IT’S AS IF a bunch of midnight cowboys—or “citybillies,” as they once were called—has just stumbled into New York’s Town Hall from nearby Times Square. There are western hats everywhere, and endless banjos and mandolins. On the stage, raw young men and women lean into vintage microphones, awaiting cues and signals. Pre-empting the release of the bleak but deadpan-funny Inside Llewyn Davis—Joel and Ethan Coen’s film about the New York folk scene in 1961—this gathering of the music’s Great and Good is a one-night-only Village Preservation Society.

American folk music may now be quaintly fossilized—just as Inside Llewyn Davis may itself be a semi-jokey segue from the Coens’ earlier O Brother, Where Art Thou to Christopher Guest’s spoof A Mighty Wind—but the evening is a well-paced delight, less because of star turns by the likes of Joan Baez and Jack White than because of its sheer abundance of lovely songs: Tom Paxton’s “Last Thing on My Mind,” Ian Tyson’s “Four Strong Winds,” Hedy West’s “500 Miles,” Jackson C. Frank’s “Blues Run the Game,” and the oft-covered traditional “Green, Green Rocky Road.” Bob Dylan’s “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” is exquisitely rendered by Keb’ Mo’, Utah Phillips’s “Rock Salt and Nails” endearingly croaked by Dylan’s legendary sixties henchman Bob Neuwirth. Dylan himself is absent, but the show—like the film—fittingly closes with his song “Farewell.”

There is such pleasure in these songs of loss and longing, of distance and resistance: enough, at least, to remind us that for a long moment folk music did its bit, in the mighty line from Patti Smith’s closing anthem “People Have the Power,” to “wrestle power from fools.” It may be hard in late 2013 to hear this music as it was originally sung, but the concert says so much about how our culture clings to an organic Eden of acoustic roots in the digitized world of virtual connection. That it’s staged in a venue where Dylan played one of his breakthrough concerts—and where the ghosts of Guthrie, Leadbelly, and Van Ronk still lurk—gives it extra lift and poignancy.

ONE OF THE key sequences in Inside Llewyn Davis involves Davis (Oscar Isaac) hitching a ride to wintry Chicago in the company of a disdainful hophead of a jazz musician (John Goodman). Davis only just makes it to the icy Windy City but manages to bag an audition for Bud Grossman, manager of the Gate of Horn nightclub. Played by F. Murray Abraham as a sterner version of Columbia Records’ goatee-bearded A&R (artists and repertoire) chief Mitch Miller, Grossman listens to Davis and responds with the terse feedback that “I don’t see a lot of money here.” Quick to blow a golden opportunity, Davis shuffles back into the deep snow of the Chicago streets—just as Dave Van Ronk had done. “I got to Chicago,” Van Ronk said in 1966, “and he said, ‘I’ve got Muddy Waters and Memphis Slim here. What do I need with you?’ . . . And I stormed out.”

“I don’t see a lot of money here”: the harsh words are certainly of a piece with what the real-life owner of the Gate of Horn might have said to an aspiring troubadour. “The guy was a real asshole,” says Billy Faier, who played the Gate not long after it opened in 1955. “He was rude; he was arrogant. After I played he comes up to me, towering over me, and starts chewing me out in a loud voice about what a terrible performer I was.”

Albert Grossman, who was thirty-five in 1961 but always looked fifty, was a new type of impresario on the folk scene: saturnine, intimidating, greedy, the opposite of everything the folk revival was supposed to be about. He had opened the Gate of Horn after graduating from Roosevelt University with a degree in economics and working as an administrator for Chicago’s public housing authority—a job from which he was fired for “gross irregularities.” “He couldn’t get a job very easily after that,” said Les Brown, his original partner in the club. “He seemed very depressed, he had a lot of problems with women, and so we decided to set up a nightclub.”

The Gate of Horn was a hundred-seat room in the basement of the Rice Hotel on the city’s North Side, and everybody who was anybody in folk or country-blues played there. The club made stars of the bellowing African American singer Odetta and of Bob Gibson, a charismatic and influential Chicago native who headlined at the club within a year of first appearing there. “Albert had the first and only club in Chicago that reflected what was going on in terms of contemporary music,” says Paul Fishkin, who later ran Grossman’s record label, Bearsville. “He integrated Lenny Bruce with Odetta. He was truly of that generation.”

“Albert was a real hipster,” says blues keyboard player Barry Goldberg, who met him in the early sixties. “He set a precedent for management, for not being just a shyster but someone with a brain who was astute. He was on his way to becoming a major player. The way he looked at you, there was an immediate intimidation. You knew he could make it happen.”

Grossman even played his part in the rise of folk’s new princess. “He was a very generous man,” said Joan Baez, who was yet to break out of Boston and Cambridge. “Though he never managed me, his cajoling me to perform at the Gate of Horn when I was 18 marked the beginning of my career.” Unlike Odetta or Gibson—whose recommendation of her for the 1959 Newport Folk Festival broke her even bigger—Baez resisted Grossman’s managerial overtures. Bristling at his aggressive ambition, she not only turned him down but signed with the small Vanguard label rather than the corporate behemoth that was Columbia. Nor was she the only person to turn away from Grossman’s ruthlessness. Les Brown loathed him so much that, after Grossman’s death, he made a special trip to urinate on his grave.

One thing nobody doubted about Grossman was his commitment to folk music as an art form: like all the best music entrepreneurs he was in awe of true talent. “If the audience wasn’t attentive, if they really didn’t listen to the act, then they were asked to leave,” remembered Bob Gibson, who shared a North Side apartment with Grossman. “This was unheard of at the time.”

It was through his representation of Gibson and Odetta that Grossman first intersected with the record business in New York. It didn’t take long for him to figure out that if he was going to be a genuine force in music he needed to be in Greenwich Village. Having helped to plan the first Newport Folk Festival with its founder, George Wein, Grossman sold his interest in the Gate of Horn, moved into Wein’s apartment on Central Park West, and began the hunt for folk talent. “He told me that when he first came to New York, it was like a movie unfolding in front of his eyes,” says Michael Friedman, who began working for Grossman in 1968. “And then gradually he got pushed into the movie, having to deal with all the noise and the people.”

Making the move east with Grossman was his partner, John Court, who some said was the good cop to Grossman’s bad. The two men set up a temporary perch in the offices of Bert Block, who’d managed such jazz legends as Billie Holiday and Thelonious Monk. “Bert told me that he met them when they first arrived here,” says Michael Friedman. “They were, like, sitting on a milk crate with a phone.”

Grossman had a concept for a musical ménage à trois that he pitched to Dave Van Ronk and others.** When he heard a singer named Hamilton Camp in the Village, he packed him off to Chicago to join forces with Bob Gibson, hoping to complete the trio with a girl singer. But neither Camp nor Gibson was interested. Instead they formed a duo in 1961 and cut the best-selling album Gibson and Camp at the Gate of Horn. In the fall of 1959, however, Grossman was sitting at the Café Wha? on MacDougal Street and half-listening to a short set by Peter Yarrow. “He saw me perform and walked out in the middle of my show,” Yarrow says. “Later, after I was on Folk Sound USA, the first folk ‘spectacular’ on TV, he saw me rehearsing and said he’d like to talk to me. I went to the office on Central Park West, and our relationship started.”

“Albert had a real nose for talent,” says Jim Rooney, who booked acts at Cambridge’s new Club 47. “He didn’t have any money, he was sleeping on George Wein’s couch, he had Peter as a client, and that was it. So he was putting in his own money, and no, he wasn’t paying huge advances to these people. But no one else was paying them either.”

Though for a brief period he managed Yarrow as a solo act, Grossman saw the Cornell graduate as one-third of his dream trio. The leading candidate for the female place was a blonde named Mary Travers, then dating David Boyle. “She was young and beautiful in her own horsey way,” Boyle says. “She said, ‘Do you think I should do it?’ I told her to get into it, and they clicked.” Boyle did carpentry work for the third and final piece of Grossman’s puzzle. The only problem with Noel Stookey was his name. A comedic singer who regularly gigged at the Wha? and the Gaslight, Stookey swallowed his pride—or at least his name—and became the “Paul” of Peter, Paul & Mary. In a managerial masterstroke that would forever make record executives wary of him, Grossman courted Atlantic Records, who were primed to sign the trio, and then landed them an unprecedented five-year deal with Warner Brothers. “Albert allowed us to be what we were,” says Yarrow. “He made sure that we could evolve, and he had certain concepts about the sound. For instance, our voices were spread in a way that had not been done before, and the intimacy of that was totally different. When he thought the work was not good, he would literally say it was ‘bullshit’—at a time when not too many people used a term like that.”

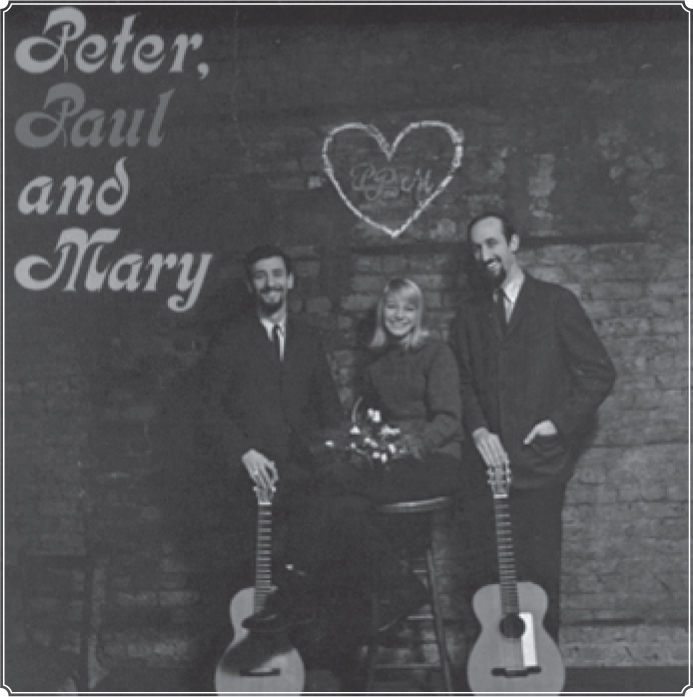

Grossman soon had a reputation for insisting on the best. For Peter, Paul & Mary’s debut album, released in May 1962, he hired top arranger Milt Okun to be their “musical director” and brought in Milton Glaser of Push Pin Studios to design the album’s cover. “He had this incredible vision,” says Jane Traum, wife of Happy. “It was a very conventional era, and who would have thought these off-center people would become such superstars?”

In 1962, when the trio’s rousing version of Pete Seeger’s anthem “If I Had a Hammer” hit number 10 on the singles chart, Jim Rooney caught them on Cape Cod. “It was an extremely professional and polished act that they had right from the start,” he says. “And that was all Albert’s doing. He had Chip Monck doing lighting when Chip was just starting out in that business. Everything was already first-class.”

Peter, Paul & Mary’s first album (1962)

While Peter, Paul & Mary earned Grossman his first big money, his private life remained altogether murkier. Few on the Village scene knew, for instance, that he was married to a bisexual, drug-addicted prostitute. “David Boyle can confirm this,” says Dean Schambach, who was busy making countertops for the new GrossCourt Management offices at 75 East Fifty-Fifth Street. “There were three girls—Betty, Sheila, and Jackie—who came to Albert’s office and solicited him. And I couldn’t believe I was seeing him come in the rear door of the Fat Black Pussycat with Betty Spencer, with snow on the shoulders of his cashmere coat. Because she was a hopeless junkie. But she was also beautiful and brilliant, and he thought that with instruction and guidance she might materialize into something wonderful. And that was Albert’s doom. It got grisly.”

“Albert was walking on the wild side,” says Peter Yarrow. “He had many friends who were on the edge of discovering new dimensions. It was Albert who introduced me to marijuana. I had never smoked a joint. There were many aspects to him that were adventurous, peripheral, and even dangerous.”

Doomed though his marriage may have been—the couple divorced after nine months—Grossman was now a player, a Village potentate. “He referred to his clients as ‘artists,’ and it was put that way in the contracts,” says John Byrne Cooke, who later road-managed acts for Grossman. “He imposed—on people who were not necessarily prone to adopt this position—greater respect for the musicians.”

Stories began to filter through about Grossman’s negotiation techniques, which relied heavily on the weapon of silence. “He would simply stare at you and say nothing,” recalled Charlie Rothschild, poached by Grossman from the Village club Gerde’s Folk City. “He wouldn’t volunteer any information, and that would drive people crazy. They would keep talking to fill the void, and say anything.” When Grossman did speak, people listened. “He had this compelling authority in his voice, which was very rich and deep,” says Dean Schambach. “He could sometimes get arrogant and splash you around. He would force you to go in his direction, but you couldn’t resist it. He knew how to play the Big Daddy role, because a lot of us were like orphans.”

As time went on, Grossman created a persona that distinguished him from the other managers in the business. “He came from Chicago in a suit and short hair, and he wound up looking like Ben Franklin,” says Paul Fishkin. “He was so hip-looking and such a part of the artists’ world that it was very hard for the other business guys to get a read on him and negotiate with him. Because he was nothing like them.”

“He was extremely eccentric and intimidating,” says Michael Friedman. “He used to keep his office so dark, and you’d sit so low in this chair in front of his desk that you couldn’t even really see him. There would just be this booming voice from the other side of the desk, and it scared the crap out of everybody.”

“Albert was a curious mixture of aggression and shyness,” says Milton Glaser. “In some cases he was so withdrawn, and in other cases he would just bully people into submission.” Glaser wondered if Grossman’s persona was simply a compensation for his outsider status: “Sometimes when people come from Chicago, they feel very intimated by New York, and with him there was certainly a kind of estrangement.” Peter Yarrow saw it differently: “I wouldn’t say Albert was shy so much as deliberately closed to certain people. With those he didn’t know, he could be immediately very combative if he felt they were pulling some kind of interpersonal quick-draw stuff—like, ‘Who’s got the dominant moment in this room right now?’ But there was a warmth and a delight and a joy and a sense of humor that he shared with all his artists.”

“Albert was a most interesting man,” said Edgar Cowan, who accompanied Canadian husband-and-wife duo Ian and Sylvia Tyson to New York in search of a manager. “A lot of people didn’t like him, but I liked him an awful lot. . . . I found him to be a fascinating guy; a very intellectual guy.” The Tysons, though, were under no illusion that Grossman was taking them on for their songs. “He signed us as much for our looks as the music,” Ian claimed. “He definitely saw us as a big commercial folk act. He saw in us our clean-cut Canadian naivety.”

And then there was the callow, tousle-headed boy who’d just blown into town from small-town Minnesota with a guitar and a head full of Woody Guthrie songs. Bobby Zimmerman looked about fifteen years old but affected the singing voice of a man of fifty. His day-to-day life was based on his Guthrie infatuation and the hipster-dropout persona he’d cobbled together from On the Road, The Catcher in the Rye, and Rebel Without a Cause. He called himself Bob Dylan—probably after the Welsh poet who’d drunk himself to death in the Village in 1953—and fabricated a past that read like a Beat novel. After he surfaced in the Village in January 1961, men were intrigued, and women wanted to mother him—even the ones who thought him a phony. He was naïve, intense, charming, and narcissistic in about equal measures. “At the beginning he wasn’t that big of a deal,” says Norma Cross, who waited on him at the Fat Black Pussycat. “At least I didn’t think of it that way. But it was always fun to see him and always interesting, because he was different from regular guys.”

That summer, Grossman heard Dylan for the first time. He also picked up on the buzz about the kid whose vibe was so different from the wholesomeness of Peter, Paul & Mary. To Dylan, meanwhile, Grossman resembled Sidney Greenstreet in The Maltese Falcon: “Not your usual shopkeeper,” he would note dryly in his Chronicles. In the eyes of New York Times critic Robert Shelton, whose review of Dylan’s set at Gerde’s Folk City on September 26 thrust him into the spotlight, the enigmatic manager was “a Cheshire cat in untouched acres of field mice.”

According to John Herald, whose Greenbriar Boys were headlining that night at Gerde’s, Dylan was in a state of high excitement before the show. “This was a real big deal, and he knew it,” Herald told author David Hajdu. “He was excited. He dressed in a certain way. He asked everybody what he should wear that night, what he should sing. . . .” By the time Shelton’s review ran, Grossman had homed in on Dylan, convinced he could either make him a star or make lots of money through his songs—preferably both. “Albert was sort of pursuing Bob,” says Dean Schambach, who observed Dylan up close as he was sound-checking one afternoon. “Bob was hard to get to know, because he was aloof and remote. But his driving inner force was so powerful, it forced you to love him. It electrified the audience’s awe and wonder, and Albert knew this.”

“Bobby was hot off the presses and sounding like a copy of Woody in his delivery and his point of view,” says Peter Yarrow. “Nobody initially thought of him as somebody who would transform music, but Albert came to me and asked me, ‘What do you think about my taking him on?’ And he was asking me for two reasons. One was, ‘Would you be averse to this for any reason?’ And two was, ‘Do you think it’s a good idea?’ And I said, ‘I love Bobby, and I think he’s amazing.’ Albert said, ‘He’s too good not to happen.’”

If dollar signs were flashing before Grossman’s eyes, he was prescient all the same. None of the other folk managers was convinced by the kid from Minnesota—or even too sure what he was all about. “Albert was the second choice for Bob at that point,” says Arline Cunningham, who worked for Woody Guthrie’s manager, Harold Leventhal. “Bob had done a little audition for us, but people in the office were like, ‘We’ve got Woody; what do we need with this kid?’” As it turned out, Dylan already had a manager named Roy Silver, an archetypal New York hustler who also looked after comedian Bill Cosby. (He had also been helped by Dave Van Ronk’s wife, Terri Thal.) Legend has it that Grossman flipped a coin with him to see who would get the white folk singer and who the black comedian. “Albert won the toss,” says Michael Friedman.

In June 1962, Grossman paid $10,000 to prize Dylan free of Silver. He was taking a chance on an artist who was hardly to everyone’s tastes, sang in an astringent voice, strummed his guitar in the most rudimentary manner, punctuated his Guthrie-esque phrasing with wheezy harmonica phrases, and could not have been described as good-looking. “I thought he was a terrible singer and a complete fake,” admitted guitarist Bruce Langhorne, who played on a Columbia session for Carolyn Hester that provided Dylan with his first New York studio experience. But Grossman heard what his fellow kingmakers could not: original language, a genuinely nonconformist stance, the authentic voice of postwar youth.

Consequently, what began was a father-son relationship that was mostly about protection—keeping Dylan from the imperatives of commercial crassness—but also about money. “Albert wanted to get into music publishing, which is where all the money is in the music business,” said Charlie Rothschild. “He started looking to sign folk singers who could write, and he started calling them poets.”

For Joan Baez, there was a “general strangeness and mystique” about Dylan. He was, she said, “already a legend by the time he got his foot into Gerde’s.” Grossman was simply hip enough to see the edge of intelligence and irreverence and, yes, weirdness that others could not. As a result he became almost as much of a legend as Dylan himself. “We heard about Albert before we ever met him,” says John Byrne Cooke, the urbane son of British broadcaster Alastair and a member of Club 47 regulars the Charles River Boys. “We heard that from the moment he signed Dylan he said, ‘Bob Dylan does not play coffeehouses; he plays concerts.’”**

Dylan knew enough about folk morality to know that, for many on the scene, Grossman was the enemy: a capitalist pig, or at least a capitalist bear. “He was kind of like a Colonel Tom Parker figure,” Dylan said in the 2005 documentary No Direction Home. “He was all immaculately dressed every time you’d see him. You could smell him coming.” Yet Dylan knew he needed Grossman to make his dreams come true. “A lot of Albert did in fact turn up in Bob,” noted Al Aronowitz, the New York Post journalist who became one of Dylan’s most ardent champions. “If I never got a straight answer out of Bob, I never got one of Albert either. [They] weren’t cut from the same cloth but from the same stone wall.”

By July 1962, in a contract that would give Grossman 20 percent of his overall earnings and 25 percent of his gross recording income, Dylan had signed to Grossman for seven years. He was already contracted to Columbia, whose blueblood A&R man John Hammond distrusted almost everything about Grossman and would soon be butting heads with him over Dylan.†† “The mere mention of Grossman’s name just about gave [Hammond] apoplexy,” Dylan would write in Chronicles.

Twelve months later, with Dylan feted by the folk establishment at that year’s Newport festival, money and radical politics converged in Peter, Paul & Mary’s version of his song “Blowin’ in the Wind.” “It was an act of pure premeditated genius,” says Peter Walker, who ran the Folklore Center in Boston. “The idea of taking Dylan, who had no commercial appeal, and connecting him to Peter, Paul & Mary was a one-two punch—the Dylan songs and the Peter, Paul & Mary act, which brought those political camps together. So everybody stepped back and let this thing happen.”

Yarrow told Dylan he might make as much as $5,000 from “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Unbeknownst to Dylan, who didn’t read his contracts very closely, Grossman would be making the same amount. In fact, Grossman was already wealthy enough that year to buy himself a Rolls Royce. To anyone who flinched at the commissions that he took from his clients—10 percent more than the industry standard—Grossman would respond that “every time you talk to me you’re 10 percent smarter than you were before.” And he was probably right: 75 percent of what Grossman made for a musician was usually at least 85 percent more than what most other managers would have brought in. “I thought he was incredible,” says Grossman’s friend Ronnie Lyons. “I was used to seeing groups getting offered 3 percent royalties and never getting paid. Albert was scoring 18 percent, 21 percent royalty deals for his artists and getting tour support. He had a master’s degree in theoretical economics, and he used it well.”

“In those days contracts were essentially indentured servitude for five or seven years with a fixed royalty rate,” says Jonathan Taplin, who later road-managed the Band for Grossman. “Albert introduced the idea that you could renegotiate a record deal in the middle of the contract. As soon as one of his artists began to get successful, Albert would say, ‘We’re gonna go on strike.’ He threatened that with Dylan at Columbia, and he did it with Peter, Paul & Mary too. People like Clive Davis and Mo Ostin loved Albert on one level and feared him on another.” (One of Grossman’s favorite threats to record labels was: “If the bird’s not happy, the bird don’t sing.”)

“What you see today in the music business is the result of Albert,” said record executive Bob Krasnow. “He changed the whole idea of what a negotiation was all about.”

![]()

* Grossman also wanted to turn Van Ronk into a novelty act, Olaf the Blues Singer, in order to prove that he was corruptible. “Integrity bothered Albert,” Van Ronk reflected years later. “He used to say there was no such thing as an honest man.”

* This wasn’t strictly true: Dylan was still playing coffeehouses in October 1962.

† After the pronounced failure of his Columbia debut album, Dylan was famously referred to in the company as “Hammond’s Folly.”