IN JAMES LASDUN’S story “Oh, Death,” a white-collar professional moves into a house on a mountain road in upstate New York and commences a tentative friendship with neighbor Rick Peebles. Rick has lived in the next-door house since birth and resents the second-home owners who’ve bought up parcels of land that used to be his boyhood haunts. He is a kind of Northern redneck: frustrated, Harley-riding, occasionally gun-toting. When he marries the unhappy Faye and takes in her two children, they celebrate their nuptials with a hog roast and music by a local bluegrass band: “Two fiddles, a guitar, a banjo and a mandolin, the players belting out raucous harmonies as they flailed away at their instruments.”

The story’s unnamed narrator tells us he is already a fan of this music, that he listens to Clinch Mountain Boys CDs on his daily commute to work. It’s a sound, he says, that seems “conjured directly out of the bristly, unyielding landscape itself . . . arising straight out of these thickly wooded crags and gloomy gullies.” Howling along with Ralph Stanley in his car, it’s as if “a second self, full of fiery, passionate vitality, were at the point of awakening inside me.” He could be speaking for all urban lovers of vintage Americana music.

A year after Rick and Faye’s wedding, Lasdun’s narrator unexpectedly runs into them at a party hosted by Arshin and Leanne, members of the local “healing community.” Lasdun doesn’t identify the place as Woodstock, but it may as well be, since “Oh, Death” beautifully illustrates the tension between the town’s rural populace and the yoga-loving imports living out fantasies of getting away from it all. In due course, Rick’s life itself becomes something like a Ralph Stanley song—an Appalachian tragedy in the Catskills.

On a warm fall Saturday at his house in Shady, I sit with Lasdun over lunch and talk about the place he’s based himself in for over two decades. “A lot of American towns are either just so entrenched in their own rural matters or they’re too self-conscious,” he says. “Woodstock is one of the very few places that has this combination of being real country and laid-back but where you can also take for granted that everybody’s politically aligned.”

He seems surprised, however, when I quote to him Richard Heppner’s statistic that the percentage of second-homeowners in Woodstock has grown to almost 70 percent. He concedes there is class tension in the area, citing the Confederate flags that used to appear on students’ cars at his daughter’s high school in Onteora. He also remembers a spate of barn burnings around town in the late nineties that had people “baying for blood”—till it transpired that the arsonist belonged to Woodstock’s well-entrenched Shultis family. “All of a sudden it quietened down, and the guy got an electric bracelet for a couple of weeks. When he was asked for his motive, he said something like he was fed up with not being able to get a cup of coffee for under two dollars.”**

SURROUNDED BY THE very blue-collar people whose lives their music is about, middle-class folkies and bluegrass singers had made Woodstock their home since the early sixties. After Music from Big Pink fixed it in popular consciousness as a musical enclave, dozens of primarily acoustic—and often university-educated—players and songwriters began to settle in and around the town. “Happy Traum and John Herald lived there, and Artie Traum had just come up,” says Jim Rooney, who moved into his Lake Hill house in late 1970. “By the time I arrived, it was quite a community.”

Within a few months, banjo player Bill Keith—who’d played with Rooney in the early-sixties bluegrass duo Keith & Rooney—had joined them. So had Geoff and Maria Muldaur, who’d played with Keith in the Jim Kweskin Jug Band. “We were all still in Boston, so I said, ‘Let’s get down to Woodstock,’” says Geoff. “We looked at a very nice house on Glasco Turnpike, but it wasn’t quite right for us. So I told Bill about it, and he went and got it. He still lives in that house today.”

Keith is a regular at the weekly Bluegrass Clubhouse night held at Woodstock’s Harmony Café, run by Sha Wu, the chef Albert Grossman brought up to Bearsville in 1978 to run a Chinese restaurant called the Little Bear. (A signed photograph of Grossman still hangs behind the Harmony Café’s till.) The Clubhouse is sparsely attended at the best of times, even when Keith sits in and picks along with singer-guitarist Brian Hollander, singer-mandolinist Tim Kapeluck, and Stetson-wearing pedal-steel player “Fooch” Fischetti. Running through a repertoire of country classics—Patsy Cline’s “Walkin’ after Midnight,” Lefty Frizzell’s “Long Black Veil”—and close-harmony bluegrass beauties like the Louvin Brothers’ “How’s the World Treating You,” the ad hoc group is heartily applauded by the handful of aficionados who’ve ventured out on this chilly October night. But it’s a pale echo of the live roots-music scene that thrived in Woodstock’s bars and clubs in the early seventies.

“There were four or five clubs in this one little town,” says artist manager Mark McKenna. “In one place there’d be Paul Butterfield and in another Tim Hardin, in another Maria Muldaur. And all those people had a kind of fraternal sense and would play together and write together.” Bill Keith, for one, must look back on those times and wonder what happened—especially when you consider that he revolutionized five-string banjo picking in the nine remarkable months he played with Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys in 1963.

Shortly before moving to Woodstock, Keith played pedal-steel guitar on 1970’s Pottery Pie, the first album by Geoff and Maria Muldaur after their split from Jim Kweskin. Also playing on that earthy, easy-rolling record—produced in Boston by Joe Boyd—was Amos Garrett, a guitarist then coming to the end of a two-year stint in Ian & Sylvia’s Great Speckled Bird. Keith himself had also done time in the Bird, unsung pioneers of country rock. Still managed by Albert Grossman, Ian and Sylvia Tyson had reached a point of stagnation with their dated folk sound. They’d already recorded the countrified Nashville and Full Circle albums when—under the influence of the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers—they started again from scratch. Already a local legend on Toronto’s Yorkville folk scene, Garrett was the first musician they approached.

Almost overnight, Great Speckled Bird became a bona fide band of electric rockers. Having alienated their old folk fan base, they were passed over to John Court, who put them in a Nashville studio with the long-haired, satin-pants-wearing Todd Rundgren. “It was a peculiar marriage, God knows,” Sylvia Tyson recalled. “You have to understand that we were doing that at Jack Clement’s studio, right in the heart of Nashville, with all of the old boys that we’d played with dropping by.”

The third release on Grossman’s new label, Great Speckled Bird was equal parts Canadian country and hippie Bakersfield, shot through with the Tysons’ folk harmonies. Playing off Buddy Cage’s steel lines, Garrett excelled on the funky, full-throttle opener “Love What You’re Doing, Child” and the wistful waltz-time ballad “This Dream,” sounding at moments like a fusion of James Burton, Clarence White, and Curtis Mayfield. “I don’t know anybody that plays like Amos,” says Jim Colegrove, Great Speckled Bird’s second bassist. Garrett was still in the band when they joined the Festival Express tour in that summer of 1970. “We were the darlings of that tour,” drummer N. D. Smart II remembered. “We were the ones that everybody stood on the sidelines and watched.”

By September, Garrett was living in Woodstock, with Smart and Colegrove following close behind. “After the Pottery Pie sessions I sent Amos a package,” says Geoff Muldaur. “It had this thing rubber-stamped all over it that said ‘Leave Ian and Sylvia today!’ And he did!” The first person Garrett encountered after moving into a cabin off the Wittenberg Road was John Herald, who, Garrett recalled, “came crashing out of the woods and shouted ‘Hi!’” Smart and Colegrove drove up soon afterwards, searching for a guitarist to replace Garrett in Great Speckled Bird. “While we were there we thought, ‘Well, this is a nice place, and there’s a lot going on up here,’” Colegrove says. “We knew Albert was building a studio, so we thought, ‘Maybe we should look for a place up here and get in on the ground floor of whatever’s gonna happen at Bearsville.’”

“There was a whole folk contingent that came in,” remembers Happy Traum. “Jim Rooney, Bill Keith, Geoff and Maria, Amos, N.D. And Johnnie Herald was already here with his bluegrass thing. So it was a very strong scene.” Others who followed in their wake were John Sebastian and singer-songwriters Paul Siebel, Eric Kaz, and Roger Tillison, the latter lured to Woodstock by Levon Helm (who fell out with him before Atco released Roger Tillison’s Album in 1971).** For some, there was a clear line demarcating this folk crowd from the town’s electric rock and blues musicians, though in reality there was plenty of overlap between the two camps. “You were either a musician, or there were all these folk people,” says Graham Blackburn, with a sniff of disdain. “Maria Muldaur had a little more spunk, and Geoff was kind of cool. But I’ve always liked stuff that struts, that’s up there. And that was what I responded to in Van and Butterfield.”

With money from the Reprise deal that Grossman had negotiated for them, the Muldaurs paid $31,500 for a house on two acres off Boyce Road in Glenford, where they had an illustrious neighbor. “Every morning we’d hear Garth Hudson practicing Bach on the organ,” says Maria. “It would just come wafting across the treetops into our bedroom.” The Muldaurs already knew Bob Dylan and had met Janis Joplin when Big Brother supported the Kweskin Jug Band in San Francisco. (They’d barely settled into their new home—dubbed “Hard Acres”—when Bobby Neuwirth called with the shattering news that Joplin was dead.) “You had this amazing community of our band, Butterfield’s band, and the Band,” Maria says. “And meanwhile people like Johnnie Herald and Billy Faier were still active. Talk about the hills being alive with the sound of music. It wasn’t the normal kind of rock-star lifestyle. We were happy hiding out in the woods and doing all that kind of earthy stuff, as opposed to hobnobbing around Hollywood. Our music was developing organically, like our gardens.”

Keen to grow their own vegetables at Hard Acres, the Muldaurs sought the advice of Levon Helm. “He stood there with baby Amy in his arms and talked about fescue,” Maria says. “It was touching to me that he knew the merits of one kind of ground crop over another.” While they grew tomatoes and waited for gigs to roll in, the Muldaurs set to work on their second Warners album at Bearsville. Sweet Potatoes was a quintessential Woodstock recording of the period: rootsy, sexy, an eclectic mix of sultry blues and retro jazz. The Muldaurs were both great singers, and the backing from Amos Garrett, Bill Keith, Paul Butterfield, and others was sublime.

The Muldaurs’ sophomore offering, recorded at Bearsville in 1972 (painting by Eric Von Schmidt)

“I took to hanging out with Amos and Paul,” Geoff says. “I would also hang out with Albert, of course—that was a second home up the hill—and eventually with Danko, who was crazy enough to stay out all night with us.” Drinking and drugging were endemic in the Butterfield circle, and Muldaur soon succumbed to the temptations on offer. “In my last Woodstock house on Ratterman Road,” says John Simon, “there was a memorable pool game between Butterfield and Muldaur. Butterfield, with his typical braggadocio, said, ‘I’m the best Chicago pool player ever!’ Muldaur countered with, ‘I’m the best pool player!’ They got a gallon of cocaine and were still playing when I woke up at seven in the morning. Butterfield went to Albert next day and said, ‘I need five grand to pay Geoffrey.’ Albert just said, ‘Nope.’”

Hard Acres was itself something of a party house. On New Year’s Day 1971, the Muldaurs hosted a bash to which most members of Grossman’s circle were invited. Lubricated by Geoff’s bourbon-and-ice-cream punch, the menfolk watched football on TV, while the women labored in Maria’s kitchen making black-eyed peas with cornbread. (“This was all sort of pre–women’s lib,” she says.) Accompanying Grossman to the party were his houseguests Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett. When Eric Von Schmidt broke into a bastardized version of the white gospel standard “Will the Circle Be Unbroken”—mischievously retitling it “Will the Serpent Be Outspoken”—the Bramletts took Southern umbrage. “It offended their Baptist sensibility,” Maria recalls. “They demanded that Albert take them home.”**

THERE WERE PARALLELS between Woodstock and L.A.’s Laurel Canyon, where sixties bands broke up to produce seventies solo performers who hung out—and sometimes slept—with each other. “Dylan’s song ‘On a Night Like This’ was a great little vignette of a winter-night tryst in Woodstock,” says Maria Muldaur. “There was a lot of sneaking around through the woods and ending up in somebody else’s cabin—a lot of cross-pollinations going on besides the music. And, dear God, it was fun before all the hideous diseases could wipe you out for having a night like that.” In 1977, Amos Garrett said he couldn’t “remember anyone with a steady old lady or wife [in Woodstock] that didn’t split up or divorce within a few years of being there.”

One of the more damaging trysts was that between Maria Muldaur’s husband and Jim Rooney’s wife. “I would see Geoff coming in the back door of the Squash Blossom, where Sheila Moony Rooney worked,” says Stan Beinstein. One afternoon, Jim Rooney came home to find Geoff mowing his lawn, and “a tiny lightbulb” went on in his head. Soon Sheila had moved out of their Lake Hill home and into a carriage house on John Court’s property in Palenville. When Geoff later covered Bobby Charles’s “Small Town Talk,” Maria hated “the way he sang it so innocently.” “Geoffrey bought a Chevy Blazer and drove out of our driveway in a blaze of glory,” she says, confessing that she went in tears to Grossman to ask for a waitressing job at the Bear. “I’d been waiting hand and foot on Geoffrey for years, so I figured I must have some skills in that department,” she says with a snort of laughter. “Albert looked kind of sad, but I could tell he didn’t have the fatherly instinct.”

Maria laid low in Glenford, where her neighbor lent much-appreciated support. “Garth was so dear,” she says. “He would come down the hill and say, ‘Well, I’m getting my snowplow out today—you want me to plow you out?’ He was a darling man.” In the summer she drove to secret swimming holes with John Herald and Artie Traum. “I still make a pilgrimage to Palenville every year,” she says. “The water that comes down from the Catskills is so pristine you can drink it.”

IN LATE SEPTEMBER 1971, Happy Traum received an unexpected call from an old friend. “Can you come into the city tomorrow with your guitar and banjo?” Bob Dylan asked. “Oh, and do you have a bass?” The next morning, Traum boarded a Trailways bus and made the trip into Manhattan. There was no one present at Columbia’s Studio B besides an engineer and Dylan himself, who had decided to flesh out his forthcoming Greatest Hits, Volume II with new versions of “I Shall Be Released,” “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” and “Down in the Flood” (together with “Only a Hobo,” a song he’d first recorded in 1963). The spirit of the session was quick and good-humored: even “I Shall Be Released” was reworked as a jaunty sing-along, while “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere”—with Traum wailing along and adding what he calls “a frailing banjo part”—was a blast of fraternal fun. “At the end of the session,” Traum says, “Bob told me he felt stimulated to prove himself again.”

Whatever the reasons Dylan had for revisiting these particular back pages, the recordings stimulated Traum as much as they did his old friend. Disenchanted with the music business after a less-than-stellar stint on Capitol Records, he and his brother Artie now hatched the notion of a loose revue of the folk and bluegrass musicians they knew around Woodstock. “We just decided to go in a different direction,” Traum says. “We said, ‘Let’s do the music we love to do when we’re sitting around at parties.’” In the recollection of Jim Rooney, “I was working at Bearsville, but this other community was all around me, and we would get together for what we called ‘picking parties’—Artie and Happy and Bill and me and Maria.”

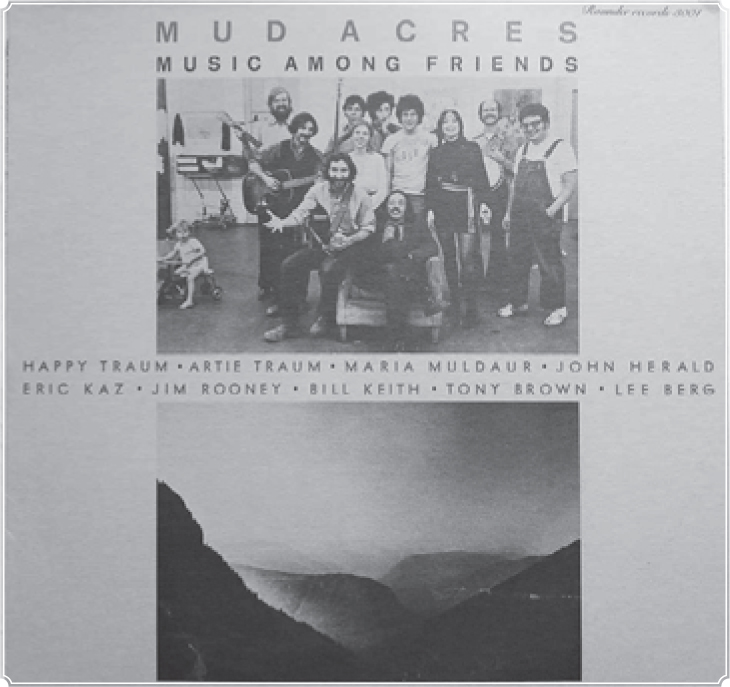

Rounding them all up in January 1972, the Traums booked a small four-track studio north of Saratoga Springs and “literally camped out on the floor” for a long winter weekend. From this extended song circle came the album Mud Acres: Music Among Friends, with the Traums accompanied by Maria Muldaur, Jim Rooney, John Herald, Bill Keith, Tony Brown, and others.** “I think Artie came up with the name,” says Rooney. “It referred to mud season in the country, when all the roads were dirt and everybody’s car would be covered with mud.” Covering or adapting ancient favorites by Gene Autry (“Cowpoke”), the Delmore Brothers (“Fifteen Miles to Birmingham”), and Blind Willie Johnson (Muldaur’s solo showcase “Oh, the Rain”), the Mud Acres ensemble was a kind of folkie Basement Tapes five years after Dylan’s Big Pink summer. “It was like, ‘Okay, Johnnie, you take the lead on this one. . . . Bill, you do this banjo instrumental,’” says Happy Traum, who described Mud Acres as “an album of songs that convey the sense of closeness, personally and musically, that we feel, as well as the fun of doing something for its own sake, as opposed to doing it for financial or other ends.”

The first Mud Acres album, released on Rounder in 1972

Over the ensuing years, the Mud Acres concept evolved into the Woodstock Mountains Revue, rooted in the core unit of the Traums, Herald, Keith, and Rooney but embracing other friends new and old. “It was like an aggregator,” says Stan Beinstein. “Some of the greatest folk music of the seventies is on the first two Rounder albums by the Mountains Revue.”

“The second album was done at Bearsville in 1977,” says Happy Traum. “We sort of expanded our group to include Pat Alger, who’d moved here from the South and became a very successful songwriter. Eric Kaz and Maria Muldaur moved to California, but John Sebastian and Eric Andersen became part of it, as did Rory Block, Gordon Titcomb, and Rolly Salley, who wrote ‘Killin’ the Blues.’ Paul Butterfield joined in, and he and Sebastian did this fabulous harmonica duet on ‘Amazing Grace.’”

Further albums followed, with Larry Campbell and Cindy Cashdollar augmenting the moveable feast. “The first day I got up here, John Herald introduced me to Happy and Artie,” Campbell remembers. “He was doing a rehearsal with the Revue, so I met Bill Keith and Jim Rooney and all those guys. It felt like a Utopian music scene. There didn’t seem to be any egos involved. There was an aura of the ideal of the hippie scene that could actually come to fruition through music. And it seemed to permeate the whole town. Everywhere you went, there was this camaraderie and this easy flow of relationships.”

The D.I.Y. nature of Mud Acres and the Mountains Revue reflected the challenge of sustaining careers as folk musicians in the seventies and eighties. Half the reason these Village and Cambridge veterans had moved to Woodstock was its affordability. Most weren’t naturally ambitious. Paul Siebel, one of the most admired singer-songwriters on the Village scene of the early sixties, plugged into the Traums’ circle but was diffident about playing live. “He was a brilliant songwriter, but he never performed,” says Jeremy Wilber, who served him at the Sled Hill Café. “He was not rolling in any sort of dough; he was just shy about performing.” Though Linda Ronstadt and Bonnie Raitt covered “Louise,” his poignant song about prostitution, Siebel was depressed that his idiosyncratic country-folk style hadn’t earned him more than cult status. Not even the bigger budget that Elektra allocated for 1971’s Jack-Knife Gypsy stopped him sliding into heavy drinking. When he showed up for the Woodstock Mountains sessions, he didn’t bring a single original song with him.

The music scene was equally difficult and painful for John Herald, who’d played such a part in bringing folk singers up to Woodstock in the sixties. “It really was hard on John,” says Jim Rooney. “There was a group of Woodstock people that had some success, but there was another that didn’t and was living hand-to-mouth. And it’s no fun to live in a wintry place when you’re broke. Ultimately he just couldn’t take it—year after year of being told how talented he was and yet not being able to pay the bills.” For Larry Campbell, Herald’s tragedy was that he could never get out of his own way: “So many people tried to help him—chiefly Happy and Artie, who bent over backwards to get him some stability—but rather than take responsibility for the gift he had, he waited for somebody to come and offer him the world for it.”

“I still like the ‘back-to-the-country’ idea, country music,” Herald told the Woodstock Times in 1996, “some things Woody Guthrie might have talked about.” After the release of his final album, 2000’s Roll On John—featuring “Woodstock Mountains,” a plaintive song about his ex-wife, Kim Chalmers—things deteriorated still further for Herald. In the early hours of July 19, 2005, after mailing farewell letters to friends, he took his own life.

ALMOST AS RETICENT as Paul Siebel were fellow folkies Fred Neil and Karen Dalton. Neil had returned to his beloved Florida by the early seventies, but from 1970 onwards Dalton spent much of her time in Woodstock. “I think it was Freddy who brought her up there,” says Harvey Brooks, who’d played on her 1969 album It’s So Hard to Tell Who’s Going to Love You the Best. “That was a big part of it—getting away from the city, and maybe away from your demons.”

Dalton had been fleeing those demons for years. With her sometime partner Richard Tucker she would spend months out in Colorado, only for Tim Hardin to show up and kick off her heroin addiction all over again. “Tim and Karen hung out together a lot,” says their friend Peter Walker. “They were just friends, really. Or shooting buddies. They saw each other up here in Woodstock.” Dalton sang several of Hardin’s best songs and may have been the first person to perform his “Reason to Believe.”

In his Chronicles, Dylan called Dalton his “favorite singer in the place,” while Fred Neil declared she was his “favorite female vocalist.” (The three of them were pictured together in a famous photograph taken in early 1961, most likely at the Café Wha?) An Amazonian beauty who’d acquired an unwanted reputation around the Village as “the hillbilly Billie Holiday,” Dalton preferred to sing privately or jam in her kitchen with friends. “She’s disappeared now,” Fred Neil told Hit Parader magazine in 1966. “No one knows where she is.” Nor did Dalton care for recording, which was why producer Nik Venet virtually had to trick her into cutting It’s So Hard to Tell Who’s Going to Love You the Best by inviting her to drop in on a Record Plant session by Neil. Her harrowing performances reached back to her public-domain bluegrass roots. Her voice was horn-like, elemental, and sparing of vibrato, each note a piercing straight line to the soul. “She wasn’t Billie Holiday,” Venet said, “but she had that phrasing Holiday had and she was a remarkable one-of-a-kind type of thing.” On “Ribbon Bow,” the aching plaint of a poor country girl who lacks the fineries of her big-city rivals, one heard the junkie stance in her every phrase and intonation.

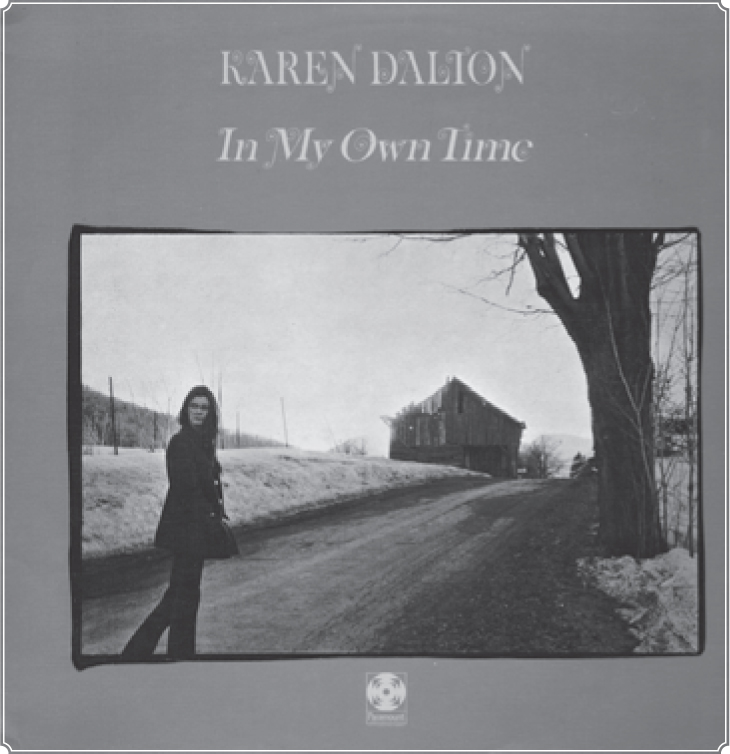

Holy Modal Rounders singer Peter Stampfel, who acknowledged her as “the only folk singer I ever met with an authentic ‘folk’ background,’” claimed Dalton had been in the hospital before moving to Woodstock with her two teenage children. Michael Lang signed her to his new Just Sunshine label, for which Harvey Brooks produced her second album at Bearsville, drawing on a pool of musicians that included Bill Keith, Amos Garrett, John Simon, and Full Tilt Boogie members Richard Bell and Ken Pearson.**

Lang says of the In My Own Time sessions that Dalton “was introspective and damaged but very pleasant to work with.” The album was a mixed bag: polarized between the stark bluegrass of “Katie Cruel” and “Same Old Man” on the one hand, and the slightly awkward covers of soul staples “How Sweet It Is” and “When a Man Loves a Woman” on the other, it was—barring horn overdubs recorded in San Francisco—pure Woodstock. Dalton even posed for photographer Elliott Landy on the town’s snowy back roads, elegant and graceful if somewhat ravaged. In places the album sounded like the Band, not least on its dreamy cover of their “In a Station.” More troubling was the version of her friend Dino Valenti’s “Something on Your Mind”—with its nod to the junkie life in the line “who cannot maintain must always fall”—while the closing cover of ex-beau Richard Tucker’s “Are You Leaving for the Country?” spoke for all those who, like Dalton herself, dreamed of leaving the city’s “iron cloud” behind and moving to a “little country town / where dogs are sleeping in the cold and the flagpole’s falling down.”

The track that brings most people back to In My Own Time is the darkly chilling—and terrifying beautiful—“Katie Cruel,” with Dalton’s banjo accompanied only by Bobby Notkoff’s spooky electric violin. She had been singing this traditional song for years, and it’s hard not to hear it as the adopted autobiography of a fallen woman. (There’s long been a rumor, incidentally, that the Band’s “Katie’s Been Gone” is about Dalton.) To newcomers, the timbre of her voice can come as a shock; some even find it hard to get past the catch in the throat that starts every phrase she sings. “If I was where I would be, then I’d be where I am not,” the voice of “Katie Cruel” sings with a kind of despairing Zen logic. “Here I am where I must be, where I would be I cannot.”

Karen Dalton’s second album, recorded mainly at Bearsville in 1970–1971

Peter Walker recalls seeing Dalton regularly at the home of their mutual friend Bob “the Brain” Brainen on the Wittenberg-Glenford Road. “Bob was one of those people who kept a musical open house,” Walker has written. “For years, whoever was in town would be up there hanging out: Freddy Neil, Tex Koenig, Tim Hardin, Bob Dacey, Becky Brindel, Bruce Gibson, Bob Gibson and a host of others gathered in the wee hours of the morning to share music, a beer, a bowl, and more music.” According to Walker, Brainen “took care of [Karen] and tried to get her to reform.” But when Michael Lang packed her off to Europe as a support act on a Santana tour, she imploded. “Mike hired John [Hall], with Bill Keith on bass and Denny Sidewell on drums,” says JoHanna Hall. “Most nights they did not get a sound check, and every night Karen got booed. And John would find her in the morning crying: ‘I can’t take it, I can’t take it . . . ‘So finally one night they were in Montreux, and she said, ‘I’m not going on, I’m not doing it.’ They had two thousand people sitting there.” On a later occasion, when Dalton had a gig at Woodstock’s Joyous Lake, JoHanna accompanied her into town: “She went onstage with her back turned to the audience, and I think she sang one song and just walked off. She was a very delicate flower.” Dalton was happier sitting around the Halls’ living room on Ohayo Mountain Road, singing Hardin’s “Misty Roses” with John backing her on guitar. “That was the kind of thing that would happen then,” JoHanna says. “It was such a shining moment.”

As the years went by, Dalton divided her time between Woodstock and a rent-controlled apartment in the Bronx. Though her life remained chaotic, she maintained a stability of sorts upstate, even after contracting AIDS. Peter Walker remained a loyal friend. “I knew she was struggling to keep her apartment and would make small money passing out fliers and doing other subsistence work,” he wrote. “At the end of the week when I would be leaving, she would come downtown and be ready to go back to Woodstock.” In the late eighties, a friend who’d been sentenced to a jail term gave Dalton the keys to his house on Eagles Nest Road in Hurley. It had a woodstove and a heated swimming pool. “She was there for quite a while,” says Walker, “all the time people thought she was suffering and dying on the streets of New York. She had a good sense of what kept her healthy.”

At the very end of her life, Dalton moved into a trailer on the same road. Rebuffing attempts by Kingston services to force her into a hospice, she died in the trailer on March 19, 1993—thirteen years after Tim Hardin fatally overdosed in Los Angeles and eight years before Fred Neil died of cancer in Florida.

![]()

* After we’d finished lunch, Lasdun asked if I was interested in seeing David Bowie’s apple orchards, which were half a mile up the road.

* Before moving to Woodstock, Eric Kaz played with Happy and Artie Traum in a New York band called the Children of Paradise. He later had several songs—including the coauthored “Love Has No Pride”—recorded by Linda Ronstadt and Bonnie Raitt.

* Von Schmidt, who had spent time in London with Grossman and Bob Dylan in January 1963, was another beneficiary of Bearsville studios, recording his 1972 album 2nd Right, 3rd Row there with the aid of the Muldaurs, Paul Butterfield, Amos Garrett, Graham Blackburn, Jim Rooney, Garth “Campo Malaqua” Hudson, and more—as well as a second album, Living on the Trail, which didn’t appear until 2002.

* Tony Brown later became a member of Eric Weissberg & Deliverance, playing bass on half of Dylan’s revered 1975 album Blood on the Tracks.

* Lang’s label, bankrolled in a production deal by Gulf & Western’s Paramount division, was also home to Brooks’s Woodstock-based band the Fabulous Rhinestones and the pop-gospel group Voices of East Harlem, as well as to Betty Davis, who’d steered her husband, Miles, toward the avant-funk of 1970’s Bitches Brew—on which Brooks played bass—before she recorded two lewd funk albums of her own for Lang. “The first two acts were Karen and Billy Joel,” Lang says. “Harvey suggested Karen, and then the Rhinestones came together. The label lasted through 1974, when Gulf & Western sold Paramount.”