“Those who were hired to protect patients from snake pit conditions in the ’70s are now working to prevent treatment. The result is that walking around naked and psychotic—in or outside a hospital—has moved from a condition to be deplored to a right that is being defended.”

—Jay, hospital worker

THE INDUSTRY OPPOSES PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITALIZATION

Some seriously mentally ill need hospitalization but can't get it because the United States is short at least ninety-five thousand beds.1 This is largely because the Institute for Mental Disease (IMD) Exclusion in Medicaid prevents states from receiving reimbursement for long-term hospital care of adults with serious mental illness. You would think the mental health industry would oppose this blatant form of discrimination as it only applies to the mentally ill. Wrong. The industry opposed congressional efforts led by Representative Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX) and Representative Tim Murphy to increase the number of beds, and is also fighting state-level efforts to increase beds.2

They are bringing suits to force states to empty hospitals, an activity that mental illness advocate Pete Earley contends could be creating a new era of disastrous deinstitutionalization.3 Pennsylvania consumer leader Joe Rogers told an interviewer, “We don't need Haverford [psychiatric hospital]. We don't need Norristown [psychiatric hospital]. We don't need any of the state hospitals.”4 Georgia's Grady Hospital is so overcrowded that “psychiatric patients may wait days to be transferred to a bed, lying on gurneys without treatment.”5 But Bazelon legal director Ira Burnim argues, “Georgia is the primary example of a system where the problem is way too many hospital beds and too much money spent on hospitals.” Advocates claim New York hospitals should be closed because California has only five hospitals and Texas eight, compared with New York's twenty-four. But in California, the mentally ill are almost four times as likely to be incarcerated as hospitalized. In Texas, it's eight times.6

The mental health industry views hospitals as a bank account, and it wants to make a withdrawal. It wants the money that comes from closing the hospitals and selling the land to go to them, a process they call “reinvestment.” But community programs largely refuse to serve the seriously ill individuals who are being discharged from hospitals.7 When New York governor Andrew Cuomo proposed closing psychiatric hospital beds, the state trade organizations, Mental Health America and the New York Association of Psychiatric Rehabilitation Services (NYAPRS) praised the closings.8 NYAPRS hyperbolically wrote that the existence of hospitals is “essentially forcing people to remain institutionalized.”9 But the same two organizations oppose Kendra's Law, New York's assisted outpatient law that would require their members to serve the seriously ill.

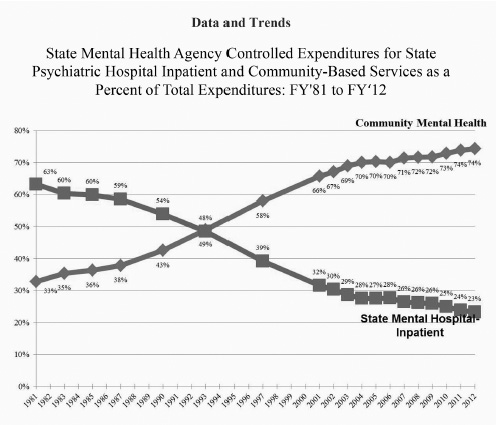

As the chart in Fig. 11.1 shows, in 1981, almost two-thirds of state mental health agency controlled expenditures for mental health were devoted to psychiatric hospitals that by definition serve the most seriously ill, and one-third of spending went to those in the community. By 2012, it was reversed. Inpatient spending was only 23 percent of state-controlled spending, and community care represented 74 percent. The number of people treated in the community rose proportionately as did the number and percentage of persons with mental illness who are incarcerated. This chart belies the mental health industry claim that too much is spent on hospitals.

The industry would have us believe that psychiatrists send too many to hospitals too easily.10 But Associate Professor of Law Amanda Pustilnik was right when she wrote,

Far from forcing people into treatment, psychiatrists every day face hard choices about who to force out of treatment: People who need and want help must be discharged due to lack of hospital space. People with major mental illnesses like psychosis and schizophrenia seek help at hospitals but are routinely turned away because the few available beds must be reserved for the handful who are truly dangerous. Getting out of psychiatric hospitals is occasionally hard for some people. Getting into them is hard for everyone.11

Fig. 11.1. This chart prepared by the trade association for state mental health commissioners shows how state mental health commissioners moved funds from hospitals that served the most seriously ill to community services for the less seriously ill.

Source: Joe Parks and Alan Q. Radke, eds., The Vital Role of State Hospitals, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) (Alexandria, VA: NASMHPD, July 2014), http://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/The%20Vital%20Role%20of%20State%20Psychiatric%20HospitalsTechnical%20Report_July_2014(1).pdf (accessed July 14, 2016).

The industry argues that we shouldn't return to the days of yore when people were indiscriminately committed to wretched institutions. I agree. Everyone agrees. In fact, it is a strawman. The opposite is true. The lack of hospitals is the reason people are thrown into wretched institutions, specifically jails and prisons, a process called, “transinstitutionalization.”

There is an inverse correlation between the number of hospital beds available and the number of mentally ill incarcerated.12 Industry efforts to decrease the former are increasing the latter. As a result, sheriffs who run the jails are standing up for hospitals:

• In Minnesota, Muskegon County sheriff Dean Roesler noted that closing the state's psychiatric hospitals “created absolute chaos as far as the criminal justice system…. There is a failure in the mental health system.”13

• In Illinois, Cook County sheriff Tom Dart told 60 Minutes, “There is no person who could argue otherwise that the jails and prisons are not the new insane asylums. That's what we are. And the irony's so deep that you have a society that finds it wrong to have people warehoused in a state mental institution, but those very same people were OK if we warehouse ’em in a jail—you've got to be kidding me.”14

• In Iowa, Wapello County sheriff Mark Miller noted that the state's plan to close psychiatric hospitals was staggering, observing that “the shortage of inpatient hospital units means that too many people with mental illness are stuck in jails like the one he runs in Ottumwa.”15

In some states sheriffs are opening mental health wings in jails or forcing state psychiatric hospitals to increase their forensic capacity.16 The mental health officials often accomplish this by taking beds from non-forensic populations and allocating them to those who come via the criminal justice system, further exacerbating the shortage.

Historically, hospitals controlled and medicated dangerous patients until the danger passed and the patient could be safely released. That's harder to do these days. “Advocates” now work to prevent hospitals from using violence-reducing restraints, seclusion, and involuntary medication.17 As a result, hospitals now call the police when a patient becomes violent and send that person to jail. Patients “protected” by advocates are turned into prisoners.

Bob had schizoaffective disorder and stayed well and hospital-free on medications but did poorly when off. Despite this, his treatment provider took a dim view of medicine and took him off. As a result, he was “evicted from his apartment, banned from an area grocery store, repeatedly hospitalized, and arrested twice—the first time for assaulting a male nurse at Rutherford Hospital, the last for breaking and entering into a stranger's home” and is now incarcerated.18

THE INDUSTRY IS BIASED AGAINST MEDICATIONS

As discussed in chapter 6, side effects notwithstanding, medications remain the single best way to ameliorate symptoms and prevent many people with serious mental illness from becoming homeless, suicidal, arrested, violent, and incarcerated. Some won't take them, and they don't work on everyone, but when they do, no other treatment does as well. The industry ignores this. Rather than admit to the importance of medications for those with serious mental illness, it focuses on the problems with them and tries to limit their use.

Scientology and its Citizens’ Commission on Human Rights (CCHR) are two leading anti-medication advocates. They may be outside the mainstream, but not by much. Directors of the SAMHSA-funded National Empowerment Center and the SAMHSA-funded Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation both sit on the board of the Foundation for Excellence in Mental Health Care (sic) that funded MindFreedom, an organization that claims that “the long term effectiveness of psychiatric medications has not been demonstrated.”19 The National Empowerment Center website lists multiple resources on how to go off medications and none about the benefits.20 In 2003, CCHR and other organizations succeeded in having dire “Black Box” warnings put on antidepressants. A 2014 study found that these “decreased antidepressant use, and there were simultaneous increases in suicide attempts among young people.”21

Robert Whitaker has developed a cult-like following within the SAMHSA-funded antipsychiatry community by writing books and giving speeches focused on the side effects of medication that barely mention their efficacy.22 Whitaker's work has been widely criticized by medical experts.23 Anti-medication advocates claim the following:

• People who went off medicines did better than those who stayed on. The advocates failed to consider that those who stayed on may have stayed on because they were sicker. To them, the fact that people on, say, chemotherapy are sicker than those not on chemotherapy is proof that chemotherapy doesn't work.

• Because medications change brain structure, they are harmful. But medication-related changes in brain structure may explain why they are effective. They also fail to acknowledge that some brain structure changes appear in people with mental illness who are never medicated.24

• Schizophrenia medications reduce life expectancy. But research shows that those on appropriate doses of antipsychotics live longer than those who are not.25

If anti-medication advocates differentiated more forcefully between the worried well, who may not need medications, and the seriously mentally ill who often do, their arguments would ring closer to the truth.

Sheila, an activist with schizophrenia, attended a conference where Whitaker was speaking and remembers his message that healing can be done without meds. “I thought this was very dangerous rhetoric spoken to a roomful of consumers of mental health services needing to take medications.”

When a SAMHSA staffer tried to stop a SAMHSA-funded Alternatives Conference from teaching people how to go off medications and from having a speaker at a plenary session teach the evils of medications, she herself was reported to have been stopped by then SAMHSA administrator Pam Hyde, who greenlighted the anti-medication programming.26

THE INDUSTRY FIGHTS THE USE OF ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY

As described in chapter 6, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) can be a very beneficial treatment for the most seriously ill, especially individuals who have not been helped by other treatments. But parts of the mental health industry, siding with Scientology's Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR) work to limit access to it. They circulate the negative Hollywood portrayal of it that appeared in One Flew Over the Cuckoo Nest and position that as reality today. They refuse to use the medical term “electroconvulsive therapy” and substitute the loaded word “shock,” often combining it with “force.” They note that the results of ECT may not last, without explaining that neither do the results of medications if you stop taking them, or that sometimes ECT does result in permanent remission.

Peer pressured to stop taking medications

Iris Loomknitter, an advocate for people with serious mental illness who lives near LaCrosse, Wisconsin, and has several different mental health diagnoses, sent me a note complaining about the anti-medication bullying by SAMHSA-funded consumers:

There is too much prejudice against those of us who take psychiatric medications: It needs to stop! For example, when some people say that our psychiatric medications “turn people in to zombies,” it hurts we who take the psychiatric medications! Call it “stigma” if you want to. I call it prejudice. It is spreading cruel, ignorant lies! It is a form of fear mongering.

I have experienced this: anti-medication people who tried to frighten or convince me to not take my life-saving psychiatric medications. However those same anti-medication people could not “handle” my past suicidal, extremely needy, severely depressed or mixed bipolar episodes. They expected me to use my will power and/or ineffective “natural remedies,” which did nothing to help me. When nothing they offered helped me, they turned on me and shamed and blamed me, calling me horrible names like “energy drain” and “energy sucking!” I am not suicidal now, because I am on the right psychiatric medications.

Yes, anti-medication people have freedom of speech, but I also have the freedom of speech to warn people against them and to write against their counter-productive beliefs. Anti-medication people tend to take any negative side effects of prescription, pharmaceutical psychiatric medications and try to convince very sick people to avoid and to not take any medications at all! My psychiatric medications don't make me a “zombie!” Comments like that HURT!

In 2015 and 2016, when the FDA wanted to make ECT more widely available, the National Coalition for Mental Health Recovery and many of its SAMHSA-funded member organizations circulated a petition ginned up by a radical anti-treatment group to protest. The petition claimed, “Psychiatric labels are not actual medical diagnoses,” “Most psychiatric drugs are ineffective,” and “There is no situation that qualifies as an ‘emergency.’”27 Mental Health America (MHA) ignores the science on the efficacy and instead provides information on the “controversy” that CCHR and antipsychiatrists purport exists.28 As a result of industry and Scientology challenges to the use of ECT, it is hard to access. In the state of New York, few state psychiatric hospitals even have the device. If a patient at a hospital without an ECT machine needs ECT, she would have to be discharged from the hospital, transportation arranged to the hospital with the equipment, someone would have to sit with the patient, get her admitted to the new hospital, and then transport her back to the original hospital to be readmitted. This would have to be done for every course of the treatment. As a result of impediments like that to the use of ECT, it is rarely available to people without financial resources but is often used by the wealthy who have more choices. Kitty Dukakis, wife of 1988 Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis, wrote Healing Power of Electroconvulsive Therapy, based on her experience with it. Actress Carrie Fisher wrote Shockaholic describing her experience and how she wished she had tried it earlier. Talk show host Dick Cavett told People magazine his ECT treatment was “miraculous.”29 Roland Kohloff, former lead timpanist of the New York Philharmonic orchestra told the New York Times, “What I think it did was to act like a Roto-Rooter on the depression.”30 It is mind-boggling that the same peer groups that claim consumers should have “choice” in which treatments they choose work to make sure consumers can't choose ECT.

Not only does the mental health industry impede access to effective treatments, but it also encourages the use of ineffective treatments. How they do that is discussed in the next chapter.