Sources: Maxfield (1984), p. 161; Wardle (1990), p. 195. This list is not exhaustive.

Table 9. Comparison of Roman Military Installations and Garrisons.

| Installation | Area (hectares) | Garrison |

| Carnuntum | 58 | 2–3 legions plus auxilia |

| Oberaden | 56 | 2 legions plus auxilia |

| Dorsten-Holsterhausen | 50 | 2 legions plus auxilia |

| Nijmegen-Hunerberg | 42 | 2 legions plus auxilia |

| Marktbreit | 37 | 1–2 legions plus auxilia |

| Noevaesium | 27 | 1 legion plus auxilia |

| Anreppen | 23 | 1 legion |

| Haltern | 18 | 1 legion or part thereof |

| Folleville | 16 | 1 legion or part thereof |

| Dangstetten | 13 | 1 legion or part thereof |

| Annaberg | 7 | 1–2 cohorts |

| Olfen | 5 | 1–2 cohorts |

| Hedemünden | 4 | 1–2 cohorts |

| Rödgen | 3 | 1 cohort |

| Beckinghausen | 2 | 1 cohort |

Sources: Bishop (2012); Delbrück (1990), p. 142; Keppie (1998); Kühlborn (2004); von Schnurbein (2000; 2002; 2004). For comparison, the maximum size of a football pitch is 120m×90m. This is an area of 10,800 id="mk2"m2; 1 hectare ¼10,000 id="mk2"m2. A full-size pitch could be 1.08 hectare.

Technical innovations to legionary arms and equipment occurred during Augustus’ time as commander-in-chief. These were likely developed to address specific tactical threats, such as enemy weapons or fighting styles, by adding or modifying equipment as soldiers always do in wartime. Success with a new design would spread within one unit as men copied the idea. Perhaps with the approval of the praefectus castrorum, it could be deployed across a single legion and then replicated across an entire army group. This may explain the changes in head protection (casis, galea), particularly in the northern frontier region. Its design changed from the helmet made of bronze popularly known as the Montefortino (plate 19), in widespread use in 31 BCE, to the so-called Coolus style with a separate eye/brow guard to deflect blows to the face and a wider neck guard, and finally to the so-called Weisenau (or ‘Imperial Gallic A’) made of iron, with detailing at the front and back to strengthen the dome.179 Body armour in common use among legionaries was a shirt of riveted links (lorica hamata) or scales (lorica squamata). From c. 15 BCE, a new form of articulated, segmented plate armour (the so-called lorica segmentata) was introduced (plate 21), and archaeological finds show that it was worn by some troops in the Alpine and German Wars.180

Roman soldiers faced an array of opponents fighting with different weapons and combat styles. Much as the Romans supposed themselves invincible, they were to learn the hard way under Augustus’ auspices that not all barbarians were created equal. Far from being inept, their diverse enemies could be resourceful, skillful and victorious. A Cheruscan infantryman dressed only in textiles and carrying a crude wooden shield for protection made up for his poverty of armour with agility in the use of the framea and prowess in irregular warfare. The Cantabrian cavalryman charged with his compatriots arrayed in tight formation, and could turn in an instant to spear his opponent. Native war fighters trained long hours to master technique, becoming professionals in their own right. Eschewing the set-piece battle for guerrilla warfare, they could stall the advance of legionaries equipped and trained to fight on the open plain or to besiege a stronghold. In arid valleys, dense forests and rocky mountain ranges across Europe, they launched ambuscades upon lines of marching Roman troops where they were at their most vulnerable. Sometimes their foes – like Arminius or Bato – were natives trained in Roman combat doctrine. They knew how to inflict maximum damage. Roman commanders – like Tiberius and his brother – were forced to rethink tactics to deal with their adversary. They knew they had to win. The recruitment of troops into native alae and cohorts not only placed large numbers of tribesmen where they could be controlled, but their myriad fighting styles could balance out the asymmetry of warfare – pitting barbarians working for Romans against other barbarians who did not. Augustus’ innovation was to recruit them in numbers not seen before (see Appendix 3.4). Earning less money than the legionary soldiers, the auxilia could be more cost-effectively deployed to augment the economy of force represented by the legions (table 10).

Table 10. Military Manpower, 31 BCE and 14 CE (Estimates).

| Unit | 31 BCE | 14 CE |

| Germani Corporis Custodes | 500? | 500? |

| Cohortes Praetoriae | 8,000 | 10,000 |

| Legiones | 300,000 | 150,000 |

| Auxilia | 80,000 | 150,000 |

| Classes | 75,000 | 45,000 |

| Cohortes Ingenuorum / Cohortes Voluntariorum | 5,000 | 23,000 |

| Cohortes Urbanae | – | 4,000 |

| Vigiles Urbani / Cohortes Vigilum | – | 6,000 |

| Total | 468,500 | 388,500 |

Sources: Appendix 3.

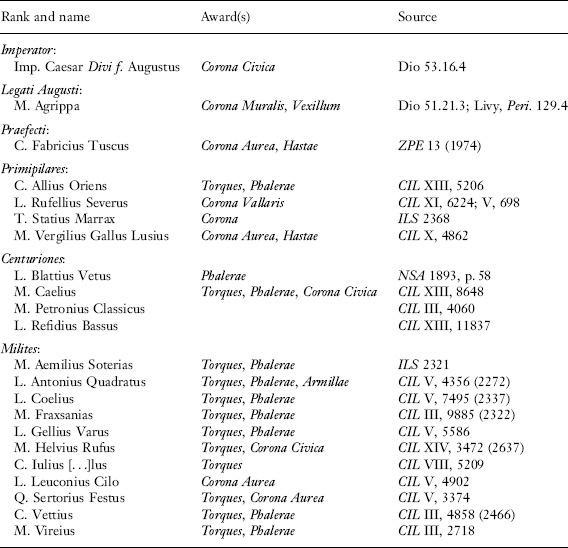

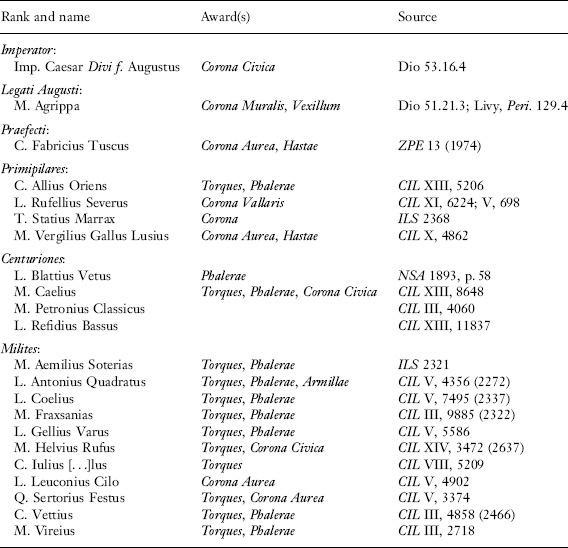

Regular pay motivated the majority of troops of Augustus’ standing army to risk their lives, but public recognition could raise ordinary performance in ways financial compensation alone could not. Honour-bound to look out for the welfare of his comrades in battle, a soldier witnessed amazing acts of bravery and courage by men in his unit, reinforcing the sense of brotherhood and belonging. Military decorations (dona) rewarded exceptional performance or dedication beyond the call of duty among the lower ranks. Several types were awarded. When deserved, Augustus personally issued them to troops and encouraged his sons to do the same, as Tiberius did in Germania, Illyricum and Pannonia:

As military prizes he [Augustus] was somewhat more ready to give phalerae or torques, valuable for their gold and silver, than coronae for scaling ramparts or walls, which conferred high honour; the latter he gave as sparingly as possible and without favouritism, often even to the common soldiers.181

(These distinctions were denied to the legati Augusti.)182 To judge by the few recorded examples dating to the Augustan period that have come down to us, all grades in a legion participated (table 11). A praefectus and primipilares personally led their men in attacks on military installations, earning themselves coronae, and at least one centurion saved the life of a compatriot. The primipilus M. Vergilius Gallus Lusius received his two spears (hastae) without iron heads and a golden crown (corona aurea) in person from Augustus and Tiberius.183 Many ordinary soldiers also engaged in acts of courage, earning themselves multiple decorations. L. Antonius Quadratus was decorated twice by Tiberius.184

While Roman troops fought gallantly to pacify unruly foreign lands, security for people living in the Italian homeland was often patchy in the first decades of Augustus’ principate. The capital city was effectively a demilitarized zone where armed soldiers did not patrol. Perhaps in part due to this, Rome remained a dangerous place for its inhabitants. In 47 BCE, fully three years before Iulius Caesar’s assassination, the consuls were compelled to ban anyone from openly carrying weapons within the pomerium.185 Yet there were still several attempts on Augustus’ life, and he felt sufficiently at risk that he wore armour under his tunic while attending meetings of the Senate and took his bodyguard with him at other times and places. There were several conspiracies to assassinate him or Agrippa – plots are recorded in 31, 22 and 18 BCE, and one as late into his principate as 4 CE. His investigators (speculatores) seem to have been highly effective at foiling these attempts (see Appendix 3.1). Finally enacted under Augustus, the Lex Iulia de Vi Publica made it illegal to collect weapons in houses in the city and the country, except for those customarily used for wild game hunting or taken on trips by land and sea for personal safety.186 Specifically to maintain peace and order in Rome, Augustus introduced the paramilitary Cohortes Urbanae or ‘City Cohorts’ (see Appendix 3.7).187 When he put on games in 2 CE, he deployed guards throughout the city to ensure thieves did not help themselves to people’s property.188 During the months following the ‘Disaster of Varus’ of 9 CE, the urbaniciani maintained patrols (excubiae) through the night.189

Table 11. Military Awards Issued, 31 BCE–14 CE.

Sources: Maxfield (1984), p. 161; Wardle (1990), p. 195. This list is not exhaustive.

Augustus claimed to have rid the seas of pirates.190 Dio, however, reports that in 6 CE pirates overran the coastal communities of the western Mediterranean, casting doubt on the princeps’ assertion. Travellers going by road could still be assaulted, robbed, taken hostage for ransom or even murdered. Brigandage was a problem in several parts of the Roman world at the time of Augustus, notably in Cilicia, Gallia Cisalpina and Hispania Citerior. Latrocinium covered violent armed robbery committed by latrones or bandits; if caught, they could face a range of punishments up to execution.191 Below them were the grassatores, footpads or muggers, who often operated in gangs (factiones); capture would entail time in the mines or exile, but not usually execution. Suetonius’ report states:

Many pernicious practices militating against public security had survived as a result of the lawless habits of the civil wars, or had even arisen in time of peace. Gangs of grassatores openly went about with swords by their sides, ostensibly to protect themselves, and travellers in the country, freemen and slaves alike, were seized and kept in confinement in the workhouses of the land owners; numerous leagues, too, were formed for the commission of crimes of every kind, assuming the title of some new guild.192

Their activities, if left unchecked, threatened the internal security of the armed Provinces of Caesar, the unarmed Provinces of the People and the homeland as well. Augustus’ solution was to deploy the military and root out the sources of criminal behaviour:

Therefore to put a stop to brigandage, he stationed guards of soldiers wherever it seemed advisable, inspected the workhouses, and disbanded all guilds, except such as were of long standing and formed for legitimate purposes.193

The stated mission of Nero Claudius Drusus’ war in Raetia in 15 BCE was to eradicate bandits freely operating in Gallia Cisalpina and Italy.194 (The offensive in the Alps was explicitly a ‘Just War’.) In 5 BCE, Sulpicius Quirinius fought a hard war against the coalition of bandits called Homonadeis in Cilicia, taking 4,000 prisoners when he had completed his campaign. In the Iberian Peninsula, the measures taken by the robber named Corocotta to evade capture in 26 BCE succeeded in turning this ancient Robin Hood figure into a lovable old rogue who earned the clemency of Augustus and a cash reward. The outcome of this concerted action was to rid the world of brigandage, a fact lauded by Velleius Paterculus as the major achievement of the Pax Augusta.195

Riots threatened the peace of urban life from time to time (table 12). Then, as now, they were a way for the people to express their frustration with authority. In Rome in 21 BCE, Agrippa had to quell disturbances on two different occasions, once when Augustus refused to stand for consul and again over the election of a junior prefect who attended the Latin Festival. More serious, on his outbound journey to the East in the same year Augustus learned of violent clashes in the streets of several cities in Asia. He was informed that Roman citizens had been flogged and summarily executed in Mysia, Anatolia. Augustus’ justice was swift, condemning the inhabitants of Mysia to slavery. Tyre and Sidon also received severe punishments for similar crimes. Following the removal of Archelaos and the annexation of Iudaea into the Province of Caesar in 6 CE, protests against the mandatory census in Hierosolyma rapidly spread to other parts of the country. When these vocal demonstrations became violent acts of sedition, they were suppressed with armed force by Coponius, the new Praefectus Iudaeaorum. Orosius informs us there was also a riot in Athens in 11 CE, a remarkable occurrence so late in Augustus’ reign.196

Table 12. Incidents of Civil Protest and Riot, 31 BCE–14 CE.

| Years | Region/City | Disturbance |

| 28 BCE | Heroöpolis – Egypt | Riot |

| 21 | Rome | Riot |

| 21 | Athens | Peaceful protest |

| 21 | Kyzikos – Mysia | Riot |

| 21 | Tyre – Syria | Riot |

| 21 | Sidon – Syria | Riot |

| 19 | Rome | Riot |

| 20 | Alexandria | Riot |

| 4 | Hierosolyma – Iudaea | Riot |

| 11 CE | Athens | Riot |

Sources: Acts; Dio; Josephus; Orosius.

Augustus as Victor

The term Pax Augusta was rarely used during the lifetime of the princeps and was not a motto he actively promoted.197 It is known only from a few inscriptions erected by private individuals and officials in communities, such as the decuriones of Colonia Praeneste.198 There was an altar to Pax Augusta at Narbo erected by one T. Domitius Romulus (fig. 13) and a colonia of that name in the Iberian Peninsula.199 To prove he was effective at establishing peace, Augustus turned to ancient tradition. He secured votes in the Senate to close the doors of the Temple of Ianus Quirinus, ‘which our ancestors ordered to be closed whenever there was peace, secured by victory, throughout the whole domain of the Roman People on land and sea’.200 His boast was that while ‘before my birth [it] is recorded to have been closed but twice in all since the foundation of the city, the Senate ordered [it] to be closed three times while I was princeps’.201 The first two occasions occurred during his first ten-year period of imperium. The date of the third closing is not known with certainty, but was likely during the third decennium. There was a vote for closure in 13 BCE, but as Roman troops were actually fighting, legally it could not be permitted. Orosius states that it was in 1 BCE and the doors remained shut for twelve years (but had to be opened again on account of the riot in Athens), but it seems a dubious claim as the Roman army was engaged in wars from Germania to Armenia – unless the Senate was willing to stretch the qualification.202 It may be that Augustus simply counted the vote of 13 BCE in his total, even though the doors were kept open. There was no fourth occasion.

Figure 13. T. Domitius Romulus, a Roman citizen from Narbo, set up an altar to Pax Augusta in gratitude. The peace and prosperity of the Provinces of the People depended in part on the success of the army in the securing the Provinces of Caesar.

Commemorating Augustus’ victories across the world were monuments of every type and style. In Epirus and Egypt stood cities dedicated to his victory. The Greek Nikopolis was a major attraction, drawing tourists to see the sights where the famous Battle of Actium had been fought, and touch the bronze beaks of Queen Kleopatra’s captured ships. The Egyptian Nikopolis, with its modern buildings and amenities, threatened to take the trade away from Alexandria, the city founded by a great Macedonian king. Traffic on the road leaving Gallia Narbonnensis bound for Italy, passed a tower of tiered columns and sculptures that marked the end of wars in the Alps. On the Rhine, a similar monument celebrated the life of one of Rome’s youngest and most successful commanders, Nero Claudius Drusus, at which the legions held annual races, while on the left bank of the Elbe, a trophy of decaying armour tied to a tree and rotting shields stacked beneath marked his northeastern-most march. In 9 BCE, the letter and decrees of the proconsul of Asia declared Augustus as ‘the saviour who has brought war to an end’, while the people of Hispania Ulterior Baetica paid for a gold statue dedicated to the princeps in the Forum Augustum, stating as their reason in the inscription beneath ‘because by his beneficence and perpetual care the province has been pacified’.203 There were many more inscriptions and altars paid for by grateful citizens or communities (such as the Concilium Galiarum) dedicated to the man who, they believed, had brought an end to war.

Rome too was decorated with tributes in brick and marble to Augustus’ victories.204 Arriving in Rome in 14 CE by way of the Via Appia, the visitor would pass through the Porta Capena. Close by was the Altar of Fortuna Redux, erected by a grateful nation for the return of Augustus in 19 BCE.205 He would pass under the Arch of Nero Claudius Drusus Imperator, decorated with an equestrian statue of the commander caught in a dramatic attack pose, flanked by trophies of captured Germanic war spoils and bound warriors. On his way towards the city centre, he would pass temples erected by commanders of ages past, now repaired and made grander through Augustus’ generosity. Approaching the Forum Romanum from the southeast along the Via Sacra, the visitor would pass through his arch with three gates, built to commemorate the return of signa and aquilae from Parthia. He would note the inscribed list of all the commanders who had ever been granted triumphs, ending with the name of Cornelius Balbus ex Africa.206 It stood to the right of the Temple of Divus Iulius and the sacred spot before it where his body was burned. In front, the visitor would see the speakers’ platform bearing the rostra of several ships captured at Actium, the arch for which likely stood on the left side. The tiled roofs of many buildings renovated by Augustus were decorated with terminals (antefices) stamped with the emblematic trophy erected after the sea battle. To his left, he would pass the Temple of Castor and Pollux restored by Tiberius and paid for from war spoils. It bore his and his brother’s names on the entablature. (The attentive visitor would note the spelling as ‘Claudianus’ instead of ‘Claudius’ because of his adoption into the family of Augustus.) To retreat from the glare of the sun (or stay out of the rain), he would stroll within the wide two-storey arcade of the Basilica Iulia next door, built by Iulius Caesar from Gallic War spoils, but enlarged and completed by Augustus who renamed it the Basilica of Caius and Lucius.207

Once back in the Forum, he would pass the Temple of Saturn, whose repair was paid for by Munatius Plancus, and in the vaults of which were kept the strong boxes of the Aerarium Saturni and Militare. Upon the Capitolinus Hill, towering above our visitor to Rome, stood the Temple of Iupiter Optimus Maximus (‘Jupiter the Best and Greatest’) and the refurbished Temple of Iupiter Feretrius, where Augustus had placed laurels from his fasces upon his several returns from overseas. Beside it was the small but opulent Temple of Iupiter Tonans (‘Jupiter the Thunderer’), erected in gratitude by Augustus for sparing him injury when a lightning bolt struck during the Cantabrian and Asturian War. At ground level, standing close by on the left, was the Temple of Concord dedicated by Tiberius on behalf of himself and his brother.

On the other side of the Forum, just to the right of his view, was the small Temple of Ianus, whose doors Augustus boasted he had caused to be closed three times. Behind it stood the Curia Iulia, where the Senate met and renewed Augustus’ imperium. Upon its interior walls hung the silver shields of C. and L. Caesar and a statue of flying Victoria with the seats of the two consuls placed in front, and a third sella curulis set in between for Augustus when he attended meetings. Behind it he could still see the high wall enclosing the Forum Augustum. Just visible from here would be the roof of the grand Temple of Mars Ultor, built by Imp. Caesar to fulfill his solemn vow to the god for enabling his victory at the Battle of Phillipi. Supported by massive yet still elegant Corinthian columns, it was second only to the Temple of Iupiter Optimus Maximus in size.208 With time allowing, the visitor could explore it, enjoy the rich marbles of its open and covered spaces, pay his respects to the image of Mars Ultor, gaze up at the giltbronze quadriga driven by Augustus, promenade its arcades lined with statues of the viri triumphatores and read their inspirational biographies – perhaps even catch a glimpse of the famous standards recovered from the Parthian king.

Returning to the Forum Romanum, turning right and sauntering along the Via Flaminia through the wide plain of the Campus Martius, the visitor would pass several buildings whose construction was paid from the proceeds of war booty – the Theatre of Pompeius Magnus (repaired by Augustus), Theatre of Cornelius Balbus, Amphitheatre of Statilius Taurus and a cluster of immense structures created by M. Agrippa. These include the Baths of Neptune, whose walls and ceilings were painted with naval battle scenes, and the Pantheon (which he had originally hoped to dedicate to his friend as the Augusteum). In the far distance he could admire the tree-covered, man-made mound of the Mausoleum of Augustus, in which were stored the ashes of three generations of the Domus Augusti who had borne arms in war – Marcellus, Drusus, Agrippa and the two young Caesars. After a pleasant walk he would reach the Horologium – also known as the Solarium Augusti – with an obelisk transported from Egypt in 30 BCE. It was precisely positioned so that its long shadow moved across a sun dial and reached its greatest extent on 23 September – Augustus’ birthday.209

On that special day, the same shadow touched the adjacent Ara Pacis Augustae. Its exquisitely carved panels, picked out in colour, presented an image of Roman high society (priests, the friends and family of Augustus, with the princeps himself shown as pontifex maximus) processing to a dedication ceremony. Of the Ara Pacis Augustae in Rome, Augustus himself writes in Res Gestae:

When I returned from Hispania and Gallia, in the consulship of Ti. Nero and P. Quinctilius [13 BCE], after successful operations in those provinces, the Senate voted in honour of my return the consecration of an altar to Pax Augusta in the Campus Martius, and on this altar it ordered the magistrates and priests and Vestal virgins to make annual sacrifice.210

A triumph of the sculptor’s craft, many of the allegorical or divine figures on the Ara Pacis defy identification and interpretation today. Scholars have, for example, attempted to name the image of the central figure on the east front, outer face of the left-side segment wall. Venus, Tellus (Mother Earth), Italia and Ceres have variously been suggested, and a case has even been made that this is the avatar of Pax Augusta.211 The argument goes that placed about her are shown many attributes of peace, and other details that strongly suggest this identification. In Greek mythology, the goddess of peace was one of the three Horai (Horae in Latin), divinities who brought justice and prosperity through the seasons of the year. Pax is attended by two goddesses who are also Horae. Allusions in the relief to wind, rain, stars, land and sea present her as a goddess for all seasons.212 The panel on the east front, outer face of the right-side segment wall is generally agreed to show the tutelary warrior goddess Roma. She sits on a pile of arms, armour and shields.213 On the west face, right-side of the outer wall, Aeneas – or alternatively Numa – sacrifices to the Di Penates, while on the left-side, Mars, father of twins Romulus and Remus, is shown.214 The altar and its annual sacrifice were, perhaps, held in connection with the nearby Horologium or Solarium Augusti.215 Mysteries remain about these important imperial structures.

Contemporary poets wrote of life and love, but hardly any, it appears, explicitly used the term Pax Augusta. Yet they sang of victory in all its forms. Vergil set the Battle of Actium to verse, describing how the oars of Imp. Caesar’s and Agrippa’s warships churned up the sea while burning missiles flew through the air.216 Horace composed an ode in celebration of the commander-in-chief’s victory at sea, the capture of Alexandria and the fall of Kleopatra; but in another he congratulated the soldier Plotius Numida upon his return from the war in Cantabria, and praised Augustus as a god on earth for subjugating the Britons and Parthians.217 A poet could often say what a military man or a politician (especially one who was both) could not. After all, it took Vergil to articulate Rome’s manifest destiny in just three words: imperium sine fine.

Nor did Pax Augusta appear on coins while Augustus was alive. Even the name of Pax or her avatar was rarely depicted (see Appendix 4). The Augustan doctrine was about projecting power and military strength (plate 42). Official messaging from the Rome mint – the nearest thing to propaganda in the modern sense – stressed aspects of gloria and victoria. The reverses of coins minted in the period 31–28 BCE showed the naval trophies of the Actian War, the triumphal arch, the god Mars the Avenger and Victory (plate 34). From 27–19 BCE, the trophy from Actium continued to be a motif, but now the honours granted Augustus – the Altar of Fortuna Redux, the corona civica – appeared, as well as a prolific series of different images celebrating the return of the standards from Parthia and the legend SIGNIS RECEPTIS. With the opening of the mints in Hispania Citerior, coins depicted spoils taken in the wars over the Astures and Cantabri, at the same time the mint in Pergamum announced ARMENIA CAPTA. From 18–9 BCE, the tresviri monetales in Rome approved a wide variety of images, including the gods Mars and Victory, the triple triumphal arch commemorating the Parthian Peace, two men holding up laurel branches to Augustus seated on a tribunal, and kneeling barbarians from Germania and Parthia in acts of surrender. The Spanish colonial mints showed Augustus driving a triumphator’s chariot and the embroidered toga picta or a laurel crown. From 8 BCE–2 CE and 3–12 CE, when the new mint at Colonia Copia Felix Munatia – now the source of gold and silver coins – came on stream, Augustus’ adopted sons C. and L. Caesar appeared for the first time as principes iuventutis with their shields and spears. When the older boy went on his first mission, a coin design showed him on a horse galloping past military standards. Despite the premature deaths of the two boys, the coins showing C. and L. Caesar together continued to be minted. Thereafter, the martial imagery largely disappeared from new issues, the series abruptly ending with the image of Tiberius in his triumphal quadriga. The ongoing display of warrelated themes on coins for so many years sustained the notion of military success, but also reminded Romans that they still had battles to win. The final clash of arms still lay ahead but, in the meantime, each victory secured pax.

On the obverse of every gold or silver coin was the bust of the man responsible for bringing victory: CAESAR AVGUSTVS DIVI F. He was not the first living Roman to place his likeness on the coinage (that pioneer was Iulius Caesar), but his heir took the concept to its logical extreme. Unlike his great uncle, whose portraits were brutally realistic, almost caricatures, Augustus’ never betrayed his age.218 His image was timeless. He was never shown with a furrow or wrinkle, and always without emotion. All busts of Augustus in bronze or marble were presented with this same eternally youthful and imperturbable countenance. His head of thick, tousled hair was variously shown bare, graced with a victor’s wreath of laurel or the military distinction of a crown of a twisted leafy oak branch. The Blacas Cameo (plate 41) and the gemma Augustea, which may have been crafted as diplomatic gifts, project iconic depictions of military strength – and that of the Roman leader in particular. This carefully crafted image projected the ideal of the man leading the army to victory in the service of the Roman People, a man who just might defy Nature and live forever – unless he became a god first.

The meaning of the iconic (but enigmatic) statue of Augustus of Prima Porta now becomes clear. 219 The sculpture (perhaps a copy of one in bronze) blends a real occasion with a propaganda message. Augustus is shown frozen at the moment of receiving the acclamation of Roman troops following the recovery of the venerated legionary ensigns from the Parthians in 20 BCE (plate 43). The embossed decoration on his anatomical cuirass depicts the historical event alongside worldly emblems of victory (a trophy and figures from conquered barbarian nations) and mythological associations of a prosperous future; it is intended as a pictorial display to explain the statue to the casual viewer. The paludamentum (which would normally be attached at the shoulders) hangs around his waist as he would have worn it when he had disrobed after battle – this also explains why he carries no weapon. His outstretched right hand and fingers form a gesture used by Roman orators to convey wonder (admiratio), expressing the surprise mingled with admiration he feels at the spontaneous adulation of his fellow citizens.220 The left hand, nowadays presumed to originally have held a sceptre or spear, likely once held a staff topped by an eagle (a copy of one of the rescued aquilae depicted on the cuirass) that he would proudly display to the assembled troops; this same pose was evoked on a later coin (plate 44) celebrating the retrieval by Augustus’ own grandson of the standards Quinctilius Varus lost to the Germans.221 Being careful to avoid appearing god-like, the then 43-year-old military leader is shown walking barefoot like a supplicant, both to indicate his humility and to demonstrate the complete absence of hubris. Amid the cheers of the soldiers Augustus is not only re-affirmed as imperator but as pacificator (the bringer of peace through victory) – specifically a victory made exceptional because he achieved it without bloodshed. It was a defining moment in the emerging legend of the restorer of the Res Publica, the son and avenger of the Divine Iulius, who had defeated a wayward queen and a haughty ‘king of kings’.

Under the auspices of the man who had taken ‘commander’ as his first name, his team of deputies waged war against the People’s enemies far beyond the borders of their realm. For those who could not accept defeat within them – and there were many – the process of pacification was brutal. So long as there was bellum there was the potential for victoria, and with it pax. Almost by design, war was being fought somewhere in virtually every one of the forty-five years that Augustus was commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The dirty little secret was that the mission could never be accomplished. This is how Augustus would retain the imperium. As Tacitus writes, looking back on this period, ‘Peace there was, without a doubt, but a bloody one.’222 An added benefit was that a general engaged in war was less likely than an idle one to turn against his supreme commander. In the event one was tempted, Augustus had the highest-paid soldiers stationed in Italy and kept his Germanic bodyguards close by.

Augustus did not enlarge the empire alone – much as he would like posterity to believe. Over four decades, his deputies operated semi-autonomously and the decisions they made while serving in the field contributed to expanding Rome’s dominion just as much as his did. His privilege was to claim the victories and the glory as his own. It was an arrangement that worked because he deftly channelled the Romans’ cultural trait of competitiveness for recognition and reward, and in doing so ensured their complaisance.

Picking the right men for the job was essential to his success. Every three years he had to appoint new legati Augusti for his regional commands. As frequently he had to pick legates for the twenty-eight legions (twenty-five after 9 CE), as well as the many praefecti who commanded the auxiliary units and Cohortes Voluntariorum (see Appendix 3.6). Additionally, he personally selected from the Ordo Equester the praefectus Aegypti, the praefectus Iudaeorum, the two praefecti Praetorii, the praefectus Urbi, the praefectus Vigilum and each praefectus classis of the several fleets. Every year, he chose which young men would fill the open positions for twentyfive or more tribunes with the broad stripe and 140 or so for legionary tribune with the narrow stripe. Augustus’ skill at personnel selection was extraordinary, to judge by the results they delivered:

For successful operations on land and sea, conducted either by myself or by my legati under my auspices, the Senate on fifty-five occasions decreed that thanks should be rendered to the immortal gods.223

These men together maintained Augustus’ original provincia and augmented it with new territories in Galatia-Pamphylia, Germania (for a generation), Hispania Tarraconensis (formerly Citerior), Iudaea, Moesia, Noricum, Pannonia (by enlarging Illyricum) and Raetia. With the annexation of Egypt, they had helped Augustus nearly double the territory of the ‘imperium of the Roman People’ compared to its extent in 44 BCE.224 It was much more than either Pompeius Magnus or Iulius Caesar had accomplished in their lifetimes (compare maps 1 and 25).

After one of the most destructive civil wars in history, the near constant flow of news of victories over foreign enemies – all won in Augustus’ name – assured the living generations of Romans of their rightful place among the ancestors, and bolstered their belief in the nation’s exceptionalism. As well as restoring its polity, Augustus could claim that he had revived the greatness of the Res Publica as a military power and, as its commander-in-chief, implicitly justify his own primacy.

There were military setbacks, yet Augustus’ organization proved remarkably resilient and was able to survive them. What made it possible were his formidable talents both for leadership and management. As a military leader Augustus: had a sense of personal mission and destiny; took the long view and consistently provided strategic direction; favoured fighting ‘just wars’ (wars of necessity) rather than executing a unified ‘grand strategy’ of imperialist expansion (wars of choice); and was prepared to explore diplomatic solutions over military actions, especially with Parthia. As a manager of war Augustus: established a professional standing army of citizen soldiers, augmented by non-Roman auxiliary troops; organized the means to finance the army’s ongoing expenses; delegated operational and tactical decision making to trusted deputies; selected good candidates for field command positions and actively nurtured new talent to replace them; took a close personal interest in their performance; recognised and rewarded successful leaders for their achievements or acts of bravery; enforced discipline with punishments for offenders; assured the common soldiers of regular pay and a bonus at the end of their service; developed strong personal relationships with Rome’s allies to retain their loyalty; assessed the risk of success or failure (the ‘doctrine of the golden fish hook’), then scaled and resourced his military offensives for victory; communicated his accomplishments with the public and shared the spoils with them; and used political and religious protocols to secure his military power.

Under Augustus’ auspices, the restored Res Publica endured and prospered. For four decades, one man determined the direction and shape of Roman military strategy. It was unprecedented and the achievement was exceptional. When Augustus died, the transition of power from him to his successor was virtually conflict-free. Roman did not fight Roman for the right to command.225 That alone was a victory. The decades of struggle had been worth it. In the end there was peace – the Pax Augusta.