P. Cornelius P. f. Lentulus Marcellinus Cn. Cornelius L f. Lentulus Pacifying the Roman world was still a work in progress. The Conscript Fathers accepted the fact that there were still regions of the world ‘that had need of a military guard’ and, unhesitatingly, they granted Augustus imperium for five more years to continue the work.1 Certain powers were also granted to Agrippa to match those of the princeps for five years.2 Augustus is reported by Dio as having remarked at the time that the interval – called a lustrum – would be long enough for them to carry out their duties.3

Augustus embarked on another purge of the Senate.4 He could not take chances with the body’s composition. Not only did he need to be sure he had enough members to support his legislative programme, but he also required a wide bench of talent from which he could choose his future provincial and legionary legates. Many senators were upset by the proposed reduction in membership and some even refused to resign.5 Undaunted, the princeps set up a board of thirty commissioners to select the best men by lot, but ways were soon found to circumvent the process and affect the supposed randomness of the results.6 One senator, Licinius Regulus, was particularly incensed at being struck off when, in his opinion, other less-qualified men – including his own son – still retained their seats. In a dramatic protest he ‘rent his clothing in the very Senate, laid bare his body, enumerated his military campaigns, and showed them his scars’.7 Recognizing mistakes were being made and that talented men were being lost to chance or corrupt practice, Augustus intervened; he picked candidates himself and, while letting others go, allowed many who had been disbarred to return to the House.8

His mishandling of the selection process deeply offended many, to the extent that some, as before, contemplated committing murder. Augustus had become increasingly concerned about attempts on his life and had already taken to wearing a cuirass or mail shirt underneath his tunic as a precautionary measure, even when he attended sessions of the Senate.9 Plots to assassinate Augustus and Agrippa were, allegedly, discovered.10 Executions followed in a few cases.11

| C. Furnius C. f. | C. Iunius C. f. Silanus | |

| suff. | L. Tarius Rufus |

It was the long-established tradition that, after battle, a victorious commander retained the larger share of the captured plunder (praeda) – baggage, cash, precious artifacts and enslaved prisoners of war – of the defeated enemy and dispersed a portion among their troops as he pleased. 12 The promise of booty was one of the reasons men went on campaign.13 Augustus sought to channel some of the rewards of conquest conducted in his name for the public good and, this year, ‘commanded those who celebrated triumphs to erect out of their proceeds (ex manubiis) some monument to commemorate their deeds’.14

In the last week of May, heralds wandered the streets of Rome inviting the citizens to a once-in-a-lifetime’s spectacle. The Ludi Saeculare (games held at 110-year intervals, then reckoned to be the maximum length of a man’s life) were to be presented.15 The last ‘Century Games’ had been hosted in the 140s BCE, but at Augustus’ insistence they were scheduled for this year, with the consent of the Senate.16 On 31 May, as its magister or director, Augustus led the members of the Quindecemviri Sacri Faciundis (charged with consulting the Sybilline Books (Libri Sybillini) of prophecy for Rome) in a distribution to the People of items of torches, brimstone and pitch used for ritual purification. After sunset, beneath a full moon, the Commission of Fifteen Men and guests gathered on the Campus Martius: C. Sentius Saturninus, M. Claudius Marcellus Aeserninus, M. Fufius Strigo, D. Laelius Balbus, M. Agrippa, L. Marcius Censorinus, Q. Aemilius Lepidus, Potitus Valerius Messalla, Cn. Pompeius, C. Licinius Calvus Stolo, C. Mucius Scaevola, C. Sosius, C. Norbanus Flaccus, M. Cocceius Nerva,

M. Lollius, L. Arruntius, C. Asinius Gallus, Q. Aelius Tubero, C. Caninius Rebilus and M. Valerius Messalla Messalinus.17 Members of this élite college had helped Augustus acquire or renew supreme power, at various times governed his provinces and commanded his armies. Sacrifices were offered to the ancient Moerae, hymns were sung, a theatre piece was performed and a special banquet was laid on.

The Games would last three days. On 1 June, the pageant officially began. Sacrifices were offered to Jupiter Optimus Maximus and games were held for Apollo and Diana. On the second day there were sacrifices to Juno Regina and the Magna Mater. On the third and final day, in the climax of the celebration, a choir sang a hymn specially written and scored for the occasion by Horace. In this ‘Poem of the Century’ (Carmen Saeculare), the voices of twenty-seven boys and twenty-seven girls filled the precinct of the Temple of Apollo, addressing him alone of the pantheon:

God, grant to our sons unblemish’d ways;

Grant to our old an age of peace;

Grant to Romulus’ race power and praise,

And large increase!18

The poet wrote of how, with the Sun god’s blessing, Rome’s enemies were now vanquished:

Now Media dreads our Alban steel,

Our victories land and ocean o’er;

Scythia and India in suppliance kneel,

So proud before.

Faith, Honour, ancient Modesty,

And Peace, and Virtue, spite of scorn,

Come back to earth; and Plenty, see,

With teeming horn.19

In a crescendo, the young voices appealed to the god to continue to promote the Romans’ well-being through eternity:

Lov’st thou thine own Palatial Hill,

Prolong the glorious life of Latium and Rome

To other cycles, brightening still

Through time to come!20

The Games triumphing the Roman achievement concluded. The crowds dispersed, buoyed by the inspirational themes of the evening, and abuzz with stories they would one day tell their grandchildren.

On a day sometime between 14 June and 15 July, Augustus adopted Agrippa’s two sons with the full consent of their father. 21 The older boy, just weeks from his third birthday, would assume the name C. Iulius Caesar Augustus filius, and his brother – barely a year old – would become L. Iulius Caesar Augustus filius. The princeps would now assume responsibility for their education and advancement in Roman society. Seen as his successors, the young boys were wildly popular with the Roman People and expectations for them ran high.

The months passed peaceably until, in the late summer, reports reached Rome from the legatus Augusti pro praetore of a military disaster in Belgica. The incumbent governor, having assumed the province from Agrippa in late 19/early

18 BCE, was M. Lollius. This high-performer in the league of provincial governors had stumbled – badly.22 An alliance of Germanic tribes on the right bank of the Rhine had crossed the river and raided his province. Florus writes:

The Cherusci, Suebi and Sugambri had begun hostilities after crucifying twenty of our centurions, an act which served as an oath binding them together, and with such confidence of victory that they made an agreement in anticipation of dividing up the spoils.23

Of them, ‘it was the Sugambri, who live near the Rhenus, that began the war’ under the leadership of their chief Maelo.24 As well as booty, the Sugambri – who, in Iulius Caesar’s day, had united with the Suebi, Tencteri and Usipetes – were looking for a new homeland.25 The new alliance crossed the Rhine on boats and rafts and advanced deep into Belgica. It ambushed a unit of Roman cavalry, which was out on a routine exercise.26 Chasing down the Roman fugitives, the Germanic warriors then collided with Lollius riding at the head of his legion coming the other way. In the ensuing battle, the men of Legio V Alaudae witnessed their prized aquila standard stolen away.27 Having only three years before recovered the signa lost during Rome’s historic defeats in Parthia, it was an acute embarrassment to Augustus to see an eagle lost by one of his own handpicked legates operating under his auspices. Incensed by the inexcusable failure, he prepared to visit the province in person. There would have to be consequences.

| L. Domitius Cn. f. Ahenobarbus | P. Cornelius P. f. Scipio | |

| suff. | L. Tarius Rufus |

In the spring, leaving Statilius Taurus as praetor urbanus in charge of affairs in Rome, Augustus travelled north to Gallia Comata with Tiberius by his side.28 The greatest of the wars which at that time fell to the lot of the Romans,’ writes Dio, ‘and the one presumably which drew Augustus away from the city, was that against the Germans.’29 What many were beginning to call the Clades Lolliana, (the ‘Disaster of Lollius’) was to Augustus’ knowledge still unresolved.30 When he reached Colonia Copia Felix Munatia, he learned the full facts from the legate himself:

He found no warfare to carry on; for the barbarians, learning that Lollius was making preparations and that the emperor was also taking the field, retired into their own territory and made peace, giving hostages.31

Among those preparations may have been the erection of a small military outpost on the Rhine at Neuss, at the end of the Roman road from Copia Felix Munatia.32 The locations of the main legionary garrison in the region have still not been definitively identified, but the 16-hectare winter camp with its extensive outer system of ditches at Folleville in the Somme Valley in Belgica may date to this time.33 Reflecting that the event was more humiliating than serious, Augustus turned his attention instead to pursuits that did not require force of arms.34 He likely now began reorganizing the territories of Aquitania, Celtica and Belgica, which had largely remained unchanged since Iulius Caesar left them in 51 BCE, and among which the chiefs of the sixty or so nations frequently squabbled.35 Augustus reduced the territory encompassed by Gallia Comata, renaming it Lugdunensis (map 3), hiving off parts to the other two provinces and enlarging them in the process. The regional grouping would henceforth be referred to as Tres Galliae – or ‘The Three Gauls’ – but they would remain as Provinces of Caesar.

Lollius’ fate was also decided. He had been in the role of governor for almost two years. While one source describes him as a model of reliability and a man immune to greed, another portrays him quite differently, as crafty and deceitful.36 Augustus determined that a new leader was needed to carry through his provincial reforms without the risk of further embarrassment. He relieved Lollius of his command and replaced him with his own stepson.37 Lollius would never again serve as a provincial governor, and from this moment on the man would harbour a deep grudge against Tiberius.

If calamity had been avoided on the northern frontier, it was more than offset by violent disturbances elsewhere.38 In Central Europe, the Alpine nations of the Camunni and Vennii raised their shields and spears against the Romans; they were quickly subdued by the intervention of P. Silius Nerva, who could draw on experience of fighting a war in mountainous terrain with M. Agrippa in northern Spain.39 Nothing is preserved in the extant accounts about the course of his successful campaign. In the Western Balkans, seeing an opportunity for gain, the nations of northern Illyricum, in concert with the Norici in the eastern Alps, overran the Roman settlements at Istria.40 Emboldened by his recent victory, Nerva and his legates engaged the Balkan warriors who, now faced with a superior opponent, put down their arms and came to terms again. Fighting without their alliance partners, the Norici suspended hostilities and quickly agreed a pact with the Romans too.41 Meanwhile, in neighbouring Macedonia the Dentheleti and the Scordisci roamed the land, leaving destruction in their wake, while in Thracia L. Caninius Gallus – who is not recorded as having fought a war before – assisted the Roman ally Roimetalkes in his struggle against the Sarmatae, and succeeded in driving them from his kingdom and back across the Danube River.42

Agrippa, meanwhile, was heading east to take up another assignment and had reached Athens by the onset of winter.43 En route he had stopped off at coloniae – Augusta Buthrotum (Butrint) in Epirus, Augusta Aroe Patrensis (Patras) founded for the veterans of Legiones X Fretensis and XII Fuliminata, and Laus Iulia Corinthiensis (Corinth) in the Peloponnese – to meet with city officials and veterans.44 The stalwart commander was now constantly suffering severe pain in his legs.45 He had been living with the condition for years but had kept his ailment secret from Augustus. The loyal commander, now 49 years old, did not want to distract his friend or give him cause to worry, but on his way to Asia Minor he discreetly visited shrines of gods associated with healing, hoping to reduce his discomfort or find a cure.

M. Livius L. f. Drusus Libo L. Calpurnius L. f. Piso (Pontifex)

In the West, Augustus toured the Iberian Peninsula, making a point to visit the coloniae where veterans of the recent war were settling down and creating new lives for themselves.46 As he had done in Tres Galliae, he reorganised the region, creating three new provinces out of the old two.47

Hispania Tarraconensis was fashioned out of Hispania Citerior, incorporating the newly conquered territories of the Astures and Cantabri.48 This became the permanent base of the Exercitus Hispanicus. In the homeland of the Astures, Legio VI Victrix was stationed at Legio (modern León); Legio X Gemina was billeted at Astorga, and IIII Macedonica at Herrera de Pisuerga (Palencia) among the Cantabri – all fortresses apparently being founded after the war at strategic locations to facilitate communications and troop movements.49 Atlantic-facing Lusitania, also a Province of Caesar, was delimited in the north by the Douro River and in the east side its border passed through Salmantica (Salamanca) and Caesarobriga (Talavera de la Reina) as far as the Anas (Guadiana) River.50 Its capital was the colonia Augusta Emerita (Mérida). Baetica, the third administrative entity, was to be a ‘Province of the People’ governed by a proconsul from its capital at Corduba (modern Córdoba).51 A new road, the Via Augusta, was constructed across the Iberian Peninsula to connect the Gallic border of Tarraconensis with the Pillars of Hercules at Gades; at the crossing of the Baetis River on the borderline of Baetica, a bridge with an arch was erected (the Ianus Augusti) bearing an inscription which marked the starting point for the distances on the milestones along the road.52

Native resistance having been broken, the Romans could begin full economic exploitation of the region. A reported 20,000 pounds of gold were extracted from mines each year, some of which would be used to pay the army.53 The farmers of Baetica would grow rich providing the Roman army with olive oil as far away as Germania.54 Many local men of military age chose to make careers for themselves in the Roman auxiliary army and followed the signa of the Alae Asturum and Cohortes Asturum et Callaecorum.55

In Gallia Cisalpina (the region of northern Italy beyond the Po River and south of the Alps), the native people – in particular the Raeti – were unwilling to accept the encroachment of Roman settlers who had made homes in numerous coloniae and municipia and constantly traipsed through their territory.56 Their response was to attack the travellers – behaviour that was to be expected of barbarians, notes Dio – but the cruelty of some acts allegedly committed by the Raeti shocked even the Romans. It was reported they slew not only all their male captives who were old enough to bear arms, ‘but also those who were still in the women’s wombs, the sex of whom they discovered by some means of divination’.57 Augustus now had his casus belli, if he needed one. The Romans had engaged the Raeti before: L. Munatius Plancus had fought them around 43 BCE, eliminating them as a threat to Gallia Narbonensis and Comata.58 This new war would be one of outright conquest.

Tiberius was already developing an acumen for military affairs. His younger brother was as yet untried. This was his opportunity to learn the arts of war. Augustus chose the 23-year old Nero Claudius Drusus (plate 26) to command the campaign in the Alps.59 Paterculus describes Drusus as:

A young man endowed with as many great qualities as men’s nature is capable of receiving or application developing. It would be hard to say whether his talents were better adapted to a military career or the duties of civil life.60

To succeed in the coming war, he would have to be a fast learner.

No doubt guided by Augustus and his older brother, Drusus assembled his expeditionary army. He began the campaign on the northeastern side of the Italian peninsula, moving from the Veneto to the foothills of the Dolomites (map 8).61 He engaged the Carni as well as certain tribes of the Norici, among them the Taurisci, and made safe the area around the city of Aquileia and its important port on the Adriatic Sea.62 Moving inland, he encountered the Breuni, Genauni and the Ucenni nations.63 It was ‘near the Tridentine mountains’, Dio writes, that Drusus clashed with a detachment of Raeti warriors ‘which came to meet him’.64 His men easily overwhelmed the lightly armed fighters.65

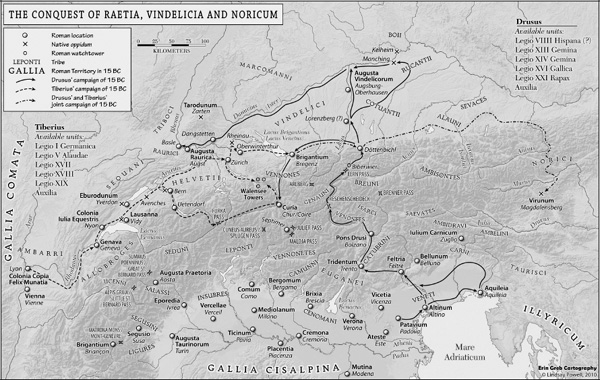

Map 8. Military operations in the Alps, 15 BCE.

Drusus’ army then marched north following the direction of the adjacent valley into the Alps. The course of the future Via Claudia Augusta suggests he chose the Reschen (or Reschen-Scheideck) Pass, which follows the course of the Adige (or Etsch) River.66 The ability to use river craft for at least part of the outbound journey may have swayed Drusus’ decision to take it over the alternative Brenner Pass.67 On the south side, the pass was wide, level and ideal for marching legionaries, their pack animals and waggons. Rising over the main chain of the Alps, the Reschen Pass connects the Inn River valley in the northwest with the Vinschgau valley in the southeast. Polybius describes this pass – as he does all the others traversing the Alps – as ‘excessively precipitous’.68 The young commander may have been the first to establish a permanent crossing over the Adige at Bolazano, known from Roman sources as Pons Drusi (‘Drusus’ Bridge’).69 From here the Reschen Pass formed a corridor of approximately 160 Roman miles (240 kilometres) from Pons Drusi to the foothills of the Schwäbisch-Bayerisches Alpenvorland along which to move his men and matériel.70

In contrast, the northern side of the pass formed a narrow and steep bottleneck, nowadays called the Finstermünzpaß (1,188 metres), which would slow down their advance. Roman troops faced a tough ascent crossing the streams in the valleys without the benefit of military roads and bridges. With the Romans in hot pursuit, the Raeti retreated up the pass. They resorted to ever more desperate measures. When they had used up their arsenals, records Florus, the women used their own children as weapons, smashing their heads against the ground and flinging their limp bodies at the approaching Romans.71 Drusus’ army systematically defeated them. Units of troops were stationed along the route of the Roman advance to relay communications back and forth.72 In just a few weeks, Drusus’ expeditionary force emerged victorious into the foothills of the Schwäbisch-Bayerisches Alpenvorland. Receiving the news that Drusus had defeated the Raeti and that they had been ‘repulsed from Italia’, Augustus rewarded him with a promotion to praetor – the magistracy ranked just below consul.73

The fleeing Raeti spread into neighbouring Gallia Lugdunensis. Augustus dispatched his elder stepson with an army and orders to quell the Alpine nations once and for all.74 Tiberius, likely following the course of the Rhône River (Rhodanus) or the Jura Mountains, succeeded in subjugating the Alpes Poeninae and all the access routes from the west. He may have split his troops and taken the Rhine route via Walensee, or additionally the Valais over the Furka Pass.75 Meanwhile, Drusus’ men marched from their new positions along the River Lech to the source of the Rhine, or followed the Danube to its source.76 Dio writes that ‘both leaders then invaded Raetia at many points simultaneously, either in person or through their deputies’, inferring that the brothers were executing a pre-agreed, co-ordinated plan.77 They fought in pitched battles that saw heavy losses among their opponents, but few Roman casualties.78 When Tiberius reached a major lake, he took the shortest route, ordering his men to construct boats with which they launched an audacious amphibious operation to reach the other side, crossing the water and taking their opponent completely by surprise.79 Even the boldest of the Raeti nations, the Cotuantii and Rucantii, could not muster the forces to repel the invader.80 Attacked on all sides, their resistance finally collapsed.81

Keen to ensure a lasting peace would follow, Tiberius and Drusus were determined to prevent the survivors from reuniting and fighting against them at a later time. As A. Terentius Varro Murena had done with the Salassi:

because the land had a large population of males and seemed likely to revolt, they deported most of the strongest men of military age, leaving behind only enough to give the country a population, but too few to begin a revolution.82

Many of the deportees would serve in the Roman army with new units of Cohortes Raetorum.83 Tiberius gave out decorations to legionaries who had demonstrated valour during the campaign.84

By the summer, the Claudius brothers had begun operations in the Alpenvorland, reaching as far north as the banks of the River Danube. Facing them now were the tough warriors of the Vindelici nations, Iron Age Celtic people who were particularly feared for their brutality and cruelty. The Clautenatii, Licatii and Vennones were reputed to be the boldest and bravest of them.85 Living in organized communities, many had settled in fortified cities or oppida.86 Roman troops were trained for siege warfare using a variety of techniques and technologies. By such means, Drusus’ men stormed ‘many towns and strongholds’ with ruthless efficiency.87 The date of the siege against the stronghold of the Genaunes is known.88 Their citadel is recorded as having fallen to Drusus on 1 August – an auspicious date as fifteen years earlier, on the same day, the then Imp. Caesar had taken Alexandria from Kleopatra.89 The resistance of the Vindelici ceased.90 Several Cohortes Vindelicorum came into service after this date. Tiberius distributed more awards for distinguished service to men of the legions.91

The Roman army continued its eastward march. In its sights was Noricum, a kingdom which had co-existed peacefully with the Romans since establishing formal relations in 186 BCE, but had upset the arrangement the year before when it had stirred up unprovoked trouble.92 Its principal city was Virunum, a formidable oppidum atop the Magdalensberg.93 Below it, on a south-facing terrace, was an entrepôt where Romans traded for resin, pitch, torches, wax, cheese and honey, as well as gold and high quality iron ingots called ferrum Noricum.94 The attack seems to have taken the Norici by surprise. Feared warriors in their own right, Florus writes that they had fooled themselves into thinking that their natural mountainous defences would be deterrent enough against the Romans, who ‘could not climb their rocks and snows’.95 They were wrong to think so. The gates of Virunum were breached and the kingdom of Noricum fell to the Romans. In a single summer campaign the brothers had subjugated the region.96 The requirement for payment of tribute annually was imposed on them as punishment for their audacity.97 Soon men of military age began serving with the Alae and Cohortes Noricorum.98

In his stepsons, Augustus had two young men he could promote as all-Roman heroes.99 New coins were struck showing the figure of Augustus in a toga seated on a curule chair upon a raised dais, his right arm reaching down to receive olive branches from the two armed figures of Drusus and Tiberius wearing military cloaks (plate 27).100 The legend ‘IMP X’ below attested to the acclamation by the troops of Augustus as imperator for a total of ten times. In his fourth Carmina, published two years later, Horace extolled:

What honours can a grateful Rome,

A grateful Senate, Augustus, give

To make thy worth through days to come

Emblazon’d on our records live,

Mightiest of chieftains whomsoe’er

The sun beholds from heaven on high?

They know thee now, thy strength in war,

Those unsubdued Vindelici.

Thine was the sword that Drusus drew,

When on the Breunian hordes he fell,

And storm’d the fierce Genaunian crew

E’en in their Alpine citadel,

And paid them back their debt twice told;

’Twas then the elder Nero came

To conflict, and in ruin roll’d

Stout Raetian kernes of giant frame.

O, ’twas a gallant sight to see

The shocks that beat upon the brave

Who chose to perish and be free!

As south winds scourge the rebel wave

When through rent clouds the Pleiads weep,

So keen his force to smite, and smite

The foe, or make his charger leap

Through the red furnace of the fight.101

The young Drusus, in particular, had demonstrated virtus in the best tradition of his ancestors:

So look’d the Raetian mountaineers

On Drusus: whence in every field

They learn’d through immemorial years

The Amazonian axe to wield,

I ask not now: not all of truth

We seekers find: enough to know

The wisdom of the princely youth

Has taught our erst victorious foe

What prowess dwells in boyish hearts

Rear’d in the shrine of a pure home,

What strength Augustus’ love imparts

To Nero’s seed, the hope of Rome.102

The brothers seemed invincible in the face even of the most brutal and savage of foes:

What will not Claudian hands achieve?

Iove’s favour is their guiding star,

And watchful potencies unweave

For them the tangled paths of war.103

Tiberius had proved his ability to get results once again. After just a year in the governor’s role, Augustus charged Tiberius with taking command of Illyricum, where the nations were restless.104 In the new year his younger brother would replace him as legatus Augusti pro praetore for Tres Galliae – a significant promotion for a man who barely a year before had no military experience at all.

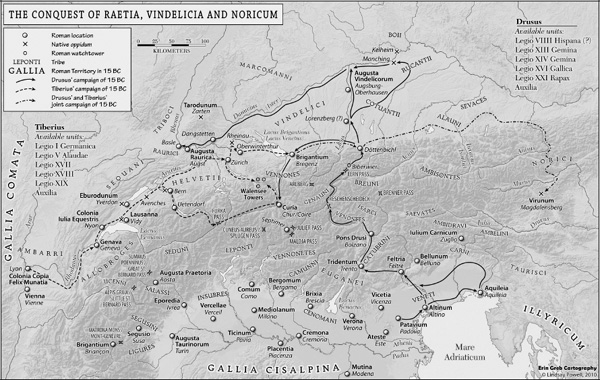

Operations were suspended in the region. Roman armies, or those of their allies, now controlled most of the main passes throughout the Alps.105 To ensure their gains were secure, the legions and auxilia would spend the winter in newly conquered Raetia and Vindelicia.106 The site of the camp located at the convergence of the Lech and Wertach rivers and on the Singold would become the civitas capital of the Vindelici and be given the official name Augusta Vindelicorum in honour of the princeps. Legio XIX, under the command of P. Quinctilius Varus, the former quaestor of Augustus, established a fortress further west at Döttenbichl in Oberammergau (fig. 6).107 An auxiliary fort may have been established at Strasbourg on the Rhine at the head of the Vosges Mountains to defend the interior of Gallia Lugdunensis.108

In North Africa there was military activity too. This year P. Sulpicius Quirinius had assumed his post as proconsul of Creta et Cyrenaica, one of the Provinces of the People.109 He is described by one Roman commentator as ‘an indefatigable soldier’.110 If he was looking for a war to wrap himself in glory, he found one. The Nasamones, a nomadic tribe of Berbers, provided the opportunity in Cyrenaica. No details of the conflict survive, only that he successfully subjugated them.111 In the Sahara Desert, Quirinius also battled the Marmaridae and Garamantes, previously beaten by Cornelius Balbus in 20 BCE. He ‘might have returned with the title of Marmaricus’, writes Florus, ‘had he not been too modest in estimating his victory’.112 Having proved himself ‘by his zealous services’, however, Quirinius had impressed his colleagues and would win a consulship.113 Valour and victory on the battlefield still counted in the race for political office.

Figure 6. Legio XIX, commanded by Legatus Legionis P. Quinctilius Varus, brought artillery on the campaign to complete the conquest of the Alps in 15 BCE. This catapult bolt, bearing the legion’s index number, was used in anger.

On his second mission in the orient, Agrippa finally arrived at Antiocheia. On his way he founded a new colonia at Alexandria Augusta Troadis (modern Eski Stambul in Turkey).114 Having reached Syria, he soon departed to the colony of veterans of Legiones V Macedonia and VIII Augusta at Iulia Augusta Felix Berytus (modern Beirut) to meet with officials.115

M. Licinius M. f. Crassus Frugi Cn. Cornelius Cn. f. Lentulus (Augur)

While Augustus was busy in the West, his associate Agrippa was on a state visit to Iudaea, enjoying the hospitality of King Herodes. The two statesmen were becoming firm friends. During the return sailing to Lesbos, Agrippa was made aware of the deteriorating political situation in the kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus on the northern shores of the Euxine (Black) Sea.116 Immediately following the death by suicide of King Asander, a man named Scribonius, claiming to be the son of Mithradates VI of Pontus, had assumed the throne and declared that he had received the kingdom legitimately from Augustus.117 Agrippa refused to accept this version of events and determined that direct intervention was needed. He sent instructions to Polemon, the king of Pontus and the Roman ally closest to the trouble spot, to move quickly to expel Scribonius. Furious at the pretender’s audacity the people of the kingdom had, meanwhile, assassinated him. The crisis was already over when Polemon berthed his ships at the dock at Tanaïs. Polemon’s arrival now led to anxiety that he would lay claim to the kingdom himself, and the local people resisted his involvement in what they considered an internal matter.118 That fear was realized when fighting ensued and Polemon sacked the city; yet unbowed, the people continued their resistance.119

Having reached Mytilene in the spring, Agrippa departed for the Bosporus with a fleet of ships to personally take charge of operations. Before he left, he wrote to Herodes with a request for ships, crews and troops. The king of Iudaea responded without hesitation, but when his fleet, delayed by winds at Chios, reached Lesbos he discovered the Roman commander’s ships had already left for the Cimmerian Bosporus.120 Herodes finally caught up with Agrippa at Sinope in Pontus (Sinop on Cape Ince, Turkey).121 Agrippa was delighted by the king’s arrival.

In the Cimmerian Bosporus, Polemon was struggling to contain the problem he had largely created himself. He fought the rebels in a battle but they would not submit to him.122 Only when Agrippa came to Sinope with the purpose of conducting a campaign against them and news of his imminent arrival in the Bosporus reached the rebels did they finally lay down their arms and surrender to Polemon.123 Dio’s account infers that Agrippa’s formidable reputation alone was enough to break the resistance and that he did not need to make the journey across the Black Sea. Orosius, however, clearly states that he was actually involved in fighting, writing: ‘Agrippa, however, overcame the Bosporani and, after recovering in battle the Roman signa formerly carried off under Mithridates, forced the defeated enemy to surrender.’124 The outcome was that Agrippa brokered a new settlement between the warring factions. Dynamis (the widow, first of Asander and later Scribonius) was to become Polemon’s wife; and the Cimmerian Bosporus was re-affirmed as a client kingdom of the Roman Empire, required to provide men to serve in the Roman army.125 Augustus approved. 126 Agrippa also bound neighbouring Cheronesos (now Crimea) to the Cimmerian Bosporus, thereby securing control over the entire peninsula for Rome.127

Just as he had done after the Bellum Cantabricum et Asturiucum five years previously, Agrippa sent his official after-action report not to the Senate, but directly to Augustus. The ramifications of his decision were far-reaching. ‘In consequence,’ writes Dio, ‘subsequent conquerors, treating his course as a precedent, also gave up the practice of sending reports to the public.’128 Nevertheless, for his successes the Senate still voted Agrippa a triumph – and, as before, he declined it, though the sacrifices offered to him did take place. That decision was consequential too. ‘For this reason – at least, such is my opinion,’ remarks Dio, ‘no one else of his peers was permitted to do so any longer either, but they enjoyed merely the distinction of triumphal honours.’129

Tiberius returned to Rome while the legions under his command marched out of the foothills of the Alps to the western Balkans. M. Vinicius had recently assumed from him his post of legatus Augusti pro praetore of Illyricum.130 The units would reinforce the four legions already in the region, where the Breuci and Dalmatae had taken up arms.131 ‘Caesar [Augustus] sent Vinnius to subdue them,’ writes Florus (who calls the conflict the Bellum Pannonicum), ‘and they were defeated on both rivers.’132

As the new governor of Tres Galliae, one of Nero Drusus’ first tasks was to undertake a census of the population.133 To bind them closer to Rome, and thus neutralize them as a threat to internal security, he established a council of the sixty Gallic nations called the Concilium Galliarum.134 This consultative body would meet annually at Colonia Copia Felix Munatia, at a new complex to be the focus of the cult of Roma and Augustus, the foundations of which were laid this year. In addition to the normal duties of a propraetorian legate, he was given care of the mint which had been set up in the city. It met the ongoing need for production of silver denarii to pay the soldiers of the legions stationed in the West. The facility came with its own high-security detail, a unit of the Cohortes Urbanae, complete with an officer holding a key to the prison.135

Augustus had appointed his stepson expressly to prosecute his war of conquest of Germania.136 The commander-in-chief’s intent is summed up by Florus:

Since he was well aware that his father, Caius Caesar, had twice crossed the Rhenus by bridging it and sought war against Germania, he had conceived the desire of making it into a province to do him honour.137

The preparations would be extensive and cover a wide front; the planning would be thorough and take up to two years to complete. The theatre of operations was to be a vast tract of land from the Rhine to the Weser or Elbe rivers, encompassing many kinds of terrain and an unknown number of tribes and nations between them. As he had done in the Bellum Cantabricum et Astricum, Augustus would bring to bear overwhelming force upon the enemy. With the Astures and Cantabri finally quelled, there was an opportunity to dilute the heavy concentration of military assets in the Iberian Peninsula. Several of the eight legions stationed in Hispania Tarraconensis could now be drawn down and redeployed where they were needed in Illyricum and Tres Galliae. Legiones XIV Gemina and XVI Gallica marched to join I, V Alaudae, XVII, XIIX and XIX already stationed in Tres Galliae.138

The immediate task was to move them to new locations along the Rhine. The siting of the military camps makes it is clear the invasion plan was well conceived. From the outset, Drusus intended to dominate the river by controlling all lines of communication along it.139 According to Florus, he established over fifty military bases (castella) on the river, though modern archaeology has yet to find all of them.140 He mentions bridges (pontes) being constructed at Borma or Bonna (perhaps Bonn) and Gesoriacum (identified with uncertainty as Boulogne) and that Drusus ‘left fleets (classes) to protect them’.141 At key strategic points along the lower and middle Rhine, five new legionary fortresses were built at Batavodurum (Nijmegen-Hunerberg), Vetera (Xanten), Novaesium (Neuss), Oppidum Ubiorum (Cologne) and Mogontiacum (Mainz).142 To facilitate the movement of men and matériel, a military road connected the bases with the provincial command at Colonia Copia Felix Munatia.143 Smaller forts for auxiliary units and supply dumps were constructed along this road at Andernach, Argentorate (Strasbourg), Asciburgium (Asberg), Bingen, Bonna, apud Confluentes (Koblenz), Speyer and Urmitz.144

Mogontiacum, built on a 40-metre high rise above the river, was the most southerly fortress of the new Rhine offensive line.145 Two legions, possibly XIV Gemina and XVI Gallica, shared this basecamp. It controlled a network of suppliers whose commodities were essential to the war effort. At Weisenau, about 3.5 kilometres (2 miles) south of Mogontiacum, another military installation has been identified on an escarpment overlooking the Rhine River.146 About 2 kilometres (1 mile) downstream at Dimesser Ort was a harbour.147

Some 200 kilometres further down river from Mogontiacum stood Oppidum Ubiorum. It was the burgeoning market town of the Ubii nation, founded when Agrippa granted them sanctuary on the Roman side of the Rhine in 39/38BCE or 20/19BCE.148 The Roman army had bases here at different times over several years, but which were probably located away from the civilian settlement. The new installation may have been the new winter camp of Legio XIX, which was earlier based at Dangstetten, and possibly shared it with Legio XVII.149

Located about 50 kilometres northwest of Oppidum Ubiorum, the original outpost of Novaesium (called ‘Neuss A’ by modern archaeologists) was now redeveloped into a full-size winter camp (or ‘Neuss B’).150 Polygonal in shape with a V-profile ditch, it enclosed an area of at least 27 hectares, large enough for one legion. 151 It may have been home to Legio XVII or XVIII.152 A wooden bridge was constructed to carry the military road uninterrupted over the marshy Meertal to the northwest.153

Laying 65 kilometres down river on the Fürstenberg was Vetera (meaning ‘the Old One’).154 It was located opposite the Lippe River (Lupia). Traces of ditches and earthen rampart indicate it may have been large enough to house two legions, the most likely candidates being V Alaudae and XVIII.155

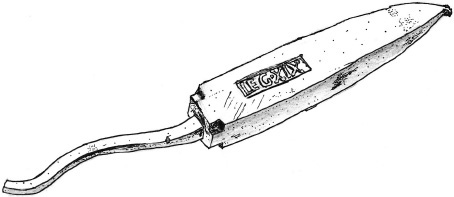

The penultimate fort in the chain of military bases was Batavodurum. Located 2 kilometres east of modern Nijmegen at a place called Hunerberg, the legionary camp occupied an escarpment above the floodplain of the Waal River (Vahalis).156 At 42 hectares, it was large enough for two legions (map 9). It may have been the winter camp for Legiones I Germanica and V Alaudae.157 Unusually, the fortress lay outside the Roman Empire in the territorium of the Batavi, whose permission must have been sought before construction work could begin.158 These native warriors would be part of Drusus’ expeditionary force. Honoured allies to the Romans, they were fine horsemen known for their ability to cross rivers in full armour.159 It was widely believed that, like the best weapons, they were only to be used in times of war.160 The exquisite quality of the armour and equipment found at the site emphasizes the high value the Romans placed on their Batavian allies. Several Alae Batavorum and at least nine Cohortes Batavorum are recorded.161

Map 9. Plan of Nijmegen-Hunerberg Roman Fort, The Netherlands.

The locations of the military installations suggest the region had been wellsurveyed by the Romans in advance of the campaign and that they were intended to be the embarkation points for invasion routes into Germania.162 From Batavodurum, the army could approach from the west, moving northeast towards the Ems River (Amisia) and then to the Weser River (Visurgis). From its bases further along the Rhine, the army could follow its tributaries, reaching, first, the Weser River and then the Elbe River. From Vetera, the army could thrust into Germania following the course of the Lippe. From Novaesium, there was potential for a direct line of attack up the Ruhr River (Rura). From Oppidum Ubiorum, Roman forces could go north to the Ruhr or march south to the Sieg. From Mogontiacum, the army could move along the Main River (Moenus) and then march across to the Saal River (Sala), a tributary of the Elbe.

An amphibious landing to deliver Roman troops into Germania using its rivers from the north must have been part of the original strategic concept for the campaign right from the start. The North Sea (Mare Germanicum) was treacherous and dangerous to a flotilla of small ships carrying men and matériel sailing out via the mouths of the Rhine or Waal rivers. The audacious option chosen required one or more canals to be excavated between the River Rhine and the large inland sea called Lacus Flevo (formerly the Zuider Zee, nowadays the Ijsselmeer) to allow a fleet to sail into the relatively protected and calmer Wadden Sea, and thence reach the estuary of the Ems. The ‘Drusus Canal’ (fossa Drusiana) system was, by Suetonius’ account, located beyond the Rhenus and took ‘immense exertion’ to build.163 It comprised an agger (a word translated variously as ‘embankment’ or ‘rampart’) and other associated structures referred to as moles (‘dams’ or ‘dykes’).164 Nearby was the last fort in the chain, Fectio (Vechten), which is known from inscriptions to have been a naval base.165 Work also began on a fleet of hundreds of ships and barges that would ferry the troops and matériel across the sea and directly into the war zone.

One last corner of the southwestern Alps held out against Rome. No details of the campaign or who led it survives – though Drusus would seem the likely candidate. Dio writes only that in ‘the Alpes Maritimae, inhabited by the Ligures who were called Comati, and were still free even then, were reduced to slavery’.166 The courage of these mountain warriors was channelled into new Cohortes Ligurum, which entered service soon thereafter.167

Just as the great project to annex Germania was about to begin, Augustus’ legal power to do so was due to end. The five-year extension to his imperium granted in 18 BCE would expire at the end of December. To complete the task he would need the Senate to ratify another lustrum.