Since the turn of the century the greatest source of growth in the financial sector has been in financial instruments known as derivatives. Derivatives are not money, nor are they investments in stocks and shares. They are investments in investments, promises about promises. Derivatives traders use virtual money, numbers in a computer. They borrow it from investors who have probably borrowed it from somewhere else. Often they haven’t borrowed it at all, not even virtually: they have clicked a mouse to agree that they will borrow the money if it ever becomes necessary. But they have no intention of letting it become necessary; they will sell the derivative before that happens. The lender – hypothetical lender, since the loan will never occur, for the same reason – probably doesn’t actually have the money either. This is finance in cloud cuckoo land, yet it has become the standard practice of the world’s banking system.

Unfortunately, the consequences of derivatives trading do, ultimately, turn into real money, and real people suffer. The trick works, most of the time, because the disconnect with reality has no notable effect, other than making a few bankers and traders extremely rich as they siphon off real money from the virtual pool. Until things go wrong. Then the pigeons come home to roost, bearing with them virtual debts that have to be paid with real money. By everyone else, naturally.

This is what triggered the banking crisis of 2008-9, from which the world’s economies are still reeling. Low interest rates and enormous personal bonus payments encouraged bankers and their banks to bet ever larger sums of virtual money on ever more complex derivatives, ultimately secured – so they believed – in the property market, houses and businesses. As the supply of suitable property and people to buy it began to dry up, the financial world’s leaders needed to find new ways to convince shareholders that they were creating profit, in order to justify and finance their bonuses. So they started trading packages of debt, also allegedly secured, somewhere down the line, on real property. Keeping the scheme going demanded the continued purchase of property, to increase the pool of collateral. So the banks started selling mortgages to people whose ability to repay them was increasingly doubtful. This was the subprime mortgage market, ‘subprime’ being a euphemism for ‘likely to default’. Which soon became ‘certain to default’.

The banks behaved like one of those cartoon characters who wanders off the edge of a cliff, hovers in space until he looks down, and only then plunges to the ground. It all seemed to be going nicely until the bankers asked themselves whether multiple accounting with non-existent money and overvalued assets was sustainable, wondered what the real value of their holdings in derivatives was, and realised that they didn’t have a clue. Except that it was definitely a lot less than they’d told shareholders and government regulators.

As the dreadful truth dawned, confidence plummeted. This depressed the housing market, so the assets against which the debts were secured started to lose their value. At this point the whole system became trapped in a positive feedback loop, in which each downward revision of value caused it to be revised even further downward. The end result was the loss of about 17 trillion dollars. Faced with the prospect of the total collapse of the world financial system, trashing depositors’ savings and making the Great Depression of 1929 look like a garden party, governments were forced to bail out the banks, which were on the verge of bankruptcy. One, Lehman Brothers, was allowed to go under, but the loss of confidence was so great that it seemed unwise to repeat the lesson. So taxpayers stumped up the money, and a lot of it was real money. The banks grabbed the cash with both hands, and then tried to pretend that the catastrophe hadn’t been their fault. They blamed government regulators, despite having campaigned against regulation: an interesting case of ‘It’s your fault: you let us do it.’

How did the biggest financial train wreck in human history come about?

Arguably, one contributor was a mathematical equation.

The simplest derivatives have been around for a long time. They are known as futures and options, and they go back to the eighteenth century at the Dojima rice exchange in Osaka, Japan. The exchange was founded in 1697, a time of great economic prosperity in Japan, when the upper classes, the samurai, were paid in rice, not money. Naturally there emerged a class of ricebrokers who traded rice as though it were money. As the Osaka merchants strengthened their grip on rice, the country’s staple food, their activities had a knock-on effect on the commodity’s price. At the same time, the financial system was beginning to shift to hard cash, and the combination proved deadly. In 1730 the price of rice dropped through the floor.

Ironically, the trigger was poor harvests. The samurai, still wedded to payment in rice, but watchful of the growth of money, started to panic. Their favoured ‘currency’ was rapidly losing its value. Merchants exacerbated the problem by artificially keeping rice out of the market, squirrelling away huge quantities in warehouses. Although it might seem that this would increase the monetary price of rice, it had the opposite effect, because the samurai were treating rice as a currency. They could not eat anything remotely approaching the amount of rice they owned. So while ordinary people starved, the merchants stockpiled rice. Rice became so scarce that paper money took over, and it quickly became more desirable than rice because it was possible actually to lay hands on it. Soon the Dojima merchants were running what amounted to a gigantic banking system, holding accounts for the wealthy and determining the exchange rate between rice and paper money.

Eventually the government realised that this arrangement handed far too much power to the rice merchants, and reorganised the Rice Exchange along with most other parts of the country’s economy. In 1939 the Rice Exchange was replaced by the Government Rice Agency. But while the Rice Exchange existed, the merchants invented a new kind of contract to even out the large swings in the price of rice. The signatories guaranteed to buy (or sell) a specified quantity of rice at a specified future date for a specified price. Today these instruments are known as futures or options. Suppose a merchant agrees to buy rice in six months’ time at an agreed price. If the market price has risen above the agreed one by the time the option falls due, he gets the rice cheap and immediately sells it at a profit. On the other hand, if the price is lower, he is committed to buying rice at a higher price than its market value and makes a loss.

Farmers find such instruments useful because they actually want to sell a real commodity: rice. People using rice for food, or manufacturing foodstuffs that use it, want to buy the commodity. In this sort of transaction, the contract reduces the risk to both parties – though at a price. It amounts to a form of insurance: a guaranteed market at a guaranteed price, independent of shifts in the market value. It’s worth paying a small premium to avoid uncertainty. But most investors took out contracts in rice futures with the sole aim of making money, and the last thing the investor wanted was tons and tons of rice. They always sold it before they had to take delivery. So the main role of futures was to fuel financial speculation, and this was made worse by the use of rice as currency. Just as today’s gold standard creates artificially high prices for a substance (gold) that has little intrinsic value, and thereby fuels demand for it, so the price of rice became governed by the trading of futures rather than the trading of rice itself. The contracts were a form of gambling, and soon the contracts themselves acquired a value, and could be traded as though they were real commodities. Moreover, although the amount of rice was limited by what the farmers could grow, there was no limit to the number of contracts for rice that could be issued.

The world’s major stock markets were quick to spot an opportunity to convert smoke and mirrors into hard cash, and they have traded futures ever since. At first, this practice did not of itself cause enormous economic problems, although it sometimes led to instability rather than the stability that is often asserted to justify the system. But around the year 2000, the world’s financial sector began to invent ever more elaborate variants on the futures theme, complex ‘derivatives’ whose value was based on hypothetical future movements of some asset. Unlike futures, for which the asset, at least, was real, derivatives might be based on an asset that was itself a derivative. No longer were banks buying and selling bets on the future price of a commodity like rice; they were buying and selling bets on the future price of a bet.

It quickly became big business. In 1998 the international financial system traded roughly $100 trillion in derivatives. By 2007 this had grown to one quadrillion US dollars. Trillions, quadrillions. . . we know these are large numbers, but how large? To put this figure in context, the total value of all the products made by the world’s manufacturing industries, for the last thousand years, is about 100 trillion US dollars, adjusted for inflation. That’s one tenth of one year’s derivatives trading. Admittedly the bulk of industrial production has occurred in the past fifty years, but even so, this is a staggering amount. It means, in particular, that the derivatives trades consist almost entirely of money that does not actually exist – virtual money, numbers in a computer, with no link to anything in the real world. In fact, these trades have to be virtual: the total amount of money in circulation, worldwide, is completely inadequate to pay the amounts that are being traded at the click of a mouse. By people who have no interest in the commodity concerned, and wouldn’t know what to do with it if they took delivery, using money that they don’t actually possess.

You don’t need to be a rocket scientist to suspect that this is a recipe for disaster. Yet for a decade, the world economy grew relentlessly on the back of derivatives trading. Not only could you get a mortgage to buy a house: you could get more than the house was worth. The bank didn’t even bother to check what your true income was, or what other debts you had. You could get a 125% self-certified mortgage – meaning you told the bank what you could afford and it didn’t ask awkward questions – and spend the surplus on a holiday, a car, plastic surgery, or crates of beer. Banks went out of their way to persuade customers to take out loans, even when they didn’t need them.

What they thought would save them if a borrower defaulted on their repayments was straightforward. Those loans were secured on your house. House prices were soaring, so that missing 25% of equity would soon become real; if you defaulted, the bank could seize your house, sell it, and get its loan back. It seemed foolproof. Of course it wasn’t. The bankers didn’t ask themselves what would happen to the price of housing if hundreds of banks were all trying to sell millions of houses at the same time. Nor did they ask whether prices could continue to rise significantly faster than inflation. They genuinely seemed to think that house prices could rise 10–15% in real terms every year, indefinitely. They were still urging regulators to relax the rules and allow them to lend even more money when the bottom dropped out of the property market.

Many of today’s most sophisticated mathematical models of financial systems can be traced back to Brownian motion, mentioned in Chapter 12. When viewed through a microscope, small particles suspended in a fluid jiggle around erratically, and Einstein and Smoluchowski developed mathematical models of this process and used them to establish the existence of atoms. The usual model assumes that the particle receives random kicks through distances whose probability distribution is normal, a bell curve. The direction of each kick is uniformly distributed – any direction has the same chance of happening. This process is called a random walk. The model of Brownian motion is a continuum version of such random walks, in which the sizes of the kicks and the time between successive kicks become arbitrarily small. Intuitively, we consider infinitely many infinitesimal kicks.

The statistical properties of Brownian motion, over large numbers of trials, are determined by a probability distribution, which gives the likelihood that the particle ends up at a particular location after a given time. This distribution is radially symmetric: the probability depends only on how far the point is from the origin. Initially the particle is very likely to be close to the origin, but as time passes, the range of likely positions spreads out as the particle gets more chance to explore distant regions of space. Remarkably, the time evolution of this probability distribution obeys the heat equation, which in this context is often called the diffusion equation. So the probability spreads just like heat.

After Einstein and Smoluchowski published their work, it turned out that much of the mathematical content had been derived earlier, in 1900, by the French mathematician Louis Bachelier in his PhD thesis. But Bachelier had a different application in mind: the stock and option markets. The title of his thesis was Théorie de la speculation (‘Theory of Speculation’). The work was not received with wild praise, probably because its subject-matter was far outside the normal range of mathematics at that period. Bachelier’s supervisor was the renowned and formidable mathematician Henri Poincaré, who declared the work to be ‘very original’. He also gave the game way somewhat, by adding, with reference to the part of the thesis that derived the normal distribution for errors: ‘It is regrettable that M. Bachelier did not develop this part of his thesis further.’ Which any mathematician would interpret as ‘that was the place where the mathematics started to get really interesting, and if only he’d done more work on that, rather than on fuzzy ideas about the stock market, it would have been easy to give him a much better grade.’ The thesis was graded ‘honorable’, a pass; it was even published. But it did not get the top grade of ‘très honorable’.

Bachelier in effect pinned down the principle that fluctuations of the stock market follow a random walk. The sizes of successive fluctuations conform to a bell curve, and the mean and standard deviation can be estimated from market data. One implication is that large fluctuations are very improbable. The reason is that the tails of the normal distribution die down very fast indeed: faster than exponential. The bell curve decreases towards zero at a rate that is exponential in the square of x. Statisticians (and physicists and market analysts) talk of two-sigma fluctuations, three-sigma ones, and so on. Here sigma (σ) is the standard deviation, a measure of how wide the bell curve is. A three-sigma fluctuation, say, is one that deviates from the mean by at least three times the standard deviation. The mathematics of the bell curve lets us assign probabilities to these ‘extreme events’, see Table 3.

minimum size of fluctuation |

probability |

σ |

0.3174 |

2σ |

0.0456 |

3σ |

0.0027 |

4σ |

0.000063 |

5σ |

0.0000006 |

Table 3 Probabilities of many-sigma events.

The upshot of Bachelier’s Brownian motion model is that large stock market fluctuations are so rare that in practice they should never happen. Table 3 shows that a five-sigma event, for example, is expected to occur about six times in every 10 million trials. However, stock market data show that they are far more common than that. Stock in Cisco Systems, a world leader in communications, has undergone ten 5-sigma events in the last twenty years, whereas Brownian motion predicts 0.003 of them. I picked this company at random and it’s in no way unusual. On Black Monday (19 October 1987) the world’s stock markets lost more than 20% of their value within a few hours; an event this extreme should have been virtually impossible.

The data suggest unequivocally that extreme events are nowhere near as rare as Brownian motion predicts. The probability distribution does not die way exponentially (or faster); it dies away like a power-law curve x–a for some positive constant a. In the financial jargon, such a distribution is said to have a fat tail. Fat tails indicate increased levels of risk. If your investment has a five-sigma expected return, then assuming Brownian motion, the chance that it will fail is less than one in a million. But if tails are fat, it might be much larger, maybe one in a hundred. That makes it a much poorer bet.

A related term, made popular by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, an expert in mathematical finance, is ‘black swan event’. His 2007 book The Black Swan became a major bestseller. In ancient times, all known swans were white. The poet Juvenal refers to something as ‘a rare bird in the lands, and very like a black swan’, and he meant that it was impossible. The phrase was widely used in the sixteenth century, much as we might refer to a flying pig. But in 1697, when the Dutch explorer Willem de Vlamingh went to the aptly named Swan River in Western Australia, he found masses of black swans. The phrase changed its meaning, and now refers to an assumption that appears to be grounded in fact, but might at any moment turn out to be wildly mistaken. Yet another term current is X-event, ‘extreme event’.

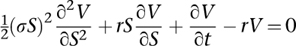

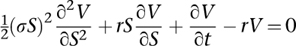

These early analyses of markets in mathematical terms encouraged the seductive idea that the market could be modelled mathematically, creating a rational and safe way to make unlimited sums of money. In 1973 it seemed that the dream might become real, when Fischer Black and Myron Scholes introduced a method for pricing options: the Black–Scholes equation. Robert Merton provided a mathematical analysis of their model in the same year, and extended it. The equation is:

It involves five distinct quantities – time t, the price S of the commodity, the price V of the derivative, which depends on S and t, the risk-free interest rate r (the theoretical interest that can be earned by an investment with zero risk, such as government bonds), and the volatility σ2 of the stock. It is also mathematically sophisticated: a second-order partial differential equation like the wave and heat equations. It expresses the rate of change of the price of the derivative, with respect to time, as a linear combination of three terms: the price of the derivative itself, how fast that changes relative to the stock price, and how that change accelerates. The other variables appear in the coefficients of those terms. If the terms representing the price of the derivative and its rate of change were omitted, the equation would be exactly the heat equation, describing how the price of the option diffuses through stock-price-space. This traces back to Bachelier’s assumption of Brownian motion. The other terms take additional factors into account.

The Black–Scholes equation was derived as a consequence of a number of simplifying financial assumptions – for instance, that there are no transaction costs and no limits on short-selling, and that it is possible to lend and borrow money at a known, fixed, risk-free interest rate. The approach is called arbitrage pricing theory, and its mathematical core goes back to Bachelier. It assumes that market prices behave statistically like Brownian motion, in which both the rate of drift and the market volatility are constant. Drift is the movement of the mean, and volatility is financial jargon for standard deviation, a measure of average divergence from the mean. This assumption is so common in the financial literature that it has become an industry standard.

There are two main kinds of option. In a put option, the buyer of the option purchases the right to sell a commodity or financial instrument at a specified time for an agreed price, if they so wish. A call option is similar, but it confers the right to buy instead of sell. The Black–Scholes equation has explicit solutions: one formula for put options, another for call options.1 If such formulas had not existed, the equation could still have been solved numerically and implemented as software. However, the formulas make it straightforward to calculate the recommended price, as well as yielding important theoretical insights.

The Black–Scholes equation was devised to bring a degree of rationality to the futures market, which it does very effectively under normal market conditions. It provides a systematic way to calculate the value of an option before it matures. Then it can be sold. Suppose, for instance, that a merchant contracts to buy 1000 tons of rice in 12 months’ time at a price of 500 per ton – a call option. After five months she decides to sell the option to anyone willing to buy it. Everyone knows how the market price for rice has been changing, so how much is that contract worth right now? If you start trading such options without knowing the answer, you’re in trouble. If the trade loses money, you’re open to the accusation that you got the price wrong and your job could be at risk. So what should the price be? Trading by the seat of your pants ceases to be an option when the sums involved are in the billions. There has to be an agreed way to price an option at any time before maturity. The equation does just that. It provides a formula, which anyone can use, and if your boss uses the same formula, he will get the same result that you did, provided you didn’t make errors of arithmetic. In practice, both of you would use a standard computer package.

The equation was so effective that it won Merton and Scholes the 1997 Nobel Prize in Economics.2 Black had died by then, and the rules of the prize prohibit posthumous awards, but his contribution was explicitly cited by the Swedish Academy. The effectiveness of the equation depended on the market behaving itself. If the assumptions behind the model ceased to hold, it was no longer wise to use it. But as time passed and confidence grew, many bankers and traders forgot that; they used the equation as a kind of talisman, a bit of mathematical magic that protected them against criticism. Black–Scholes not only provides a price that is reasonable under normal conditions; it also covers your back if the trade goes belly-up. Don’t blame me, boss, I used the industry standard formula.

The financial sector was quick to see the advantages of the Black–Scholes equation and its solutions, and equally quick to develop a host of related equations with different assumptions aimed at different financial instruments. The then-sedate world of conventional banking could use the equations to justify loans and trades, always keeping an eye open for potential trouble. But less conventional businesses would soon follow, and they had the faith of a true convert. To them, the possibility of the model going wrong was inconceivable. It became known as the Midas formula – a recipe for making everything turn to gold. But the financial sector forgot how the story of King Midas ended.

The darling of the financial sector, for several years, was a company called Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). It was a hedge fund, a private fund that spreads its investments in a way that is intended to protect investors when the market goes down, and make big profits when it goes up. It specialised in trading strategies based on mathematical models, including the Black–Scholes equation and its extensions, together with techniques such as arbitrage, which exploits discrepancies between the prices of bonds and the value that can actually be realised. Initially LTCM was a spectacular success, yielding returns in the region of 40% per year until 1998. At that point it lost $4.6 billion in under four months, and the Federal Reserve Bank persuaded its major creditors to bail it out to the tune of $3.6 billion. Eventually the banks involved got their money back, but LTCM was wound up in 2000.

What went wrong? There are as many theories as there are financial commentators, but the consensus is that the proximate cause of LTCM’s failure was the Russian financial crisis of 1998. Western markets had invested heavily in Russia, whose economy was heavily dependent on oil exports. The Asian financial crisis of 1997 caused the price of oil to slump, and the main casualty was the Russian economy. The World Bank provided a loan of $22.6 billion to prop the Russians up.

The ultimate cause of LTCM’s demise was already in place on the day it started trading. As soon as reality ceased to obey the assumptions of the model, LTCM was in deep trouble. The Russian financial crisis threw a spanner in the works that demolished almost all of those assumptions. Some factors had a bigger effect than others. Increased volatility was one of them. Another was the assumption that extreme fluctuations hardly ever occur: no fat tails. But the crisis sent the markets into turmoil, and in the panic, prices dropped by huge amounts – many sigmas – in seconds. Because all of the factors concerned were interrelated, these events triggered other rapid changes, so rapid that traders could not possibly know the state of the market at any instant. Even if they wanted to behave rationally, which people don’t do in a general panic, they had no basis upon which to do so.

If the Brownian model is right, events as extreme as the Russian financial crisis should occur no more often than once a century. I can remember seven from personal experience in the past 40 years: overinvestment in property, the former Soviet Union, Brazil, property (again), property (yet again), dotcom companies, and. . . oh, yes, property.

With hindsight, the collapse of LTCM was a warning. The dangers of trading by formula in a world that did not obey the cosy assumptions behind the formula were duly noted – and quickly ignored. Hindsight is all very well, but anyone can see the danger after a crisis has struck. What about foresight? The orthodox claim about the recent global financial crisis is that, like the first swan with black feathers, no one saw it coming.

That’s not entirely true.

The International Congress of Mathematicians is the largest mathematical conference in the world, taking place every four years. In August 2002 it took place in Beijing, and Mary Poovey, professor of humanities and director of the Institute for the Production of Knowledge at New York University, gave a lecture with the title ‘Can numbers ensure honesty?’3 The subtitle was ‘unrealistic expectations and the US accounting scandal’, and it described the recent emergence of a ‘new axis of power’ in world affairs:

This axis runs through large multinational corporations, many of which avoid national taxes by incorporating in tax havens like Hong Kong. It runs through investment banks, through nongovernmental organizations like the International Monetary Fund, through state and corporate pension funds, and through the wallets of ordinary investors. This axis of financial power contributes to economic catastrophes like the 1998 meltdown in Japan and Argentina’s default in 2001, and it leaves its traces in the daily gyrations of stock indexes like the Dow Jones Industrials and London’s Financial Times Stock Exchange 100 Index (the FTSE).

She went on to say that this new axis of power is intrinsically neither good nor bad: what matters is how it wields its power. It helped to raise China’s standard of living, which many of us would consider to be beneficial. It also encouraged a worldwide abandonment of welfare societies, replacing them by a shareholder culture, which many of us would consider to be harmful. A less controversial example of a bad outcome is the Enron scandal, which broke in 2001. Enron was an energy company based in Texas, and its collapse led to what was then the biggest bankruptcy in American history, and a loss to shareholders of $11 billion. Enron was another warning, this time about deregulated accounting laws. Again, few heeded the warning.

Poovey did. She pointed to the contrast between the traditional financial system based on the production of real goods, and the emerging new one based on investment, currency trading, and ‘complex wagers that future prices would rise or fall’. By 1995 this economy of virtual money had overtaken the real economy of manufacturing. The new axis of power was deliberately confusing real and virtual money: arbitrary figures in company accounts and actual cash or commodities. This trend, she argued, was leading to a culture in which the values of both goods and financial instruments were becoming wildly unstable, liable to explode or collapse at the click of a mouse.

The article illustrated these points using five common financial techniques and instruments, such as ‘mark to market accounting’, in which a company sets up a partnership with a subsidiary. The subsidiary buys a stake in the parent company’s future profits; the money involved is then recorded as instant earnings by the parent company while the risk is relegated to the subsidiary’s balance sheet. Enron used this technique when it changed its marketing strategy from selling energy to selling energy futures. The big problem with bringing forward potential future profits in this manner is that they cannot then be listed as profits next year. The answer is to repeat the manoeuvre. It’s like trying to drive a car without brakes by pressing ever harder on the accelerator. The inevitable result is a crash.

Poovey’s fifth example was derivatives, and it was the most important of them all because the sums of money involved were so gigantic. Her analysis largely reinforces what I’ve already said. Her main conclusion was: ‘Futures and derivatives trading depends upon the belief that the stock market behaves in a statistically predictable way, in other words, that mathematical equations accurately describe the market.’ But she noted that the evidence points in a totally different direction: somewhere between 75% and 90% of all futures traders lose money in any year.

Two types of derivative were particularly implicated in creating the toxic financial markets of the early twenty-first century: credit default swaps and collateralised debt obligations. A credit default swap is a form of insurance: pay your premium and you collect from an insurance company if someone defaults on a debt. But anyone could take out such insurance on anything. They didn’t have to be the company that owed, or was owed, the debt. So a hedge fund could, in effect, bet that a bank’s customers were going to default on their mortgage payments – and if they did, the hedge fund would make a bundle, even though it was not a party to the mortgage agreements. This provided an incentive for speculators to influence market conditions to make defaults more likely. A collateralised debt obligation is based on a collection (portfolio) of assets. These might be tangible, such as mortgages secured against real property, or they might be derivatives, or they might be a mixture of both. The owner of the assets sells investors the right to a share of the profits from those assets. The investor can play it safe, and get first call on the profits, but this costs them more. Or they can take a risk, pay less, and be lower down the pecking order for payment.

Both types of derivative were traded by banks, hedge funds, and other speculators. They were priced using descendants of the Black–Scholes equation, so they were considered to be assets in their own right. Banks borrowed money from other banks, so that they could lend it to people who wanted mortgages; they secured these loans with real property and fancy derivatives. Soon everyone was lending huge sums of money to everyone else, much of it secured on financial derivatives. Hedge funds and other speculators were trying to make money by spotting potential disasters and betting that they would happen. The value of the derivatives concerned, and of real assets such as property, was often calculated on a mark to market basis, which is open to abuse because it uses artificial accounting procedures and risky subsidiary companies to represent estimated future profit as actual present-day profit. Nearly everyone in the business assessed how risky the derivatives were using the same method, known as ‘value at risk’. This calculates the probability that the investment might make a loss that exceeds some specified threshold. For example, investors might be willing to accept a loss of a million dollars if its probability were less than 5%, but not if it were more likely. Like Black–Scholes, value at risk assumes that there are no fat tails. Perhaps the worst feature was that the entire financial sector was estimating its risks using exactly the same method. If the method were at fault, this would create a shared delusion that the risk was low when in reality it was much higher.

It was a train crash waiting to happen, a cartoon character who had walked a mile off the edge of the cliff and remained suspended in mid-air only because he flatly refused to take a look at what was under his feet. As Poovey and others like her had repeatedly warned, the models used to value the financial products and estimate their risks incorporated simplifying assumptions that did not accurately represent real markets and the dangers inherent in them. Players in the financial markets ignored these warnings. Six years later, we all found out why this was a mistake.

Perhaps there is a better way.

The Black–Scholes equation changed the world by creating a booming quadrillion-dollar industry; its generalisations, used unintelligently by a small coterie of bankers, changed the world again by contributing to a multitrillion-dollar financial crash whose ever more malign effects, now extending to entire national economics, are still being felt worldwide. The equation belongs to the realm of classical continuum mathematics, having its roots in the partial differential equations of mathematical physics. This is a realm in which quantities are infinitely divisible, time flows continuously, and variables change smoothly. The technique works for mathematical physics, but it seems less appropriate to the world of finance, in which money comes in discrete packets, trades occur one at a time (albeit very fast), and many variables can jump erratically.

The Black–Scholes equation is also based on the traditional assumptions of classical mathematical economics: perfect information, perfect rationality, market equilibrium, the law of supply and demand. The subject has been taught for decades as if these things are axiomatic, and many trained economists have never questioned them. Yet they lack convincing empirical support. On the few occasions when anyone does experiments to observe how people make financial decisions, the classical scenarios usually fail. It’s as though astronomers had spent the last hundred years calculating how planets move, based on what they thought was reasonable, without actually taking a look to see what they really did.

It’s not that classical economics is completely wrong. But it’s wrong more often that its proponents claim, and when it does go wrong, it goes very wrong indeed. So physicists, mathematicians, and economists are looking for better models. At the forefront of these efforts are models based on complexity science, a new branch of mathematics that replaces classical continuum thinking by an explicit collection of individual agents, interacting according to specified rules.

A classical model of the movement of the price of some commodity, for example, assumes that at any instant there is a single ‘fair’ price, which in principle is known to everyone, and that prospective purchasers compare this price with a utility function (how useful the commodity is to them) and buy it if its utility outweighs its cost. A complex system model is very different. It might involve, say, ten thousand agents, each with its own view of what the commodity is worth and how desirable it is. Some agents would know more than others, some would have more accurate information than others; many would belong to small networks that traded information (accurate or not) as well as money and goods.

A number of interesting features have emerged from such models. One is the role of the herd instinct. Market traders tend to copy other market traders. If they don’t, and it turns out that the others are on to a good thing, their bosses will be unhappy. On the other hand, if they follow the herd and everyone’s got it wrong, they have a good excuse: it’s what everyone else was doing. Black–Scholes was perfect for the herd instinct. In fact, virtually every financial crisis in the last century has been pushed over the edge by the herd instinct. Instead of some banks investing in property and others in manufacturing, say, they all rush into property. This overloads the market, with too much money seeking too little property, and the whole thing comes to bits. So now they all rush into loans to Brazil, or to Russia, or back into a newly revived property market, or lose their collective marbles over dotcom companies – three kids in a room with a computer and a modem being valued at ten times the worth of a major manufacturer with a real product, real customers, and real factories and offices. When that goes belly-up, they all rush into the subprime mortgage market. . .

That’s not hypothetical. Even as the repercussions of the global banking crisis reverberate through ordinary people’s lives, and national economies flounder, there are signs that no lessons have been learned. A rerun of the dotcom fad is in progress, now aimed at social networking websites: Facebook has been valued at $100 billion, and Twitter (the website where celebrities send 140-character ‘tweets’ to their devoted followers) has been valued at $8 billion despite never having made a profit. The International Monetary Fund has also issued a strong warning about exchange traded funds (ETFs), a very successful way to invest in commodities like oil, gold, or wheat without actually buying any. All of these have gone up in price very rapidly, providing big profits for pension funds and other large investors, but the IMF has warned that these investment vehicles have ‘all the hallmarks of a bubble waiting to burst. . . reminiscent of what happened in the securitisation market before the crisis’. ETFs are very like the derivatives that triggered the credit crunch, but secured in commodities rather than property. The stampede into ETFs has driven commodity prices through the roof, inflating them out of all proportion to the real demand. Many people in the third world are now unable to afford staple foodstuffs because speculators in developed countries are taking big gambles on wheat. The ousting of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt was to some extent triggered by huge increases in the price of bread.

The main danger is that ETFs are starting to be repackaged into further derivatives, like the collateralised debt obligations and credit default swaps that burst the subprime mortgage bubble. If the commodities bubble bursts, we could see a rerun of the collapse: just delete ‘property’ and insert ‘commodities’. Commodity prices are very volatile, so ETFs are high-risk investments – not a great choice for a pension fund. So once again investors are being encouraged to take ever more complex, and ever more risky, bets, using money they don’t have to buy stakes in things they don’t want and can’t use, in pursuit of speculative profits – while the people who do want those things can no longer afford them.

Remember the Dojima rice exchange?

Economics is not the only area to discover that its prized traditional theories no longer work in an increasingly complex world, where the old rules no longer apply. Another is ecology, the study of natural systems such as forests or coral reefs. In fact, economics and ecology are uncannily similar in many respects. Some of the resemblance is illusory: historically each has often used the other to justify its models, instead of comparing the models with the real world. But some is real: the interactions between large numbers of organisms are very like those between large numbers of stock market traders.

This resemblance can be used as an analogy, in which case it is dangerous because analogies often break down. Or it can be used as a source of inspiration, borrowing modelling techniques from ecology and applying them in suitably modified form to economics. In January 2011, in the journal Nature, Andrew Haldane and Robert May outlined some possibilities.4 Their arguments reinforce several of the messages earlier in this chapter, and suggest ways of improving the stability of financial systems.

Haldane and May looked at an aspect of the financial crisis that I’ve not yet mentioned: how derivatives affect the stability of the financial system. They compare the prevailing view of orthodox economists, which maintain that the market automatically seeks a stable equilibrium, with a similar view in 1960s ecology, that the ‘balance of nature’ tends to keep ecosystems stable. Indeed, at that time many ecologists thought that any sufficiently complex ecosystem would be stable in this way, and that unstable behaviour, such as sustained oscillations, implied that the system was insufficiently complex. We saw in Chapter 16 that this is wrong. In fact, current understanding indicates exactly the opposite. Suppose that a large number of species interact in an ecosystem. As the network of ecological interactions becomes more complex through the addition of new links between species, or the interactions become stronger, there is a sharp threshold beyond which the ecosystem ceases to be stable. (Here chaos counts as stability; fluctuations can occur provided they remain within specific limits.) This discovery led ecologists to look for special types of interaction network, unusually conducive to stability.

Might it be possible to transfer these ecological discoveries to global finance? There are close analogies, with food or energy in an ecology corresponding to money in a financial system. Haldane and May were aware that this analogy should not be used directly, remarking: ‘In financial ecosystems, evolutionary forces have often been survival of the fattest rather than the fittest.’ They decided to construct financial models not by mimicking ecological models, but by exploiting the general modelling principles that had led to a better understanding of ecosystems.

They developed several economic models, showing in each case that under suitable circumstances, the economic system would become unstable. Ecologists deal with an unstable ecosystem by managing it in a way that creates stability. Epidemiologists do the same with a disease epidemic; this is why, for example, the British government developed a policy of controlling the 2001 foot-and-mouth epidemic by rapidly slaughtering cattle on farms near any that proved positive for the disease, and stopping all movement of cattle around the country. So government regulators’ answer to an unstable financial system should be to take action to stabilise it. To some extent they are now doing this, after an initial panic in which they threw huge amounts of taxpayers’ money at the banks but omitted to impose any conditions beyond vague promises, which have not been kept.

However, the new regulations largely fail to address the real problem, which is the poor design of the financial system itself. The facility to transfer billions at the click of a mouse may allow ever-quicker profits, but it also lets shocks propagate faster, and encourages increasing complexity. Both of these are destabilising. The failure to tax financial transactions allows traders to exploit this increased speed by making bigger bets on the market, at a faster rate. This also tends to create instability. Engineers know that the way to get a rapid response is to use an unstable system: stability by definition indicates an innate resistance to change, whereas a quick response requires the opposite. So the quest for ever greater profits has caused an ever more unstable financial system to evolve.

Building yet again on analogies with ecosystems, Haldane and May offer some examples of how stability might be enhanced. Some correspond to the regulators’ own instincts, such as requiring banks to hold more capital, which buffers them against shocks. Others do not; an example is the suggestion that regulators should focus not on the risks associated with individual banks, but on those associated with the entire financial system. The complexity of the derivatives market could be reduced by requiring all transactions to pass through a centralised clearing agency. This would have to be extremely robust, supported by all major nations, but if it were, then propagating shocks would be damped down as they passed through it.

Another suggestion is increased diversity of trading methods and risk assessment. An ecological monoculture is unstable because any shock that occurs is likely to affect everything simultaneously, in the same way. When all banks are using the same methods to assess risk, the same problem arises: when they get it wrong, they all get it wrong at the same time. The financial crisis arose in part because all of the main banks were funding their potential liabilities in the same way, assessing the value of their assets in the same way, and assessing their likely risk in the same way.

The final suggestion is modularity. It is thought that ecosystems stabilise themselves by organising (through evolution) into more or less self-contained modules, connected to each other in a fairly simple manner. Modularity helps to prevent shocks propagating. This is why regulators worldwide are giving serious consideration to breaking up big banks and replacing them by a number of smaller ones. As Alan Greenspan, a distinguished American economist and former chairman of the Federal Reserve of the USA said of banks: ‘If they’re too big to fail, they’re too big.’

Was an equation to blame for the financial crash, then?

An equation is a tool, and like any tool, it has to be wielded by someone how knows how to use it, and for the right purpose. The Black–Scholes equation may have contributed to the crash, but only because it was abused. It was no more responsible for the disaster than a trader’s computer would have been if its use led to a catastrophic loss. The blame for the failure of tools should rest with those who are responsible for their use. There is a danger that the financial sector may turn its back on mathematical analysis, when what it actually needs is a better range of models, and – crucially – a solid understanding of their limitations. The financial system is too complex to be run on human hunches and vague reasoning. It desperately needs more mathematics, not less. But it also needs to learn how to use mathematics intelligently, rather than as some kind of magical talisman.