosures.

Figure 12.2 Little Woodbury, Wilts. (source: Bersu 1940).

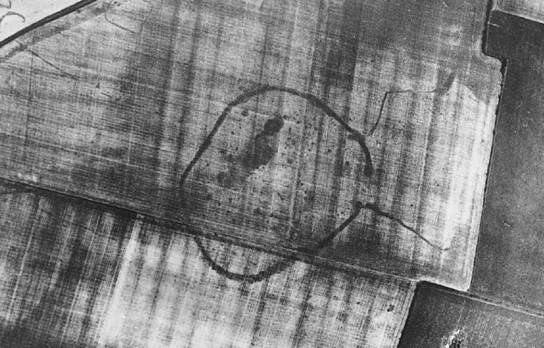

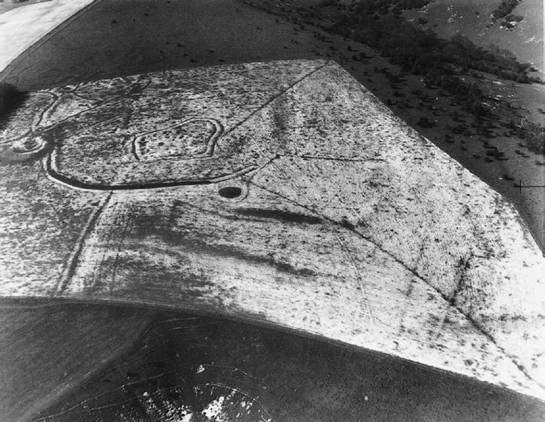

Figure 12.3 Little Woodbury, Wilts. from the air (Crown Copyright reserved).

Another site of outstanding interest is the settlement on Winnall Down near Winchester, Hants (Figure 12.1). Here in the sixth to fifth centuries a ditched enclosure comparable in size and shape to Old Down Farm was established on a site which had already been occupied in the Middle-Late Bronze Age. The single entrance was provided with an impressive gate and inside were a number of circular houses, storage pits and two- and four-post structures. Clearly not all were contemporary but several of the houses could have been in use at the same time. By the Middle Iron Age, not only had the ditch become silted but the settlement completely overrode the earlier boundary and was now divided into two distinct zones: a group of circular houses (and one rectangular structure), the majority of which could have been contemporary; and a zone of pits and four-post granaries. Some intercutting between the pits suggests a considerable duration of occupation.

Closely similar enclosures are known at an increasing number of sites recognized on air photographs and from partial excavations, but the few chosen for brief description above present the principal characteristics. Sizes range from about 0.6 ha at Mancombe Down, Wilts., to about 2.5 ha at Farley Mount, Hants, a range which may reflect the status of the individual owner and the size of his holding: some may represent the clustering of several households. This type of settlement was widespread not only on the chalkland of Wessex but over much of southern Britain and can therefore be regarded as a type-site representing a particular kind of socio-economic structure (Cunliffe 2000, 167-70).

Figure 12.4 Gussage All Saints, Dorset from the air (photograph: Geoffrey Wainwright).

The recent series of large-scale excavations have, however, shown something of the complexities of the picture. The actual enclosure, so dominant in the archaeological record, may have been a feature of transitory significance, dug to define a settlement area at one moment and maintained or abandoned as the settlement developed. What does stand out is the fact that once a location had been chosen for settlement, sometimes as early as the eighth to sixth centuries BC, occupation often continued throughout the Iron Age with no recognizable break, implying a remarkable degree of social stability.

‘Banjo’ enclosures (Figures 12.5 and 12.6)

A second type of earthwork-enclosed site, usually about 0.2-0.4 ha in extent, occurs in Wessex, the Cotswolds and sporadically elsewhere (Perry 1966, 1970). Characteristically these sites are provided with a single entrance, to which runs a roadway defined on either side by V-shaped ditches about 1 m deep. Frequently the roadway joins a linear ditch at right angles at a distance of between 45 m and 90 m from the enclosure. At Blagden Copse, Hants, a limited excavation undertaken at the junction of the road ditches and the linear ditch showed that the two features had been planned in relation to each other and were therefore broadly contemporary.

Figure 12.5 ‘Banjo’ enclosures in Hampshire, drawn from air photography (sources: Perry 1966, 1970).

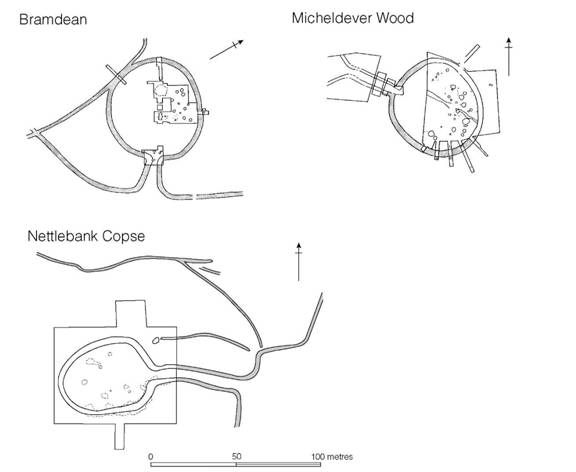

Figure 12.6 Excavated ‘banjo’ enclosures in Hampshire (sources: Bramdean, Perry 1982, 1986; Michel- dever Wood, Fasham 1987; Nettlebank Copse, Cunliffe and Poole 2000e).

Although ‘banjos’ are usually found separately there are a number of occasions in which two are found in close proximity, and some where two are actually conjoined by linear earthworks implying contemporaneity. Such sites are referred to as ‘spectacle’ sites. Overall the planning and setting of banjo enclosures strongly suggest that they were designed, at least in part, to aid the collection, selection and temporary corralling of livestock.

Four Hampshire ‘banjo’ enclosures have been excavated, Bramdean, Micheldever Wood and Owslebury in part, and Nettlebank Copse in total. Evidence of function is ambiguous. At Nettle- bank Copse the enclosing ditch was dug at the beginning of the Middle Iron Age to surround the site of a small abandoned farmstead. There is no evidence of any domestic structures inside contemporary with it, but in the first century BC, after the ditch had been partially cleared out for the last time, occupation debris was dumped into it on a number of occasions. The absence of internal structures and the nature of the deposits of debris are best explained by suggesting that the enclosure may have had a ritual function associated with the annual round-up of livestock accompanied by bouts of communal feasting. At Micheldever Wood, which was two-thirds excavated, the central area was kept clear but storage pits seem to have been arranged around the periphery and much the same pattern was noted at Bramdean. If the storage pits are contemporary with the enclosure ditches at Bramdean and Micheldever Wood then they must differ functionally from Nettlebank Copse, but the possibility remains that the pits relate to an earlier phase of occupation. At any event the small size of the enclosures, 40-50 m across, the long corridor approach and the long linear ditches which open out from the corridor strongly suggest a use which involves the rounding up of livestock. There would be nothing incongruous in supposing that some of the banjos may also have been occupied, though perhaps on a temporary basis.

Chronologically the banjos belong to the Middle and Late Iron Age and are thus a late addition to the landscape, occupying areas between the larger settlements already established in the earlier centuries of the Iron Age. Many of them would appear to occupy more marginal areas, which would be consistent with a use in animal husbandry.

Open settlements

Enclosed settlements of Little Woodbury and banjo type have received considerable attention from archaeologists largely because they are evident from the air as major landscape features, though they may be almost invisible from the ground. Two excavations of enclosures have, however, accidentally focused on a different problem - that of the unenclosed settlement. One of these, Winnall Down, has already been referred to (p. 243). Here a considerable Middle Iron Age settlement developed with little reference to an earlier enclosed settlement. The second site is Boscombe Down West, Wilts., where occupation of Early and Middle Iron Age date extended over 6.5 ha: the site was only recognized because a double-ditched enclosure had been constructed in the first century AD. In fact unenclosed settlements of considerable size are not at all uncommon. In the ninth to seventh centuries All Cannings Cross and Potterne, Wilts., are two well-known examples while in the sixth and fifth centuries we may cite Boscombe Down West, Wilts., Slonk Hill, Sussex, and the unenclosed phase of Bishopstone, Sussex. Boscombe Down West continued in use into the Middle Iron Age, at which time, as we have seen, the Winnall settlement outgrew its enclosure. These seven sites spanning the Iron Age are probably only the tip of the iceberg and provide a salutary reminder of the potential complexity of the settlement pattern.

Potterne and probably All Cannings Cross, together with East Chisenbury, Wilts., belong to a distinct type of open settlement characterized by the massive build-up of midden material composed of domestic rubbish and animal waste. The Potterne midden covered an area of 3.5 ha and survives to a depth of 2 m while the East Chisenbury midden is up to 3 m deep though less extensive at some 2.5 ha. In neither case has it been possible to establish the exact context of the midden but the East Chisenbury deposit is thought to lie largely within, but overlapping, the bank and ditch of a large enclosure. A meticulous examination of a sample of the Potterne midden showed it to have accumulated over a period of some 500 years, from 1100-600 BC, as the result of penning livestock and adding domestic rubbish to the animal waste and bedding material. At the All Cannings Cross site the nature of the midden was not closely observed, but pits, post-holes and ovens were found cut into the underlying subsoil although many of these may post-date the original midden. Several other middens of broadly similar type have been identified in Wiltshire. Most seem to have begun by the ninth century and to have continued to accumulate throughout the Early All Cannings Cross phase to the beginning of the sixth century BC. The question of their economic role will be considered again later (pp. 424-5).

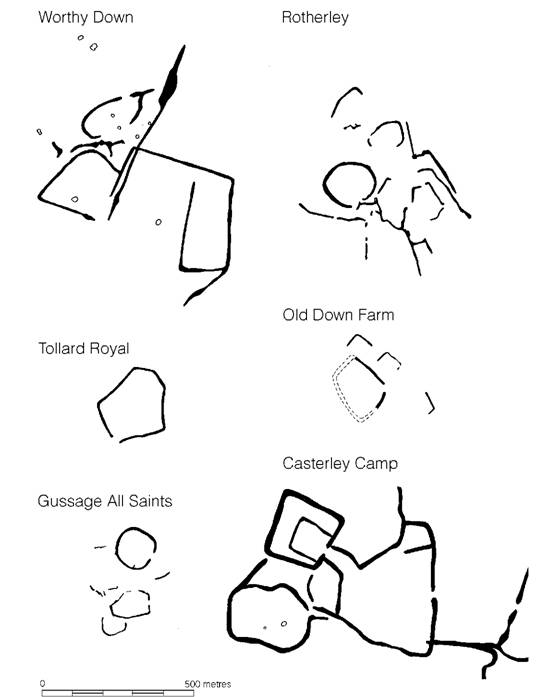

Ditched enclosures of the first century BC and first century AD (Figure 12.7)

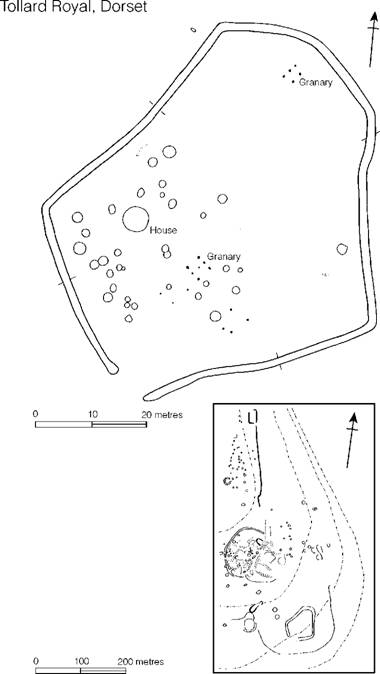

The tradition of surrounding farmsteads with a simple enclosing ditch was maintained in some areas of the south, notably Dorset, into the first century AD. The classic example of such a settlement is Tollard Royal in Cranborne Chase, Wilts., where total excavation has exposed the complete ground plan of the farm (Figures 12.8 and 12.9), consisting of a kite-shaped ditched enclosure of about 0.5 ha in extent, provided with a single entrance. Inside were found a single hut, thirty-five storage pits of varying capacity and three or four granaries. One of the most impressive features of the plan is the large open area within the enclosure, where presumably flocks and herds could have been temporarily corralled. The basic plan, clearly a direct continuation of the traditional Little Woodbury type, is further reflected in the neighbouring settlements of Rotherley and Woodcuts, which continued in use little changed well into the Roman period, and in the latest phase at Gussage All Saints and Old Down Farm (Figure 12.4).

A rather more extensive type of settlement, found sporadically in the south, is represented by the Wessex examples of Worthy Down and Owslebury, Hants, and Casterley Camp, Wilts. (Figure 12.7). All three sites are characterized by a complex series of ditches which define enclosures of varying sizes and shapes, some used for habitation, some (e.g. at Owslebury) for burial, others presumably for livestock. The plan of Casterley Camp is particularly informative for here it is possible to recognize the careful placing of entrances so as to allow maximum inter-use of enclosures. Such an arrangement would have been of value at those times during the year when flocks and herds needed to be brought together and sorted for culling, castrating or redistribution. The development of these complex ditched enclosures as an adjunct to settlements suggests the increased importance of stock rearing - a matter which will be returned to again later (p. 429).

Multiple ditch systems and enclosures

In parts of Wessex, particularly on the downland ridge between the rivers Wylye and Nadder, complex systems of ditches, sometimes multiple, are found associated with enclosures, often of banjo type. The best-known examples include Hanging Langford Camp, Hamshill Ditches, Ebsbury and Stockton Earthworks in Wiltshire and Gussage Hill in Dorset (Corney 1989). Where evidence is available these complexes seem to have flourished in the Late Iron Age, but may have begun earlier, and to have continued into the Roman period. They clearly represent a concentration of social effort and may therefore be communal foci of some kind, perhaps meeting places or even village settlements.

Figure 12.7 Ditched enclosures of the Late Iron Age (source: Cunliffe 1984c based on various sources).

Figure 12.8 Tollard Royal, Dorset (source: Wainwright 1968).

Figure 12.9 Tollard Royal, Dorset enclosure from the air (photograph: Dr J.K.S. St Joseph. Crown Copyright reserved).

Settlement size, status and siting

Many of the sites described above were single farming units. Little Woodbury, whatever its social implications, probably had only one centrally placed house in use at any one time (although the possibility remains that other contemporary huts may have been placed around the periphery of the enclosure). With its fine early house, 1.6 ha farmyard and considerable grain-storing capacity, it must have been the homestead of a wealthy man and his family. A short distance from the excavated site lay a far more substantial ditched enclosure, known as Great Woodbury (Figure 12.2), covering an area of about 4 ha and enclosed by a massive ditch of hillfort proportions some 6 m wide and 3.6 m deep. A single section through the ditch revealed pottery of saucepan pot type in the primary silting. While it would clearly be wrong to base too much on this limited evidence, it could well be argued that Great Woodbury replaced Little Woodbury. Certainly the relatively small percentage of saucepan pot wares from Little Woodbury would suggest that it ceased to be occupied fairly early in the period during which these types were commonly in use; moreover, it is hardly likely that the two sites were occupied at the same time.

By virtue of its non-defensive siting, Great Woodbury can hardly be regarded as a hillfort, but it may well represent a stage in the social development of the owning family, moving from the old site to the new when wealth had increased sufficiently to allow a new building programme to be undertaken. If these speculations are correct, there is no need to suppose that the actual size of the homestead community had increased; a larger area enclosed and a more massive ditch need be nothing more than status symbols. Massive enclosures for apparently single homesteads are known elsewhere as, for example, at Pimperne Down, where the large house was retained within a 4.7 ha enclosure. Thus size of enclosure does not necessarily reflect size of community: in many cases it may be dependent upon the status of the occupants.

A further indication of status is provided by artefacts which can be associated with aristocratic behaviour. At Gussage a bronze-smith was at work making a large number of horse-harness and chariot-fittings, presumably under the auspices of the owner. The product of this one craftsman would have been sufficient to deck out a considerable number of chariot teams, surely in excess of the needs of the particular community. It is possible, of course, that they were produced under the patronage of the owner who could then have used them as gifts to dependants, thus establishing or maintaining his superior status. The question is an intriguing but insoluble one. Articles of horse/chariot equipment occur sporadically on other enclosure sites, like the pair of linchpins from Old Down Farm, suggesting that enclosed settlements of this kind may have been of ‘aristocratic’ status. The relationship of these to the open settlements and banjos is impossible to define and the whole question is bound up with the function of the contemporary hillforts.

The principal difference between the settlements discussed here and hillforts is one of siting. Hillforts were always placed in defensive positions, usually on hill-tops or ridge-ends with good visibility and control of the main approaches: they were also, themselves, highly visible. Settlement sites, on the other hand, were chosen to be close to the arable land. Even the massive ditch of Great Woodbury cannot disguise the fact that the site has little tactical significance. The close relationship between settlement and arable land is demonstrated on a number of sites, but the Farley Mount enclosure in Hampshire is perhaps one of the more dramatic, showing many hectares of rectangular ‘Celtic’ fields spreading out regularly from the boundaries of the settlement. It is tempting here to think of both fields and settlement being laid out at the same time to colonize a piece of virgin downland.

It is difficult to generalize about the overall pattern of rural settlement but several regional surveys have now been published (Cunliffe 2000, 197-203). On the South Downs, in the area of Chalton, Hants, a detailed field study has shown a remarkable density of occupation sites, many of them sited by choice on the shoulders of east-facing slopes, linked to each other and to their fields by a network of trackways. In an area of 5 square km eleven settlements are known, some less than 0.5 km from their neighbours (Cunliffe 1974, figure 4). Such a density is not universal even on the chalk, for in a comparable survey of the Marlborough Downs based on the parishes of West Overton and Fyfield, only three settlements were found in a block of 12.9 square km, the average distance between them being 1.6 km.

An exhaustive survey of the evidence gleaned from aerial photography covering the area from the Test to the Bourne has provided a glimpse of the real complexity of the settlement evidence (Palmer 1984) but two well-defined patterns stand out (Cunliffe 1984a, figure 10.2). Around the hillfort of Quarley Hill the settlements cluster on a circumference about 1.5 km from the fort and at intervals of 1 km from each other, while to the south of Danebury strings of settlements line the flanks of the river Test and the Wallop Brook, spaced at intervals of about 1 km and sited at about the same distance from the valley bottoms. This latter group looks very much like a total pattern, with the landscape filled with farming units optimally sited to exploit the range of available resources. The Quarley grouping on the other hand, while packed at the same density, controlled a more limited range of resources in the immediate neighbourhoods. Most significantly the individual sites lacked easy access to well-watered meadow. Thus, either their subsistence regimes differed radically from those of the Danebury group or else the meadow environment was available to them through some mechanism which involved limited transhumance.

None of the figures given above can be regarded as of statistical value since the recognition of a site is conditioned by a number of chance factors, and however much the chances of discovery are increased by intensive fieldwork, as in the case of the examples quoted, without excavation there can be no assurance that all the sites were in use at the same time, nor is it possible to compare the sizes of individual settlements. That said it is now tolerably clear that on favoured land, like the chalk downs, substantial farms were closely spaced.

The Cotswolds and the Upper Thames valley

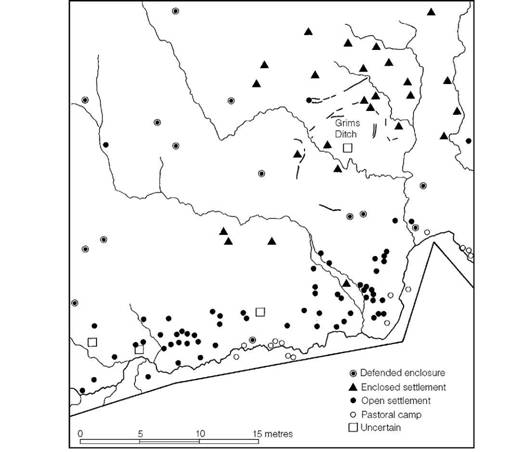

The Upper Thames valley is one of the most systematically explored Iron Age landscapes in Britain thanks almost entirely to the work of the Oxford Archaeological Unit initiated in 1973, now Oxford Archaeology (Hingley and Miles 1984; Miles 1998). The complexity of the landscape was first demonstrated as the result of a systematic survey of the air photographic cover (Benson and Miles 1974), since when a carefully controlled programme of large-scale excavation has been in operation. It is now possible to stand back from the detail to see a clear pattern emerge (Figure 12.10).

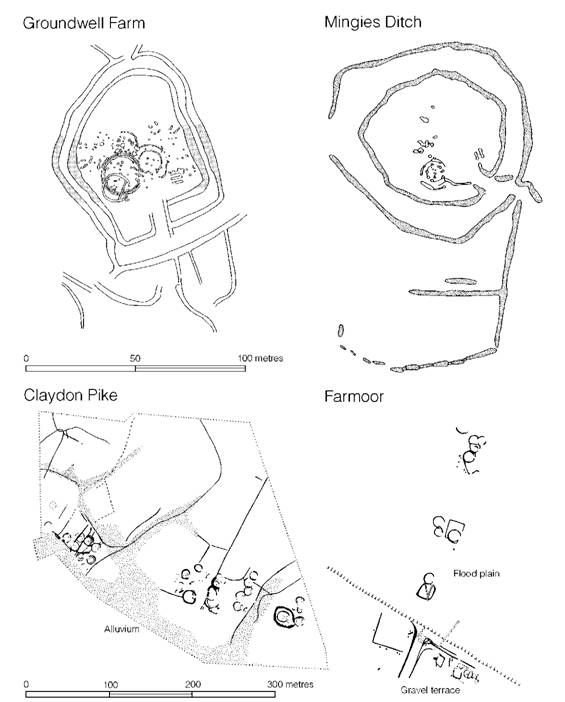

Three distinct geographical zones can be defined - the Cotswold flanks, the gravel terraces and the river flood plain - and each has its own type of settlement. On the Cotswold dip slope, cut by the tributaries of the Thames, small enclosed settlements prevail. In plan at least, these have much in common with the banjo enclosures of the Wessex chalk (Darvill and Hingley 1982) but excavation has been minimal and there is little yet to say of them. Hingley (1984b) has, however, suggested that they represent individual farms each with their own distinct territories. The excavation of part of a ditched enclosure of Middle Iron Age date at Guiting Power, Glos., in the heart of the Cotswolds, gives some idea of what can be expected: the dense scatter of pits and post-holes is not unlike a typical Wessex enclosed settlement. Rescue excavation during road schemes has produced further comparable evidence. Near Birdlip, Glos., rectilinear ditched enclosures of the Middle-Late Iron Age were discovered associated with large numbers of storage pits. One of the enclosures contained a large circular building. It is now at last possible to begin to characterize the nature of settlement spreading along the Cotswold ridge (Parry 1999, 52-7). To the south of the Thames, 5 km north of Swindon, at Groundwell Farm, a ditched enclosure, superficially of banjo form, was examined (Figure 12.11). The pottery, which is closely similar to that of the Upper Thames basin, suggests that occupation began in the fifth century and continued to the third century or later, during which time a succession of houses were built, together with post-built storage structures. We are clearly dealing here with a single family unit, practising mixed agriculture, occupying the same site for many generations. Groundwell Farm may well be typical of the enclosed settlements of the upland areas and provides a salutary warning that the superficial resemblance in plan to the banjo enclosures of Wessex should not be taken to imply a similarity of socio-economic function.

In contrast to the hill sites, the settlements of the gravel terraces are far better known from a series of large-scale excavations. On present evidence it seems that two different social units can be recognized. On the first gravel terrace the settlements are of extended family or hamlet type. Examples of the first include Watkins Farm, Northmoor, and Mingies Ditch (Figure 12.11). At Watkins Farm a settlement was established on a dry hillock of gravel some time in the Middle Iron Age. It consisted of no more than two contemporary houses and ancillary storage structures, which were rebuilt on at least five occasions, enclosed within a double-ditched system with external antennae ditches. The two enclosing ditches were probably designed to provide corral space between for animals. Environmental studies have suggested that the settlement was set in a landscape predominantly of grassland. Mingies Ditch is clearly a settlement of family or extended family size, though whether the enclosure formed the sole residence of the family or was only occupied seasonally is unclear. Watkins Farm was comparable in extent and complexity, and remained in use throughout the Middle and Late Iron Age.

Figure 12.10 Settlement distribution in the Upper Thames valley (source: Hingley and Miles 1984).

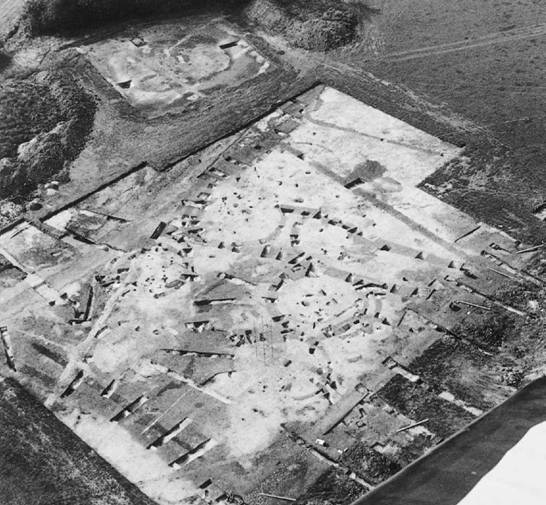

A more complicated pattern is presented by the Middle Iron Age settlement at Claydon Pike, near Lechlade (Figures 12.11 and 12.12). Here three distinct gravel rises, separated by wetland, were in occupation, each producing evidence of a complex sequence of houses. In the case of the western ‘island’, where the sequence could be worked out in detail, it is clear that only two or three houses were in contemporary use. Thus each ‘island’ was probably the homestead of a single family. If all three were in occupation at one time then the settlement is best regarded as a hamlet.

Figure 12.11 Settlements in the Upper Thames valley (sources: Groundwell Farm, Gingell 1982; Mingies Ditch, Allen and Robinson 1979; Claydon Pike, Miles and Palmer 1982; Farmoor, Lambrick and Robinson 1979).

Figure 12.12 Claydon Pike, Lechlade, Glos. View of Middle Iron Age roundhouse sites on an ‘island’ of gravel bounded by drainage ditches (photograph: Oxford Archaeological Unit).

The second gravel terrace is dominated by a different type of settlement typified by those excavated at Ashville and Gravelly Guy (Figure 12.13). Both cover many hectares, within which a distinct zoning is apparent, with the settlement and pit storage areas kept quite separate throughout much of the life of the settlement. This type of arrangement is well known at a number of second terrace sites (Hingley and Miles 1984, 62-3) and the very considerable grain storage capacity which they exhibit may suggest that sites of this kind performed centralized storage and redistribution functions for the larger community.

Finally, a number of sites are known on the flood plain itself: of these Farmoor provides a well-excavated example (Figure 12.11). Here three separate groups of houses and attached enclosures were discovered spaced at intervals of about 50 m across the meadow. Each was sufficient to house a single family, but since all flood plain sites would have been under water for much of the winter they presumably represent summer steadings providing shelter for the family, or that part of it, who came to the meadows with the flocks and herds. During the winter months they and their stock would have rejoined the rest of the community at the larger settlements on the first or second terrace.

Figure 12.13 Gravelly Guy, Stanton Harcourt, Oxon. Middle Iron Age farm with over 600 storage pits. The rectilinear enclosures are Roman (photograph: Oxford Archaeological Unit).

From what has been said above it is tempting to see the complex of valley settlements on the gravel terraces and flood plain as part of a single socio-economic system operating a subsistence strategy based on the exploitation of a number of discrete ecological zones. Such a system would have required co-operation which would have encouraged the growth of larger settlement agglomerations. The limestone hill sites, on the other hand, could well have been self-contained units exploiting the range of rich soils in their hinterlands. Thus two entirely different social systems may have emerged in the region by the Middle Iron Age (Hingley 1984b).

Viewed against the perspective of time, the Middle Iron Age seems to have been a period of population expansion, colonization and consolidation. From the beginning of the first century BC onwards further changes can be detected: a more organized landscape now develops, with trackways and rectangular paddocks laid out, sometimes impinging upon earlier, more scattered, settlements (Hingley and Miles 1984, 65). This is particularly apparent at Claydon Pike where a large new settlement complex replaced the Middle Iron Age homesteads. As part of this pattern of change a new type of settlement appears, typified by Barton Court Farm where a farm, enclosed in a rectangular ditched enclosure, was established at the beginning of a sequence which led eventually to the development of a small Roman villa. The details of these changes are still rather ill-focused but the evidence is consistent with a continuing population rise and the emergence of a more integrated trading network, occasioned by the increased demands of the Roman world, in the century or so before the conquest.

The Severn–Avon valleys and the west Midlands

Our detailed knowledge of the settlements of the Upper Thames valley is based on a tradition of intensive fieldwork and excavation. Had equivalent effort been put into the archaeology of the Avon valley, to the west of the scarp slope of the Cotswolds, it is not at all unlikely that a similar pattern would have emerged. As it is we have only glimpses of the richness of the data through surveys (Webster and Hobley 1965; Oswald 1969; Hingley 1989), through the large-scale excavations at Barford and Beckford, Warks., and from a number of other sites, sampled mostly during rescue excavations, which are gradually filling out the picture (Ray 2001; Palmer 2001).

At Beckford, close to Bredon Hill Camp, a sufficient area has been examined to show that the settlement was extensive and consisted of a series of large ditched enclosures which had been refurbished on a number of occasions. Within each enclosure, settlement structures consisting of smaller ditched enclosures, circular huts with drip gullies around them, four-post ‘granaries’, cobbled yards and storage pits were found in abundance, together with artefacts representing all the normal farmyard activities, as well as bronze casting. The extensive nature of the remains would suggest that the Beckford settlement was a village of some size: it is possible that each of the large enclosures represented the holding of a single family unit. The complex has similarities to those found on the second terrace of the Upper Thames but how it fitted into the regional system of the Avon is at present ill-defined and will remain so until more sites are excavated in the general vicinity.

Park Farm, Barford, Warks., sited on a gravel terrace of the Avon, is an example of a more contained settlement of single family size. It comprised a rectangular enclosure containing two circular houses and a penannular drainage gully defining an open area thought possibly to be an animal pen. The enclosure was set out in relation to a linear boundary ditch of probable Late Bronze Age date, the existence of which was evidently still remembered in the Middle Iron Age when the enclosure ditch was dug. Occupation appears to have been fairly short-lived. Park Farm is only one element in a highly complex pattern of settlement and land use which can be traced all along the course of the Avon hereabouts. Aerial photography and fieldwork have shown that each micro-region defined by a loop of the river contains a settlement complex, the most easily identifiable features of which are rectangular ditched enclosures comparable to Park Farm (Crackwell and Hingley 1994, figure 1). The implication is of a densely settled river valley.

Hingley’s detailed survey of the evidence from central and southern Warwickshire (1989, 1996) offers the first serious attempt to consider the available evidence in terms of regional systems. Its potential is considerable, but without a concerted input of carefully designed excavations, of the kind mounted in the Upper Thames valley, few significant advances in understanding will be possible. That said, regional differences and similarities are beginning to appear. The clearest aspect is that the settlement pattern in the Avon valley, with its banked and ditched enclosures representing individual farmsteads, is more comparable to that of the Ouse and Nene valleys than to the Upper Thames where open settlements are more common.

The Severn estuary region presents a very different landscape and a range of varied resource potentials, of which the most extensive are the alluvial tracts flanking the estuary (Rippon 1997). Work at Goldcliff on the Gwent Levels has recovered a number of rectangular timber structures and a trackway built within a zone of freshwater peat land subject to periodic flooding. The function of the structures is unclear but they may be stock pens reflecting seasonal grazing regimes. On the eastern side of the estuary - the area of the Avonmouth and Gloucestershire Levels - two settlements have been examined, at Hallen and Northwick, Avon. Both are of Middle Iron Age date but were short-lived and seasonally occupied, presumably to exploit the rich summer grazing which the levels had to offer (Gardener et al. 2002). The evidence, therefore, would seem to suggest that the settlements on the levels were part of a system of transhumance which would have involved one segment of the population leaving the upland settlements to tend the flocks and herds on their summer pastures flanking the estuary.

The west Midlands

The triangle of country west of the Avon-Soar-Trent, east of the Severn-Dee and south of the Pennines is composed of vast tracts of Keuper marl, Triassic sandstones and coal-measure shales, highly unconducive to pre-Roman Iron Age settlement. Apart from the river gravels and the more fertile sandstone and limestone hills, much of the area appears, on present evidence, to have been largely unsettled.

Of the few hillforts known in the area the only site to have been excavated in any detail is Breedon-on-the-Hill, Leics., sited on a hill of magnesian limestone overlooking the valleys of the Soar and Trent. No internal buildings were recognized, but occupation appears to have been extensive. Pits, possibly for storage, and a number of quernstones suggest that grain production was widely practised. The quantity of animal bones recovered was not large but cattle were numerically more common than sheep (50 per cent compared with 36 per cent of all animal bone), underlining the importance of the pastures along the Soar valley. The use of sheep as wool producers is, however, reflected in the discovery of a weaving comb.

Largely as the result of extensive programmes of aerial photography it is now known that the river gravels of the west Midlands were as densely occupied as those of the south and east Midlands. One of the most comprehensively studied regions is the valley of the Tame (Smith 1977, 1978a) but only at Fisherwick has excavation on a reasonable scale been carried out and published. Here a Middle Iron Age enclosure of some 0.25 ha, containing evidence of at least two circular houses, was partially examined. The enclosure was part of an organized landscape, divided by drainage ditches, which included several other enclosures. Environmental evidence suggests that the fields in the immediate neighbourhood may have served largely for stock rearing but there is ample evidence of cereal production from occupation levels associated with the settlement.

The east Midlands, the fen edge and East Anglia

Until the mid-1960s the Midland river valleys and the Jurassic limestones and clays were largely devoid of recorded Iron Age settlements, with the exception of the regions in the immediate vicinity of Oxford (OS 1962). Intensified aerial survey combined with a number of excavations in advance of gravel and ironstone extraction and building programmes, together with a tradition of high-quality fieldwork, however, has totally altered the picture. Far from being sparsely occupied the Midlands can now be shown to have been exceptionally densely populated (Hall and Hutchings 1972; Knight 1984; Pryor 1984, 230-40). Moreover it has become clear that, during the Iron Age, communities had begun to spread from the lighter soils of the limestone and gravel on to clay land which had previously been thought to be totally unsuitable for prehistoric settlement. A number of regional overviews usefully bring together the scattered evidence for Leicestershire (Liddell 1982; Clay 2001), Bedfordshire (Dyer 1996a), East Anglia (Davies and Williamson 1999) and the Fen region (Hall and Coles 1994).

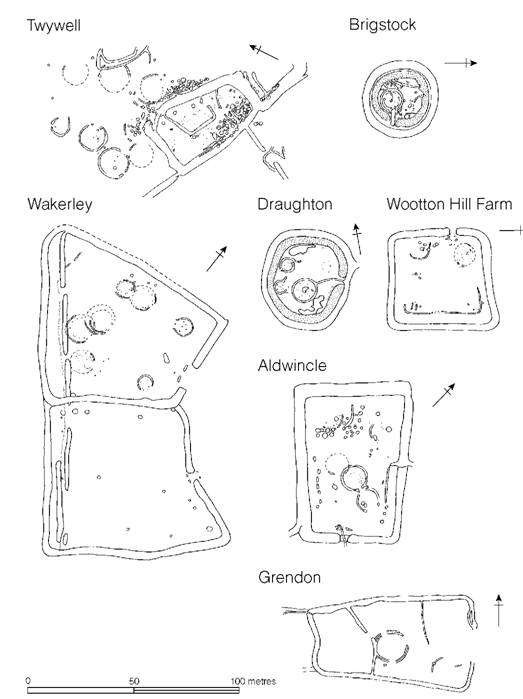

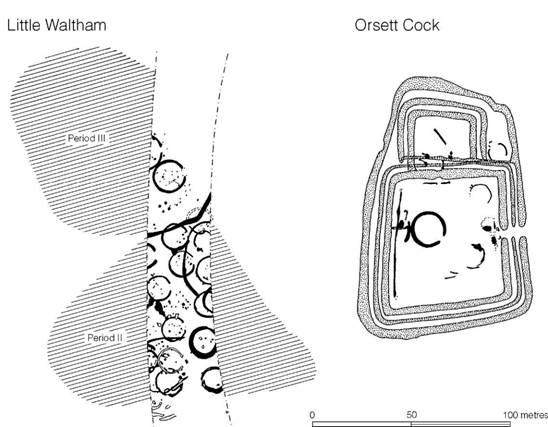

One of the most thoroughly studied regions is Northamptonshire. Many settlements have now been partially or extensively excavated. Of these Twywell, situated on the limestone uplands of Northamptonshire, provides an example of a complex habitation site dating to the period from approximately the fourth to the second century (Figure 12.14). The site consisted of a number of ditched enclosures of which one, only 0.1 ha in area, was totally excavated. Its development was complex, the ditch, averaging 3.7 m wide and 1.22 m deep, having been recut on several occasions. Evidence of structures, in the form of pits, post-holes and drainage gullies, was not restricted to the enclosed area, but spread densely outside; indeed it would appear that the huts had been sited so as to line the approach road leading to the enclosure entrance, but contemporaneity was difficult to prove. The evidence of Twywell therefore shows that ditched enclosures form only one element in otherwise more extensive settlement complexes. It may be compared to the contemporary sites of Abingdon and Beckford.

A number of discrete enclosures, unencumbered by neighbouring structures, are known. At Blackthorn, Northants, a double-ditched enclosure of about 0.1 ha, dating to the second or first century BC, was found to contain a single house together with twenty-eight pits, some of which could well have been for grain storage. Three kilometres away at Moulton Park a contemporary, but larger, enclosure was found to protect several houses. Here, however, occupation continued into the first century AD as the settlement spread away from its original nucleus. Other Northamptonshire rectangular enclosures excavated on a large scale include Wootton Farm and Grendon Quarry. Clearly this type of settlement unit is widespread in the region. A rather different settlement type is presented by the excavations at Draughton and Brigstock, Northants (Figure 12.14). At Draughton, a ditched enclosure 30 m across was found enclosing three houses, not necessarily contemporary, ranging in diameter from 5.8 to 10.4 m, the largest presumably being the principal house. A similar settlement was excavated at Brigstock, where the enclosure was 22 m in internal diameter, and protected a single house 7.8 m in diameter set in a penannular drainage ditch and with a stone-built pathway leading from its door to the enclosure entrance. The enclosure excavated at Brigstock is only one element of a complex settlement pattern revealed by air photography. The selection of single houses (or homesteads) for enclosure in this monumental way can only reasonably be explained in terms of the exceptional status of the owners.

Further south, in the valleys of the Ouse and Cam and adjacent areas, a large number of rescue excavations, mostly partial, are now beginning to add detail to the settlement pattern, showing yet again that, from the Middle Iron Age, settlement seems to have been expanding. Complex ditched enclosures reflecting use over a period of time have been examined at Norse Road, Bedford, Flitwick, Beds., and Edix Hill, Barrington, Cambs., but the limited scale of the excavations at present limits useful generalizations. A more unusual type of site is represented by the circular ditched enclosure of Arbury Camp, Cambs., which covers some 5 ha and is comparable in form and size to hillforts, differing only in its location on a low-lying gravel terrace. Limited sampling inside failed to identify any significant trace of occupation. It is tempting to believe that such an unusual structure served as a focal point for an extensive social territory.

Figure 12.14 Settlements in the east Midlands (sources: Twywell, Jackson 1975; Brigstock, Jackson 1983; Wakerley, Jackson 1978; Draughton, Grimes 1961; Aldwincle, Jackson 1977; Grendon, Jackson 1996;

Throughout the east Midlands the tradition of enclosing the principal settlement area with a ditch and presumably a bank continued into the late first century BC and early first century AD. An example of this later type of settlement is provided by Colsterworth, Lincs. (Figure 12.15), which consisted of a ditched enclosure measuring 73 by 64 m, containing two clusters of huts of varying dates, the largest being some 13.4 m in diameter. At the broadly contemporary site at Tallington, in the Welland valley, a rectangular ditched enclosure 65.5 by 48.8 m lying alongside a trackway was totally excavated, revealing most of the structures appropriate to a farming community with the exception of the house (quarried away?), and grain storage pits which would have been impossible to construct in the wet gravelly soil; grain must therefore have been stored in above-ground containers. An enclosure of the same date and closely similar size, excavated at Orton Longueville, Northants, provides interesting evidence for the continuity of socio-economic units of this size well into the Roman period.

Not all of the Late Iron Age settlements in the east Midlands were simple ditched enclosures: more complex forms developed and many can now be recognized as the result of aerial photography. The later stages of the settlement at Moulton Park, Northants, and the partially excavated site at Hardingstone, Northants, clearly belong to this category as do several of the settlements examined in Bedfordshire. The evidence at present available would therefore suggest that here, as in the south, simple and complex ditched enclosures continued to be constructed side by side up to the time of the Roman Conquest.

In general terms, it can be said that in the east Midlands enclosures, usually but not invariably representing single family units, formed a recurring element in the settlement pattern from at least as early as the fourth century BC to the Roman Conquest and later. Where the subsoil was suitable storage pits were dug, but elsewhere, on the gravels and on the clay land, grain must have been stored above ground. On present evidence it would seem that the enclosed settlements of the Midlands were significantly smaller than the broadly contemporary Wessex sites of Little Woodbury type but are comparable to those of the west Midlands and East Anglia. This might suggest that the Little Woodbury type of settlement reflects a particular socio-economic system restricted to central southern Britain in the Early and Middle Iron Age. How the systems varied is a matter for further detailed investigation.

We have already seen that on the Wessex chalkland and in the Upper Thames valley large unenclosed settlements were not infrequent. These, it has been suggested, may represent large agglomerations of people living together in hamlets or villages. Evidence from Northamptonshire suggests that here too substantial unenclosed settlements are to be found. The spread of occupation at Twywell has already been mentioned and at Wakerley, Northants, ironstone quarrying has exposed a settlement in excess of 500 m in length, but given the absence of total excavation and bearing in mind the difficulties of assessing what is contemporary in such palimpsests (Knight 1984, 227-38) it would be rash to talk of villages rather than groupings of two or three family units.

In Lincolnshire a number of settlements grew to quite considerable proportions. Best known is Dragonby where the settlement of houses set in a complex of ditched enclosures eventually reached 8 ha in extent. Old Sleaford was of comparable complexity but its Iron Age extent is undefined. Both settlements were flourishing in the Late Iron Age, by which time they may have acquired many of the functions appropriate to urban settlement. Large settlement complexes of this kind are a feature of the Jurassic Zone of Lincolnshire in the Late Iron Age (May 1984).

Figure 12.15 Colsterworth, Lines. (source: Grimes 1961).

Within the east Midlands lies a rather specialized environment – the long sinuous fen edge where the dry land of Lincolnshire, Cambridgeshire and Norfolk met the vast expanse of waterlogged fen that fringed what is now the Wash, into which the rivers Ouse, Nene, Welland and Witham drain. The Fens have recently been studied in campaigns of systematic fieldwork, with the result that much has been learnt of the environmental changes to which the region has been subjected (Waller 1988; Hall and Coles 1994) and the settlement patterns of successive periods including the Iron Age are now becoming much more clearly focused (Simmons 1980; Hall 1981, 1987; Lane 1988). Large-scale excavations of fen-edge settlements of Iron Age date are at present few but four sites of outstanding interest show something of the complexity of the problem: Fengate, Northants, Upper Delphs, Haddenham, Wardy Hill, Coveney, Cambs., and Tattershall Thorpe, Lincs.

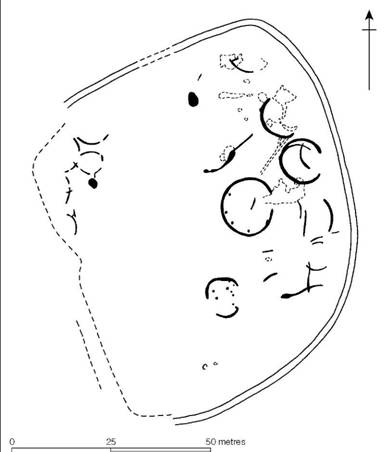

Fengate is a complex open settlement of considerable extent comprising a series of ditched enclosures or paddocks associated with at least eighteen circular houses, a few pits and isolated post-holes (Figure 12.16). The size and longevity of the settlement, which was occupied throughout much of the Iron Age, suggests a stable economic system based, presumably, upon the exploitation of the clay and limestones of the dry land to the west and the varied resources of the fen to the east.

Figure 12.16 Contrasting fen-edge settlements (sources: Fengate, Pryor 1978; Haddenham, Evans and Ser- jeantson 1988; Wardy Hill, Coveney, E. Evans 1992).

Much the same resource potential attracted a small community to colonize a gravel spread on the edge of the fen at Upper Delphs, Haddenham, where boundary ditches and enclosures have been traced over about 5 ha. One element in this complex, on excavation, proved to be a succession from open settlement to enclosure (Figure 12.16). In the open phase, at least two contemporary houses were associated with fields (or cross-ploughed plots). This was succeeded by a ditched enclosure containing a substantial circular house which was later replaced by two houses, the enclosure ditch continuing to function. The sequence suggests a well-established community, possibly of single family size, while the environmental evidence would support the view that occupation was year round. A site of broadly comparable size and form to Upper Delphs was totally excavated at Wardy Hill, Coveney, at the marsh edge on the north side of the Isle of Ely (Figure 12.16). The settlement was enclosed by a ditch and rampart while the entrance seems to have been defended by a series of outwork ditches. Inside were four circular houses arranged in two pairs which were thought not to be contemporary. The settlement seems to have been occupied from the Middle Iron Age into the early decades of the first century AD, and to judge by the quantity of finds the excavator considered it to have been of high status.

Tattershall Thorpe, Lincs., is altogether different in form and presumably function. It is represented now by a substantial double-ditched enclosure, roughly oval in shape, situated on a gravel rise 5 km from the fen edge. The nature of the internal occupation is unknown but the ditches have been sampled, providing valuable environmental evidence pointing to intensive stock raising. The site would be well suited as a corral for controlling flocks and herds at certain times during the year while the wetlands to the south would have provided admirable summer grazing. It is tempting to see some such system in operation but until the interior of the enclosure is sampled the complexities of the subsistence regime will remain obscure.

The fen edge is clearly an environment of some considerable interest for Iron Age studies, not least because the survival of organic material holds out the possibility of examining the subtleties of the subsistence economy. Settlements occupying the interface between wetland and dry-land resources provide a key to understanding how regional systems work, since they controlled the production of a range of marshland resources some of which may have been desired by the dryland communities of the interior. By studying the processes of exploitation and transmission significant advances in our understanding of Iron Age society are within reach.

East Anglia is still something of an unknown from the point of view of settlement morphology. That said, the care with which the archaeological record has been gathered and curated over recent years has allowed the preparation of distribution maps of material culture which clearly demonstrate a high density of activity during the Iron Age (Davies 1996). A limited number of small rectangular enclosures have been identified as well as the better-known larger earthwork enclosures of hillfort proportions (Davies et al. 1991). The overall impression given is that settlements were extensive but were, for the most part, unenclosed. Without enclosing ditches they are less likely to be identified on air photographs.

Finally, to questions of population: extensive field surveys carried out in recent years, especially in Northamptonshire, are revolutionizing our ideas of settlement pattern and necessarily reflect on estimates of population. Until a quantitative assessment is made firm conclusions cannot be attempted, but it is clear even now that by the third century BC much, if not most, of the river gravel area was settled to capacity and in eastern Northamptonshire settlement was already spreading on to heavy clay land. Exactly the same phenomenon has been recognized in East Anglia, where the Middle Iron Age saw an expansion from the lighter soils of the west on to the boulder clays of the central area. To what extent this phenomenon represents the result of a rapid increase in population in the fourth or third century is a problem to be resolved by future fieldwork and excavation, but even on present showing, by the Middle Iron Age the population of the east Midlands and East Anglia must have been similar in density to that of the chalkland of the south.

The Lower Thames basin

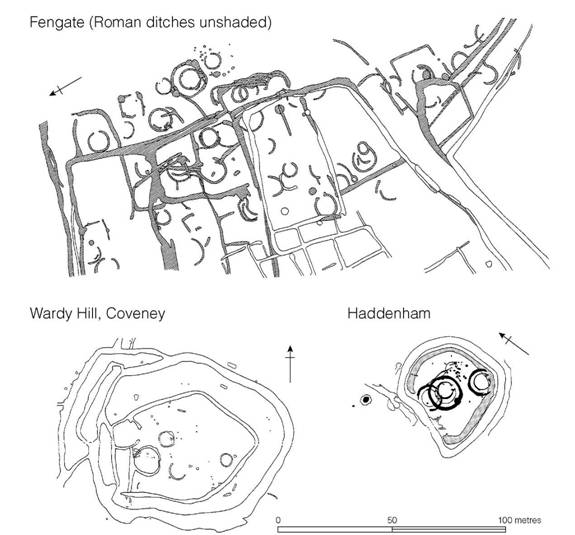

The triangle of land fringed by the Chilterns and the North Downs and dominated by the estuary and lower valley of the river Thames has produced comparatively little good evidence of settlement apart from a number of casual observations and the results of limited excavation. But the few large-scale excavations that are available for assessment are of considerable interest and show the potential richness of the record. At Little Waltham, Essex, a straggling settlement of circular houses, extending for 200 m along the terrace flanking the flood plain of the river Chelmer, is hardly likely to represent less than a hamlet or small village of the Early–Middle Iron Age (Figure 12.17). This is in marked contrast to the strongly defended homestead of Late Iron Age date found at Orsett, commanding the lower reaches of the Thames (Figure 12.17), or the small farm at Farningham Hill in the Darenth valley in Kent, 12 km upstream from the Thames, where a modest house, together with a few storage pits, was set within a comparatively slight ditched enclosure. These three examples, together with a few other large-scale excavations (e.g. Gun Hill and Mucking), suggest that the settlement types of the Thames basin conform to the general range found elsewhere in the south-east but are yet too few to warrant a more detailed regional assessment.

The Somerset Levels

The expanse of wetland between the Mendips and the Quantock hills is of considerable archaeological potential but it is only since about 1960 that it has been systematically explored in advance of intensified peat cutting and the lowering of the water table (B. and J. Coles 1986). The best-known area lies between the Polden hills and the Wedmore ridge and includes the two famous Iron Age settlements of Glastonbury and Meare: Glastonbury was almost entirely excavated between 1892 and 1907 by Bulleid and Gray while Meare, consisting of two separate sites, was partially excavated by the same team from 1908 to 1956 and by Michael Avery from 1966-9. In 1978 the Somerset Levels project began a systematic re-examination of both villages. The literature is extensive (site list, pp. 661, 665) but the clearest and most authoritative overview of the sites in their regional context is provided by Bryony and John Coles (1986, 153-83) while the details of the two lake villages are summarized by Minnitt and Coles (1996).

Glastonbury can fairly be regarded as a ‘lake village’ in that it was built on a morass, in an area of the Levels where water was prevalent, on an artificial foundation of brushwood and larger timber packed with bracken, rubble and clay. Upon this foundation up to eighty circular buildings had been constructed during the Middle and Late Iron Age (Figure 12.18). The settlement, roughly triangular in shape, was surrounded by a timber palisade, more to retain the artificial island than to provide a defensive enclosure. The circular buildings varied in size and construction. The larger and more elaborate had walls of vertical timbers supporting wattle and daub, and successive floors of clay usually with a hearth in the centre. The door frames were frequently carefully constructed, often with a porch. By no means all of the circular structures conformed to this type: some were without recognizable walls and others without hearths. The particular interest of the site focuses upon the possibility it offers of reconstructing social groupings within the settlement. Assuming that different types of circular building performed different functions, for example for living and sleeping, cooking, storage, weaving, etc., it ought in theory to be possible to define the grouping of structures which a single extended family might inhabit.

Figure 12.17 Settlements of the Lower Thames basin (sources: Little Waltham, Drury 1978; Orsett Cock, Carter 1998).

An attempt to do this by D.L. Clarke (1972) raised expectations but under critical analysis has been found wanting (B. and J. Coles 1986, 164-71; Barrett 1987). This does not mean, however, that the general approach is invalid and a detailed reassessment is still possible. One thing is clear - the eighty or so circular houses identified in the excavation would have represented many stages of rebuilding during the life of the village, which is thought to have lasted from c. 250 to 50 BC. Rebuilding would have been a continuous process but few snapshots of the village can be offered (Minnitt and Coles 1996, 19-22). The initial settlement of c. 250 BC consisted of five or six houses and some spreads of clay laid to provide space and stability for open air activities. Fences provided windbreaks and were used to protect the edges of the clay spreads. The village at this stage could have accommodated about four extended families numbering some fifty people in all. Within a few decades the settlement grew. New clay spreads were laid, seven more houses were erected and a landing stage was built for boats. By the end of this phase the community may have grown to about 125. Expansion continued after 150 BC, the settlement eventually reaching its maximum size of fourteen or fifteen families making a community of some 200 souls in all. All this time building and renovation were continuing: the enclosing fence was enhanced and new pathways laid out. By 100 BC the settlement was at its peak but, as the water table began to rise, decline set in and within fifty years the site was completely abandoned. The rising water which brought the village to an end was the very reason that so much of the organic component of the material culture was preserved in such a remarkable condition.

Figure 12.18 Glastonbury, Somerset (sources: Coles and Coles 1986; Coles and Minnitt 1995).

The two ‘villages’ of Meare were altogether different. They comprise two separate elongated clusters of mounds, 60 m apart, built on the edge of a raised bog without any form of brushwood foundation. The individual mounds, like those of Glastonbury, were built of superimposed clay floors, usually with central hearths which were replaced more often than the floors. Very little evidence was found of superstructures, a fact which has led to the conclusion that the buildings were flimsy and perhaps little more than tents. This does not, however, mean that the settlement was impoverished. The artefacts recovered are impressive in both quality and quantity and there is ample evidence for a range of activities being undertaken, including the manufacture of glass beads. John Coles has put forward the interesting hypothesis that the Meare ‘villages’ were a very specialized kind of site - the meeting-place of an annual ‘trade fair’ where people from considerable distances could assemble in peace to trade and exchange goods and to take part in a range of social, and perhaps religious, interactions. Such meetings form an essential component of European folk history and are still evident today in fairs, usually held on saints’ days on common land. The Meare site is well situated for intertribal meetings since it lies on the border between the Dobunni and the Durotriges.

Glastonbury and Meare represent two very different kinds of settlement but they are only a part of a far more complex socio-economic system which includes the extensive use of the Mendip caves and of an arc of hillforts which fringe the Levels. The details of the interrelationship of these various settlement elements have still to be worked out.

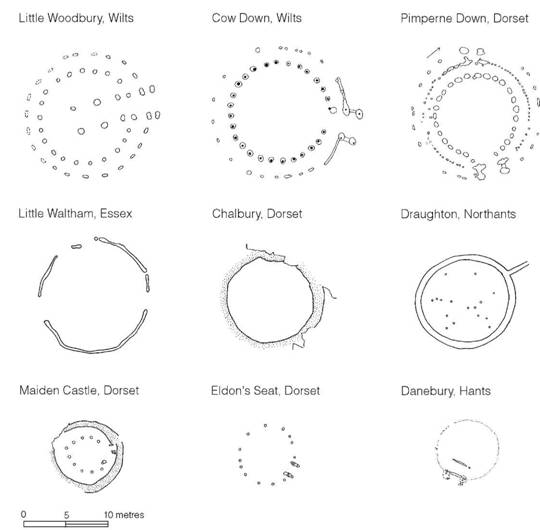

Houses (Figure 12.19)

Having considered the variety of settlement sites in the south and east of Britain something must now be said of the houses, or more accurately the circular buildings, within which the community lived and worked. Since more than a thousand house plans are now known, the brief discussion which follows can be little more than a broad overview.

Houses of the late second and early first millennia are now well known, principally from the excavation of the Sussex settlements. Characteristically they are simple circular structures averaging 6 m or so in diameter, constructed of a series of upright timbers placed somewhat irregularly in a circular or oval setting; central supports were seldom employed and indeed were not necessary for structures of such small span. Where huts have been terraced slightly into a sloping hillside, it is evident that the upright timbers did not form the outer wall of the hut but were simply supports for the sloping rafters, the lower ends of which probably rested on the outer edge of the terrace, which in some cases was up to 1.5 m away from the ring of vertical timbers. Thus two areas were created: a central area with a high roof-line where the principal activities of the house were carried out, and a surrounding area between the posts and the wall of the hut which could have served as storage or sleeping space. Approximate calculations for a small hut from Itford Hill, Sussex, show that 14 sq m were available for ‘living’ and 19 sq m for sleeping and storage (see Figure 3.8). Few of the early huts show any great refinement in structure but substantial door-posts and short porches are known.

This basic house type continued in use throughout the Iron Age (Guilbert 1981). The sequence at Eldon’s Seat (Encombe), Dorset, spanning the period from the eighth to the sixth century, shows a gradual increase in diameter from 6 m up to 9 m for the latest house. There was also a trend towards a more regular spacing of timbers and one hut was provided with an entrance porch. The latest house was very regularly constructed, and the spacing of the vertical posts in relation to the edge of its platform implies that they served not only as rafter supports but also as the wall timbers. A series of structures of comparable date were found within the hillfort of Winklebury, Hants, ranging in size from 8 to 12 m: most of them had short porches. Simple houses of this kind continued into the third or second century BC, for example house 2 at Little Woodbury, Wilts., which can be shown to belong to the Middle Iron Age (see Figure 12.2).

Figure 12.19 Plans of southern British houses (sources: Little Woodbury, Bersu 1940; Cow Down, S.C. Hawkes 1995; Pimperne Down, Harding, Blake and Reynolds 1993; Little Waltham, Drury 1978; Chalbury, Whitley 1943; Draughton, Grimes 1961; Maiden Castle, Wheeler 1943; Eldon’s Seat, Cunliffe 1968b; Danebury, Cunliffe 1984a).

In parallel to the tradition of simple ring-post houses, more complex structures developed. House 1 at Little Woodbury offers one of the clearest examples. Here two concentric circles of posts were erected, the inner circle being more massive and taking most of the weight of the roof timbers, the outer circle taking the slighter posts. The house is further complicated by the central setting of four timbers which served to support the centre of the roof, and possibly, at the same time, stood above the roof-level to create a louvre for smoke to escape. The Little Woodbury plan is essentially only a modification of the early houses mentioned above, in which the total enclosed area was divided into a central region and peripheral space. Little Woodbury shows the additional modification of a substantial porch or entrance passage 4.6 m long. Provided with an inner and an outer door, it would have created a trap to prevent cold air from sweeping in. The overall diameter of the house, 14 m, compares with three other large houses of the same general type, one from Cow Down (Longbridge Deverill), Wilts., and one from Pimperne Down, Dorset, both 15 m in diameter, and a third from Old Down Farm, Hants, measuring 11m in diameter. All four houses belong to the period from the eighth to the fifth century: at present no house of comparable size or complexity has been found in the later part of the Iron Age.

A structure of rather different type was found at West Harling, Norfolk. In plan it consisted of a circular ditch broken by two wide causeways, with an internal bank with corresponding openings. Within lay a mass of post-holes which probably belonged to a house-like structure. One interpretation suggests that the roofed area was annular about a central open yard (Clarke 1960, 95), but it would be simpler to reconstruct it as a conventional circular house standing within a ditched enclosure, the ends of the rafters resting on the bank. The possibility that it was a religious building is unlikely in view of the presence of hearths and drainage gullies, which would argue for domestic use. Another West Harling house was of a more conventional structure: a circular setting of posts about 11.5 m in diameter. This too was built in the centre of a circular ditched enclosure about 34 m across.

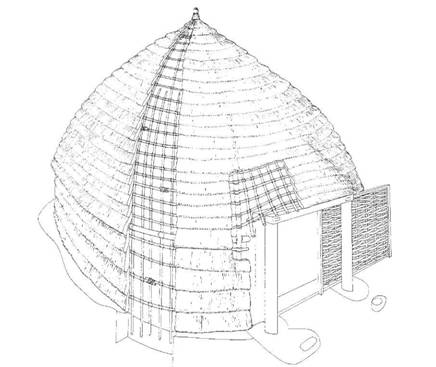

While houses built of individual posts occur widely, and are likely to survive in most archaeological contexts, it is now clear that less substantial forms of house building were not infrequently employed. At Danebury, Hants, for example, the majority of the houses belonging to the Middle Iron Age were constructed of wattle based on vertical stakes some 2 cm in diameter driven into the ground at intervals of 10-15 cm. It was only at the doorway that substantial timbers were employed to strengthen the entrance gap and give support to the door (Figures 12.20 and 12.21). The buildings varied in diameter from 6 to 9 m. How the roof was constructed is a matter of debate: one possibility is that the vertical wall was bound at the top with withies to form a ring beam upon which the lower ends of rafters were based, but it is equally possible that some of the vertical poles were carried up and bound together at the apex to create the framework for a beehive-like structure entirely of wattle which could then have been weather-proofed with thatch. The door frames of the Danebury houses frequently had two vertical timbers on each side of the door with a space of 20-30 cm between. This would have provided a suitable framework to support a movable door of wattle which could have been slotted into place or removed at will. Similar kinds of stake-built structures have been found at the hillforts of Moel y Gaer, Flints., and South Cadbury, Somerset, and at Hengistbury Head, Dorset. Clearly, the survival and recognition of such buildings is dependent on a number of factors and the strong probability remains that while many may have passed unnoticed most will have been destroyed by subsequent agricultural activities. The very simplicity of stake-built houses suggests that the type may once have been widespread.

A second type of less substantial house has been noted at Little Waltham, Essex. Here a number of roundhouses were discovered which were represented archaeologically by foundation trenches 10–14 m in diameter. Two types can be recognized: the first, in which the walls consisted of vertical posts placed in an evenly curving trench, and a second of a more polygonal plan which hints that horizontal wall plates may have been adopted. In both types a ring beam at eaves level would have been all that was required to provide the strength necessary to carry the roof. Ring- groove houses of this type are quite common in southern Britain but the simplicity of the plan may well obscure variation in structure. At Danebury, for example, the walls of one such house were composed of vertical planks placed side by side. Elsewhere vertical timbers appear to have been more widely spaced and were presumably infilled with wattle.

Figure 12.20 Stake-built roundhouse found in the hillfort of Danebury, Hants (photograph: Danebury Trust).

Figure 12.21 Reconstruction of a stake-built house based on excavated evidence from Danebury, Hants (drawing: Christina Unwin).