20

Beliefs and behaviour

The evidence available for studying the belief systems of Iron Age communities is varied both in quantity and quality and in its geographical spread across the country. Among the various categories, the most prolific is direct evidence for the disposal of the dead which comes not only in the form of regular burials but in the less tangible traces of excarnation. Other displays of belief are reflected in a varied array of deliberate depositions thrown into rivers, lakes or bogs or placed in the ground in specially dug holes or in existing pits or ditches. To this may be added a few disparate literary references concerned largely with the Druids and the less tangible assumptions which can be drawn from the limited place-name evidence. Together this array of sources offers the impression of a highly complex belief system pervading the everyday life of the people and even present in their perception of landscape.

Burial rituals

It has frequently been said that little trace survives of the burials of the Iron Age period in Britain, and by comparison with the large cemeteries of Continental Europe, this might at first sight appear to be so, but when the material evidence is amassed, a well-defined series of ritual practices can be distinguished which can be seen to change over time and to show variation reflecting both long-established regional traditions and the external influences (Whimster 1977, 1981). Standing back from the array of available evidence we may define three broad chronological stages: the eighth to sixth centuries when, for the most part, the Late Bronze Age preference for cremation was coming to an end; the fifth to first centuries when a complex of practices involving inhumation and excarnation are to be found across the country; and the first century BC-first century AD when cremation burial was reintroduced into the south-east. It will be convenient to present the discussion of burial practice in these three chronological stages.

The eighth to sixth centuries BC: the end of the cremation tradition

In the first part of the first millennium BC the principal recognizable method of disposing of the dead was cremation, the ashes being buried, either urned or un-urned, in cemeteries which sometimes originated at the sites of older barrows. Occasionally ashes were buried under individual barrows, usually much smaller than those of the second millennium. These practices continued throughout the seventh, sixth and probably fifth centuries. Many urnfields show signs of continued use and, in all probability, most of the old-established burial grounds were maintained well into the sixth century. Since, however, many of the later cremations were buried without grave-goods or pottery containers, there is nothing with which they can be dated unless by a series of radiocarbon assessments.

The disposal of the dead in urns placed under small individual barrows is well attested in the seventh to fifth centuries. Sometimes cemeteries of barrows are found, like the small group of round barrows on Ampleforth Moor, Yorkshire (Figure 20.1), which have produced pottery characteristic of the seventh century together with two confirmatory radiocarbon dates. The barrows were simple, ranging from 7.3 to 9.7 m in diameter and less than 1.5 m high; each was surrounded by a shallow ditch. Burial was by means of cremation: each was placed in a small pit or scattered on the original ground-surface. Other apparently isolated barrow burials are known across southern Britain. Beneath slight mounds at the Caburn, Sussex, Buntley and Creeting St Mary, Suffolk, and Warborough Hill, Norfolk, ashes have been found in pottery urns of the Kimmeridge-Caburn type, indicating a date in the eighth to sixth centuries. Burials of this kind are direct descendants from preceding Bronze Age traditions.

Inhumations of this early period are much rarer. One possible example has been found under a barrow at Beaulieu Heath in the New Forest, Hants. The barrow, barely 4.6 m in diameter and surrounded by an irregularly cut ditch, was built of turf and survived to a maximum height of 0.6 m. On the original ground-surface beneath the mound lay the remains of several wooden planks, a bronze ring, smaller fragments of bronze, two small pieces of iron and a sherd of a coarse-shouldered jar of Early Iron Age type. While no interpretation can be offered with assurance, it is possible that the remains represent a cart burial of Hallstatt type, the bones of the inhumation having been totally destroyed by the acidity of the soil.

A second, though ill-recorded, inhumation burial was discovered at Ebberston in Yorkshire in 1861 and briefly reported to a meeting of the British Archaeological Association held in that year. The account describes a bronze sword (of Hallstatt C type) and its chape, found ‘together with another sword and a quantity of human bones’. Both swords were broken into four pieces. It is impossible to be sure now of the nature of the find, but the apparent ritual breaking of the weapons is a feature which can be paralleled among Continental burials and might be thought to support the suggestion that the Ebberston deposit was a genuine inhumation in Hallstatt C style. If so, it is the only example yet known in Britain.

A surprising difference exists between Britain and the Continent in the eighth and seventh centuries. On the Continent most of the Hallstatt swords known come from burials, whereas in Britain all except for Ebberston come from rivers. One possible explanation of this phenomenon is that in Britain the dead were cremated and disposed of, with their equipment, in rivers. This would account both for the riverine distribution of swords and chapes and the relative lack of burial grounds. Such an hypothesis is impossible to prove but the ritual is well attested among more recent societies and need occasion no surprise.

The fifth to first centuries: inhumation traditions

By the fifth century BC the cremation tradition had been largely replaced by inhumation, but practices varied considerably across the country. Two distinct regional rites can be recognized, in Yorkshire and in the south-western peninsula. But elsewhere the evidence is more diverse and more scattered. Here, although some regular cemeteries are known, bodies and body parts are frequently found in ‘domestic’ contexts suggesting a more complex rite de passage involving excarnation. In the first century BC and early first century AD, after the rite of cremation had begun to be widely adopted in the south-east, inhumation and occasionally cremation burials, accompanied by swords and shields or by mirrors, are found sparsely distributed over most of the south and east of the country. It will be convenient to describe these various traditions separately.

Figure 20.1 Yorkshire cemeteries (sources: Skipworth Common, Stead 1961; Ampleforth Moor, Wain- wright and Longworth 1969).

Figure 20.2 The Arras burials in Yorkshire (source: Ramm 1978 with additions).

In Yorkshire, a new and quite distinctive burial practice appeared in the late fifth century and forms part of what is referred to as the Arras culture (pp. 84–6). Close similarities with burial traditions in northern France are strongly suggestive of a cultural link between the two regions. Until comparatively recently the Arras culture was represented almost entirely by its burials (Stead 1979, 1991; Dent 1982, 1985). Three separate ritual practices are represented: the grouping together of small barrows in large cemeteries; the occasional rite of vehicle burial; and the practice of surrounding individual barrows with a rectangular ditched enclosure. Many barrow cemeteries are known (Figure 20.2), ranging from small clusters to larger groups such as Eastburn (75), Scorborough Park (170), Dane’s Graves (up to 500), and Burton Fleming (500+). The individual barrows were usually small, up to 9 m across, and normally covered crouched inhumations, although very occasionally extended inhumations and even cremations have been found. In many cases the barrows were surrounded by circular ditches but cemeteries of rectangular ditched barrows are becoming increasingly common as aerial surveys proliferate (Ramm 1978; Stead 1979, 29–35; Mytham 1995).

Generally the burials were without elaborate grave-goods but some were provided with brooches and joints of pork. Richer graves occur sporadically, and more rarely mortuary vehicles were buried with the dead. The vehicle burial at Dane’s Graves (Figure 20.3) lay beneath a barrow some 8.2 m in diameter in a rectangular grave-pit about 0.8 m deep and measuring 2.6 by 2.3 m. The deposits consisted of two crouched inhumations laid on the bottom of the pit together with the remains of a dismantled cart and several items of harness-fittings. The ‘king’s barrow’ at Arras was a little larger, covering a circular grave-pit some 3–3.5 m in diameter, in which had been placed a single extended inhumation with the bodies of two horses, one laid on either side. The wheels from the vehicle had been removed and propped against each of the horses while the harness-trappings, including two harness-loops, five terret-rings and two horse- bits, were placed together with the two linchpins in the western half of the grave. Close to the head of the burial had been placed two pigs’ heads, presumably as an offering to the spirit of the deceased.

Figure 20.3 Vehicle burials from the Arras culture (sources: Dane’s Graves and Pexton Moor, Stead 1965; Wetwang Slack, Dent 1985).

Figure 20.4 Burial from Wetwang Slack, Humberside (photograph: Bill Marsden).

Another example of a vehicle burial, one of the few to be excavated under modern conditions, was found at Garton Slack, near Driffield, in 1971. Here the inhumed body had been placed on the bottom of the grave-pit and covered with the funerary cart. The two twelve-spoked wheels had been removed and laid on either side of the body. The grave-goods included the harness- trappings, consisting of two bits, five terret-rings and four buckles, a whip and a pig’s head as an offering.

In 1984 three remarkable vehicle burials were discovered in close proximity to each other at Wetwang Slack (Figures 20.3 and 20.4). All three were buried in pits set beneath rectangular ditched barrows. In each case the body was flexed and was placed together with grave-goods in a box structure, presumably the body of the vehicle, above the two wheels of the cart which had been dismantled and laid side by side on the ground beneath. Burial 1, that of a young male, was accompanied by chariot- and harness-fittings, a long sword, seven spears, iron coverings for the spine of a wooden shield and the forequarters of a pig. In Burial 2, in addition to the vehicle and harness parts, there were personal possessions, including a mirror, a decorated bronze box of cylindrical form with a chain for suspension, and a gold and iron pin decorated with coral. Two forequarters of pig were placed over the stomach of the dead person. The third burial, like the first, was accompanied by weaponry - a large iron sword, together with its suspension rings and iron fittings for the shield. With such a comparatively small sample available for study generalizations are difficult, but it is tempting to contrast the warrior equipment of Burials 1 and 3 with the essentially female equipment of Burial 2. This might suggest that the vehicle rite was associated with status rather than gender.

Another vehicle burial was discovered in the same area, at Garton Station, in 1985. Here the ritual differed from the others mentioned in that the wheels were placed together upright against the side of the grave-pit. Some 400 m from Garton Station, at Kirkburn, another vehicle burial was identified and excavated in 1987. The wheels had been dismantled and laid on the base of the grave, with the body placed at the junction of the two wheels with legs flexed. A coat of iron mail armour had been placed over the body with two groups of pig bones. The wooden yoke had been laid along the west side of the corpse. It was covered by a rectangular barrow surrounded by a ditch.

In 2001, yet another vehicle burial was found at Wetwang village during the course of building work. The vehicle had been taken apart, with the yoke laid at the north end of the grave and the axle at the south end. Between were the wheels placed flat on the bottom of the grave- pit, with the box of the vehicle, containing the body, next to it. The corpse, a mature female, was arranged in a crouched position accompanied by an iron mirror and joints of pork.

As will be apparent from the above discussion, most of the vehicles found in the Arras graves had been dismantled at the time of burial, but at Pexton Moor the cart was buried intact, with its wheels set into two oval pits dug into the bedrock (Figure 20.3). The barrow in this example was also surrounded with a rectangular ditched enclosure.

The principal elements of the Yorkshire cart burials can therefore be seen to be inhumation - either extended or contracted - the burial of the mortuary cart itself, the deposition of some or all of the harness-fittings, the occasional ritual sacrifice and burial of the horses, and the provision of some personal ornaments and food offerings, usually pork. These features can all be paralleled among contemporary Continental burials, but the rarity of pottery and weapons in the Yorkshire group serves to distinguish the area. It should, however, be stressed that the Wetwang Slack and Garton Slack cart burials were simply the élite element buried in a much larger cemetery running for more than a kilometre along the valley bottom (Figure 20.5), the ‘normal’ burial rite being simple inhumation in a small pit surrounded by a rectangular ditch. Grave-goods, if they occurred, were restricted to small items of personal equipment such as brooches. The burial evidence from the Yorkshire cemeteries is rich in detail reflecting on ritual and difference in status. At several sites including Garton Station and Rudston there is clear evidence that corpses had been speared in the grave using a particular type of insubstantial spear. Why this was deemed necessary is a matter of speculation. Elsewhere, while the ‘richer’ burials were provided with joints of pork, others, of lesser status, were buried with mutton (Stead 1991). Clearly there is much to be learned from differences of this kind but often the link between observation and explanation is difficult to make with assurance.

Apart from the Arras group in Yorkshire, evidence for cart burial elsewhere in Britain is rare, though not entirely absent. At Mildenhall, Suffolk, an extended inhumation was found, possibly under a barrow, accompanied by a long iron sword, an axe and a gold torc and flanked by the skeletons of two horses. No fittings of a cart appear to have been found, but the discovery was made some years ago and is ill-recorded; the likelihood that significant details passed unnoticed is extremely high. An even more interesting burial was found at Newnham Croft, Cambs., where a contracted inhumation was recovered accompanied by three brooches, one of which was penannular, a bracelet, part of what may be the head-harness for a pony and four simple bronze rings. Dating cannot be precise but on stylistic grounds the decorated bracelet is thought to belong to the fourth or third century. Again, there is no positive evidence for a cart. A third example comes from Fordington, just outside Dorchester in Dorset, where the bones of a man and a horse were found in 1840 together with a bronze bit of Iron Age type. Finally at Newbridge, just west of Edinburgh airport, a vehicle burial of the fifth to fourth centuries BC was discovered. The vehicle was intact when buried, with the lower parts of its wheels set in pits in the base of the grave. The fact that only four possible cart burials have been found outside Yorkshire is a fair indication that the rite was not widely adopted in Britain but the recognition of square barrows at Kirkby la Thorpe, Lincs., and Diddington, Cambs., suggests that some elements of the Arras burial rite might have been adopted more widely in eastern England.

Figure 20.5 The cemetery and settlement at Wetwang and Garton Slack, Humberside (source: Dent 1982).

Figure 20.6 Inhumation cemeteries in south-western Britain (source: author).

In south-western Britain a distinctive regional burial practice can be distinguished involving inhumations buried in individual graves. Five cemeteries have so far been identified (Figure 20.6): Mount Batten in Devon, and Harlyn Bay, Trelan Bahow, Trevone and Trehellan Farm in Cornwall. The older finds were poorly recorded, but useful details are provided by the cist excavated at Trevone in 1955, the re-examination of part of the Harlyn cemetery (Whimster 1978) and the thorough excavation of a small cemetery of some twenty-one burials at Trehellan Farm, Newquay, in 1987. The bodies were usually, though not invariably, buried in crouched positions, the graves were often lined with stone slabs (though not at Trehellan Farm) and were roughly arranged in rows, and there was a distinct preference for siting cemeteries within sight of the sea. Grave-goods frequently accompanied the dead, but were usually restricted to personal equipment such as pins, bracelets and fibulae, though occasionally more expensive items such as mirrors, necklaces and bronze vessels were included. One burial found at Bryher on the Isles of Scilly contained a mirror as well as a shield and a sword but this may reflect a different and more widely spread tradition (below, p. 557). The surviving material from these south-western burials suggests a date range spanning the Middle and Late Iron Age from the fourth century BC to the mid-first century AD.

Cist burials are recorded sporadically from other parts of Britain. In Wales, for example, the famous bronze ‘hanging bowl’ (now thought to be the lid of a vessel) from Cerrig y Drudion, Clwyd, was found in a cist which may have been constructed originally for burial, while in Scotland many of the burials which can, on the basis of their grave-goods, be assigned to the Iron Age have been found in cists, either isolated or arranged in cemeteries as at Cairnconan, Angus. Inhumations of this kind continued in use into the second and third centuries AD.

Over much of south-eastern Britain evidence of careful burial in cemeteries is by no means common, though human remains are frequently found on settlement sites in a variety of contexts. Before considering what this may mean in terms of belief systems and ritual a brief review of the highly varied evidence must be offered.

Three regular cemeteries have recently been identified, at Yarnton, Oxon., Kemble, Glos., and Suddern Farm, Hants (Figure 20.7). All were of Middle Iron Age date and contained a number of crouched inhumations in shallow graves. The burials were usually unaccompanied, apart from one individual at Suddern Farm who was buried with an iron brooch. The Kemble cemetery was small, comprising only five burials; Yarnton produced thirty-five or so interments in two main clusters, while Suddern Farm was significantly larger but only a small sample has been excavated.

It is quite possible that cemeteries of this kind were fairly widespread and may be found at the fringes of many of the settlements in the region. The fact that so few have yet been identified may simply reflect the emphasis that has been placed on the excavation of the actual settlement nuclei rather than the peripheral zones around them.

The habitation sites themselves normally produce human remains deposited in pits, ditches or occupation accumulations within the settlement. The human remains include complete burials, burials of partial but articulated bodies, and isolated human bones. Such deposits are a common feature found throughout the south-east of Britain. A few examples will suffice to give an idea of the range. On a number of settlement sites, both open farms and hillforts, complete articulated bodies have often been found tucked away in disused storage pits (Figure 20.8). In most examples the body lies flexed, often quite tightly, on the pit bottom close against one side of the pit, and in a number of the better-excavated examples heavy stones have been recorded over the body. Occasionally these pit burials have been found to pre-date rampart extensions, as at Hod Hill and Maiden Castle in Dorset, in situations suggestive of foundation burial, but more normally pit burials are found scattered at random throughout the settlement areas. This rite was widespread throughout central southern Britain and appears to be represented in all areas where storage pits were dug.

A number of settlement sites in the south-east have produced evidence of what might superficially appear to be more casual treatment of dead bodies. Isolated human bones are frequently found in rubbish deposits and in some cases articulated parts of human carcasses have been found in pits along with other occupation debris. At Wandlebury, Cambs., for example, a child’s body less the legs was apparently wrapped in a cloth or sack and thrown into a pit, while at Danebury limbs and pieces of human trunk occur sporadically. In one case at Danebury, a deliberate deposit was created in a specially dug elongated pit in which had been placed three legs, part of a trunk and a lower jaw. Unlike the other pits, this one had been left open for some time, the fragments of body remaining exposed to view. It is difficult to resist the conclusion that the deposit had ritual overtones.

Another factor of some significance is the apparent interest shown in the human head (Figure 20.9) (a matter which will be returned to below). On several occupation sites skull fragments are noticeably more common than other human bones. Thirty-two fragments of human skulls were found at All Cannings Cross, Wilts., four of which had been deliberately shaped, one perforated for suspension, the others polished by use. Similarly, at Lidbury, Wilts., a piece of cranium had been carefully shaped and perforated. It must be assumed that skulls were selected for special treatment, which eventually resulted in token pieces being retained by individuals, perhaps as good-luck charms.

Figure 20.7 Part of the Middle Iron Age cemetery at Suddern Farm, Hants (photograph: Danebury Trust).

Figure 20.8 Pit burial from Danebury, Hants (photograph: Danebury Trust).

Clearly what we are observing in the evidence of the disposal of human remains in central southern Britain is a pale reflection of highly complex belief systems and the rites associated with them (Cunliffe 1995, 72–9; 2000, 128–34). The most likely explanation of the disparate data presently known is that the rite de passage surrounding death involved a period when the body of the deceased was exposed, perhaps on a platform in a specially defined area. Excarnation of this kind has been widely practised in the past and still features in parts of the world today. In such a system exposure may be conceived of as a temporary stage – a liminal period while the spirit was still hovering – after which formal burial may have taken place. If the bodies had been bound and wrapped on death the still-wrapped remains might then have been taken down at the end of the liminal period and interred in graves dug in designated cemeteries. Alternatively they could have been carried into the settlement for special burial, perhaps as part of propitiatory rites. Some such explanation would also accommodate the partial bodies and isolated bones found within the settlement area.

A normative mode, involving excarnation followed by burial or reincorporation, could explain the existing evidence, but that alternative scenarios may account for some deposits should not be overlooked. Some of the bodies in pits could have been deliberate sacrifices, while skulls might have been trophies of enemies (below, p. 570). Similarly, partial bodies could represent localized episodes of violence or desecration, or even insult cannibalism. All these activities are reflected in the literary accounts of Iron Age society in Europe. To distinguish precisely the context of deposition is seldom possible, and depositions, apparently similar, may be the end products of quite different acts.

Figure 20.9 Skull burial from Danebury, Hants (photograph: Danebury Trust).

While the great majority of burials from south-eastern Britain conform to this broad type there are a few isolated exceptions. At Bromfield, Salop, an extended inhumation accompanied by a brooch of La Tène I type, a ring and a pendant was found surrounded by a circular ditch, while at Great Houghton, Northants, a shallow circular pit contained a crouched inhumation buried wearing a lead torc around the neck. These examples reflect differences in regional behaviour which may well prove to be widespread.

Finally it is necessary to consider what appears to be a distinctive burial rite adopted throughout the south-east of Britain from the late second century BC until the Roman invasion. The rite involves burial of an élite individual accompanied by weapons appropriate to a warrior or by mirrors and sometimes bowls more appropriate to female burials.

The warrior burials form a distinctive group, characterized by the rite of male inhumation accompanied by weapons, the bodies being placed in single graves without barrows (Collis 1973) (Figures 20.10 and 20.11). The largest concentration of warrior burials is to be found in Yorkshire at North Grimston, Bugthorpe, Grimthorpe, Kirkburn, Rudston, Garton Station, etc. It is a tradition which clearly grows out of the élite burial practices of the fourth and third centuries BC. While many of the warrior burials in this region were comparatively modest, a few like North Grimston, Bugthorpe and Kirkburn, by virtue of the high craft skill lavished on the swords and sheaths, must have been warriors of high status.

Figure 20.10 Warrior burials from Owslebury, Hants, and Whitcombe, Dorset (source: Collis 1973) and Mill Hill, Deal, Kent (source: Parfitt 1995).

Elsewhere in the country warrior burials are far less common, but examples have been found at Shouldham, Norfolk, Owslebury, Hants, St Lawrence, Isle of Wight, Mill Hill, Deal, Kent, Whitcombe, Dorset, and Bryher, Isles of Scilly. The warrior at Owslebury was provided with a long iron sword in a wooden sheath, together with the rings and scabbard hook for attaching it. By his side was a spear, broken so as to fit into the grave. The body was covered by a wooden or leather shield of which the central bronze boss now survives. The burial at Mill Hill, Deal, was rather more elaborate. He too had a sword and shield, but the sword was in a sheath decorated with bronze while the shield was bronze bound and with a decorated boss. The dead man wore a bronze crown with engraved curvilinear decoration and was also accompanied by an elaborate brooch, a strap-link and a suspension-ring all decorated with coral knobs. The burial, which probably dates to the second century BC, is the first to be made in a cemetery which continues to develop into the Roman period. The inhumation found in a cist at Bryher offers another variation in that not only was the deceased accompanied by a sword and shield but a decorated mirror was included as well. It is not clear how this should be interpreted but there is nothing inconsistent in allowing that a male possessed a mirror or that a female could be of warrior status.

Parallel with the warrior burials there appear a number of rich female burials, usually characterized by the presence of mirrors, beads, bronze bowls and other trinkets appropriate to female attire (Figure 20.11). One of the best recorded of the group was discovered at Birdlip in Gloucestershire in 1879. Three cist graves were found, the centre one containing the burial of a rich female, with a male on either side. Her body was extended and over her face a large bronze bowl had been placed; a smaller bowl lay near-by. The other grave-goods included a gilded silver fibula, four bronze dress-rings, a bronze armlet, a superb knife with a bronze animal-head terminal, a necklace of amber, jet and marble, and an engraved bronze mirror. The burial at Portesham, Dorset, in addition to the mirror, included a toilet set, brooches, a Roman bronze strainer and an iron knife. The rich female burials at Trelan Bahow, Cornwall, and Mount Batten, Devon, were also interred in cists, placed in larger cemeteries.

In the south-east of Britain, where the rite of cremation became popular in the first century BC and first century AD, a group of mirror burials have been identified, with the deceased cremated and the ashes placed in an urn. At Colchester, Essex, the cremation was contained in a pedestal urn accompanied by a range of accessory vessels. The metalwork, including an engraved mirror, a bronze bowl and a bronze pin, serves to link the grave to the general category of rich female burials. Another was found at Dorton, Bucks. Here the body was cremated and accompanied by a mirror contained in a wooden box, together with three amphorae, two flagons and a cup; while at Chilham Castle, Kent, in addition to the mirror the cremation was furnished with a pair of La Tène III brooches dating to between 70 and 50 BC.

The tradition of including mirrors with the departed can be traced back to the fourth century at Arras in Yorkshire, where two graves contained mirrors. The graves at Mount Batten, Birdlip, Colchester and Portesham date to the first century AD. Like the warrior burials, there is no need to attach any cultural significance to the type; they merely represent the standard practices involved in burying moderately wealthy women.

There is a third type of inhumation which might be considered sufficiently distinctive to be regarded as involving a separate ritual practice. At Burnmouth in Berwickshire and Mill Hill, Deal in Kent, extended inhumations have been found, each provided with a pair of bronze spoons. In each pair one spoon was marked with a cross, the other had a small hole punched to one side. Spoons of this kind have been found in various parts of Britain. Some occur in contexts which might suggest ritual deposits. At Crosby Ravensworth in Westmorland a pair was discovered by a spring in a bog; at Penbryn in Cardiganshire another pair had been buried under a pile of stones; the river Thames produced a single spoon and some of those from Ireland were probably from bogs. It is difficult to resist the conclusion that these spoons were in some way connected with ritual procedures. If so, it may be that those with whom they were buried were involved in the practice of religion. This is, of course, pure speculation but it is not too much to expect that the graves of the religious leaders of the community may have been distinguished in some way, as were those of the aristocratic class.

Figure 20.11 Distribution of burials with swords and mirrors (source: author).

Over much of the British Isles inhumation remained the basic rite up to the time of the Roman Conquest. In the territory of the Durotriges, for example, a group of victims of the Roman advance were hastily buried in a cemetery at Maiden Castle. Even though the military situation was tense, trouble was taken to inhume the bodies in specially dug graves and to provide them with ritual meals buried alongside in pottery containers. Inhumation rites were very deeply rooted in Durotrigan territory, and even after the Roman Conquest, when cremation became the norm, the bulk of the population continued to be buried in the old inhumation manner (Whimster 1981).

The first-century BC to first-century AD cremation tradition of the south-east

In the south-east, cremation became increasingly common from the beginning of the first century BC. The normal practice was to bury the ashes of the deceased in an urn in a well- defined cemetery area. A wealth differential is clearly reflected in the nature of the ancillary equipment buried with the ashes. The simpler graves were without grave-goods but a number were provided with small articles such as brooches and other personal trinkets. The richer individuals were buried either in or with bronze-plated buckets, and occasionally, as in the case of the rich graves at Aylesford and Swarling in Kent, other bronze vessels were included (pp. 153–4). In Essex and Hertfordshire, a group of extremely rich burials have been defined, characterized by a deep grave-pit containing considerable volumes of wine stored in amphorae together with the vessels and other equipment appropriate to its consumption. The ritual belief behind such aristocratic burials was evidently to provide the dead man (or woman in the case of Dorton) with the means of feasting and amusement in the afterlife to which he or she had been accustomed on earth. Burials of this kind were being undertaken in eastern England from the early first century BC until the Roman Conquest (p. 155).

The most informative of the cremation cemeteries to be excavated in recent years is the site at Westhampnett, West Sussex, where virtually the entire ritual complex has been uncovered (Figure 20.12). The cemetery comprising 161 cremations represented burial over a forty-year period in the first half of the first century BC. All the burials were arranged around the southeastern circumference of a circular space which was kept open and clear throughout. Just beyond the graves, and concentrating to the west and east of the circle, were a number of X-, Y- and T-shaped features mostly representing the sites of the funeral pyres, while beyond these to the east were four rectangular structures identified as shrines. A single cremation with a timber structure built above it lay at the eastern limit of the site. The spatial organization was precise and was maintained throughout the four decades of the site’s use. The cremations were mostly un-urned but may originally have been buried in fabric or leather containers. Careful analysis showed that only a proportion of the cremated bone had been collected from the pyre for burial.

Figure 20.12 The cremation cemetery at Westhampnett, West Sussex (source: Fitzpatrick 1997a).

The unusual completeness of the excavation and the array of features discovered allow something of the complexity of the rite de passage to be glimpsed: the initial arrival and laying out of the body (quite possibly in the ‘shrines’), the building of the pyre, the act of cremation, the collection of cremated bone, and its final interment. Each stage would have been circumscribed by ritual and quite probably controlled in various ways by the calendar (Fitzpatrick 1997, 236–41). The Westhampnett excavation provides a coherent set of data which allows the process of disposal to be modelled but it is as well to remember that there may have been much regional variation in systems of belief.

In summary, it may be said that the burial patterns recognizable in the British Isles were complex. Cremation rites in the old Bronze Age style continued over much of the country into the sixth or fifth century but thereafter three distinctive burial zones can be distinguished: in the west cemeteries of inhumations in cists were the norm; in Yorkshire inhumation in barrow cemeteries was common, while in the centre south excarnation and subsequent burial seem to have been widely practised. From the beginning of the first century BC the rite of cremation became established once again in the south-east of the country where cremation cemeteries, sometimes of considerable size, developed: beyond this zone, however, the traditional rites of the Middle Iron Age continued unaffected.

Superimposed upon this regional pattern and chronological development was a separate pattern reflecting the social status of the dead person. Status variations first become apparent among the Middle Iron Age burials of Yorkshire where a certain sector of society was afforded burial rite involving the deposition of a two-wheeled vehicle in the grave. Discrete sets of grave- goods were also used to indicate status and gender. By the beginning of the Late Iron Age these grave-sets (female burials with mirrors and male burials with weapons) are found sporadically in other parts of the country, indicating a change of practice. This was contemporary with, and may in part have been occasioned by, a change in burial rite in the south-east of Britain as social and economic contact with Belgic Gaul intensified. In this area the considerable variations in wealth that could occur in society were closely reflected in grave-goods ranging from the simplest unaccompanied cremation to the conspicuous display of wealth demonstrated by the burials at Lexden and Folly Lane.

Religious and ritual locations

The ritual foci favoured during the Iron Age can be divided into two broad categories: shrines incorporating some kind of man-made structure, and natural locations such as springs, streams or clumps of trees.

The clearest example of the few shrines at present known was found inside a ditched enclosure at Heathrow, Middx., along with a number of domestic buildings (Figure 20.13). The temple consisted of a central cella, defined by trenches in which timber uprights had been set, surrounded by an ‘ambulatory’ constructed of individual close-set posts, the whole building being little more than 10 m square. The similarity between this structure and the later Romano-Celtic temples is so striking that there can be little doubt of the Roman form being modelled upon pre- Conquest styles. At Stansted a rectangular structure occupying a central position surrounded by circular houses and enclosed in a rectangular ditched enclosure has striking similarities to the arrangement at Heathrow. Another rectangular shrine, similar in many respects to the Heathrow temple, has been uncovered towards the centre of the hillfort of South Cadbury, Somerset (Figure 20.13). The surviving part of the South Cadbury shrine is a small cella with an attached porch, comparable in size to Heathrow but apparently without the surrounding ambulatory. Its ritual connotations were further emphasized by the discovery of a number of animal burials in shallow pits lining the approach.

Figure 20.13 Temples and shrines (sources: Maiden Castle, Wheeler 1943; South Cadbury, Alcock 1970; Lancing Down, Bedwin 1981; Heathrow, Grimes 1961; Frilford, Bradford and Goodchild 1939; Stansted, Brooks 1993).

A group of buildings which may have served a religious function has been discovered within the hillfort of Danebury, Hants (Figures 20.13–20.15). One structure was closely similar to the cella of the Heathrow temple. Of the three other buildings which appear to have been associated with it, two were smaller, while the third consisted of a large square fenced enclosure: all were oriented in the same direction towards the entrance of the fort and were sited close to the main road, but no evidence of ritual activity was recognized.

The discovery of four examples of shrines within fortified enclosures raises the possibility that many of the hillforts and other major settlements may have contained defined religious foci, though the religious association of the buildings may not always be apparent. In Maiden Castle, Dorset, the building which is probably a shrine is a simple circular stone-walled structure lying at the end of one of the streets leading into the fort from the east gate (Figure 20.13). The only hint of ritual activity is an infant burial just outside the door, but the fact that the building was reconstructed in the Roman period alongside a rectangular Romano-Celtic temple is a strong indication of the religious continuity of this particular location. It raises the possibility that many of the Roman temples sited in hillforts may have been constructed on the sites of pre-Roman shrines.

Continuity of this kind is not restricted to hillforts. A sequence of structures almost identical to the Maiden Castle arrangement has been exposed at Frilford, Oxon., where a rectangular and a circular Roman temple were found to succeed an earlier religious centre, the circular Roman building lying above a penannular ditched enclosure of Iron Age date which contained a setting of six post-sockets (Figure 20.13). Evidently Frilford served as a ritual centre for some decades before the Roman invasion.

The same is probably true of the religious site on Lancing Down, Sussex (Figure 20.13), where a small rectangular building comparable to the smaller structures at Danebury was found close to a typical Romano-Celtic temple of later date. Direct structural continuity is unproven, but that the site was revered for its religious associations over centuries spanning the Iron Age and Roman period seems likely.

One of the most remarkable examples of religious continuity to be discovered in recent years is the temple on Hayling Island, Hants (Figure 20.16). The Iron Age complex, built in the second half of the first century BC, consisted of a circular structure set towards the centre of a rectangular courtyard enclosed by a palisade: both elements were closely reflected in the masonry rebuilding which took place in the second half of the first century AD. So close in plan and location were the two structures that there can be little doubt that the Iron Age building was still standing in some form at the time when the Roman builders moved in. The layer associated with the pre-Roman shrine produced a rich range of votive items including horse gear, spears, fragments of sword scabbards, brooches, tankards, currency bar fragments and almost 100 coins mainly of the Atrebates, Durotriges and Dobunni and from Continental Gaul. The collection provides a unique insight into the range of votive items thought to be appropriate to the unknown deity who was worshipped there.

Continuity is also probable at Harlow, Essex, where an Iron Age deposit associated with pits, post-holes and a circular structure was found beneath a Romano-Celtic temple. More than 230 Iron Age coins were found, many of which are likely to have been deposited in the pre-Roman phase. The numbers are sufficiently large to suggest the presence of a pre-Conquest religious sanctuary dating back to the first century BC. Similar evidence suggestive of continuity comes from a number of Romano-Celtic temples. For example at Worth in Kent a small group of model shields (Figure 20.17) must be indicative of Iron Age ritual activity but there is little else to indicate the form of the buildings, if any, which constituted the sanctuary. There is also evidence of Iron Age activity pre-dating the Roman shrine at Uley, Glos. In all probability, the continuity of temple locations between the Iron Age and Roman periods will prove to be widespread when the early levels beneath Roman structures are more fully explored.

Figure 20.14 Rectangular buildings, probably of a religious nature, in the hillfort of Danebury, Hants (source: Cunliffe 1984a).

Figure 20.15 The principal ‘shrine’, Danebury, Hants (photograph: Danebury Trust).

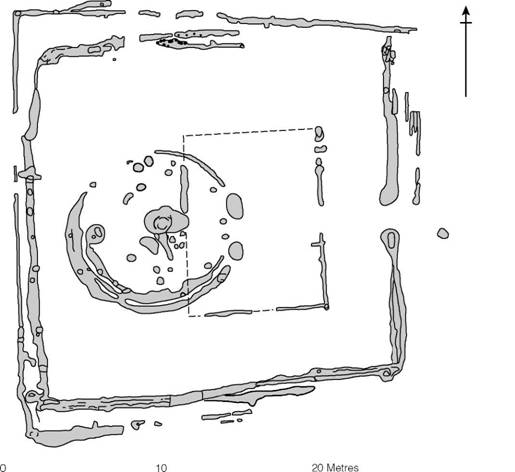

Finally we must mention the remarkable site of Fison Way, Thetford, Norfolk, excavated between 1980 and 1982. Here a series of hill-top enclosures, apparently domestic in origin, was replaced early in the first century AD by a double-ditched rectangular enclosure containing one centrally placed massive round building. The overall plan is not unlike Hayling Island though the Fison Way complex was on a much larger scale. This phase II structure was replaced, in phase III, by an even more startling arrangement comprising a large rectangular ditched enclosure containing five carefully sited circular buildings: the central structure is interpreted as being of two storeys. This inner enclosure is set concentrically within another rectangular ditched enclosure with the intervening space, of some 34 m, occupied by eight concentrically arranged trenches which the excavator interprets as bedding trenches for bushes or trees (Figure 20.18). The date of phase III is not closely defined but could lie within a decade on either side of the Roman invasion. The very remarkable nature of the plan and the virtual absence of contemporary domestic debris argue strongly for the site being a sanctuary.

Figure 20.16 The temple at Hayling Island, Hants (source: King and Soffe 2001).

Sacred locations and the natural landscape

Sacred locations unmarked by shrines must have abounded in Britain, as in the rest of the Celtic world. Springs, bogs and rivers would have been the obvious foci for ritual practices, as too would other striking natural features such as large rocks, very old trees or groves of trees. In all of these places the gods were thought to live, and there they had to be served or placated.

Direct archaeological evidence for such locations is seldom forthcoming but many of the items of metalwork recovered from bogs and rivers may well have been offerings deliberately dedicated to the spirits of the place (Fitzpatrick 1984; Wait 1985). The enormous numbers of exotic objects from the Thames (Figure 20.19) and the smaller, but no less impressive, collections from other rivers like the Witham and the Tyne probably originated in this way. Bog deposits are also relatively common in some parts of Britain; among these must be included the large collection of metalwork thrown into the lake at Llyn Cerrig-Bach on Anglesey, and the hoard of material, including two cauldrons, from Llyn Fawr in Glamorganshire. The pair of bronze ritual spoons from Crosby Ravensworth, Westmorland, the pony cap and horns from Torrs in Kirkcudbrightshire and the famous carnyx head from Deskford were also bog deposits. Besides the Llyn Fawr find, several other cauldrons from Britain, including an example from Feltwell in Norfolk, and others from Ireland, had been thrown into bogs. Tankards too were sometimes found in rivers and bogs, like the famous Trawsfynydd tankard from Merionethshire and the vessel from Shapwick Heath, Somerset. The metalwork from these locations is impressive not only in quantity but also for its very high quality. One can only suppose that a surprisingly high percentage of society’s wealth was dedicated to the gods in this manner.

Figure 20.17 Votive model shields from Worth, Kent (scale 1:3) (source: reproduced from Klein 1928).

It is quite likely that specific locations were chosen as the points from which the offerings were thrown into their watery contexts. At Llyn Cerrig Bach a natural rock provides a convenient platform but elsewhere specifically constructed walkways may have been built out into the water. The Late Bronze Age structure at Flag Fen may belong to this category, with votive offerings of metalwork being deposited from the Late Bronze Age to the Roman Conquest. Another structure discovered in 1981 in the valley of the river Witham at Fiskerton, near Lincoln, consisted of two rows of vertical timbers supporting horizontal boarding. Dendrochronological dates show that the timbers were renewed every sixteen to eighteen years between 457 and 317 BC. From this walkway a number of offerings were thrown into the water, including iron swords and spears together with a number of tools. It is not irrelevant that the famous Witham shield was found nearby in 1781. Structures like Fiskerton may have been quite common in the Iron Age landscape, allowing devotees to cross the liminal space between the land and water sacred to the gods.

Figure 20.18 The ritual site at Fison Way, Thetford, Norfolk (source: Gregory 1992a).

Finally, within the context of watery deposits we must consider the human body found in the bog at Lindow, Cheshire. The man had been hit violently on the head, been garrotted and had his throat cut before being consigned to the bog. It is tempting to see this as a ritual act and to remember, in this context, the tightly flexed skeletons found on the bottoms of the pits in Danebury and elsewhere in central southern Britain. Lindow man may differ from them only in that local burial conditions preserved his skin and hair, allowing the manner of death to be determined. In other words it is a distinct possibility that the sacrifice of human beings was widespread in pre-Roman Britain.

Figure 20.19 The Thames – a sacred river (source: Cunliffe 1993).

While the discovery of fine metalwork tends to pinpoint sacred places besides bogs or rivers, the sacred groves mentioned by the classical writers are more difficult to locate. Some help is, however, provided by the distribution of the Gallo-Britannic word nemeton, which means a sanctuary in a woodland clearing. The word occurs in several Romano-British place-names in different parts of Britain, such as Vernemeton near Leicester, Medionemeton in southern Scotland, and Nemetostatio near North Tawton in Devon (Griffith 1985). The Roman name for the thermal spring at Buxton, Aquae Arnemetiae, also includes the element nemet-, suggesting that the spring was in use as a religious centre long before the invasion. That so many nemeton elements are incorporated in Roman place-names of Britain is an indication of the large numbers of sacred woodland clearings of pre-Conquest date, the memory of which lingered on.

One possible contender for the title of nemeton is Snettisham in Norfolk where a number of discrete ‘hoards’ of gold, silver and electrum torcs, coins and other scrap precious metals have been unearthed over the years since the first discovery was made in 1948. In 1991 a large polygonal enclosure ditch was discovered enclosing 8 ha within which all the ‘hoards’ were located. Although the ditch dates from the Roman period it could well be that it was laid out as the temenos boundary of the religious place which may indeed have been a sacred grove. Such issues are difficult to test archaeologically.

The deposition of valuable goods in rivers, bogs, springs or groves would have been undertaken within the context of an intricate pattern of religious beliefs now entirely beyond reconstruction. All we can safely surmise is that the rites would have involved some element of propitiation – the thanking of the deity for support in some enterprise or in anticipation of divine intervention in the future. Similar acts probably pervaded Iron Age life.

Propitiation and belief within the home

In the late 1970s it became clear, from the large-scale excavations at the hillfort of Danebury, that recurring patterns of deposition could be recognized when comparing the contents of disused storage pits, enabling consistent behaviour to be distinguished from casual rubbish disposal. Thus the articulated leg of a horse found on the bottom of one pit is relatively meaningless but when found six or seven times in a sample of 200 pits it becomes a ‘behaviour pattern’. This recognition, and the very large number of storage pits excavated, encouraged a detailed analysis which has thrown much light on ritual behaviour within the settlement (Grant 1984, 533–43; Cunliffe 1992, 1995, 80–8; Poole 1995, 249–75). These observations and their implications have been widely accepted and have been examined across a broader range of sites (Hill 1995a; Cunliffe 2000, 128–34).

The evidence from Danebury and from contemporary sites excavated in Hampshire has amply demonstrated that, within the fillings of storage pits, complex systems of deposition were in operation involving animal carcasses, whole or in joints (Figure 20.20), human bodies or body parts, groups of pots and sets of artefacts. These are the archaeologically recognizable component of a behaviour pattern which may well have required a range of products, including perhaps cheese, hides, bales of wool, etc., to be placed, usually on the bottoms of storage pits, after they had ceased to be used for their primary purposes. In a significant number of cases secondary and sometimes tertiary deposits were made in the same pit, after intervals of erosion, before the pit was finally abandoned.

Explanations of such behaviour are necessarily speculative but if, as seems highly likely, storage pits were used to keep seed grain during the period between harvest and sowing, then it would not be unreasonable to see the special deposits as propitiatory offerings to the chthonic deities, who were perceived to have guarded the grain during the liminal period of its dormancy, and to ensure subsequent fertility. In some such context the secondary and tertiary deposits could also be explained as reflecting rituals associated with a successful harvest and the beginning of a new cycle of storage. This might also offer an explanation for the use of storage pits which might seem to be an unnecessary way to store seed when perfectly serviceable above- ground granaries were also in use. By digging a pit into the realms of the underworld and placing seed corn in it the community might have been deliberately placing its vital seed in the safe-keeping of the chthonic gods. There are many resonances here with Indo-European fertility beliefs perhaps best known through the myths of Demeter and Persephone (Cunliffe 1992). How widespread such beliefs and practices were in the British Isles it is difficult to say but the underground storage structures of Cornwall (the fogous) and of Scotland (the souterrains) may reflect aspects of the same beliefs.

Figure 20.20 Propitiatory offering of a dog and a horse leg in a pit at Danebury, Hants (photograph: Danebury Trust).

The concept of fertility must have been central to the concerns of Iron Age communities and it is highly probable that the beneficial effects of fertilizing the fields, by direct animal manuring and the spreading of midden waste and marl, would have been understood and widely practised. Such regimes would, no doubt, have been enacted within strict religious control. Thus the huge midden deposits at Potterne, East Chisenbury and elsewhere may have been, in part, ritual accumulations reflecting the power of fertility. Similarly the extensive evidence which has come to light for the quarrying of chalk, often by opening out existing ditches, reflects the use made of chalk for marling the clayey soils capping the chalk downs. The burial of human remains within these chalk quarries may be another deliberate act in the fertility cycle (Cunliffe 2000, 130–2).

Other aspects of propitiation may also be recognized from time to time on settlement sites. The deposition of hoards of ironwork presents an easily identifiable practice. Hingley (1991) has pointed out that iron currency bars are often associated with settlement boundaries while at Danebury the four hoards of ironwork recovered were all found under the floors of houses, suggesting a very deliberate pattern of deposition, the iron ‘offering’ perhaps ensuring the well-being of the occupants (Cunliffe 1995, 86). Beliefs, and the ritual acts which sustained them, must have pervaded every aspect of daily life. We will return to other aspects of this theme later (pp. 576–8).

Druids and the gods

The intermediaries acting between the people and the gods in Britain, as in Gaul, were the Druids. Caesar believed that Druidic religion originated in Britain, whence it was introduced to the Continent: ‘Even today’, he says, ‘anyone who wants to make a study of it goes to Britain to do so’ (BG VI, 14).

The Druids served Gaulish society in various ways: they were responsible for administering and guiding the religious life of the people, supervising ceremonies and sacrifices, and divining the future from such omens as the death struggles of a sacrificial victim. They also maintained the theory and practice of the law and were the teachers of the old oral traditions of the people, holding schools where the novices learnt verses off by heart. Caesar reports:

They seem to have established this custom for two reasons: because they do not want their knowledge to become widespread and because they do not want their pupils to rely on the written word instead of their memories; for once this happens, they tend to reduce the effort they put into their learning.

(BG, VI, 15)

The literary evidence relating to the Druids can frequently be used to enhance and explain the archaeological material. Belief in the afterlife, which is demonstrated by the provision of grave- goods with the dead, is referred to several times. Caesar says that the one idea that the Druids wanted to emphasize above all others was that souls do not die but pass from one body to another as each body dies. Pomponius Mela, writing in the first century AD, elaborates on this belief: because of their very strongly held views on the afterlife, he says:

they burn and bury with their dead the things they had owned while they were alive. In the past they even used to put off the completion of business and the payment of debts until they had arrived in the next world. Some even went so far as to throw themselves willingly on to their friends’ funeral pyres in order to share the new life with them.

(Place of the World, iii, 19)

A firm conviction about immortality was of particular encouragement to those required to act bravely in battle, as several classical writers were quick to point out.

Pomponius Mela writes of Druids teaching in caves or inaccessible woods, while Tacitus mentions ‘groves devoted to Mona’s [Anglesey’s] barbarous superstitions’, implying that at these places human sacrifice was carried out. An altogether more gentle ritual is, however, described in some detail by Pliny the Elder. The passage is worth quoting at length because of the insight it gives into ritual beliefs and practices which would otherwise be unrepresented in the archaeological record.

They choose groves of oak for the sake of the tree alone and they never perform any sacred rite unless they have a branch of it. They think that everything that grows on it has been sent from heaven by the god himself. Mistletoe, however, is very rarely found on the oak and, when it is, it is gathered with a great deal of ceremony, if possible on the sixth day of the moon… They choose this day because, although the moon has not yet reached half-size, it already has considerable influence. They call the mistletoe by the name that means all-healing.

(Nat. Hist., XVI, 249)

He goes on to describe the cutting of the mistletoe with a golden sickle by a white-robed Druid, followed by the ritual sacrifice of two white bulls, and concludes: ‘They believe that if the mistletoe is taken in a drink, it makes barren animals fertile, and is a remedy against all poison’. Later Pliny mentions other herbs which, if collected under certain conditions, possessed curative properties: selago (or sabine) warded off evil and could cure eye diseases, while a marsh plant, samolus, was regarded as a charm against cattle disease. Mistletoe, selago and samolus are just three which Pliny happens to note but hundreds of other herbs must have been endowed with medicinal properties about which the Druids would have known and taught.

Many of the classical accounts refer to the Druids carrying out human sacrifice, and that ritual killing may well have an archaeological reality has been suggested above (pp. 568–9). Ritual killing for the purpose of augury is mentioned by Diodorus Siculus and Strabo, while the mass sacrifices of men and beasts, burnt to death in cages made of branches, are described in some detail by Caesar and Strabo. Strabo also records ritual deaths by archery and crucifixion, and Tacitus, describing the destruction of the Druid centre on Anglesey in AD 59, justifies the Roman attack by saying of the Druids that ‘it was their religion to drench their altars in blood of prisoners and consult their gods by means of human entrails’ – words calculated to conjure up a sense of horrified distaste among his sophisticated Roman audience. One wonders whether the partly dismembered child from Wandlebury, the human limbs and torso from the ‘ritual pit’ at Danebury or the man buried in the bog at Lindow were in any way connected with Druidic practices. The only other archaeological evidence for ritual is the decapitation of bodies, like those found at Bredon Hill, Worcs., and the setting up of heads on gates as witnessed by the skull found near the entrance to the Stanwick fort in Yorkshire. Decapitation is, however, more likely to have been a normal part of the battle scene than the preserve of the priestly cult.

The Druids mediated between men and their gods, of whom there were many. Caesar gives the clearest picture of the Celtic pantheon by equating the native deities with their nearest Roman counterpart (BG VI, 17–18): ‘Their main god’, he says, ‘is Mercury; they have many images of him. They consider him the inventor of all arts, the god of travellers and of journeys and the greatest god when it comes to obtaining money and goods.’ He then goes on to describe the lesser gods: Apollo who wards off disease, Minerva presiding over work and art, Jupiter the ruler of the heavens, and Mars the god of war. ‘When they have decided to go to battle, they generally promise the captured goods to Mars. When they are victorious, they sacrifice the captured animals and make a pile of everything else.’ As we have suggested above, perhaps some of the ritual deposits from rivers and bogs were votive dedications made to the gods in thanks for victory.

Figure 20.21 Boat with figures from Roos Carr, Holderness (photograph: Hull Museum).

Iconography

There are few indisputable representations of gods or men from pre-Roman Iron Age contexts in Britain, but wooden figurines from Roos Carr, Holderness (Figure 20.21), Kingsteignton, Devon, and Ballachulish, Argyllshire, are all of first-millennium BC date and provide a valuable reminder of a facet of religious behaviour which was, in all probability, widespread in Britain, and may perhaps be compared with the votive offerings found in considerable numbers at sacred locations in Gaul, usually associated with water. Radiocarbon dates suggest that Ballachulish may be the oldest, dating from the seventh to fifth centuries; Roos Carr is a little younger, dating to the sixth century, with Kingsteignton belonging to the fourth to third centuries (Coles 1990).

Stone carvings are equally rare in Britain, but the work at Garton Slack, and elsewhere in Yorkshire, has produced a group of remarkable chalk figurines (Stead 1971b, 1988; Brewster 1976). The figures (Figure 20.22), averaging about 13 cm high, were usually wedge-shaped, with simply moulded heads which in most cases had been broken off. No attempt had been made to show legs, but arms were indicated by incisions and shallow carving, and several of the figures were shown to be wearing belts and swords. In addition to the human figures a model of an oval-shaped shield was recovered. While most of the objects were without a clearly defined context, one was found under archaeological conditions stratified in the ditch of a rectangular ‘ritual enclosure’ which formed part of a religious and burial complex. There can, therefore, be little doubt that the figurines should be regarded as some kind of votive offering.

Figure 20.22 Stone figurines from North Humberside: 1 Wetwang Slack; 2 Withernsea; 3 Garton Slack; 4 uncertain; 5 Malton (North Yorks.) (source: Stead 1988).

The rarity of monumental stone carving in Britain, in the style of the stelae of Brittany and the pillars of the Rhineland, deserves noting since it implies a significant difference in attitude to religious symbolism. There are, however, two fragmentary stone pillars from Trefollwyn, Anglesey, which might reasonably be claimed to be of Iron Age origin.

The iconography of Britain before the Conquest, reflected largely in the Roman formalization of the situation, shows that an immense number of local or tribal gods existed, each known by a regional name and each endowed with specific qualities. Caesar’s broad summing up, linking the Celtic deities to their nearest Roman counterpart, was little more than rationalization of an exceptionally complex and bewildering pattern. After the Roman Conquest the gods were frequently depicted in various guises, sometimes as a disembodied head, which must have represented a generalized portrait of divinity, and sometimes with specific characteristics. One of the more common types is the horned god which, depending upon his attributes, might variously represent the war-god Cernunnos (as Mars), Mercury, who Caesar says was the most commonly illustrated, or sometimes the hunting god Silvanus. Among the female deities the old triad of mother goddesses frequently occurs, particularly in the north and west, reflecting a deep-seated traditional belief in the power of three, a belief further emphasized by the occasional discovery of triple-faced heads.

Besides sculptural representations, the old gods are often named on dedicatory altars and other inscriptions. The names might include tribal deities like Brigantia or more widely respected gods like Camulos, the powerful war-god, whose shrine probably lay in the defended area at Camulodunum – perhaps at the site of Gosbecks Farm, an important cult centre in the Roman period. Other gods were more specific to certain localities, like Sulis who, later paired with Minerva, presided over the sacred spring at Bath, whereas others possessed more prescribed skills: Taranis the thunder-god or Nodens the cloud-maker. Some deities were rather more generalized in their stated powers: Nemetona and Mars Rigonemeta were respectively the goddess and god of the sacred grove, while Leucetius was simply ‘the shining one’.

The list of gods is very long: each tribe must have had its own pantheon of favourite deities and every one of the many thousands of sacred locations would have been the special preserve of a local god whose name and presence would have been part of the natural awareness of the local community. It would have been difficult to travel far in Iron Age Britain without coming into contact with some sign of the gods, for religion and superstition pervaded all aspects of pre- Roman life.

Space, place and time

Boundaries, particularly those which define habitation or assembly sites, are most likely to have been endowed with power, and their creation and maintenance will have been embedded in ritual (Hingley 1990). Since an enclosure boundary separates outside from inside, and in doing so bounds the behaviour appropriate to the two zones, the liminal spaces between them – the entrances – will have been particularly potent and subject to many taboos. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that entrances often showed evidence of elaboration and of many phases of renewal. While such works may have resulted from practical necessity – the requirement to repair and redefend – it is highly probable that acts of renewal carried with them a deeper symbolic meaning. A settlement like Gussage All Saints in Dorset, with its substantial gate and spacious front forecourt, was constructed to focus on the act of assembly and procession into the enclosure. The enclosure ditch itself, especially away from the gate, was little more than symbolic.

The act of procession may also have been the reason why many of the early hillforts (like the late Neolithic henge monuments before them) had two ‘entrances’ opposed to each other. They allowed passage through the enclosure and may well have served as entrance and exit each with its own distinct function. The blocking of one of the entrances, which seems to have been a widespread phenomenon in central southern Britain at the end of the fourth century, must have represented a major reorientation in behaviour and may have been only one aspect of a widespread social dislocation experienced at this time.

The excavation of Danebury, Hants, raises a number of questions about the significance of hillfort boundaries which have traditionally been considered principally in terms of military imperatives. Sections through the so-called counterscarp bank on the outer lip of the ditch showed that it had been gradually built up over a considerable period of time by a number of thin deposits derived from clearing out the ditch. At one point eleven distinct layers could be identified with evidence of weathering between. What we are observing here is the regular clearing of the ditch perhaps every five to ten years. The periodicity of the work would seem to imply an act of renewal determined more by ritual than by sudden need. The main rampart was subject to two phases of ‘rebuilding’, the second of which was contemporary with the blocking of the gate. In neither case did the addition of material to the back of the rampart improve the defensive capability of the rampart. At best they added a clean layer of gleaming white chalk to the inner rampart face. Here again it is more than likely that this represents an act of renewal, related to some major event in the life of the community. After the second renewal in the early third century buildings occupied the area immediately behind the rampart. Here it was possible to identify eight phases of extensive rebuilding. If each phase was of approximately equal duration this would imply rebuilding every twenty years or so – a periodicity which may be linked to changing generations or to lunar cycles. While it must be admitted that all of these observations could be explained in purely practical terms it is quite possible that the three sequences of renewal were controlled by behavioural cycles embedded in the belief systems of the society. There are ample examples in the recent ethnographic past to show that processes of this kind were widespread in the world. Life in the Iron Age would undoubtedly have been circumscribed by behavioural rhythms of this kind.

It is a reasonable assumption that Iron Age communities understood the passage of time and used celestial phenomena to create a calendar based on the solstices and the equinox (Fitzpatrick 1996, 1997b; Parker Pearson 1999). These fixed points in the year, marked by ceremonies and by feasting, would have divided the tasks of the agro-pastoral cycle signalling the onset of new activity and a change of pace (Figure 16.5). It is even possible that the propitiatory offerings we have noted in the storage pits were deposited on such occasions. Annual cycles, suitably recorded, may in aggregate have created longer cycles controlling acts of renewal of the kind seen at Danebury. These are speculative matters difficult to test but the speculation is quite within the realms of possibility.

One interesting observation, which has some bearing on these issues, is the recognition that a high percentage of Iron Age roundhouses are oriented with their doorways to the south-east with a particular emphasis on the direction of the midwinter sunrise (SE) and the equinox (E) (Oswald 1997). While there are some practical advantages in this, in terms of shelter from prevailing winds and gaining early light and warmth from winter sunrise, it may well be that the direction was deliberately chosen to orient the house with a propitious celestial alignment. The argument has further been developed by suggestions that the alignment, passing through the doorway, was perceived to divide the house into two parts, each reserved for specific activities (Fitzpatrick 1997a; Parker Pearson 1999). It is highly probable that the interior spaces of houses were understood to be carefully structured so as to contain behaviour, but little compelling evidence of this has yet been found for the Iron Age.

The question of structured space is an interesting one and we may assume that all enclosed places were governed by rules and taboos which demanded that different activities were performed in designated, but not necessarily physically demarcated, zones. These were no doubt defined in terms of the sun (sunrise and sunset), by axis of entry (left- or right-hand), or by other, less obvious, relational attributes. Occasionally there are hints of these patterns in the deposit of midden material (Parker Pearson, Sharples and Mulville 1996) or by the relationships of different kinds of buildings (Cunliffe 1995, 20–6) but patterns of behaviour that undoubtedly governed people’s lives are still archaeologically elusive.