WHEN ONE CONSIDERS that the two men who did more than anybody to make Woodstock one of America’s great music towns were both Jewish, it is a curious irony that the man who founded the town’s first art colony over half a century earlier was—like so many otherwise educated people of his generation—a virulent anti-Semite.

What Albert Grossman and Bob Dylan (né Zimmerman) thought of Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead has not been recorded, but Dylan bought his Woodstock house on Camelot Road from Whitehead’s son Peter and probably did not confront him about his late father’s distaste for Jews. By the same token, Peter Whitehead had probably evolved far enough beyond his father’s ingrained prejudice against “Hebrews” not to stall the sale of Hi Lo Ha. The anti-Semitism that had been rife throughout New York state had in any case ebbed by 1965, when Dylan bought the house as a domestic base for his wife-to-be, her four-year-old daughter, and the baby boy they were expecting. There were no longer any hotels in the area that catered—as Woodstock’s Irvington Arms had done as late as the thirties—to “Gentiles Only.” And in the second decade of the twenty-first century, when numerous Jewish Americans make their first or second homes in or around Woodstock, it’s hard to conceive of a time when this was an issue at all.

His anti-Semitism aside, what Ralph Whitehead found in the verdant foothills of Woodstock’s Overlook Mountain was what Bob Dylan found there sixty-odd years later: a place of refuge, a bolt-hole of wooded bliss where a person could breathe deeply and create in peace. The same went for Dylan’s manager in Bearsville, a mile or so southwest. “I once asked Albert why he’d moved up here,” says Woodstock singer-songwriter Robbie Dupree. “He said, ‘Clean air and clean water.’”**

Whitehead had been casting about for a pastoral paradise for some time when his friend Bolton Coit Brown happened upon Woodstock in the spring of 1902. The wealthy son of a Yorkshire felt-mill owner, Whitehead had fallen under the spell of writer-artists John Ruskin and William Morris, who lamented the effects of the Industrial Revolution on the human soul and the artistic spirit. In this he was in accord with the New England transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, who both proselytized for retreats into the bosom of nature.

What Bolton Brown saw in 1902 was a more or less unspoiled landscape that for five thousand years had been home to Native Americans: indigenous peoples who had lived in rock shelters on Overlook and hunted in the surrounding forests till their lives were traumatically interrupted by immigrant invaders from Germany and the Netherlands. After the Esopus Wars of 1660 and 1663, when Dutch soldiers brought gifts of destruction and disease, Indians were driven back from their historical homeland and ever higher into the mountains. Forty years later, a group of Esopus Indians sold off Woodstock’s best land to Hendricks Beekman, whose name still lends itself to the self-styled “Oldest Inn in America” across the Hudson River in Rhinebeck. By the time Beekman died in 1716, many of Woodstock’s Native Americans were gone.

The indigenous spirit of the place lived on, however. “There was this thing about it having been a burial ground,” says Procol Harum lyricist Keith Reid, a regular visitor to Woodstock in the late sixties. “It was considered that there was some real bad karma and people shouldn’t be living there. Our band were doing some Ouija board stuff and thought they’d summoned up this Indian chief who was telling them to leave.” Sixties hippies weren’t the only people to speak of the power of Overlook and its ancient burial sites. To this day it is almost a local assumption that the mountain exercises a mystical influence over Woodstock. The fact that one of America’s largest Buddhist monasteries stands on Mead’s Mountain Road, halfway up Overlook, lends weight to this conviction. “The Tibetans say Woodstock is on a major ley line,” says Elliott Landy. “There’s a certain energy right in this area. It doesn’t exist in Saugerties, and it doesn’t exist down in Hurley. When you come up Route 375 and you see those mountains, something changes in you.”

“It always was a mecca, a power spot,” says Maria Muldaur, who first visited the town as a Greenwich Village bohemian in the late fifties. “There are other perfectly cute towns in the Catskills, but there’s some mojo there, some spirit that Whitehead found.”

By the start of the American Revolution in 1776, farmers—mainly Dutch tenants of landowner Robert Livingston—were living in and around Woodstock in forest clearings. There were sawmills on the Sawkill River, one of them owned by Livingston, who gave the settlement its new name after people had referred to the area for years by the Algonquian word Waghkonk (“at or near a mountain”). With its allusion to the small English town of the same name in Oxfordshire, “Woodstock” derives from the Saxon wudestoc (which can mean both a clearing in a wood or a tree stump).

It took time for Woodstock to recover from the American Revolution, when its inhabitants were under constant threat from British raiders and their Indian allies. The settlement was all but deserted at the revolution’s end in 1783, yet six years later it received township status, covering a vast and unwieldy area of over 450 square miles. Early Woodstockers survived through a combination of farming, hunting, and lumbering, but there were also apple orchards and cider mills, together with a very smelly tannery in the heart of the village.

In the early years of the new century there were even glassmaking factories in the Sawkill valley. Working at one of them were a father and son, Lewis Edson Sr. and Jr., who have a claim to being Woodstock’s first musicians of any note: in 1800 Edson Jr. even published a collection of hymns and songs entitled The Social Harmonist. Glassmaking brought money to Woodstock, increasing its population and bringing the first bank and post office to the area. Another source of employment came from the quarrying of bluestone, much of which found its way down the Hudson to New York City.

Through the tumultuous nineteenth century of the anti-rent wars—and of the Civil War itself—Woodstock slowly emerged from ancient country customs that included a pervasive belief in witchcraft. Churches and schools were built in the town. Tourists began visiting, seduced by descriptions of the Hudson Valley in best-selling novels by Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper. In August 1846 Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson Valley school of painters, climbed Woodstock’s most famous mountain and coined the phrase “the Overlook” after seeing its south peak.

Such was Overlook’s appeal to romantic travelers that plans for a hotel at its summit were made within two years of Cole’s climb. The Overlook Mountain House opened its doors in June 1871 and—in late 1873—was visited by President Ulysses S. Grant. Artists and consumptives followed, though rarely in numbers sufficient to make the place financially viable. The Mountain House—and similar travelers’ hostelries, such as George Mead’s boarding house—helped turn Woodstock into a semifashionable summer resort.

It was the view from the Mountain House that convinced Bolton Brown he had found what Ralph Whitehead and his American wife, Jane Byrd McCall, were looking for. “Like Balboa, from his ‘peak in Darien,’” Brown recalled of that May day, “I first saw my South Sea. South indeed it was and wide and almost as blue as the sea, that extraordinarily beautiful view, amazing in extent.”

Brown also did his homework on the issue of “Hebrews.” Having ascertained that Woodstock had resisted the tide of New York City Jews that engulfed the Catskills every sultry summer, he urged the Whiteheads to join him in the town as soon as possible. By the late summer, the prospect of a harsh winter notwithstanding, clearing and construction had begun on 1,500 acres of Mount Guardian, acquired somewhat ruthlessly half a mile northwest of Woodstock’s center.

A rural art colony was hardly a new phenomenon in America. Inspired by Monet and his fellow French impressionists at Giverny, artists and students had established such retreats all over the United States in the late nineteenth century. One of the earliest was the Palenville colony established by Asher B. Durand, a friend of Thomas Cole’s who specialized in views of local beauty spots like Kaaterskill Clove. Byrdcliffe—the name an amalgam of the middle names of Whitehead and his wife—was new only in its greater emphasis on the Arts and Crafts movement inspired by Ruskin and Morris.

So deeply was Whitehead influenced by Ruskin, whose lectures he’d heard as a student at Oxford, that he walked away from his family’s business and spent a decade traveling and immersing himself in the works of Dante Alighieri. In 1890 he journeyed to America and met McCall, marrying her in New Hampshire two years later. After establishing the small Arcady Colony near Santa Barbara—and following an affair with an opium-smoking heiress in that Californian coastal town—Whitehead met with two of his followers, Brown and Hervey White, and resolved to scout locations for a new colony on the East Coast.

It took the better part of a decade to complete the construction of Byrdcliffe’s many buildings. In June 1903, when the colony began life, Whitehead published “A Plea for Manual Work,” a manifesto in which he argued that “living in peaceful country places” while working at handicrafts and enjoying the arts would bring “repose” to Americans stressed by life in cities. Joining the Whiteheads in the Utopian experiment were Brown, White, and others. For the entrenched Woodstock population of old Dutch and German farming families, the newcomers were a sight to behold. They might have read about bohemians in Paris or even Greenwich Village, but they hadn’t bargained on them showing up on their doorstep.

Few of the Byrdcliffe bohemians were more startling to the eye than Hervey White, hailed by some as Woodstock’s first hippie. Bearing a distinct resemblance to Levon Helm, he was a proud socialist—and closeted gay man—who wore his hair long and dispensed with hats and conventional trousers. Indeed, so much his own man was this Midwesterner that it took only two years for him to fall out with the controlling Whitehead. While the Byrdcliffe activities of furniture making, metalworking, weaving, and print-making continued, White set up camp south of Woodstock in the Hurley Patentee Woods, eventually founding the rival Maverick colony at the onset of the First World War.

Woodstock’s locals braced themselves for another shock when the Art Students League of New York—inspired by Byrdcliffe—chose to base its summer school in a former livery stable in the middle of town. In the summer months Woodstock was soon overrun by free-spirited students, establishing a kind of double life that persists in the town to this day. For while Woodstock was for decades a profoundly conservative place, its natives soon adapted to the influx of outsiders, if only because the arts (and the crafts) brought money into local shops and businesses. Natives even ignored the nude female models who posed al fresco in Woodstock’s woods and streams. Boarding house owners overcame moral scruples and profited from the patronage of aspiring young painters and poets, some of whom stayed on through the tough months of winter.

In November 1923 the Woodstock Artists Association was formed. Exhibiting as a group in New York, it gave rise to a Woodstock School of artists whose work broadly combined earthy immersion in Catskills landscapes with influences from European post-Impressionism and Cubism. Early members of the association included George Bellows, Konrad Cramer, and Lucile Blanch. By the end of the decade, several other renowned painters and sculptors—from Yasuo Kuniyoshi to John Flannagan—were living at least part-time in Woodstock.

MUSIC ASSUMED A more central role at the Maverick. When in 1915 a well was urgently needed to supply water to Hervey White’s colony, the Maverick Festival was born as a way to raise funds for it. This annual event soon attracted flocks of unconventional Greenwich Villagers to the colony, most attired in playfully outlandish costumes and enjoying entertainment that included modernist classical music while also extending to more spontaneous expressions of dancing, juggling, and even sack racing. By 1916 the Maverick had its own theatre, carved from a nearby bluestone quarry.

The festivals upped the ante in the uneasy relations between bohemians and townspeople. Writing in 1916 in The Wild Hawk—the Maverick’s own monthly publication—White confidently stated that “there are motives that bring opposites together.” He subsequently offered to decorate Woodstock’s public buildings. The offer was refused, and many Woodstockers continued to view the Maverick festivals with suspicion—even after the opening of a new wooden theatre in July 1924 brought to the colony such stars of the stage as Helen Hayes and Edward G. Robinson.**

And yet, as the years went by, increasing numbers of Woodstock natives felt curious enough about the neo-pagan (some said orgiastic) revelries at the Maverick to join in, donning their own eccentric attire. At least part of the reason for this was their appreciation of the dollars flowing into Woodstock via bohemian tourism. As Alf Evers noted in his epic Woodstock: History of an American Town, “an uneasy alliance between art and business had been formed.” It would be ever thus in this most singular of Catskills towns.

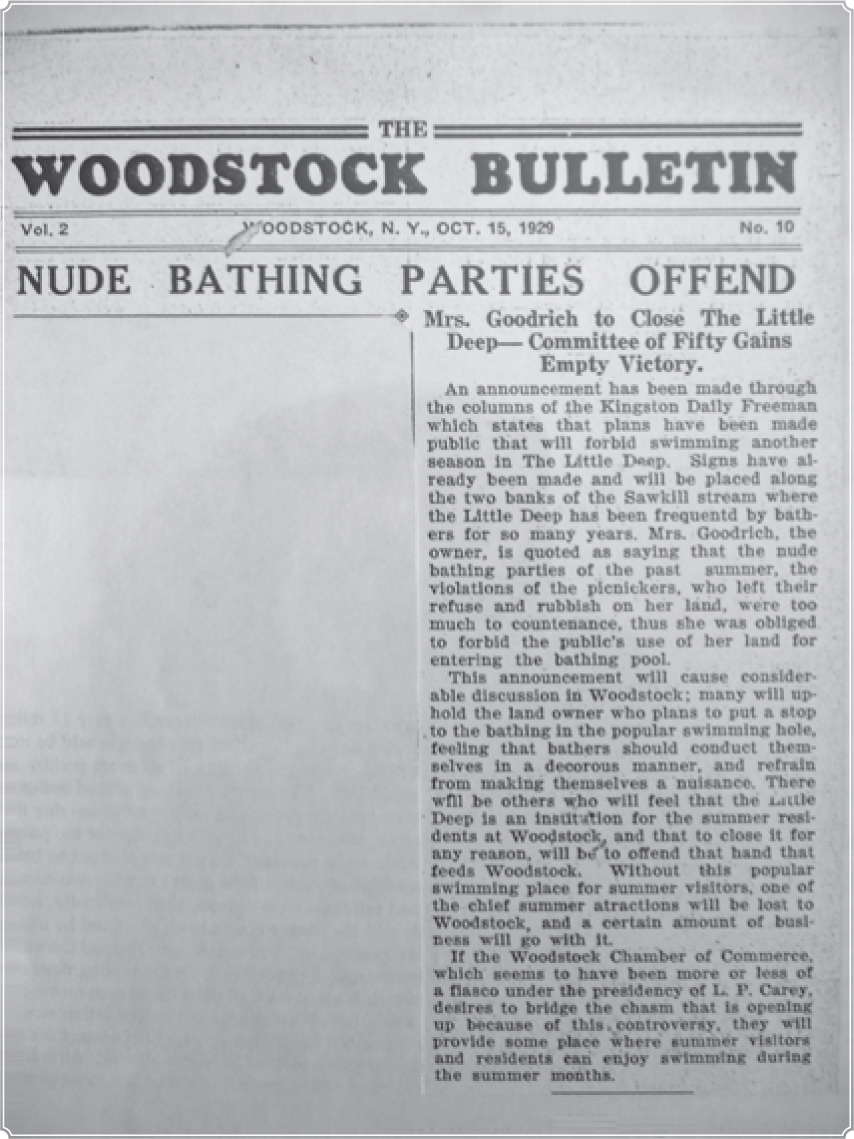

The Woodstock Bulletin, October 1929 (courtesy of Fern Malkine)

“If you come into Woodstock for the first time on a Saturday morning and land in the center of the village,” the New York Herald Tribune reported in a piece from the twenties, “you rub your eyes, blink, and wonder whether you have suddenly been magically transported to some carnival in southern Europe.” When future Woodstock Times publisher Geddy Sveikauskas first arrived in town in the late sixties, he was accosted by a female senior citizen who told him, “You people think you’ve invented it all, don’t you. Well, if you had lived here thirty years ago you’d have seen what an arts town really was like.”

The last Maverick Festival took place in 1931, after a boom decade in which Woodstock’s annual summer population swelled to over eight thousand and in which—to the distaste of most Byrdcliffe veterans—a new chamber of commerce was created. Underpinning the resentment was the anti-Semitism that made strange bedfellows of the Whiteheads and the older Woodstock families. When Jewish developer Gabriel Newgold began work on the Colony Hotel on Rock City Road, local newspapers referred to it as “the brick synagogue.” Yet increasing numbers of Jewish artists were moving into the area, assimilating as the Byrdcliffe craftsmen themselves had done. Alarm at the prospect of Woodstock’s ruin by business was, in any case, rendered irrelevant by the financial crash of 1929 and the devastating Depression that followed.

In that same year Ralph Whitehead died, though his widow kept Byrdcliffe going until her own death in 1955. If the thirties were as tough economically on Woodstock as on the rest of the country, there was the unexpected upside of Roosevelt’s Public Works of Art Project, which brought funding to nearly fifty of the town’s resident artists. This angered the townspeople, who resented their taxes going to support feckless creatives, and thus did the decades-old tension between artists and natives rumble on. “The town’s government was very right-wing all the way back to the Roosevelt era,” says Ed Sanders.

By the time America entered the Second World War, Woodstock’s year-round population had reached two thousand. It was hailed by Charles E. Gradwell, editor of the Overlook newspaper, as “the most cosmopolitan village in the world,” a place that included “men with beards, ballet dancers, farmers, flute players, business men, actors, poets, restaurateurs, potters, writers, weavers, painters, press agents, politicians, lawyers, historians, illustrators, cartoonists, philosophers, remittance men, educators, theatrical producers, wine merchants. . . .”

By 1960 Woodstock’s year-round population had all but doubled again, bringing in a wave of postwar artists that included Fletcher Martin, Manuel Bromberg, Ed Chavez, Doris Lee, and Wendell Jones. After Philip Guston won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1947, he moved first to Byrdcliffe and subsequently to the Maverick, where—as his daughter Musa wrote in her 1991 memoir Night Studio—“you stoked your own wood stove, pumped your own water, padded to the outhouse in the moonlight.”

“Woodstock was pretty quiet,” says the artist Bruce Dorfman, who first visited the town with the Art Students League in 1951. “But there were a lot of heavy hitters in the artistic community who lived there in the summers or year-round. Guston was probably the greatest of the painters here. Another Woodstock artist whose star has risen again is Kuniyoshi.”

“The town was small and safe and you knew everybody,” says Norma Cross, who spent summers in a cabin off the Maverick belonging to Russian-born artist Nahum Tschacbasov. “But it was pretty wild too. My parents were in their thirties and were partying and being outrageous.” Along with the artists came musicians such as composer Henry Cowell, who lived in the hamlet of Shady with his folk-song-collecting wife, Sidney; writers such as Casablanca screenwriter Howard Koch and CBS sports commentator Heywood Hale Broun; and actors such as John Garfield, who taught Cross how to swim, and Lee Marvin, who was a plumber before a lucky break gave him a part in a 1947 summer-stock production at the rebuilt playhouse.

Marvin was one of the many hard-drinking patrons of Woodstock’s most colorful bar. Four years after the end of Prohibition, Dick Stilwell had bought a disused stables on Rock City Road and turned it into the nautically themed S.S. Sea Horse, complete with portholes for windows and paintings by local artists on the walls. Macho sculptors bumped elbows with gin-swilling former madam Louise Hellstrom and Martini-sipping German plumber Adolf Heckeroth, to whom Marvin was apprenticed. Extramarital affairs began at the Sea Horse, and fights broke out as a result, though not as many as erupted up the road at the Brass Rail. When Stilwell collapsed and died at the Sea Horse, instead of summoning an ambulance, the patrons simply laid his corpse out on a Ping-Pong table and helped themselves to free drinks.

“I don’t know that my mother was one of those Sea Horse bohemians, but she knew that element,” says Jonathan Donahue. “She came up with her father in the Jewish exodus of the early forties. She’d seen Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie on Fifty-Second Street, so she brought that beatnik sensibility up with her. But it was different up here. There wasn’t an influx of people coming up from the city saying, ‘Where are the Beats?’”

The Sea Horse was one of several places in Woodstock where artists and natives mingled. “I remember my mom telling me how she would go to the Sea Horse and hang out with her cigarette holder and play pool,” says the Dobro player Cindy Cashdollar, whose family owned one of Woodstock’s dairy farms. Though for many years the town remained Republican, farmers’ kids like Cashdollar—who was born there in 1955—were schooled alongside the children of painters, slurping the same ice creams at Charlie’s Ice Cream Parlor. Potters from the Maverick shopped at the same hardware store as natives whose old way of life was now disappearing from the fields around Woodstock.

By the early sixties, Woodstock had properly joined the twentieth century. The New York State Thruway now made it possible to reach Manhattan by car in two hours, while a bridge linked Kingston to Rhinebeck across the Hudson. Route 28, the highway from Woodstock to Kingston, was widened and resurfaced. A supermarket and a branch of the Bank of Orange County appeared in town. The fifties had brought IBM and electric-fan manufacturer Rotron to the area, both building housing developments for their employees off Route 375. “There was a whole section of town where the IBMers lived and commuted to Kingston,” says Brian Hollander. “It made for a pretty interesting mix of people, since everybody had to go to the same places for their entertainment.”

Among the “entertainment” on offer in Woodstock was the folk music that was now taking middle-class American youth by storm.

![]()

* At the turn of the century Woodstock enjoyed a reputation—possibly self-cultivated—as the healthiest town in New York state. “Woodstock, Where People Seldom Die” ran a 1907 headline in one local newspaper.

* By the end of the decade, White’s theatre had a rival in the Woodstock Playhouse. Rebuilt in 1938 after an earlier fire, the theatre would play a major role in the town’s cultural life for decades. In 1970 the Band would record their aptly named Stage Fright there.