oh lord won’t you buy me a mercedes benz

FOR GEOFF MULDAUR of the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, the “big breakthrough” at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival wasn’t Bob Dylan’s scandalously amplified set on the Sunday night but Friday afternoon’s performance by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. “In the blink of an eye,” Muldaur told Woodstock writer John Milward, “there would be two hundred thousand blues bands in the world based on that model.”

Presaging the American blues-rock wave of the late sixties, just as the Yardbirds and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers were doing in England, the interracial Chicago group tore up Newport’s Blues Workshop, with Butterfield’s and Mike Bloomfield’s searing licks solidly anchored by Howlin’ Wolf’s former rhythm section of drummer Sam Lay and bassist Jerome Arnold. “We were a little too chaotic for them,” says Barry Goldberg, whom Butterfield had invited to join them at Newport. “It was white kids playing the blues, first of all, and they couldn’t accept it. But it was really cool. Paul was a great entertainer, and Michael was never one to turn down: the more people resented it, the louder he got.” Maria Muldaur, who watched open-mouthed with fellow members of the Kweskin band, had never seen anything like it. “I’d heard a lot of early R&B,” she says, “but to see it live with the power and dynamics and energy those guys brought to it was something else. Plus it was the first integrated band I ever saw.”

Crowning the whole event was the almost comical fistfight that erupted after the set, when a livid Albert Grossman confronted song collector Alan Lomax to berate him for the condescending way he’d introduced the band.** “That was the dumbest introduction I have ever heard!” Grossman yelled before launching himself at Lomax and shoving him to the ground. “We didn’t know what had started it,” says Maria Muldaur. “All of a sudden these two big bears are scuffling around in the dirt.” For Barry Goldberg, Grossman’s rage toward Lomax made him an instant hero. “It was sort of obscene to see these two old guys rolling in the dirt,” he says, “but when Albert went to that extreme and cared so passionately for his band, that won me over.”

Grossman had been turned onto Butterfield’s trailblazing group by Paul Rothchild, who’d seen them play in their native city at the start of the year. “It was thrilling, chilling,” Rothchild said in 1990. “[It] changed my entire genetic code.” Butterfield was a fiery Irish American whose electrifying harmonica phrases were the only answers anybody needed to the hoary question “Can white men play the blues?” “I knew Paul was great, but I didn’t know how great,” says Geoff Muldaur. “I was in Cleveland with him once, and Cannonball Adderley turns to me and says, ‘Do you know who the fuck you’re playing with?’ Paul took it to a place where, if you have the courage, you’re risking death when you do it.”

The same might have been said of the super-hip Bloomfield, who was persuaded by Paul Rothchild to join Butterfield’s band alongside rhythm guitarist Elvin Bishop. “Michael was a little intimidated by Paul, because Paul was a tough guy,” says Barry Goldberg. “He was a beer drinker; he wore a black leather jacket.” Butterfield’s pal Nick Gravenites was another tough guy, Goldberg says: “Those guys were scary. Not the kind you could small-talk with. If you said, ‘Hey man, how you doing?’ they just glared at you.”

Flying back to New York, Rothchild urged Jac Holzman to sign them to Elektra Records, despite the fact that the label had always shied away from electric music. Rothchild had only ever produced acoustic blues and folk for Holzman, and his initial attempts to capture the gritty Butterfield sound in the studio—and then in a faux-live setting at the Café au Go Go—were scrapped at considerable expense. At the third attempt Rothchild nailed the band’s debut, with its hometown anthem “Born in Chicago” and its versions of Muddy Waters’ “Got My Mojo Working” and Junior Parker’s “Mystery Train.”

Recommended by Rothchild, Grossman was instantly smitten, forging a bond with Butterfield that would last for the rest of his life. It was as though Butterfield grounded him in the Midwest that had spawned him, an earthy corrective to New York hype. It is even conceivable that the two men knew each other before Grossman left Chicago. “Before Albert was Albert, they were friends,” claims Butterfield’s son Gabe. “He, my dad, and Nick Gravenites were like the kings of Chicago. They had a lot of history.” Any misgivings Grossman might have had about straying from the folk path were rendered irrelevant by Dylan’s embrace of electricity—especially after Bloomfield’s performances on “Like a Rolling Stone” and the rest of Highway 61 Revisited.

Through Peter Yarrow, who was on the festival’s organizing committee, Grossman secured the group their Friday slot at Newport. They repaid his faith by cheering him on as he flailed around backstage with Lomax (though supposedly it was Sam Lay who pulled the two bears apart). The undignified showdown was, of course, symbolic of more than Grossman’s anger at Lomax’s condescension toward blue-eyed rhythm and blues: it was a head-on collision between folk tradition and rock revolution.

The folk community’s pervasive distrust of Grossman climaxed with Dylan’s electric set forty-eight hours later, aided and abetted by Bloomfield, Lay, and bassist Arnold. After that, there was no way back. As Pete Seeger, fellow folk activist Theodore Bikel and, yes, even Peter Yarrow knew in their bones, the utopian folk dream was over. “I would’ve plugged my guitar into Pete Seeger’s tuchus,” Bloomfield said uncharitably, “and put a fuzztone on his peter.” Like Grossman and Holzman—and like Dylan, indeed—Bloomfield knew that folk culture meant nothing if it refused to evolve. Folk’s future was electric, and the October release of The Paul Butterfield Band only confirmed it. Soon the band was experimenting still further with long jams—the “raga rock” classic “East-West” paramount among them—at such psychedelic ballrooms as the Fillmore in San Francisco. Bloomfield was America’s first white guitar hero, a counterpart to the deified Eric Clapton across the water.

In 1967, following the release of the East-West album, Bloomfield split from Butterfield to cofound hybrid blues and soul outfit the Electric Flag with Buddy Miles, Barry Goldberg, Harvey Brooks, and Nick Gravenites. (In due course Albert Grossman bagged them a $50,000 deal with Columbia.) With some of his new bandmates, the guitarist began using heroin. “I told Albert he needed to call a meeting,” says Goldberg. “One of the horn players had brought heroin into the band, and Albert knew that that was the one drug no one should mess with.”

Butterfield’s response to the loss of his guitar hero was to expand his lineup with a horn section, thereby moving the band’s sound away from Chicago blues toward a funkier, more soul-oriented style. Produced by John Court and sounding like a Fillmore version of the great Bobby “Blue” Bland—whose “I Pity the Fool” was one of its cover versions—The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw (1967) lacked the tight focus and urgency of the first two Elektra albums. “The further Butter moved away from the blues, the more he was moving away from what suited him best,” said Elvin Bishop, who quit the group in 1968. “The other stuff just splattered out: too much formlessness.”

Butterfield was undeterred, replacing Bishop with hotshot pretty-boy Howard “Buzzy” Feiten and adding trumpeter Steve Madaio to the existing horn section of trumpeter Keith Johnson and saxophonists David Sanborn and Gene Dinwiddie. He also made the decision to uproot the entire band to the East Coast after visits to Grossman’s lair convinced him that Woodstock would make a healthier base for the extended family his group had become. In late October 1968, the whole ensemble flew to New York with their partners and offspring. “We got off the plane from Chicago and went right to Albert’s offices,” says Lynne Naso, drummer Philip Wilson’s girlfriend. “Albert was business, and he was stern, and I sat outside and listened to raised voices. Paul was getting into the dollars—‘I’m not getting enough’—and Sanborn and Philip were telling him, ‘He’s not doing right by you; he’s manipulating you.’”

Things had cooled down by the time Butterfield and his wife, Kathy, moved into what Naso recalls as “the next house down from Bob Dylan on Ohayo Mountain Road.” Financially, matters were resolved to everybody’s satisfaction. “You’d pass the Butterfield guys on the street,” says drummer Christopher Parker. “It was like, ‘Oh, he got a new Mercedes—their new record must have come out.’” When the band wasn’t touring, its members were regular guests of the Grossmans. “The first time really sticks in my memory,” says Naso. “There was a late snowfall, and it was really chilly. We went to the house, which was like a mansion. We walk in the door, and a party is raging. There’s a lot of food and wine going around, and people are taking their clothes off. I didn’t want to share my boyfriend, but a lot of the girls were getting naked, and they would wander out of the room with some of the guys. I went for a wander and peeked in a room, and there was a very serious orgy going on involving a dog.”** For Naso, Grossman was the Mr. Big of Woodstock, an enigmatic chieftain pulling the strings that mattered. “He ran the show, and we got a ticket to go,” she says. “Paul went many years bickering back and forth with Albert, but somebody like him might not have made it without Albert.”

Bob Dylan in the White Room above the Café Espresso, August 1964 (photo by Douglas Gilbert)

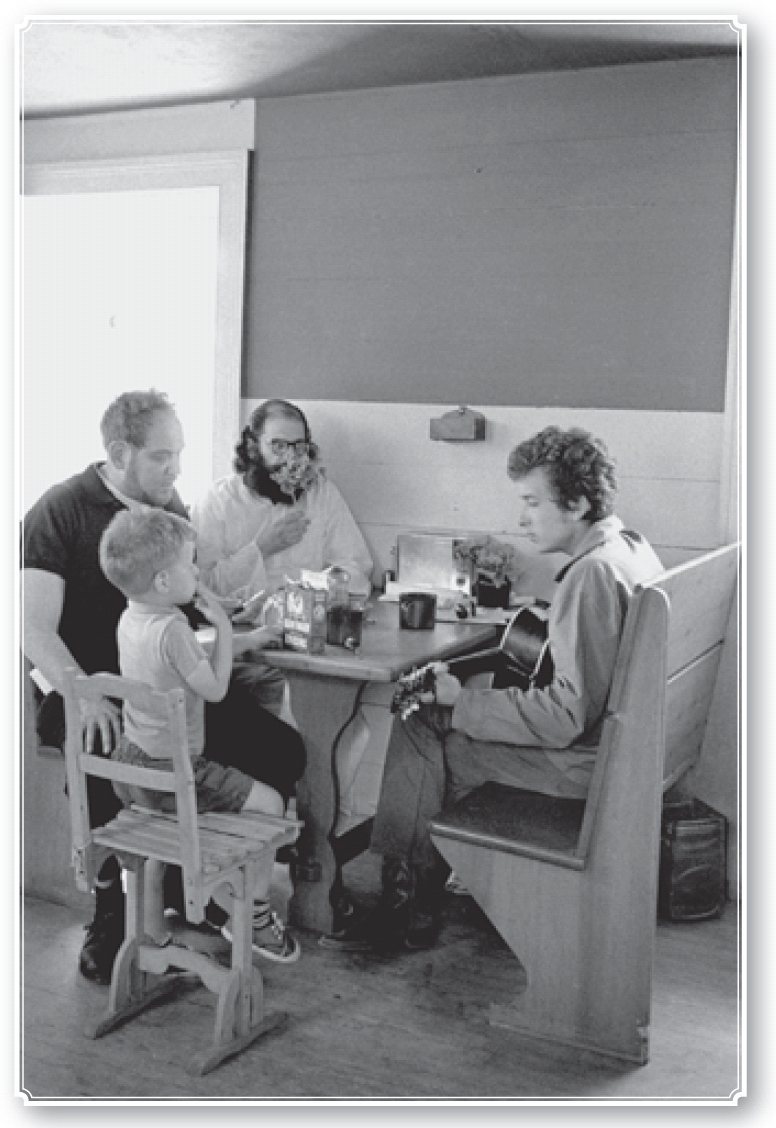

Dylan with Al Aronowitz and his son Myles (left) and Allen Ginsberg (with flower) in Albert Grossman’s kitchen, Bearsville, August 1964 (photo by Douglas Gilbert)

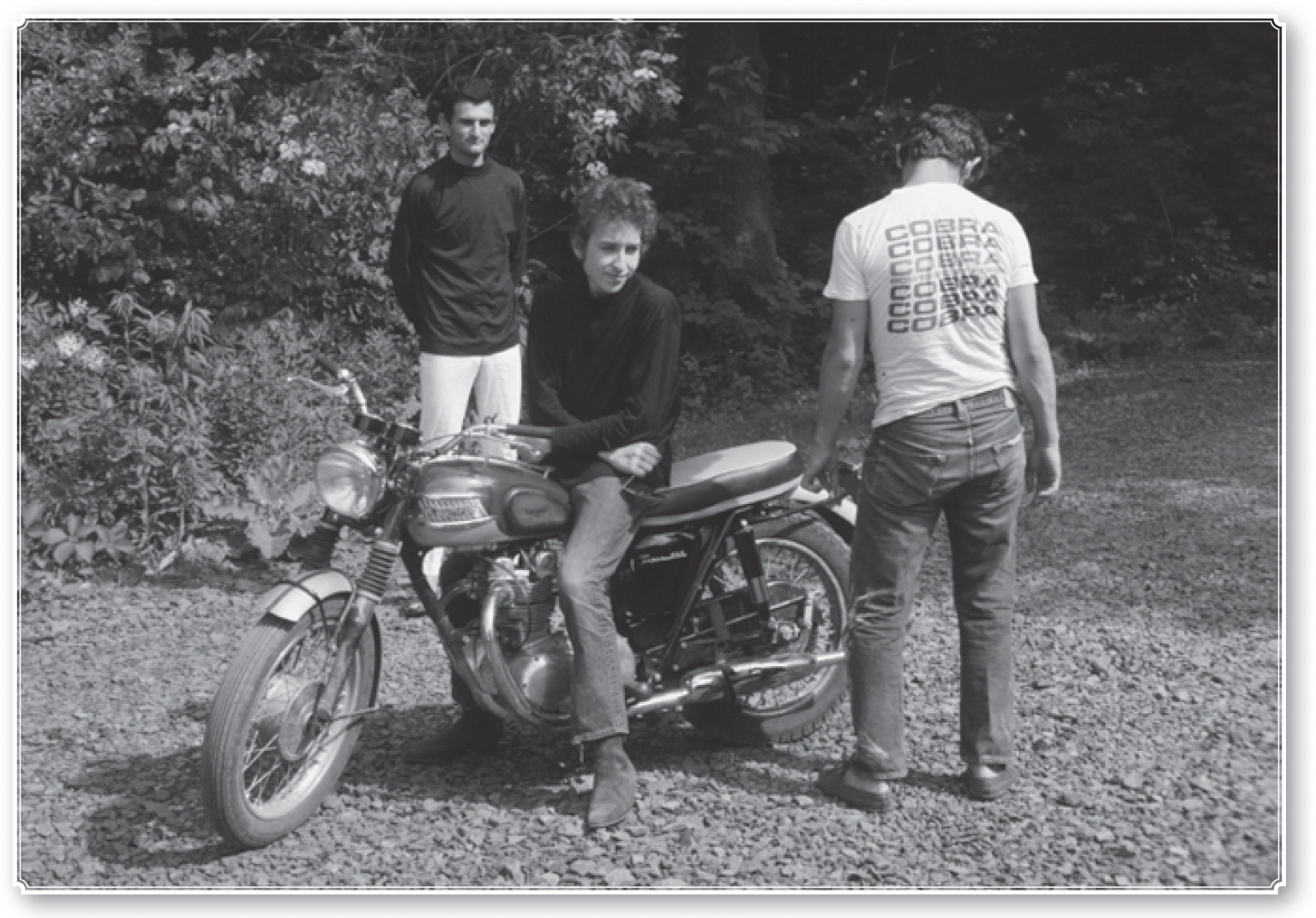

Dylan on his Triumph Bonneville with Victor Maymudes (left) and Bobby Neuwirth, Bearsville, summer 1964 (photo by John Byrne Cooke)

Dylan with Sara Lownds at the Shack, Vera Yarrow’s cabin on Broadview Road, winter 1965 (photo by Daniel Kramer)

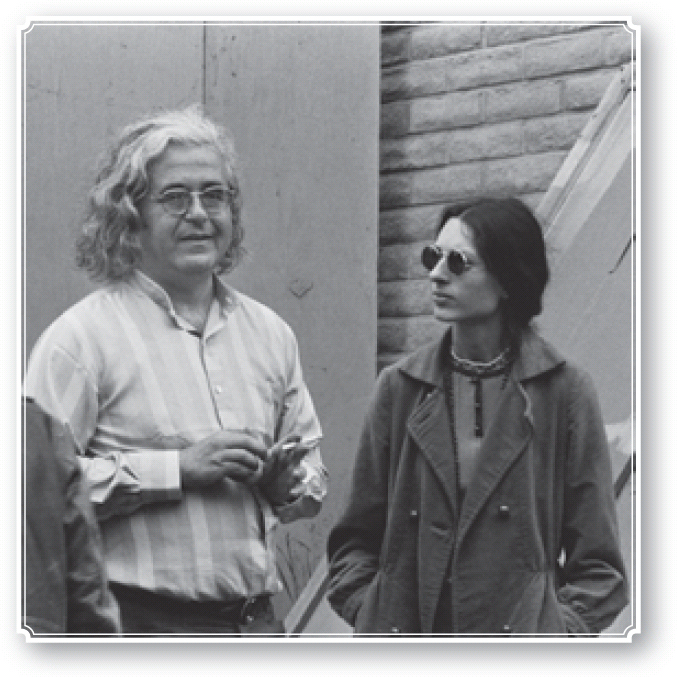

Albert and Sally Grossman at the Monterey Pop Festival in California, June 1967 (photo by Lisa Law)

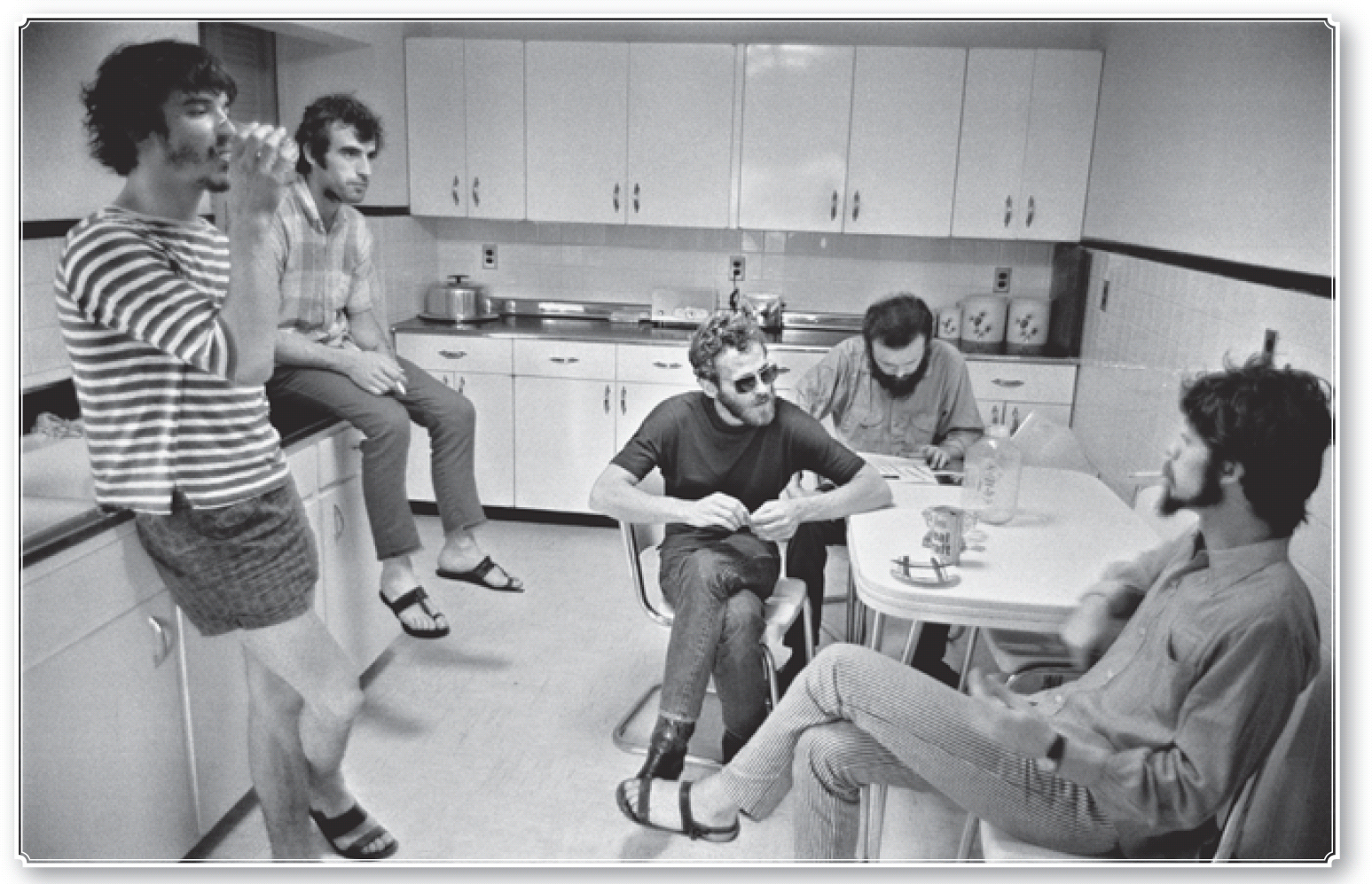

The Hawks (the Band) in the kitchen of Levon Helm’s and Rick Danko’s house off the Wittenberg Road, late summer 1967; left to right: Danko, Richard Manuel, Helm, Garth Hudson, and Robbie Robertson (photo by Elliott Landy)

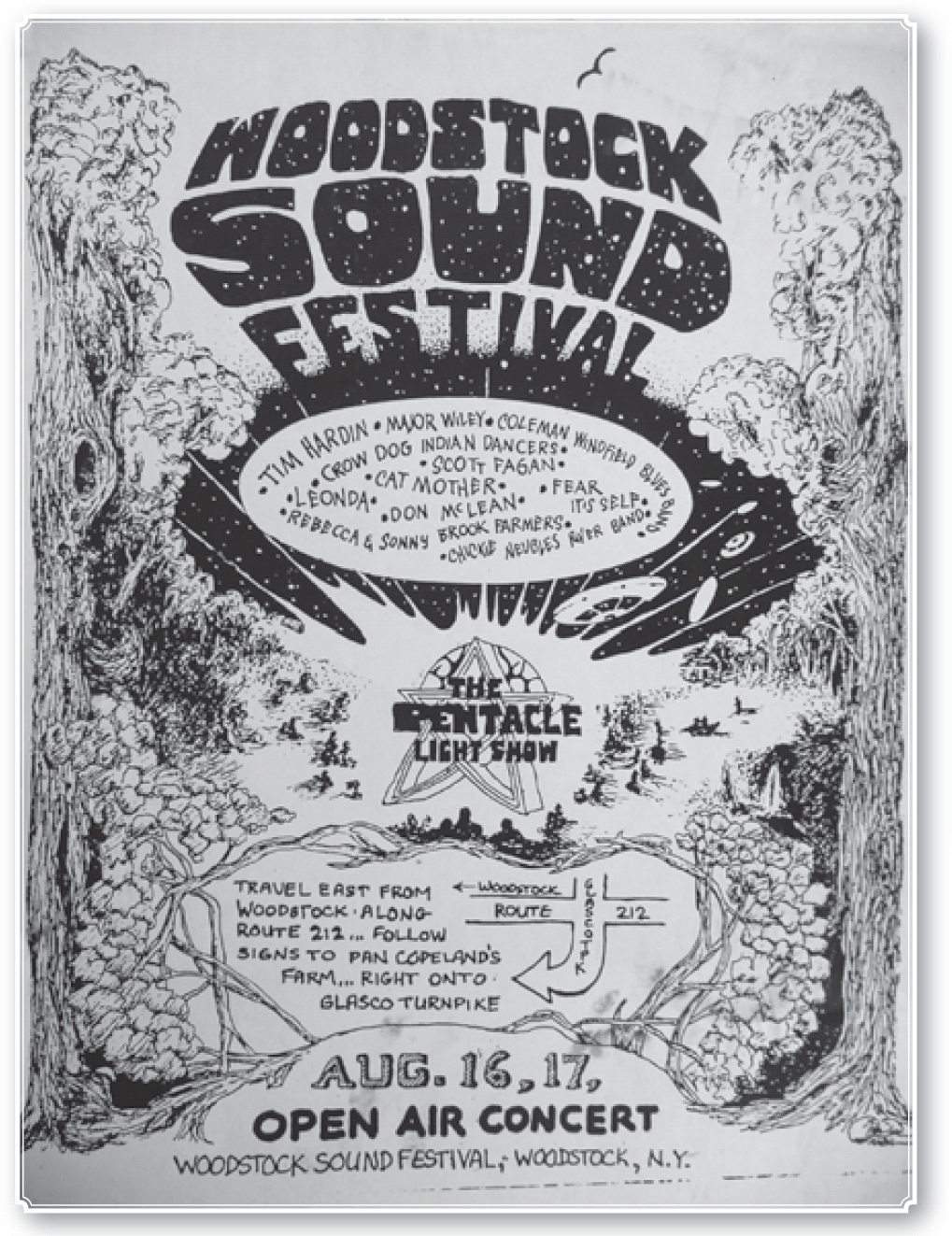

Poster for the Woodstock Sound Festival, August 1968 (courtesy of Fern Malkine)

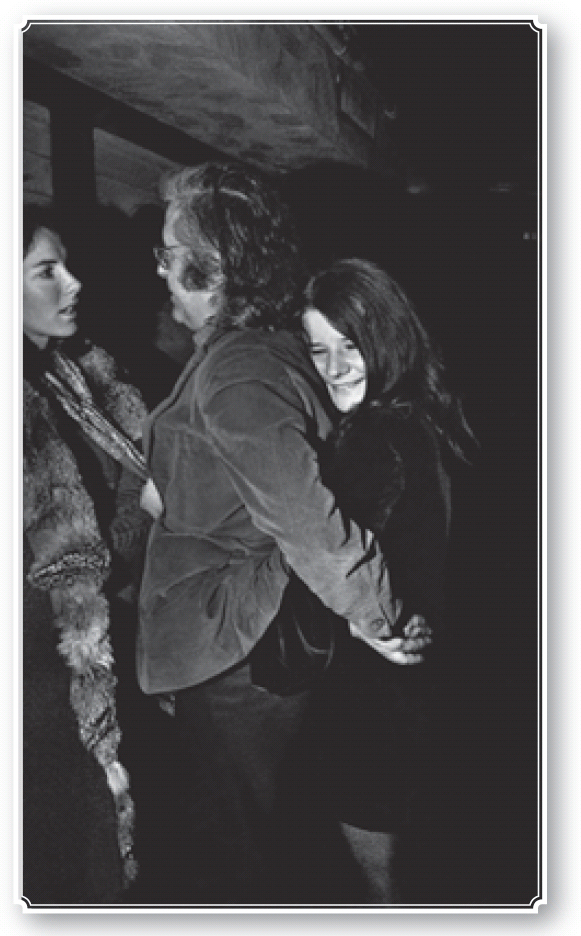

Daddy Albert with Janis Joplin, New York City, February 1968 (photo by Elliott Landy)

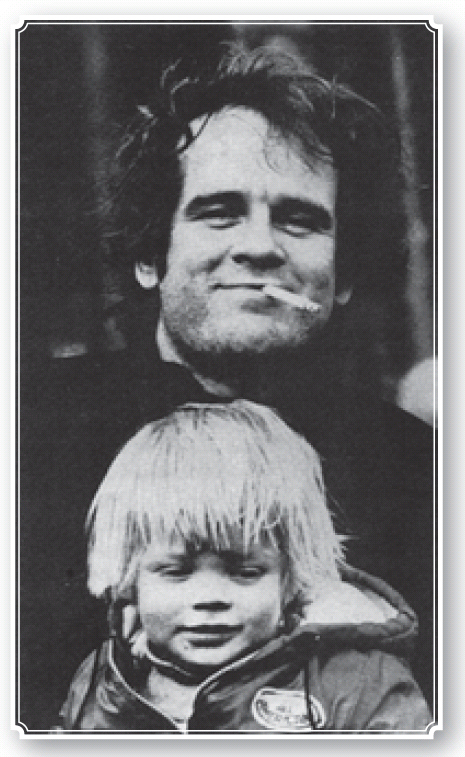

Tim Hardin and son, Damion, at the Onteora Mountain House, summer 1969 (Columbia Records publicity shot)

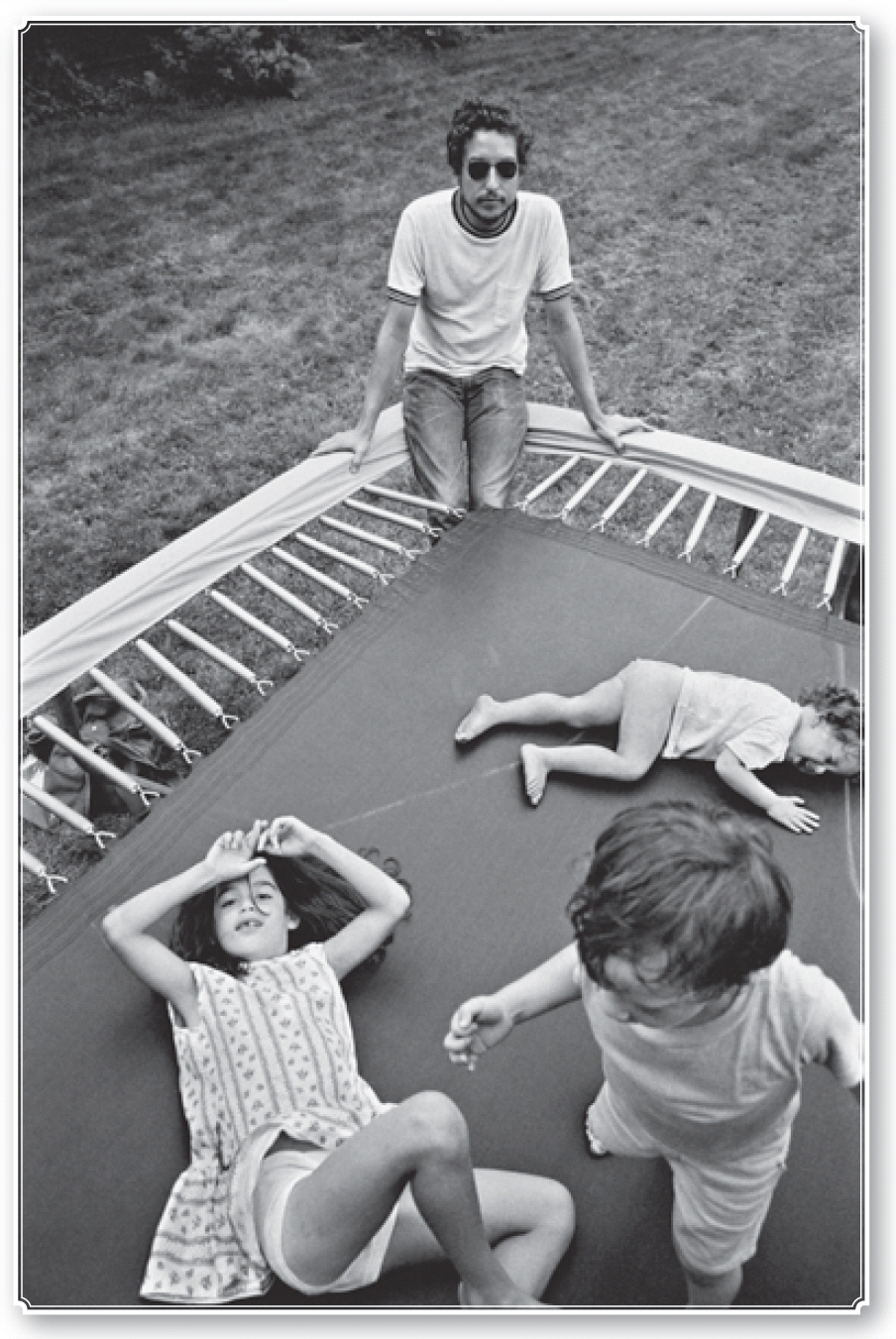

Daddy Bob on the trampoline with stepdaughter Maria (left), son Jesse (foreground), and daughter Anna, Ohayo Mountain Road, summer 1969 (photo by Elliott Landy)

Jimi Hendrix on horseback with roadie Eric Barrett at the “Shokan House,” Traver Hollow, summer 1969 (jimihendrixonline.com)

The Paul Butterfield Band in Woodstock, summer 1969; clockwise from top left: Gene Dinwiddie, Butterfield, Rod Hicks, Steve Madaio, Philip Wilson, Keith Johnson, Buzzy Feiten, David Sanborn (photo from the Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

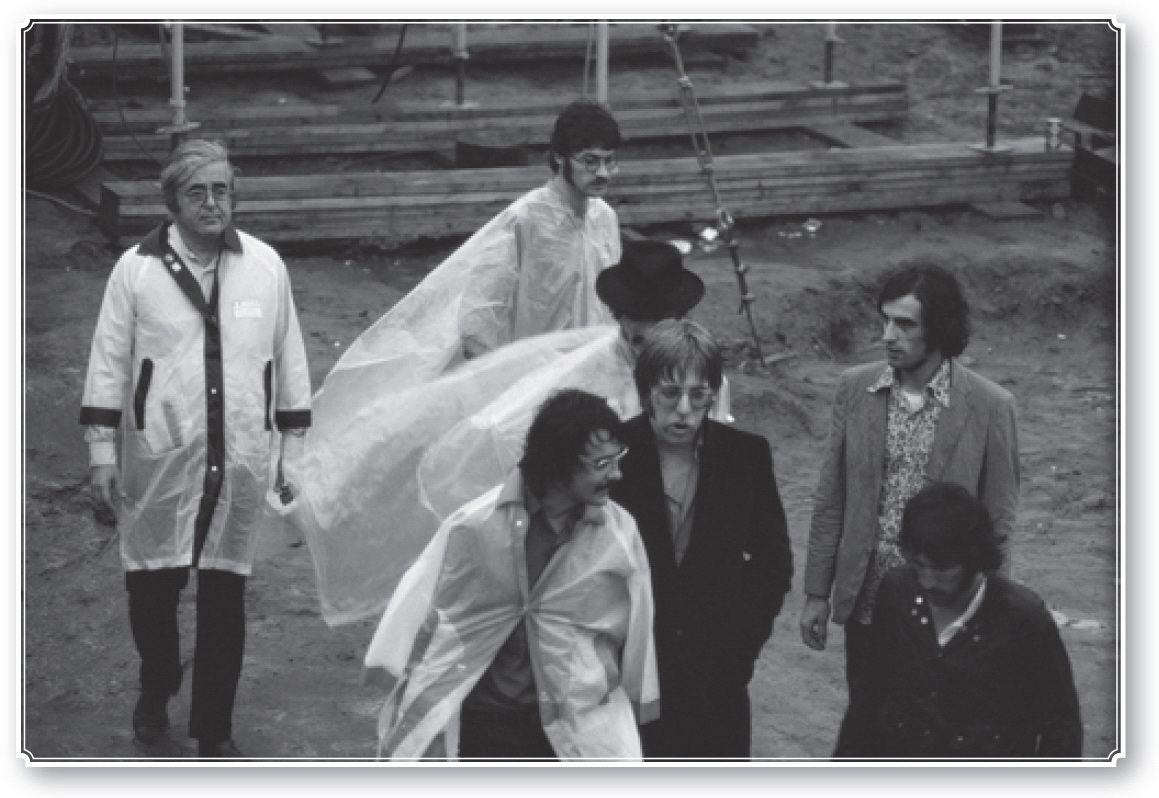

The Band and friends in the rain at the Woodstock festival, August 1969; clockwise from left: Albert Grossman, Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko (in hat), Richard Manuel, unidentified, Jon Taplin, and Bobby Neuwirth (photo by Lisa Law)

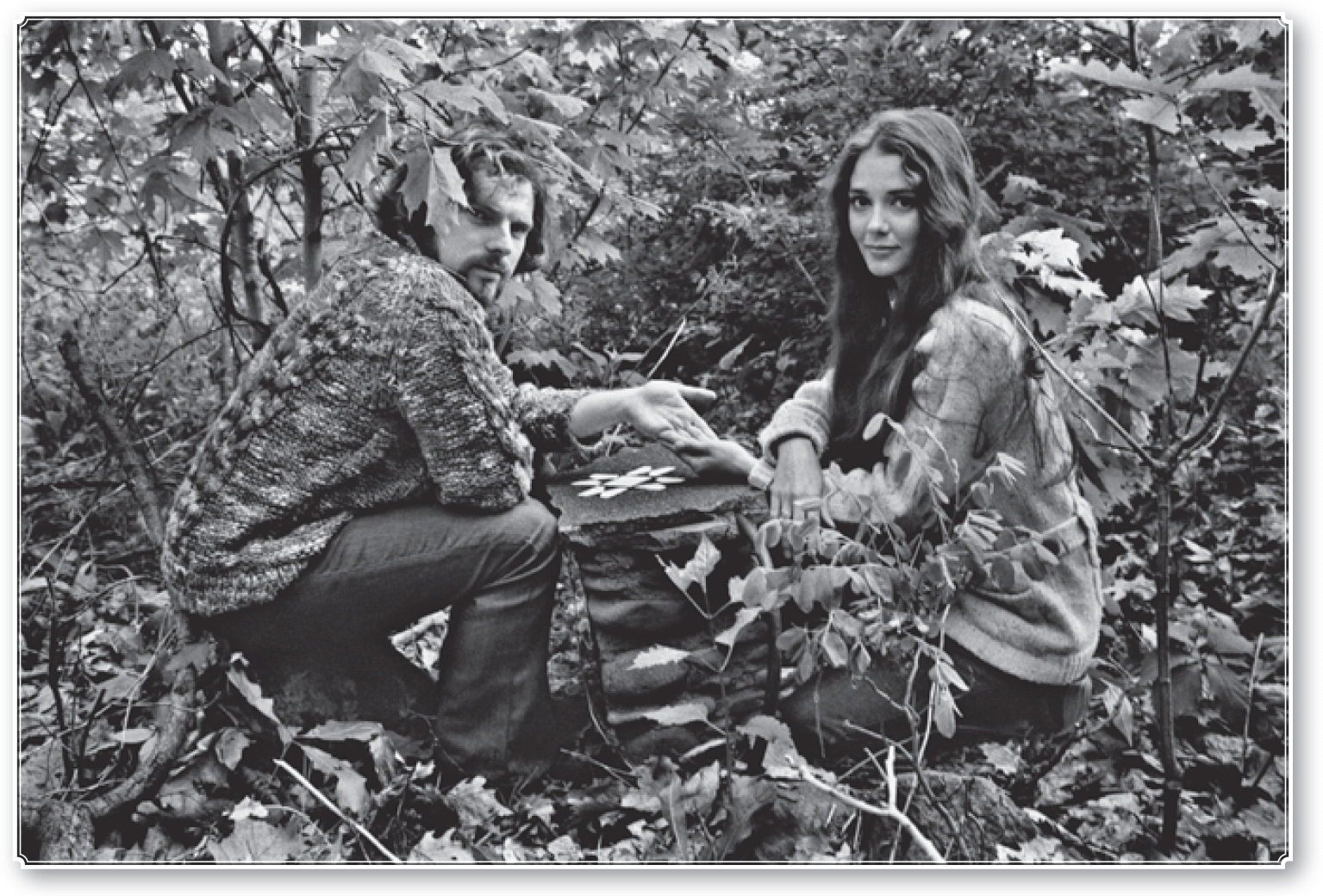

Van Morrison with Janet “Planet” Rigsbee behind their house on Spencer Road, Ohayo Mountain, summer 1970 (photo by Elliott Landy)

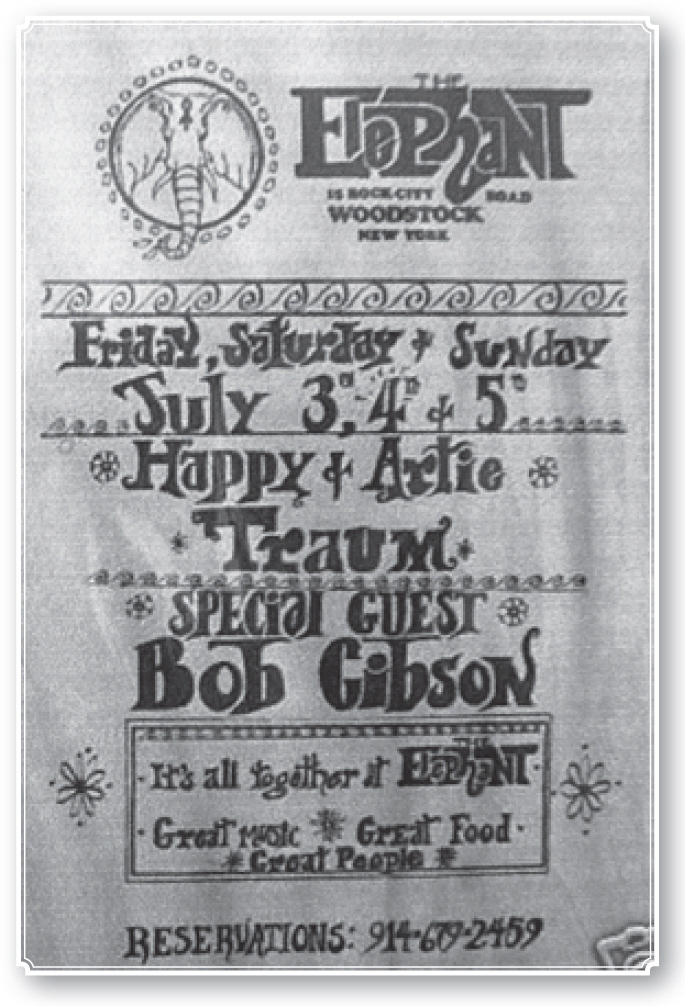

Flyer for Happy & Artie Traum show at the Elephant on Rock City Road, July 1970 (courtesy of Fern Malkine)

Karen Dalton in Woodstock, winter 1971 (photo by Elliott Landy)

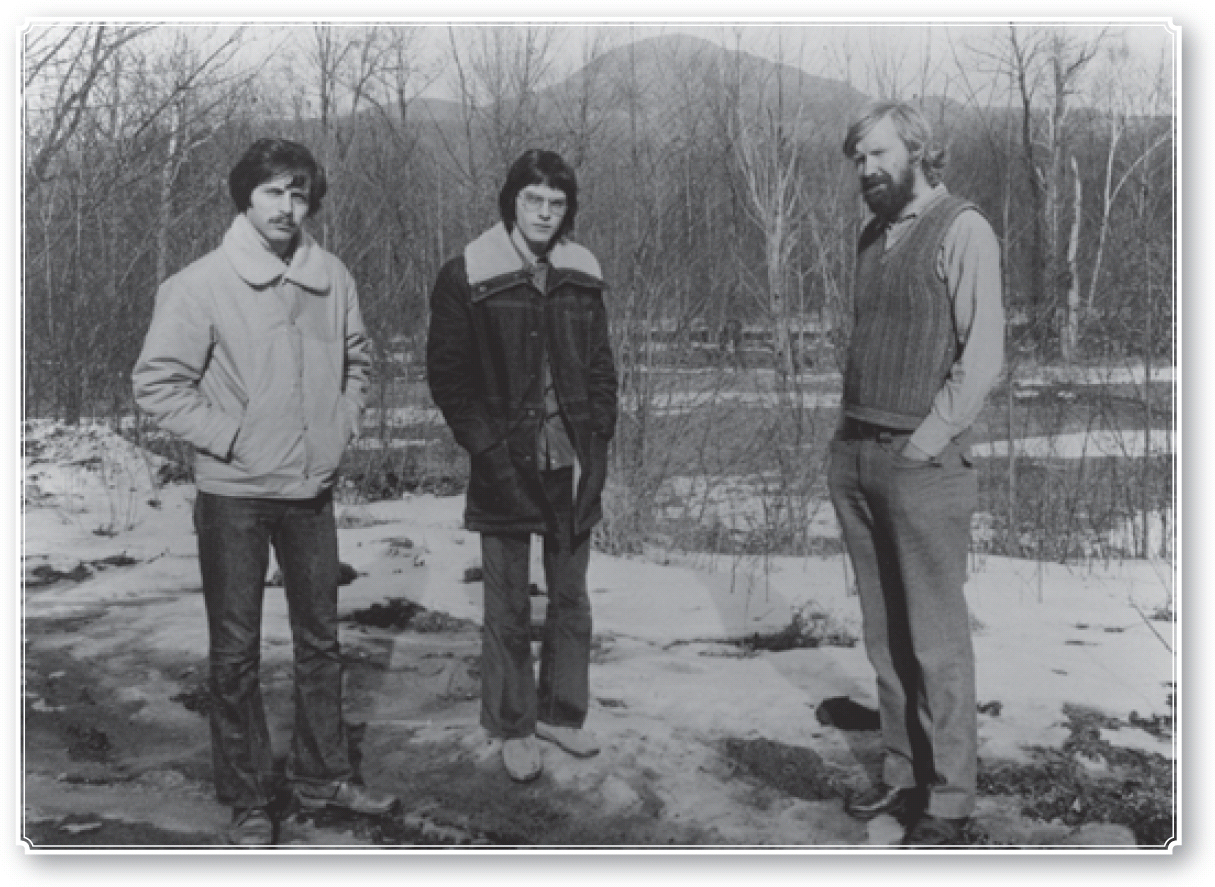

Borderline on Sickler Road, Lake Hill, winter 1973; left to right: David Gershen, Jon Gershen, and Jim Rooney (courtesy of Jon Gershen)

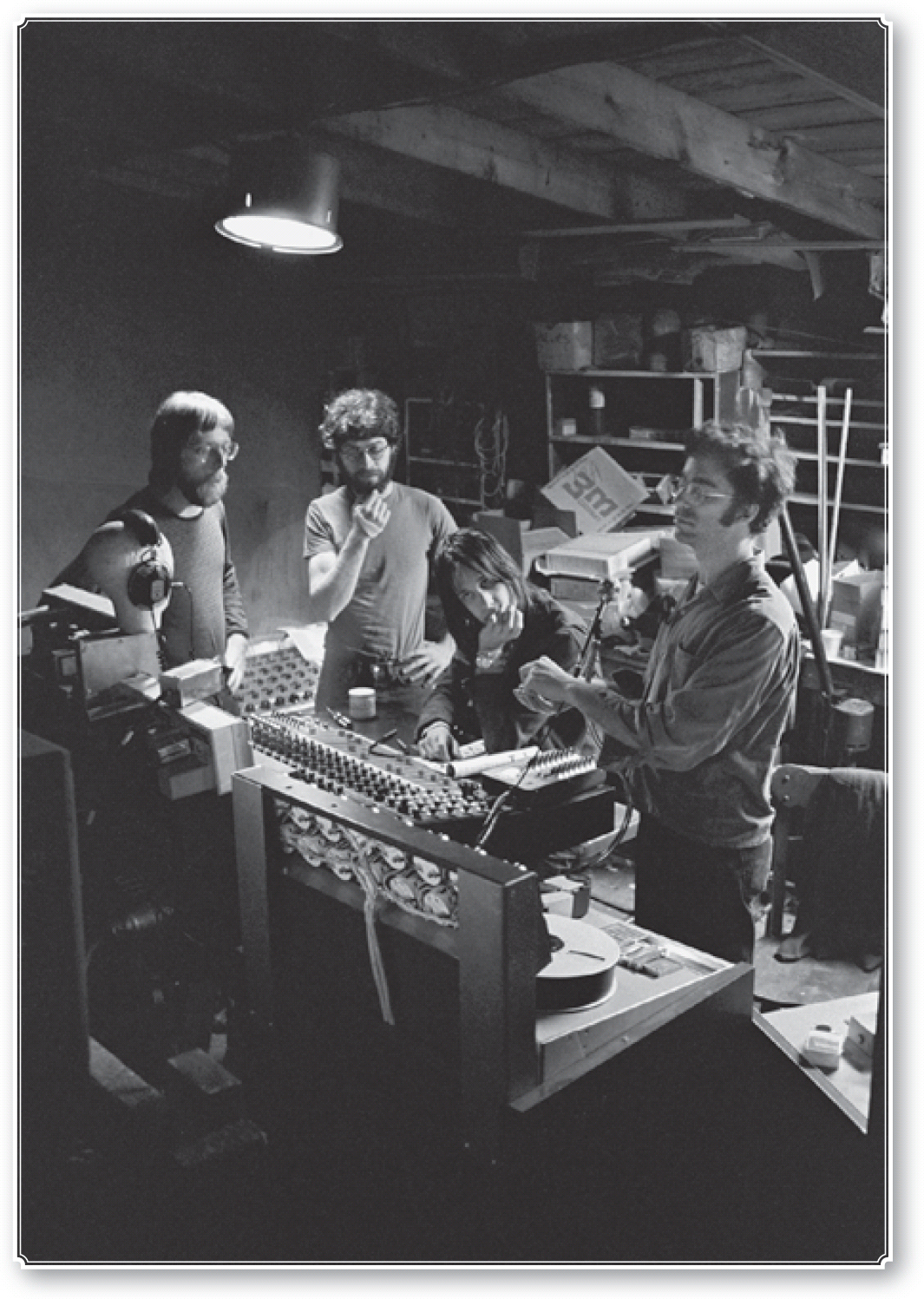

A weary Todd Rundgren at the board during the Band’s Stage Fright sessions, Woodstock Playhouse, early summer 1970; left to right: Jon Taplin, Robbie Robertson, “the Runt,” and a visiting John Simon (photo by John Scheele)

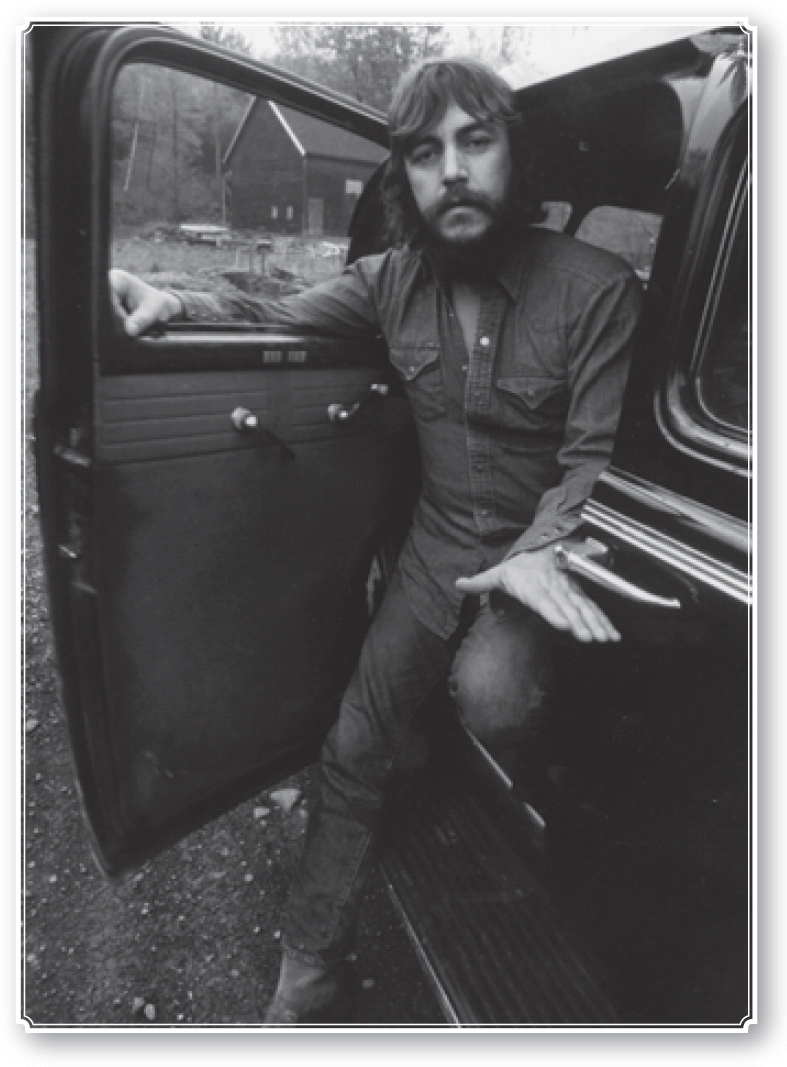

Bobby Charles at Turtle Creek, Bearsville, 1972 (Bearsville Records publicity shot)

John Holbrook at work in Bearsville’s Studio B, late seventies (photo by Shep Siegel)

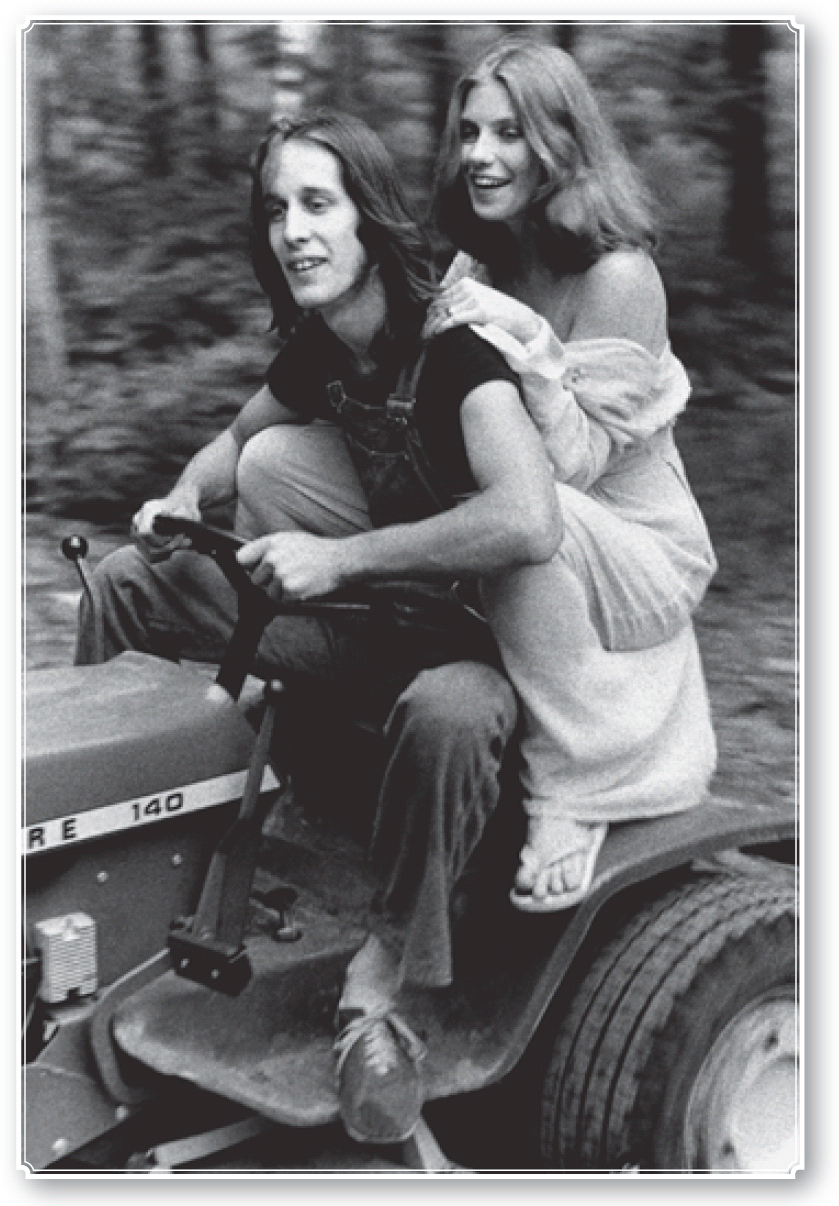

Todd Rundgren and Bebe Buell, Mink Hollow, summer 1975 (photo by Bob Gruen, www.bobgruen.com)

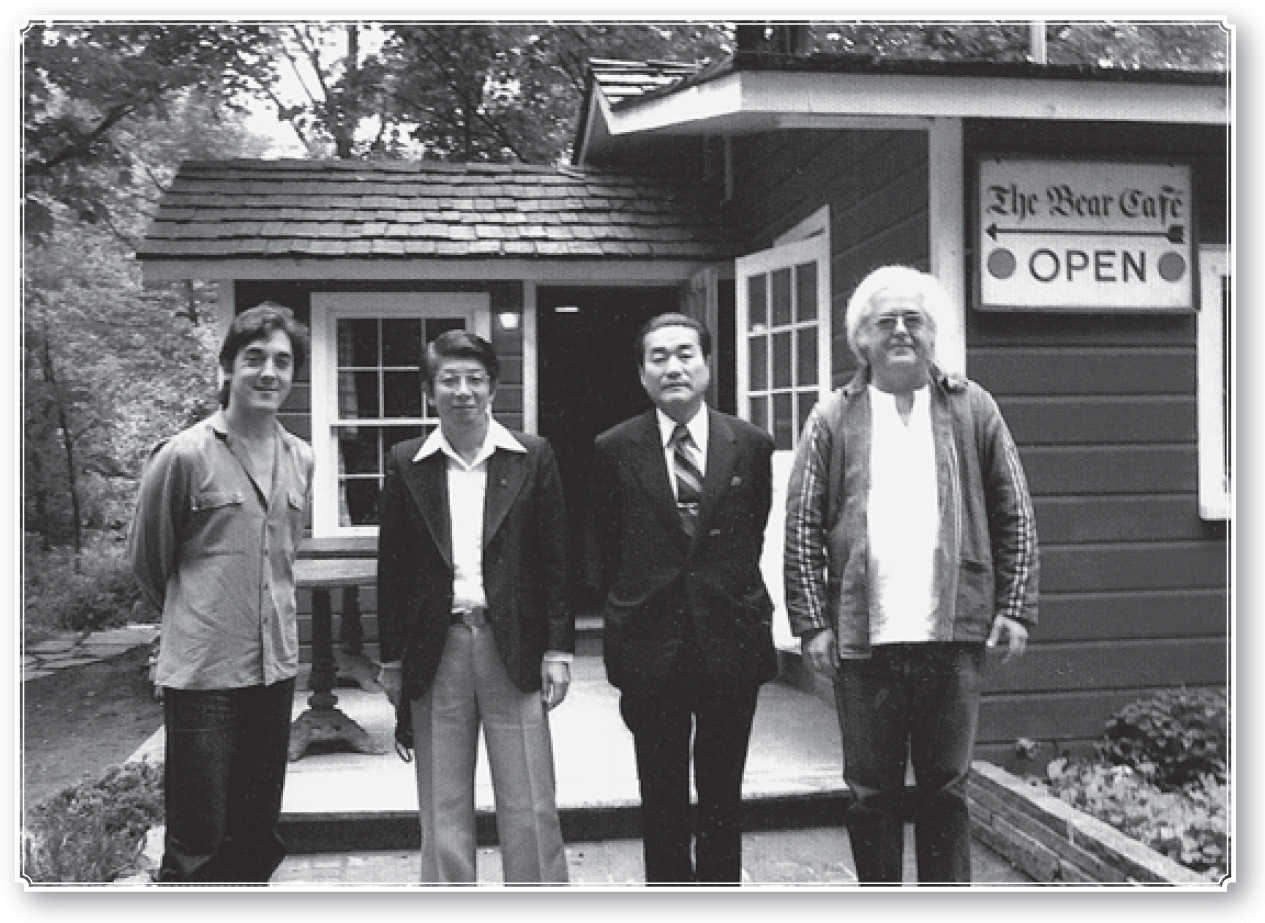

Albert Grossman (far right) with Ian Kimmet (far left) and executives from Yamaha, early eighties (courtesy of Ian Kimmet)

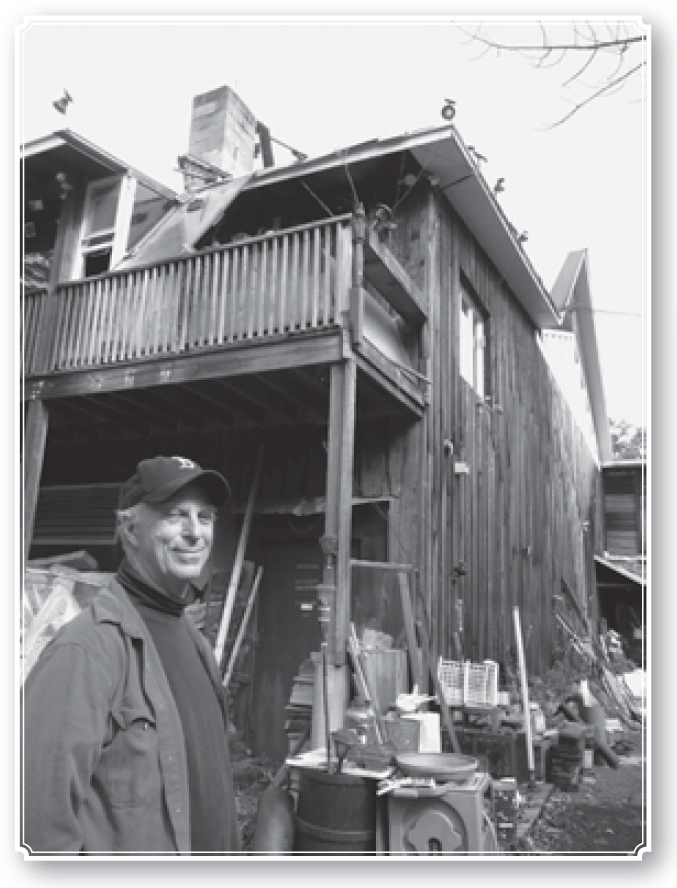

John Simon outside the old Bearsville studio, October 2013 (photo by Art Sperl)

Simi Stone and band at the Colony, Rock City Road, September 2013; left to right: Zachary Alford, Stone, Sara Lee (photo by Art Sperl)

The Bluegrass Clubhouse band at the Harmony Café, October 2013; left to right: Bill Keith, “Fooch” Fischetti, Brian Hollander, and George Quinn (photo by Art Sperl)

With most of them living at the Peter Pan Farm—where their rehearsals took place—the Butterfield band was now a formidably funky outfit. “Paul brought a lot of the great players to town for the first time,” Levon Helm remembered. “Those guys came in and made the town a more musical place.” The group played the Woodstock Sound Festival in the early summer of 1969, frequently jamming with other local musicians at the Espresso, the Elephant, and the Sled Hill. “Most of that band was musically literate,” says Graham Blackburn, one of those who jammed with them. “It was such a big organization that they could never really play around Woodstock, but they would all play individually. Different people would show up at the Sled Hill.” Butterfield’s harp even influenced the teenage Jim Weider. “It was the way he bent the notes,” the guitarist says. “It was his attack.”

In August the band played at dawn before Sha Na Na’s and Jimi Hendrix’s sets at Woodstock, though thanks to Grossman they weren’t in the film and only the execrable “Love March” made it onto Atlantic’s soundtrack album. For 1969’s Keep on Moving, Jac Holzman paired the band with soul producer-songwriter Jerry Ragovoy, and the ultra-funky result knocked Pigboy Crabshaw [and subsequent In My Own Dream] into a cocked hat. “That horn-section band was one of the happiest times of my father’s life,” says Gabe Butterfield. “He was on fire.”

By 1971, when the group released a de rigueur live album—recorded at the Troubadour in L.A. with Todd Rundgren at the controls—their personnel had changed again. Meanwhile the Butterfields had found a measure of domestic bliss with their new baby, Lee, in a house out on Wittenberg Road. The group’s final Elektra album, Sometimes I Just Feel Like Smilin’—with the group posed against a mountain skyline, referencing Elliott Landy’s group shot for Music from Big Pink—included an instrumental called “Song for Lee.”

IF GROSSMAN WAS frustrated that he couldn’t make a bigger star of Butterfield, he had no such problems with Janis Joplin. The careers of the two musicians, rooted in blues, ran on broadly parallel lines: they shared Fillmore bills during the first days of Big Brother, and both were infatuated by horn-driven R&B. Among Joplin’s many love affairs was one she conducted in 1969 with Gene Dinwiddie; she even jammed with Butterfield’s band while visiting Dinwiddie on the Peter Pan Farm. The following March she recorded the on-the-road song “One Night Stand” with them in Los Angeles.

Unlike Butterfield, whose primary voice was his mouth harp, Joplin was an indisputably powerful singer. Combined with her spunky image—all feather boas and bell-bottoms—her hair-raising voice made her what West magazine called the “shaman mama” of the new rock era. In Myra Friedman’s words, “[she] was actually being merchandised as the symbol of everything that was against the very idea of merchandising.” As with Dylan, everyone wanted a piece of her. “Everywhere I go, the people wanna make some time with me,” she sang on “One Night Stand.” “That’s okay, if the next day I can be free.”

Grossman did what he had done with his first superstar: he protected her, often bringing her up to Bearsville to keep an eye on her. He was also determined to up her game artistically: managing exceptional musicians like Butterfield and the Band made him ever less tolerant of Big Brother’s shortcomings. “Albert wanted predictable technical competence, and that wasn’t what Big Brother was about,” says John Byrne Cooke. “He didn’t want to deal with the vagaries of whether the band’s magic was going to work one night or not.” Joplin needed little persuading that a better band would help her to move beyond mere psychedelic freakery. “They didn’t want to learn any new material, whereas she wanted to be better,” says songwriter JoHanna Hall, whom Joplin had befriended in New York. “She wanted to grow.” More than anything, she aspired to the same big-band soul sound that consumed Butterfield; she knew Big Brother would never get close to the funky precision of, say, the Stax house band. “I love those guys more than anybody else in the world,” she told writer Michael Lydon. “But if I had any serious idea of myself as a musician, I had to leave. Getting off, real feeling, like Otis Redding had, like Tina Turner, that’s the whole thing of music for me.”

Elliott Landy saw the changes coming after he was assigned to do a Big Brother shoot in New York. “They were as important as she was, but the magazine wanted me to focus on her,” he says. “It didn’t strike me as right.” In an essay on Joplin in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock ’n’ Roll, rock critic Ellen Willis noted that “the elitist concept of ‘good musicianship’ was as alien to the holistic, egalitarian spirit of rock and roll as the act of leaving one’s group the better to pursue one’s individual ambition was alien to the holistic, egalitarian pretensions of the cultural revolutionaries.” Within days of quitting Big Brother—whose loyal though equally addicted guitarist Sam Andrew she retained—Joplin was putting together a new group, complete with a three-piece horn section. “We were all crushed,” fellow guitarist James Gurley remembered. “And the scars from that have lasted until this day.”

Gurley was certainly not alone in seeing the firing as a betrayal of the original Haight-Ashbury spirit—and resenting the covert anti–Big Brother propaganda that seeped out of Grossman’s office. “The idea was that they were all pretty lame,” says Donn Pennebaker. “But the fact is that they suited her and weren’t competitive with her.” Perhaps feeling guilty for breaking up the band, Grossman halfheartedly offered to help Big Brother after Joplin’s departure, even packing John Herald off to San Francisco to sing with them. “[Herald] was very much a typical Albert Grossman kind of folk act,” said drummer Dave Getz. “He came out and played with us one day, and [he was] so completely the wrong person for Big Brother . . . it really convinced me that Albert just never even had any idea what we were about.”

“Janis was moving into a bigger league and saying good-bye to her Haight-Ashbury boys,” says Peter Coyote. “She rebranded herself, but leaving them was like a divorce from her authentic roots.” Invited to New York—where she installed them gratis at the Chelsea Hotel—Coyote and Emmett Grogan saw how desperately she wanted to stand as an equal alongside her African American peers. “We were walking past the Fillmore one night, and Janis went off on how great Mavis Staples was,” Coyote remembers. “I said, ‘Well, Janis, you’re the one who’s got top billing.’” To him, on scorching versions of songs by Jerry Ragovoy and Van Morrison’s old mentor/nemesis Bert Berns, she worked too hard to prove her soul chops.

When Grossman learned definitively that Joplin was using heroin, he turned to an old ally to chaperone her through her one and only tour of Europe. “Bob Neuwirth was with us for part of it,” says John Byrne Cooke. “I think Albert wanted to have another pair of eyes around. He thought Bobby—not having to do all the things I had to do as road manager—could hang out with Janis and get a better sense of where she was at.” With Neuwirth on board, Joplin and her entourage—which now included actor Michael J. Pollard, fresh out of 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde—replicated the scalding wit that Dylan and his cronies had patented a few years earlier. In London, where she played the Royal Albert Hall in front of a celebrity-studded crowd, Ian Kimmet was recruited as yet another “pair of eyes” to mind Joplin. When Richard DiLello of Apple Records showed up at her hotel, she was, says Kimmet, “hanging all over him and saying, ‘Did ya bring me something, babe?’”

“Janis was certainly enabled, but back then we understood so little about alcohol and drug problems,” says John Byrne Cooke. “The whole business of codependency and enabling, none of that was in the language.” As Myra Friedman wrote, “there was only the chasm of non-communication filled up by the argot of hipness.” Some believed that, as with the Electric Flag, Grossman failed to confront Joplin as he should have done, even if ultimately he cared more about her than he’d ever cared about Mike Bloomfield—or even, perhaps, about Bob Dylan. When it later transpired that he had, in June 1969, taken out a life insurance policy paying $200,000 in the event of her accidental death, it seemed to confirm the cold-blooded pragmatism of the man she trusted and loved.

“Janis was very insecure,” says JoHanna Hall. “She would say to Albert, ‘When no one wants me anymore, will you give me a job in the office?’” If she couldn’t reach Grossman in snow-bound Bearsville, she became as frantic as an abandoned child, protesting that he would never treat the Band or Butterfield like that. “She was a troubled being,” says Peter Coyote. “And part of what troubled her was the difference between the throwaway Port Arthur pimpled girl and the image she had created.” Joplin’s relentless sexual liaisons were attempts to convince herself she was prettier than she believed herself to be. Strongly attracted to men who quickly dumped her, she seemed to be trapped in a cycle as addictive as her abuse of booze and drugs. As she only half-jokingly told Dick Cavett in a TV interview, “[men] just always hold up something more than they’re prepared to give.” There was a painful paradox in Joplin’s uninhibitedness: as Ellen Willis noted, “women endowed the idea of sexual liberation with immense symbolic importance . . . yet to express one’s rebellion in that limited way was a painfully literal form of submission.”

Joplin was becoming almost as insecure about her music as she was about her looks. Though she now at least had a band capable of performing the soul material she loved, she was terrified that African Americans would dismiss her as phony. A poorly received performance at Memphis’s second Stax-Volt Yuletide Thing in December 1968—with Mike Bloomfield sitting in—confirmed her worst fears: the new stars of Southern soul at best tolerated her, at worst resented her infiltration of their musical patch, their hostility to honkies stoked by the assassination in April of Martin Luther King in the very motel where Joplin was staying.

With the L.A. sessions for I Got Dem Ol’ Kozmic Blues Again, Mama (1969), Joplin came closer to realizing her goals on versions of Jerry Ragovoy and Chip Taylor’s “Try (Just a Little Bit Harder)” and the Bee Gees’ “To Love Somebody.” An aching interpretation of the Rodgers & Hart masterpiece “Little Girl Blue” seemed to pour from the pain inside her, a cry from the heart to anyone who was listening.**

At the Woodstock festival, Yasgur’s massed hippies weren’t as gaga for Joplin’s ersatz soul review as she had hoped. When Snooky Flowers took over the vocals for a Stax-by-numbers version of Otis Redding’s “I Can’t Turn You Loose,” many of them wanted their old Haight sister back. It didn’t help, either, that Sly & the Family Stone came on directly after her at three-thirty a.m. and all but obliterated any impression she had made. At the end of the year she disbanded Kozmic Blues, retaining bassist Brad Campbell and new guitarist John Till but dispensing altogether with the horn section. What she (and Grossman) wanted more than anything was a crack unit of studio-quality players who could help her make a great album. In came Ken Pearson (organ) and Clark Pierson (drums), who’d played with Till in his own Full Tillt (sic) Boogie Band, and Richard Bell, an exceptional piano player who’d worked with Till in Ronnie Hawkins’s Hawks. Almost all of them were based in Woodstock, where Joplin often rehearsed with them.

“I stole Richard from Ronnie,” admits Michael Friedman, whom Grossman had asked to scout for new musicians. “He was just off-the-hook great, a killer piano player, so after a show I asked if he wanted to join Joplin’s band. Ronnie comes over to me, pushes me against a wall, and says, ‘You tell Albert I’m sick and tired of being his fuckin’ farm team!’” Worse for the Hawks’ subsequent career was his confrontation of Grossman himself. “I’ll whip enough piss out of you to scald a hog,” he yelled while pulling on Albert’s pigtail. It was probably no coincidence that, in his own words, Hawkins’ “concert dates dried up” after that.

Joplin lopped the second l off of Tillt, and the group became Full Tilt Boogie. She was finally satisfied with her backing band—happy enough, indeed, to try to get her life in some kind of order. “She bought a house in Larkspur, and she was pulling it all together,” says Maria Muldaur. She was also closer than ever to her manager. Even Sam Andrew, who’d been given the heave-ho, acknowledged Grossman’s nurturing side. “I knew that he really liked Janis,” he said in 1998. “He really understood her.” Ian Kimmet says that years later, when critics compared singers like Pat Benatar to Joplin, Grossman would explode: “He’d say, ‘What the fuck are they talking about?!’”

John Byrne Cooke watched the deepening relationship between Joplin and Grossman as Full Tilt came together in the spring of 1970. “She never felt she didn’t have his ear,” he says. “They were like hangout buddies.” Joplin’s trust in Grossman was so implicit that for about five months she was even able to give up heroin. “She not only felt that her business was being handled properly,” Cooke says, “but she knew more about it because she talked about it with Albert.” Grossman was intent not only on helping Joplin but on improving her image. A Rolling Stone profile had compared her to the tragic Judy Garland; Grossman wanted people to know what a life force she was. “She was a reader, she was intellectual, she was funny,” says writer David Dalton, whom Myra Friedman invited to meet her. As he walked into the East Fifty-Fifth Street office, Joplin was perched on the edge of a desk strumming an acoustic guitar and singing a wistful country song of love and wanderlust cowritten by Kris Kristofferson. “Of course I know now that ‘Me and Bobby McGee’ wasn’t her song,” Dalton says, “but to hear her sing it then was an astounding thing.”

The British-born Dalton hit it off with Joplin and was invited to join her as one of two Rolling Stone reporters on the “Festival Express,” a train ride across Canada boasting an all-star mix of Americans and Canadians (and thereby making one of Bob Dylan’s pipe dreams come true). “I was a card-carrying hippie in the sense that I didn’t drink,” he says. “But Janis insisted on it: two double Jack Daniels at eight in the morning.” Other entertainers on the train—the Band, the Grateful Dead, Delaney & Bonnie & Friends, and Ian & Sylvia’s Great Speckled Bird—followed suit: the train was a virtual incubator of alcoholism. But it was also a magical last gasp of the communal-musical Woodstock spirit. “We left our egos at the train station,” reminisced the lissome and quavery-voiced Sylvia Tyson, whose husband introduced Great Speckled Bird’s cover of “Tears of Rage” as “a song Bob Dylan wrote about his kids.”

Contagious jam sessions took place at all hours of the day and night. “One of the cars became very quickly devoted to electric music, whereas the other one was the acoustic car,” says John Byrne Cooke, who doubled as participant and tour manager. “Rick Danko and I would trade Hank Williams songs. Richard Manuel said to me, ‘You can’t sing like that—you’re a road manager!’” Joplin may never have been happier than she was during renditions of old bluegrass and mountain gospel songs led by the pickled Danko and accompanied by the Cheshire-cat-grinning Jerry Garcia. If she looked and sounded ragged at the riot-disrupted opening show in Toronto, by Winnipeg and Calgary she and Full Tilt had truly hit their groove.

Back in California, work commenced on a new Columbia album whose motif was an alter ego that Joplin had established for herself: “Pearl,” a good-time gal and voracious man-eater, the extroverted public face of the lovelorn self-doubter from Port Arthur. With Paul Rothchild, who’d produced not only the Butterfield band but the Doors, she set to work on a batch of strong songs that included “Cry Baby” and “Me and Bobby McGee.” The arrangements were slick, the playing of her Canadian henchmen tight and muscular.

Nowhere did that playing sound more fluent or funky than on “Half Moon,” a song coauthored by Joplin’s friends John and JoHanna Hall. “She was always looking for new material,” says JoHanna, who had reviewed the Kozmic Blues album in the Village Voice. “As she was leaving one night, she stood in the doorway and said, ‘Why don’t you two write me a song?’ I said, ‘Me?’ She said to me, ‘You’re a woman; you’re a writer. Write me a song!’” Along with two soaring Jerry Ragovoy classics—“My Baby” and the prophetic “Get It While You Can”—maverick soul man Bobby Womack stopped by the Pearl sessions with his song “Trust Me,” later claiming it was a ride in his car that inspired an off-the-cuff novelty Joplin wrote with Bobby Neuwirth and poet Michael McLure. As flippant as it was, the a cappella “Mercedes Benz” perfectly articulated the escalating expectations of rock’s new elite.

As the sessions began, Joplin was in a positive frame of mind. She’d even fallen in love with Berkeley student Seth Morgan. “She was talking about getting married,” says Michael Friedman. Halfway through the sessions, however, Joplin reacquainted herself with heroin. “She was all excited about her wealth and said she might buy her own town in Texas,” says Ed Sanders. “But I could see fifty or sixty gold bracelets around her wrists and forearms that were hiding her tracks.” “Mercedes Benz” was the last song Joplin recorded before she overdosed and died at Hollywood’s Landmark Hotel on October 4, two weeks after the death of Jimi Hendrix. She had been due to record her vocal for Nick Gravenites’s “Buried Alive in the Blues” the next day.

Grossman, who later claimed he had no idea she was back on smack, was at home in Bearsville when he got the call. “I can hear his voice as I’m talking now,” says Michael Friedman. “He just said, ‘Michael, Janis is dead.’ I was breathless. I jumped in my car and went over to his house. There was nobody else there. And I saw a side of Albert I had never seen before. He was so deeply wounded. He was genuinely in touch with all of his feelings. It was a very moving moment for me.”** Grossman immediately flew out to L.A., where a series of wakes was held at the Landmark. Neuwirth and Grossman’s right-hand-man Bennett Glotzer were in attendance, as was Kris Kristofferson, whose “Bobby McGee” would top the Billboard singles chart in the New Year. Pearl itself would reach number 1 and remain there for nine weeks.

In a will signed on October 1, Joplin had left money for two parties to be held in the event of her death. One was in San Anselmo in California, the other in a Bearsville restaurant that Grossman had recently opened near his home. “Bob Neuwirth and Rick Danko were walking around like hosts,” says JoHanna Hall. “They were asking people, ‘Is everything alright at this table?’” Also present was David Dalton, whom Myra Friedman had invited to the party. Grossman demanded to know who he was. “I said, ‘Albert, I wrote the article about Janis in Rolling Stone,’” he recalls. “He said, ‘How do I know that?’ I said, ‘Albert, why would I pretend to be him?’”

The belligerence was a displacement of Grossman’s grief. “He was devastated,” says Ronnie Lyons. “He kept saying, ‘I’m outta the business.’”

![]()

* The only real account we have of Lomax’s introduction came from the late Paul Rothchild, who told Eric Von Schmidt and Jim Rooney that the revered blues scholar had spoken words to the effect that there “used to be a time when a farmer would take a box, glue an axe handle to it, put some strings on it, sit down in the shade of a tree and play some blues for himself and his friends,” whereas now “we’ve got these guys, and they need all this fancy hardware to play the blues.”

* In a muckraking item for the New York Journal-American, Walter Winchell wrote about “British rock and roll stars and touring recording people” gathering at a Woodstock hideaway where they were ferried around in Rolls Royces and treated to the favors of young women. One can only assume he was referring to Grossman’s house, though it may have been Mike Jeffery’s.

* Among the outtakes from the Kozmic Blues sessions was a curiously up-tempo rendition of Dylan’s “Dear Landlord.” Can Joplin have been unaware that the song was rumored to be about Grossman? At the very end of 1969 she met and chatted with Dylan after a Kozmic Blues Band show at Madison Square Garden.

* None of which stopped Grossman claiming his $200,000 “accidental death” payout, though the San Francisco Associated Indemnity Corporation argued that Joplin’s death was a suicide, and he had to settle in the end for $112,000. In the civil trial he claimed, very disingenuously, that he had been unaware of the extent of her drug problems.