LEVON HELM AND his fellow Hawks had not performed together as a unit since the fall of 1965. Backing Dylan at Carnegie Hall on Guthrie songs that dipped back into the camaraderie of Big Pink—while also bringing Bob back into the bosom of the older folk guard—they were taking a night off from the recording sessions for their debut album at nearby A&R Studios. In his 1993 autobiography, Helm noted that “just as Bob was leaving Albert’s stable, we were arriving.”

With a new name for the group still undecided, Grossman had struck a deal with Alan Livingston at Capitol Records, the Los Angeles label whose acts included the Beatles and the Beach Boys. “Albert came in to see us, and he brought Robbie with him,” says Ken Mansfield, then Capitol’s West Coast promotion manager. “The idea was for him to do his thing, but he wanted a feel from a band member. And there was a dynamic in that meeting that I had never seen before, because Grossman knew he had all the cards. He would never smile, and you could just tell this guy was sharp—he was mean and he was tough. He was grilling us, and Robbie was sitting there observing each one of us. Because he was going to go back to the band and say what he thought of us.” Mansfield claims that Capitol had a hundred thousand pre-orders for the group’s new album before it was even finished.

Encouraged by Dylan, the group were breaking away and—as songwriters—learning to stand on their own feet. “I was there when Robbie realized he could write,” said Sally Grossman. “I’m sure Bob was an inspiration. Robbie thought, ‘Wait a minute, let me try.’ And he started writing those Americana songs.” Among the tracks released that summer as Music from Big Pink were two of the basement songs cowritten by Dylan. Featuring a mournful Richard Manuel melody—and a vocal worthy of his great influence Ray Charles—“Tears of Rage” unequivocally set out Dylan’s counterrevolutionary position,** while a thrusting version of the Dylan/Danko song “This Wheel’s on Fire” also made the cut. Arguably, though, the true flavor of the reborn group came through in the songs inspired by the rural backgrounds of Danko and Helm—“The Weight,” “We Can Talk,” and “Caledonia Mission.” “Levon and I have a powerful kinship,” Danko told me in 1995. “I grew up in southern Ontario; he grew up in Arkansas. He grew up in a cotton belt, and I grew up in a tobacco belt, and it was under similar situations—a farming community and those values. And we listened to similar blues and country music, so our influences were much the same.”

On Music from Big Pink a unique white-gospel country-funk style was patented and never successfully copied. “To us,” says Robbie Robertson, “Southern music that was white or black all got swirled in the same gumbo.” Big Pink was the sound of all the Hawks’ R&B and country influences filtered through Dylan’s poetics and expertly pieced together by John Simon. “John referred to it as ‘Robbie’s album’ and invited me down to the sessions,” says Al Kooper, who reviewed Big Pink for Rolling Stone. “I had no idea what was going to be on there, and then I heard it up at Albert’s and went, ‘Oh my God! Those guys did this?!’ Something had happened that I’d missed, and I think it was all that Woodstock stuff.”

From “Tears of Rage” to “I Shall Be Released”—another of Dylan’s basement songs—Music from Big Pink was about empathy and chemistry: five instinctively soulful players working together, their voices blending, their parts locking in time: “One voice for all, echoing around the hall,” as they sang on “We Can Talk.” Nothing smooth or slick: a gutty, gritty sound conjuring a funky backwater world. Sweet pining reverie and rollicking gospel from Richard Manuel, ribald Arkansas bravado from Levon Helm, feckless bemusement from Rick Danko; an afterthought, “The Weight,” which became the Band’s most famous song; one blasting, organ-churned rocker in “Chest Fever,” but mostly a deep spirit of fraternity and small-town oddness.**

“John Simon understood the recording console,” Robertson recalled of the sessions. “He asked us how we wanted the record to sound, and we told him, ‘Just like it did in the basement.’” Capitol was so delighted by what it heard that it flew the group out to L.A., where six more tracks were taped at the label’s eight-track studio in the basement of the Capitol tower in Hollywood. “All those tunes like ‘In a Station’ were so dreamy, instead of banging away like all the hard rock stuff at the time,” says guitarist Jim Weider. “It created a sound up here that really became the Woodstock sound.”

Rumors unsurprisingly spread that Dylan was playing on Music from Big Pink. Aside from his three songwriting credits, however, all he contributed to the album was the faux-naïf painting on the cover of Milton Glaser’s gatefold sleeve. More of a cultural signifier was Elliott Landy’s group portrait of the five band members with their families at Rick Danko’s brother’s farm in Simcoe, Ontario. “The idea of the picture was totally unusual to me,” Landy admits now. “Despite having a lot of relatives, my whole issue at the time was to separate from my family.” At a time when Jim Morrison was threatening to kill his father on “The End,” Big Pink’s sleeve honored the bonds of kith and kin.

The first people to sit up and pay attention to Big Pink were other musicians. When Eric Clapton obtained an acetate of the album, it ruined any pleasure he got from playing with Cream. “[It] came as a bit of a shock in 1968,” recalled Richard Thompson of Fairport Convention, which holed up in its own Hampshire version of Big Pink to work on 1969’s Liege and Lief. “It seemed to vault over the zeitgeist, back to purer roots—kind of counter-counterculture. The psychedelic bands were playing bits of blues and country, but the Band seemed to have real authority. . . . And they wore suits! And had short haircuts!” Three decades on, Big Pink still sounds wholly fresh and original. “Out of all the idle scheming,” Richard Manuel sang on his dreamy “In a Station,” “can’t we have something to feel?”**

Albert Grossman’s estimation of the Band suddenly skyrocketed. “I ran into him one night at the Tin Angel above the Bitter End,” recalls Artie Traum, who was himself managed by Grossman. “He had the cover of Big Pink in his hands, and he turned to me and—with his very pretentious way of speaking—said, ‘I’ve got the best group that ever lived, and this is it.’” At least a part of the reason for Grossman’s embrace of the group was the loss of Dylan’s trust in him—he needed new stars. “He hadn’t cared a thing about the Hawks,” says Michael Friedman. “When the Band became successful, all of a sudden he started looking at the balance sheet and decided Robbie was the way to go. He was an opportunist.”

Though Robertson was hardly the sole talent in the Band, Grossman chose to focus on him—just as Robertson focused on Grossman, frequently socializing with him in Bearsville. A street urchin at heart, Robertson was busy reinventing himself as a debonair man of the world and as Grossman’s new favorite son. “Albert could see that Robbie was probably the most driven and the least fucked-up of them, so he named him as band leader,” says Barbara O’Brien, who waitressed at Woodstock restaurant Deanie’s and later managed Levon Helm. “So he made a right move, looking at it from the outside.” The problem was, Grossman’s taking Robertson under his wing sowed seeds of distrust and disharmony within the group. “Nowadays I would so warn against that with a young band,” O’Brien says. “I would say you should incorporate and make sure it’s a partnership where everything gets shared equally.”

In contrast to Robertson, the other Band members hung loose in Woodstock. Helm and Danko, who’d moved out of Big Pink into a house off the Wittenberg Road, held court at the Espresso, wolf-whistling the hippie girls who drifted along Tinker Street.** “Most of us were single at that time,” Danko said. “It was a promiscuous kind of moment. People couldn’t get away with that these days, but it was a very good time to grow up in terms of history.”

Neither Danko nor Helm was overly impressed by the Grossmans; if anything, they had more time for local craftspeople. “Levon had more respect for carpenters—for getting your hands dirty and really working,” Barbara O’Brien says. “He was always uncomfortable with his celebrity status. He would say, ‘I’m just a farmer who loves to play music.’”

As it turned out, the Band was unable to capitalize on the rave reviews for Music from Big Pink. Before the album had even come out, Rick Danko broke his neck in one of the many accidents that he and his bandmates suffered over their years in Woodstock. “It was in the winter,” says Jonathan Taplin, then being lined up to road-manage the group’s first tour. “Rick had a big ‘Lincoln Confidential,’ as he called it, and he just ran it off the road. I’m sure he was drunk. He still had a very stiff neck in February of 1969.” Grossman must have cursed his bad luck: once again a road accident was going to cost him money. “It was the first time I ever saw anybody with those rigs that put spikes into your head,” says Happy Traum. “We saw a lot of Rick at that time, since he was courting Grace Seldner, who lived on the same street as we did.”

Meanwhile Garth Hudson and Richard Manuel were living on Spencer Road at the top of Ohayo Mountain. The rambling single-story house, built into rocks and belonging to concert promoter Sid Bernstein, offered dizzying views of the Ashokan Reservoir below. The large living room became a rehearsal space for the Band, while Hudson occupied one end of the house and Manuel inhabited the other with his girlfriend, Danish model Jane Kristiansen.

Just as Dylan’s Woodstock hibernation had enhanced his mystique, so the Band’s inability to tour enhanced theirs. When Al Aronowitz interviewed them during the hot and turbulent summer of ’68, he emphasized the back-to-nature flavor of their music and their adopted home. “Music From Big Pink is the kind of album that will have to open its own door to a new category,” he wrote, “and through that door it may very well be accompanied by all the reasons for the burgeoning rush toward country pop, by the exodus from the cities and the search for a calmer ethic, by the hunger for earth-grown wisdom and a redefined morality, by the thirst for simple touchstones and the natural law of trees.”

AS RIOTS RAGED and body bags came back from Vietnam, Dylan chilled out. “I met him in the loving stage, when he was existing to love and be loved by his family,” says Elliott Landy, who photographed the boyishly clean-shaven star for a Saturday Evening Post cover story by Aronowitz. “What he became afterwards I had no contact with, but when I saw him, he was experiencing stillness and quiet and love—what Woodstock was about. He was just a nice guy, very friendly, laughing.”

“Bob goes to bed every night by nine,” Dylan’s mother, Beattie Zimmerman, told writer Toby Thompson. “[He] gets up in the morning at six and reads until ten, while his mind is fresh. After that, the day varies; but never before. The kids are always around, climbing all over [his] shoulders and bouncing to the music. . . . They love the music, sleep right through the piano . . . and Jesse has his own harmonica, follows Bob in the woods with a little pad and pencil, jots things down. . . . These are the things Bob feels are important . . . and this is the way he’s chosen to live his life.”

Where at the start of the year he’d been phobic about being photographed, now Dylan permitted Landy to shoot him emptying the trash and sitting in his truck. Inside Hi Lo Ha he posed with Sara and their children, sitting at his piano in a seersucker jacket. It could almost have been the beautiful New Morning song “Sign on the Window” come to life: “Have a bunch of kids . . . that must be what it’s all about.” It’s possible Dylan even believed these sentiments or thought he’d found a way of assuaging his restlessness. “He’d like to be somewhere comfortable and I don’t know if that’s possible for someone with a mind like that,” Joan Baez told Anthony Scaduto. “I think he’s attempting that with his wife and children . . . [but] I can’t imagine him saying, ‘I’ve finally found peace.’” Asked in 2015 if it was painful to give up his art to protect his family, Dylan replied that it was “totally frustrating and painful” but that he “didn’t have a choice.” It was no coincidence that he was struggling to write songs, later referring to his painful creative block as an “amnesia” that hit him as he was out walking one winter’s morning.

When George Harrison visited Woodstock with his wife, Pattie Boyd, in late November 1968, he was astonished to find Dylan barely able to communicate.** Compounding the withdrawnness was Dylan’s grief at the sudden and unexpected death of his fifty-six-year-old father in June. It said much that Bernard Paturel could chauffeur Dylan all the way to Kennedy airport—to catch a flight back to the funeral in Minnesota—without even knowing that Abe Zimmerman had died.

Robbie Robertson had arranged for Harrison and Boyd to stay with the Grossmans, the Beatle’s visit prompted as much by Music from Big Pink as by Bob Dylan. “It was strange, because at the time Bob and Grossman were going through this fight, this crisis about managing him,” Harrison told Timothy White in 1987. “I would spend the day with Bob and the night with Grossman, and hear both sides of the battle.”

Disillusioned by the friction back home with his bandmates, Harrison heard in the Band’s album what his friend Eric Clapton did: a warmth, a spirit of brotherhood that offered freedom from the pitfalls of stardom. “George came to visit at a time when there were all these tensions with the Beatles in London,” says Jonathan Taplin. “I think he felt that the music being made in Woodstock was getting back to the roots of what he and Lennon had grown up with. And if you listen to Let It Be . . . Naked, it has the kind of simplicity that the Band had.”††

Harrison’s encounter with Dylan was painfully awkward. Dylan was on edge before Harrison and Boyd even arrived. “He came down to my studio and said they were coming,” Bruce Dorfman remembers. “I didn’t really care, but there was a whole thing about them coming to the house. From the gray box, you could sort of see some movement up on the road, and there clearly was a vehicle. Bob got himself all excited and said, ‘That must be George—he’s taken the wrong road.’ He was absolutely awestruck.”

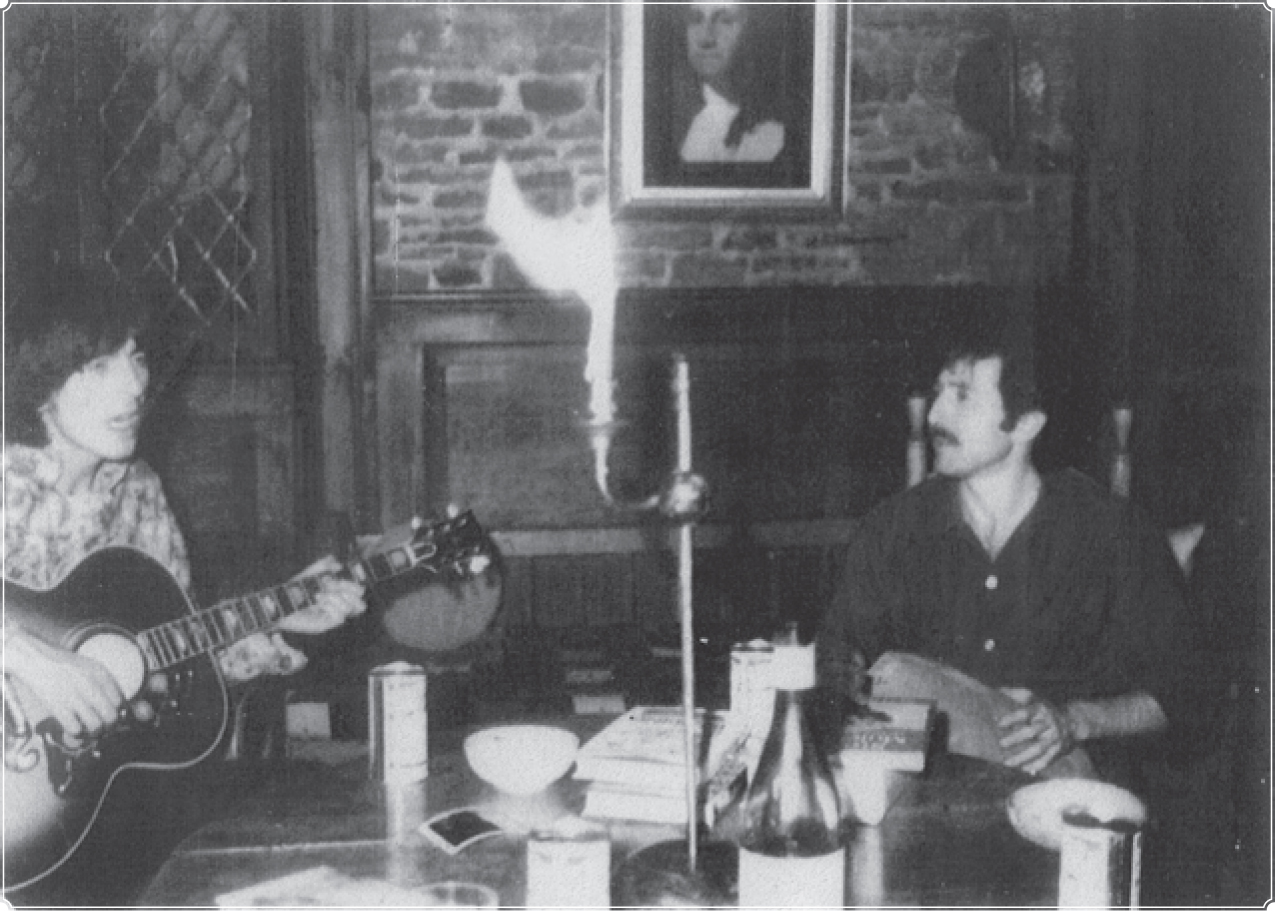

George Harrison with David Boyle, chez Albert Grossman, November 1968 (courtesy of David Boyle)

“Bob was an odd person,” Pattie Boyd recalled. “God, it was absolute agony. He just wouldn’t talk. He certainly had no social graces whatsoever. I don’t know whether it was because he was shy of George or what the story was, but it was agonizingly difficult. And Sara wasn’t much help, she had the babies to look after.” Ironically one of the two songs Harrison and Dylan managed to write together—on the third agonizing day at Hi Lo La—was a guileless plea for trust and intimacy called “I’d Have You Anytime.”

Things were easier when Harrison and Boyd came for Thanksgiving dinner at Hi Lo Ha, where they were joined by the Dorfmans, the Traums, Mason Hoffenberg, and others. Initially the atmosphere was stiff and formal, Dorfman becoming so irritated by the general sycophancy toward Dylan that he left. “Everybody was deferring to the master when they were out shooting hoops in the yard,” he says. “I became very annoyed and just walked away from it.” Later, says Happy Traum, “there was a knock at the door, and in walked five guys looking like they had just stepped out of a nineteenth-century daguerreotype.” It was the first time Traum had encountered the Band. “What totally broke the ice,” he says, “was when Richard Manuel sat down at the piano and the other guys gathered around for an impromptu rendition of ‘I Shall Be Released.’” Any lingering stiffness was dispelled by Hoffenberg’s suggestion of an orgy. “Let’s get all the boys over on that side and all the girls over on this side,” the coauthor of Candy yelled. “First couple to get their clothes off and screw wins.” History fails to record what happened next.

The host of the star-studded evening was slowly falling out of love with the Byrdcliffe house he’d bought three years before. Hippies were finding their way up to Hi Lo Ha, searching for the folk messiah who’d forsaken them. The Dylans often came home to find people in their swimming pool. Most were harmless, but some were scary. Fearing for the safety of his family, Dylan requested a personal hotline to Woodstock police chief Bill Waterous and even bought a Winchester rifle that he referred to as the Great Equalizer. “He had a very gutsy, confrontational side,” says Bruce Dorfman. “One time he asked me to come up to the house because he’d heard some noises in there. So we went in and roused a couple out of his and Sara’s bed. He went to get his gun, and it wasn’t a conversation.”

As he weathered the winter of 1968–1969, Dylan thought hard about two things: an album of country and western songs—to be recorded once again in Nashville—and a move to somewhere altogether less accessible than Hi Lo Ha.

![]()

* In 1997’s American Pastoral, which could almost be “Tears of Rage” in novel form, sometime Woodstocker Philip Roth wrote of his hero’s terrorist daughter that she “transports him out of the longed-for American pastoral and into everything that is its antithesis and its enemy, into the fury, the violence, and the desperation of the counterpastoral—into the indigenous American berserk.”

* The gospel influence on the Band was made even clearer by Garth Hudson’s 2014 account—in the Basement Tapes Complete box set—of the group listening to a bunch of late-fifties Savoy and Vee Jay singles owned by Hawks road manager Bill Avis. “There was a Caravans song called ‘To Whom Shall I Turn’ that Richard listened to over and over,” Hudson recalled. Equally influential on the group were the early recordings of the Staple Singers.

* One of the more unexpected tributes to Music from Big Pink was the appearance of its sleeve in the video for ABBA’s 1981 hit “One Of Us,” in which Agnetha Fältskog was seen unpacking and filing her record collection in her new, post-breakup apartment.

* The Wittenberg Road house, outside of which Elliott Landy took his famous Band shot for the inside sleeve of Music from Big Pink, is now—through a quirk of address-changing—on West Ohayo Mountain Road, a mere quarter-mile south of the Grossman pile in Bearsville. For a wonderfully convoluted account of how the house came to be identified, see Bob Egan, “The Band,” Pop Spots, http://www.popspotsnyc.com/the_band.

* The late Bob Johnston had a similar experience when he came to Hi Lo Ha. “My old lady Joey and Sara talked for a couple of hours while Bob and I sat and watched the fire,” Johnston said. “He never said a word, and neither did I.”

† In 1993, when Viking Press solicited an endorsement of my Band biography Across the Great Divide, Harrison sent back this generous line: “They were the best band in the history of the universe.” Quite a statement for an ex-Beatle.