As the nineteenth century approached its end, mathematicians began to develop a new kind of geometry, one in which familiar concepts such as lengths and angles played no role whatsoever and no distinction was made between triangles, squares, and circles. Initially it was called analysis situs, the analysis of position, but mathematicians quickly settled on another name: topology.

Topology has its roots in a curious numerical pattern that Descartes noticed in 1639 when thinking about Euclid’s five regular solids. Descartes was a French-born polymath who spent most of his life in the Dutch Republic, present-day Netherlands. His fame mainly rests on his philosophy, which proved so influential that for a long time Western philosophy consisted largely of responses to Descartes. Not always in agreement, you appreciate, but motivated by his arguments nonetheless. His sound bite cogito ergo sum – ‘I think, therefore I am’ – has become common cultural currency. But Descartes’s interests extended beyond philosophy into science and mathematics.

In 1639 Descartes turned his attention to the regular solids, and this was when he noticed his curious numerical pattern. A cube has 6 faces, 12 edges, and 8 vertices; the sum 6–12+8 equals 2. A dodecahedron has 12 faces, 30 edges, and 20 vertices; the sum 12–30+20=2. An icosahedron has 20 faces, 30 edges, and 12 vertices; the sum 20–30+12=2. The same relationship holds for the tetrahedron and octahedron. In fact, it applies to a solid of any shape, regular or not. If the solid has F faces, E edges, and V vertices, then F–E+V =2. Descartes viewed this formula as a minor curiosity and did not publish it. Only much later did mathematicians see this simple little equation as one of the first tentative steps towards the great success story in twentieth-century mathematics, the inexorable rise of topology. In the nineteenth century, the three pillars of pure mathematics were algebra, analysis, and geometry. By the end of the twentieth, they were algebra, analysis, and topology.

Topology is often characterised as ‘rubber-sheet geometry’ because it is the kind of geometry that would be appropriate for figures drawn on a sheet of elastic, so that lines can bend, shrink, or stretch, and circles can be squashed so that they turn into triangles or squares. All that matters is continuity: you are not allowed to rip the sheet apart. It may seem remarkable that anything so weird could have any importance, but continuity is a basic aspect of the natural world and a fundamental feature of mathematics. Today we mostly use topology indirectly, as one mathematical technique among many. You don’t find anything obviously topological in your kitchen. However, a Japanese company did market a chaotic dishwasher, which according to their marketing people cleaned dishes more efficiently, and our understanding of chaos rests on topology. So do some important aspects of quantum field theory and that iconic molecule DNA. But, when Descartes counted the most obvious features of the regular solids and noticed that they were not independent, all this was far in the future.

It was left to the indefatigable Euler, the most prolific mathematician in history, to prove and publish this relationship, which he did in 1750 and 1751. I’ll sketch a modern version. The expression F–E+V may seem fairly arbitrary, but it has a very interesting structure. Faces (F) are polygons, of dimension 2, edges (E) are lines, so have dimension 1, and vertices (V) are points, of dimension 0. The signs in the expression alternate, +–+, with + being assigned to features of even dimension and – to those of odd dimension. This implies that you can simplify a solid by merging its faces or removing edges and vertices, and these changes will not alter the number F–E+V provided that every time you get rid of a face you also remove an edge, or every time you get rid of a vertex you also remove an edge. The alternating signs mean that changes of this kind cancel out.

Now I’ll explain how this clever structure makes the proof work. Figure 21 shows the key stages. Take your solid. Deform it into a nice round sphere, with its edges being curves on that sphere. If two faces meet along a common edge, then you can remove that edge and merge the faces into one. Since this merger reduces both F and E by 1, it doesn’t change F–E+V. Keep doing this until you get down to a single face, which covers almost all of the sphere. Aside from this face, you are left with only edges and vertices. These must form a tree, a network with no closed loops, because any closed loop on a sphere separates at least two faces: one inside it, the other outside it. The branches of this tree are the remaining edges of the solid, and they join together at the remaining vertices. At this stage only one face remains: the entire sphere, minus the tree. Some branches of this tree connect to other branches at both ends, but some, at the extremes, terminate in a vertex, to which no other branches attach. If you remove one of these terminating branches together with that vertex, then the tree gets smaller, but since both E and V decrease by 1, F–E+V again remains unchanged.

This process continues until you are left with a single vertex sitting on an otherwise featureless sphere. Now V=1, E=0, and F=1. So F–E+V = 1–0 + 1 = 2. But since each step leaves F–E+V unchanged, its value at the beginning must also have been 2, which is what we want to prove.

Fig 21 Key stages in simplifying a solid. Left to right: (1) Start. (2) Merging adjacent faces. (3) Tree that remains when all faces have been merged. (4) Removing an edge and a vertex from the tree. (5) End.

It’s a cunning idea, and it contains the germ of a far-reaching principle. The proof has two ingredients. One is a simplification process: remove either a face and an adjacent edge or a vertex and an edge that meets it. The other is an invariant, a mathematical expression that remains unchanged whenever you carry out a step in the simplification process. Whenever these two ingredients coexist, you can compute the value of the invariant for any initial object by simplifying it as far as you can, and then computing the value of the invariant for this simplified version. Because it is an invariant, the two values must be equal. Because the end result is simple, the invariant is easy to calculate.

Now I have to admit that I’ve been keeping one technical issue up my sleeve. Descartes’s formula does not, in fact, apply to any solid. The most familiar solid for which it fails is a picture frame. Think of a picture frame made from four lengths of wood, each rectangular in cross-section, joined at the four corners by 45° mitres as in Figure 22 (left). Each length of wood contributes 4 faces, so F=16. Each length also contributes 4 edges, but the mitre joint creates 4 more at each corner, so E= 32. Each corner comprises 4 vertices, so V = 16. Therefore F − E + V = 0.

What went wrong?

Fig 22 Left: A picture frame with F − E + V = 0. Right: Final configuration when the picture frame is smoothed and then simplified.

There’s no problem with F–E+V being invariant. Neither is there much of a problem with the simplification process. But if you work through it for the frame, always cancelling one face against one edge, or one vertex against one edge, then the final simplified configuration is not a single vertex sitting in a single face. Performing the cancellation in the most obvious way, what you get is Figure 22 (right), with F = 1, V = 1, E = 2. I’ve smoothed the faces and edges for reasons that will quickly become apparent. At this stage removing an edge just merges the sole remaining face with itself, so the changes to the numbers no longer cancel. This is why we stop, but we’re home and dry anyway: for this configuration, F − E + V = 0. So the method performs perfectly. It just yields a different result for the picture frame. There must be some fundamental difference between a picture frame and a cube, and the invariant F − E + V is picking it up.

The difference turns out to be a topological one. Early in my version of Euler’s proof, I told you to take the solid and ‘deform it into a nice round sphere’. But this is not possible for the picture frame. It’s not shaped like a sphere, even after being simplified. It is a torus, which looks like an inflatable rubber ring with a hole through the middle. The hole is also clearly visible in the original shape: it’s where the picture would go. A sphere, in contrast, has no holes. The hole in the frame is why the simplification process leads to a different result. However, we can wrest victory from the jaws of defeat, because F − E + V is still an invariant. So the proof tells us that any solid that is deformable into a torus will satisfy the slightly different equation F − E + V = 0. In consequence, we have the basis of a rigorous proof that a torus cannot be deformed into a sphere: that is, the two surfaces are topologically different.

Of course this is intuitively obvious, but now we can support intuition with logic. Just as Euclid started from obvious properties of points and lines, and formalised them into a rigorous theory of geometry, the mathematicians of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries could now develop a rigorous formal theory of topology.

Fig 23 Left: 2-holed torus. Right: 3-holed torus.

Where to start was a no-brainer. There exist solids like a torus but with two or more holes, as in Figure 23, and the same invariant should tell us something useful about those. It turns out that any solid deformable into a 2-holed torus satisfies F − E + V = −2, any solid deformable into a 3-holed torus satisfies F − E + V = −4, and in general any solid deformable into a g-holed torus satisfies F − E + V = 2−2g. The symbol g is short for ‘genus’, the technical name for ‘number of holes’. Pursuing the line of thought that Descartes and Euler began leads to a connection between a quantitative property of solids, the number of faces, vertices, and edges, and a qualitative property, possessing holes. We call F − E + V the Euler characteristic of the solid, and observe that it depends only on which solid we are considering and not on how we cut it into faces, edges, and vertices. This makes it an intrinsic feature of the solid itself.

Agreed, we count the number of holes, a quantitative operation, but ‘hole’ itself is qualitative in the sense that it’s not obviously a feature of the solid at all. Intuitively, it’s a region in space where the solid isn’t. But not any such region. After all, that description applies to all of the space surrounding the solid, and no one would consider it all to be a hole. And it also applies to all of the space surrounding a sphere . . . which doesn’t have a hole. In fact, the more you start to think about what a hole is, the more you realise that it’s quite tricky to define one. My favourite example to show just how confusing it all gets is the shape in Figure 24, known as a hole-through-a-hole-in-a-hole. Apparently you can thread a hole through another hole, which is actually a hole in a third hole.

This way lies madness.

It wouldn’t much matter if solids with holes in them never turned up anywhere important. But by the end of the nineteenth century they were turning up all over mathematics – in complex analysis, algebraic geometry, and Riemann’s differential geometry. Worse, higher-dimensional analogues of solids were taking centre stage, in all areas of pure and applied mathematics; as already noted, the dynamics of the Solar System requires 6 dimensions per body. And they had higher-dimensional analogues of holes. Somehow it was necessary to bring a modicum of order into the area. And the answer turned out to be . . . invariants.

Fig 24 Hole-through-a-hole-in-a-hole.

The idea of a topological invariant goes back to Gauss’s work on magnetism. He was interested in how magnetic and electrical field lines could link with each other, and he defined the linking number, which counts how many times one field line winds round another. This is a topological invariant: it remains the same if the curves are continuously deformed. He found a formula for this number using integral calculus, and every so often he expressed a wish for a better understanding of the ‘basic geometric properties’ of diagrams. It is no coincidence that the first serious inroads into such an understanding came through the work of one of Gauss’s students, Johann Listing, and Gauss’s assistant August Möbius. Listing’s Vorstudien zur Topologie (‘Studies in Topology’) of 1847 introduced the word ‘topology’, and Möbius made the role of continuous transformations explicit.

Listing had a bright idea: seek generalisations of Euler’s formula. The expression F − E + V is a combinatorial invariant: a feature of a specific way of describing a solid, based on cutting it into faces, edges, and vertices. The number g of holes is a topological invariant: something that does not change however the solid is deformed, as long as the deformation is continuous. A topological invariant captures a qualitative conceptual feature of a shape; a combinatorial one provides a method for calculating it. The two together are very powerful, because we can use the conceptual invariant to think about shapes, and the combinatorial version to pin down what we are talking about.

In fact, the formula lets us sidestep the tricky issue of defining ‘hole’ altogether. Instead, we define ‘number of holes’ as a package, without either defining a hole or counting how many there are. How? Easy. Just rewrite the generalised version of Euler’s formula F − E + V = 2 −2g in the form

g = 1 – F/2 + E/2 – V/2

Now we can calculate g by drawing faces and so forth on our solid, counting F, E, and V, and substituting those values into the formula. Since the expression is an invariant, it doesn’t matter how we cut the solid up: we always get the same answer. But nothing that we do depends on having a definition of a hole. Instead, ‘number of holes’ becomes an interpretation, in intuitive terms, derived by looking at simple examples where we feel we know what the phrase should mean.

It may seem like a cheat, but it makes significant inroads into a central question in topology: when can one shape be continuously deformed into another? That is, as far as topologists are concerned, are the two shapes the same or not? If they are the same, their invariants must also be the same; conversely, if the invariants are different, so are the shapes. (However, sometimes two shapes might have the same invariant, but be different; it depends on the invariant.) Since a sphere has Euler characteristic 2, but a torus has Euler characteristic 0, there is no way to deform a sphere continuously into a torus. This may seem obvious, because of the hole. . . but we’ve seen the turbulent waters into which that way of thinking can lead. You don’t have to interpret the Euler characteristic in order to use it to distinguish shapes, and here it is decisive.

Less obviously, the Euler characteristic shows that the puzzling hole-through-a-hole-in-a-hole (Figure 24) is actually just a 3-holed torus in disguise. Most of the apparent complexity stems not from the intrinsic topology of the surface, but from the way I have chosen to embed it in space.

The first really significant theorem in topology grew out of the formula for the Euler characteristic. It was a complete classification of surfaces, curved two-dimensional shapes like the surface of a sphere or that of a torus. A couple of technical conditions were also imposed: the surface should have no boundary, and it should be of finite extent (the jargon is ‘compact’).

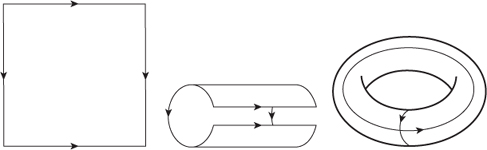

For this purpose a surface is described intrinsically; that is, it is not conceived as existing in some surrounding space. One way to do this is to view the surface as a number of polygonal regions (which topologically are equivalent to circular discs) that are glued together along their edges according to specified rules, like the ‘glue tab A to tab B’ instructions you get when assembling a cardboard cut-out. A sphere, for instance, can be described using two discs, glued together along their boundaries. One disc becomes the northern hemisphere, the other the southern hemisphere. A torus has an especially elegant description as a square with opposite edges glued to each other. This construction can be visualised in a surrounding space (Figure 25), which explains why it creates a torus, but the mathematics can be carried out using just the square together with the gluing rules, and this offers advantages precisely because it is intrinsic.

Fig 25 Gluing the edges of a square to make a torus.

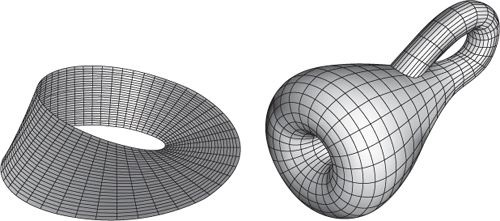

The possibility of gluing bits of boundary together leads to a rather strange phenomenon: surfaces with only one side. The most famous example is the Möbius band, introduced by Möbius and Listing in 1858, which is a rectangular strip whose ends are glued together with a 180° turn (usually called a half-twist, on the convention that 360° constitutes a full twist). The Möbius band, see Figure 26 (left), has an edge, comprising the edges of the rectangle that don’t get glued to anything. This is the only edge, because the two separate edges of the rectangle are connected together into a closed loop by the half-twist, which glues them end to end.

It is possible to make a model of a Möbius band from paper, because it embeds naturally in three-dimensional space. The band has only one side, in the sense that if you start painting one of its surfaces, and keep going, you will eventually cover the entire surface, front and back. This happens because the half-twist connects the front to the back. That’s not an intrinsic description, because it relies on embedding the band in space, but there is an equivalent, more technical property known as orientability, which is intrinsic.

Fig 26 Left: Möbius band. Right: Klein bottle. The apparent self-intersection occurs because the drawing embeds it in three-dimensional space.

There is a related surface with only one side, having no edges at all, Figure 26 (right). It arises if we glue two sides of a rectangle together like a Möbius band, and glue the other two sides together without any twisting. Any model in three-dimensional space has to pass through itself, even though from an intrinsic point of view the gluing rules do not introduce any self-intersections. If this surface is pictured with such a crossing, it looks like a bottle whose neck has been poked through the side wall and joined to the bottom. It was invented by Felix Klein, and is known as a Klein bottle – almost certainly a joke based on a German pun, changing Kleinsche Fläche (Klein’s surface) to Kleinsche Flasche (Klein’s bottle).

The Klein bottle has no boundary and is compact, so any classification of surfaces must include it. It is the best known of an entire family of onesided surfaces, and surprisingly it is not the simplest. This honour goes to the projective plane, which arises if you glue both pairs of opposite sides of a square together, with a half-twist for each. (This is difficult to do with paper because paper is too rigid; like the Klein bottle it requires the surface to intersect itself. It is best done ‘conceptually’, that is, by drawing pictures on the square but remembering the gluing rules when lines go off the edge and ‘wrap round’.) The classification theorem for surfaces, proved by Johann Listing around 1860, leads to two families of surfaces. Those with two sides are the sphere, torus, 2-holed torus, 3-holed torus, and so on. Those with only one side form a similar infinite family, starting with the projective plane and the Klein bottle. They can be obtained by cutting a small disc out of the corresponding two-sided surface and gluing in a Möbius band instead.

Surfaces turn up naturally in many areas of mathematics. They are important in complex analysis, where surfaces are associated with singularities, points at which functions behave strangely – for instance, the derivative fails to exist. Singularities are the key to many problems in complex analysis; in a sense they capture the essence of the function. Since singularities are associated with surfaces, the topology of surfaces provides an important technique for complex analysis. Historically, this motivated the classification.

Most modern topology is highly abstract, and a lot of it happens in four or more dimensions. We can get a feel for the subject in a more familiar setting: knots. In the real world, a knot is a tangle tied in a length of string. Topologists need a way to stop the knot escaping off the ends once it has been tied, so they join the ends of the string together to form a closed loop. Now a knot is just a circle embedded in space. Intrinsically, a knot is topologically identical to a circle, but on this occasion what counts is how the circle sits inside its surrounding space. This might seem contrary to the spirit of topology, but the essence of a knot lies in the relation between the loop of string and the space that surrounds it. By considering not just the loop, but how it relates to space, topology can tackle important questions about knots. Among these are:

•How do we know a knot is really knotted?

•How can we distinguish topologically different knots?

•Can we classify all possible knots?

Experience tells us that there are many different types of knot. Figure 27 shows a few of them: the overhand or trefoil knot, reef knot, granny knot, figure-8, stevedore’s knot, and so on. There is also the unknot, an ordinary circular loop; as the name reflects, this loop is not knotted. Many different kinds of knot have been used by generations of mariners, mountaineers, and boy scouts. Any topological theory should of course reflect this wealth of experience, but everything has to be proved, rigorously, within the formal setting of topology, just as Euclid had to prove Pythagoras’s theorem instead of just drawing a few triangles and measuring them. Remarkably, the first topological proof that knots exist, in the sense that there is an embedding of the circle that cannot be deformed into the unknot, first appeared in 1926 in the German mathematician Kurt Reidemeister’s Knoten und Gruppen (‘Knots and Groups’). The word ‘group’ is a technical term in abstract algebra, which quickly became the most effective source of topological invariants. In 1927 Reidemeister, and independently the American James Waddell Alexander, in collaboration with his student G. B. Briggs, found a simpler proof of the existence of knots using the ‘knot diagram’. This is a cartoon image of the knot, drawn with tiny breaks in the loop to show how the separate strands overlap, as in Figure 27. The breaks are not present in the knotted loop itself, but they represent its three-dimensional structure in a two-dimensional diagram. Now we can use the breaks to split the knot diagram into a number of distinct pieces, its components, and then we can manipulate the diagram and see what happens to the components.

Fig 27 Five knots and the unknot.

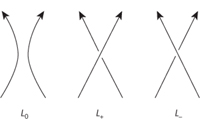

If you look back at how I used the invariance of the Euler characteristic, you’ll see that I simplified the solid using a series of special moves: merge two faces by removing an edge, merge two edges by removing a point. The same trick applies to knot diagrams, but now you need three types of move to simplify them, called Reidemeister moves, Figure 28. Each move can be carried out in either direction: add or remove a twist, overlap two strands or pull them apart, move one strand through the place where two others cross.

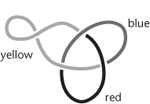

With some preliminary fiddling to tidy up the knot diagram, such as modifying places where three curves overlap if that ever happens, it can be proved that any deformation of a knot can be represented as a finite series of Reidemeister moves applied to its diagram. Now we can play the Euler game; all we have to do is find an invariant. Among them is the knot group, but there is a far simpler invariant that proves the trefoil really is a knot. I can explain it in terms of colouring the separate components in a knot diagram. I’m starting with a slightly more complicated diagram than I have to, with an extra loop, in order to illustrate some features of the idea, Figure 29.

Fig 29 Colouring a trefoil knot with an extra twist.

The extra twist creates four separate components. Suppose I colour the components using three colours for each, say red, yellow, and blue (shown in the figure as black, light grey, and dark grey). Then this colouring obeys two simple rules:

•At least two distinct colours are used. (Actually all three are, but that’s extra information that I don’t need.)

•At each crossing, either the three strands near the crossing all have different colours or they are all the same colour. Near the crossing caused by my extra loop, all three components are yellow. Two of these components (in yellow) join up elsewhere, but near the crossing they are separate.

The wonderful observation is that if a knot diagram can be coloured using three colours, obeying these two rules, then the same is true after any Reidemeister move. You can prove this very easily by working out how the Reidemeister moves affect the colours. For example, if I untwist the extra loop in my picture then I can leave the colours unchanged and everything still works. Why is this wonderful? Because it proves that the trefoil really is knotted. Suppose for the sake of argument that it can be unknotted; then some series of Reidemeister moves turns it into an unknotted loop. Since the trefoil can be coloured to obey the two rules, the same must apply to the unknotted loop. But an unknotted loop consists of a single strand with no overlaps, so the only way to colour it is to use the same colour everywhere. But this violates the first rule. By contradiction, no such series of Reidemeister moves can exist; that is, the trefoil can’t be unknotted.

This proves that the trefoil is knotted, but doesn’t distinguish it from other knots such as the reef knot or the stevedore’s knot. One of the earliest effective ways to do this was invented by Alexander. It was derived from Reidemeister’s abstract algebra methods, but it leads to an invariant that is algebraic in the more familiar sense of school algebra. It’s called the Alexander polynomial, and it associates to any knot a formula formed from powers of a variable x. Strictly speaking, the term ‘polynomial’ applies only when the powers are positive integers, but here we also allow negative powers. Table 2 lists a few Alexander polynomials. If two knots in the list have different Alexander polynomials, and here all but the reef and granny do, then the knots must be topologically different. The converse is not true: the reef and granny have the same Alexander polynomials, but in 1952 Ralph Fox proved that they are topologically different. The proof required surprisingly sophisticated topology. It was far more difficult than anyone expected.

knot |

Alexander polynomial |

Unknot |

1 |

Trefoil |

x − 1 + x−1 |

Figure-8 |

− x + 3 − x−1 |

Reef |

x2 −2x + 3 − 2x−1 + x−2 |

Granny |

x2 −2x + 3 −2x−1 + x−2 |

Stevedore’s knot |

− 2x + 5 − 2x−l |

Table 2 Alexander polynomials of knots.

After about 1960 knot theory entered the topological doldrums, becalmed in a vast ocean of unsolved questions, awaiting a breath of creative insight. It came in 1984, when the New Zealand mathematician Vaughan Jones had an idea so simple that it could have occurred to anyone from Reidemeister onwards. Jones wasn’t a knot theorist; he wasn’t even a topologist. He was an analyst, working on operator algebras, an area with strong links to mathematical physics. It wasn’t a total surprise that the ideas applied to knots, because mathematicians and physicists already knew of interesting connections between operator algebras and braids, which are a special kind of multi-stranded knot. The new knot invariant he invented, called the Jones polynomial, is also defined using the knot diagram and three types of move. However, the moves do not preserve the topological type of the knot; they do not preserve the new ‘Jones polynomial’. Amazingly, however, the idea can still be made to work, and the Jones polynomial is a knot invariant.

For this invariant we have to choose a specific direction along the knot, shown by an arrow. The Jones polynomial V(x) is defined to be one for the unknot. Given any knot L0, move two separate strands close together without changing any crossings in its diagram. Be careful to align the directions as shown: that’s why the arrow is needed, and the process doesn’t work without it. Replace that region of L0 by two strands that cross in the two possible ways (Figure 30). Let the resulting knot diagrams be L+and L−. Now define

(x1/2 − x−1/2)V(L0) = x−1V(L+) − x V(L−)

By starting with the unknot and applying such moves in the right way, you can work out the Jones polynomial for any knot. Mysteriously, it turns out to be a topological invariant. And it outperforms the traditional Alexander polynomial; for instance, it can distinguish reef from granny, because they have different Jones polynomials.

Jones’s discovery won him the Fields medal, the most prestigious prize in mathematics. It also triggered an outburst of new knot invariants. In 1985 four different groups of mathematicians, eight people in total, simultaneously discovered the same generalisation of the Jones polynomial and submitted their papers independently to the same journal. All four proofs were different, and the editor persuaded the eight authors to join forces and publish one combined article. Their invariant is often called the HOMFLY polynomial, based on their initials. But even the Jones and HOMFLY polynomials have not fully answered the three problems of knot theory. It is not known whether a knot with Jones polynomial 1 must be unknotted, though many topologists think this is probably true. There exist topologically distinct knots with the same Jones polynomial; the simplest examples known have ten crossings in their knot diagrams. A systematic classification of all possible knots remains a mathematician’s pipedream.

It’s pretty, but is it useful? Topology has many uses, but they are usually indirect. Topological principles provide insight into other, more directly applicable, areas. For instance, our understanding of chaos is founded on topological properties of dynamical systems, such as the bizarre behaviour that Poincaré noted when he rewrote his prizewinning memoir (Chapter 4). The Interplanetary Superhighway is a topological feature of the dynamics of the Solar System.

More esoteric applications of topology arise at the frontiers of fundamental physics. Here the main consumers of topology are quantum field theorists, because the theory of superstrings, the hoped-for unification of quantum mechanics and relativity, is based on topology. Here analogues of the Jones polynomial in knot theory arise in the context of Feynman diagrams, which show how quantum particles such as electrons and photons move through space-time, colliding, merging, and breaking apart. A Feynman diagram is a bit like a knot diagram, and Jones’s ideas can be extended to this context.

To me one of the most fascinating applications of topology is its growing use in biology, helping us to understand the workings of the molecule of life, DNA. Topology turns up because DNA is a double helix, like two spiral staircases winding around each other. The two strands are intricately intertwined, and important biological processes, in particular the way a cell copies its DNA when it divides, have to take account of this complex topology. When Francis Crick and James Watson published their work on the molecular structure of DNA in 1953 they ended with a brief allusion to a possible copying mechanism, presumably involved in cell division, in which the two strands were pulled apart and each was used as the template for a new copy. They were reluctant to claim too much, because they were aware that there are topological obstacles to pulling apart intertwined strands. Being too specific about their proposal might have muddied the waters at such an early stage.

As things turned out, Crick and Watson were right. The topological obstacles are real, but evolution has provided methods for overcoming them, such as special enzymes that cut-and-paste strands of DNA. It is no coincidence that one of these is called topoisomerase. In the 1990s mathematicians and molecular biologists used topology to analyse the twists and turns of DNA, and to study how it works in the cell, where the usual method of X-ray diffraction can’t be used because it requires the DNA to be in crystalline form.

Fig 31 Loop of DNA forming a trefoil knot.

Some enzymes, called recombinases, cut the two DNA strands and rejoin them in a different way. To determine how such an enzyme acts when it is in a cell, biologists apply the enzyme to a closed loop of DNA. Then they observe the shape of the modified loop using an electron microscope. If the enzyme joins distinct strands together, the image is a knot, Figure 31. If the enzyme keeps the strands separate, the image shows two linked loops. Methods from knot theory, such as the Jones polynomial and another theory known as ‘tangles’, make it possible to work out which knots and links occur, and this provides detailed information about what the enzyme does. They also make new predictions that have been verified experimentally, giving some confidence that the mechanism indicated by the topological calculations is correct.1

One the whole, you won’t run into topology in everyday life, aside from that dishwasher I mentioned at the start of this chapter. But behind the scenes, topology informs the whole of mainstream mathematics, enabling the development of other techniques with more obvious practical uses. This is why mathematicians consider topology to be of vast importance, while the rest of the world has hardly heard of it.