THE BAND HAD good reason to call their third album Stage Fright. On the eve of their live debut in San Francisco, on April 17, 1969, Robbie Robertson came down with a mysterious illness that almost stopped the show, and even he wondered if fear wasn’t a contributing factor. Here the group was, having played no more than thirteen minutes onstage in four years, headlining for the first time with their own material—and with no Ronnie Hawkins or Bob Dylan to hide behind. Headlining, moreover, in front of a crowd of hippies in the capital of acid rock.

Many people, when they heard Stage Fright’s title song, assumed Robertson was writing about Bob Dylan. But “Stage Fright” spoke as much for the five men who’d shied away from the limelight in the Catskills as it did for the man who’d mellowed into the reclusive bard of Nashville Skyline. The scale of the Woodstock and Isle of Wight festivals unnerved them, while the success of The Band caught them by surprise, making them stars in their own right. On January 12, 1970, they were on the cover of Time magazine with the misleading headline “The New Sound of Country Rock.” “The Band appeals to an intelligent segment of this generation,” William Bender said in the opening “Letter from the Publisher.” “Many have tried the freaked-out life, found it wanting, and are now looking for something gentler and more profound.”

Little did Bender know what was really going on behind the scenes. After touring for the first three months of that year, the Band returned to Woodstock to prepare for their third album. This time the fraternal spirit was tougher to summon: though they were starting families, fame and money had disrupted the group’s tenuous chemistry, while drugs and alcohol were beginning to mess with the health of at least three of them. Libby Titus would later describe Richard Manuel as “the worst alcoholic I’ve ever met in my life,” claiming he drank “quarts of Grand Marnier” every day. “Richard was drinking too much from the very beginning, and his liver was now pushing up into his stomach,” says Jonathan Taplin. “Levon had some serious problems with downers. Rick was like a hoover; he’d take whatever was around. Garth would have a little toke once in a while, but he was very moderate. At that point Robbie was Mister Responsible.” Fans of the Band who idealized them as peaceful farm boys would have been shocked to learn that even opiates were not off-limits to them. “I hope we didn’t,” says Peter Coyote, “but I’m afraid Emmett Grogan and I might have been the people that introduced Levon to heroin.” Pictures Elliott Landy took of the Band outside Manuel’s and Hudson’s Spencer Road house appear to show Helm in an opiated state. “Heroin was a problem,” Robertson admitted. “I never liked it, never understood it, and I was scared to death of it. But it came through, you know, like everything else came through.”

“After the Time cover, things got a little crazy,” admitted Danko. “Luckily, the people in Woodstock looked after us. The local judges and the police called us ‘the Boys.’ And we felt that protection.” If police chief Bill Waterous referred to Woodstock’s hippies as “bums and freeloaders,” he let the Band get away with everything but murder. “Billy loved them,” says Richard Heppner. “And he loved them because they could cross over that redneck line very easily.” Today we’d say that Waterous was enabling the Band, as many other Woodstockers did. “They were out of control and utterly indulged,” admits Paul Fishkin. “It was all wrong, and it was responsible for so much of the destruction of lives and business entities.”

When Danko and Manuel showed up at the Concert for Bangladesh in New York, Bob Dylan gave instructions not to admit them backstage. “I was told, ‘Bob doesn’t want them here,’” says road manager Paul Mozian. “He didn’t want serious carousers affecting George and Ringo.”

IT WASN’T JUST the Band hell-raising around town. Joining them in their escapades was the hard-drinking Paul Butterfield. Another boozing buddy was Mason Hoffenberg, then on the methadone program in Kingston. Woodstock was in any case filling up with assorted leeches and drug dealers. “There started to be a lot more insidious drugs than pot going on,” says Maria Muldaur. “People were starting to snort coke, and a lot of alcohol was being consumed by virtually everyone: our band, Paul’s band, everybody.”

“This wonderful, nymphomaniac group of young rock stars became surrounded by these extremely charming and attractive vultures,” Libby Titus recalled. “John Brent, Howard Alk, John Court, Larry Hankin. Some of them were brilliant, charismatic junkies, like John Brent, who was so magnetic you wanted to be a junkie ten minutes after you met him and heard his stories of beautiful girls in the Village and shooting up with William Burroughs. And that’s what happened.” Titus herself would struggle with addiction for years, while Alk would die in 1982 of an overdose—a suicidal one, according to his wife, Jones—in Bob Dylan’s Santa Monica rehearsal studio.

For the abstemious Robertson, the antics of his compadres were disappointing and frustrating. “Robbie always had the highest goal in mind, whereas the others were happy just to be playing music,” says John Simon. “Robbie said, ‘When I get out to Hollywood, I’m gonna get involved with films. I’m gonna work with Ingmar Bergman.’ That’s the kind of guy he was.” Others thought the guitarist pompous and standoffish. “He was the quintessence of super cool and super hip,” says Paul Fishkin. “I hated the pretension of all that shit. There was this whole atmosphere of Hipper-Than-Thou that pervaded Albert’s and Robbie’s world.” Like Fishkin, Michael Friedman was unimpressed by the airs Robertson and others put on. “Everybody kind of sounded a bit the same, except for Levon, Rick, and Richard,” he says. “There was this kind of whispering wisdom, the way Robbie spoke and the way Jonathan Taplin spoke. They all got into this kind of Band-speak, and at a certain point it was like, ‘Come on, guys!’”

The eccentric Hudson, meanwhile, kept to himself, moving into a house in the tiny hamlet of Glenford. “Just having a guy who could walk down the hill and sit at your piano and play Bix Beiderbecke’s ‘In a Mist,’ that didn’t hurt,” says Geoff Muldaur. “Of course he’s a strange cat, but he couldn’t be any sweeter.” Musical genius that he was, Hudson was also something of a mountain man. One night after Helm hit a deer, Garth skinned the dead animal with a penknife in the car’s headlights.

Once the Band accepted that their manager’s studio wasn’t going to be ready to use, the concept for Stage Fright became a live album to be recorded before an invited audience at the Woodstock Playhouse. “I thought, ‘Let’s have a little bit of a goof here,’” Robertson remembered. “It was, ‘Let’s do some touching things, some funny things. Let’s do more of just a good-time kind of record.’”

It didn’t take long for town officials to veto the idea of a live album. And by the time the Band had resigned themselves to using the theatre as another ad hoc recording studio, the music taking shape was anything but good-time. “I found myself writing songs I couldn’t help but write,” said Robertson, who up to this point had eschewed confessional writing. Along with the title track, songs like “The Shape I’m In,” “The Rumor,” and “Just Another Whistle Stop” did more than hint at the unrest behind the scenes. Even “Sleeping”—as wistfully lovely as it was—came a little too close to the truth about its cowriter, Richard Manuel.

True, the setup at the Playhouse was congenial enough when recording began in late May 1970. Patti Smith, an all-but-unknown poet who came by in early June with her boyfriend Bobby Neuwirth, found the atmosphere friendly. In a Band profile written for Circus, she anticipated an album that was “pretty positive, looking at things with a friendly, ironic eye.” She also bonded with Todd Rundgren, the hotshot young engineer on the session. One result of having him on board was that Stage Fright was more polished than its beloved predecessor. This time around, the Band sounded like an actual rock group, with each instrument clearly defined in the mix. Particularly prominent was Robertson’s guitar, treated with effects and devices that pushed it into the foreground.** Also noticeable on Stage Fright was the relative lack of harmony singing. This time, more of the songs were recorded with solo vocals, making the voices sound distant from each other. Only on “The Rumor,” a troubling statement about a stiflingly incestuous community, did they really come together, weaving lines in the rough-hewn gospel style they’d mastered on their previous records. “That song was about Woodstock,” John Simon says. “I had a line in one of my own songs that went, ‘Rumors fly around this town / Like echoes around a canyon.’”

Not that there wasn’t marvelous singing on the record: Helm sounded like a redneck Lee Dorsey on the boisterous “Strawberry Wine,” and Manuel was at his most droopily soulful on “Sleeping.” On “Stage Fright” Danko sounded genuinely spooked. Instrumentally, Garth Hudson was magnificent throughout: playfully fluttering on the accordion on “Strawberry Wine,” dreamily evoking childhood on “All La Glory.” Danko’s fretless bass anchored the songs in a deep throb, Helm’s drumming was organic and intuitive, and Robertson’s needling Telecaster incisions on “Sleeping” and “The Rumor” were spine-tingling. But one could argue that the blithe “Time to Kill”—“We’ve got time to kill, Catskill, sweet by and by”—masked a certain ennui. One question suggested itself: Why was Manuel contributing less and less as each Band album rolled around? “I did everything to get him to write,” Robertson claimed. “There’s no answer. My theory is that some people have one song in them, some have five, some have a hundred.” To John Simon, there was no question of Manuel being squeezed out: “Robbie certainly didn’t consciously intimidate him, but then when you met Robbie, he was so smooth and urbane and witty, whereas Richard was such a gee-golly-gosh kind of guy.”

Received more coolly than The Band, Stage Fright still reached the top 5 in the Billboard album chart after its release in September 1970—the highest-charting album of their career. The group spent three months touring America, flying to northeastern dates in a little turboprop airplane. “Some of the shows were real good,” said Robertson. “Sometimes it got real accurate and sometimes we were just crazy rock and roll musicians. But when it was really good, when we all played well, it made us feel just tremendous.” After wrapping the tour in Miami that December, the five men went into winter hibernation.

By the time they poked their noses out of the New Year snow, the Bearsville studio was ready for them to start work on their next album. “In my mind I had my own key to the studio and had drums set up everywhere that I never had to take down,” Levon Helm later told me. “I had this wonderful world built up in my head where the Band would just be making music all the time, and it would just be hand over fist with money and albums, and who’s got time to count it?”

What Helm hadn’t reckoned on was Robertson hitting a nasty patch of writer’s block and Richard Manuel drying up completely. “It was frustrating, a horrible feeling,” Robertson remembered. “I just didn’t have the spirit to write. A lot of the songs were half-finished ideas.” More than ever, he was struggling to hold the Band together. “He became the leader because nobody else wanted to be,” said Bill Graham. “Levon had been the leader, but he wasn’t enough of a decision maker.”

Given all this, it’s a wonder there was any decent music on their fourth album, Cahoots. “Life Is a Carnival” remains the funkiest track the Band ever recorded. Bob Dylan’s “When I Paint My Masterpiece” was a droll fusion of chanson and Arkansas hoedown, and Helm’s singing on “The River Hymn”—with Libby Titus harmonizing behind him—was exquisite. Manuel’s boozy sparring with Van Morrison on “4% Pantomime” was a soulful hoot. “Richard brought a real understanding of Ray Charles to the whole thing,” Artie Traum said. “I don’t think he ever knew how good he was. He was very self-effacing and very modest.”

Huge fans of New Orleans legend Allen Toussaint’s R&B and soul productions, the Band couldn’t believe their luck when he agreed to write the extraordinary antiphonal horn charts for “Life Is a Carnival,” a song based on a sprung funk groove Helm and Danko had worked up at Bearsville. “When I heard that song . . . the intro was really strange,” Toussaint said in 2011. “The way Levon plays is sort of upside down and sideways sometimes. When I first heard it, it was like turning on the radio in the middle of something and you don’t know exactly where the ‘one’ is.” For Toussaint, the Band’s music was “another kind of genre that I couldn’t put in a certain file cabinet.” He was astonished by Garth Hudson, who would “tinker with things to get tiny different sounds and work ever so long to get a slightly different sound. . . . You’d wonder was it worth it but when you heard the final things [you’d think], ‘Oh yes, that’s the difference in him and all the other players in the world.’”

For all the infectious propulsion of “Life Is a Carnival,” Cahoots was an album of lamentation, mourning the passing of American traditions. Loss permeated “Last of the Blacksmiths” and “Where Do We Go from Here?” “The record poses the question, ‘What are things coming to?’” said Robertson. “It dealt with the fact that things like carnivals and blacksmiths were vanishing from the American scene.”** Jim Rooney, who witnessed the Cahoots sessions at Bearsville, felt that some of the group’s creative energy was slipping away. “One day when I came in, Robbie was in the control room and Levon was out in the drum booth banging away,” he wrote. “For what seemed like an eternity Robbie and [engineer] Mark Harman were laboring with the EQ knobs and various gadgets to get what they referred to as a ‘drum sound.’ It seemed simple enough to me. Put some mics on Levon’s drum kit and let him play. As I watched them on that day and over the course of the next weeks, it became clear that the other band members were basically letting Robbie run the show.”

Released to muted reviews in the fall of 1971, Cahoots never made it higher than number 21 and spent just five weeks in the top 40. Some wondered if Robertson’s elegies for the blacksmith and the eagle weren’t sublimations of his feelings about the Band. “Everybody had been so easily satisfied before,” he said in 1982, “and then it got harder to do what we did at ease. The inspirational factor had been dampened, tampered with, and the curiosity wasn’t as strong.” One of the dampening factors was the ill feeling between him and Helm, who had begun to realize that the guitarist was making significantly more money from the group’s songs than he was. “Every band is a community effort,” says Jim Rooney. “But then suddenly it isn’t a community effort if you don’t have a piece of paper to say it is. Levon found that out a little too late and was certainly very bitter about it.”

“My opinion on this is very clear,” Jonathan Taplin states. “Robbie wrote the songs. He got up every morning and worked on writing. I saw it. And it wasn’t because he wanted to hog it; it was because nobody else was doing it. It’s true that at that time nobody understood how, years later, publishing income would be the only income you could really count on. But then the others were all around Dylan, and they must have known how much money he was making from publishing. There was no need for this myth that they all got screwed by Robbie. It’s the same as saying Bob got screwed by Albert.” Sally Grossman would be the first to agree. “There’s this alignment that goes on that Albert and Robbie ripped Levon off,” she said in 2014. “I don’t know, maybe it could have been done better, however they had signed their deal. But I mean, there’d be these band meetings and the only one that would show up was Robbie. While Rick was going off the road and breaking his neck, Robbie was focused. Albert and Robbie set off to rip Levon off? Oh please.”

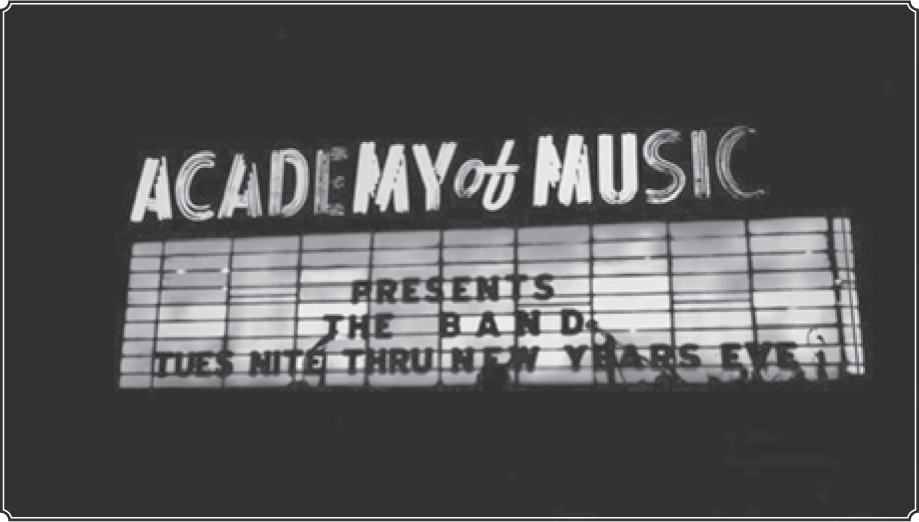

Fortunately the Band overcame their inner tensions for long enough to record one of rock’s finest live albums. “The only rock record I owned was Rock of Ages, and the reason I bought it was because I saw the horn players on it,” says jazz trumpeter Steve Bernstein. “I think they’re the greatest horn parts ever in rock and roll.” The double album, recorded at the very end of 1971 at New York’s Academy of Music, was the culmination of the many great shows the Band had played that year—including two at the hallowed London venue where they’d been booed with Bob Dylan. “I remember they came out onstage at the Albert Hall, and they were all wearing suits,” says Keith Reid of the gig he saw. “And the way they had their setup was so unusual, with the drums to the right and Garth in the middle. They’d play a couple of numbers and then all switch instruments. Levon got off the drums and picked up a mandolin, and Richard got on the drums. And it still sounded fantastic.”

For the four Academy of Music shows, the group attempted something new and bold. After the syncopated thrill of the arrangements on “Life Is a Carnival,” they invited Allen Toussaint up to a wintry Bearsville to write horn parts for a number of older songs. “There were no houses around, just trees,” he said in 2011. “It was so beautiful out there and I thought, ‘It would sure be nice if it was snowing.’ The next night it snowed and I put on a pair of pajamas and kept going. It was one of the best times in my life.” Toussaint’s arrangements—played by a crack New York horn section—transformed songs such as “Rag Mama Rag,” “Unfaithful Servant,” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” “Don’t Do It” was stupendously funky. “Across the Great Divide” and “The W.S. Walcott Medicine Show” swung like big-band jazz. On New Year’s Eve, during the countdown to midnight, Garth Hudson turned the introduction to “Chest Fever” into an extended keyboard fantasy that was equal parts Anglican hymns, Scottish reels, Charles Ives, and Thelonious Monk. For the encore, the group was then joined by none other than Dylan, who launched into a rambunctious version of the basement song “Crash on the Levee (Down in the Flood),” followed by “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” “Don’t Ya Tell Henry,” and “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Exhilarating though the Academy shows were, the comedown felt grim. Where could they go from there?

![]()

* The mix had its own curious history: Robertson wanted Rundgren to mix the album, but Helm argued for sending the tapes to British engineer and producer Glyn Johns. Rundgren flew to London with the tapes and started his own mix at Trident studios, while Johns worked simultaneously at Olympic. “It turned into a game,” Johns recalled. “It was like a competition, which I thought was howlfully amusing.”

* Woodstock’s own last blacksmith was Henry Peper, born in 1859. His shop on Mill Hill Road became Peper’s Garage.