Sources: Dio; Florus; Josephus; Livy; Orosius; Tacitus; Velleius Paterculus.

In the beginning there was war. To the Romans it was the prerequisite for peace. Augustus was clear about what pax meant to him: ‘peace, secured by victory’.1 The Latin word pax derives from the verb pacere, meaning ‘to pacify’ or ‘to subdue’. After a struggle, one party must stand tall, the other must submit. The derivative pactio means a bargain or agreement or contract. The defeated must keep their word. Winning wars required mastery of many skills. To achieve victory, and so accomplish a sustainable peace, Augustus had to be effective both as a military leader and as a manager of war.

Augustus as Military Leader

Modern historians have struggled to describe the kind of leader Imp. Caesar Divi filius Augustus was. They have variously called him an ‘autocrat’, ‘between citizen and king’, a ‘monarch’, a ‘military dictator’, ‘Rome’s first emperor’, even a ‘warlord’, and his form of rule a ‘military regime’ or a ‘monarchy’.2 None of these titles adequately encompasses his unique leadership position in Roman society and arguably even obscures it because each comes with its own baggage acquired from use over the subsequent centuries. Augustus was not an elected magistratus and he did not hold the official title of the ‘proconsul of the imperium of the Roman People’.3 Augustus referred to himself as imperator, the explicitly military title meaning ‘commander’ – adopting it as his praenomen as early as 38 BCE – and also as princeps, a reference to his primary position in the Senate and Roman society.4 Contemporaries often called him a dux, ‘leader’.5 His rise to power was based on victories over his opponents and his enduring rule depended on command of the army. The Roman Commonwealth had always been a compromise between a democracy and a paramilitary regime, its elected magistrates holding term-limited imperium, its consuls empowered to lead its citizen militia to battle, its electorate even willing to allow a temporarily appointed dictator to govern the nation during an existential crisis. Thus, ‘commander-in-chief’ or ‘single dominant military leader’ would seem to come closest to accurately describing Augustus’ place in Roman society.6

There was no military academy for officers in Rome. The Romans believed that leadership could not be taught, but could only be learned. Augustus, like all his peers, would have learned the arts of generalship and war from reading, observing and, above all, by doing it. Ancient historians certainly recognized good military leadership when they saw it. The Greek and Roman works of history are filled with exemplars, from Leonidas of Sparta to Claudius Marcellus.7 These men displayed courage or manliness (virtus) in abundance. Virtus was ‘nearly the most important thing in every state, but especially in Rome’, writes Polybius, observing the rise of the Romans as a military power in the Mediterranean in the second-century BCE and attempting to explain it to a Greek audience.8 There were digests – didactic compilations – in which their authors quoted examples of generalship and military strategy from history; and there were handbooks on military science, drill and tactical aspects of combat such as fighting formations, deceptions and siege warfare.9 Augustus could have also studied the memoirs of great Roman commanders, such as Sulla and Marius, or their and others’ war reports.10

Most remarkably, in his youth Augustus had access to arguably the ancient world’s greatest practitioner of military science, C. Iulius Caesar. The older commander had seen potential in his great nephew and encouraged him as he grew up to take an active role in the army. We can only guess at the kinds of conversations and exchanges these two men had, and how much his young relative learned from the genius of military leadership, strategy and tactics. After Caesar’s death, the teenage heir did not lack for advisors. He had access to men who had known Caesar well, such as L. Cornelius Balbus, C. Oppius and for a time the dictator’s erstwhile right-hand man, M. Antonius. Later, among his own peers, Augustus could draw on the abundant talents of his friends M. Agrippa and Statilius Taurus. But Augustus was no ‘armchair general’. To this learned knowledge he could add personal experience and the judgment that it afforded. He had already demonstrated years after 44 BCE the innate leadership attributes of character, intellect and presence in different measures.11 Expressed in modern terms, he showed warrior ethos, confidence, military bearing, resilience, mental agility and other qualities marking him out as an effective leader of some merit, despite his political enemies’ attempts to belittle his talents. He even had real scars to prove he had been in battle. Augustus was, in every way, a military leader. People followed him. He never gave up. Yet he was also aware he had shortcomings.

Then as now, being a military leader did not mean always having to lead troops on the front line. Leadership is a broader concept. In the absence of a definition of leadership in the military and its attributes from an ancient writer, we must look to a modern authority. The Army of the United States defines leadership as ‘influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation, while operating to accomplish the mission and improve the organization’.12 As the leader, Augustus could only succeed through the appeal of his vision and by inspiring and motivating those around him that the ‘whats’ and ‘whys’ were important enough to commit to.

The sources of Augustus’ influence were emotional, legal and religious. He had inherited from Iulius Caesar a powerful name. ‘Caesar’ evoked strong emotions: admiration and loyalty in some, fear and loathing in others. It was further enhanced after the dictator’s deification by the bond he styled as Divi filius, which he included in his amended name.13 (It was hard to argue with the ‘son of god’.) Through his adoption into gens Iulia, he could trace his ancestry back through time along a direct line to Iulus (Ascanius), Aeneas and to Venus.14 Over the 40s and 30s BCE, through his own deeds – by successfully confronting the assassins, then overcoming those who stood against the Triumvirate and ultimately his rivals in it too – he built up immense auctoritas. It had connotations of auctor, a leader able to wield influence though the qualities of his intellect or military force.15 The agreement with the Senate in 28 and 27 BCE granted him his legal military power – renewed and extended in 23 BCE as imperium proconsulare maius – to command in his province. After 19 BCE, the summum imperium auspiciumque formally established him as the supreme commander over all others of nominally equal rank anywhere. The honorary title Augustus, meaning ‘revered one’ and implying he was worthy of veneration, only added to his already substantial aura.

Even before he received his title Augustus, Imp. Caesar cleverly – it might be said cunningly – tapped into the Romans’ profound reverence for tradition (mos maiorum) and piety (pietas) to sanctify the beginning and ending of his wars. Supplementing the long-honoured rites, he reintroduced other long-abandoned rituals. Thus, to validate his action against Antonius and Kleopatra, in 31 BCE he reinstated the ancient ceremony undertaken by a fetial priest, who struck an irontipped spear in the ground of the Temple of Bellona while intoning the declaration of war. Having defeated them, in 29 BCE, he restored the augurium salutis, a ceremony which publicly affirmed that the nation was no longer at war or preparing for one. The last time it had been done was in 63 BCE – co-incidentally the year of Augustus’ birth. Also in 29 BCE, he closed the doors of the Temple of Ianus Quirinus. They had last been shut in 235 BCE to celebrate the end of the First Punic War. Augustus would often look to the past to find a solution to a modern problem.

Augustus provided purpose and long-range direction. After the murder of Iulius Caesar in 44 BCE, his 19-year-old legal heir sought justice for the crime. He was explicit about that goal very early in his quest and applied himself with a stubborn singularity of mind to achieving it. To invoke a divine sponsor for his enterprise, he created an avatar of the Roman god of war, calling him Marti Ultori, ‘Mars the Avenger’. Not having all the military resources to complete the task alone, Imp. Caesar joined with M. Antonius and Aemilius Lepidus in a Commission to Restore the Commonwealth from the men who they claimed had hijacked it and rained destruction upon it. Soon after the assassins had been killed at Philippi in 42 BCE, frictions emerged between the members of the Triumvirate, which led inevitably to civil war.16 Caesar unceremoniously relieved Lepidus of his command. Antonius, despite his strange behaviour, was still popular with large segments of the Roman People and Senate. In 31 BCE, under the guise of a foreign war, Imp. Caesar set as his new goal to eliminate the Egyptian queen, the patron funding her Roman consort. He portrayed her as a threat to the integrity of the imperium of the Roman People, her lover as a victim of her guile. When Antonius did not leave her, he became a legitimate target. Caesar required all Italy to swear an oath to him before he went to war. Victory for him at this phase in his career was to remove Antonius and Kleopatra permanently.17 At Actium on 2 September, his opponent fled and a year later he was dead by his own hand – and the queen too.

Imp. Caesar was now the undisputed leader of the Res Publica, with an immense army under his command to impose his will.18 Remarkably, he did not march on Rome and impose a junta. It is not clear what he had envisaged beyond that point. In his Res Gestae, the victor states simply, ‘when I had extinguished the flames of the Civil War, after receiving by universal consent the absolute control of affairs, I transferred the Commonwealth from my own control to the will of the Senate and the Roman People’.19 He had avenged his adoptive father and he restored the Res Publica to its rightful masters. But was that really all he ever intended to do?

Initially, it seems, he was not interested in ruling over the entire Roman Empire. Such an ambition would not have been consistent with his professed commitment to a Res Publica restituta. Through the years 28 and 27 BCE, Imp. Caesar worked with the Senate to decide who controlled which regions of the Roman world and who commanded the army units within them. It was a political negotiation. His carefully stage-managed resignation in 27 BCE permitted an agreement – a pact – to be reached between the two parties. It granted him, now hailed as Augustus, for a period of ten years a provincia (meaning both territory and a duty).20 The presence of the army was required there because the province covered regions not yet pacified, or the nations adjacent to them had not yet subjugated, or the lands themselves were deemed difficult to cultivate, or a combination of these problems. Conveniently, there was a precedent. In the Lex Gabinia of 67 BCE, the Senate had granted Pompeius Magnus a provincia for three years to defeat the pirates operating at will in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. This extended term saved him the need to return to the Senate each year to renew his power.21 It was the vast size of Augustus’ province, combined with the decade-long duration of his imperium, that made his situation so novel and unprecedented.

In his provincia (comprising Hispania Citerior, Aquitania, Gallia Comata, Belgica, Narbonensis, Coele-Syria, Syria, Cilicia, Cyprus and newly acquired Aegyptus), Augustus had free rein to conduct affairs as he saw fit. It was a military matter. This arrangement also presented him with an opportunity. So long as there remained unsubdued peoples and unpacified regions, a military guard would be required – and a leader to command it. Waging war would become a central policy tool to ensure Augustus remained Rome’s commander-in-chief. Thus in his account of his deeds Augustus writes, ‘wars, both civil and foreign, I undertook throughout the world, on sea and land’.22 He knew well that every victory brought glory (gloria) and honour (decus) to the Roman People, which augmented his personal prestige (auctoritas) and worthiness (dignitas) in Roman society – just as had been the case with all successful commanders in the heyday of the Res Publica, from Cornelius Scipio Africanus to Iulius Caesar.

The question inevitably arises as to whether Augustus, as leader, had an explicit grand strategy. The term is defined as an overarching collection of policies, plans and directives that encapsulate the state’s conscious effort to mobilize the diplomatic, economic, military and political resources to advance and achieve its national interest.23 It is difficult to answer definitively because of the opaqueness of the decision-making process at the time and the type and quality of the records still available to us today. Writing two centuries after Augustus’ death, even Dio himself recognized the challenge of understanding how decisions were made:

Formerly, as we know, all matters were reported to the Senate and to the People, even if they happened at a distance; hence all learned of them and many recorded them, and consequently the truth regarding them, no matter to what extent fear or favour, friendship or enmity, coloured the reports of certain writers, was always to a certain extent to be found in the works of the other writers who wrote of the same events and in the public records. But after this time most things that happened began to be kept secret and concealed, and even though some things are perchance made public, they are distrusted just because they can not be verified; for it is suspected that everything is said and done with reference to the wishes of the men in power at the time and of their associates. As a result, much that never occurs is noised abroad, and much that happens beyond a doubt is unknown, and in the case of nearly every event a version gains currency that is different from the way it really happened. Furthermore, the very magnitude of the empire and the multitude of things that occur render accuracy in regard to them most difficult.24

However, there is a ‘paper trail’ of inscriptions, coins, letters, legal sources and Augustus’ own Res Gestae which expresses, justifies or celebrates imperial actions, even if the component parts were produced many years after the original policy decisions were taken; to which can be added archaeological evidence, which can indicate troop movements, type of units deployed and duration of stay.25 Indeed these underpin the research of the preceding chapters. From such sources the diplomatic and military policies can, within limits, be inferred, implied or extrapolated.

Modern scholars have long debated whether the Romans at any time had a long-term military strategy. They certainly understood the concept of ‘a plan of the whole war’.26 Based on their actions prior to the first-century BCE, however, it seems unlikely that they had one for building a transcontinental empire. The Roman People largely acquired their overseas dominions by accident and opportunism rather than through any grand design for world conquest. Roman citizens engaged in foreign wars primarily to defend their territorial acquisitions – the first war with Mithridates being something of an aberration.27 Rarely too did the legions fight to prevent an existential strategic threat – the three wars against Carthage being the notable exceptions.28 Yet fighting was in the Romans’ blood, a trait of their national character. Almost every year from 219–70 BCE the men of the Commonwealth marched off to war in their centuries and maniples, led by their praetors or consuls citing some justification or other for doing so.29 In the century Augustus grew up in, however, it was individuals with private armies seeking glory, prestige and booty for themselves – men such as Licinius Crassus, Pompeius Magnus and Iulius Caesar – who promoted the agenda for war.30

The opening line of the monumental inscription, written by Augustus in his seventy-sixth year of life and displayed outside his mausoleum, declares ‘the deeds of Divus Augustus, by which he placed the whole world under the sovereignty of the Roman People’.31 This statement refers to the world subject to Roman rule in 14 CE, the product of a restless ambition tempered by a lifetime’s lessons in the pragmatics of diplomacy and war. Harder to gauge is how Augustus saw the world after his victories at Actium and Alexandria, and how this informed his military strategy for the coming decades. It has long been hotly debated by modern historians.32 Several have argued that the frontiers of the Roman Empire evolved without any planning and that there was no strategic thinking behind where they lay.33 Some have interpreted the evidence to understand his approach either as evolving over time and not shaped by a unifying global strategic vision, or as a series of responses regulated by cautious pragmatism to events as they arose.34 These interpretations present Augustus as a more passive actor than the evidence from his deeds suggests he actually was. Augustus was most definitely not a pacifist.35

In his ground-breaking – but controversial – study, Edward Luttwak, a writer on strategic defence, attempted to synthesize military actions under Augustus into a cogent theory.36 He portrayed Augustus as a vigorous, proactive commander-in-chief unleashing wars of conquest in pursuit of establishing a defensible, ‘scientific’ frontier supported by an economy of force.37 Annexing the viable states of allies was not part of Augustus’ grand design; it was unnecessary because, in awe of their Roman patron, these allies were kept in virtual subjection.38 The army formed a protective circle around Rome, but was concentrated in multi-legion groups, uncommitted to the defence of any particular region, that could be assembled en masse to conduct campaigns, then drawn down and redeployed elsewhere. The benefit of such a flexible, mobile approach, Luttwak argued, is that troops could be moved without risking the security of the whole empire.39 The model goes a long way to explaining Augustus’ grand design, though it is still problematic.

The issue of borders is complex and discussion in the literature often centres around whether they were marked, fixed and defended frontiers where the army patrolled and collected customs duties.40 The eminent Sir Ronald Syme saw Augustus’ interest in conquering Germania as driven by the need to set a northern frontier to the empire along the Elbe and Danube Rivers, a hypothesis soundly disputed by Colin Wells, who had reviewed the available archaeological evidence.41 One historian has pointed out that the Roman Empire did not have borders in the modern sense but, in fact, existed within fuzzy intermediate ‘frontier zones’ that were neither fixed nor uniform.42 Yet Augustus did perceive frontiers of some kind. In 14 CE he wrote, ‘I extended the boundaries (finitima) of all the provinces, which were bordered (fines) by races not yet subject to our imperium.’43 If there is a single word that encapsulates that goal that shaped his policy and to which he devoted resources it is enlargement.44 As the poet Vergil’s Jupiter succinctly instructed Aeneas, Romans were not to be limited by the constraint of a border, but to wield power without end – imperium sine fine. Augustus was able to claim a direct connection with Aeneas.45 From the historical survey in the preceding chapters, it is clear that military actions were purposely launched by Augustus to push out the frontiers of his provincia – in Hispania Citerior, Arabia, the Alps and Germania – and where he could not, he enforced the existing ones, such as when his treaty partner Parthia attempted to bring Armenia into its sphere of influence.46 At the same time his legati were empowered – often working in tandem with allies and other legati – to deal with brigandage, foreign invasion and revolt in accordance with their duty of ensuring provincial security. All of these military actions aligned with Augustus’ ongoing political aim. Within the bounds of each of the ten-year periods (decennia) that his imperium was legally in force, he and his subordinates were engaged in both defensive and offensive operations. These might be completed before the ten-year term ended, or if not – as, in fact, happened – the case would be made to the Senate to renew his imperium to pursue them in the next.47

In his first decennium of holding basic military power (27–19 BCE), Augustus’ actions indicate a strategy aimed at removing immediate threats on the borders in the West and the East (table 5). There was interest in taking Britannia, but Augustus may have considered the island already part of the empire through treaties and friendship with British kings who had come to Rome in person and sought supplication from him. Augustus chose as his first military mission to finish the subjugation of the Iberian Peninsula, a project begun some 200 years before. He may have considered it an easy victory if overwhelming force was brought to bear. He laid out a plan to win, assembled a large army, chose the field commanders and coordinated manoeuvres with them. After leading the first thrust himself – cut short by sickness – a series of subsequent campaigns concluded by M. Agrippa finally broke the resistance of the two last Ibero-Celtic nations of Astures and Cantabri. In the East, Augustus personally ordered praefectus Aegypti Aelius Gallus to invade Arabia Felix in an attempt to annex it for its access to the lucrative trade routes with the Middle East and India. It failed spectacularly, though Augustus still saw value in claiming credit for it. Augustus’ major policy success of this period was to receive back from Parthia the signa lost by Crassus at Carrhae, achieving through diplomacy what M. Antonius had failed twice to do with armed force. Of the fifteen documented conflicts during this period, four were to quell revolts in conquered territories and four were responses to invasions into Roman-occupied space by foreign tribes. His legati led actions to address specific threats in Africa, the Alps and Aquitania. On account of victories in the field, Augustus could demonstrate he was making progress in pacifying his provincia – and as proof returned to the Senate the management of Cyprus and Gallia Narbonnensis – but more time was needed to complete the project and he gained restless Illyricum. By 19 BCE, he had consolidated his military and political primacy over the consuls and all other magistrates in the Res Publica.

The following year, the Senate renewed his imperium. The actions of the first half of his second decennium (18–14 BCE) indicate a continued commitment to conquest beyond the border of his province. If gaining more land in North Africa was of little value and the eastern border was claimed by Parthia, the open terrain on the right bank of the Rhine River now represented the best option for expansion. The trigger for action may have been the humiliation of Lollius in Tres Galliae by Germanic raiders in 17 BCE. Troops were drawn down from the Iberian Peninsula and transferred to Tres Galliae. Two years later, Augustus appointed a new generation of commanders – his own stepsons – to lead foreign wars to complete the annexation of the Alps, resulting in the subjugation of the Raeti, Vindelici and Norici. On the Rhine, massive investments were made in installations for legions and auxiliaries in preparation for a full-blooded invasion of Germania led by Nero Claudius Drusus. The German War was finally launched in the last half of Augustus’ second decade of imperium (13–9 BCE). A well-planned and executed campaign moved men and matériel from the northwest coast of Europe through Germania each season, first to the Ems, then to the Weser and finally to the Elbe River. Meanwhile, bandits, rebels and foreign invaders kept the Roman army and forces of its allies busy in Africa, Cilicia, Cimmerian Bosporus, Galatia, Illyricum, Macedonia and Thracia. As further evidence of progress with the project of pacification, the new province of Baetica, split off from Hispania Ulterior, was given to the Senate. Tragically, by the end of this period death had claimed the lives of both the greatest commander of his day, M. Agrippa, and the promising new military talent, Nero Drusus.

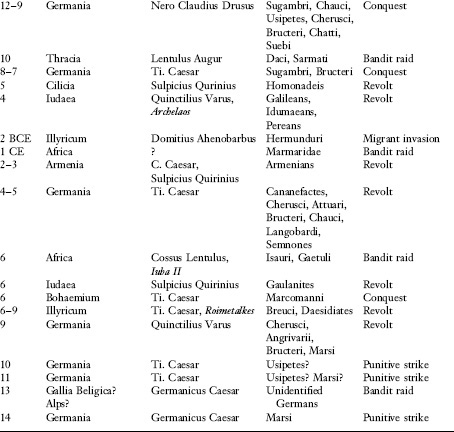

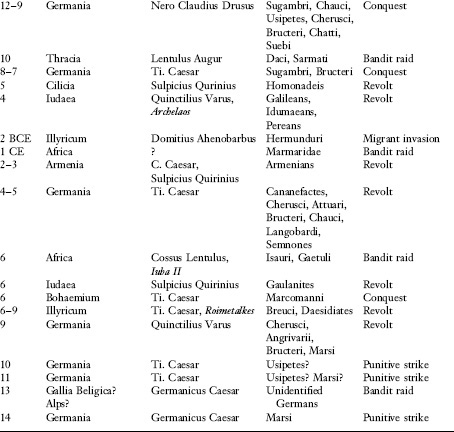

Table 5. Wars of Augustus, 31 BCE–14 CE.

Sources: Dio; Florus; Josephus; Livy; Orosius; Tacitus; Velleius Paterculus.

In his third decennium (8 BCE–2 CE), Augustus would look to Tiberius to take the lead in military matters. Germania was the priority. Tiberius picked up the campaign where his brother had left it and focused on the process of pacification by initiating civil settlement construction and road building, which continued over the next decade. The Sugambri, the cause of so many incitements, were transplanted on Roman territory. Following the death of pro-Roman Artavasdes III, Augustus became aware of Parthia’s designs on Armenia. Augustus moved to thwart it. When Tiberius unexpectedly quit his responsibilities, Augustus chose his inexperienced adopted son, C. Caesar, to negotiate a nonaggression pact with Parthia. In this he succeeded. He also intervened to oversee the installation of a pro-Roman regent in Armenia. Meanwhile, the troublesome Getae were moved in their thousands to new land in Thracia.

The strategy of overseas expansion was to be continued in the fourth decade of imperium (3–12 CE), but its implementation was undermined by events. In the West, L. Caesar died while on manoeuvres. In the East, war in Armenia was abandoned when the Roman army’s wounded leader, C. Caesar, resigned his command and later died on the journey home. A strategic withdrawal was the best option. Iudaea became a concern on account of the poor handling of internal security by the unpopular Archelaos – King Herodes’ successor approved by Augustus. He acted decisively to seize the kingdom for his provincia, allowing him to intervene directly using troops from Syria should there be any future uprisings in this important district so close to the frontier with Rome’s arch-nemesis. In the North, complete annexation of Germania seemed attainable. Now returned from self-imposed exile, Tiberius planned a massive thrust into Bohaemium to eliminate the Marcomanni, seen as the last major strategic obstacle to completing the conquest of the region. He assembled the largest force in Roman history to encircle and crush the enemy. The invasion had to be abandoned because of a major rebellion of auxiliary troops in Illyricum. Perceived as the gravest threat since the Punic Wars, military resources were hurriedly redirected, supplemented by a levy of citizens and freedmen mobilized from Italy. Illyricum was saved only after a war lasting four years. Within days of its conclusion, news arrived of a revolt in Germania. The land and people recently considered pacified there were completely lost. In panic, Augustus prepared for an invasion of Italy by Germanic nations. It did not come. Punitive raids across the Rhine led by Tiberius and Germanicus Caesar enforced the Romans’ right of access, but no serious attempt to recover the former province would be launched for another five years. New Provinces of Caesar were created – Germania Inferior, Germania Superior, Moesia and Pannonia – and troops redeployed. Meanwhile, the Roman army and its allies successfully engaged bandits, rebels and foreign invaders in Africa, Cilicia, Iudaea and Sardinia.

In his last decennium (13–14 CE) of holding military power, Augustus adopted a much more cautious approach. An attempt at finishing the business in Germania was assigned to Germanicus Caesar. After a lifetime expending blood and treasure, Augustus set the limits to the imperium of the Roman People at their present positions, ‘fenced in by the sea, the Ocean and long rivers’.48 In the last clause of his handwritten breviarum, he insisted that his successor hold to that policy.49 The goal of enlargement had finally been replaced by one of conservation and co-existence – or so we are led to believe by Tacitus.

Where Augustus could achieve his aim without bloodshed, and the calculus made sense, he took that option.50 In Parthia, Rome had an adversary that matched her own prowess in war. Failure to understand this basic point meant several attempts to beat the Parthians in battle had failed disastrously. Iulius Caesar had a much better appreciation but was killed before he could execute the plan he had carefully detailed.51 The pragmatic Augustus understood that the neighbour to the east was the permanent occupant and that a diplomatic settlement was the best result that could be achieved. Agrippa may have laid the diplomatic groundwork, which led to Tiberius receiving back the signa, aquilae and prisoners of war from the Parthian king in 20 BCE. It is worth noting that while Augustus was in the region he did not attend the ceremony in person. That way, the Parthian ‘king of kings’ could not claim the Roman leader had sought supplications from him. Frahâta’s son was returned (along with the Italianborn slave Musa) in reciprocation.52 Armenia remained a contentious issue. The spat between Augustus and Frahâtak showed both sides could play the diplomatic game, and its chief protagonists knew when to stop short of injurious insults. In 1 CE, the Parthian king finally met Augustus’ envoy C. Caesar on an island in the middle of the Eurphrates in the ceremonies witnessed by Velleius Paterculus. Again Augustus was not there in person. The Romans now recognized the right of the Parthians to territory east of the Euphrates River. It was an important concession by the princeps. The parties also agreed that while Rome had an interest in nominating or approving the regent of Armenia, it did not require an army to be based there to enforce the terms. Should the situation call for armed intervention, Augustus had several legions (a quarter of his entire army) and auxiliary units stationed in Syria and Egypt. Augustus presented both achievements to his own people as great military victories – as demonstrations of his strength and resolve. In his Res Gestae, he specifically cites Armenia Minor, explaining that instead of annexing it into the empire after the assassination of its King Artaxes:

I preferred – following the precedent of our fathers – to hand that kingdom over to Tigranes, the son of King Artavasdes, and grandson of King Tigranes, through Ti. Nero who was then my stepson; and later, when the same people revolted and rebelled, and was subdued by my son Caius, I gave it over to King Ariobarzanes the son of Artabazus, King of the Medes, to rule, and after his death to his son Artavasdes. When he was murdered I sent into that kingdom Tigranes, who was sprung from the royal family of the Armenians.53

Achieving victory, so that he could present it to the Senate and Roman People, is what mattered most to Augustus.54 Tradition required that after battle the vanquished would engage in an act of unconditional surrender (deditio) and the victor would impose terms of a pact.55 To the Romans, this act defined a successful outcome of war. As an assurance of trustworthiness, the defeated would be required to hand over hostages (obses) (plate 39) and weapons.56 Their display was an essential aspect of celebrating victory. Celebrating the Pax Parthorum, Augustus enjoyed showing off the hostages he had received from the Parthian king.57 Coins presented this same image of surrender: a defeated leader, often on bended knee, raising his arms in supplication, offering up a battle standard or a child. The defeated barbarian warrior with hands tied behind his back, sitting beneath a tropaeaum, was a common motif on triumphal arches or inscriptions gracing war monuments (see plate 33).58 A dejected man and a distraught woman are shown in this pose in one of the scenes on the Gemma Augustea (plate 40), where a group of Roman soldiers erects the trophy, while others restrain a man and a woman by pulling on their hair. Once the decorated oak tree trunk is in position, these captives will join their countrymen in obeisance. Acknowledgement of the victor’s supremacy and showing deference to him were crucial behaviours in this power transfer ritual. Rome would willingly make an ally of those who accepted their subjection, but would brutally crush a people who did not or displayed arrogance (superbia).59

Failure to uphold the terms of the pact was an injury (iniuria) to Rome, which would be met with revenge (ultio).60 They were important reasons for waging wars of necessity – what the Romans called ‘just war’ (bellum iustum). Cicero explains, ‘no war is just, unless it is entered upon after an official demand for satisfaction has been submitted or warning has been given and a formal declaration made.’61 Notifying the enemy that a state of war existed between them and the Romans for a violation was the purpose of ancient fetial law and its officials (fetiales).62 Their arcane rite of declaring war, which had fallen into disuse during the late first century BCE, was re-established by the then Imp. Caesar to validate his war against Kleopatra. Thus it could be said:

[Augustus] never made war on any nation without just and due cause, and he was so far from desiring to increase his dominion or his military glory at any cost, that he forced the chiefs of certain barbarians to take oath in the temple of Mars Ultor that they would faithfully keep the peace for which they asked; in some cases, indeed, he tried exacting a new kind of hostages, namely women, realizing that the barbarians disregarded pledges secured by males; but all were given the privilege of reclaiming their hostages whenever they wished. On those who rebelled often or under circumstances of especial treachery he never inflicted any severer punishment than that of selling the prisoners, with the condition that they should not pass their term of slavery in a country near their own, nor be set free within thirty years.63

After beating the Salassi in 25 BCE, A. Terrentius Varro sold 8,000 war captives as slaves. Ten years later, Nero Claudius Drusus and his older brother forcibly transplanted the strongest men able to bear arms among the defeated Raeti, leaving just enough to cultivate the land – although many opted to serve with the Roman army as auxiliaries. In 12 BCE, when victorious in battle over the Pannonii in Illyricum, Tiberius sold most of the men of military age into slavery and deported them from the country. Such brute-force examples of social engineering changed these vanquished societies forever.

Victory did not have to mean utter destruction for the losing side. Augustus could be generous and show clemency (clementia) to the defeated. In Res Gestae, he claimed to have spared the foreign nations which he believed could be trusted to uphold their terms, preferring to save rather than to destroy them.64 Taking his lead, Augustus’ subordinates too could be merciful. When the Astures surrendered their stronghold of Lancia in 25 BCE, the Roman commander P. Carisius responded to lobbying and agreed to spare their lives. Tiberius permitted 40,000 Sugambri to relocate to Roman territory in 8 BCE. This also explains Tiberius’ response to Bato of the Daesidiates’ surrender in 9 CE: having freely offered himself and asked for no special treatment, the captive rebel leader was displayed in triumph three years later, but he was spared execution, granted a pension and permitted to live his life in peace. Many newly conquered peoples showed their allegiance when recruited as paid troops in native alae and cohortes. This is how the Astures, Breuci, Cantabri, Frisii, Ligures, Norici, Sugambri, Vindelici and others found their way into the Roman army, which benefited from employing their distinctive fighting styles to its advantage.

In other cases, Augustus presented his success as recovering what had once been Roman, such as Cyrenae, Sicily and Sardinia.65 The annexation of regions previously thought too remote or barbaric to be explored were a source of particular pride to him:

I extended the boundaries of all the provinces, which were bordered by races not yet subject to our imperium. The provinces of the Galliae, the Hispaniae and Germania, bounded by the Ocean from Gades to the mouth of the Albis River, I reduced to a state of peace. The Alps, from the region which lies nearest to the Adriatic Sea as far as the Tuscan, I brought to a state of peace without waging on any tribe an unjust war.66

He claims credit for his deputy’s explorations of, and exploits in, the furthest reaches of barbaricum:

My fleet sailed from the mouth of the Rhenus River eastward as far as the lands of the Cimbri to which, up to that time, no Roman had ever penetrated either by land or by sea, and the Cimbri and Charydes and Semnones and other peoples of the Germans of that same region through their envoys sought my friendship and that of the Roman People.67

In contrast, he writes simply: ‘Aegyptus I added to the imperium of the Roman People.’68 The matter-of-fact reporting is astonishing for the absence of any embellishment.

Augustus’ grand strategy – his military policy and its resourcing sustained over decades – did not evolve. It was the consistent use of ‘just war’. In pursuit of it he was not reckless. Indeed he was calculating, erring on the side of risk aversion. Most of the conflicts fought under his auspices were wars of necessity, undertaken in response to real threats (such as insurrection) or in self-defence (such as against invasions). Few were wars of choice or aggression. A war of conquest took years to prepare, execute and complete, and incurred a great cost in men and matériel. The exigencies of fighting particular campaigns and missions on the ground required adaptation and change in pursuit of successfully achieving the overall military objective. The adversary’s unconditional surrender was preferred over a policy of annihilation. Pacification could then follow through settler colonization, urbanization of native people, the inclusion of tribal élites into the Roman political system, the levying of taxes and tribute (which would include recruiting their warriors into the Roman army), and so on.

When he decided to embark on a just war Augustus had both the political will and ability to bring the military resources together to achieve a lasting victory. Compared to the consuls and praetors of earlier times, he had two distinct advantages. Firstly, the Senate granted him greatly extended periods of time in which to wield his military power, and renewed those terms when they expired. In turn the legates he personally appointed also served out field commands of several years. Thus Augustus could afford to take the long view. Secondly, the vast size of his province meant he could recruit the necessary numbers of men and animals and then replace his casualties campaign season after campaign season. As well as drawing upon contingents from treaty allies, he could further augment the ranks of his full-time professional troops – increasingly comprised of Romanized provincials rather than just Italians – with new units created from recently subjugated peoples.

A war of necessity could, however, become one of choice if ‘scope creep’ was allowed to cloud the clarity of the initial purpose. The Bellum Germanicum launched in 12 BCE was a response to invasions by coalitions of Germanic warriors raiding into Roman territory and the murder of Roman citizens peacefully trading across the Rhine. Subjugating the Sugambri, Tencteri and Uspietes might have been enough to address the military threat, but successive campaigns, driven by the irresistible chance for glory, lured the field commanders far beyond. A dictum of war is that it takes more combat power to hold an objective than to take it. It took the revolt of Arminius twenty-one years later to remind the Romans of the folly of carelessly applying the doctrine of imperium sine fine. If Augustus allegedly did temper his strategy within a year or two of his death, it was because he had finally come to realize there were limits to what he could do with the economy of force and budget under his control.

Augustus as Manager of War

Having assumed responsibility for a province, keeping it secure posed an immense challenge. Quoting an extract from the eulogy delivered by Tiberius at Augustus’ funeral, Tacitus reports:

Only the mind of the deified Augustus was equal to such a burden: he himself had found, when called by the sovereign to share his anxieties, how arduous, how dependent upon fortune, was the task of ruling a world! He thought, then, that, in a community, which had the support of so many eminent men, they ought not to devolve the entire duties on any one person; the business of the Res Publica would be more easily carried out by the joint efforts of a number.69

In this rôle, he needed a different set of skills. Augustus could not be everywhere at once, making decisions on matters great and small. Spread over three continents, separated by great distances and facing issues in real time, made delegating responsibility to subordinates not only practical but essential.70 As the military leader, his job was to inspire and motivate; his task as a manager was to plan, organize, coordinate and control. As the leader, Augustus had to take a longrange perspective; as a manager, the short-term would be more important, with a focus on the ‘hows’ and ‘whens’ needed to achieve results.

Structure follows strategy, according to modern management theory.71 In the past, a governor (proconsul or propraetor) was assigned a territory by the Senate and was answerable to the Conscript Fathers at the end of his term. Augustus created a three-tier command structure to manage his provincia. Its purpose was to execute the process of pacification and to deal with military exigencies as they arose. He inserted himself at the strategic level. To each of the nine – later more – geographically-based operational commands within it, he appointed a propraetorian legate (legatus Augusti pro praetore). This officer was responsible in turn for the tactical level legions and auxiliary units stationed there.72 Each legatus was semi-autonomous, empowered by Augustus to make decisions that affected his territory and army group. It was not actually a new approach. Pompeius Magnus had managed his extensive command when fighting the pirates this way, as had Iulius Caesar on a smaller scale in the Gallic War.73 Under the terms of the Lex Gabinia, Pompeius could operate up to 50 miles inland from the coast. However, this meant his provincia (task or military duty) overlapped with other proconsuls’ existing provinciae (territories). Rather than sub-divide his campaigns among the governors and be forced to act as a coordinator between them, he cunningly assumed overall strategic command and directed tactical operations through his own team of twenty-four legati, who were each imbued with imperium as provided for in the law.74 In effect, Pompeius created for himself a three-year command of a ‘super province’, directing over the heads of the annually appointed proconsuls – a provision the Senate almost certainly would not have agreed to when passing the law.75 The strategy had proved effective in crushing the menace of piracy. This precedent too was helpful to Augustus.

Governing an armed ‘Province of Caesar’ was a military assignment, and the job title and responsibilities reflected that fact. Augustus handpicked every one of the men for the posts of legatus Augusti pro praetore.76 In contrast, the proconsul of a ‘Province of the People’ was chosen by lot from among ex-consuls.77 In office, the legatus wore full military panoply, in contrast to the proconsul, who wore civilian attire of tunic and toga.78 Keeping his province ‘pacified and quiet’ was the legate’s most important task.79 As a direct representative of Augustus, he had the necessary military imperium to command all the army units stationed in his provincia, with every commander of an auxiliary unit reporting to him.80 The Roman army was not only the instrument of conquest and subjugation, but a province’s de facto police force as well.81 The legatus was invested with authority to exercise full powers at his discretion, including capital punishment.82 His tour typically lasted three years (triennium), which was longer than the one-year term of the proconsul of a senatorial province.83 He enjoyed a complement of five fasces-bearing lictors – one less than a proconsul, emphasizing his lesser status.84

The exception was Egypt. In 30 BCE, the then Imp. Caesar appointed a praefectus Aegypti to manage the province, command the army of occupation and report directly to him.85 As Rome’s strategically important breadbasket, Egypt had to be administered by someone who could never become a challenger to Augustus. Despite the indiscretions of the first man in that post, all subsequent appointments continued to be praefecti.86 Similarly, after its annexation in 6 CE Iudaea would be governed by a praefectus who would report to the legatus Augusti of Syria.87 Praefecti were recruited from among the equites to ensure that their allegiance lay with Augustus rather than with the Conscript Fathers. The appointment of equestrian superintendents in both jurisdictions signalled that they were lower status and relatively undesirable appointments compared to the provincial governorships given to senators, and that officers serving in these positions lacked both the dignitas and auctoritas of the legati Augusti.88 Nevertheless, these postings represented the pinnacle of a career for an eques.

As a manager, selecting the right people for his organization was Augustus’ most important task. His future success and reputation depended on the reliability of his subordinates in carrying out their broad mission. He had to trust them completely. Over forty-one years (27 BCE–14 CE), Augustus worked with three generations of men to run his province.89 The first generation was comprised of men who had fought with him at Actium and Alexandria, or aligned with him even before these episodes. He picked them from all classes. He cared only for ability. Many were patricians, such as Paullus Fabius Maximus and L. Sempronius Atratinus. He also chose and advanced commoners, the novi homines like M. Agrippa, Sex. Appuleius, L. Autronius Paetus, C. Calvisius Sabinus and T. Statilius Taurus.90 Remarkably, others had once been his enemies, like L. Domitius Ahenobarbus and M. Titius, but later defected to him. Individually, these men had a special bond with Augustus and would continue to enjoy his support and friendship (amicitia) for the rest of their lives. Many were accorded the special honour of being welcomed into the high status college of quindecemviri sacris faciundis headed by Augustus, whose members organized the Ludi Saeculares of 17 BCE.

The Actian War was the defining event that confirmed beyond a doubt the loyalty and stature of Augustus’ greatest general. M. Agrippa was his paragon of a deputy. He personified honour, courage, commitment, and above all unswerving loyalty. His equal in age, he also matched him in experience and temperament. They had been through a lot together. Agrippa was disarmingly modest yet faithful, almost to a fault, putting his life in harm’s way repeatedly in the service of his friend. His talents for organization and field combat leadership were without rival. Augustus trusted Agrippa so well he alternated command with him; when he went to the East his associate went West, and vice versa. T. Statilius Taurus was another loyal and talented commander upon whom he counted. Augustus could feel confident to leave Rome in his care as praetor urbanus in 16 BCE. Of these two men, Velleius Paterculus writes:

In the case of these men their lack of lineage was no obstacle to their elevation to successive consulships, triumphs, and numerous priesthoods. For great tasks require great helpers, and it is important to the Res Publica that those who are necessary to her service should be given prominence in rank, and that their usefulness should be fortified by official authority.91

The second generation comprised his own stepsons, Nero Claudius Drusus and Tiberius, and their contemporaries such as A. Caecina Severus, L. Calpurnius Piso (Piso the Pontifex), Cossus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus, P. Quinctilius Varus, C. Sentius Saturninus and M. Valerius Messalla Messallinus. The Claudius brothers both proved to have natural talent for command and were popular with their troops. When Agrippa died, Tiberius proved to be a risky, but ultimately fine surrogate. Younger, and with a history very different than Agrippa’s, he was more temperamental and less imaginative. Yet he proved as dedicated and as reliable in military matters. Once rehabilitated from his retirement he returned to form, assuming the burden of command as Augustus aged – and never wavered.

The third generation of subordinates included C. Caesar, L. Caesar and Germanicus, whom Augustus mentored himself. They were starting their military careers when he was already in his sixties. ‘The younger men had been born after the victory of Actium,’ writes Tacitus, ‘most even of the elder generation, during the civil wars; how few indeed were left who had seen the Res Publica.’92 When the young Caesar brothers died prematurely, Augustus turned to Tiberius and Germanicus Caesar to promote his policy in the field.

Augustus was not coy about exposing his own family to death. To be successful in public life in Ancient Rome, a man had to able to display virtus, and that could only truly be earned on the battlefield, witnessed by his countrymen. Augustus understood the risks. With that in mind, he always maintained a fallback position. If he died, Agrippa could assume leadership. If Agrippa died, Tiberius could take over. Unfortunately for Augustus he had a large measure of bad luck, losing his nephew Marcellus, son-in-law Agrippa, stepson Nero Drusus and adopted sons Caius and Lucius. Yet of these, only two men actually died from wounds sustained in battle (Drusus and Caius) – the rest having fallen victim to sickness, ironically picked up while on, or travelling from, campaigning. His calculus was sound in that at the time of his death two men of outstanding talent (Tiberius and Germanicus) still remained to execute his grand strategy. Nevertheless, it was a high-risk approach to succession planning.

The last time Augustus led his troops in person on the battlefield was during the Cantabrian campaign of 26 BCE. Sickness caused him to withdraw, and he delegated prosecution of the war to C. Antistius Vetus and P. Carisius. Why he entrusted the field leadership of all future military operations to his deputies can only be surmised. His health and fitness were certainly factors in his decision. It was not age: Agrippa was older by several months and would be active in combat operations for years to come. It was not lack of self-confidence: he had that in abundance. Nor was it cowardice: he had put himself in harm’s way often enough in his lifetime, even sustaining wounds in doing so. It is more likely that, ever the pragmatist, he recognised that his legati were now abler than he was at executing prolonged combat offensives. For the system to work Augustus had to step back and let the men he had picked get on with their jobs. He had empowered them to respond to security threats as they deemed appropriate. To be successful he had to resist the temptation of micromanaging them.

The majority of men who commanded in the wars fought on Augustus’ behalf served as consul.93 Keeping the bench of talent full was an ongoing challenge. His frequent censorial reviews of the Senate resulted in removal of many unsuitable men while revealing new potential candidates for command positions, men like C. Poppaeus Sabinus, P. Sulpicius Quirinius and L. Tarius Rufus.94 Reducing the qualification age was another expedient Augustus tried in order to expose men to military service at a younger age than was customary:

To enable senators’ sons to gain an earlier acquaintance with public business, he allowed them to assume the broad purple stripe (latus clavus) immediately after the toga of manhood and to attend meetings of the Senate; and when they began their military careers, he gave them not merely a tribunate in a legion, but the prefecture of an ala of cavalry as well; and to furnish all of them with experience in camp life (expers castrorum), he usually appointed two senators’ sons to command each ala.95

Commanding between 512 and 768 adult men would be a significant responsibility for a man in his late teens or early twenties and, doubtless, a lifetransforming experience.

In parallel, he picked men of the Ordo Equester exclusively to fill vital positions of trust, notably the praefecti of Egypt, the Praetorian Cohorts and the Vigiles.96 Augustus was eager to repurpose the faded order as a new military class. It was once formed of men equipped with horses at public expense to support the legions, but had long since become a ‘club’ of advocates and bankers eschewing the battlefield for the basilica. ‘To keep up the supply of men of rank and induce the commons to increase and multiply’, Augustus ‘admitted to the equestrian military career those who were recommended by any town’ in Italy.97 Men who had served as centurions in the army could be promoted into the order.98 To reestablish its prestige, he reintroduced the traditional transvectio parade after it had fallen into disuse.99 Significantly, he appointed his own sons in turn to be princeps iuventutis (‘the first of the youth’), ranked a sevir turmae in charge of one of the six turmae of iuniores.100

To foster a pro-military mindset in the younger generation, Augustus urged Roman boys to adopt the warrior’s values of courage, honour and the rest. He encouraged participation in the traditional paramilitary exercises, which were performed for the public:

he gave frequent performances of the Game of Troy (Lusus Troioae) by older and younger boys, thinking it a time-honoured and worthy custom for the flower of the nobility to become known in this way. When Nonius Asprenas was lamed by a fall while taking part in this game, he presented him with a golden torque and allowed him and his descendants to bear the cognomen Torquatus.101

Through his semi-autonomous legati, Augustus was able to develop, adapt and revise strategies for pacification and annexation in different theatres simultaneously. Remarkably, these were not career military men. During their working lifetimes they alternated between civilian and command positions. Rising through the cursus honorum, they could serve as a military tribune, prefect and legionary legate, and at other times work as a quaestor carrying out financial audits, an aedile arranging road repairs or as a praetor overseeing a case at a law court. When faced with military threats – banditry, migrant invasions, revolts – or leading wars of conquest, these men did so to the best of their abilities. During their terms, many legati Augusti would see just one combat season. The burden of fighting war did not fall on the shoulders of all legates equally, however. Several fought in multiple campaigns, notably: Agrippa (31, 19, 14 and 13 BCE); L. Calpurnius Piso (13–11 BCE); Nero Claudius Drusus (15 and 12–9 BCE); Sulpicius Quirinius (15, 5 BCE and 2–3 CE); and Tiberius (15, 14–13, 8–7 and 4–5 BCE, 6–9 and 10–11 CE). Of his praefecti Aegypti, Cornelius Gallus repulsed a bandit raid (30 BCE), Aelius Gallus fought a single war in Arabia Felix (24 BCE), but Petronius undertook campaigns over three seasons (25–24 and 23 BCE).

Suetonius provides a fascinating insight into the behaviours Augustus valued in his legati:

He thought nothing less becoming in a well-trained leader than haste and rashness, and, accordingly, favourite sayings of his were: ‘More haste, less speed’; ‘Better a safe commander than a bold’ [in Greek]; and ‘That is done quickly enough which is done well enough.’102

His preference was clearly for level-headedness, preparedness, steadfastness and thoroughness. Consistent demonstration of these traits could take a subordinate far. It was an idea embodied in the Roman virtue of moderatio – the avoidance of extremes, the showing of restraint and the power of self-control.103 Cicero regarded it as the appropriate quality for a man serving in public office.104 Agrippa lived by it and so too did Tiberius.105 In contrast, L. Domitius Ahenobarbus was the antithesis of moderation. His reputation for haughtiness, extravagance and indifference to pain and suffering was a liability. It hindered, for example, his ability to negotiate with the Germans for the return of prisoners in 1 CE. It extended to his taste for beast hunts and gladiatorial games, where he displayed ‘such inhuman cruelty that Augustus, after his private warning was disregarded, was forced to restrain him by an edict’.106 Yet despite his distasteful antics, Augustus could not dismiss or unfriend Ahenobardus; the man got results in Germania, for which he earned himself a triumph. There was still a place for such men in Augustus’ military organization. He was not naïve. War was a dreadful business; he knew that from personal experience. Someone had to do the dirty work. To be successful he needed ‘tough bastards’ too who could commit detestable acts without flinching. Even cultured Germanicus authorized vastatio against the Marsi in 14 CE – not for any atrocity the Germanic nation had committed, but to restore morale among his troops. Like any manager today, Augustus did not like surprises. He would also introduce controls to change excessive behaviours, as shown by the mandated requirement for his subordinates to invest some of their war spoils in buildings and works that would benefit the public, not just themselves.

The majority of Augustus’ legati performed their duties well, several with distinction. In an organization as large and enduring as Augustus’, however, there were bound to be exceptions. M. Lollius was taken by surprise in 17 BCE when ambushed by Germanic raiders. It was, perhaps, more a case of accident than incompetence, but the loss of the aquila of Legio V Alaudae was unforgivable to the princeps. The track record of this enemy-turned-friend was, until then, unblemished. He had successfully managed the transfer of Galatia from the late king Amyntas’ estate to the imperium of the Roman People. But the blunder in Belgica (or Gallia Comata) was an acute embarrassment to the man who had boasted the achievement of reclaiming the signa lost by Crassus at Carrhae just three years before. The Tres Galliae would be Lollius’ last command. He was replaced by Tiberius. Lollius avoided the enmity of the princeps and later was appointed to accompany his adopted son to the East. It was then revealed that he had received bribes from the Parthians. From that moment nothing could save him. Redemption would take the form of a self-inflicted wound or a draught of poison. His ward too disappointed. C. Caesar proved inadequate to the high-profile command he had been given. Inexperience or unsuitability for the role combined with bad luck to expose him to mortal danger. Injured by a battle wound, his character buckled and he resigned his commission. He died on the journey home. In comparison, Quinctilius Varus was an accomplished field commander. He had served as a legionary legate in the Alpine War of 15 BCE and quelled a rebellion in Iudaea in 4 BCE as legatus Augusti of Syria. He should have been more alert in Germania. Ambushes were the ever-present danger to Roman troops on the march, yet he took no precautions. He even failed to heed a tip-off from reputable source and dismissed it. He lost his life to his own sword – and Germania with it. Thus Augustus suffered a second military humiliation by his own subordinates.

Roman commanders seemed to perform less well when they were acting on the defensive (reacting to a threat). Even a general as experienced as Tiberius could be caught out when marching full stride towards Bohaemium, when he learned of the uprising in Illyricum in 6 CE. Tiberius had fought several campaigns in the Western Balkans and knew the people, so the unwelcome surprise is itself surprising. This likely points to a failure of ground intelligence gathering by the legatus Augusti of Illyricum, M. Valerius Messalla Messallinus. This was his first provincial command. The inexperience of certain legati Augusti in combat, however, was a weakness of the Augustan system. When Caecina Severus and Silvanus arrived with their contingent, the rebels were waiting for them. In the ensuing ambush, the casualties included a tribunus militum, a praefectus castrorum, a primus pilus and other centurions of the legions, plus several praefecti of auxiliary cohorts. Only the discipline and cool-headedness of the lower-ranking legionary centurions and the soldiers managed to turn the situation around and prevent it from descending into a complete rout. Having recovered, Severus promptly marched into a second trap at Volcaean Marshes when his camp was surrounded by rebels, but this time he managed to repel them.

The strength of the Augustan military organization showed itself when Tiberius could rapidly pull together resources from Moesia and Thracia to come to his assistance. It would seem from this example that the territory-based threetier organization structure allowed communication to be routed directly to the neighbouring command rather than having to seek permission from Augustus first, which might cause serious delay. The arrangement was facilitated by personal relationships, which mattered very much in Ancient Rome. Throughout their careers, men of similar age competed for political appointments in the cursus honorum. From their first professional steps in public life they would have known of each other, either forming friendships or developing rivalries. While they would know each other’s strengths (and weaknesses), as legati of Augustus each would come to a colleague’s assistance when asked, as demonstrated in Illyricum in 6 CE.

Relationship-building extended to non-Romans as well. Allies played an important role in Augustus’ strategy.107 Though bound by treaty, the princeps respected the independence of his alliance partners. Many of their sons gained an education in Rome under Augustus’ hospitality. Rome stood to benefit, of course. When the allied leader died, his territory might be bequeathed to the Roman People. This was the case with King Amyntas in 25 BCE. The realm passed peacefully into the control of the Roman People, overseen by Augustus’ legate M. Lollius. In wartime, allies could be called on to provide troops. During the war of 6–9 CE in Illyricum, at the request of Caecina Severus, Roimetalkes brought his Thracian warriors to assist. It was a reciprocal arrangement. When Sitas, the blind king of the Dentheleti, requested help to fend off the Bastarnae in 30 BCE, M. Licinius Crassus was obliged to respond. The following year Rolis, king of the Getae, who had helped Crassus defeat the Bastarnae, himself called for assistance. When the king later visited Augustus, he was treated as a friend and ally on account of his service to the Romans. Agrippa formed a close friendship with the irascible King Herodes of Iudaea. When Agrippa (known to have a quick temper himself) needed help to suppress the Scribonian Revolt in the Cimmerian Bosporus in 14 BCE, he only had to write a letter to the regent and a fleet of ships and marines appeared, following him to Sinope. Agrippa had already requested another ally, Polemon Pythodoros, to go to the source of the trouble and contain it. On occasions the ally with a higher agenda could manipulate the unwary Roman commander. Petronius was thoroughly duped by Syllaeus, who was secretly working for the advantage of Nabateans, an act of treachery which cost several thousand Roman lives and the deceiver his head. Quinctilius Varus trusted the Cherusci-born Arminius (who, though a hostage, had been educated in Rome) and Segimerus too much and was tricked into leading his army into a fatal ambush in 9 CE.

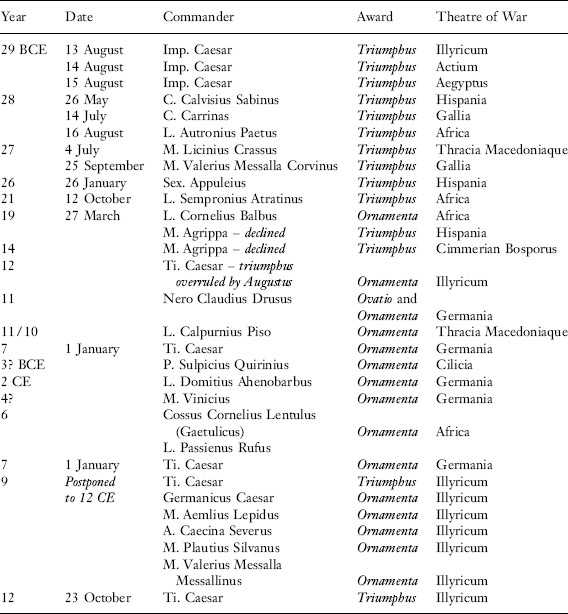

Augustus understood the value of rewards and recognitions to encourage high performance by his team members. He had learned that powerful men do not respond to threats, so he appealed to their vanity. By carefully controlling the number and distribution of awards, he greatly increased their worth. Competition for prestige and public recognition had been one of the factors in Rome’s military success. Under Augustus, commanders still competed hard for the distinction of a triumph. For a day a commander enjoyed the adulation and congratulations of his fellow citizens in a glittering military parade in the centre of Rome. Between 31 BCE and 14 CE, more than thirty triumphs were awarded and ‘the triumphal ornaments to somewhat more than that number’ (table 6).108 About a third of these took place during the first decade of Augustus’ imperium, the phase during which his generation occupied the highest positions of command. The most magnificent was, of course, Augustus’ own triple triumph of 29 BCE, an event intended to rival Pompeius Magnus’ and Iulius Caesar’s, or outdo them. The other events rewarded the old guard for wars fought in Africa, Hispania Citerior, Macedonia, Thracia and Tres Galliae.109 One was declined by the triumphator M. Agrippa himself, whose deeply ingrained sense of modesty prevented him from accepting. Eager to celebrate his, Sempronius Atratinus was the last privatus to be granted a full triumph with a quadriga in 21 BCE. In the next ten-year term, Agrippa turned down another triumph, while, at Augustus’ insistence, one granted to Tiberius was downgraded to triumphal ornaments. His brother received an ovatio, which permitted him to ride a horse along the Via Sacra, along with triumphal ornaments. These men had grown up in a different era; they were young boys when Augustus celebrated his triumphs and had even taken part in them. They did not need such ostentatious enticements to perform in the field as the older generation of viri triumphales had, yet they were still highly attractive prizes to this younger generation of commanders eager for recognition.110 In the third and fourth periods, the frequency of these distinctions changed from every two or three years to three to five. Tiberius was the last man to be honoured with a full triumph for crushing the revolt in Illyricum of 6–9 CE. It was postponed to 12 CE on account of the Varian Disaster.

The award of war titles (cognomina) was a rarer honour in Roman history. Augustus curtailed the practice further. Cossus Cornelius Lentulus was permitted the unique war name Gaetulicus in 6 CE for his victory over the African tribe, but Tiberius was denied one for Illyricum, which might have seen him called one of several names including Pannonicus. Nero Claudius Drusus posthumously received the title Germanicus. It was hereditary and adopted by his eldest son as his first name.

Table 6. Triumphs and Ornaments Awarded, 31 BCE–14 CE.

Sources: Appendix 2; Fasti Triumphales Barberini; Fasti Triumphales Capitolini, Dio; Suetonius; Boyce (1942); Hickson (1991); Itgenshorst (2004); Wardle (2014).

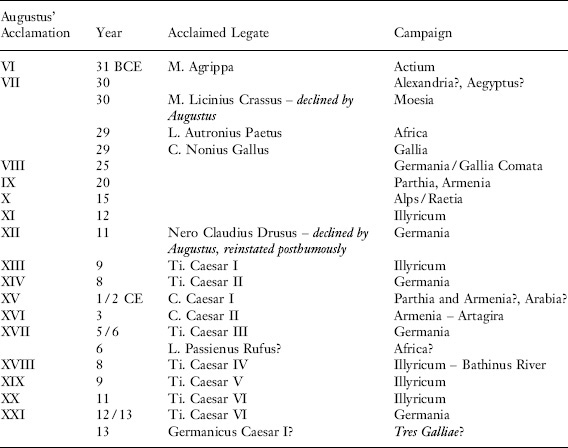

Another form of recognition Augustus tightly controlled was the acclamation. Traditionally it was in the gift of the soldiers after battle to shout out ‘imperator’ in praise of their commander for leading them to victory. By 31 BCE, the then Imp. Caesar had himself received six acclamations, including one for Actium (table 7). The following year he picked up another in Egypt. That year he denied Licinius Crassus this honour – but offered him triumphal ornaments – yet the following year he permitted L. Autronius Paetus and M. Nonius Gallus to retain theirs. From that time on, the acclamation was considered Augustus’ privilege alone and the running tally was displayed on coins. The only exceptions were Tiberius, C. Caesar and Germanicus (Drusus having been denied his but allowed it posthumously), but in these cases the princeps also counted them towards his running total. By 14 CE, he had garnered an unprecedented twenty-one acclamations.111

Table 7. Imperatorial Acclamations of Augustus and His Legates, 31 BCE–14 CE.

Sources: Appendix 2; Barnes (1974); Swan (2004); Wardle (2014), with author’s revisions based on Dio and other Roman sources.

The highest honour a Roman citizen could win in wartime was to take the spolia opima or ‘rich spoils’ of a defeated enemy leader. Courageous Roman commanders sought to emulate city founder Romulus’ exploit of slaying King Acron by his own hand and stripping him of his blood-spattered panoply. It was an exclusive club, which made the prize extremely desirable. Only two men had since succeeded: A. Cornelius Cossus in either 437 or 426 BCE; and M. Claudius Marcellus in 222 BCE. Just two years after Actium, M. Licinius Crassus killed the king of the Bastarnae in combat when his army crossed the Danube River and it was intercepted by the Romans. Crassus claimed the right to deposit his spolia opima in the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius. For the heir of Iulius Caesar it posed an awkward political dilemma. He had inherited the dictator’s rights to the practice and was the restorer of Jupiter’s temple, yet at the time was still seeking to establish his credentials. He insisted that the rules had to be followed. Since Crassus did not report to him as his commanding officer, he could not authorize deposit of the spoils.112 Crassus was offered a triumph instead. Two decades later, Augustus’ own stepson Nero Claudius Drusus attempted to follow in the great tradition in the fields of valour of Germania. There is no record that he succeeded.

Augustus had a deep respect for the chain of command and believed that men should follow orders. He was known as ‘a strict disciplinarian’.113 Intended to enforce discipline (disciplina), martial law could be applied particularly harshly in the military zone (militiae) – on the march, in camp, on the battlefield – and the protections afforded citizens under civil law did not apply.114 Suetonius provides several examples of Augustus’ expectation of complete obedience and the punishments he meted out for violations:

He dismissed the entire Legio X in disgrace, because they were insubordinate, and others, too, that demanded their discharge in an insolent fashion, he disbanded without the rewards which would have been due for faithful service. If any cohorts gave way in battle, he decimated them, and fed the rest on barley. When centurions left their posts, he punished them with death, just as he did the rank and file; for faults of other kinds he imposed various ignominious penalties, such as ordering to stand all day long before the legate’s tent, sometimes in their tunics without their sword-belts, or again holding ten-foot poles or even a clod of earth.115

His deputies followed his example, as Agrippa did in the Cantabrian War of 19 BCE when he stripped Legio I of its honorfic title Augusta.

Unlike his mentor Iulius Caesar, Augustus believed there should be some distance between himself and the rankers. He preferred to address them as milites or ‘soldiers’, not by the more familiar commilitiones or ‘fellow soldiers’ – ‘thinking the former term too flattering for the requirements of discipline’ – and went so far as to instruct his own sons and stepsons to do likewise.116 In reciprocity, he refused to be addressed by anyone as dominus – ‘master’ – because it inferred a servile relationship and he was ‘only a man’.117 ‘As patron and master he was no less strict than gracious and merciful,’ writes Suetonius, ‘while he held many of his freedmen in high honour and close intimacy, such as Licinus, Celadus, and others.’118

Augustus was aware of the importance of kind words in encouraging high performance from his direct reports. The letters he wrote to Tiberius (quoted by Suetonius) reveal that. He could also show forgiveness when it was appropriate.119 In his Res Gestae he writes that ‘when victorious I spared all citizens who sued for pardon’.120 Though replacing Lollius as Legatus Augusti in Tres Galliae after his embarrassing ambush, Augustus still had enough confidence in the man that he later appointed him as mentor to his adopted son C. Caesar on his mission in the East. When he learned that his slave Cosmus had spoken in most insulting terms of him, ‘he merely put [the man] in irons’.121

In return Augustus demanded complete loyalty from his people, whether citizen, freeborn, freedman or slave. Disloyalty or treachery led to swift retribution. As soon as the same Lollius was discovered to have taken bribes from the Parthians, he was recalled to Rome to face trial. Gallus, the praefectus Aegypti, met a similar end for his indiscretion. When freedman Thallus was discovered to have been paid a bribe of 500 denarii to betray the contents of a letter, Augustus ordered his legs broken.122 While he could be clear-headed and calculating, he could also be highly emotional. He could explode into bouts of anger, especially with his close friends, and he lamented that he could not control it in their presence.123 Most famously, on hearing the news of the disaster in Germania he cried: ‘Quinctilius Varus give me back my legions!’ In this regard, Maecenas was a moderating influence when the princeps’ temper got the better of him.124 His deputies were an assortment of temperaments: Agrippa was bashful, but impatient; Aelius Lamia kindly; Calpurnius Piso (Piso the Pontifex) willing to compromise; Cornelius Balbus showy; Domitius Ahenobarbus arrogant and cruel; Marcius Censorinus very likable; and Tiberius was brooding and intense, to describe but a few.

Augustus involved himself directly and personally in the planning of military affairs. Rome’s enemies posed threats both within and without the border constantly. Immediately after Actium, military actions were ad hoc, mostly responses by local commanders to quell unrest among peoples already subject to Roman rule and to block raids by foreign invaders. His decision to redeploy legions in 30 BCE while in Brundisium indicates that he was ready to deal with the present threats to the nation’s security. It also reveals that he was thinking longer-term and was positioning the troops where he needed them to be as part of a larger strategic plan.

Before committing to a military campaign, Augustus conducted what could be called a strategic risk assessment. Suetonius preserves his dictum of the ‘golden fish hook’ (aureo hamo piscantibus):

He used to say that a war or a battle should not be begun under any circumstances, unless the hope of gain was clearly greater than the fear of loss; for he likened such as grasped at slight gains with no slight risk to those who fished with a golden hook, the loss of which, if it were carried off, could not be made good by any catch.125

To improve the chances of success in war, he believed in bringing overwhelming force (vis maior) to bear on an opponent. The campaigns in Cantabria (26–25 BCE), Germania (12–9 BCE) and Illyricum (6–9 CE) brought together some of the largest numbers of legions and auxiliary units ever assembled. The army groups might be split to execute pincer movements, as in the war planned against the Marcomanni (which had to be abandoned) or in the war against the Astures and Cantabria. In these actions, coordination between the commanders was crucial to ensuring the objective of encircling and crushing the enemy was achieved. Augustus also believed in patience. Actium was the epitome of this type of battle. Both sides faced each other on dry land for months before finally engaging upon the sea. A war might take years to accomplish the final goal – speed was secondary to quality of the result.

Comparing the campaign to annex Germania with the pacification of Illyricum makes for an interesting case study. In 27 BCE, there was no strategic imperative to acquire the lands east of the Rhine. Tacitus would later ask rhetorically:

Who would leave Asia, or Africa, or Italia for Germania, with its wild country, its inclement skies, its sullen manners and aspect, unless indeed it were his home?126

Roman commanders were reluctant to involve themselves in protracted military engagement in what was for them the unknown. On two occasions (in 55 and 53 BCE), Iulius Caesar constructed a wooden pontoon bridge across the river and

M. Agrippa followed him some years later (in 39/38 or 19/18 BCE). Neither general conducted their missions for conquest, but in response to pleas for intervention from the Ubii, an ally of the Romans. The ambush of Lollius in 17 BCE by Germanic bandits on Roman territory seems to have been the tipping point that caused Augustus to re-evaluate policy in the region. Augustus relocated to Colonia Copia Felix Munatia for some portion of the four years he was away from Rome, and took Tiberius with him. Having acquitted himself well in the Bellum Alpium, Nero Claudius Drusus was appointed to lead operations. Augustus would certainly have discussed the details of the invasion plan with them.

Successive explorations had established its boundaries:

Germania is separated from the Galliae, Raeti and Pannonii by the rivers Rhenus and Danuvius; from the Sarmatae and Daci, by mountains and mutual dread: the rest is surrounded by an ocean, embracing broad promontories and vast insular tracts, in which our military expeditions have lately discovered various nations and kingdoms. The Rhenus, issuing from the inaccessible and precipitous summit of the Raetic Alps, bends gently to the west, and falls into the Northern Ocean.127

Before these wars, much less was known about it. Roman commanders had maps but their detail and accuracy at this period is generally believed to have been poor.128 In the case of Germania, its scale confounded the geographers of the ancient world. To compile the current state of knowledge, Agrippa had assembled a team of Greek scholars to create a ‘Map of the World’ (Orbis Terrarum).129 About Germania, Pliny the Elder writes:

the dimensions of its respective territories it is quite impossible to state, so immensely do the authors differ who have touched upon this subject. The Greek writers and some of our own countrymen have stated the coast of Germania to be 2,500 miles in extent, while Agrippa, comprising Raetia and Noricum in his estimate, makes the length to be 686 miles, and the breadth 148.130