“YOU DIDN’T TALK about God, and you didn’t talk about Albert,” says Elliott Landy, who photographed many of Grossman’s biggest clients. “Either you believed in him or you didn’t.”

It was difficult not to believe in Grossman, who had built his power base on the backs of his folk superstars but was now moving firmly into the sphere of electric rock. By 1967 he was as much of a legend in his own right as any manager had been. “Even more than Colonel Tom Parker, he was larger than life,” says Danny Goldberg. “He had two reputations. One was that he knew what artists were worth and would fight for their right to be weird. The other was that he had personally made a lot of money and maybe was a little tricky in the way he made it. When I got to know him, he was clearly somebody who had a sense of his own mythology and milked it at all times.”

It was as if Grossman had become the very person people thought he was. When they interpreted his long silences as power plays, he decided that that was what they would be. “Only a fool would not smile back at Albert Grossman,” Warner Brothers executive Carl Scott said of him many years later. The Grossman that Dylan fans saw in Don’t Look Back—gruff and bullying when he needed to be—was as useful a persona as any employed by Dylan himself. “He was one of the first managers to create his own brand,” says Paula Batson, who worked for him in the early seventies. “You think of the long hair with the ponytail, his demeanor of being so cool and aloof. That was really something new, that a manager would attain that kind of power.”

The long hair in a ponytail—held in place by a twist of wire—was key to Grossman’s persona. As much as he liked to make money, he preferred looking hip to looking rich. One night in New York he was eating in an expensive restaurant with Robbie Robertson, John Simon, and Jonathan Taplin when a middle-aged woman approached the table and began bawling “God Bless America” at the top of her lungs. “Those kinds of things would happen everywhere you went,” says Michael Friedman. “Just walking down Park Avenue with Albert was a trip.”

That the ponytail persona was deceptive was irrelevant to Grossman. He paid lip service to radical politics, but more important was not being mistaken for a typical businessman. “Albert would never venture a political opinion, because (a) it might not be hip and (b) it might be proven wrong,” says Peter Coyote, who came to Woodstock at Grossman’s invitation with Emmett Grogan, cofounder with Coyote of radical San Francisco street troupe the Diggers. “Emmett and I frightened him and attracted him. He was an older guy dealing in a business populated by young kids who were changing the social structure incredibly rapidly. They knew they were making bargains with the devil, but this particular face of the devil had a ponytail and ate organic food.”** For Grossman hipness was everything, though it often meant belittling lesser mortals. “He had that imposing countenance and all his little quirks,” says Paul Fishkin. “But I also discovered that he was a very flawed character. He was not a nice person in a lot of ways, and a lot of people hated him because as his power grew, he abused it.”

“I know people that were long-time friends of Albert’s who said they wouldn’t want to be on the other side of a negotiating table from him,” says John Byrne Cooke, who became one of Grossman’s stable of road managers. “Because when you walked out on the street, you would realize you didn’t have your pants on anymore.” Bob Dylan still had his pants on, but his rupture with Grossman was now common knowledge. “Albert’s basic thing was, ‘If you’re going to sign a contract, maybe you should read it,’” says Jim Rooney. “He taught a lot of his artists that this was a business and you’d better look out for yourself. And I think Dylan came to that realization.” If people knew about the Dylan rupture, Grossman kept schtum about it, knowing it could only be bad PR. “Albert never even mentioned it to me,” says Linda Wortman, who filed copyrights for him at Fourth Floor Music. “It was just a fait accompli: Albert was midtown, and Bob was downtown. It was two separate places, two separate things.” Eventually Naomi Saltzman poached Wortman herself from Grossman: “She set up Big Sky Music and hired me to run it out of her apartment. There was an air of paranoia about it: nobody should find out that I was working for Dylan.”

Other things were changing in the Grossman office. By the end of 1969, both John Court and Bert Block were gone. “Something happened between John and Albert, and it must have been about money,” says Norma Cross. Having overseen albums by such artists as Gordon Lightfoot, Richie Havens, the Electric Flag, and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Court left to pursue his career as a producer. “He was a great guy, very simpatico,” says Warren Bernhardt, who played in Court-produced jazz-blues band Jeremy & the Satyrs. “He was always fun to work with, and he bought a big house up near Palenville.” Keith Reid visited Court’s Palenville mansion with then-girlfriend Nico. “It was the first time I’d ever seen a bucket of cocaine,” he says. (Nico also took Reid to meet Tim Hardin, who never even made it out of his bedroom to say hello.)

Bert Block’s old-school sensibility, meanwhile, no longer chimed with Grossman’s hipness. “I liked him, but it was an odd mix for him to be with Albert,” says John Byrne Cooke. Michael Friedman, who later worked with Block when he managed Kris Kristofferson, recalls him as “a Friar’s Club type who wasn’t a clever eccentric guy like Albert and didn’t really care about the music that was coming out of the office.” With Block gone, it was down to twenty-five-year-old Friedman to keep the show going. “I was in over my head,” he says. “But because I was there, Albert felt he could spend more time in Bearsville, which was really where he wanted to be.”

Into the breach stepped a new partner, Bennett Glotzer, who was younger and more ambitious and came into the company as part of a package with his brother-in-law Bobby Schuster. He also brought with him his own acts Seatrain, Rhinoceros, and Blood, Sweat & Tears. “Bennett didn’t have the poetic hippie mystique that Albert had,” says Danny Goldberg. Grossman’s friend Ronnie Lyons recalls Glotzer as “a real douchebag” who was despised by the Band when he occasionally showed up at their concerts.

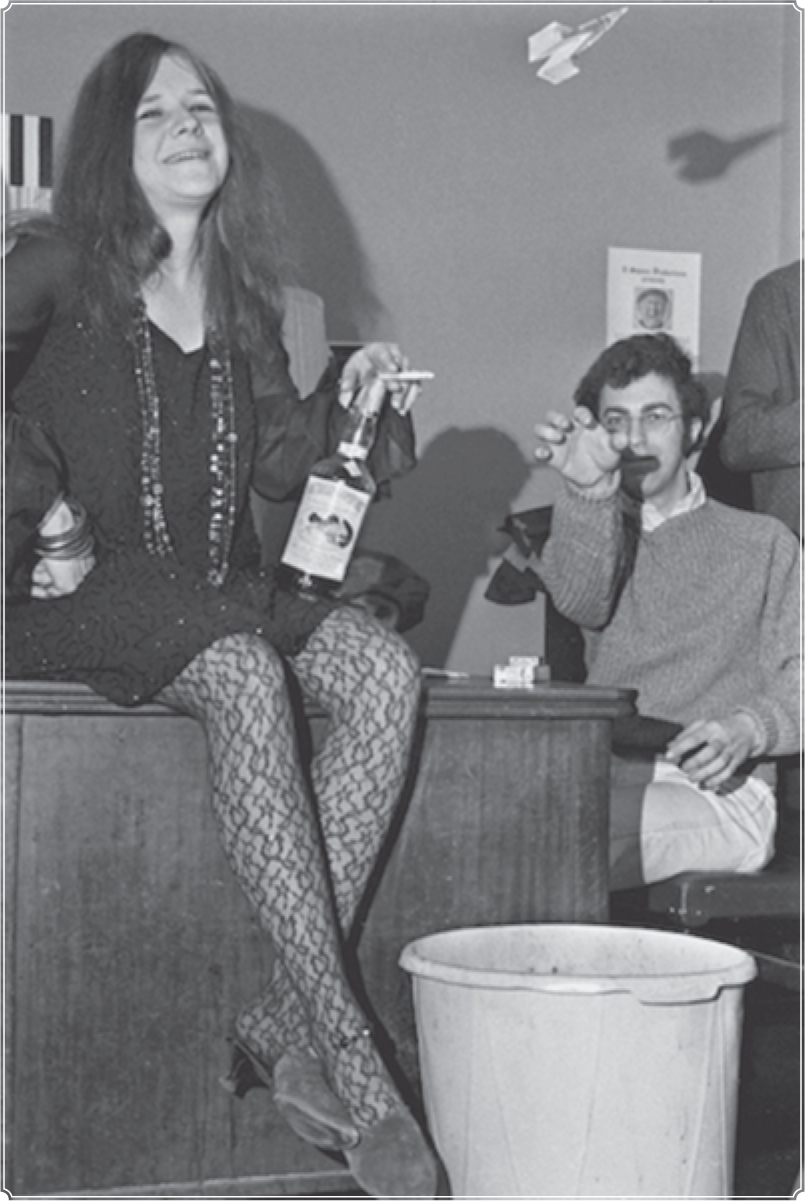

A key reason Grossman partnered with Glotzer was his legal background, which proved useful during the negotiations to sign Grossman’s hottest new act to Columbia Records. That act was Big Brother & the Holding Company, a San Francisco band fronted by singer Janis Joplin. Grossman had seen them play in June 1967 at the Monterey Pop Festival, where Joplin’s bloodcurdling rasp of a voice so stunned the crowd that Big Brother were asked to perform a second set the following day. She was pockmarked and bacchanalian, a wild child who’d fled her native Texas to become a queen of the hippie scene in San Francisco. She was clever and funny but also deeply insecure, alcoholic, and nymphomaniac, keen to live the white-negro blues life she sang about. The Big Brother musicians were stoned and clunky, but when Joplin let rip with the howling pain of Big Mama Thornton’s “Ball and Chain,” it didn’t matter.

“This was pretty much the end of Peter, Paul & Mary and Odetta, all those early folk singers,” says Michael Friedman. “And I think Albert found this a strange world: he wasn’t really into rock and roll at all.” Yet Grossman was quietly mesmerized by Joplin, who seemed to hold the counterculture in the palm of her hand. At Monterey he was one of a cluster of powerful managers and record executives who understood that the festival was really a rock trade show masquerading as a hippie love-in. “We all thought it was great that the Grateful Dead got signed by Warner Brothers,” says John Byrne Cooke. “But when you look at the effect of this over time, it was like [the record companies] co-opted the counterculture.” The Dead’s manager, Rock Scully, watched Grossman “trying to snag Janis and . . . doing it in the most ruthless, shabby way, dangling Bob Dylan, whom [she] adores, right in front of her eyes.” At the back of Grossman’s mind as he watched her was his need for a new solo star to replace Dylan, yet he also had to tread carefully and not show his hand too early (especially since Big Brother already had a manager). “The paranoia about being ripped off was universal in the San Francisco community,” says John Byrne Cooke. “Which was why everyone believed you shouldn’t do business with ‘those people in New York and L.A.’” As word filtered through to the group that Grossman was interested in them, Joplin felt the same ambivalence the Dead had felt: she wanted to be a star, but she also wanted to be true to the hippie cause.

In Buried Alive, her 1973 biography of Joplin, Grossman’s in-house publicist Myra Friedman defended him even as she captured his mix of ruthless scheming and vulnerable shyness. “The most well-founded charge against [him],” she wrote, “is a tendency to become overly involved with the tomato patches in back of his Woodstock home.” In the end, the overture came from Joplin to Grossman, who flew to San Francisco to meet Big Brother in November 1967. According to Friedman, Grossman told the band he could get them a generous deal and laid down only one condition, that they eschew the use of heroin. Joplin, who’d already dabbled in it, assumed her most innocent look and agreed wholeheartedly that smack was a very bad thing.

In February 1968, the group flew to New York to sign their contract with Grossman and perform at Bill Graham’s Fillmore East. According to John Byrne Cooke, Grossman had already made a deal worth $250,000 with Columbia’s Clive Davis, who had himself witnessed the Joplin phenomenon at Monterey. Grossman also hired John Simon, hot off Music from Big Pink, to produce their first album. “Albert had been working with John Court, but that was falling apart,” Simon says. “I remember walking on the street in New York with him, and he said, ‘I’ll scratch your back, and you’ll scratch my back.’ Which turned into, ‘You’ll scratch my back, and I’ll scratch my back.’ But it was good for me to be affiliated with him.”

As it turned out, Simon wasn’t a good fit for Big Brother. Having worked with the Band, he was unimpressed by the sloppiness of Big Brother’s playing. Though Columbia had agreed that a live album would best represent the raw energy of the group’s sound, Simon insisted on overdubs to make their performances sound more competent. “He didn’t reach out to Big Brother in a way that made them feel appreciated,” says John Byrne Cooke, by now the band’s road manager. “They never really established a lot of communication.”** From the viewpoint of the group’s lead guitarist Sam Andrew, Simon’s secret dream was to be a member of the Band: “They were wonderful players, really tight. And then he comes into this insane group of Californians, who are playing these jangly, out-of-tune guitars.”

Janis Joplin with John Simon at Columbia’s studios in New York, spring 1968 (Elliott Landy)

“Janis and I were both young, and I was impatient with her,” Simon admits. “Meanwhile she saw me as Mr. Smarty Pants who didn’t get what they were doing.” He was especially turned off by what he heard as the studiedness of her shrieking. “She’d go, ‘How about this scream?’” he says. “She’d say, ‘Tina Turner does this,’ or ‘Mama Thornton does it this way.’ It was just too ersatz and calculated for me.” Cheap Thrills was powerful nonetheless, a kind of acid-soul album that sounded like Etta James fronting Jefferson Airplane. On “Ball and Chain” and Erma Franklin’s “Piece of My Heart,” Joplin was an R. Crumb hippie chick wracked by heartbreak. “I’ve come to appreciate her more than I did then,” Simon says. “I mean, she was more important sociologically than she was musically, but her actual talent gets overshadowed.”

Though Simon had witnessed how close Grossman was to Robbie Robertson, he realized the relationship with Joplin was closer still. If Dylan was the favorite son who’d rebelled and left home, Joplin was Grossman’s new favorite daughter—especially after Cheap Thrills climbed to number 1 on the album chart. “Janis loved Albert,” says Simon. “I don’t know what her situation was with her own father, but Albert was such a father figure to her.”

While Joplin kept her home base in Northern California, she often visited Grossman in Bearsville. So close did they become that some wondered if the relationship had gone beyond a surrogate father-daughter dynamic.

GROSSMAN’S CLOSE ATTENTION to Joplin had the indirect effect of making his other acts jealous. “All good managers develop a wagon circle,” says Ed Sanders, a friend of Joplin’s. “When Janis calls in the middle of the night with a complaint, you pick up the phone. Somebody else calls, you don’t answer.” Peter, Paul & Mary, who’d made him his first million dollars, were unhappy enough with Grossman’s neglect of them to leave his stable in 1970. “Peter Yarrow told me, ‘Albert’s wearing too many hats,’” says Ronnie Lyons. Odetta, who went even further back with him, felt so “betrayed” that “at one point in my life I could not hear [Grossman’s] name without the hairs on my back standing up.”

Another act hurt by the lack of attention was Ian & Sylvia. “Ian Tyson was a tough guy, but he felt that Albert had stopped caring,” says Michael Friedman, who went on the road with the duo. “The people Albert was really concentrating on were the Band and Janis. The problem was that Albert had signed all these artists but didn’t have enough staff to service them.” About the only act that didn’t scream and yell when he couldn’t reach Grossman was Gordon Lightfoot. “Nobody put anything over on Gordon,” says John Simon, who’d produced his 1967 album Did She Mention My Name. “It wasn’t like Albert was his Big Daddy like he was to Janis and other acts, because Gordon didn’t need that.” Two years later, Grossman negotiated a Warner-Reprise deal for Lightfoot worth over $1 million; by early 1971 the Canadian folk star was in the US top 5 with “If You Could Read My Mind,” the first of four top 10 hits he chalked up in the seventies. “That put him in a whole other category,” John Court recalled. “Gord hasn’t been hungry since.”

On the publishing side there was residual Dylan business, but most of the effort was now expended on songs by the Band, primarily those by Robbie Robertson. “That was the big thing,” says Danny Goldberg, who worked for Sam Gordon, Grossman’s head of publishing. “Otherwise it was just me trying unsuccessfully to get people to cover Ian Tyson songs.” A month after starting at Fourth Floor Music, Goldberg was summoned to Grossman’s office, where his new boss peered out from behind his vast desk and asked which songwriters he’d been focusing on. When Goldberg nervously mentioned the Australian writer Gary Shearston, Grossman groaned. “He looked at me with great disgust,” Goldberg recalls. “He said, ‘You know, I just can’t care about an artist’s career more than they do.’ It had the effect of making me feel incredibly small. But that line? Forty years later I quote it all the time.”

The line expressed the enervation Grossman was feeling after a decade of artist management. “John Court said to me, ‘Albert is getting tired of doing this,’” says Dean Schambach. “‘But he’s so good at it.’” Years later, Sally Grossman said that her husband was “burned out” by this point and “couldn’t wait to get out” of management. As the sixties neared their end, Grossman’s tomato patches began to look more alluring than his demanding artists. Ian Kimmet, who chaperoned Janis Joplin around London in the spring of 1969, was once on a plane with Grossman when the Cumulus Nimbus turned to him and said, “Ian, I would never manage anybody again unless it was fifty-fifty. I was continually bringing things to Bob and I would set them up for him and he would change his mind.” Michael Friedman thinks Grossman had come to believe that he was responsible for his artists’ success: “He thought that without him they would have had nothing. And maybe that’s true. But then without them he would have had nothing.”

One act that Grossman did not regret taking on was the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, whose progress he had followed from their early days on the Cambridge folk scene. He particularly enjoyed the company of Geoff and Maria Muldaur, who’d played in the group together since marrying in late 1964. “They were very witty and sarcastic,” says Jonathan Taplin, who’d roadied for the Kweskin band at Newport in 1965. “They were steeped in the jazz and blues of the twenties and thirties, and a lot of the music they played came out of that world.”

Geoff Muldaur had made two folk-blues albums with Paul Rothchild at Prestige, while Maria had sung with John Sebastian in the Even Dozen Jug Band in Greenwich Village. In the Kweskin band they were managed by folk doyen Manny Greenhill and signed to Vanguard Records. One night at Dick Fariña’s apartment, Geoff spotted Grossman across the room and pushed Jim Kweskin toward him. “I said, ‘Go ask him to be our manager,’” Muldaur says. “He said, ‘He won’t wanna be our manager!’ I said, ‘Go ask him!’ So he asked, and Albert said yeah. It did change the band a little bit. We started dressing differently. But I resisted all that kind of showbiz stuff, so I probably wasn’t best equipped to ‘jump on the escalator,’ as Albert used to put it.”

The first thing Grossman did was get the Kweskin Band off Vanguard and onto Reprise, the Warner Brothers label—founded by Frank Sinatra—that was now home to all that was hip in Los Angeles. “Frank’s name was still in the parking lot on the curb,” says Geoff, “but they were picking up all these young hip artists who would talk about other young hip artists.” The group’s first Reprise album was 1967’s Garden of Joy, their lineup by now bolstered by violin player Richard Greene and banjo maestro Bill Keith. “It was a big change for them to become part of Albert’s group of artists,” says Jim Rooney, who’d booked them at Club 47. “Before that, they were a fairly raffish, ragtag group of people who liked to travel around in a Volkswagen bus. People started to think, ‘Gee, maybe we could do a little bit better if we had someone like Albert managing us.’”

The Kweskin Jug Band making their Reprise debut in 1967

The Muldaurs were soon invited to stay in Bearsville, where—like Robbie Robertson before them—they were swiftly initiated into the finer things in life. “Albert had quite a bit of money by then,” says Maria. “He and Sally would pore over hundreds of colored sheets in order to find exactly which shade of pale cantaloupe they were going to paint the bedroom. These days you’d call Albert a foodie. He built a greenhouse because he wanted to grow organic vegetables. So this tough guy from the heart of Chicago turned into quite the country gentleman.”

“You couldn’t know Albert without knowing his house,” says John Simon. “It was the nexus of the Woodstock scene, and you weren’t really accepted until you were invited there. And within the house was a room that was the center of the center. That was the dope room, the drug room, which was where all the funny stories and the giggling went on.”

By late 1969 the Kweskin Jug Band was no more, its titular leader having gone off to join the Fort Hill Community, founded by the group’s former member Mel Lyman. “It was like a cult, like Charlie Manson,” Al Aronowitz said of Lyman’s “family.” “Not that he did anything violent, but Mel certainly had his people brainwashed.” Parting ways with Kweskin, the Muldaurs became a duo act with Grossman’s help and started work on their own Reprise album, Pottery Pie. “By the time Albert had Janis, we saw the possibility of our music being accepted by much larger audiences,” says Maria. “There was big commercial stuff starting to happen. But it was still very rootsy.”

Validating the rootsiness of all Grossman’s acts was the Band, which finally got to perform live after Rick Danko recovered from his broken neck in early 1969. “They’d been a backing group for so long,” says John Simon. “All of a sudden they got the chance to be a band in the forefront. It happened really quickly, and there they were on the cover of Time magazine.”

Promoter Bill Graham heard about the “mythical group of guys that lived up in the country and woodshedded,” falling so heavily for what he called their “funky, groovy, swirly” sound that he made his own pilgrimage to Woodstock to plead with them to play live. By the time the Band made their nervous Winterland debut for him in April 1969, they had finished work on their second album. Recorded not on the East Coast but in a sound-baffled pool house in West Hollywood, The Band took the lo-fi elements of Music from Big Pink to a logical extreme: it sounded like rock and roll made in the nineteenth century.

“Everything in rock was kind of going in that high-end direction,” Robbie Robertson said. “We wanted something different, a kind of woody, thuddy sound.” Much of the flavor came from the South, or rather from Robertson’s filtering of Levon Helm’s Southern background. On “Rag Mama Rag” and “Up on Cripple Creek,” Helm was bawdy and knowing; on the Civil War swan song “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” he was mournful and indignant. “It was like these guys had come from 1878 or something,” says Robbie Dupree, for whom the Band were the main lure that took him upstate. “It was so different and so counter. Southern life was something not revered in America at all, because of all the associations that Northern people had with the lynchings and the beatings. So to meet people who seemed like they came from there, there was nothing like it.”

“To me they were the next most influential band after the Beatles,” says Larry Campbell, Levon Helm’s right-hand man in his last years in Woodstock. “They were taking everything that said ‘America’ musically and inventing this thing that hadn’t existed before. There was so much talk about that record, and then the talk turned to this place in upstate New York where these guys were living and where this scene was going on.” Indeed, The Band spoke not just of the South but of Woodstock itself. As the autumn leaves reddened on Overlook’s maple trees, Robertson wrote the farmer’s plaint “King Harvest (Will Surely Come).” “It was a time of year when Woodstock was very impressive,” he recalled. “It just made you realize that this was the culmination of the year for so many people.” Meanwhile “Oley” in “When You Awake” was a guy who worked at the Houst general store in Woodstock, and “Unfaithful Servant” was inspired by a couple who’d worked for Albert Grossman and been fired for stealing from him.

As much as the music itself—earthy, gritty, exultant, sorrowful—what the Band represented was a kind of benign gang. “It was a great bunch of brothers,” says Garth Hudson, whose keyboard countermelodies elevated the Band’s sound to a higher musical plane. “The respect was always there. We tried to make the track fit the words and the voices. I never used a sound that was close in harmonic structure to someone’s voice.” For Al Kooper, “Garth was obviously so far ahead of all of us musically. . . . The way Bob was Shakespeare compared to all the other songwriters, Garth was the Shakespeare of the organ.”

“I started thinking that the music was finally taking shape with the second album,” Levon Helm told me. “We had actually figured out some methods of how to really turn the heat up and get the music to cook: how to blend our voices three different ways, how to get the track together and not make it so complicated.” It helped that the Band’s members were all settling into more or less monogamous relationships in Woodstock: Rick Danko with Grace Seldner, Richard Manuel with Jane Kristiansen, Robbie and Dominique Robertson with their newborn daughter, Alexandra. Even the introverted Hudson had hooked up with a dark-haired beauty named Suzette Green. “She was drop-dead gorgeous,” says Geoff Muldaur. “Levon would tell her, ‘Y’oughta come over to our place tonight—we’re havin’ a party.’ But none of them got near her except Garth.”

To John Simon, the Robertsons were one of the few couples in Woodstock who stayed faithful to each other. “I mean, everybody was fucking everybody else,” he says. “You could tell who was fucking whom by what car was in what driveway. It was all pretty open, but Robbie and Dominique were a real solid couple. And then Rick married Gracie, and Richard married Jane.” Rather fierier was the hookup between Levon Helm and Libby Titus, the Woodstock-born wife of Barry Titus, grandson of cosmetics magnate Helena Rubinstein. Titus was a well-read bohemian who’d dropped out of nearby Bard College in 1965 and moved to Greenwich Village, where she became pregnant with Barry’s son Ezra. Under the aegis of Albert Grossman, she had also released a self-titled album of songs by writers such as Tim Hardin, the Beatles, and the Lovin’ Spoonful. “Libby was like a cross between Joan Didion and Fran Drescher,” says Peter Coyote. “She was gorgeous; she was louche; she was languorous. I don’t know how she got Levon, because there could not have been two more disparate souls on the planet.”

The 1968 debut album by Levon Helm’s future common-law wife

According to the scurrilous Mason Hoffenberg, Titus “got” Helm in the spring of 1969 because she’d set her sights on the Band, whom she later described as “the most seductive young men I’d ever met.” “One night,” Hoffenberg recalled in 1972, “Rick and Levon are coming over to my house to get her at about a hundred miles an hour, and Rick had his big accident, broke his neck. So Levon got her.” After she and Ezra moved into the Wittenberg Road house in early 1970—Danko having moved east to Zena Road—Titus became “obsessed” with Helm and “very isolated,” thanks to the jealousy that made him reluctant to show her off in front of other men.

“They were oil and water,” says Jonathan Taplin, who by now was road-managing the Band. “But there was obviously a sexual attraction there, and they were very funny together. Libby and Maria Muldaur both had the same sarcastic sense of humor and could drop the bon mot that would just devastate you.” The Dorothy Parker of Tinker Street, Titus decided to make the best of it in the Helm shack. “It could have been in Arkansas,” says Taplin. “There were dogs out on the porch, a couple of cars that didn’t work anymore, a huge fireplace that he kept going all winter long. Libby found it rather amusing and refused to dress like a country girl. She wore her silk dresses and high-heeled boots. She wasn’t going to go down-market and wear a pair of Levi’s.”

The dogs were named Light and Brown—possibly drug references—and were the joys of Helm’s life. “They’d follow when [he] took me for rides through the woods,” Ezra Titus later wrote of his life in the Helm homestead. “We’d go far enough away from the house so that my mom couldn’t hear and he’d break out some firecrackers. We’d shoot a few bottle rockets and blow up tin cans. When my mom went out, Levon would let me bring the dogs inside which, to me, was like a party.” In December 1970, five-year-old Ezra found himself with a new half sister, Amy. “Levon was just salt-of-the-earth, right from the soil of Arkansas,” says Maria Muldaur. “While people like Libby were floating around putting on airs, he’d bring Ezra and Amy over to play with Jenni.”**

If there was a blot on the Band’s landscape at this time, it was the niggling anxiety over Richard Manuel’s drinking. “He was the most deeply sensitive of the lot of them,” says Jeremy Wilber, who witnessed Manuel’s alcohol consumption almost nightly from behind the bar of the Sled Hill Café. “I think he would have had so much happier a life if he’d been the piano player in a whorehouse. He could drink and drink and drink and drink, and it never changed his personality.” Manuel’s favorite tipple was a cocktail that he and Rick Danko called “the Go Faster”: two hits of vodka, one hit of cherry brandy, topped off by 7 Up.

As their profile rose, the Band’s relationship with Grossman changed. Given their long association with Dylan, it was a delicate transition to navigate. “Some of the other guys in the Band didn’t appreciate Albert as much as I did,” Robertson recalled. “But I thought he was a great teacher of things. . . . He kind of took me under his wing and I became pretty close to him in those days.” For his part, Danko “always got along with Albert. . . . If it hadn’t been for him, I might have had to get a serious job.”

“Rick kind of admired Albert,” Jonathan Taplin confirms. “Levon was very on and off with him: sometimes he hated him, sometimes he liked him. Garth was distant, as Garth was to a lot of people. The closeness was with Robbie, who lived next door to Albert and shared intellectual interests. But there wasn’t closeness with the rest of the Band, because they were really kind of country guys.”

If Grossman shared “intellectual interests” with Robertson—as he did with Janis Joplin and others—ironically with each passing year he was becoming more of a “country guy” himself. Increasingly Bearsville provided escape from the frenzied pressures of the industry. Even Joplin found it hard to track him down there sometimes. “Everybody was looking for attention, and nobody was getting it,” says Michael Friedman.

For Ronnie Lyons, a frequent guest of the Grossmans, there was a feature of the Bearsville estate that summed up his old friend’s attitude to the music industry. “It was a building that looked like a garage, but it was not a garage,” Lyons remembers. “It was called the Car Wash. And if anybody came up that Albert didn’t want to see, he’d go into the Car Wash, open the electric door, and drive straight out the other side.”

![]()

* To his credit, Grossman did bankroll Howard Alk’s 1971 documentary about the police killing of Black Panther Fred Hampton. “That man’s got to be heard,” he told Alk.

* Something of Simon’s exasperation can be detected in the Columbia studio footage shot by Donn Pennebaker and included in Howard Alk’s 1975 documentary Janis.

* In July 2009, after writing several short pieces about dysfunctional teenage life in the Woodstock of the seventies and eighties, forty-three-year-old Ezra Titus took his own life in Florida. “Though his relationship with Libby was tumultuous,” wrote her husband, Donald Fagen, “Ezra and his mother were so close that it seemed at times as if they shared a single soul.”