IN THE FALL of 1997, Sally Grossman pokes at a plate of Chinese food in the Little Bear, a stone’s throw from an abandoned video studio built by her late husband for Todd Rundgren, and talks to me about the goofy whiz kid who first showed up in their world in the summer of 1969.

“Todd was this boy wonder,” Grossman says. “To be such a renaissance man at the age of twenty-one was very striking. We were spoiled, of course, because we were so used to brilliant people. But he was like all of them; his talent was already full-blown. It wasn’t like you heard him and thought, ‘Gee, with the right songs and the right producer . . .’”

In truth, Albert Grossman was less convinced than his wife by the Philadelphia prodigy who’d tasted fleeting pop glory in a British invasion–influenced band called Nazz, and whose whole sensibility—musical and sartorial—was so different from the earthy country-funk of the artists Grossman loved. Rundgren had slipped into Grossman’s world through the auspices of Michael Friedman, who’d worked with Nazz prior to being hired by Myra Friedman (no relation). “Albert was amenable to Todd but not very excited,” Michael confirms. “I think he felt Todd didn’t really fit in with the type of operation that he offered.” Rundgren, however, kept coming to the East Fifty-Fifth Street office, often falling asleep in reception there. “One day Albert said, ‘You’ve gotta get that kid outta here,’” says Friedman. “So I decided I would try and get Todd some production projects.”

When he heard what Rundgren could do in a recording studio, Grossman changed his tune. “I knew Albert was supposed to be this Allen Klein kind of guy,” Rundgren says. “It wasn’t too long before he started to see something in me.” Lucinda Hoyt believes Grossman became “a paternal figure for Todd, just as he had been for Bob and for Paul Butterfield.” The very first album released on Grossman’s Ampex label was the eponymous release by a power-poppish group from Rundgren’s hometown, produced by him at New York’s new Record Plant studio in August 1969. The American Dream was managed by Paul Fishkin, who was palling around with Rundgren in New York. “Todd said he was involved with Albert and wanted to produce the American Dream for the new label,” says Fishkin. “So it was like, ‘Okay, not only is my band gonna have a record deal without me even trying, but it happens to be with the god of all managers, the untouchable king of everything.’”

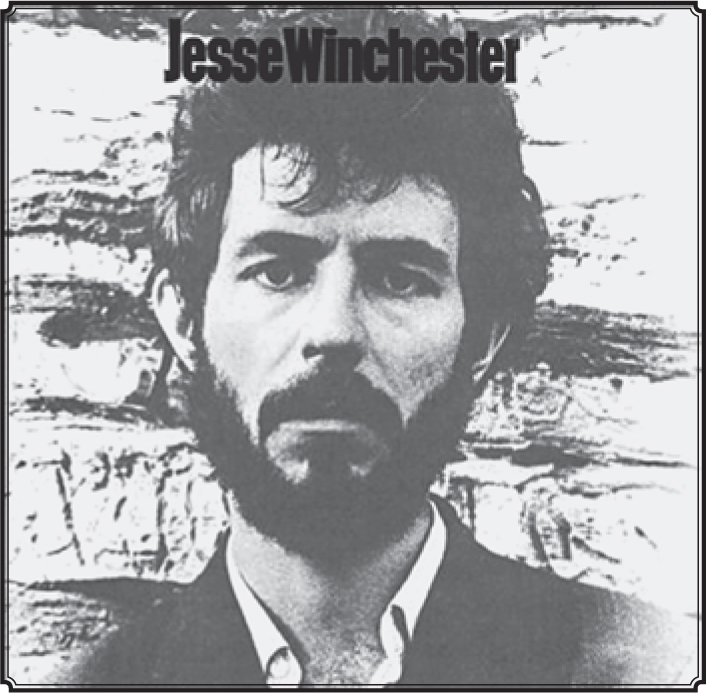

Rundgren also accompanied Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm to Toronto to tape the debut album by a Southern draft-evader who had fled to Canada in 1967. Jesse Winchester had been making a demo tape of his crisp and literate songs in Ottawa when Robertson dropped by to listen. The Band guitarist not only persuaded Grossman to sign him but heeded his manager’s advice to take Rundgren along as the engineer. “I think Jesse Winchester was a kind of run-through for [Stage Fright],” Rundgren recalled. “I was pretty quick to get the sounds, and they liked that.” Though it was more singer-songwriter-poetic than The Band, Jesse Winchester was still a close country cousin to that album. On the stare-you-down, Walker-Evans-style cover portrait, the bearded singer even looks like a cross between Levon Helm and Richard Manuel, with whom he shared a drinking problem that Paul Fishkin soon encountered on a visit of his own to Winchester’s adopted hometown of Montreal. “The first night I got there, Jesse was playing a gig at a college,” Fishkin says. “He was starting to catch on up there, but all of a sudden he went into this insane alcoholic rage in the middle of a song and walked off the stage.” This didn’t stop Fishkin believing in the talent of a man later recognized by his peers as a songwriter of great depth and subtlety: “There was a lot of potential to turn him into something really special, but it just wasn’t in him to become a big star.”

Jesse Winchester’s 1970 debut for Bearsville/Ampex, produced by Robbie Robertson and engineered by Todd Rundgren

Back in the United States, Rundgren—whose production of Winchester’s Third Down, 110 to Go was reduced to just three tracks**—continued functioning as Albert Grossman’s pet producer of choice. After recording the Butterfield Band at L.A.’s Troubadour, he worked with them again on aborted sessions for Janis Joplin’s third album. But as he had done with Ian Tyson in Nashville, he was beginning to piss people off. “He and his girlfriend Miss Christine were making faces behind Janis,” says JoHanna Hall. “He was very arrogant and obnoxious, and I thought he was making fun of her when I felt very maternal towards her.” In truth, Rundgren was merely frustrated by fellow musicians apparently more interested in drink and drugs than in their music.

The same thing happened during the Stage Fright sessions at the Woodstock Playhouse. The painfully slow pace at which the Band worked made that album “one of the more maddening experiences” Rundgren had had to date. “They were hillbillies, or at least trying to sound like hillbillies,” he says. “I remember the dichotomy of trying to do something that sounded concertedly folksy and creaky and dusty and not slick, and then at lunchtime Levon saying, ‘Hey, order me one o’ them Lobster Thermidors!’ They had the best of everything, and they had it both ways. And that was the germ of their demise.” Helm in particular was riled by the St. Mark’s Place androgyne with his green hair and loon pants. Michael Friedman recalls the Band drummer chasing Rundgren around the Playhouse, enraged by his addressing the narcoleptic Garth Hudson as “Old Man.” More sympathetic to Rundgren was the visiting Patti Smith, who was similarly bored by rock’s pervasive hedonism. “We were both misfits, both wiry, skinny, hard-working people who didn’t quite fit in,” she says. “Neither of us was involved in drugs or anything at the time, so it was a relief to meet someone to talk to where you didn’t have that kind of peer pressure to worry about.”

Bruised by his experiences in Nazz, Rundgren was happy to sacrifice his own musical ambitions for a burgeoning career as a producer. By the early summer of 1970, however, he felt the creative itch and asked Grossman for a budget to record an album in Los Angeles. “I’d never thought of myself as a singer,” he says, “but I continued to write as I had done in Nazz. I thought, ‘There are other things to be written,’ and I was very inspired by Laura Nyro and the possibilities of what you could say in a song.” Using the sons of TV comedian Soupy Sales as his rhythm section, Rundgren cut Runt at I.D. Sound Studios on La Brea Avenue. Right off the bat, he proved he could turn his hand to anything he wanted: trashy rock (“Who’s That Man?”), good-humored pop (“We’ve Gotta Get You a Woman”), and bittersweet Brian Wilson balladry (‘“Believe in Me”). Here were most of the blueprints for Rundgren’s styles, stirred into a pot by an impish wizard not unlike the one pictured on the album’s sleeve. Back in New York he added three tracks at the Record Plant, one of them (“Once Burned”) surprisingly graced by the rhythm section of Levon Helm and Rick Danko. “I was imitating Richard Manuel on that song,” Rundgren has claimed, “so I thought, ‘Why not get Levon and Rick to play on it?’”

Another of the Record Plant tracks was “I’m in the Clique,” a swipe at the in-crowd snobbery endemic in both Manhattan and his manager’s social circle in Woodstock. “I was really punky about that,” says Paul Fishkin, for whom the song also spoke, “because I had an attitude towards all Albert’s Woodstock groupies and sycophants. There was a certain better-than-thou pretension in that whole era, and Todd and I had fun goofing on it.” It was Fishkin, too, who inspired the song that gave Rundgren his first solo hit at the tail end of 1970. Based on their shared experiences of girl watching (or frustrated lusting) from the stoops of St. Mark’s Place, “We Gotta Get You a Woman” was a perfect piano-pop song that made the top 20—despite enraging a number of feminists with a silly line about women being “stupid” but “fun.”

BY THE TIME Rundgren’s second album came out in June 1971, Grossman had made the decision to leave Ampex for Warner-Reprise. Ever since the signing of Peter, Paul & Mary in the early sixties, Warners head Mo Ostin had watched as Grossman signed act after act to rivals like Columbia; there was even a rumor that Grossman had intended to offer the Band to Ostin but had gone to Capitol after learning that he was out of town. “We made the deal,” says Fishkin. “And as bad and stupid as the Ampex deal had been, the Warners deal was genius.”

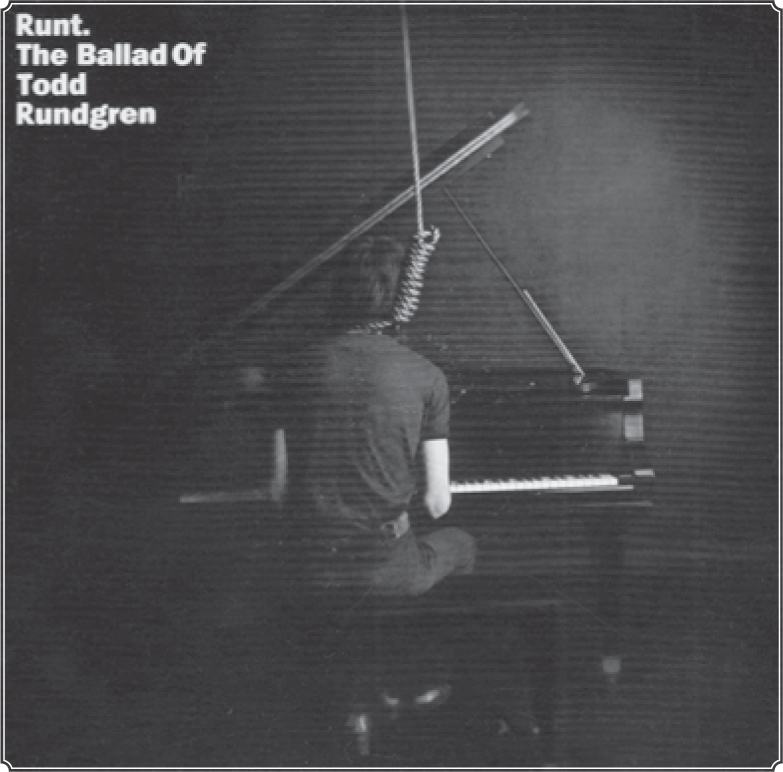

A casualty of the transition, unfortunately, was The Ballad of Todd Rundgren, a collection of bittersweet ballads whose basic tracks were again recorded at I.D. Sound. When N. D. Smart II arrived at Rundgren’s rented house off Nichols Canyon, he found a wooden gallows in the living room. “I think it’s because somebody said, ‘We’re gonna give you enough money to hang yourself with,’” Smart remembered. The noose was duly featured on the cover of the Ballad album in a design by Milton Glaser, with Rundgren’s back to the camera and the rope around his neck. In an age of winsome singer-songwriters, it wasn’t the smartest image to project.

If Grossman was disappointed that The Ballad produced no hits, consolation came in the fees he was now able to command for Rundgren’s production skills. In September 1971, the boy wonder flew to London to take over Badfinger’s Straight Up album from George Harrison. According to the band’s Pete Ham, Rundgren “wanted four times the money he deserved.” It was Grossman, however, who’d demanded it. “He asked for a shitload, more than any producer had ever been paid,” Rundgren says. “And they paid it because it was Albert Grossman.” Like Joplin and the Band before him, Badfinger’s Joey Molland found Rundgren to be “rude and obnoxious.” Michael Friedman says “the problem with Todd was that he was so difficult to work with that he almost never got to do a second album with anybody.”

Failure though it was, The Ballad indirectly wove Rundgren deeper into the fabric of Woodstock. The album’s exquisite multitracked vocals, for instance, were recorded at Bearsville’s Studio B. “When the studio got running, this kid came in with long hair and took all my down time,” says Jim Rooney. “He’d be in there all night long all by himself.” Grossman told Rooney that Rundgren would be the most important artist of the seventies, and others felt the same way. “He could have been the biggest artist of the era,” Paul Fishkin maintains. “If he’d taken a little more time to work with me, there’s no question in my mind that we could have had it all.” They very nearly did after 1972’s sprawlingly ambitious double album Something / Anything? delivered the power-pop hit “I Saw the Light” and then, a year later, a top 5 remake of the Nazz’s “Hello It’s Me.”

Less supportive by this point was Michael Friedman, who was nurturing a new Bearsville artist named Jesse Frederick. “Todd didn’t appreciate anything, and I’d really stuck my neck out for him,” Friedman says. “I think he felt that I’d deserted him for Jesse, but I stopped being interested because he was pissing people off and I was putting my name on it. He was a good engineer, but I preferred John Simon’s productions. With Todd, everything was sort of molded after the Who and the British sound, which was a much harsher sound than the funky Southern blues style the Grossman artists were involved with.” More appreciative than Rundgren, Frederick moved into Friedman’s house in Shady and began rehearsing for an album made at the same Nashville studio where Great Speckled Bird had been recorded. 1971’s Jesse Frederick—rootsier and more soulful than The Ballad of Todd Rundgren, though hardly as original—was the first Bearsville album released under the label’s new Warners deal, while the second was a soft-rock effort by three long-haired Christians calling themselves Lazarus, produced at Bearsville by Peter Yarrow. The third in the Reprise 2000 series—not counting reissues of Rundgren’s first two albums and of Jesse Winchester—was by eccentric Los Angeles duo Halfnelson, produced by Rundgren after he’d been introduced to them by Miss Christine. When Grossman suggested they rename themselves the Sparks Brothers, Ron and Russ Mael reluctantly compromised on Sparks, though success only arrived when they later signed to Island in London.**

Though Something / Anything? became the favorite Todd Rundgren album of many fans, it was never meant to be a double LP. “It was pretty much going to follow along the lines of Ballad,” he says. “But it just went and went and went, fueled by pot and Ritalin. The first three sides were done in three weeks. I was, like, Mr. Music.” Something / Anything? was a conscious display of tricks, flaunted with the chutzpah of a rock and roll jester. One minute Rundgren was the hard rocker of the slow, mesmerizing “Black Maria,” the next the power-pop brat of “Couldn’t I Just Tell You.” On the album’s fourth side, he returned to Bearsville to record with various alumni of the Full Tilt, Butterfield, and Great Speckled Bird bands: Amos Garrett, Jim Colegrove, Billy Mundi, Bugsy Maugh, and Gene Dinwiddie. The tracks coincided with Rundgren’s decision to leave California for good. “He slept on my sofa,” says Colegrove. “He was different from all those people because he had no folk or country roots.”

In February 1972, Rundgren began a relationship with a ravishingly pretty eighteen-year-old that would last five stormy years. For Bebe Buell, he was close to being a father figure, while for him she became the conduit to a hipper-than-thou New York scene he would never have embraced on his own. Inevitably he introduced Buell to his manager, bringing her to Bearsville. “The first time I met Albert, we went up for one of these amazing teepee parties he used to have,” she remembers. “It was meant to be a bit of a spiritual moment, though it usually just turned into people going off and fucking.” An early intimation of the relentless infidelity she would suffer—as well as perpetrate—came when Buell caught Rundgren with Lucinda Hoyt in the Grossmans’ kitchen. After Grossman found her weeping in the teepee, she explained why. “Yeah, the guys really seem to like Cindy,” he blithely replied.

To Buell, Grossman was like Santa Claus. “We were always going over to his house and eating good food,” she says. “He would have Todd over or Butterfield, and everybody would talk turkey. There was always a lot of discussion and debate.” Though he’d disengaged from the day-to-day business of management, Grossman assiduously maintained his mystique. “The first time I met him was probably in October ’71,” says Paul Mozian, who became another of Grossman’s tour managers. “I was working for Allen Klein, and Albert shows up in the office for a meeting with Allen’s accountant to negotiate something for the Concert for Bangladesh album. He’s wearing a gigantic fur coat, so this assistant says, ‘Mr. Grossman, shall I take your coat?’ To which Albert says, ‘No, that’s fine,’ walks into the office, and throws it on the floor. I said to him, ‘You really threw the guy off.’ And he said, ‘Well, that’s the purpose, isn’t it?’”

Grossman had a problem, though. He might have been a fearsome kingmaker as a manager, but he didn’t quite grasp what it took to run a record company. “The label never really became what Albert envisioned,” says Michael Friedman. “He was going to have all his bases covered, and he would get income from every area imaginable. It was a brilliant concept, but the Band didn’t want to leave Capitol, so the label never went anywhere. Todd had a couple of hits, but Jesse Winchester never really took off. You needed to have hit records, and Albert didn’t know what hit records were. He just knew what hit artists were.”

It was galling to Grossman that the first and only really big success chalked up by Bearsville Records came with Foghat, a meat-and-potatoes boogie band that Paul Fishkin signed from England. “It was like a cruel joke of fate,” says Danny Goldberg. “Here was the ultimate music snob having a hit act with a band that had zero snob appeal.” Graduates of sixties Brit-blues stalwarts Savoy Brown, Foghat hit gold with their third album Energized (1974) yet almost never recorded at Bearsville. In Grossman’s eyes, there was nothing classy about front man “Lonesome Dave” Peverett and his hairy henchmen, even if he liked the money that rolled into Bearsville’s coffers from albums like Fool for the City and singles like “Slow Ride.” “Bearsville was a small company and a young company,” Peverett said in 1995. “[Albert had] sort of almost semi-retired. He pretty much left it up to Paul Fishkin, and Paul, in conjunction with a budding agency, was the secret to our developing a following.”

As snobbish as he felt toward Foghat, Grossman valued Fishkin and admired his refusal to genuflect to him. “For whatever reason, I had no fear of Albert,” Fishkin says. “And I watched so many people around him fall by the wayside because they were doing what they thought they had to do.” Increasingly Grossman leaned on the younger man to steer the wayward ship that was Bearsville Records. “I’d become the cliché of the hip rock and roll executive working twenty hours a day,” Fishkin says. “Albert loved that I was working so hard, but he was very frustrated I wasn’t doing it on his terms. He really wanted me up in Bearsville more, but the phones never worked right, and it would get flooded out.”

Grossman’s dependency on Fishkin was sorely tested when, in 1973, David Geffen headhunted the younger man to run his Asylum label in California. To keep Fishkin on the East Coast, Grossman offered him a third of Bearsville Records’ stock. A year later, when Steve Paul tried to poach him for his Blue Sky label, Fishkin received a further 15 percent. “The truth was that Albert never thought Bearsville was going to make any money anyway,” says Fishkin. “I later found out he was borrowing tons of money against the label to build his empire.”

That “empire” was itself fraught with complications and difficulties. Grossman’s constant equivocation—and his tendency to start new projects before older ones had been completed—had become almost pathological. “There seems to be a general view that Albert was a bit of a bastard, but he was a lot more complicated than that,” says John Holbrook, who was now working as a live-sound man for Todd Rundgren and Paul Butterfield. “The frustrating thing was that he wouldn’t commit to anything. It was always like, ‘Well, we’ll have to just see . . . I dunno, y’know?’”

The pressure on Grossman’s employees was palpable as he green-lit one initiative after another. At the studio, Jim Rooney suffered constant headaches as a result of the stress. When Paul Cypert told him, “I’m not dealing with [Albert] anymore,” Rooney wondered if it wasn’t time to quit. Mark McKenna recalls that Grossman even had plans to build his own TV studio: “He was in discussion with developer Dean Gitter about getting a signal. Albert wanted to control his environment so much that he built a fucking town around himself.”** Grossman’s scattergun approach to real-estate development has its defenders. Jerry Wapner, the Woodstock lawyer who’d tried to manage Tim Hardin, contends that Grossman brought only good things to the town. “He was an interesting man and a great client,” Wapner said. “The people who attacked him are the same people . . . whose base response consisted of a fear of anything new. [And] that he was powerful and wealthy didn’t help much.”

With the studio’s wrinkles finally ironed out, Grossman now focused on the Bear Café—the 1973 successor to his failed French restaurant—and on his plans for a Bearsville Theatre.** “The warm-up was the Bear, but the theatre became a huge project,” says John Storyk, who moved to Woodstock to work full-time for Grossman after returning from a stay in Colorado. Like the Bearsville studio, however, the theatre was soon causing major headaches. “The problem was that Albert wasn’t a town planner,” says Michael Friedman. “He couldn’t put all the pieces together effectively. He would jump from one person to another, whoever was reflecting in his aura at that moment. If he’d had the sense to use professional people on the theatre, it might have turned out differently.”

Through all this feverish and not always effective activity, Grossman never lost his ability to astonish. When Friedman brought New Orleans legends Snooks Eaglin and Professor Longhair to Bearsville to make an album, Grossman took the tapes off him and then called to say he was giving them to Robbie Robertson. “I said, ‘Why?’” Friedman recalls. “He said, ‘I think it would be good for Robbie.’ I said, ‘Maybe it would be good for Robbie, but so what.’ And he never put the record out.”

Worse still was the treatment meted out to former Electric Flag keyboard player Barry Goldberg, who came to visit Grossman with his new wife, Gail. “We took the bus up, and it was snowing, like six inches of snow,” Goldberg says. “We got there about five in the afternoon and trudged through the snow. And we congregated in the kitchen, and Albert brought out the cheese and the salami.” Just as Goldberg was starting to wonder when he and Gail would be shown to their quarters, Grossman turned to him and said, “By the way, where are you staying tonight?” When Goldberg gasped in disbelief, Grossman explained that the guest bedroom was unavailable and that no one was allowed in Janis Joplin’s old room. “He said to me, ‘You’re a big boy now, Barry—you have to figure it out for yourself.’ I broke into a cold sweat. We were stranded.” Adding insult to injury, Goldberg’s old Chicago homeboy Paul Butterfield also turned him down because his cat had just given birth to a litter of kittens in the spare room.

In the end it was the sainted Jim Rooney—who’d never even met Goldberg before—who put Barry and Gail up for the night. “I got really sick that night in the snow, because I couldn’t believe what was happening,” Goldberg says. “But Albert had that side to him. He loved to play games. He was always calculating.”

![]()

* Not including the sublime “Dangerous Fun,” a song of carnal temptation that’s among Winchester’s absolute best.

* Following the 1971 release of Halfnelson, Miss Christine left Rundgren for Russ Mael, the more conventionally handsome of the two Maels. She was the subject of the Flying Burrito Brothers’ unflattering “Christine’s Tune” and a member of Frank Zappa’s protégées/nannies/groupies Girls Together Outrageously. In November 1972 she died of a heroin overdose.

* Grossman and Gitter went way back: the latter had produced Odetta’s debut album for Riverside and recorded his own Ghost Ballads (1957) for that label. Later settling in the Catskills, Gitter became a classic Woodstock combo of entrepreneur and spiritual seeker, as well as an unrepentant folkie—as his 2013 album Old Folkies Never Die attests.

* The Bear took its name not just from Bearsville itself but from a club—run by Howard Alk—that Grossman had opened in Chicago in the early sixties.