ON A STARRY summer night in early June 1996 I am dining with the Vermont jam band Phish and their very British producer Steve Lillywhite. The group is recording its seventh album in the nearby Turtle Creek Barn, converted into a second studio in the seventies by Albert Grossman, but they’re breaking for dinner in a pretty stone cottage built in 1917 for painter Caroline Speare Rohland.

For many years the house was known as Goodbrooks, but these days it’s more commonly referred to as “the Robertson house.” For this is where Grossman installed Robbie Robertson after the Band’s second album cemented their status as one of rock’s most revered acts.

A year later I’m at Turtle Creek itself, watching Australian singer-songwriter Richard Davies at work on his album Telegraph. Among its fine songs is “Crystal Clear,” written as the forests spectacularly changed color during his first fall in the Catskills. A photograph of Muddy Waters with Robertson’s former bandmate Levon Helm hangs on one of the studio’s walls, snapped on an icy day in February 1975 when the two men were recording here.

These convivial memories trump my recall of the main Bearsville studio just up the road. The first time I found my way there in 1991, I was asked to leave in no uncertain terms by a surly employee. The last time was twenty-two years later, after the shabby wooden structure had been bought by an eccentric hoarder from New York. In the company of John Simon, I drove up to see what was left of the place after Sally Grossman sold it in 2004. To our mutual horror we discovered that it had become a kind of trailer-trash dump.

Grossman had first thought about a studio when Dylan and the Hawks were using a portable reel-to-reel recorder in the basement of Big Pink in 1967. In a long interview two years later, Dylan himself told Rolling Stone’s Jann Wenner that “everyone’s talking about that now,” though he added that “some place like up in the country there, in the mountains, you could get a studio in, but that doesn’t guarantee you anything else but the studio.”

Indeed, Grossman was nearly beaten to the punch by Michael Lang. “A couple of years before Bearsville was built, I had come up with this idea of building a studio,” Lang says. “I don’t think Albert and I interacted over that, but I’m sure it gave him the idea.” Scouting around the town, Lang found an old Victorian house with outbuildings up on Yerry Hill Road. Until recently it had been a small hotel run by an Armenian family. “There was a big barn, a big studio building, as well as the main house where Alexander Tapooz lived,” Lang says. “It was on thirty acres, and it was just an ideal defunct run-down property. So we made a deal to take an option on it.” Pitching the concept to his Woodstock Ventures partners John Roberts and Joel Rosenman, he was met with skepticism: they didn’t believe there were enough rock stars in the town to justify the investment. By the time Lang’s and Artie Kornfeld’s “Aquarian Exposition” had got the attention of Roberts and Rosenman, the Tapooz studio was on the back burner.

As the Woodstock Festival plans got under way, Grossman seized his moment. Spending more and more time upstate, he sounded out his most trusted confidants on the subject of a studio. “Since John Court had gone, I was Albert’s sort of A&R person who knew something about that side of the world,” says John Simon. “He asked me what kind of studio he should build, and I told him my favorite one was the studio I broke in on, which was A&R’s Studio A on Seventh Avenue.” Simon obtained the dimensions, and Grossman “went and tripled them.” It was, Simon says, “typical Albert: ‘I’ll make one that’s three times as big.’ . . . As a result it never got used for years.”

Perhaps because he hadn’t been to one, Grossman liked to surround himself with bright young graduates of Ivy League universities. Simon had been to Princeton, as had Jonathan Taplin. “Albert loved these button-down guys as much as he loved hippie kids like me,” says Paul Fishkin. “If you had a suit and tie like Taplin, he was a real sucker for that. He was always calling and saying, ‘Hey, I’ve got this guy I just met that you might like. He came from Princeton; he has an MBA.’” It was through Taplin that yet another Princeton graduate was approached to design the Bearsville studio. John Storyk was an architect who’d been in the right place at the right time when, in April 1969, Jimi Hendrix and Mike Jeffery—along with recording engineers Jim Marron and Eddie Kramer—commissioned him to design the new Electric Lady studio in Greenwich Village. Taplin got wind of the Hendrix project and invited Storyk up to Bearsville to meet his boss. “Albert hired me on a napkin,” Storyk tells me in his office in Highland, an hour south of Woodstock. “He doodled out the site at the top of Speare Road.”

Storyk swiftly became one of Grossman’s indispensables: before long he had moved to Woodstock and would spend much of the next decade working for him. He was another of the rustic potentate’s surrogate sons, coming to love him as a paternal mentor. “Albert saw life through an extraordinary lens,” he says. “He was not particularly well-versed school-wise, but he had tremendous street smarts and was a pretty good judge of character—scrupulously honest, relentlessly tough in business.” Storyk says he “learned a lot about patronage” from Grossman: “You need a crazy person with an extra dollar or two. And when I had one or two down moments he was always there with some nice advice.”

Storyk doesn’t think Grossman saw the Bearsville studio as a properly money-making enterprise. “The original intent was just to be an in-house recording studio,” he has said—meaning a facility for Grossman’s own artists. Levon Helm certainly seemed to believe the studio would function as a kind of clubhouse for the Band when they first started using it. “They kind of parked themselves there for a while,” Storyk says. “It was definitely conceived as a place where a group could park and make it feel like a rehearsal studio. It wasn’t funky, but it was rustic.”

“When Albert really started to live up here in Bearsville more, his focus became more into developing a recording situation,” Bearsville staffer Vinnie Fusco told Billboard in 1980. “After The Band did Big Pink, the feasibility of recording in the country became more realistic.” Though Grossman was secretly more interested in his vegetable garden, he couldn’t just walk away from the music industry. This was the start of rock’s boom years; there was serious money to be made. Observing the tipping point was Paula Batson, who moved up to Woodstock in 1971 after working in New York for Johanan Vigoda. “The advances got crazy,” she says. “I remember Johanan doing international deals for Richie Havens that would have been impossible earlier. And that had an effect on Woodstock because people were now looking to cash in.”

Along with the studio itself came an offer from recording-equipment manufacturers Ampex for Grossman to start his own label. “The accountants moved up,” said Vinnie Fusco, “and the focus of the company began to move toward the record business.” With its cartoon logo of a bear’s head designed by Milton Glaser, the Bearsville label was one of a number of production deals that Ampex president Larry Harris struck in 1969. “They made two or three of them,” says Paul Fishkin. “They did one with Gabriel Mekler’s Lizard label and another with Phil Walden’s Capricorn. They were all busy ripping off Ampex!”

“Bearsville was really Albert’s grand vision of what was going to be the second half of his career,” says Michael Friedman. “He wanted to create this whole community up there, and he had the money to do it.” It was, adds Paul Fishkin, “Albert’s baby and Albert’s creation. . . . He wanted to bring it all to Woodstock and create that whole musical community that he was the god of. He wanted his management success to translate into record success, and he wanted it to be an extension of the world he was in of Dylan and Butterfield—that amalgam of blues and folk, a hip, rural, anti-pop-star thing that would succeed on its own terms.”

John Holbrook, a Brit who joined the Bearsville staff as one of its chief engineers, believes Grossman “put the whole studio together with his Ampex deal,” adding that “Other People’s Money” was one of his employer’s mantras. Yet the studio was a long time in the making. When Jim Rooney took up Grossman’s offer of a job as his studio manager, he arrived expecting to find, well, a studio. “I’d come up to Woodstock two or three times that winter, but the road to the studio was never plowed so I never saw it,” Rooney says. “Robbie Robertson seemed to be involved in some way, but all he would say about it was, ‘Oh, it’s gonna be great!’ That was all I knew, so I was really flying blind.” When Rooney finally saw the site in May 1970, it was nothing but a cinderblock shell; for the entire summer, Bearsville Studios was a construction job. Even when it semi-officially opened in September, the teething problems were endless. “It had its unexpected challenges for Albert,” says Michael Friedman, who moved to Woodstock that same year. “To build a studio is a specialty of its own, and there was a very steep learning curve for that.”

Jim Rooney claims the inaugural recording session at Bearsville was John Hall’s demo version of “Dancing in the Moonlight,” produced by John Simon. “They needed to get the bugs out,” says JoHanna Hall. “So Albert said to Simon, ‘You can have a month of free studio time.’” The Halls stayed with the Simons before renting their own cabin, and soon they too had fallen in love with Woodstock. Another early session brought eclectic California blues man Taj Mahal to Bearsville with Columbia producer David Rubinson. “Ours were, as I recall, the very first real recordings made [there],” Rubinson wrote of the January 1971 sessions. “It was unbelieeeeevably cold—mid-January upstate N.Y.—and it snowed about two feet deep.”** When the Band finally got into Studio B to cut a version of Marvin Gaye’s “Baby, Don’t You Do It” (aka “Don’t Do It”), they couldn’t get the sound they wanted. “It was just horribly frustrating for a long, long time,” admits Michael Friedman. “Albert spent a fortune on that building, and it took a couple of years before it really started working.” Drummer Christopher Parker says the studio was “still very much under construction” when he first went there, adding that “everybody’s complaint was that the two I-beams connected the two studios, so you couldn’t use both at the same time.” For years the far bigger Studio A served simply as one of Grossman’s many storage spaces.

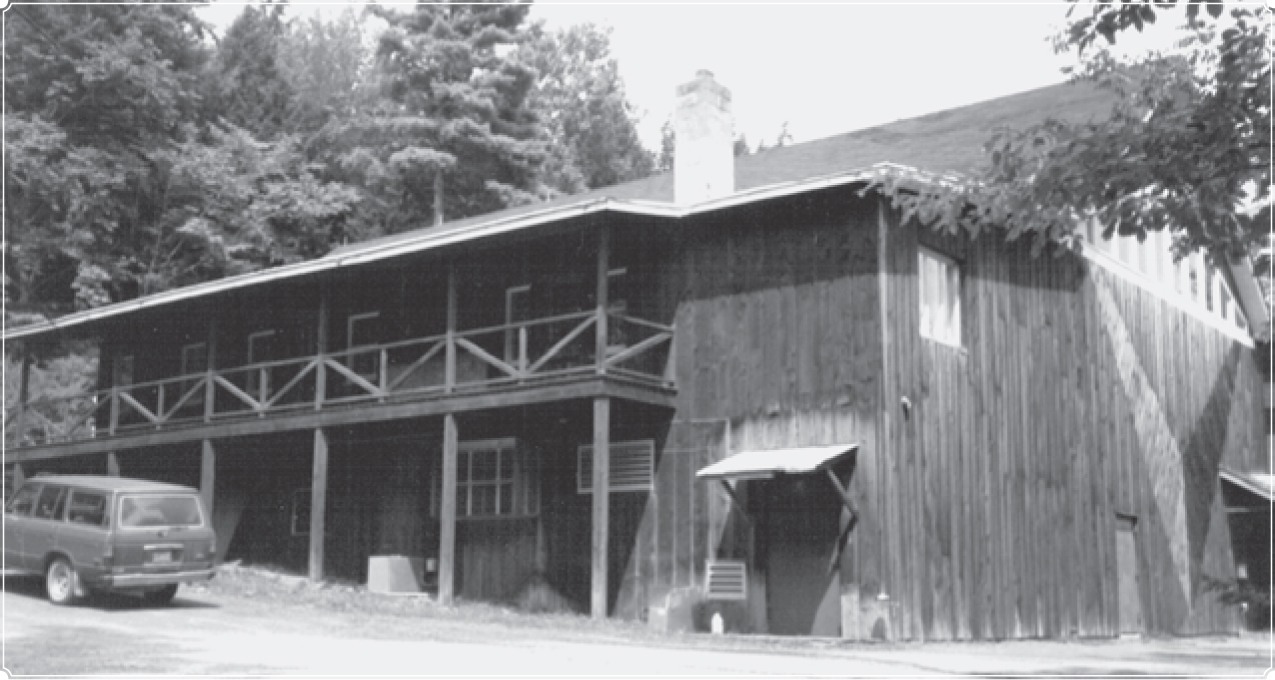

Bearsville studios, summer 1991 (Art Sperl)

As it turned out, the studio was only a part of Grossman’s grand scheme for establishing Bearsville/Woodstock as a music mecca. “The studio was just a business move,” says Jonathan Taplin. “The second phase, with the restaurant and then the theatre, I trace to having what I would call heartbreak. It was like, ‘Screw the business,’ and that’s when he began thinking about food and gardens and architecture.”

The heartbreak Taplin discerned stemmed from several traumatic events. Bruisingly, Bob Dylan had declared war on Grossman, a legal conflict that culminated in an agreement signed on July 17, 1970. “Albert told me he offered to flip Bob for a quarter of a million dollars,” says John Storyk. “I said, ‘Did he go for it?’ He said, ‘Nope.’ I said, ‘Would you really have done that?’ He said, ‘Absolutely.’” In the 1969 interview with Rolling Stone, Dylan had been circumspect about Grossman, telling Jann Wenner—on the subject of the aborted ABC-TV special—that “I think my manager could answer that a lot better” and even claiming Grossman was “a nice guy.” When Wenner pressed him later on whether he would continue to be managed by him, Dylan replied that if Grossman “doesn’t have a hand in producing my next concerts or have a hand in any of my next work, it’s only because he’s too busy.” By 1970, however, he hated his ex-manager so vehemently that he could no longer bring himself even to speak to him. When Grossman requested the return of the shtender on which Dylan had mounted his Bible at Hi Lo Ha, Dylan asked Bernard Paturel—who’d been hired to run Grossman’s new restaurant—to deliver it to him.

The next blow for Grossman was the arrest of Peter Yarrow in late August 1969 for “taking immoral and improper liberties” with a fourteen-year-old girl in a Manhattan hotel. Though he was later pardoned by Jimmy Carter, the damage to Yarrow’s reputation as a moral conscience of the folk movement was huge. Grossman remained loyal to one of his first stars, who recorded tracks for his first solo album at Bearsville, but it was another watershed moment that left him questioning whether his heart was still in management. And when Joplin died six months after Yarrow pleaded guilty, the spirit seemed to go out of him. “He spent more and more time in Woodstock, less and less time in New York,” says Jonathan Taplin. “He stopped being aggressive. It was more just like, ‘We’ll get it done.’ It was not as imaginative. He’d gotten hurt, that was clear.”

On top of these stresses, Grossman’s open marriage may have taken more of a toll on him than he ever admitted. “When I first went to work for Albert, he and Sally were living in the apartment on Gramercy Park,” says Michael Friedman. “She was around, and I found her to be really lovely. Then at some point she was just gone. Albert said she was living in Oaxaca in Mexico. I said, ‘Oh, are you breaking up?’ He said, ‘No.’ It was very matter-of-fact. He lived his life, and she lived her life.” John Storyk told Paul Smart that Grossman “had rough edges but was also a soft, pretty lonely guy in many ways,” while Odetta thought he was “a very private, very lonely and very alone person.”

Grossman channeled his passion into a vision of Bearsville as a kind of personal fiefdom. “He had the idea of providing a healthy environment for the artists to live in, with good healthy food,” says Peter Walker, another late-sixties import from Cambridge. “You take them out of the city, where they’re eating ratburgers, and you bring them up here, where there’s lots of fresh air. You feed them well in your restaurant, then you record them in your studio and have them showcase in your theatre, with the record-company executives flying in and staying in your cabins. That was the vision.” To Jon Gershen, Grossman’s plan was “to create something like a mini-Memphis or a Nashville, so that it became a center . . . and then you’d have this sort of brand.”

Among the musicians Grossman housed were the grieving members of the Full Tilt Boogie Band. “They were in a state of shock; they were paralyzed,” says Maria Muldaur. “They all knew Pearl was really good. And then it was like the world stopped. So Albert said, ‘Well, pack up your stuff and come to Woodstock.’ He was buying up all the land around Rick’s Road, which included several farmhouses. And he put the band up there.” Paul Fishkin claims Grossman “spent a fortune on Full Tilt. . . . He just let them rack up ridiculous amounts of studio time.” Yet little happened for the group in Bearsville. “We would have rehearsals trying to get songs together,” says Graham Blackburn, a temporary member, “but they would invariably devolve into much more intellectual jazz jam sessions than the rock and roll we should have been playing.” When the band finally collapsed, Blackburn says, “everybody split up in disgust.”

Grossman was more preoccupied by a fourteen-acre streamside farm at the bottom of Striebel Road that had recently come on the market. It included several barns and other outbuildings, as well as the nineteenth-century farmhouse itself. By December 1971 he had transformed two of the buildings into an upscale French restaurant. “These days a manager opening a restaurant is a normal thing, but at that time it seemed like a crazy and grandiose idea,” says Paula Batson, who worked there. “And to do it in Woodstock and make it fine cuisine? I mean, this was the pre-foodie era.” In Woodstock proper, the community looked on with mild amazement. “I thought, ‘Wow, Albert’s buying up the town,’” says Daoud Shaw. “For him it was like, ‘Why go to Deanie’s when I can have my own restaurant? I’m not that crazy about prime rib anyway.’”

Grossman took great pleasure in planning the Bearsville complex, recruiting the best local craftsmen to bring his dreams to fruition. He bought his lumber from Nelson Shultis’s sawmill and hired copper-roofing master Otto Shue. “He started searching around for things to buy,” says Dean Schambach. “We pulled those sheds together to form the Bear Café. Albert changed the town by building the Bear. The room with the fireplace had been a goat barn.” Along with Schambach and David Boyle, Grossman hired Paul Cypert, a local giant who quickly became his right-hand man. “Paul and I hit it off right away,” wrote Jim Rooney, who took over the books and payroll. “He was a master carpenter. He’d come to Albert’s attention while building a spiral staircase for John Simon.”

Rooney himself was soon co-opted into running errands for Grossman, driving down to the Port of Hoboken to collect imported chairs or picking up stoves and coolers from bankruptcy sales on the Bowery. “Albert was nuts to work for, because he was so obsessed with quality at a good price,” Rooney remembers. “He’d always say, ‘The other side of a bankruptcy is a bargain.’” Assisting him on some of the runs was Jon Gershen, who watched as Grossman drove Rooney crazy with his demands: “He had a way of interacting that he’d perfected and that worked to his advantage. The most memorable thing was the silence: Jim asking a question and getting nothing back. It was like seeing a psychoanalyst.” For Lucinda Hoyt, who worked as his “good fairy” in the Striebel house, Grossman had a “whammy” you could feel across a room. “It was like a hex, a mental projection that he emanated,” she says. “It put people off; it undid them.”

Paul Cypert, says Jon Gershen, was “a prince of a guy married up to this hippie baron of Woodstock.” He would often vent his exasperation to Gershen and Rooney. “He’d say, ‘How am I supposed to do that?’” says Gershen. “He was frustrated by all the juggling.” John Storyk was another who struggled with Grossman’s reluctance to see things through to completion. “One day I said, ‘Albert, why are we starting another project? Why don’t we just finish the theatre, and then we can start the next project after that?’” Storyk recalls. “And he turned to me and just said, ‘Why?’ Which was quintessential Albert. And at that point I got it. It wasn’t about finishing for him; it was about the journey.”

By the mid-seventies, Grossman had a ten-man construction crew working exclusively on his projects. Nor did he limit himself to Woodstock and Bearsville. “Just when you thought the last project was done, he’d say, ‘Hey, I got a house in Santa Fe,’” John Storyk says. “Or, ‘I have two acres in Puerto Escondido. . . . I wonder if you could take a look at it.’ It was always, ‘What does Albert have this week?’”

To Jonathan Taplin, Grossman was “really pulling back” from the music business at this point. “Bennett Glotzer did most of the booking and all the management stuff,” Taplin says. “I don’t think Albert was paying that much attention.” Besides, carpenters and chefs were easier to manage than musicians. To John Holbrook, Grossman “maintained an interest” in the studio but little more: “He liked to drop in and say, ‘Everything okay?’ But there was more concern about decoration for the restaurants. Like, ‘Do we have the right lights?’”

As “Albertsville” slowly took shape, even the doubters applauded the scale of Grossman’s ambition. “It was a brilliant idea to come to a place close to New York where he could do what he wanted to do,” says Robbie Dupree. “That’s why we called him the Baron. I don’t know how many houses he had, but I’m going to ballpark it as fifteen, sixteen properties in Bearsville. What he did was import the kind of people he needed, because they weren’t here. He understood that ‘If you build it, they will come.’” Grossman was no Midas, however. Not only was the studio having problems, the Bear wasn’t quite working either. “Albert brought this guy over from France, and he was not a great chef,” says Michael Friedman, now a restaurateur himself. “We used to have dinner there three or four nights a week for a long time—me and Taplin and the guys in the Band—and the guy never got it right. But the demographics couldn’t support that kind of place to begin with.” As Robbie Dupree points out, “the cops and the volunteer firemen who ate at Deanie’s weren’t eating $29 entrees at the Bear.”

“The World’s Foremost Rock Music Tsar,” Peter Moscoso-Gongora wrote in a scathing Harper’s magazine report on Woodstock, “has dinner a quarter of a mile from his studio, at his kitsch, brocaded ‘French’ restaurant called the Bear, with its atrocious food, its cupolas, its piped Bach chorales and its New York City prices. . . . Parvenu, like himself, it has been compared to a Bronx funeral parlor.” The plug was finally pulled on the Bear in 1972, when Grossman dreamt up the idea of the less recherché Bear Café.

To Paula Batson, the Woodstock scene was slowly being overshadowed by Grossman’s circle in Bearsville. “There were local bands, and my husband’s band Holy Moses was one that got a deal,” she says. “But by this time the Band and Albert and the other successful people were kind of sequestered off in their own group. Musically there was a kind of aristocracy.” A schism of sorts opened up between those in Grossman’s world—one Fred Goodman described in his seminal book The Mansion on the Hill as “a small, terminally hip and incestuous universe, with Albert as the sun”—and those outside it. “No one wants to admit it, but there was a hierarchy in Albert’s mind,” Mercury Rev’s Jonathan Donahue says. “It was almost like an Indian caste system. I mean, how would you feel if you were a local and all of a sudden Albert announces that he’s the new Rex in town, and here’s where the theatre’s going to be and here’s where the restaurants are going to be? Oh, and the laws are going to change a little bit too.”

“Albert was the lord of the manor,” says Maria Muldaur, who moved to Woodstock in the fall of 1970. “He could afford to have the best of everything, including a restaurant that was practically at the end of his driveway. And some of the wives of the guys in the Band and various other people aspired to his lifestyle. Robbie and Dominique were in that crowd. The girls wore long, flowing dresses, and there was a certain amount of putting on airs. If Albert had a certain kind of furniture, they wanted that furniture. If Albert proclaimed that a certain imported cheese was the absolute best you could get, they wanted that too.”

If many of Woodstock’s working musicians resented him, Grossman’s peers took a different line. “He gave Woodstock a new persona,” Michael Lang has said. “He took us out of our quaintness and really brought us national attention.” Happy Traum argues that “the whole Bearsville studio thing created a major vortex of high-end artists coming into town.” And to Milton Glaser, who’d brought him to Woodstock in the first place, Grossman “made [it] attractive for musicians. . . . [He] amplified a lot of what was already implicit in the town.”

In the end, not even Bob Dylan was immune to his ex-manager’s transformation of Bearsville. In the summer of 1971 he brought George Harrison in to see the studio Grossman had built. “I thought, ‘That’s interesting, what’s this about?’” says Jon Gershen, who witnessed the visit. “Bob appeared to be showing George around the studio. It was like he was saying, ‘Look what we have here in this town now.’”

It was certainly a very different place from the Woodstock that Harrison had visited three years before.

![]()

* Though the album was never released, three tracks from the sessions—songs recorded more successfully on the 1971 live album The Real Thing—emerged forty years later on The Hidden Treasures of Taj Mahal, 1969–1973.