8

The tribes of the periphery

Durotriges, Dobunni, Iceni and Corieltauvi

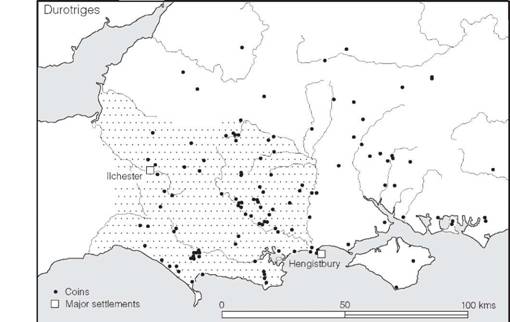

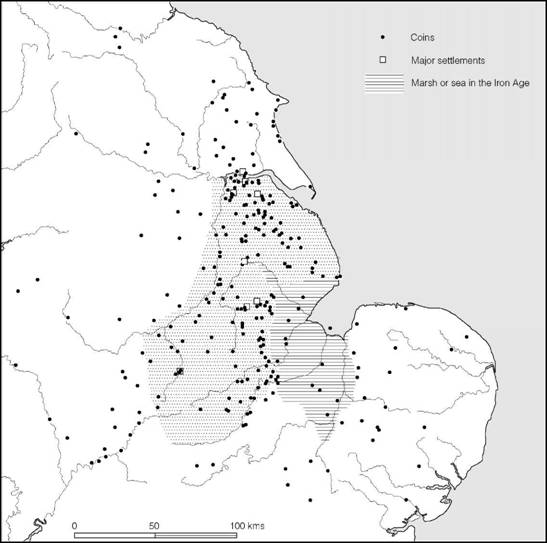

In the Late Iron Age the core zone of south-eastern Britain was fringed by four coin-issuing tribes, the Durotriges, the Dobunni, the Iceni and the Corieltauvi, the numismatic history of each of which was quite distinct from that of its neighbours. The gross distribution of coins of these peripheral tribes (Figure 8.2) is interesting. Not only are tribal boundaries quite closely adhered to but remarkably few peripheral coins are found in the core territory. While this could be thought to imply that there was little intercourse between the core and the periphery it is far more likely to mean that peripheral coinage was unacceptable in the core territories and was melted down for reminting. The reverse is less evident and in the territory of the Dobunni and Corieltauvi, Atrebatic and Trinovantian/Catuvellaunian coins are by no means rare. Such issues no doubt had value in intertribal exchanges. The western fringes of the peripheral tribes are far less easy to define since their boundaries are with non-coin-using neighbours. Even so the distribution maps suggest a fairly rapid fall off.

The Durotriges (Figure 8.3)

The Durotriges were a close-knit confederacy of smaller units centred upon modern Dorset. To the east and north their boundaries with the Atrebates seem to have been marked by the Avon and its tributary the Wylye. The New Forest may have formed something of a buffer zone between the two tribes. Further west Durotrigan coins and pottery extend along the valleys of the Yeo and the Parrett, giving the tribe a narrow outlet to the Bristol Channel. The River Brue would approximate to a northern boundary with the Dobunni and it may be that the marsh- edge settlement of Meare served as a market centre on the interface between the two. The western boundary with the Dumnonii lies roughly on the line from the Parrett estuary to the River Axe. The territory thus defined exhibits a considerable degree of cultural unity, with marked dissimilarities to the cultures of the neighbouring Dumnonii, Dobunni and Atrebates.

The history of the Durotriges can be divided into two broad phases, an early phase, roughly 100–60 BC and a late phase from 60 BC until the Roman Conquest. The early phase was a time of rapid development brought about by overseas trade while the late phase was a time of retraction, isolation and economic impoverishment.

Figure 8.1 The tribes of southern Britain (sources: various).

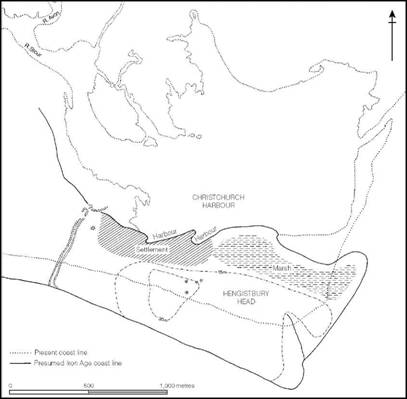

The background to the development of overseas trade c. 100 BC or a little before will be discussed in more detail below (pp. 247–80). Suffice it to say that a major trading axis was established, linking the Solent ports of Hengistbury and Poole Harbour to the north Breton trading stations and, through them, to the Atlantic trading network. The most important of the British ports lay on the northern shore of Hengistbury Head, overlooking the tranquil waters of Christchurch Harbour (Figures 8.5 and 8.6). Here, within the protection of the double dykes which cut off the neck of the promontory, there developed a complex entrepôt with a spacious anchorage, improved by the construction of hards for beaching ships, admirably sited to control the two main river routes into the heart of Wessex. Excavation has shown a concentration of Late Iron Age activity stretching for a kilometre along the shore. Evidence for long-distance trade comes in the form of large quantities of Dressel 1 amphorae, mostly of the 1A type, in which north Italian wine was imported in the first half of the first century BC. Among the other commodities brought in at this time were raw purple and yellow glass and dried figs: no doubt there were many other luxury goods of a kind which leave no trace in the archaeological record.

Figure 8.2 Distribution of the coins of the four peripheral tribes (source: CCI 2003).

The range of commodities amassed for export was considerable. Metals are attested by evidence of smelting and refining. Iron ore was available locally from the headland itself. Copper and tin ore were imported from the West Country and were smelted in the same crucibles to make bronze: a massive block of high-silver copper ore from the borders of Dartmoor was recorded weighing 4 kg. High-silver lead from the Mendips was also imported and was refined by cupellation to produce silver, while gold, in the form of scrap, was stockpiled. In addition to the metalworking activity there is evidence to suggest the manufacture of shale armlets, the extraction of salt and the amassing of quantities of grain brought in from the Wessex hinterland. An unexpectedly high percentage of cows’ teeth (bones are poorly preserved at the site) could hint at the value of hides and salt meat for export.

Figure 8.3 The territory of the Durotriges (sources: author and CCI 2003).

The acquisition of such a range of commodities by those controlling the Hengistbury entrepôt implies well-developed trade networks not only with the hinterland of Wessex but further afield to the metal-rich areas of the south-west. The river Stour provided access both to the Mendips and, via the Parrett, to the Bristol Channel and the metal resources of south Wales, while the south coast route conveniently linked the south-west peninsula with its supplies of copper, tin and cattle to the Solent ports. Hengistbury served various functions: it was not only a place where raw materials could easily be collected together for export but it also supported a range of specialists who could add value to the materials by refining them and manufacturing consumer durables.

The southern orientation of Hengistbury’s overseas links is amply demonstrated by a range of imported Armorican coins and pottery. Most prolific were coins of the Coriosolites, whose territory lay in the Côtes-d’Armor focused on the estuary of the river Rance and the Baie de Saint-Brieuc. Others came from several north-western French tribes: the Osismii, Namnetes, Aulerci Diablintes, Abricatui and Baiocasses. Large quantities of Armorican pottery were also recovered, principally the black cordoned wares made in the territory of the Coriosolites (Figure A:33), but with high percentages of graphite-coated wares and rilled micaceous wares coming from other parts of Brittany. Together this evidence leaves little doubt that the long-distance trade, emanating from the Roman-controlled Mediterranean coast of France, was effected by middlemen providing short-haul links between a network of ports along the Atlantic route. Hengistbury’s immediate trading partner was evidently the Coriosolites whose principal port lay at Saint-Servin close to Saint-Malo in the Rance estuary.

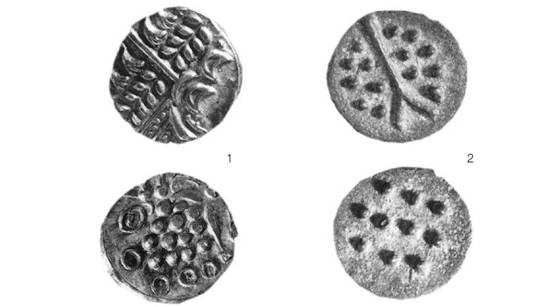

Figure 8.4 Coins of the Durotriges: 1 silver stater; 2 cast bronze unit; twice actual size (photograph: Institute of Archaeology, Oxford).

The archaeological evidence from Hengistbury suggests that after the middle of the first century BC trade along the Atlantic route dwindled dramatically and all but dried up. The immediate reason was probably Caesar’s harsh treatment of the Armorican tribes in 56 BC following their rebellion, but in the long term the virtual monopoly of overseas trade which the tribes of eastern Britain seem to have captured provides a plausible explanation. The Gallic War therefore marks the end of the period of Durotrigan prosperity and heralds nearly a century of economic and cultural isolation. This is well demonstrated by the history of Durotrigan coinage. In the decades immediately before the Caesarian campaigns a gold standard had been adopted, and was maintained during the early stages of the war, for external trade, but already, for local use, a debased coinage of white gold was being produced. Immediately after the war the coinage was further debased: the gold content soon disappeared altogether and then the percentage of silver began to be reduced until about 30 BC, by which time the issues were entirely of bronze (Figure 8.4). Along with this economic collapse came growing cultural isolation.

One effect of the brief period of overseas trade was to introduce into Durotrigan territory an improved ceramic technology involving the potter’s wheel. At first copies of imported north-west French black cordoned wares were made for internal trading purposes but soon a wide range of types was being produced. The local assemblage is distinctive and shows little variation across the region (Figure A:36). The commonly occurring forms include shallow bowls with straight or slightly convex sides, a bead lip and a foot-ring base; high-shouldered bead-rimmed bowls; necked-bowls; large jars with or without countersunk handles; handled tankards; and occasionally tazze. Decoration is usually restricted to simple wavy lines, cross-hatched zones and sometimes the use of dots or rouletting. With very few exceptions, the forms can all be traced back to traditions current in the area in the preceding period, the main difference being that much of the material was now wheel-finished. A few of the vessels, like the tankards, probably developed as copies of metal or wood-and-metal containers, while others, such as the necked bowls and tazze, may well have been inspired by imported north-western French types. The general impression given by Durotrigan ceramics is that production was now largely centralized: fabric analysis has suggested that the main centre lay in the vicinity of Poole Harbour.

Figure 8.5 Hengistbury Head, Dorset (source: Cunliffe 1987).

The decline in the importance of the port of Hengistbury in the middle of the first century BC appears to be matched by a rise in activity in Poole Harbour. Breton pottery and Roman Dressel 1A amphorae found at various points on the south side of the harbour show that already cross-Channel trade was developing in the first half of the first century BC (Cunliffe and de Jersey 1997, 64–5) and a harbour work or jetty of some kind was already in use running between Cleavel Point and Green Island (Markey et al. 2002). In the later first century BC and early first century AD there is ample evidence to show that imported pottery, and no doubt other goods, was reaching settlements in the area on Cleavel Point and Furzey Island (Cox and Hearne 1991) via the Atlantic trading routes, but the volume of that trade appears to have decreased dramatically as new trading networks between Roman Gaul and the Essex coast came into operation.

Figure 8.6 Aerial view of Hengistbury Head, Dorset (photograph: K. Hoskins).

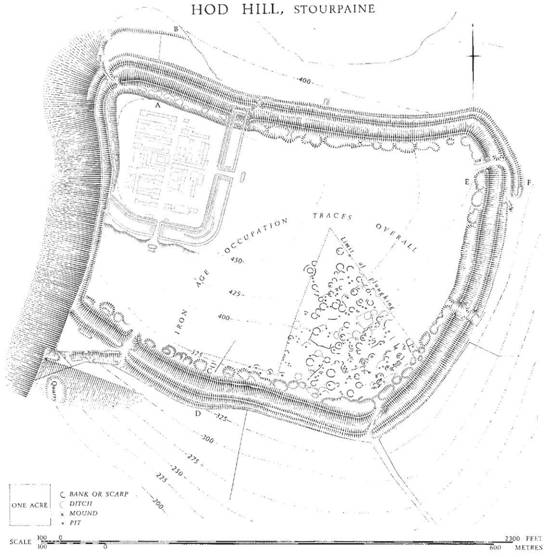

Unlike the Atrebatic and the Aylesford–Swarling regions, where large newly built oppida surrounded by defensive dykes played an increasingly important part in centralizing political power, in the Durotrigan territory trends towards urbanization remained focused on the old hillforts. At Maiden Castle, the 18 ha enclosure was tidied up, streets were metalled and defences were maintained in good order, while the close-packed houses continued to be inhabited and rebuilt. An even more impressive demonstration of a Late Iron Age nucleated settlement is the fort on Hod Hill (Figure 8.7). Within its 21 ha fortified area, the one wedge-shaped quadrant which has escaped modern ploughing is covered with traces of small circular huts, some of them with annexed enclosed yards and many associated with storage pits. Spacing tends to be haphazard but several well-defined street lines can be traced. While it is evident even from the ground survey that not all the huts were in use at the same time, selective excavation has shown that many were occupied during the last decades before the Roman invasion. The excavated sample is not large enough to permit firm conclusions, but it indicates a rapid increase in resident population after c. 50 BC, developing into what can only be described as a town by the time of the invasion.

Figure 8.7 Hod Hill, Dorset (source: reproduced from RCHM Dorset vol. 3).

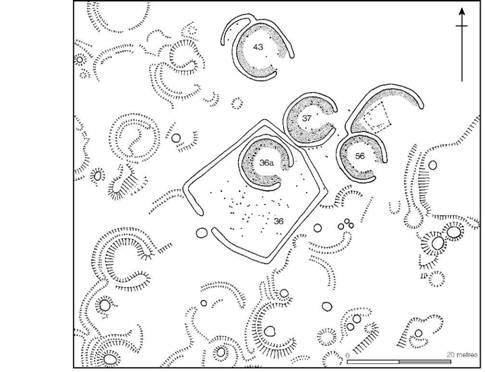

The individual houses were each built within a penannular drainage ditch c. 9–10.5 m in diameter (Figure 8.8). The superstructure consisted simply of a circular setting of upright posts set into the natural chalk and packed around with a low wall of chalk rubble, giving a living area of up to 6 m in diameter unimpeded by central supports. Many of the huts seem to have been provided with a cupboard immediately inside the door on the left-hand side, where weapons could be placed. In two of the huts this space was occupied by a bag of slingstones, and presumably the sling; in another it contained a group of harness-fittings; while in the fourth a spear was placed in the same position. Several of the huts were set within an attached yard, defined by an arc-shaped ditch and low bank. In the case of hut 56 the enclosure housed a rectangular stable suitable for two or three horses, with a space beside it adequate for parking a cart. Hut 36 was unusual in that it lay in the corner of a sub-rectangular palisaded enclosure some 21 m across, the rest of the enclosed area containing timber structures of undefined form. Since it was this hut that appears to have been singled out for bombardment by Roman ballistae at the time of the invasion, the excavator may well be correct in his assumption that it was a chieftain’s residence (Richmond 1968). Its siting, in a prominent position close to the main street which ran towards the principal gate of the fort, is indicative of its importance.

Figure 8.8 Interior settlement at Hod Hill, Dorset, partly excavated (source: Richmond 1968).

Maiden Castle and Hod Hill are not unique among the Dorset forts. Hambledon Hill, for example, appears from a ground survey to have been equally as densely occupied as Hod, and excavations at South Cadbury, Somerset, have demonstrated a similar urban aspect in the immediate pre-Roman period, when the old Middle Iron Age defences were refurbished. The evidence is now sufficiently strong to leave little doubt that many, if not most, of the Durotrigan forts were in active use in AD 43; it was, after all, across this territory that Vespasian had to force his way, destroying one hillfort after another.

Localized defence based on the forts does not necessarily mean that all the forts were permanently occupied on a large scale. It could be argued that the countryside population fled to the protection of the defences only when the threat of Roman attack occurred; indeed, it would be surprising if some such movement did not take place, swelling the population within. Just to the north of Maiden Castle air photography and limited excavation has demonstrated a very considerable apparently unenclosed settlement of Late Iron Age date. It could well be that this was now the centre of nucleated population, leaving the old hillfort only sparsely occupied but conveniently close, to be used and refortified in times of danger.

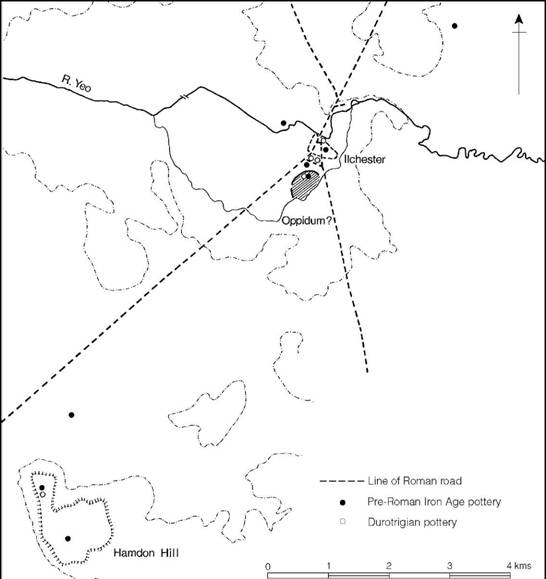

The possibility of a general movement from hillforts to valley locations is further suggested by the recognition of what may be an enclosed oppidum at Wincepool Meadow in the vicinity of Ilchester, 6 km north of the hillfort of Ham Hill (Figure 8.9). Without excavation, however, it is difficult to say more of the potential relationship of the two sites.

The nature of Durotrigan settlement in the countryside is best demonstrated by four sites, all in Cranborne Chase: Tollard Royal, Rotherley, Woodcuts and Gussage All Saints (Figure 12.4). Of these Tollard Royal provides the clearest picture, partly because it has been totally excavated and partly because it was not encumbered by a Roman phase of occupation. The economy of the farm lies well within the tradition of downland and mixed farming stretching back to the second millennium and must represent a typical homestead farm worked by a single family. The adjacent farms of Rotherley and Woodcuts are in much the same tradition, but would appear to represent somewhat larger establishments, perhaps holdings belonging to extended families (Hawkes 1948). The early date of these excavations and the subsequent Roman occupation prevent a more detailed assessment of the Iron Age phase of settlement. However, at Gussage All Saints, the near total excavation of an Iron Age enclosure has provided an impressive example of a farmstead beginning life in the Early Iron Age and continuing in use until the Roman period. There is a marked contrast between the large ditched enclosure of the Early–Middle Iron Age and the cluster of small enclosures, so typical of Late Iron Age farms, which replaced it. The change must imply some shift in the socio-economic systems underlying settlement pattern but these are at present difficult to discern.

The aspects of Durotrigan culture so far considered owe practically nothing to influences derived from the Aylesford–Swarling culture of the south-east. This regionalism is further demonstrated by the continuance of the rite of inhumation, not only until the Roman invasion but for some time afterwards. The famous war cemetery at Maiden Castle provides dramatic evidence for burial ritual in the hours following the Roman attack. The dead, thirty-eight of them, were all interred, somewhat hurriedly to judge by the positions of the bodies, but many of them were provided with a ritual meal contained in a pottery vessel placed beside the body in the grave. Rather less ceremony attended the mass burial at Spettisbury, where more than eighty bodies were thrown into a single pit, but this may conceivably have been a Roman tidying-up operation after a battle rather than an example of native burial practice.

The only three rich burials from the Durotrigan area were also inhumations. One, from Whit- combe near Dorchester, was the burial of a male warrior complete with sword, spear, La Tène II fibula, strap-rings, a spindle whorl and a hammer. The others were both mirror burials. The best known, from Portesham, Dorset, was the burial of a woman, aged between 26 and 45 years, who was buried with a decorated bronze mirror, brooches, a toilet set and part of a Roman strainer. The burial dates to the period immediately after the Roman Conquest. The other, from West Bay near Bridport, was probably also a female burial but all that remained were a few human bones, a pot and the handle of a mirror, exposed in a cliff-fall. All three burials are encompassed within the traditions practised over much of southern Britain and appear to owe little to any particular regional culture or to intrusive elements.

While it is true to say that Durotrigan culture developed in its own characteristic way, little influenced by its eastern neighbours, trading networks were nevertheless maintained. The production of armlets and vessels of Kimmeridge shale became a not inconsiderable cottage industry on the Isle of Purbeck (Calkin 1949). Both finished products and raw shale were exported over some distance, to the Trinovantian/Catuvellaunian area, for example – where it was turned into the elegant pedestal urns and tazze found in several of the rich burials (Denford and Riding 1991). Salt extraction too, which had already begun in the early part of the pre- Roman Iron Age, continued along much of the Dorset coast (Farrar 1963, 1975), no doubt as a specialized commercial enterprise. Yet in spite of this the Durotriges remained an isolated body, with an impoverished coinage, showing little sign of wealth accumulation or the emergence of a dominant élite. When the Romans arrived in AD 43 the natives were unified in their hostility but fought piecemeal and were easily overcome.

Figure 8.9 Late Iron Age settlement in the vicinity of Ilchester, Somerset (source: Leach and Thew 1985).

The Dobunni (Figure 8.10)

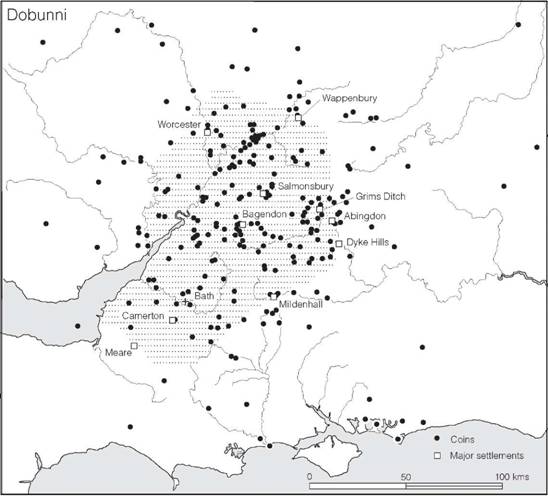

The distribution of Dobunnic coinage places the nucleus of the tribal territory in Gloucestershire, extending into north Somerset down to the river Brue, north and west Wiltshire, Oxfordshire west of the Cherwell, and most of Worcestershire (Hurst 2001). The full extent of this area is defined by the earliest uninscribed gold coinage and continued to be the Dobunnic nucleus until the Roman Conquest (Allen 1961b).

The Dobunni introduced their own coinage in about 35 BC, adopting stylistic motifs from the Atrebates whose issues they had previously been content to use (Figure 8.11). Gold was not plentiful at first but silver was comparatively abundant. Some time about 30–20 BC the first of a series of inscribed staters appeared, bearing names which are assumed to be those of local rulers. Various sequences and chronologies have been put forward. The first, by Derek Allen (Allen 1961b), was accepted by Hawkes who used it as the basis of a complex historical interpretation (C.F.C. Hawkes 1961) now best abandoned. Alternative sequences have since been proposed based on a more detailed study (Van Arsdell 1989; Van Arsdell and de Jersey 1994). The most convincing view is that summarized by de Jersey (1996), which argues that the earliest inscribed issues were those bearing the names of CORIO and BODVOC. The coins of Corio are found throughout Dobunnic territory while those of Bodvoc are concentrated in the northern part, suggesting that he may have been the leader of one polity within the larger tribal area. That one of Bodvoc’s silver issues is inspired by coins of Tasciovanus might imply a political allegiance with the eastern neighbour some time in the late first century. The next issues bear the names COMUX and CATTI. Issues of Comux are rare but the more common issues of Catti occupy much the same territory as those of Bodvoc, implying the continuation of the north–south divide into the early decades of the first century AD. The last issues, of ANTED, probably followed by EISV, are found over the whole of the Dobunnic territory. This seems to indicate that by c. AD 20–30 the whole of the region had come under a single authority.

The implication of there being two discrete polities in Dobunnic territory, separated roughly along the line of the Bristol Avon, is reflected in a similar division that can be traced in the native pottery and its distribution in the first century BC (Figures 5.5, and 5.7). North of the Bristol Avon the principal types included jars and saucepan pot shapes decorated with a zone of either linear tooling or stamping below the rim, types which petrological examination (Peacock 1968) has shown were manufactured in the Malvern area and exported widely, not only to the communities of the Cotswolds but also to the basically aceramic communities further west in the Welsh borderland (Figure 5.5). The form and style of decoration places these stamped and linear-tooled wares firmly within the saucepan pot tradition of the south. Indeed, it is possible to see over this entire area a convergence of development which could only have occurred had the Severn region been in close contact with the south. It is therefore surely no coincidence that it was over precisely this area that gold staters, based on the Triple Tailed Horse types of the Atrebates, rapidly spread following Caesar’s campaigns.

The north Somerset region, on the other hand, was developing a totally different style of ceramics, growing ultimately out of a linear-tooled saucepan pot tradition and influenced partly by technological developments in the Durotrigan area, but involving a new and vigorous art style which derived some inspiration at least from the ceramics of Cornwall (Figure 5.7). This Somerset version of South-Western Decorated Wares is characterized by necked-bowls, saucepan pots and simple bead-rimmed jars, the best of which are decorated with elaborate curvilinear or geometric designs carried out in shallow tooling, frequently incorporating areas of crosshatching. Most of the Somerset South-Western Decorated Wares were made from clays incorporating grit fillers derived from the Old Red Sandstone, Mendip limestone or Jurassic limestone, all of north Somerset origin (Peacock 1969, 43; 1979).

Figure 8.10 The territory of the Dobunni (sources: author and CCI 2003).

To what extent the two ceramic styles represent cultural differences is difficult to say. At the very least, however, they must reflect discrete spheres of social or commercial contact. Taken together with the numismatic evidence mentioned above, it could be argued that both areas retained a degree of identity throughout.

Figure 8.11 Coins of the Dobunni: 1 uninscribed silver unit; 2 Bodvoc, silver unit; twice actual size (photograph: Institute of Archaeology, Oxford).

It is impossible at present to say how long the indigenous traditions of pottery manufacture remained dominant. Wheel-turned south-eastern types occurred to the exclusion of earlier types at Bagendon, Glos., in the first century AD, while at several sites (including Meare, Camerton and Kingsdown Camp in Somerset, and Salmonsbury in Gloucestershire) these south-eastern varieties replace the local types within the decade or two immediately before the conquest. The overall impression given by the present state of our knowledge is that acculturation was slow and patchy, particularly in Somerset, but that ceramics of south-eastern type were being introduced into the east Cotswolds soon after the beginning of the first century AD. Even so, in many areas of the Dobunnic territory native traditions may have continued until the region was eventually subdued in the years following AD 43.

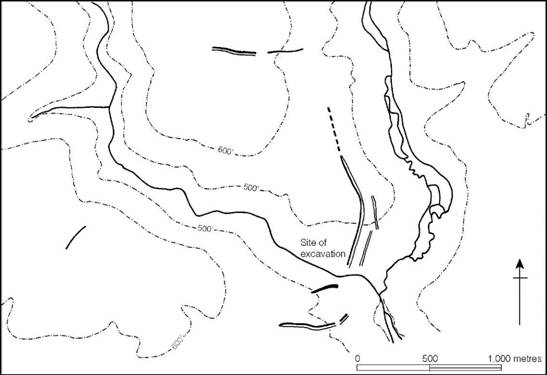

The apparent dual focus reflected in the distribution of pottery and coins strongly suggests the presence of two main ‘urban’ centres. The northern centre was probably at Bagendon, a promontory of about 80 ha partly encircled by linear ditches (Figure 8.12). At one location excavations have defined evidence of occupation commencing at the beginning of the first century AD and continuing until the 60s, by which time the civilian settlement at the Roman town of Cirencester, 5 km to the south-east, was under way. Although the exact nature and extent of the occupation remains to be defined, evidence for metalworking and the minting of coins, together with the relatively large quantity of Gallo-Belgic imported pottery, strongly suggests an important settlement, perhaps a tribal oppidum in south-eastern style.

The location of the southern centre is less certain, but there is some evidence to suggest Camerton, where an impressive array of coins, metalwork and Late Iron Age pottery has come to light over the years. Nor should the possibility of secondary markets within the territory or close to the borders be overlooked. Meare may have served such a function on the southern border with the Durotriges (see below, p. 269), while at Worcester a massive defensive ditch was found beneath the town and Iron Age coins cluster in the vicinity. An enclosed oppidum, here on the river Severn, could have served as a focus for articulating exchange between the Dobunni and the neighbouring Cornovii. Other possible border markets include Wappenbury in the Avon valley, Dyke Hills and Abingdon on the Thames and Forest Hill and Mildenhall on the Kennet. Another centre, well within the territory, is Salmonsbury on the river Windrush. Here a substantial defended enclosure was constructed conforming to the type defined as an enclosed oppidum. It was admirably sited to control movement from the Thames valley, through the Cotswolds, to the Severn valley. Finally there is the massive system of linear earthworks known as the North Oxfordshire Grim’s Ditch, lying on the edge of the Cotswolds between the rivers Glyme and Evenlode. While a Late Iron Age date seems probable the function of the system remains unknown, but its location, close to the supposed boundary between the Dobunni and the Trinovantes/Catuvellauni (at least in their latest stage of political expansion), is suggestive of a border function. It has also been suggested that a major linear earthwork, Aves Ditch, may demarcate the tribal border (Sauer 1999).

Figure 8.12 The siting of Bagendon, Glos. (source: Clifford 1961).

One further site might be considered here – the sacred spring at Bath. The hot water gushing out of the ground close to the valley bottom cannot have failed to have attracted attention. Excavation has shown that the spring was slightly modified in the pre-Roman period so that people could approach the centre to throw offerings, including coins, into the water. The sacred location was given added significance by virtue of its position commanding an excellent crossing point on the river Avon dividing the northern Dobunni from the southern group.

In the remoter areas, hillforts probably continued in use for some time – actively defended, if the evidence for massacres at Bredon Hill, Worcs., and Worlebury, Somerset, is considered to be of this period; but outside the Cotswolds there is little trace of late refortification in the first century AD. This may, however, be due more to the lack of excavation than to lack of continued occupation.

A number of smaller settlements are known but very few have been extensively excavated. Langford Downs, Oxon., however, offers a fairly complete plan of a small farmstead of the first century AD lying on the extreme eastern fringes of the territory. Here two adjacent ditched enclosures both appear to have protected broadly contemporary circular huts, but the full extent of the enclosures could not be traced. Similarities lie with the complex ditched enclosures of the Atrebatic area. Claydon Pike in the Upper Thames valley conforms to the same general type though is more extensive (Figure 12.12). At Butcombe in Somerset, on the north flank of the Mendips, a farm of about this date has been excavated, yielding evidence of circular huts and associated pits of the late pre-Roman Iron Age. These belong to the first phase of a farming settlement which continued in occupation well into the Roman period.

The burial practices of the Dobunni are known from relatively few sites. At Barnwood, Glos., a cemetery containing a single inhumation together with a small cremation group suggests a mixture of traditions not necessarily contemporary. The survival of inhumation is further demonstrated by the Birdlip cemetery, Glos., where at least four inhumations were found in stone-lined graves covered by slabs of limestone and buried beneath cairns of stone 1.2–1.5 m high. The principal burial was of a female who was provided with an impressive array of grave- goods, including two bronze bowls, a silver brooch plated with gold, a bronze mirror, a necklace of amber, jet and stone, an animal-headed knife, a tubular bronze bracelet and four bronze rings.

With so little evidence to go on it would be unwise to speculate too far, but the survival of the inhumation rite, here as among the Durotriges, points to a strong indigenous tradition largely unaffected by the Aylesford–Swarling culture of the south-east. The whole question of the relationship of the Dobunni to the Catuvellauni is a difficult one to untangle. While the intricate political history based on Allen’s interpretations of the coinage (C.F.C. Hawkes 1961) can no longer be sustained in detail, the coin evidence does suggest close relations with the Atrebates at first, but with an increasing Catuvellaunian involvement beginning in the closing decades of the first century BC. The changes in the ceramic technology of the northern Dobunnic area, and the appearance of increasing quantities of Gallo-Belgic imports, again point to direct contact with the east of Britain increasing in the last few decades before the invasion. The evidence could be interpreted as little more than an intensification of trading contacts but the possibility of some form of political domination cannot be ruled out. After all Dio Cassius was of the view that the Dobunni were subservient to the Catuvellauni at the time of the conquest.

The Corieltauvi (Figure 8.13)

The territory of the Corieltauvi, as defined by the distribution of their coinage, lay between the rivers Trent and Nene, with a southern border with the Dobunni somewhere to the south of Leicester. The tribe used to be known as the Coritani but the name has been corrected in the light of new epigraphic evidence (Tomlin 1983).

The coinage of the Corieltauvi shows vigorous and continuous development throughout the period from about 70 BC to the time of the Conquest, with the first dynastic name, VEP, appearing about 10 BC. Thereafter two or three names were commonly inscribed, representing joint rulers or magistrates or else a combination of personal names and mint name (Figure 8.14). The standard of the gold issue was carefully maintained throughout the Gallic War but was eventually reduced to bring it into line with the issues of the southern tribes, and by the end of the war the tribe, like those of the core area, had begun to strike silver to complement the gold, the first issue being based on the style of a contemporary Roman denarius. This would have facilitated trade not only between the tribes of eastern Britain but also with the Continent.

Figure 8.13 The territory of the Corieltauvi (sources: May 1984 and CCI 2003).

The ceramic sequence in the region is comparatively well understood (Figure A:28) from three large assemblages, from Ancaster Gap, Old Sleaford and Dragonby. Three phases can be distinguished. In the earliest the fine ware vessels were hand-made or wheel-finished with highly burnished surfaces. Many were decorated with horizontal zones, usually on the shoulders, infilled with geometric or lightly curvilinear designs executed with a roulette wheel and with shallow tooling enhanced with triple impressed dimples. There is considerable variety and the earliest of the pottery from Dragonby differs in detail from the other two sites but can be regarded as belonging to the same broad tradition. The dating of this early assemblage cannot be defined precisely but it probably began around the middle of the first century BC. The second phase, which develops from the first, is characterized by a greater use of the potter’s wheel and an increasing uniformity in fabric, suggesting the emergence of centralized production. Decoration is now usually restricted to horizontal zoning defined by grooving and cordons occasionally infilled by simple linear shading. Some forms develop beaded rims and pedestal bases. These types are very similar to the Aylesford–Swarling assemblages of the south-east and imply a close contact between the two areas in the post-war period. This need be little more than a parallel development brought about by increased trading connections as the pace of exchange between Britain and the Continent grew. The third ceramic phase reflects a further intensification of this trend. Alongside developed forms of traditional coarse wares, Gallo-Belgic imports, such as butt-beakers, terra rubra and terra nigra, appear together with imported amphorae. The locally produced wares now tended to copy imported forms. This phase probably began in the last decade of the first century BC and continued until the invasion.

A number of large nucleated settlements have been discovered within the tribal territory (May 1976a, 1984). At Dragonby, 11 km south of the Humber estuary, a substantial settlement consisting of ditched enclosures and circular houses and covering some 8 ha, has been partly excavated. Considerable quantities of pottery together with La Tène III metalwork and thirty- three Iron Age coins represent intensive occupation beginning about 100 BC and continuing until after the conquest. A similar long sequence was discovered at Old Sleaford, a site of unknown extent which produced 3,000 fragments of clay moulds probably used for making coin blanks.

Two other sites which have some claim to urban status are Leicester (Ratae) and Lincoln (Lindum), both important Roman towns. At Leicester small quantities of Late Iron Age pottery and metalworking debris have come to light from beneath the Roman settlement, while at Lincoln Late Iron Age occupation has been found just to the south of the Roman town near Brayford Pool. Although the evidence from both sites is sparse the importance which the two locations attained in the Roman period hints at their potential significance in the pre-Roman period.

Among the other Lincolnshire sites which have yielded unusual quantities of Late Iron Age material are Kirmington, Ancaster, Ludford, Old Winteringham, Owmby, South Ferriby, Spilsby and Thistleton (May 1984) but in the absence of extensive excavation their status must remain uncertain. Some may be little more than rich farms, others are perhaps religious centres, but some at least are likely to be major markets possibly with urban functions. Of these, South Ferriby, on the southern shore of the Humber estuary, is admirably sited to command the Humber crossing. The discovery of nearly 200 Iron Age coins and an impressive collection of La Tène III brooches and other metalwork hints at a site of considerable significance.

Two other sites of lesser status have been excavated. At Colsterworth, Lincs., a substantial ditched enclosure containing a number of circular houses was uncovered. The associated pottery shows that the site was occupied during the middle of the first century AD, beginning in the pre- Roman period. Since the number of huts occupied at any one time cannot be accurately assessed, the size of the social group is impossible to define, but in all probability the settlement was a small hamlet or a large farm the status of which was indicated by the massiveness of its enclosing ditch. A rather different kind of settlement was excavated at Tallington, near Stamford. Here a number of roughly rectangular ditched enclosures were laid out along the north bank of the River Welland, in the largest of which was a circular house. The general arrangement is that of a typical farmstead.

Figure 8.14 Coins of the Corieltauvi: 1 uninscribed silver unit; 2 Volisios Dumnocoveros, gold stater; twice actual size (photograph: Institute of Archaeology, Oxford).

A rather more specialized kind of site is represented by the large double-ditched enclosure of Tattershall Thorpe, Lincs., situated on a low terrace overlooking the valleys of the Bain and Witham. The site was in use in the early first century AD but does not appear to have been a habitation. Environmental evidence suggests that it was probably associated with stock grazing. Its location is ideal for access both to summer pasture, on the fen and marsh to the south, and winter grazing on the well-drained sands and gravels of the Bain valley.

No survey of the Corieltauvi would be complete without a brief consideration of the coastline. An extensive survey of the Lincolnshire Fens (Simmons 1980) has shown that in the Iron Age the high-tide line was far inland of its present position (Figure 8.13) but at low tide extensive mud flats would have been exposed, with islands of higher ground in between. While such a shore line would have inhibited communication by sea it provided a valuable range of resources. The marsh edge would have made ideal pasture land for cattle or horses, while along the coastal strip there developed a vigorous salt extraction industry. Sea-birds and the fish would not have been overlooked as a resource. This range of products, together with the fertility of the Lincolnshire soils and the ready supplies of high-quality iron ore, provided the Corieltauvi with a considerable resource potential which could be maximized in order to provide surplus for exchange. The quantities of imported Gallo-Belgic ceramics found on the major settlements and the vigorous, high-quality coinage maintained throughout are indications of their economic stability.

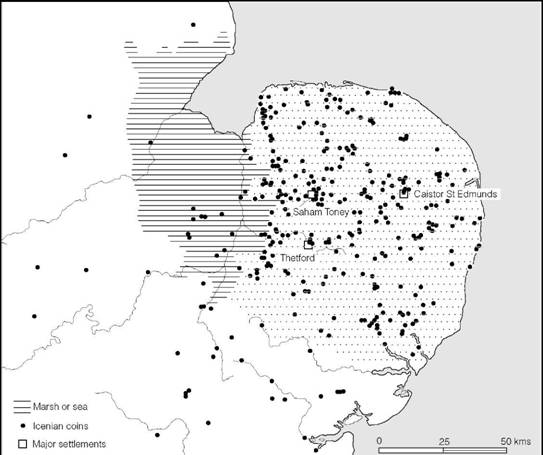

The Iceni (Figure 8.15)

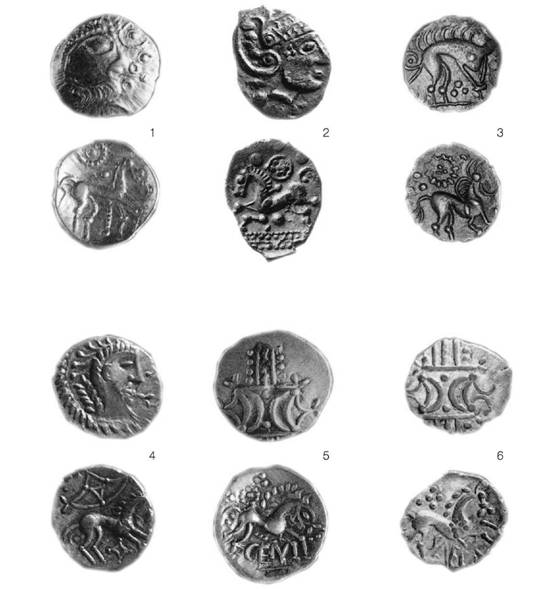

The territory of the Iceni, as defined by the distribution of their coins, centred on Norfolk, stretching westward to the river Nene and southwards probably to the watershed between the Waveney and the Stour. The coinage issued in the area was highly innovative from the beginning (Figure 8.16). The earliest coinage, developing from the Gallo-Belgic C stater, depicted a vigorous wolf, perhaps reflecting a tribal totem, but some time around 40 BC the horse was reintroduced in a variety of localized issues. During this period a number of silver units were minted, some of them bearing highly distinctive heads, and new types with a boar paired with the horse also make their appearance. One of these carried the earliest inscription CAN DVRO. Then followed a major change with the introduction of a pattern of backed crescents on the obverses. A number of inscriptions are found on these types – ANTED, ECEN, ED, EDN, ECE, AESV and SAENV – though what kind of issuing authority these names represent, whether king or mint official, it is impossible to say. The latest coin, issued for Prasutagus, client king of the Iceni after the Roman Conquest, emphasizes the problem with its Latin legend SUB RI PRASTO ESICO FECIT (under the authority of King Prasto, Esico made me).

Until recently there was comparatively little to be said of the archaeology of the Iceni but field surveys, rescue excavations and the impact of metal detectorists have together produced a considerable array of new data (Davies 1996; Davies and Williamson 1999) stressing the distinctive nature of Icenian culture. The two major points to emerge are the apparent increase in population in the Late Iron Age with a colonization of the heavier clay lands, and the appearance of regional groups within the territory.

The most dramatic aspect of Icenian culture lies in the wealth of the ruling élites and the way this was displayed in elaborate metalwork, large quantities of which have now been recovered. Most spectacular are the hoards of gold and electrum torcs and arm rings. The best known are those from Snettisham, Bawsey and North Creake, of which Snettisham provides the largest haul, but to date no fewer than eleven sites have produced precious metal torcs, all but two coming from well-drained soils towards the western border of the tribe (Sealey 1979; Davies 1996, figure 8). The strong probability is that these depositions were made within ritual contexts, but only at Snettisham is it possible to begin to define something of the ritual nature of the larger site where the hoards were found.

The region is also well known for its Late Iron Age decorated bronze horse-gear. Santon Downham, Ringstead and Westhall have all produced large collections of horse-trappings, including bits, terret-rings, harness-mounts, linchpins and other chariot-fittings. But the work of metal detectorists is now bringing to light far more material of this kind, with more than seventy findspots already recorded and the number increasing yearly. There can be little doubt that elaborately bedecked horses pulling chariots were a common sight among the Iceni.

Defended sites are few and not very well dated, but the multivallate fort of Wareham Camp produced a small group of pottery dating to immediately before the Conquest. Other strongly defended sites include Holkham, South Creake, Narborough and Thetford Castle (Davies et al. 1991). Another identifiable settlement type is the rectangular enclosure, a type which seems to concentrate in north-west Norfolk (Davies 1996, 76–7). Little is known of them. One of the more elaborate is the multiple-ditched enclosure at Fison Way near Thetford (Figure 20.18). The site has been fully excavated and shown to have been in use for several centuries. Occupation began in the Middle Iron Age and continued into the early first century AD as a series of small conjoined enclosures. The multiple-ditched rectangular enclosure was built around the time of the Roman Conquest and subsequently enlarged around AD 50–60. Inside was a single large circular structure. Although it is possible that the site was the residence for a member of the élite, a more likely explanation is that it was a temple (see p. 565).

Figure 8.15 The territory of the Iceni (sources: author and CCI 2003).

While no sites that can definitely be regarded as oppida have yet been identified in Icenian territory several areas of extensive Late Iron Age occupation are known, at Caistor St Edmund, Thetford and Saham Toney, all commanding river crossings (Davies 1996, 78–81). Saham Toney has been extensively studied through fieldwork. The main focus at Woodcock Hill has produced a considerable collection of metalwork including four gold coins and sixty silver issues of the Iceni. The site lies at the junction of the Breckland and the boulder clay plateau of central East Anglia where a major north–south route crosses a tributary of the river Wissey. It is a location well suited for the development of an urban settlement, but without excavation the status of the site must remain in doubt.

The relationship of the Iceni to their southern neighbours, the Trinovantes/Catuvellauni, is largely unknown, though coins from both were exchanged in each other’s region and wheel-turned pottery of Aylesford–Swarling type was accepted and adopted by the Iceni. That said, the archaeological evidence would suggest that the Iceni retained their distinctive identity throughout, and in the early years following the invasion remained self-governed by their king Prasutagus who ruled as a client king under the authority of Rome. This was the tribe which, less than twenty years after the invasion, was to produce the energetic and almost successful war leader Queen Boudica.

Figure 8.16 Coins of the Iceni: 1 early horse/face silver unit; 2 Bury C silver unit; 3 boar/horse silver unit; 4 face/horse silver unit; 5 ECEN silver unit; 6 IAENV silver unit; twice actual size (photograph: Institute of Archaeology, Oxford).

Summary

The four coin-issuing tribes of the peripheral zone separated the southern core zone from the less developed areas of western and northern Britain and it was through their territories that raw materials and other commodities had to pass in the period of intensified trade that characterized the Late Iron Age. Thus they formed a buffer zone between the developed and underdeveloped parts of the island. Their socio-economic systems must, therefore, have evolved to provide the enabling mechanisms necessary for the through flow of products. The emergence of a peripheral zone, along the Jurassic Ridge, is no accident since this broad geomorphological region, providing ease of communication along its length, effectively divides Britain into two parts, each with different resource potential, microclimate and degree of access to Continental trading networks. The communities occupying the ridge would thus become subjected to economic forces once cross-Channel trade intensified. This may have led to the emergence of large tribal entities by the coalescence of smaller ethnic groups and would, in any event, have necessitated the development of a coinage to facilitate exchange.

The different ‘histories’ of the four tribes reflect changes in the orientation and intensity of trade. The earliest trading axis favoured the Solent harbours and thereby the Durotriges, but by the time the Gallic War was over a new eastern axis had been created, leaving the Durotriges to become isolated and impoverished. The resources of west Britain could now be reached via the Upper Thames valley and across the northern part of Dobunnic territory, while those of the north called for a route across the Chilterns and through Bedfordshire, skirting the fen margin, to the southern part of the Corieltauvian territory. These two routes were in all probability broad corridors along which exchange goods passed in both directions, making use of a complex system of social relationships. One might anticipate that such enhanced activity created conditions for exceptional change. Some evidence for this can be found in the archaeological record. In the Middle Thames region, for example, a bewildering variety of coins are found, making it difficult to decide in which tribal territory the region lay: such a mixture could have come about as the result of constant traffic between the eastern communities and the northern Dobunni. The northern ‘corridor’ through the Chilterns and across Bedfordshire is probably reflected in the dense scatter of élite burials belonging to those able to benefit from controlling the passage of goods. While it must be admitted that this picture is both incomplete and oversimplified it has some value in helping to focus on the complex processes at work at the time.