BY THE TIME Joni Mitchell got to Woodstock, we were about thirty thousand strong. It was August 15, 1998, and the composer of “Woodstock”—who’d famously missed the original festival—was playing the second Day in the Garden at Bethel, sandwiched between Lou Reed and headliner Pete Townshend.

There were no campsites this time, but there were a lot more porta potties. Baby boomers had paid $70 to get in rather than break through chain-link fences. I’d driven the back roads of Sullivan County in the morning without hitting a single traffic jam. More surreally I found myself roped into a Radio Woodstock panel discussion of the 1969 festival’s legacy with Richie Havens—who’d kick-started the original gathering almost exactly twenty-nine years earlier—and an ectomorphic figure dressed in black. You might ask what Joey Ramone was doing there, since punk rock’s brief had surely been to destroy everything the “Woodstock Nation” stood for. But then you’d also be entitled to ask what Lou Reed was doing there, since no one hated hippies more than he did. At least Pete Townshend had been there in ’69.

A Day in the Garden was a restrained and civilized affair. Nobody was freaking out on brown acid or splashing naked in the lake behind the stage. Nearly three decades after dairy farmer Max Yasgur opened his floodgates to over 350,000 unkempt longhairs—no one has ever been sure of the exact number, which may have reached Joni’s fabled half million—we were all so inured to the corporate business of rock fests that it was hard to imagine the tribal excitement (or trepidation) people felt as they swarmed toward Bethel in search of some heady communal climax to the sixties dream.

The Woodstock Music & Art Fair remains the defining congregation of rock’s sixty-year lifespan, with “Woodstock” now a byword for all collective celebration and ersatz Dionysia. Woodstock was where the overheated rhetoric and psychoactive disturbance of the sixties hit critical mass. Watching Michael Wadleigh’s great documentary Woodstock is like watching footage from a war zone: helicopters and medical tents, young men dazed and confused, muddy chaos. Vietnam hangs over the event like a shroud, permeating everything from the mess call that follows Wavy Gravy’s famous breakfast invitation to Hendrix’s closing de(con)struction of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” One of the most significant interviews in the whole film is with a jovial porta potty guy who had one son in ’Nam and another at the festival.

So were the half million really “stardust” and “golden,” in Mitchell’s lovely lyric, or were they hallucinating survivors of a middle-class disaster zone? Wadleigh’s film—with camerawork by a young Martin Scorsese, among others—suggests the truth lay somewhere in between. Early intimations of the hoards advancing on O Little Town of Bethel had Bill Graham exclaiming that “there must be some way of stopping this influx of humanity,” but no one—neither the bellicose Graham nor baby-faced hippie impresario Michael Lang—knew how to do it. “It looks like some biblical, epical, unbelievable scene,” gasped the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia before Richie Havens had even been pushed out on the stage like some berobed African chieftain about to be sacrificed.

As the threadbare remnants of the “ripped army of mud people”—Robbie Robertson’s phrase—finally dispersed late on Monday morning, there was no clear sense of what the festival even meant. “Drugs and revolution, now it’s all a little contrived,” said one of the less fried hippies interviewed for the film. “People are really looking for some kind of answer when there isn’t one.”

FORTY-FOUR YEARS AFTER he first rode around the festival site on his BSA motorcycle, Michael Lang sits in a restaurant on Tinker Street and talks of the complicated relationship between Woodstock and “Woodstock.” Like everyone around here, he knows how much the town owes to the festival that took place over sixty miles southwest of where we’re sitting. And he knows there’s a good and a bad side to that debt. The good side is all the tourists who pour into town and spend their hard-earned dollars on tie-dyed T-shirts and hippie knickknacks. The bad side is all the tourists who pour into town and . . .

Well, you get the point.

Over the many years since 1969, Woodstock has become a kind of themed village of sixties hippie life, the culmination of the pop-cultural nightmare that Bob Dylan dreaded it would be. Where once the invaders came to seek him, now they descend on dinky Tinker Street to find the fields where Lang’s festival happened—only to learn that it didn’t happen there at all. “I used to sit on the back porch of Radio Woodstock on a summer afternoon,” says Stan Beinstein, the station’s former general manager, “and somebody would always walk up and ask in a German accent, ‘Excuse me, vere vas de concert?’ Constantly, constantly. Some people lied and directed them to the Andy Lee baseball field. Or they’d tell them the truth: ‘Well, it’s about a sixty-five-mile drive; take you about an hour and a half.’”

So why did Lang call it Woodstock? The short answer is that Dylan lived there, and that Music from Big Pink was born if not recorded there. The longer answer begins with the fact that Lang, a nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn, had first come to the town as a kid. “My mother liked the art galleries, so we’d come through Woodstock on the way back from visiting relatives in Canada,” he says. He returned to the Catskills after running a head shop in similarly hippiefied Coconut Grove and—in May 1968—promoting the first Miami Pop Festival. “When it was time to get out and move back north, I decided I’d like to live in that kind of community but somewhere nearer the city,” he says. “So Woodstock was a natural place to come. The Band was in town, and I met those guys early on.” He was all too aware of Albert Grossman as “the eye of the music storm that descended on Woodstock.”

Moving with his girlfriend to a converted barn on Chestnut Hill Road, Lang began familiarizing himself with the local music scene. He also learned about the history of the area, going all the way back to Hervey White’s Maverick festivals. “There will be a village that will stand for but a day,” White had written in a festival flyer in 1915, “which mad artists have hung with glorious banners and blazoned in the entrance through the woods.” When Lang experienced the Sound-Outs on Pan Copeland’s farm, their “joyous, healing feel” conjured visions of something on a far grander scale. And that something was encapsulated by the town of Woodstock itself. “The spirit of the festival was embodied in the people that lived there,” Lang’s friend Alan Gordon told writer Steve Turner. “Woodstock had become the Jerusalem of the new consciousness. There were people out here living in teepees and domes. Tie-dye stores started opening in 1966. Alternative food stores started here.”

Gordon remembered Lang laying out maps of potential festival sites at Jim and Jean Young’s shop the Juggler on Tinker Street. Jim dabbled in local real estate and took Lang to see the Winston Farm off Route 212 near Saugerties. “It was scheduled to become a golf course,” says Lang, “but it didn’t work.” He adds that he “never found a piece of land around town that did work.” The belief that he was “booted out of Woodstock” by the town board is, he says, a misconception.

It is true that by the early summer of 1969 Woodstock was all but overrun by barefoot children of the counterculture. “At the weekends there was always an influx of hippies coming in,” says Keith Reid. “There were people on the village green with acoustic guitars, and lots of pretty girls.” The presence of these back-to-the-land dropouts was now seriously unsettling longtime residents in ways that not even the Maverick revelers had done a half century earlier. “The town was very paranoid about the potential overflow from our festival,” Lang concedes. “There were a lot of people coming into town to try to get to Dylan, so it was difficult.” One crusty old-timer, Peggy Egan, demanded at a town meeting that all undesirables arrested for loitering be “deloused and have their heads shaved to clean them up.” Arrests of hippies for trespassing in Woodstock were soon averaging fifteen per day. When they couldn’t pay a $15 fine, they were often packed off to Ulster County Jail for three days.

Yet just as Greenwich Village bohemians had brought much-needed business to Woodstock in the twenties, so now there were well-heeled hippies whose custom was welcomed by the proprietors of its new head shops. (One of those proprietors, Philadelphia importer Leslie Tobin, paid $54,000 for real estate near the village green, converting it into four shops selling hippie clothes and paraphernalia.) “Now they call them hippies,” said plumber Adolf Heckeroth, who’d helped to build the Maverick. “Then they called us anarchists.”

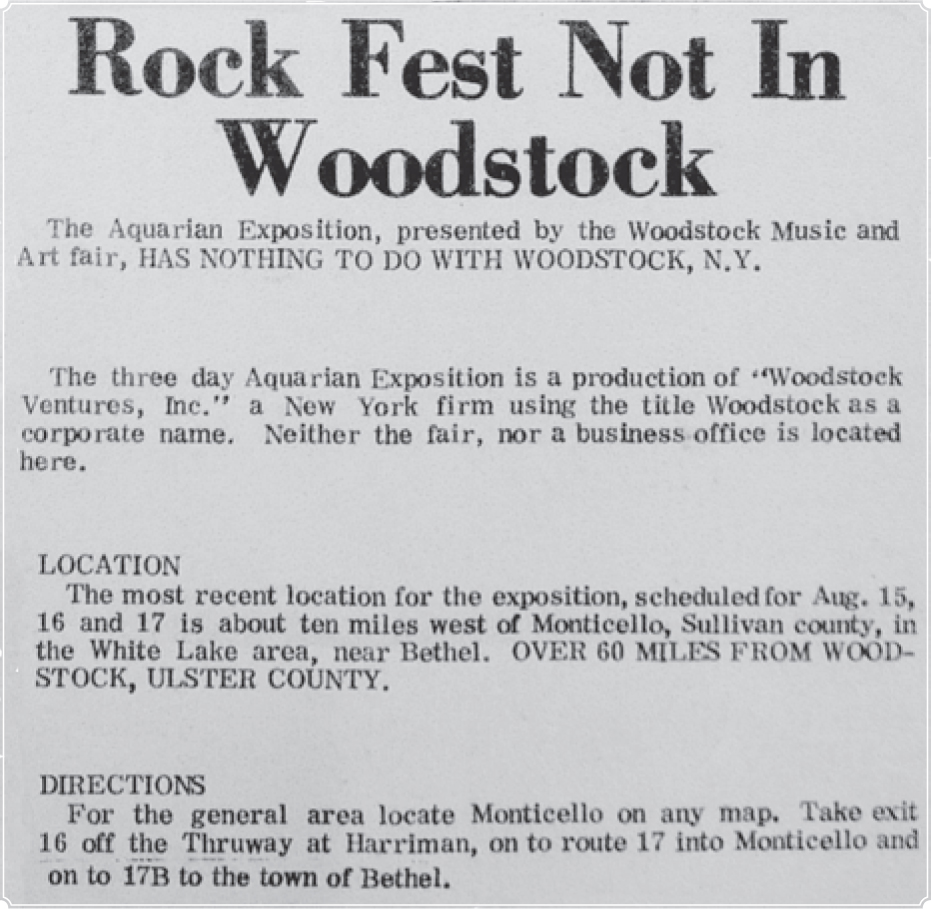

Some natives were more tolerant than others. Where Peggy Egan wanted Woodstock declared a disaster area, Town Justice Edgar Leaycraft told the New York Times that it was “no wonder” young people were being picked up for loitering when the town had failed to provide them with any recreational facilities.** Leaycraft was heavily criticized by old-timers for his “lace-panty justice” and the minimum fines he set for trespassers. Bob Dylan would almost certainly have sided with the apoplectic relics, whose fears were not allayed by a notice in the Woodstock Week that the upcoming “Rock Fest” had “Nothing to Do with Woodstock N.Y.” In the Kingston Daily Freeman, reporter Tobie Geertsema portrayed Woodstock as a small-town Sunset Strip with weekend parades of “teeny boppers and overaged juveniles, girls with straight-pressed blond hair and granny glasses, bearded youths in military coats and surfers’ crosses, leather-garbed motorcyclists sputtering by on their choppers, high school dropouts in giant gilt earrings, stay-ins in General Custer hats, hundreds of elephant-cuffed legs flaunting rebellion.”

Woodstock Week, August 14, 1969

Geertsema additionally listed examples of the impact of the hippie tide on Old Old Woodstock: the shoemaker forced out to make way for a “trinket shop,” the Woodstock Bakery that was now a “mod clothing” store called Saturn. For Cindy Cashdollar, growing up in Woodstock was both exciting and disorienting. “It was like, ‘Where did the little Italian shoemaker go? Where’s the soda fountain?’” she says. “What I knew disappeared and was replaced by this exciting world of colors and characters and smells. I’d never smelled incense before. It was like the circus came to town and never left.” Barbara O’Brien says she understood “the anti-hippie thing” because she came from a long line of Irish cops. “But I saw the clashes on the village green and thought, ‘Why are they doing that?’” she says. “My brain wanted to be where the hippies were.”

In a New York Times piece entitled “Woodstock’s a Stage, but Many Don’t Care for the Show,” Bill Kovach reported on the town’s closure of Big Deep, the swimming hole in which art students had bathed in the twenties. “They shut off the swimming hole from 1969 to 1987 after some nude hippie gave a deputy the finger,” says Ed Sanders. “Woodstock viewed headbands and fringed leather jackets as satanic. They weren’t happy when the hippies feminized masculinity with necklaces and long hair and kaftans.” Richard Heppner points out that Woodstock didn’t become Democrat until the eighties. “I don’t think we had a Democrat on the town board until 1980,” he says. “And that’s because it’s an isolated town. The artists had tried to stir things up, but they were outnumbered. And now even some of the artists balked at the hippies.”

Bill Kovach’s Times piece mentioned the upcoming “Woodstock Festival,” which was expected to draw one hundred thousand to Wallkill’s Mills Industrial Park the following month. Michael Lang was secretly appalled by the soulless suburban location that he and his Woodstock Ventures partners had been forced to settle for, but time was running out. Recruiting the best team available—including Chip Monck, the lighting director who’d once worked for Albert Grossman—Lang set things in motion. By early June it was clear they could not even depend on Wallkill, where locals had mobilized to halt the festival. Meanwhile Woodstockers were still concerned that lawless hordes would descend on their town on the assumption that “Woodstock” was in, well, Woodstock. Republican assemblyman Clark Bell accused Lang and his partners of “romanticizing” the town and deliberately making it known that “Bobby Dylan” lived there. Come July 15, a month away from the festival, Woodstock Ventures no longer had a site for their “Aquarian Exposition.”

Michael Lang claims he was relieved by Wallkill’s rejection. A kind of divine intervention—a phone call from a motel manager who’d been raised in the same Brooklyn neighborhood as him—took Lang to a remote and run-down part of Sullivan County, an hour west of Wallkill. The manager’s property was laughable, but through him came Lang’s first view of “the field of my dreams . . . this perfect green bowl” on a two-thousand-acre property near Bethel. “Michael is desperately trying to find a site,” says Stan Beinstein. “With dumb luck he rides up to this Jewish farmer and says, ‘Have I got a deal for you.’” Max Yasgur, forty-nine, was no hippie, but he was no hillbilly either. He thought Lang and his partners had been treated unjustly in Wallkill. He also calculated he could make decent money out of them, whatever the risks to his land and the ire of his Bethel neighbors. “[Michael] has a way of ingratiating himself,” said Yasgur’s widow, Miriam, not the first person to fall for Lang’s combination of cherub and devil. “I think he’s a born con man. Even though you know you’re being had, you can’t help but like him.”

Through a miracle, Woodstock Ventures had pulled it off. The festival was going to happen, and in the Edenic location Lang had always envisaged. Among those who began to believe was the man who’d played such a big part in establishing “Woodstock” as a countercultural state of mind. “He was a little skeptical about the festival,” Lang recalls of Albert Grossman’s initial response. “But when we moved to Bethel, he came down with Rick Danko to see what was going on. We were standing at the top of the hill, and I was describing what was going on. I said, ‘Down there is the Hog Farm.’” Mention of the New Mexico commune set any remaining doubts to rest: Grossman had known the farm’s founder Hugh “Wavy Gravy” Romney in the days when Romney did stand-up comedy in Greenwich Village.** “I’d gotten Bill Graham on board at that point,” Lang says, “so it was just nice to have Albert on our side too.” With Grossman’s tacit endorsement came the bookings of the Band and Janis Joplin for $15,000 apiece, both crucial additions to the three-day lineup.

Lang felt more trepidation when it came to Woodstock’s biggest star. “I didn’t book Dylan,” he states. “But I didn’t book him for a bunch of reasons. I knew he didn’t like the idea of being the prophet of the hippies, that that was onerous for him. It was known around here, and I knew it from the guys in the Band and other mutual friends. But of course I wanted him to be a part of it.” With artist Bob Dacey, who’d filmed the Miami Pop Festival before moving to Woodstock, Lang went to see Dylan on Ohayo Mountain Road. As Sara made lunch, Lang gave his pitch to the reluctant prophet. He even asked Elliott Landy to help him persuade Dylan to play the festival, or at least show up there. “Bob said, ‘You’d have to bring guns,’” Landy says. “He didn’t want to do it. He said he sensed danger.” Yet Dylan told Al Aronowitz, who lunched with him on August 11, that he’d “been invited, so I know it’ll be okay to show up.” Perhaps Dylan believed he was bigger than the festival; arguably he was. He told Aronowitz that he’d met Lang “but I can’t remember anything about him.”

Later, Lang found himself wondering what would have happened if he’d offered Dylan more money to play. He wondered still harder when he learned that Dylan had agreed—for a whopping $50,000—to headline an English Woodstock on the Isle of Wight, just two weeks after the Bethel festival. “They offered so much dough for Bob to play that nobody could turn it down,” says Jonathan Taplin. Though Bert Block negotiated the deal, Grossman earned almost $16,000 from it, his last big Dylan commission before their contract expired. The hour-long set, with the Band backing him, was Dylan’s supreme kiss-off to the hippie faithful—a low-key country-rock affair performed by six men in suits with short hair.

THOUGH DYLAN NEVER made it to Bethel—notwithstanding rumors that he’d attended in disguise**—Joplin and the Band did. Albert Grossman, however, refused to allow either of them to appear in Wadleigh’s film. “He had a kind of Dr. No thing about him,” Jonathan Taplin says. “He really liked to say no a lot more than he liked to say yes.”

Joplin’s set was only the second with her new Kozmic Blues Band, which was heavy on blue-eyed soul. The Band seemed thrown by the apocalyptic scale of the gathering and struggled to put their restrained mountain sound across to an audience that had had its collective mind blown by the Who and Sly & the Family Stone. “You sit on the big stage watered by the blue spotlights while The Band plays ‘I Shall Be Released,’” Al Aronowitz wrote, “and you look out into the eyes of the monster.” Sandwiched between sets by blues-rock blasters Ten Years After and Johnny Winter, “Tears of Rage” and “I Shall Be Released” underscored the point that Music from Big Pink had been made in reaction to the subculture of rock festivals. “I looked out there and it seemed as if the kids were looking at us kind of funny,” Robbie Robertson recalled. “We were playing the same way we played in our living room. We were like orphans in the storm.”

Equally unnerved by the sea of people in Yasgur’s green bowl was Tim Hardin, who refused to open the festival on Friday, August 15. Michael Lang knew Hardin was on methadone and chose not to force the issue. When the singer finally stumbled onstage at twilight, he threw his musicians a major curveball by instructing them to perform a poem his wife had written about heroin but that had never been set to music. “He said, ‘“Snow White Lady” in F,’” remembered guitarist Gilles Malkine, “and he put this crumpled piece of paper on the keyboard and started playing, and so we just went along with him, but it was a disaster. . . . Okay, you might do that in a café somewhere, but Jesus Christ, the whole world was looking at us!” More felicitous was the five-song acoustic set by John Sebastian, whose tie-dyed jeans and jacket became iconic symbols for the festival. The former Lovin’ Spoonful star caught the vibe of togetherness that was the real story of Woodstock: as many subsequently reported, no one had known there were this many hippies in the entire country.

From Traver Hollow Road, meanwhile, came Jimi Hendrix and his entourage, driven to the site in a stolen pickup truck by roadie Gerry Stickells after it proved impossible to arrange transportation by helicopter. Mike Jeffery quickly became embroiled in a heated discussion with Michael Lang about the timing of Hendrix’s set, Lang warning that things were running chronically late and asking if Hendrix would consider playing earlier. Rigidly blinkered—or perhaps just nervous about how ragged the band would sound—Jeffery refused.

By the time Gypsy, Sun and Rainbows made it to the stage, it was eight thirty the next morning. “I see we meet again,” Hendrix announced after the band had been introduced as the Jimi Hendrix Experience. “Dig, we’d like to get something straight. We got tired of the Experience, and every once in a while we was blowing our minds too much, so we decided to change the whole thing around and call it Gypsy, Sun and Rainbows for short. It’s nothing but a Band of Gypsys.” Most of the “half a million” had left, leaving around forty thousand exhausted stragglers who were treated to a sprawling set of loose blues-funk jams, retooled Experience classics, and frequent delays for the retuning of instruments. At one point Hendrix announced a new song, “Valley of Neptune,” only to realize that he couldn’t remember its lyrics. “We only had about two rehearsals,” he apologized, “. . . but, I mean, it’s a first ray of the new rising sun anyway, so we might as well start from the earth, which is rhythm, right?”

If the supposedly unplanned “Star-Spangled Banner”—by turns blissed-out and mind-shredding—has long been overdetermined as a disturbing coda to a seismic decade, it was still a dramatic reinterpretation of America’s national anthem. After closing with “Hey Joe,” however, Hendrix walked offstage knowing the set had been an unholy mess. “We left by helicopter,” said Leslie Aday, who accompanied him to the old borsht-belt hotel Grossinger’s. “[He was] tired, cold, hungry . . . and unhappy with his performance.”

After a long night of sleep and dope, Hendrix returned to Traver Hollow and asked Claire Moriece to keep the hangers-on at bay. Larry Lee, all too aware of the hostility emanating from Mike Jeffery, made his excuses and left. As Gypsy, Sun and Rainbows slowly unraveled over the ensuing weeks, Hendrix settled for more fluid jams with Philip Wilson and fellow Butterfield Band member Rod Hicks, both loosely affiliated with Juma Sultan’s Aboriginal Music Society. Another local musician was a jazz keyboardist who’d spent time in Woodstock since the mid-sixties. “At that time there was this tremendous division between jazz musicians and rock musicians,” says Mike Ephron, who first came to the house in mid-September. “But I loved Jimi. I brought my electric clavinet, which fascinated him because there weren’t too many electric keyboards around. It had a very funky groove, so we started playing, just the three of us, at about four in the afternoon. And we didn’t take a break till midnight.”

Ephron was part of a fertile avant-garde jazz scene in Manhattan, his loft on Broadway and Union Square a frequent hub for musicians like Pharoah Sanders, Marion Brown, and Sam Rivers. In 1966 he’d rented a house on Woodstock’s Mead Mountain Road, to which those same musicians were often invited. Three years later, living in Glenford with Garth Hudson as his neighbor, he received a call from Juma Sultan. “Juma had come by my loft jams in the city,” Ephron says. “He contacted me to say Jimi had been trying to break away from the mold of the guitar player and all that theatrical stuff.”

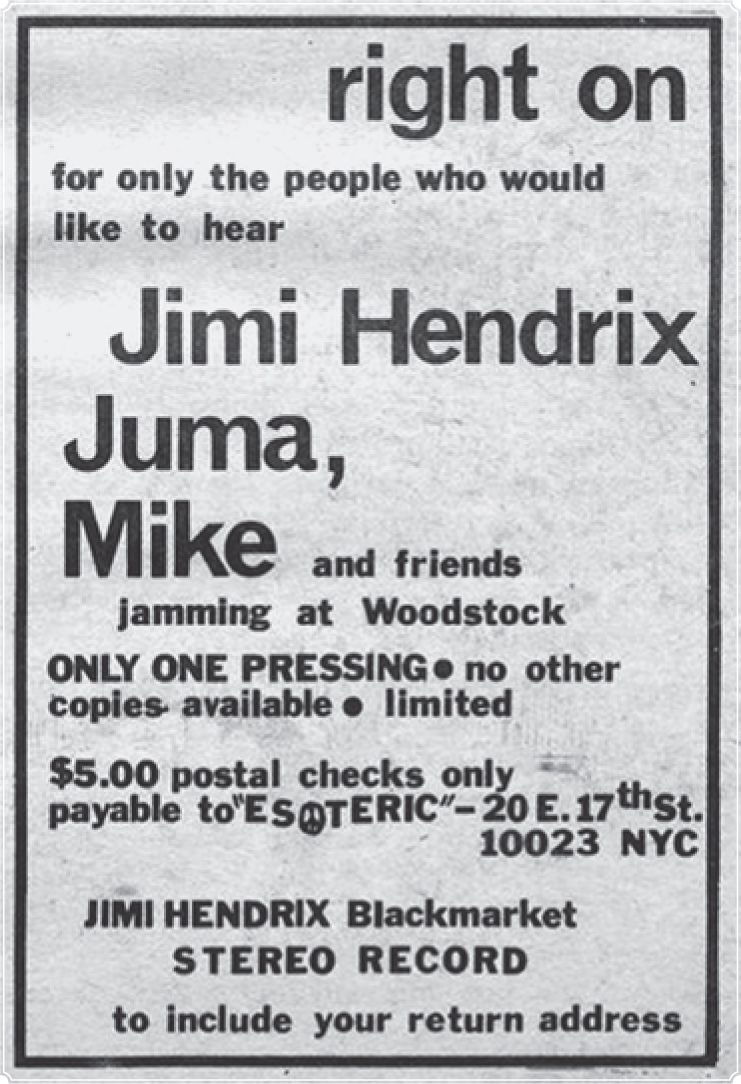

The notorious Mike Ephron bootleg, later released as Jimi Hendrix at His Best

Ephron found Hendrix in good spirits. “It was just all about the music,” he says. “He was doing stuff with feedback that I’ve never heard before or since. He was totally experimenting, going all the way out to lunch.” Among the experiments were “amazing jams” with Sam Rivers and folk-rock duo Bunky and Jake. “Hendrix actually invited Sam to join his band,” says trumpeter Steve Bernstein. “Someone once said to Sam, ‘Wow, your life would have been a lot different if you’d stayed with Charles Mingus.’ He said, ‘Not really. What would have made a big difference is if I’d joined Jimi Hendrix.’”

One of Ephron’s New York girlfriends, Betty Mitchell, told him she’d had a premonition that Hendrix was going to die. “She thought the pressure from his management would drive him over the edge,” Ephron says. “In fact, she proposed that we kidnap him and take him to my place in Woodstock—just to get him away from Jeffrey.” To Ephron, Hendrix was “a shy person, very sweet, who’d sit and write poetry and play his guitar,” whereas Jeffery was “like something out of Performance,” boasting that he’d “‘got Jimi signed up till 1999, mate, he ain’t goin’ nowhere!’”

Ten days after the festival, Jeffery and Jerry Morrison turned up at Traver Hollow in a limousine. They had company—in Sultan’s words “some low-level mafiosi who lived in Willow.” While chauffeur Conrad Loreto engaged in intimidating target practice with a revolver outside the house, Jeffery and his new acquaintances talked to Hendrix and the others about life after Woodstock. Taking Sultan and Velez aside, they offered them contracts with a company fittingly named Piranha Productions, the terms of which promised no advance money and made it clear that they could never play with Hendrix again.** Jeffery was also insistent that Hendrix honor an upcoming commitment at Salvation, a mafia-owned New York club on Sheridan Square.

Neither Sultan nor Velez was easily intimidated—not by smalltime hoods, not by a chauffeur with a revolver. “We had a lot of connections to the Young Lords and the Black Panthers,” Velez said. “It was like, ‘We’re all about peace and love, but if you want to create a dark environment around the guy, you’re messing with the wrong people.’” Hendrix, however, was genuinely scared by what these people could do to him. “He was a soft, lovable guy, [there was] nothing violent about him at all,” said Velez. As a result, Hendrix did what he was told. On September 10 he played Salvation with Sultan, Velez, Billy Cox, and Mitch Mitchell. “It was basically a disaster,” Velez said. “The sound sucked. It was a small place, not really set up for a band like Jimi’s. Jimi walked off after a while saying, ‘This is bullshit.’”

What happened after that, only Hendrix really ever knew. He told his old friend and biographer Curtis Knight that, as he walked away from Salvation with its co-owner Bobby Woods—who also happened to be his coke dealer—he was forcibly abducted by four men who blindfolded him and drove him to an apartment in Brooklyn.†† Some maintain the kidnapping was orchestrated by Mike Jeffery himself, who then came heroically to his client’s rescue to prove he was on his side. Juma Sultan has said that when Hendrix returned to Traver Hollow, he laughed about how “Mike and his crew came in like gangbusters and rescued him.”

If things had settled down by the time Sheila Weller visited Traver Hollow in mid-September, whatever idyllic moments Hendrix had experienced upstate were coming to an abrupt close. Soon he stripped Gypsy, Sun and Rainbows down to the three-piece Band of Gypsys, with Billy Cox and ex–Electric Flag drummer Buddy Miles playing behind him. After the first Catskills snowfall that autumn, Hendrix left the “Sky Church” and never returned. When owner Glen Markett came to inspect the house, it looked like an abandoned commune: one bedroom had been painted black, another boasted a mural of a flying saucer descending over a mountain; rugs had numerous burn marks, and wax from candles had spilled everywhere.

Back in Manhattan in the summer of 1970, Hendrix had a brief encounter with the author of “All Along the Watchtower,” who happened to be cycling past the guitarist’s limousine. “It was an eerie scene,” Dylan remembered. “He was slouched down in the back. . . . It was strange, both of us were a little lost for words. He’d gone through like a fireball without knowing it. I’d done the same thing, like being shot out of a cannon.”

Relations with Mike Jeffery did not improve. When Hendrix played England’s Isle of Wight festival that summer, he told Richie Havens his managers were “killing” him, that he couldn’t eat or sleep. Havens recommended he speak with his attorney Johanan Vigoda, who had just bought his own Woodstock property off Ohayo Mountain Road.** “I told Jimi I would be glad to introduce him and that I would be in London for four days after the festival,” Havens wrote. “I told him to come by and see me when he left the Isle of Wight. He never showed up. The next thing I heard about him was some three weeks later. He’d been found dead.”

After Hendrix’s death on September 18, 1970, Mike Jeffery continued to spend time in Woodstock. “He’d become an embarrassment to many in town,” wrote Paul Smart, “albeit one with a constant supply of drugs.” A 1972 report on Woodstock in Harper’s magazine referred to Jeffery’s “financial problems” and said the local sheriff was “threatening to put his extravagant house up for sale to satisfy a bad debt.”

After Jeffery died in a midair plane collision over Nantes on March 3, 1973, the high fences around 1 Wiley Lane stayed in place. They were, Smart wrote, “an odd memorial to the wild rock ’n’ roll lifestyle hidden behind its quiet country façade.”

![]()

* For four years, Edgar “Pete” Leaycraft lived next door to me on Zena Road, and his son Matt was my landlord. You couldn’t have asked for a nicer neighbor or a fairer landlord.

* According to Bob Spitz, it was on Romney’s typewriter that Bob Dylan had typed out the lyrics to “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

* When he played the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts on the festival site in June 2007, Dylan muttered that “last time we played here, we had to play at six in the morning, and it was a-rainin’ and the field was full of mud.”

* There remains much confusion as to what actually happened at Traver Hollow that day. Electric Lady Studios engineer Jim Marron claimed “four or five mobsters came up to Shokan in a car, walked in with their guns out,” and told Hendrix he was under house arrest, prompting Mike Jeffery to call in a favor from a Long Island mafioso. But Jerry Morrison told Jerry Hopkins it was he who had come to the guitarist’s rescue.

† Almost five months later, Woods was found dead in Queens with five bullets in his head. It seems likely he paid the price for standing up to the mob.

* Vigoda was a maverick New York lawyer who, among other things, renegotiated Stevie Wonder’s contract with Motown’s Berry Gordy. (It’s his voice you hear as the judge sentencing the hapless protagonist of Innervisions’ “Living for the City.”) He also extricated Hendrix from an early contract with Sue Records and represented Michael Lang and his partner Artie Kornfeld in the dissolution of Woodstock Ventures. “Even though he was an attorney, he kind of had this artistic soul where he wanted to do good things for artists,” says Paula Batson, who worked for him. “He would do very funny things in his negotiations, like eating the contract as he was talking. And the other attorneys would just be like, ‘Whatever you want, just stop eating the contract!’” Vigoda died in Nevada in 2011.