WHILE THE CLUSTER of musicians around Albert Grossman dominated the Woodstock of the early seventies, another music community evolved in parallel to it. Yet the local avant-jazz scene was all but hidden from general view. “There are many musical Woodstocks, which gets lost in history,” says Jonathan Donahue. “People come here hoping to see Janis Joplin’s illegitimate child belting it out on the village green, but I’ve always found myself mated to the more underground inspirations there. Even today, if you include the local area of Kingston, there’s Karl Berger; there’s Pauline Oliveros; there’s a lot of orchestral writers. And that’s what’s always kicking against the pricks.”

Ed Sanders, who’d always kicked against the pricks, moved to Woodstock in 1973, drawn not by Albert Grossman but by the beauty of the place and the radicalism of its artistic heritage. “I came for the bluestone creeks and the history,” he says. “I had a very turbulent sixties, and you’ve got to wash ashore somewhere. There were other leftists and radicals that survived here, so I knew that I could too.” The immediate spur for Sanders’s relocation was the heat that followed the 1971 publication of The Family, his chilling account of the Manson murders. “I had these Satanic cults on my back, so my wife and I rented an old chicken coop out on Sickler Road,” he says. “Then I got a big royalty payment for the book, so we decided to use the money to buy a place. Blame Manson for me becoming a permanent resident!”

Sanders was pleased to find not just artists and musicians in Woodstock but a smattering of writers. “There was a big poetry scene going on when I moved up,” he says. “There were over a hundred poets and a big network of readings in coffee shops and bars.** Plus Philip Guston was still alive, and there were lesser-known lights who got money from Jimmy Carter’s CETA [Comprehensive Employment and Training Act] arts program. Karl Berger and others got government grants. There was a lot of creativity and ferment.”

Vibraphonist Berger and his singer wife, Ingrid Sertso, had come to New York from their native Germany in August 1966, having fallen under the spell of radical free-jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman. Initially homesick and disillusioned, the couple were dissuaded from leaving by Coleman himself. Though Berger played with the more radical figures in the New York and Brooklyn loft scenes—Archie Shepp, Roswell Rudd, and others—it was only when he and Sertso moved permanently to the United States in 1971 that they began to feel at home. Hatching the concept of the Creative Music Foundation, they moved to Woodstock with their young daughters the following year. There they established the Creative Music Studio, initially in Mount Tremper and then in a converted Woodstock barn on Witchtree Road, inviting their old loft friends from the city to stay and participate in formal music classes.††

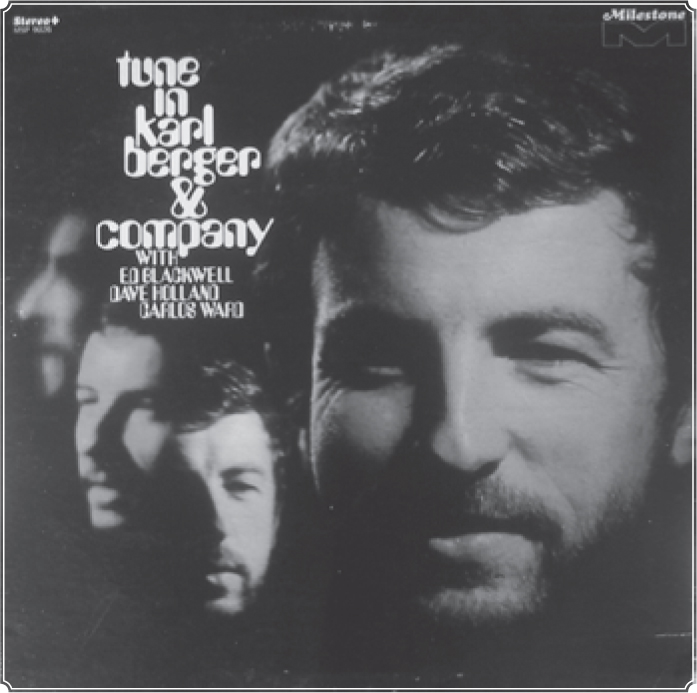

Karl Berger and company (1969)

It helped that there were already jazz players living at least part-time in the Woodstock area. Maverick violinist Betty MacDonald had made the town her home in 1969, while husband and wife Carla Bley and Mike Mantler had moved their rural base from Maine to a house-cum-studio in Grog Kill near Willow. Among the huge cast of players on Bley’s and poet Paul Haines’s epic 1971 “chronotransduction” Escalator over the Hill were Berger and Don Cherry—along, more improbably, with Jack Bruce and Linda Ronstadt. “Talk about someone who connected rock and jazz,” says trumpeter Steve Bernstein, who recorded at Grog Kill in the early eighties. “Carla was really one of those people meeting people from both scenes.” Two of the key sidemen on Miles Davis’s revolutionary albums In a Silent Way (1969) and Bitches Brew (1970) now also made their homes in Woodstock: English bass player Dave Holland was in Mount Tremper, while drummer Jack DeJohnette lived in Willow with his wife, Lydia. Harvey Brooks, another of Davis’s musicians, similarly straddled the spheres of Woodstock’s rock and jazz scenes and befriended both Holland and DeJohnette.

Woodstock proved fertile for serendipitous hookups. John Simon remembers driving along Tinker Street with folk-bluegrass singer-songwriter John Hartford when they spotted Dave Holland lugging his laundry back from Sam’s Laundromat. “We stopped and said, ‘Hey, Dave, wanna play bass on a bluegrass album?’” Simon says. “He said, ‘What’s bluegrass?’ But he signed up for it anyway.” Recorded at Bearsville, Hartford’s Morning Bugle album came out in June 1972 and was, says Simon, “the kind of thing that could only have happened in Woodstock.”

Holland was just one of the illustrious “guiding artists” at the Creative Music Studio, a place of refuge for battle-scarred jazz veterans. Established by Berger and Sertso with the help of their great free-jazz mentor Coleman, CMS took root in the fall of 1972. “Ornette never came up, but he was basically the spirit behind it,” says Berger. “I asked him why he wasn’t coming to teach, and he said, ‘If I came to teach, people would think I know something!’” The Bergers relished the fact that jazz factions prevalent in New York seemed to break down in Woodstock: alto saxophonist Lee Konitz jammed with violinist Leroy Jenkins, bassist David Izenson collaborated with flautist-composer Harvey Sollberger. “People were more relaxed up there,” Berger told Ludwig Van Trikt. “They didn’t think in terms of the PR quality or the career situation or whatever it was.”

The Bergers’ nonhierarchical, nonbureaucratic approach to creativity was refreshing to the bolder spirits on the New York scene, as well as to such notionally mainstream players as Konitz and Jimmy Guiffre. Another participant was Howard Johnson, the tuba player who’d been a key member of the horn section on the Band’s Rock of Ages. Later came Don Cherry, who taught inspiring CMS classes through the summer of 1976, and the cerebral, pipe-smoking Anthony Braxton, who settled in his own place on Chestnut Hill Road. There were more intermittent visits from the minimalist Steve Reich and local composer Pauline Oliveros. “Some of the best people in the world would come . . . right to our house,” Berger said. “Also, all these musicians who lived in the Woodstock area at the time . . . were actually looking to do some work at home that was creative, and not have to be on the road all the time.”

Most of these remarkable player-composers had experienced the freedom of the scene in Europe and wanted to recreate it in the Catskills.** “The CMS became a woodsy outpost of the city’s loft scene,” Will Hermes wrote in his Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, “a sort of new-jazz ashram developing a tradition of freely improvised music that aspired, among other things, to draw every form of world music into its vocabulary.” Among the “world musicians” who regularly participated in the CMS were percussionists Naná Vasconcelos and Babatunde Olatunji, along with saxophonist Ismet Siral and the kora player Foday Musa Suso. “Even before you get to CMS, you know that your whole attitude is changing,” Olatunji told Robert E. Sweet, author of the CMS history Music Universe, Music Mind. “Coming from a city like New York, a concrete jungle, you pass through woodlands, you hear birds singing—it’s country. You become aware of all the things that nature has given us to admire that we seldom take a look at.”

To pianist Marilyn Crispell, who was closely involved with the Bergers between 1977 and 1982, CMS was “a totally unique place in the world . . . a hands-on experience, free and creative.” Indeed, the studio was almost an unmusic school: Dave Holland came to teach not bass playing but his own ensemble work. Albums such as his 1973 ECM release, Conference of the Birds, and Braxton’s 1976 work, Creative Music Orchestra, were rooted in the CMS experience. “It’s not like you go to a music school or conservatory and then you find these nasty, cranky teachers that have a job until they retire,” Ingrid Sertso said. “CMS was the opposite.”

“Karl and Ingrid were somewhere between Mom ’n’ Pop and gurus,” says Steve Bernstein, who took a CMS course in the summer of 1977. “They were like hippie parent figures, very spiritual and into Buddhism. They’d talk about things other people weren’t talking about, about enlightenment and pure sound and the power of rhythm.” Central to CMS “teaching” were breathing and body-awareness classes—not to mention Buddhist meditation, which Don Cherry had practiced for many years. Indeed, the Woodstock jazz scene became somewhat intertwined with the town’s alternative community. “Healers tell me that Woodstock is on blessed land,” says Lynne Naso. “Jack and Lydia DeJohnette became centerpieces of that community.” (The DeJohnettes were close to Robert Thurman, father of actor Uma and a leading American Buddhist whose Menla retreat is located in the mountains west of Phoenicia.) “My teaching was basic practice,” Berger says. “It started with the principle of sound and silence—and there was no silence in New York. Nature really helps, and from the start we had a rather spiritual approach to music. We wanted to make sure that music was understood not just as a business or as entertainment but as a lifeblood of mankind.”

In the fall of 1974, the Bergers moved CMS back to its original home of Mount Tremper, striking a deal with a Lutheran summer camp that enabled them to use an old monastery in the spring and fall. After two semesters there, they moved to West Hurley in the fall of 1976, taking over Oehler’s Mountain Lodge motel on forty acres of land. After initial teething problems—a culture clash between the musicians and the Lodge’s established German clientele—in 1977 the Bergers asked the Oehler family if they wanted to sell. Though it would become a financial millstone for them, the Lodge provided CMS with its first secure home. “We could really house people there year-round,” says Berger. “It became like a live-in college.”

During its late-seventies heyday there were eight-week CMS semesters in the fall and spring, along with two five-week semesters each summer. Many of the earlier “guiding artists” maintained their involvement with CMS, and there were poetry workshops held by Ed Sanders and Allen Ginsberg (who brought cellist Arthur Russell with him as a musical accompanist). There were also what the Bergers called “intensives” at Easter and at the turn of each year, the most celebrated of which featured the illustrious Art Ensemble of Chicago and—in the winter of 1979–1980—the wildly experimental pianist Cecil Taylor. “Students” such as Steve Bernstein, Marilyn Crispell, and multi-instrumentalist Peter Apfelbaum became part of the Bergers’ family, even when some of them became willing participants in Woodstock’s rock culture. “In the rewrite of jazz history, they make it seem like avant-garde jazz was this weird kind of phenomenon that ruined jazz,” Bernstein says. “But if you think about Hendrix and people like that, it was very related to Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders. There were a lot of crosscurrents between what young people wanted to hear, and that was really what CMS was about.”

With grants from the Ford Foundation and the National Endowment of the Arts, CMS was able to employ upwards of thirty people—a boom period for Woodstock arts that recalled Roosevelt’s Federal Art Project of 1935–1943. As fundraiser Marianne Boggs told Robert Sweet, “we really were running . . . more than a half-million-dollar organization, annually, out of those bizarre half-bedrooms over at Oehler’s.” Sadly the boom came to a crashing halt when—two years into the Reagan administration—all the programs set up by Jimmy Carter were slashed. With European students now obliged to attend the CMS as tourists, the Bergers were forced to close the studio in 1984.** The legacy of the CMS remains for all to see and hear, however. “The avant-jazz community grew pretty fast in the seventies, and some of the people who came up to study stayed here,” says Berger. “There are over forty or fifty musicians that came up then who still live around Woodstock.”

BERGER CONTINUES TO lead the Creative Music Studio Orchestra, comprised of former members and specializing in old pieces by Don Cherry, Ismet Siral, and others. “Peter Apfelbaum and I still play with Karl,” says Steve Bernstein. “The sad thing is that CMS doesn’t have a physical base anymore.” In 2011, downtown avant-jazz star John Zorn offered Berger a weekly series of CMS Orchestra shows at his East Village space, the Stone. In the same year, nonprofit label Innova released a compilation of archival CMS recordings from the late seventies and early eighties.

In the nineties, in need of steady income, Berger entered the groves of academe, teaching at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth and becoming dean of the music department at Frankfurt Conservatory. After the CMS years, he found the experience enervating. “The kids of the nineties particularly were very goal-oriented,” he said, “in the sense of having a profession, being music teachers, getting a diploma so that they could teach.” But he also found a new lease on creative life as a writer of arrangements for such artist-producers as Bill Laswell. “I got to know Bill as a nineteen-year-old who was starting to produce in New York,” he says. “A few years later I had this idea: Why can’t we have strings playing rhythmic lines like horn sections in funk productions? He loved the idea, and we did many records for Sly & Robbie and Yellowman, over fifty albums.”

Through Laswell’s association with Sony/Columbia, Berger was brought to the attention of one of the label’s rising stars. “They invited me to write for Jeff Buckley at Bearsville,” he says. “It turned out that he was one of those CMS-style guys who would listen to Shostakovich and Bill Evans and any kind of music he liked.” Footage of Berger with Buckley in Bearsville’s vast Studio A—and of Berger conducting members of the Hudson Valley Philharmonic as they played his swirling string arrangements—was included on the bonus DVD accompanying the tenth anniversary edition of Buckley’s Grace. In an interview for the DVD, Buckley described Berger’s work on the album as “kind of like a regal visitation.” Like so many before him, moreover, Buckley found Woodstock highly conducive to music-making. “I’ve lived in pretty rural places before, so this is familiar,” he told director Ernie Fritz. “The setting itself is great, but the best thing about it is that it’s outside Manhattan, and I’m an easily distracted person sometimes when it comes to the city. . . . [Woodstock] is a great place to get focused. It’s like a pirate ship. There’s nothing to do but make this ship sail.”

Along with the Creative Music Studio “graduates” who still call the town home, other jazz stars—from clarinetist Don Byron to the legendary Sonny Rollins—either reside in Woodstock or use it as a rural base to recharge their creative batteries. “At a time when I was very busy with sessions in the city, I’d come back here to decompress,” says Warren Bernhardt, who toured with Jack DeJohnette in the mid-seventies. Carla Bley is still in Grog Kill and was even lured out of her hideaway in April 1993 for a rare performance at the Bearsville Theatre. “It was a duo concert with her third husband, Steve Swallow,” says Mark McKenna, who booked the date. “She was reluctant, because she said she didn’t want the guy who plowed her driveway to have to come and see her in concert. But as it turned out, she loved it.”

For Karl Berger, the jazz scene in Woodstock—like its music community in general—is in a sad state. “There are so many musicians here, yet there’s so little music in town,” he says mournfully. “The musicians play all over the world, but they don’t play here. I haven’t seen Dave Holland or Jack DeJohnette play here in years. It’s really a sorry situation.”

![]()

* For more on the local poetry scene, see Perkins, “A Short History of Poetry in Woodstock.”

† Living just a few houses along on the same road was none other than Charles Mingus. “We didn’t know him that well, and he didn’t come by,” Karl Berger recalls. “He was mostly in a state of not being approachable.”

* For a perfect example of what one might term Woodstock’s bucolic fusion, listen to “Back-Woods Song,” the first track on the 1976 debut by Gateway, a trio comprising Holland, DeJohnette, and guitarist John Abercrombie.

* Though not before the Woodstock Jazz Festival, held in September 1981 in an adjacent field to mark the tenth anniversary of the birth of the Creative Music Foundation. The gathering featured performances by Anthony Braxton, Jack DeJohnette, Pat Metheny, Chick Corea, Lee Konitz, Howard Johnson, Naná Vasconcelos, and Marilyn Crispell.