3

DEATH IN ITHACA

“The death is particularly sad inasmuch as neither of the deceased’s relatives was able to be at the boy’s bedside.” —Ithaca Daily News

The first hint of trouble came on January 11, 1903, when a feverish Ithacan sought a doctor’s help. Within days, people all over town collapsed into their beds, too weak to move. Soon more than a dozen patients a day were admitted to the city hospital and to Cornell University’s infirmary.

Doctors initially thought they were dealing with an intestinal flu. On January 21, a local newspaper reported 96 cases of grippe. That was wishful thinking. As the symptoms progressed, it became clear that a disease far more dangerous had come to Ithaca—typhoid fever.

One of the city’s newspapers began publishing the names of the sick and the dead. The first to die was William Spence, age forty-eight, who lost his battle with typhoid on January 23.

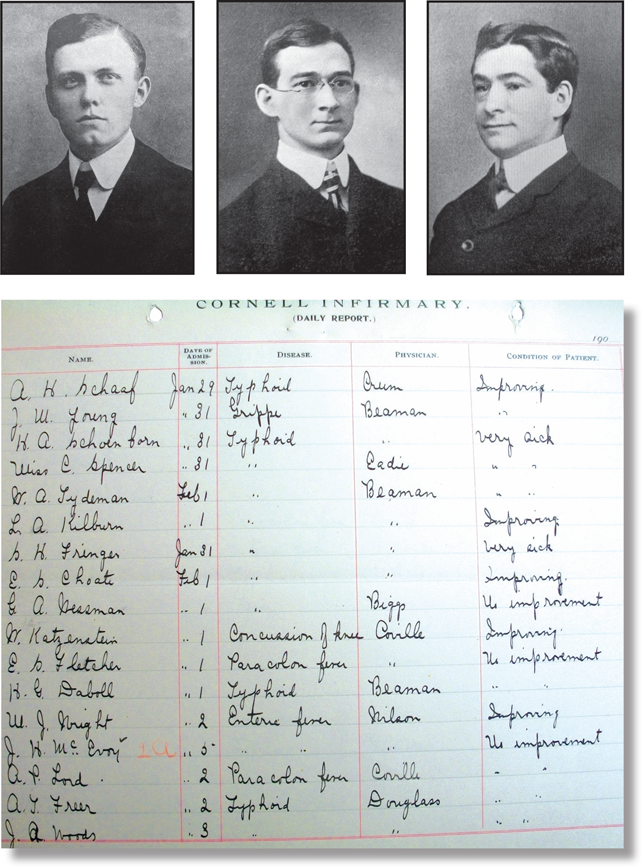

Oliver Shumard was among the Cornell students who fell ill. The son of a Missouri farmer, he had entered the university the previous fall on a scholarship to study philosophy. On January 25, Oliver was admitted to the student infirmary with early symptoms of typhoid.

After three days, he was no better. As other student patients gradually improved, Oliver’s condition worsened, and Cornell officials notified his family. Filled with dread, Oliver’s father immediately boarded a train from Missouri, hoping his son would still be alive when he got to Ithaca.

Just about everyone had a friend or a neighbor or an acquaintance who was suffering with typhoid fever. It seemed as if a black cloud of disease covered the city. Where had it come from? And how could they get rid of it?

POISON WATER

Most of the sick had obtained their drinking water from the private company that supplied the city. Although Ithaca sat on forty-mile-long Cayuga Lake, the water was too polluted to drink. The city sewer system dumped raw human waste into an inlet of the lake. It produced “a scum of undigested sewage material, unsightly and malodorous, drifting with the wind and building up along the shore.”

The company instead pumped the city’s water from two local creeks. The stream water didn’t look as polluted as the lake, but it often had a foul smell and taste. Like many American communities in the early 1900s, the company neither filtered the water to remove feces and other contaminants nor purified it with chemicals to kill bacteria.

Everyone soon realized that the typhoid victims’ drinking water came from the same stream, Six Mile Creek. Two Cornell professors, in bacteriology and in chemistry, tested the creek’s water. They found that it was contaminated with bacteria commonly found in human feces.

Typhoid bacteria were difficult to separate and identify from the other intestinal microbes in the polluted water. But because so many people developed typhoid fever after drinking from the creek, the professors concluded that typhoid bacteria were likely there. The public was drinking “death-dealing impurities.”

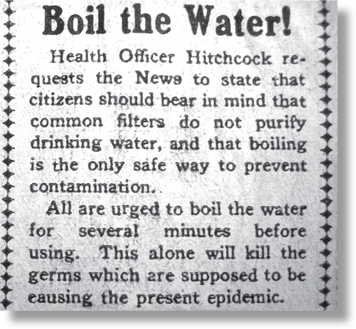

On January 29, more than two weeks after the first cases appeared, the city’s health officer told Ithacans to boil drinking water obtained from the water company. Terrified parents removed faucet handles so that their children couldn’t turn on the water. The school superintendent hired a plumber to cut off city water to all schools, except for flushing toilets.

Cornell University cautioned its students in a written notice: “DO NOT RELAX CARE in regard to water used for brushing the teeth, or taken for any purpose into the mouth. Do not eat uncooked oysters. Do not take any cold drinks nor eat ice cream or uncooked food down town.”

Unfortunately, these actions were too late to prevent the typhoid bacteria from attacking the bodies of those who had already swallowed them. As many as three weeks could pass before an infected person showed symptoms. New cases appeared every day after the boil order was issued.

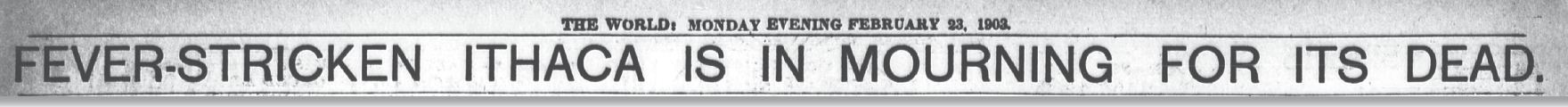

By the beginning of February, more than 340 people had typhoid fever. Ithaca’s three dozen doctors could barely keep up with their house calls. The city hospital was overcrowded. The Cornell infirmary was designed to handle 20 patients, but the nurses there were caring for nearly 60.

To deal with all the sick, the city and university recruited extra nurses from out of town. Cots were set up in a church, in a house near the infirmary, and in the medical-college building on campus.

YOUNG VICTIMS

The outbreak seemed to hit the Cornell students the hardest, a fact that didn’t surprise local doctors. Three years earlier, the federal census revealed that more than a third of typhoid victims were between the ages of fifteen and thirty.

No one was sure why. One hypothesis was that when people left their childhood homes and moved to new places, they were exposed to the bacteria for the first time. Although older Americans developed the disease, too, they did so less often. Perhaps an earlier typhoid bout had protected them.

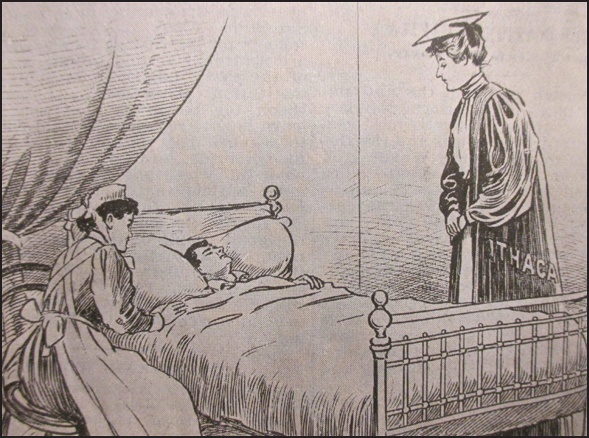

On February 2, Oliver Shumard spent his twenty-sixth birthday in the Cornell infirmary. He was so deathly ill that he was unable to celebrate. Two days later, the infirmary nurses recorded that he was “very sick.” Oliver’s father arrived in Ithaca from Missouri in time to be by his son’s bedside on Friday, February 6. Later that night, Oliver became the first Cornell student to die in the epidemic.

Sophomore Charlotte Spencer of Jasper, New York, was one of about four hundred women studying at Cornell. In 1903, few women had the opportunity to go to college. Charlotte’s parents, who were farmers, were determined to educate all their six children, boys and girls.

When Charlotte was struck down by typhoid fever in late January, she was admitted to the Cornell infirmary. By February 9, the typhoid bacteria had ravaged her body, and the young woman was failing.

“Much concern is felt regarding Miss C. E. Spencer, ’05,” reported an Ithaca newspaper. “She has grown steadily worse within the last 24 hours and the worst is expected.”

Charlotte’s mother rushed from Jasper seventy miles away to be at her side. During the early morning hours of February 10, the typhoid bacteria won out. Charlotte was the first and only female Cornell student to die.

Within a week, 7 fellow students joined Charlotte and Oliver in death. On a single day, February 17, 3 died.

One of them was Henry Schoenborn, a freshman from Hackensack, New Jersey, who had won a scholarship to study law. First in his high-school class, Henry was considered “a student of particular promise.” When he entered the infirmary on January 31, he was already seriously ill. His worried mother traveled from New Jersey to do what she could for her son. But Henry’s intestines began to hemorrhage. Once the bleeding started, nothing could save him.

Henry’s grieving older brother William, a Cornell sophomore in mechanical engineering, quickly left Ithaca to escape the same fate. The next week he wrote Cornell’s president, Jacob Schurman: “Hoping that the conditions at Ithaca may soon improve, so that my parents will permit me to return again to Cornell, I remain still a Cornellian.”

CITY OF FEAR

The community was overwhelmed with sick and dying people. Local doctors sent home about 200 Cornell students when they first showed symptoms, believing the patients would receive better nursing in their hometowns.

Hundreds of other students, afraid that they might be next, also left town, even though they wouldn’t get credit for the classes they missed.

That didn’t guarantee they would escape typhoid’s death sentence. In late January, twenty-two-year-old agriculture student Charles Langworthy and his roommate, Edward Green, developed signs of typhoid. Their Ithaca doctor recommended that both young men take the one-hundred-mile train trip to their hometown of Alfred, New York. Glad to have them home, their families cared for them. But three weeks later, the typhoid bacteria attacked Charles’s intestines, and he bled to death. Edward eventually recovered.

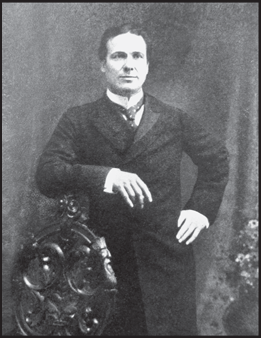

As the epidemic spread, newspapers across the country picked up the story and ran headlines about the “Scourge of Typhoid in Ithaca.” Anxious parents of the students still at school sent frantic telegrams to President Schurman, asking whether their children were safe. He assured them that the university was providing clean water and instructions on avoiding infection.

Despite this, students continued to fall ill. Schurman received a daily update from the infirmary about each of its patients, and he telegraphed the report to parents. When the prognosis looked grim, he advised them to come to their child’s bedside.

Some parents were angry that their children had been infected. One father, whose sophomore son returned home to New Jersey to recover, wrote: “I cannot but feel that the City authorities of Ithaca have been grossly negligent and careless regarding the water supply of the City, and I cannot escape from the feeling that the College authorities have not been blameless.”

The suffering and death would not stop. By Monday of the final week in February, 14 Cornell students and 16 townspeople had tragically succumbed. The dead included five-year-old Esther Howell, daughter of a city council member, and eleven-year-old Catherine Caveney, who lived a few blocks away from little Esther.

A New York City newspaper captured the town’s emotions in a page-wide headline: “Fever-Stricken Ithaca Is In Mourning For Its Dead.”