INSIDE THE COLONY Café’s old Mission-style interior, with its wraparound balcony and its original sign stating rates of “$1.50 and up, all with private baths,” a thin straggle of local groovers has drifted in from Woodstock’s Sunday night drizzle. Two youngish men are tuning a banjo and a Dobro, one a scrawny fellow in denim with short hair and a long beard. “We’re staying for as long as my daughter can stay awake,” a young mother says at an adjacent table.

Thanks to strictly enforced DUI laws in New York state, it’s all a long way from Woodstock’s glory years, when clubs along Tinker Street—and Mill Hill and Rock City Roads—heaved with roots-rocking revelers. “Woodstock in those days was comprised of freak musicians, local craftsmen, and a few artists,” says artist manager Mark McKenna. “It was low-key, and everybody kept their mouth shut. The cops were tolerant, and there was a friendly atmosphere. Now there are more cops in that town than in just about any other small town I’ve ever seen.”

“I used to go from the old Deanie’s to the Brass Rail to the Elephant to the Espresso to the Joyous Lake and then over to the Bear,” says Richard Heppner of the Woodstock Historical Society. “You could see three bands in a night if you wanted. But since DUI the town’s gotten more touristy and more policed. There is no real nightlife.”

The Colony’s main attraction tonight isn’t the two faux Appalachians but a kind of all-star Woodstock troupe fronted by Simi Stone, the female fiddle player I saw only two nights ago with Simone Felice (and who played with him in Bearsville side project the Duke and the King). Behind a Hammond keyboard sits the genial David Baron, whose father, Aaron, owned the mobile truck used to record the Band’s Stage Fright at the Woodstock Playhouse. Stone’s rhythm section consists of former Gang of Four bassist Sara Lee and drummer Zachary Alford, beat-keeper on the recent comeback album by Catskills resident David Bowie.

The music is very different from Felice’s—soulful, Motownish pop with blasting horns and Stone’s Little-Eva-meets-Amy-Winehouse vocals. When at the night’s end they encore with a cover of “Everyday People,” it’s impossible not to link this infectiously funky ensemble to their unisex mixed-race forebears Sly & the Family Stone, who lit up the Woodstock Festival with a storming wee-small-hours set that had the stardust hippies bumping and grinding on Max Yasgur’s hillside.

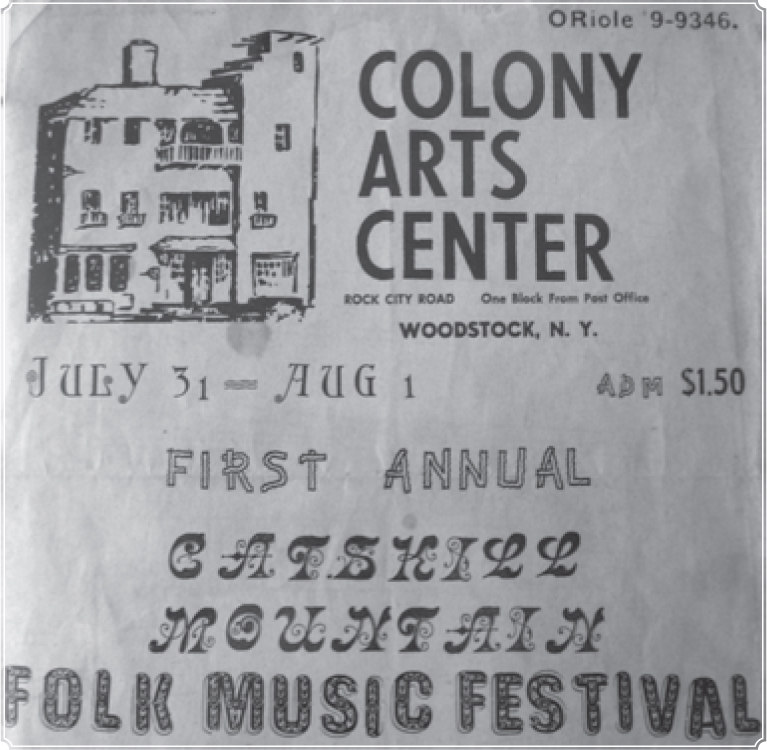

FIFTY-FIVE YEARS AGO, Gabriel Newgold’s old hotel resonated to very different sounds. The Colony Arts Center, as it was known in 1959, was the venue booked by Alf Evers for the First Annual Catskill Mountain Folk Festival, which brought together Woodstock’s premier exponents of folk song and mountain music, from seventy-five-year-old Mary Avery to twenty-nine-year-old Billy Faier.

Other performers included veterans “Squire” Elwyn Davis and “Bearded Bill” Spanhake, a fiddler and folklore humorist who regularly played at a sportsmen’s club in nearby Wittenberg. “They had square dances there,” says Dean Schambach, who moved to Woodstock from New York City in 1963. “Old Bill played the fiddle so that everybody just vibrated. These were great characters that people still revere, people you could trust and love.”

Also performing at Evers’s festival were fifty-one-year-old Sam Eskin, a Jewish folksong collector who’d moved to Woodstock in 1948, and his French protégée, Sonia Malkine, who’d come to America with her Surrealist painter husband Georges. It was just a year earlier, at a party of Eskin’s on Chimney Road, that Malkine’s voice had first been heard in public. Asked by painter Ed Chavez if she sang—he himself performed Mexican folk songs—she broke into an a cappella version of the exquisite thirteenth-century ballad “Robin,” silencing the entire party with the beauty of her voice. Within a week, Eskin had arranged the recording of an album for Moe Asch’s New York label Folkways, with Malkine accompanying herself on a lute.

Poster for the First Annual Catskill Mountain Folk Music Festival, summer 1959 (courtesy of Fern Malkine)

Country and barn dances had been staples of the town’s entertainment ever since Irish immigrants brought jigs and reels into the area in the previous century. By the fifties, farmers and artists alike gathered to enjoy the folk music of the Catskills. On Saturday nights there were square dances at the Irvington Arms, where a trio known as the Catskill Mountaineers performed for a well-lubricated mix of painters and natives. “That’s where I first became acquainted with the artistic people,” says Billy Faier, whose stepfather ran the town’s gas station. “It was all one big crowd: all the cultural people, the artists and the musicians. They all loved each other. I was a fifteen-year-old kid, and I met all these incredible people. It changed my life.”

Among the “artistic people” were the Ballantines, a well-heeled but politically enlightened family with a house in Woodstock. David Ballantine and his sister-in-law Betty were entrenched in Woodstock’s folk circle, David as an avid collector of 78s, Betty as a singer and guitarist who often played duets at the Irvington with the besotted Faier. It was through a friendship with the Ballantines that Sonia and Georges Malkine moved to the Maverick Colony in 1951 and then, two years later, bought a place of their own in nearby Shady.**

Many Woodstock artists and intellectuals—particularly those of a left-wing persuasion—had shown interest in folk music since the thirties. In June 1937 the blues singer Leadbelly, freed from prison after being “discovered” by the folklorist John Lomax, performed at the Zena home of John Varney for an audience that included Hervey White, fellow Maverick colonist Marion Bullard, and Overlook magazine editor Charles Gradwell. Later, as anticommunist hysteria grew in America, connections formed between Woodstock and summer camps such as Camp Woodland near Phoenicia, where Pete Seeger was welcomed in the wake of the House Un-American Activities Committee blacklist. Run by two veteran Greenwich Village radicals—one of whom, Herb Haufrecht, had helped assemble the print collection Folk Songs of the Catskills—Camp Woodland was where Seeger first heard not only those Catskills songs but the revolutionary Cuban anthem “Guantanamera.” It was also where he himself was first heard by Billy Faier, Alf Evers, and John Herald, who claimed that witnessing Seeger at Camp Woodland in 1954 was what inspired him to become a singer. It was in Woodstock, meanwhile, that Seeger met his wife, Toshi Ohta, whose father had designed theatre sets at the Maverick.

Despite all this, folk music remained low-key in Woodstock. Too small to compete with Greenwich Village or with the nascent Club 47 scene in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the small Catskills town was barely on the radar of the Urban Folk Revival. “There was always, within the community, an interest in folk music,” says Bruce Dorfman. “People listened to Woody Guthrie and Josh White, but it was very laid-back. Apart from some peripheral vision that somebody like Moe Asch had about the potential of a Billy Faier, the folkies in Woodstock were left alone. The impression I had was that they were sort of wistful about not being paid more attention but didn’t quite know what to do about it.”

In August 1962 Pete Seeger appeared at the Woodstock Playhouse—where, a year earlier, its new owner Edgar Rosenblum had started a Monday night folk series—to raise funds for Sam Eskin’s Ulster County Folklore Society. This newly formed body in turn sponsored the First Annual Woodstock Folk Festival, held on the weekend of September 14–16. Once again Eskin and Malkine were among the main attractions, together with Seeger himself; dulcimer player Mona Fletcher and her bagpipe-playing spouse, Frank; Greenwich Village singers Peter LaFarge and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott; and Barbara Moncure, who the following year would record the Folkways album Folksongs of the Catskills with singer-historian Harry Siemsen. “I must have been in Woodstock about twenty years before Albert [Grossman] or Bob [Dylan],” Jack Elliott said with some exaggeration in 2007. “Then I found out about Sam Eskin . . . a nice man and . . . one of the earlier Woodstock musicians. So there was that type of person up there then . . . but no famous ones, as there were later on.”

The Woodstock Folk Festival was a perfectly timed celebration of the fever that had seized the imagination of middle-class America since the first gatherings of folk singers in Washington Square in the late forties. “There were a lot of people from middle-class backgrounds who were looking for some cultural expression that they were lacking in the area where they were growing up,” said Happy Traum, a folk singer who has lived in Woodstock since the sixties. “We looked into blues and mountain music and cowboy songs and all the rest of it, and found in that a way of expressing ourselves.”

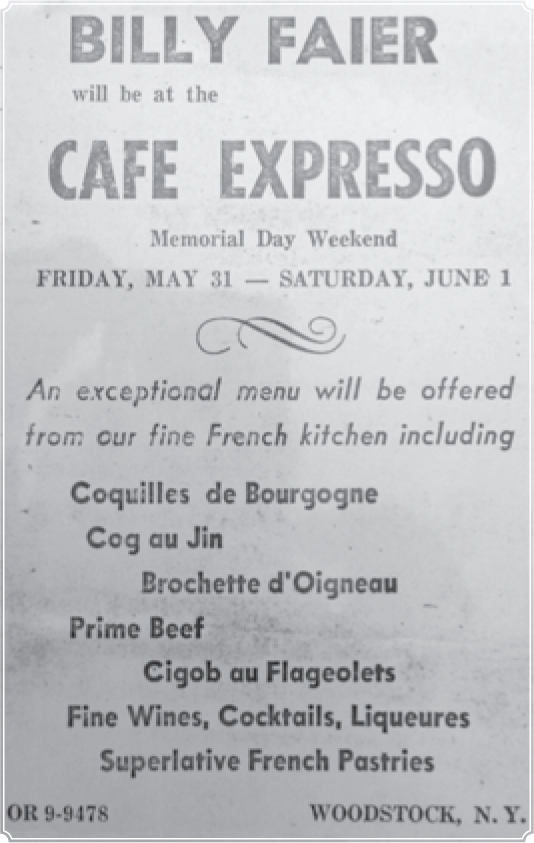

BY 1962, BILLY FAIER, another star of the Folk Festival, had been playing banjo for well over a decade. His hobo-esque career had taken him all over the United States, including California—in the company of Woody Guthrie and Jack Elliott—but he was now back in his beloved Woodstock, where he’d built himself a cabin in Lake Hill. Faier was also an habitué of the Café Espresso, Woodstock’s version of a Left Bank bistro, complete with red-and-white-check tablecloths and a jukebox that only played classical music. The café had started commercial life in 1921 as an ice-cream-and-sandwich parlor known as the Nook, celebrated in a song of Faier’s (“The Unpleasantness at the Nook”) that described a drunken fistfight between co-owners Jim Hamilton and Franklin “Bud” Drake. Hamilton and Drake had made up for long enough to transform the Nook into the Espresso Café in 1959, and then to sell it to Bernard and Mary Lou Paturel, who a year later changed the name again to the Café Espresso. Unimpressed by the entertainment that French-born Bernard brought up from the city—“one was a German folksinger, and there were some belly dancers and flamenco guitarists”—Faier suggested he hire a few up-and-coming folk singers instead.

Securing a regular slot for his own banjo instrumentals, Faier began booking acts for the Frenchman. “It was a weekend place,” he says. “Friday and Saturday nights and Sunday afternoon. You got fifty bucks, all the food you could eat, and a place to stay upstairs. Dave Van Ronk and Tom Paxton came up; so did Patrick Sky, Billy Batson, Jerry Moore, and Major Wiley.” Between 1962 and 1965, the Espresso also hosted appearances by Phil Ochs, Jack Elliott, Joan Baez, Tim Hardin, John Hammond Jr., the Reverend Gary Davis, Mississippi John Hurt, and other stars of the urban folk and country-blues revival. Sonia Malkine, who’d waited tables at the Nook, also performed at the Espresso, as did Sam Eskin, Dan and the Deacon, and other locals.

Billy Faier at the Café Expresso (sic), May–June 1963 (courtesy of Fern Malkine)

One cold day in the late winter of 1963, Happy Traum took a long bus trip from the city to play at the café. He had spent a summer in Woodstock with the Art Students League and even performed at a folk music night at the Woodstock Playhouse, but nothing quite prepared him for Tinker Street at the tail end of winter. “I remember getting off the bus,” he says, “and it seemed like the end of the world.” What made things worse was that Traum’s friend Bob Dylan was, that very night, due to play at New York’s Town Hall.** And yet being in Woodstock out of season gave Traum a window into what made the place so special: “There were a lot of town characters, and I got to meet some of those people around the big pot-bellied stove in the middle of the Espresso. It was a very bohemian atmosphere, very much like the Village except very rural.”

Among the “town characters” were Faier, who Traum had seen perform in the Village, and Sam Eskin and Sonia Malkine. Also present was Greenbriar Boys singer John Herald, who was spending time in the town to which his Armenian poet father had first brought him as a boy. “Johnnie had this soulful plaintive voice, and I had the biggest crush on him,” says Maria Muldaur, who gave Herald rides to and from Woodstock with her banjo-playing boyfriend Walter Grundy. “He showed us where all the sacred swimming holes were in Woodstock.” Herald would later take Traum and his wife, Jane, to Big Deep, a swimming hole in the Sawkill where art students had swum since the twenties. “It was the most idyllic place you could imagine, with the rope swing and the stream,” Traum says. “It all seemed so pristine and beautiful, and it gave me a sense that I wanted to be here.”

Another presence on the Village scene often came to the Espresso. Peter Yarrow had been a student along with Traum at New York’s High School of Music & Art, but the two had only been on nodding terms. Yarrow had been visiting Woodstock since 1945, when he was seven years old; he was there the day the Second World War ended.** The Yarrow family owned two cabins on Broadview Road, which ran parallel to the Sawkill south of Tinker Street, and Peter spent most of his summers there with his divorced mother, Vera. “Woodstock was completely warm and friendly,” he says. “It had no sense of its importance on the map in the world of tastemakers or moneymakers. It was not high-velocity, and everything was handmade.”

Milton Glaser, who designed album covers for the folk trio that Yarrow had joined in 1961, agrees: “In those days the artist colony was a glamorous thing, but only at a distance. As you got up close, it was just like any other poor town in the Catskills. We started going there in the mid to late fifties because it was a cheap place to go, but it hadn’t coalesced into anything discernible.”

Something discernible, however, was just around the corner. Within five years of Happy Traum’s Espresso gig in April 1963, Woodstock had changed from a place famous for its painters into a magnet for the popular music that shook sixties America to its core.

“For us it was an artists’ community,” said Jean Young, who moved to Woodstock with her husband Jim in 1963 and two years later opened the Juggler emporium on Tinker Street. “But once we got here, we realized that the musicians who came here were more advanced in what they were doing. So it shifted, for us, to things more concentrated on music.”

![]()

* David Ballantine, a friend of Lee Marvin’s, was the son of Maverick-actor-turned-sculptor E. J. Ballantine and his wife, Stella, niece of radical anarchist Emma Goldman. David’s brother Ian helped bring Penguin Books to the United States in 1939, before becoming the first president of Bantam in 1945 and later founding Ballantine Books.

* In September that year, the Folkways album Broadside Ballads, Vol. 1 would feature Traum singing the first recorded version of Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” as a member of Gil Turner’s New World Singers.

* An even earlier arrival was that of Allen Ginsberg, who spent at least one summer in Woodstock in the thirties with his parents, Louis and Naomi.