FOR MANY, WOODSTOCK ruined Woodstock. Though people had not descended on Tinker Street in the expected droves during the festival itself, they certainly showed up after the event had made “Woodstock” a global buzzword. “You see them arrive at the village green,” said Lynda Sparrow, manager of the Happiglop leather goods store. “They come in here and say, ‘You mean, this is it? This is all there is?’”

As they had been before the festival, Woodstock’s elders were up in arms about the hippie drifters. “We are not opposed to [them],” Town Supervisor Milton Houst said before getting to the nub of the matter. “We want visitors and we don’t want to keep anybody out, but this place is like everywhere else in the world: you need money to stay here.”

“What concerned the town was that the musicians were bringing in people with no means of support,” says Richard Heppner. “The way welfare rules worked here, the town was responsible for paying a good portion of any type of grant that you got. But it was such a mess that Woodstock took a stand and refused to allocate funds to these people.” In 1970 the crisis intervention center FAMILY of Woodstock, run by Gael Varsi, was established at 13 Library Lane to help troubled kids who’d wound up in Woodstock—many of them runaways from abusive backgrounds. For most of the young seekers it was irrelevant that Woodstock hadn’t taken place in Woodstock: the town by now was a sacred place and home not only to Bob Dylan but to the Band, Van Morrison, and many more.

“Woodstock turned into a place where a lot of young kids would come up and seek the ancillary aspects of being at the festival,” says Martha Velez, who lived near Dylan’s old house and even wrote a song, “Byrdcliffe Summer,” about her life there. “Which was that if they were there, they were now part of the scene. And really they weren’t; they were simply part of a commercial aberration for Woodstock.” The upside of this was that the town’s population grew large enough to support a vibrant live music scene; the downside was the commodification of the counterculture itself. “Once Dylan had gone, what was presenting itself mimicked what he had done or been about,” says Bruce Dorfman. “I didn’t feel the community was vital anymore, and it was becoming very commercialized. Suddenly all these little shops opened that sold fancy lollipops. It was turning into some sort of tourist place.”

“There was nothing about the place that changed,” says Daoud Shaw, who drummed in Martha Velez’s band at the Espresso and the Elephant. “It was just what was happening in society at the time. Labels came out of the woodwork and signed anything that walked. If it’s a rock and roll band, sign it, wind it up, and it’ll make money.” Some of the visitors came and never left—or at least those willing to brave the Catskills winter. “With the phenomenon of the Woodstock festival came the kind of accidental settlement of the town as a rock community,” says Cindy Cashdollar. “It was as if everybody thought, ‘Oh what the hell, we’ll just stay here!’”

FOR DYLAN HIMSELF, it had all finally become too much. Even behind the gates of the Ohayo Mountain Road house he felt vulnerable and persecuted. In 1985 he spoke of “people living in trees outside my house, trying to batter down my door, cars following me up dark mountain roads.” When Charles Manson and members of his “Family” were arrested in connection with the savage murders of Sharon Tate and her friends (and of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca), Dylan was as freaked out as any of the musicians who’d crossed Manson’s path. Who knew what barefoot psychos might show up on the Dylans’ doorstep. Though he continued to patronize such local establishments as Norma Cross’s Squash Blossom Café—where he often breakfasted—he was desperate to destroy the messiah image that had made him such a magnet.** On one occasion he emptied a bottle of whiskey over his head and strolled into a department store, hoping the story would spread and deter the countless disciples he’d never solicited.

“Bob was more of a sitting duck out there,” says Maria Muldaur, who often visited the Dylans. “People were walking onto his property. At first he was kind of nice about it, but it got old really quick.” Trying to hold onto his sanity, Dylan socialized with old folkie friends like the Muldaurs and the Traums. One winter’s night he appeared at Maria’s door in a huge fur hat. “I said, ‘What are you doing here, Bob?’” she recalls. “He said, ‘Jim Rooney told me Bob and Betsy [Siggins] were here. Can I come in?’ So he would just kind of appear when there was something interesting going on.”††

Soon, not even the presence of old friends who treated him like a normal person compensated for the hassles he regularly endured in Woodstock. “There was always the unseen presence of Dylan,” says Keith Reid. “Everyone knew he was there, but no one ever saw him. It was always like, ‘He was here—you just missed him.’” Dylan seemed to retreat ever deeper into himself. “There were some very good artists living on Ohayo Mountain Road, but Bob had very little contact with any of them,” says Bruce Dorfman. “It was surprising to me, but I think at that point there were disruptions beginning to happen in his life. The amount of attention that was given to him magnified things enormously—for everybody, but especially for him.”

When Eric Andersen came to stay on Ohayo Mountain Road, he found a different Dylan from his previous visit. “He was definitely into his kids, but I didn’t get the feeling he was relaxed,” Andersen said. “He was trying to be nice, but you could tell things were going on. . . . His mind [was] just flying all over the place.” It was as if the three-and-a-half-year experiment in trying to be a regular guy was finally faltering. In Chronicles he was unequivocal: “Woodstock had turned into a nightmare, a place of chaos. Now it was time to scramble out of there in search of some new silver lining.” He was more cryptic in a Playboy interview in 1978: “It became stale and disillusioning. It got too crowded, with the wrong people throwing orders. And the old people were afraid to come out on the street. The rainbow faded.” He even contemplated a move to Nashville, viewing properties in the city with Bob Johnston.

For Dylan, Woodstock was transformed from a sanctuary—both domestic and creative—into a kind of prison. The festival was “the sum total of all [the] bullshit,” he wrote later, and “I got very resentful about the whole thing.” When Larry Campbell played with him between 1997 and 2004, the two men periodically talked about the town they’d both lived in. “Bob laughed when I told him Garth Hudson still had his old station wagon, but there were never any conversations where he reminisced fondly about the place,” Campbell says. “With Bob it always seemed like, ‘Well, I did that, and now I don’t do that anymore.’ I do remember asking what he was doing up here, and he put it very simply. He said, ‘I was raising a family. That’s all I was interested in at the time.’”

Dylan continued to use the Ohayo Mountain Road house as a second home through the early seventies. Even then, with its owner mostly absent, the house attracted unwelcome visitors. George Quinn, who house-sat the property as a teenager, remembered “these really strange characters showing up at all hours—people who were not too mentally stable.” By the summer of 1970, Dylan was wearying even of occasional visits to Woodstock. One afternoon he stopped by the Sled Hill Café and asked bartender Jeremy Wilber to fetch Oklahoman singer-songwriter Roger Tillison’s acoustic guitar from the back room. No sooner had he struck a chord on it than two young women walked in and shrieked with disbelief. “Bob put the guitar down and left,” says Wilber. “And that was the last time I ever saw him here.”

One of the reasons the Dylans still spent time upstate was that their new life on MacDougal Street—where they’d moved shortly after the birth of son Jakob in December 1969—wasn’t quite working out the way Dylan had planned. With the notorious A. J. Weberman rifling through his garbage, and other mad radicals of the era accusing him of selling out, Dylan was soon regretting the nostalgic impulse that had taken him back to Greenwich Village. He later complained that “the Woodstock Nation had overtaken MacDougal Street,” as though Woodstock itself had somehow corrupted the old Village he now longed for. “Albert Grossman was obviously very tough,” says Ed Sanders. “When Dylan left him, he was left without a Pretorian guard. People like Weberman and the Yippies could hound him.” Interestingly, Dylan refrained from mentioning Grossman’s name, even with people who’d known them both. “We never had any conversation about Albert at all, though I knew they’d fallen out,” says Michael Friedman. “Albert never talked about it either, probably because he knew that the word was out there that he had overreached.”

Dylan was also being serially unfaithful. “He was fooling around with other people, and that was pretty well-known,” says one former employee. “When he came back from the Isle of Wight, he was very much the family man, but I distinctly remember being in Naomi Saltzman’s apartment and there was a girl measuring him for a costume. They were in there with the door closed, and I knew they were fooling around.” Bruce Dorfman says he never saw Sara Dylan in the city. “It was pretty much Bob and his pinball machine in the living room,” the artist remembers. “I can’t imagine how Sara even stayed in the place.”

Dylan tried to throw people off the scent again with the mischievously titled Self Portrait (1970), whose mixture of cornball-country and MOR-folk covers infuriated diehard disciples even more than Nashville Skyline had done. “Being at the Self Portrait sessions, I was like, ‘What the hell is going on here?’” says Al Kooper, who lived nearby and saw a lot of Dylan in this period. “I said to myself, ‘Why is he doing other people’s songs?’”** Decades later, much of Self Portrait and its better-received follow-up, New Morning, was rehabilitated and reclaimed when the box set Another Self Portrait offered stripped-down takes of tracks originally marred by cloying overdubs.

Ironically, three of the set’s highlights celebrated the country life Dylan had all but given up. Written for a play by Archibald MacLeish, “New Morning” itself might have hailed from the first flush of Dylan’s love affair with Woodstock, while “Time Passes Slowly”—first recorded in New York with a visiting George Harrison—similarly evoked the pastoral charms of Dylan’s Catskills hideaway.** Yet the ambiguity of “Time Passes Slowly” was hard to miss: as seductively peaceful as the picture looked (“We sit beside bridges and walk beside fountains”), the apathy (“Ain’t no reason to go anywhere”) and the mild desperation (“We stare straight ahead and try so hard to do right”) were equally clear. One could have said the same of the gorgeous “Sign on the Window,” a song of emotional thawing-out and desire for family that sounded like a man trying a little too hard to convince himself that “that must be what it’s all about.”††

SIMILARLY STRUGGLING TO convince himself that “that must be what it’s all about” in Woodstock was the Ulsterman who lived at the top of Dylan’s road. Van Morrison was trying to contain his own restlessness as he played Happy Families with Janet Planet and his stepson. Like Dylan, too, Morrison was instinctively repelled by the very idea of the Woodstock Festival. While he happily admits that Michael Lang never invited him to play at Bethel, he says that in retrospect he was “lucky” not to have been part of its “mythology and typecasting.”

“Van just sensed that he didn’t want to have anything to do with it,” says John Platania. “He would speak in disparaging terms about it before it even happened.” After the festival was over, Morrison claimed he’d moved to Woodstock to escape the scene, “and then Woodstock started being the scene. . . . Everybody and his uncle started showing up at the bus station, and that was the complete opposite of what it was supposed to be.”

Despite the crabbiness he shared with Dylan, Morrison remained in Woodstock for another eighteen months. He was sufficiently taken with the town’s spirit to piece together the quasi-communal Street Choir, expanding the Moondance lineup to include new players and singers. Assisting him in this was an ambitious new manager, Mary Martin, who’d graduated from Albert Grossman’s office after hooking Dylan up with the Hawks.

“Mary commanded respect and really got this whole thing moving,” says Daoud Shaw, who’d replaced Gary Mallaber in Morrison’s band. “I could see from the get-go that she was on Van’s case to get him happening. She was constantly at gigs, constantly working.” Janet Planet later claimed that Martin had urged her not to let Morrison “get too happy,” lest his music suffer in the process. Janet was appalled, since her all-consuming obsession in life was to make her husband feel better about himself. “Hanging out with Van was like hanging out with someone from Mars,” says Shaw. “But then again it could be really fun, like getting a call at three a.m. saying, ‘I heard there’s a barber at this hotel who used to do Sinatra’s hair. Let’s get haircuts!’”

Coming together in the spring of 1970, the Band and Street Choir replaced a frustrated Jef Labes with keyboard player Alan Hand, and saxophonist Collin Tilton with Paul Butterfield’s trumpeter Keith Johnson. The Choir itself consisted of Janet; Jack Schroer’s wife, Ellen; and Keith Johnson’s pregnant girlfriend, Martha Velez; along with Daoud Shaw, Larry Goldsmith, and Andrew Robinson. “Initially it was just ‘Come on up,’” says Shaw, whom Morrison heard jamming with some of Butterfield’s musicians at the Espresso. “And I just kept going and playing. I would close my eyes and listen to him singing, and it was different every time.”

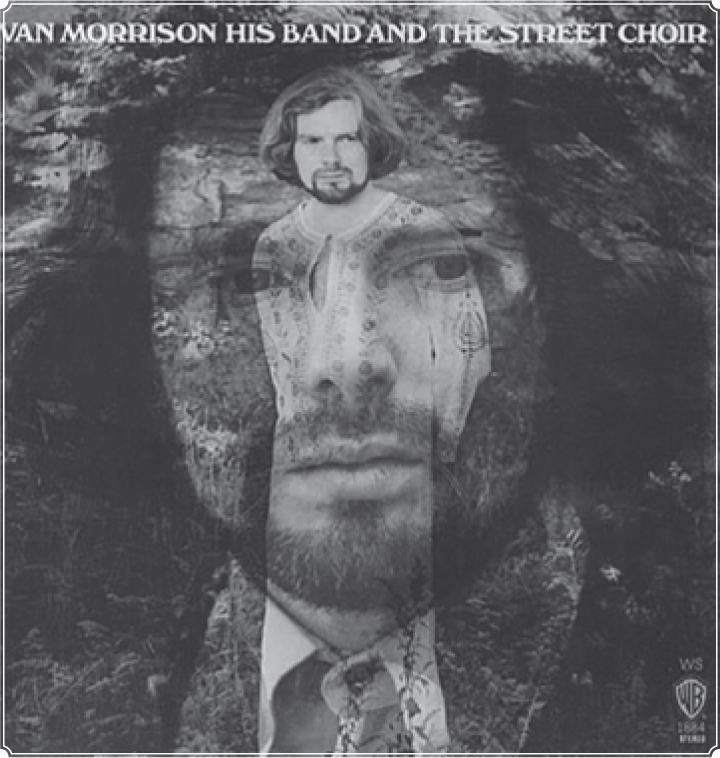

Early demos for 1970’s His Band and the Street Choir were done in a homemade studio that Shaw had built in nearby Hurley. “I had a two-car garage,” he says, “and from that we built a studio right from the ground up. We called it Stone Sound.” The feel of the demos was akin to the gypsy soul of Moondance but looser, more laid-back. On the surface the vibe was good, and Janet seemed to think she was “winning the battle” between the light and the darkness in her husband’s brooding soul. In her liner notes for the album she wrote that she had “seen [him] open those parts of his secret self—his essential core of aloneness I had always feared could never be broken into—and say, ‘Yes, come in here. Know me.’”

“Van really bought into the whole community aspect of trying to have a big family feel,” says Martha Velez. “To be up in Woodstock and to have people sing choruses in that way was a very big step for him.” In a lengthy Rolling Stone interview that summer, Morrison told Happy Traum that recording his third Warners album was “very human . . . there was no uptightness about it.” Yet behind the geniality, he worried about losing control. “It was probably something he got himself into by saying ‘Okay,’” says Shaw, who wound up with a credit as Van’s assistant producer. “The vibe was street-corner, a bunch of guys singing together. It was like he couldn’t say no. Domestic relations took over from casting the film.”

“It was too hippie for me,” Morrison confirms today. “A lot of it was well-meaning, but the people didn’t get that I had been in the music business for a long time. So it led to a lot of problems, because they couldn’t really take any direction.” Having got his early grounding on the ballroom circuit in his native Northern Ireland, Morrison abhorred the sloppy jamming of late sixties rock. “I was coming out of the tradition of blues and R&B,” he says. “I didn’t really play any rock gigs till I got over to America with Them, so it took some time to get used to what that was.” He became so impatient with the Choir’s deficiencies that for the soul ballad “If I Ever Needed Someone” he reinstated the New York backing trio that had sung behind him on Moondance’s “Crazy Love” and “Brand New Day.”

In true seventies rock parlance, Morrison even claimed that everything was ruined when “the old ladies got involved.” One of those ladies, Velez, found Morrison “very enigmatic and very difficult to approach,” often just because his thick Ulster accent was near-impenetrable. “But I really respected his need to be a creative person,” she adds. “He always said that the music channeled through him and he just had to catch it. When it’s that much of a visceral experience, it really requires a lot of trust in the viscera.”** The problem with His Band and the Street Choir was that it wasn’t visceral enough. Possibly because Morrison was producing his own music for the first time, the sound at New York’s A&R studios was flat and lackluster. Even “Domino,” which gave him a top 10 hit at the end of the year, missed the feel and dynamics of Moondance: both it and another early Woodstock number, the funky “I’ve Been Working,” suffer by comparison with their thrilling treatments on Morrison’s live It’s Too Late to Stop Now (1974). But the material in any case was weak next to Moondance. “Crazy Face” was no “Crazy Love,” and the acoustic “I’ll Be Your Lover, Too” sounded like an Astral Weeks reject. Up-tempo R&B tracks “Blue Money” and “Sweet Jannie” never really got going, while “Gypsy Queen” unsuccessfully mated the gossamer soul of “Crazy Love” to a pastiche of Curtis Mayfield’s Impressions. Only the closing “Street Choir” revived the Band-steeped feel of the previous album.

Morrison felt the deficiencies keenly and later complained that he’d been pushed into making the album too quickly. He also detested the cover, which displayed him in a comical kaftan he’d bought in one of Tinker Street’s head shops. He wasn’t even sure about the happy-feely pictures that David Gahr took of him with his band members in the woods behind Spencer Road. Missing from them was John Platania, who’d temporarily fallen out with his employer. “It was almost like a fight I’d get into with my brother,” Platania says. “He put the road manager in the picture instead of me.” In the pictures, however, was Morrison’s baby daughter, Shana, who entered the world on a chilly night in April. Janet’s long labor had been so traumatic that Morrison called the Gershen brothers from Kingston Hospital and asked them to help him make it through the night.

The Gershens’ friendship with the Morrisons continued for the remainder of 1970; Morrison even posed with the Montgomeries for one of Gahr’s outdoor shots.** “He would just call up and say, ‘What are you doing?’” Jon Gershen remembers. “We’d get together and play Hank Williams records. We weren’t looking for anything from him.” The Gershens took Morrison to see their attorney, Alan Bomser, in New York, hoping he might be able to help him retrieve some of the money the singer was owed. “Van offered the example of ‘Gloria’ and said he’d never received a penny for it,” says Jon Gershen. “Alan said, ‘You mean the “Gloria”?’ Within fifteen minutes he says, ‘I’m seeing at least a quarter of a million dollars that should be in your pocket from that song alone.’ It seemed to me that Van really didn’t have a clue about the music-publishing business.”

The brothers also witnessed the growing friendship between Morrison and Richard Manuel. “They were close pals,” Mary Martin told me in 1991. “For Van, Richard was the real soul of the Band.” Alcohol apart, the two men had specific musical passions in common and talked of collaborating on an album of Ray Charles songs. Manuel also made Morrison howl with laughter. “Canadians had a different sense of humor than Americans, and I understood that more,” Morrison says. “Richard was a very funny guy. His one-liners were killers.” To Morrison’s old sax player Graham Blackburn, the two men were born soulmates—both extraordinary singers, both painfully introverted. “The basis of the friendship was that they could come together on equal terms,” Blackburn says. “From my perspective as an English immigrant, the Band had a problem as Canadians who felt like second-class citizens. But for them it was irrelevant that Van was Irish and Richard Canadian.”

Morrison’s acceptance by the Band, and by Manuel in particular, almost compensated for his failure to befriend Bob Dylan. He did, however, have one long phone conversation with his Ohayo Mountain neighbor. “Bob was talking about a revue, sort of like the Rolling Thunder one he did later,” Morrison says. “He said he was thinking about having different singers come out with him.” Maria Muldaur confirms that Dylan was “all fired up about an idea of traveling across America on a train.” She remembers him saying, “Why don’t you guys and me and the Band and Butterfield and Janis ride across the country?” That summer of 1970, the tour happened exactly as Dylan had envisioned it—but without him, the Muldaurs, or Van Morrison.

Quite how Morrison and Manuel weren’t killed drunk-driving is a Woodstock mystery. “The drinking thing was a fixture of [Van’s] existence at that time,” Jon Gershen said. “He would come over with a fifth of Johnnie Walker Red and plump himself down on the floor. Driving back to his house on those back-country roads, it’s a wonder we didn’t get wrapped around a tree.” When Morrison and Manuel did finally get around to recording together, fittingly it was on a song whose title referred to the difference in alcohol percentage between Johnnie Walker Red and Johnnie Walker Black. “They were totally drunk by the end of the session,” says Jim Rooney, who witnessed it. “Richard drove Van home, but Van had a circular driveway, and after he let Van out of the car he just kept coming round and round the circle. He almost ran Van over.” A song about an inebriated evening the pair had spent together in Los Angeles, “4% Pantomime” was recorded in early 1971 in a new studio built by Albert Grossman.** It was also one of the last things Morrison did before following Janet and their kids back to her native California. Just before Christmas 1970, he announced to the Street Choir that he was forming a new group with guitarist Doug Messenger, whom he’d just flown in from California. “I’ve got a problem,” were Morrison’s first words to Messenger. “I’ve got to stop drinking.” The next morning, Messenger awoke to find Morrison sitting at the foot of the bed and the entire group assembled around them. “Doug and I are starting a band,” Morrison informed them, “and you’re all fucking fired!”

The jury is still out on whether—after two “farewell” shows at the Fillmore East in February 1971—Morrison genuinely wanted to leave. “I think he really loved Woodstock,” says John Platania. “It was Janet who wanted to go back to Marin County.” Significantly Morrison included his paean to “Old Old Woodstock” on 1971’s Tupelo Honey, his first California album, and sang in it of the town’s “cool night breezes” and “shady trees.” (The water “flowing way beneath the bridge” was almost certainly the Sawkill passing under Tannery Brook Road at the bottom of Ohayo Mountain Road.) He also sang of his woman “waiting by the kitchen door,” which may have been one of the factors in the eventual breakdown of their marriage: he was dead-set against Janet pursuing a career as an actor. And yet the self-explanatory “Starting a New Life” was the plainest statement of a fresh beginning. “That was pretty much representative of what was going on,” says Tupelo Honey’s producer Ted Templeman. “Van had moved out of Woodstock, and they were starting again.”

Morrison claims he was welcomed in Marin County with a friendliness he’d never experienced in Woodstock. “California was very different,” he says. “Everybody was very open, whereas Woodstock was very closed.” Of the town he’d left behind on the East Coast, he says that “if you didn’t buy into the hippie vibe, then you were out.” But he also says that “everyone was very reclusive, and there was a lot of paranoia going around.” Perhaps it’s his own paranoia he is talking about: he may have underestimated how difficult it was for his Woodstock peers to understand the man Richard Manuel dubbed “the Belfast Cowboy”—or how intimidatingly grumpy he came across.

Years later, another British singer-songwriter who’d settled in Woodstock was touring Europe as Bob Dylan’s support act. At a Belfast show, none other than Van Morrison showed up backstage. “He said to me, ‘So you live in Woodstock,’” says Graham Parker. “I said, ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘Fuckin’ horrible place. Well, whatever works for you.’”

WHETHER TIM HARDIN felt the same way about his adopted town we can’t know. After the opiated debacle of his Woodstock festival appearance he continued to operate in his usual desultory fashion. “He’d fire me,” says Warren Bernhardt, often Hardin’s sole backing musician, “and then I’d run into him on the street, and he’d say, ‘Hey, I got a bunch of gigs coming up, you wanna do ’em?’ And this went on for, like, six years.” During a show in San Diego, Hardin marched onto the stage and announced he had heartburn. “So here’s Bernhardt,” he added before splitting to catch a plane. “Leaves me on the stage with ten thousand people, just me and a clavinet,” Bernhardt recalls with a chuckle. “Pretty interesting.”

Managed by Jerry Wapner, a hip lawyer who’d swapped Brooklyn for Woodstock back in 1964, Hardin moved from Zena Highwoods Road into a place near Boiceville known as the Onteora Mountain House. “I drove him to the closing of the property,” Wapner recalled in 2013. “We drove back to the place and he got out of the car and there was a huge flagpole right in the center of the circular drive. . . . [He] pulled down the American flag—I don’t think he meant any disrespect—and he pulled out of his pocket a Jolly Roger flag [and] hoisted it high. I must say, that ingratiated him even more to me.” Hardin regularly surfaced in Woodstock, where his eccentricities became the stuff of local legend. “Ten thirty in the morning,” Warren Bernhardt says, “you’d walk out, and there would be Tim in a short bathrobe wide open, nothing else, in cowboy boots and a hat, walking through town. There were a million things like that.” During a loose musicale at Jim Rooney’s house in Lake Hill, Hardin got so drunk that he fell on somebody’s upright bass and broke it. For his sins, Rooney’s wife, Sheila, “dragged him by the ear and threw him out in the snow.”

Against all odds, Columbia kept faith with Hardin, though it warned producer Ed Freeman what to expect of his new charge. Sensibly, Freeman recorded most of the instrumental tracks for Hardin’s next album ahead of the singer’s erratic visits to the studio. “It was a funny combination of thinking Tim walked on water and realizing he was virtually impossible to work with,” he remembers. “I had to piece a lot of stuff together with Scotch tape, but at the same time he was unquestionably brilliant.” Low on original songs, Bird on a Wire nonetheless stood up as one of Hardin’s most focused collections, kicking off with a soulful treatment of the Leonard Cohen title song. The album ended with “Love Hymn,” a maudlin account of Hardin’s courtship of—and abandonment by—Susan Morss, who “drove off with a new friend out west to L.A.”

When Bird on a Wire made little more impact on the charts than its peculiar predecessor had done, Hardin decided it was time to leave not only Woodstock but America. With its registered heroin addicts, England had always looked attractive to him. In 1971 he uprooted to London, recording most of his last Columbia album there with ex-Shadow Tony Meehan producing and a cast of sidemen that included former Humble Pie guitarist Peter Frampton. This time not a single original song made the cut—probably because Hardin hadn’t written any. Painted Head concluded with a long country-soulful working of Jimmy Cox’s immortal blues “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out.”

![]()

* The Squash Blossom—on the Tinker Street site where former Blues Magoo Michael Esposito now runs his bicycle repair shop—was one of Woodstock’s great meeting places. “It was a sort of breakfast-and-lunch place,” says Stan Beinstein. “Norma lived upstairs, and she had lace curtains and antiques around. We’d roll out of bed and go there, and that’s where you saw everybody.”

† Bob Siggins had been a member of the Charles River Valley Boys; Betsy had worked at Cambridge’s Club 47.

* In Chronicles, Dylan wrote that he’d urged Albert Grossman to pair Kooper with Janis Joplin. Grossman replied that it was “the stupidest thing” he’d ever heard. “I should have been a manager,” Dylan hilariously concluded.

* Harrison, who’d spent further time with him on the Isle of Wight, wrote another song—“Behind That Locked Door”—about trying to reach out to Dylan. Along with “Time Passes Slowly,” the two men recorded a number of other tracks at Columbia’s New York studios, including the tongue-in-cheek “Working on a Guru” and a version of the Beatles’ “Yesterday.” On his ambitious triple-album debut All Things Must Pass, Harrison included not only “Behind That Locked Door” and the earlier Dylan cowrite “I’d Have You Anytime” but “If Not For You,” a Tex-Mex-flavored song of amorous devotion that was New Morning’s only single. The following year he used all his powers of unconditional friendship to coax a terrified Dylan back onstage at the Concert for Bangladesh.

† Unconvinced by New Bob, of course, were the likes of Country Joe McDonald, who said he wasn’t “fooled,” and the deranged Weberman, who declared he’d “come to the conclusion that Dylan has turned into a HYPOCRITE AND A LIAR.”

* After the dissolution of the Street Choir, Velez recorded her second album Hypnotized with the core of Morrison’s 1970 band—plus her brother Jerry. “It’s clearly a Woodstock album,” she says. “We woodshedded it at Byrdcliffe and then at a little house in Glenford. The winters there were fabulous for wood-shedding, because there was nowhere to go.”

* The photo session was arranged by Mary Martin, who was attempting to put together a nationwide package tour featuring Morrison, the Montgomeries, and—as headliners—the Byrds. When the latter band dropped out, Martin lost her interest in managing the Montgomeries and eventually stopped managing Morrison.

* At the end of the outtake version of “4% Pantomime” on the Band’s A Musical History box set, one hears the voice of Garth Hudson saying, “That was spectacular.” Equally spectacular was the ecstatic version of Moondance’s “Caravan” that Morrison sang with the Band at the Last Waltz in 1976.