IN A WITHERING critique of Woodstock published in September 1972 in Harper’s magazine, writer Peter Moscoso-Gongora declared that “the Woodstock pop-music boom is imploding, eating into itself, trying to stave off the entropy at its core.” The town’s streets, he wrote, were full of “sad, pathetic people, drawn to Woodstock by the myth,” while its few remaining stars wished these “street people” would “disappear somewhere, like under a rock.”

Moscoso-Gongora argued that once Dylan, Van Morrison, and others had left Woodstock, there was no one to take up the slack. He wrote of “engineers with newly-built studios, waiting for the boom that never came” and noted that both Albert Grossman and Mike Jeffery had “burned their fingers” with performers who were “too wiped-out to put an album together.”

“A series of cocky flak-catchers—John Gardner, Jim Rooney, Al Schweitzman, Jon Taplin, Mark Harman, all faceless—exist to keep people away from [Grossman] and say nothing about anything,” Moscoso-Gongora observed. “They can all be seen on a late night at the Bear Café next door to the restaurant, with its own kitchen and its own moniker: ‘The Cocaine Palace.’” John Simon told Moscoso-Gongora he couldn’t even go into town anymore. “Everyone is plying his tapes,” the former Band producer said. “You come up here for privacy and you’re bombarded by the lousy groups. The whole town is full of a bunch of poopbutt musicians. Muscle Shoals can offer backup musicians, Grossman’s studio can’t offer anybody.”

Outside the immediate orbit of Grossman’s mini-empire, however, the Woodstock scene continued to thrive. “There were some very good groups,” says Happy Traum, who released Hard Times in the Country, his third album with brother Artie, in 1975. “There were the Striders with Robbie Dupree, the Fabulous Rhinestones, NRBQ, Chrysalis, Billy Batson, and Holy Moses. You could spend a lot of time talking about all the interrelationships.”

“In those days you were able to cluster,” says Dupree. “Most of the bands had their own houses: the Rhinestones, my band, and a band called Crackin’ that came from the Midwest and were all set to go when Albert picked Bugsy Maugh to be Full Tilt’s new bass player.” At the Striders’ house on Glasco Turnpike, Dupree would regularly come home to find a new set of strangers sprawled on the couch watching TV. “They’d say, ‘Who are you?’ and I’d say, ‘I live here!’ So that was the vibe in Woodstock.” According to Dupree there was a circuit of at least ten decent venues in and around Woodstock—north to Albany and south to New Paltz, east to Saugerties and west to Hunter Mountain—and the Striders played all of them.

Still another homegrown outfit was Bang!, brainchild of former Cyrkle bassist Tom Dawes and briefly the employer of departed Butterfield Band guitarist Buzzy Feiten. “Tommy had worked in advertising and made a lot of money by coming up with the ‘un-cola’ campaign for 7 Up,” says Jeremy Wilber. “As a consequence he was forced to show up at the Sled Hill every afternoon with a snow shovel’s worth of cocaine just to keep those boys in the band. It was the most coked-out group anybody ever saw.”**

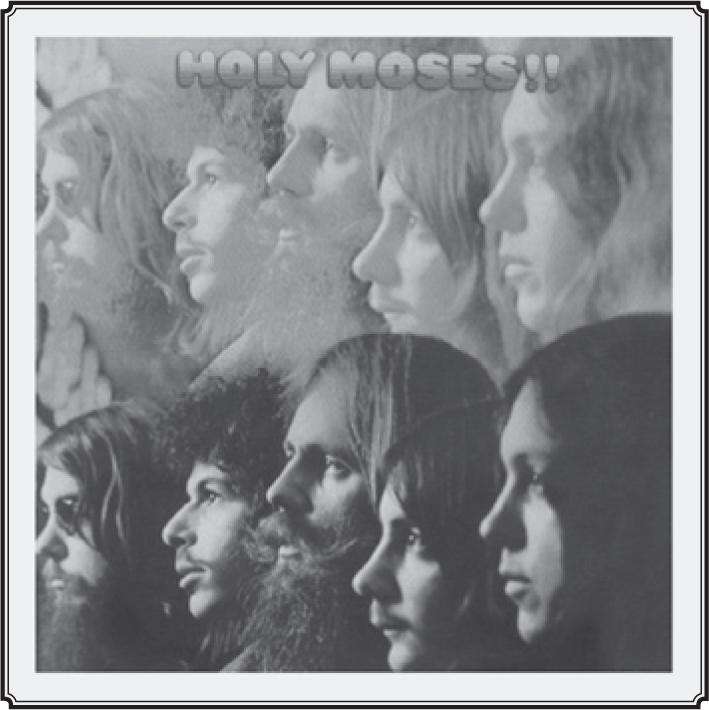

Also forming in Woodstock was Holy Moses, pieced together by guitarists Teddy Speleos and David Vittek with bass player Marty David. “The town was overrun by hippies and tourists and people sitting on the Green,” says Christopher Parker, whom Holy Moses had coaxed upstate to be their drummer. “There were multiple leather shops and candle shops, bakeries run by hippies.” Soon fronting Holy Moses was Billy Batson, who’d surfaced in Woodstock back in 1965 after leaving his native California. Gigging as a solo act at the Elephant one night in 1969, he hung around to catch Holy Moses and got chatting with them after their set. Moving from the Peter Pan Farm to Batson’s place on Ohayo Mountain Road, the band was scouted by Albert Grossman, who penciled in Rick Danko to produce their debut album. “They were kind of like the Band, real funky roots-rock stuff,” says Jim Weider. Before Grossman could get them in his clutches, however, they were spirited away from him by Mike Jeffery. “We saw Mike a lot, and he would come to rehearsals,” says Parker. “We had our own house on Wiley Lane with a bunch of different bedrooms and walking distance from the town. We played in all the clubs there, and we’d play Port Ewen, Saugerties, and Hunter Mountain.”

Blending heavy guitar rock with the Southern influences of the Band, 1971’s Holy Moses!! was recorded for RCA at Hendrix’s Electric Lady studio in the city. Batson played tack piano and sang in a ragged baritone, while Speleos blazed away on fuzzy guitar lines—a kind of East Coast Crazy Horse with neo-psychedelic edges. “It’s hippie rock with these guys who don’t really know how to sing,” says Parker. “The songs are not that bad, reminiscent of the Band but with darker themes—nothing like ‘Rag Mama Rag.’”

The Mike Jeffery–managed Holy Moses, whose first and only album was released on RCA in 1971

“The Sad Café” was Batson’s snapshot of the Café Espresso, the closing “Bazaraza Bound” an intense epic. “Billy wrote some great tunes,” says Jeremy Wilber. “He was a strikingly handsome man with many qualities, except for one little defect, which was that he could not drink a thimble of whiskey without turning into the meanest, most insulting sonofabitch that ever walked the earth.” That might not have mattered had Mike Jeffery not lost his clout with the death of his most famous client. “When Hendrix died,” says Wilber, “Holy Moses was dropped like a stone.”

By the time that band had unraveled—Speleos sloping off with Great Speckled Bird, Parker joining Paul Butterfield—Woodstock was rife with homegrown groups. Like Holy Moses, Hungry Chuck only got to make one album, an eponymous 1972 release on Bearsville that leaned closer to countrified roots rock than Holy Moses!! did. Fresh from commitments to Great Speckled Bird, the group’s core members—Jim Colegrove, N. D. Smart II, and pianist/singer/writer Jeff Gutcheon—teamed up with Amos Garrett and added Ben Keith and trumpeter Peter Ecklund to the mix. Hungry Chuck might have been the Band had the Band really been “the New Sound of Country Rock,” as Time described them. “I signed them to Bearsville, and we made an album,” says Michael Friedman. “I thought it was terrific, but Albert didn’t embrace it. They put it out but didn’t promote it, didn’t put out any singles. So I was disillusioned at that point, and the guys were crestfallen because I could probably have got them a deal with a major label.” Though the Hungry Chuck album stiffed, the group’s members evolved into a kind of floating session unit at the Bearsville studio. “People like Colegrove and Garrett were great ad hoc session musicians,” says Jon Gershen, then assisting at the studio. “They were fast on the uptake and very tasteful.”

Hungry Chuck should have gone on to greater things and did start work on a second Bearsville album, but Garrett’s continued involvement was blocked once he’d been recruited for Butterfield’s Better Days. “Albert was shoving his weight around,” says Colegrove. “We had a disagreement at Michael Friedman’s apartment in the city, and it got pretty heated. Michael said to me, ‘You were offering to go out in the hall with him—I’m surprised he didn’t go out there with you.’ Because Albert was pretty pugnacious.” When Colegrove demanded to know why Bearsville hadn’t pushed Hungry Chuck harder, Grossman protested that the album had been “mixed like it was a folk record and not a rock and roll record.” Colegrove countered that “we did it in your studio with your engineers, so it must be your fault.” The longer he knew Grossman, the less he liked him: “He had a sly, sneaky side to him. He didn’t operate on the level, and he had this manipulative power he liked to use on people.”

From Hungry Chuck’s ashes came an even more ill-fated band. Jook was formed by Colegrove with Billy Mundi, guitarist David Wilcox, and pianist/guitarist/singer Joe Hutchinson. “They were real good, the favorite band in Woodstock during 1974 and 1975,” Amos Garrett said. “But for some reason they couldn’t get a recording contract.” Despite regular shows at the Espresso and the new Joyous Lake club, Jook demos made at Colegrove’s Artist Road house never led to anything. Perhaps their progress was blocked by the unseen hand of Albert Grossman.

JIM COLEGROVE PLAYED in an early incarnation of yet another local band. Formed in West Saugerties by John Hall—who’d played guitar in the late-sixties band Kangaroo with Teddy Speleos and N. D. Smart—Orleans was the result of Hall and his wife, JoHanna, getting out of the East Village after their apartment was burgled. After renting for a few months on Ohayo Mountain Road, the Halls used royalty payments from Janis Joplin’s “Half Moon” to make a down payment on a house just off Route 212. Soon they were ubiquitous on the Woodstock scene.

While the Halls wrote for other artists, John toured with Taj Mahal and with Karen Dalton.** “I met John through Harvey Brooks,” says John Simon. “They’d both played on a Seals & Crofts album I produced, and then I got a call from Taj’s manager saying he wanted to put together this tuba band. Howard Johnson was going to assemble the horn section, and they wanted me to assemble the rhythm section. So I called John, and I asked Billy Rich to play bass and Greg Thomas to play drums.” The result was Mahal’s delightful live album The Real Thing, recorded at the Fillmore East in February 1971.††

As much as he loved Mahal and touring, Hall was keen to make his own mark. “He came home from playing with Karen in Europe,” JoHanna Hall told me in the kitchen of the house they bought together in December 1971. “He said, ‘I have to start a band.’” That winter, drummer Wells Kelly moved down to Woodstock from his native Ithaca, gigging with Hall and urging fellow Ithacan Larry Hoppen to join them. For several months Orleans played around town, switching instruments onstage as the Band had done. “They were doing Hendrix stuff and ‘Knock On Wood,’ different funky things,” says Jim Weider. “John’s guitar playing was amazing back then.”

“They played every weekend, alternating between Ithaca and Woodstock,” says JoHanna Hall, who as her husband’s cowriter was the group’s de facto fourth member. “John and Wells and I would travel back and forth in an old white station wagon.” With Jim Colegrove unable to commit long-term to the bass spot, Hoppen’s younger brother Lance joined after graduating high school that summer. Meanwhile Hall continued to work as a session guitarist at Bearsville, playing with Bonnie Raitt when she came to town to record Give It Up in June 1972.

“That summer was one of the coolest, most fun, and most creative and most sparking scenes I’ve ever been part of,” Raitt remembers. “It was such a hotbed of creativity and romance. To me at twenty-two, to come from Cambridge and hang out with people like John, it was like Paris in the twenties. I can’t say we got a lot of sleep. Jean-Luc Ponty had the daytime session, and we had midnight till ten a.m. So you can imagine what it was like. I did the whole record on NyQuil and Freihofer’s coffee. We would have breakfast at Deanie’s and crash, then wake up and have steak and go back into the studio. I probably saved myself from some pretty damaging partying, because we were sleeping when everybody else was revving up.”

“Taj Mahal introduced us to Bonnie in New York at the Bitter End,” says JoHanna Hall. “I loved her, and she was always the voice I was writing for in my mind.” Hall was at Bearsville the night Raitt sang the album’s closing track, “Love Has No Pride,” a bruising ballad of masochistic need that Libby Titus had cowritten with Eric Kaz about Emmett Grogan. “‘Love Has No Pride’ was what ‘I Can’t Make You Love Me’ has become for me,” says Raitt. “It was the ultimate heartbreak ballad at that point, and I meant every word of it. I had just been in the middle of a terrible breakup, and my heart was aching for this person to come back.”

By early 1973 Orleans had signed with ABC-Dunhill and were making their first album in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. In 1975 they hit big with the rerecorded “Dance with Me”—originally from the Orleans II album cut at Bearsville—and established a breezy soft-rock style that earned them a deal with David Geffen’s Asylum. Anathema to the hipper critics, the top 5 smash “Still the One”—with its creamy duel-lead guitar lines—made Orleans one of Woodstock’s major seventies success stories. “They were really the house band here in town,” says Stan Beinstein. “Wells Kelly was the heart and soul of it, the humor of that band.”

“We felt part of the scene,” says JoHanna Hall. “We loved Astral Weeks, but we tended to do more three-minute pop songs. What we were doing was very different—more urban—than, say, the Mud Acres group.” For JoHanna, being a woman in the Orleans setup was problematic, especially when the royalties began to roll in. “As a female on the scene, you were disregarded if you were not a player,” she says. “There was a lot of resentment towards me.” Drugs didn’t help the situation: “John was Mr. Clean,” says JoHanna, “but some of the others were doing cocaine.” In 1984, seven years after John Hall left the band, Wells Kelly died of his excesses in London. “He took a gig with Meat Loaf,” says Stan Beinstein. “He was stone drunk and just had too much fun. They found him in an alley.”

Another of Woodstock’s “house bands” were the similarly soft-rocking Fabulous Rhinestones, led by singer-guitarist Kal David, who’d moved to Woodstock from California in late 1970 and joined forces with Harvey Brooks and keyboard player Marty Gregg. Signed to Michael Lang’s Just Sunshine label, for which they made three albums between 1972 and 1975, the Rhinestones were—like Orleans—a Woodstock institution. “Their vibes were similar, and their harmonic sensibilities were similar,” says Stan Beinstein. On the cod-Latin groove of “What a Wonderful Thing We Have” the Rhinestones seemed to pick up where Brooks’s former band the Electric Flag had left off.

“There were a lot of musicians and bands in Woodstock that weren’t signed to Albert or Bearsville,” says Amos Garrett. “Bands like Orleans and the Rhinestones pretty much woodshedded on their own, made their own records, and stayed on their side of the mountain.” Yet the connections were there all the same: members of both Orleans and the Rhinestones fraternized with—and played on albums by—Grossman-associated artists like John Simon and Paul Butterfield.

An act hatched at Bearsville, Borderline was a trio conceived by Jim Rooney and Jon and David Gershen after Jim and Jon had worked together at Grossman’s studio. The Montgomeries having folded, Jon Gershen began working up songs with Rooney at the Cooper Lake home of his girlfriend, Barbara. A deal with Avalanche, a label distributed by United Artists, followed. “Obviously Jim was rooted in bluegrass and folk, which was not my thing,” says Gershen. “But in a way it was a good thing that I didn’t know about the whole Club 47 story, because I might have thought this wasn’t a guy I’d have enough in common with.”

Borderline’s Sweet Dreams and Quiet Desires (1973) was a rootsy mix of folk, country funk, and pining waltz-time ballads that featured several of the stellar sidemen who’d played with Bobby Charles: Ben Keith, Jim Colegrove, John Simon, Billy Mundi, David Sanborn, et al. Also smuggled into the sessions, under wry aliases, were the Band’s Richard Manuel (“Dick Handle”) and Garth Hudson (“Campo Malaqua”). “It didn’t seem such a stretch to say, ‘Let’s get Richard and Garth in,’” Jon Gershen says. “Richard got it right away, yet he kept saying things like, ‘Are you sure this is good enough?’” Kicking off with Rooney’s adapted traditional “Handsome Molly” and concluding with Gershen’s aching “As Long as It’s You and Me,” the album was another example of Woodstock’s proto-Americana sound. “I think it’s a pretty good document of the Woodstock sound at the time,” Rooney says. “It was this neat sound that the Band was the leading example of, but all these great players were around, and most of them were on the Borderline album.”

After United Artists failed to release their second album, Rooney decided he’d had enough of managing Albert Grossman’s studio.** In late 1973 he moved to Nashville, where he enjoyed a successful career as the producer of artists such as Nanci Griffith, John Prine, and Iris Dement. “I had an instinct that it was time for me to move on,” he says. “The local legend is Rip Van Winkle. I had the feeling that the Catskills is a very enchanting place, but you could wake up twenty years later and still not be getting anywhere.”

Another album featuring a star-studded cast of Woodstockers was the third by British import Jackie Lomax, who had followed in the footsteps of his mentor George Harrison and fallen in love with the town. Lomax’s Three (1972) was a blue-eyed rock and soul set graced by members of the Band and much of the horn section employed on Rock of Ages. “Jackie had a great band,” says Christopher Parker. “They played the Sled Hill, and it was really powerful solid English rock.” In Woodstock, Lomax took up with former dancer Norma Kessler, who numbered Jimi Hendrix and Kris Kristofferson among her former lovers and was, in Parker’s words, “kind of a mover and shaker on the scene.” Kessler’s eccentric cowgirl outfits so reminded Lomax of Little Annie Oakley that he renamed her Annie. The couple were arch-scenesters in Woodstock, though hardly ideal parents for her seven-year-old son, Terry, whose own father—cult fashion photographer Bob Richardson—was a schizophrenic drug abuser and periodic visitor to Woodstock with his young girlfriend, Anjelica Huston. “My mom left New York in 1970 and moved up to Woodstock,” Terry Richardson said in 1998, by which time he was himself a controversial photographer. “[It was] just to get away from the city and not have to deal with the system or fashion anymore. Be a hippie, grow out her armpit hair, get a job as a waitress in a health-food restaurant. She was like, ‘Enough of this fucking city.’”

As amusing as Richardson claims it was to be seven years old in Woodstock—“all the little kids would be running around at one o’clock in the morning . . . I remember making out with Maria Muldaur’s daughter Jenni”—the experience was hardly a formula for lasting emotional health. Lomax and Annie Richardson frequently abandoned Terry in order to go out partying. “I remember that I never had a fucking babysitter when I was a kid,” Terry said. “And we lived in this fucking house in the woods, which is very scary for a child.”

THE WORLD OF Woodstock’s most feted rock group wasn’t a lot less dysfunctional than Terry Richardson’s childhood. The year 1972 was a lost one in the life of the Band. All five members went their separate ways. Rick and Grace Danko divorced. Garth Hudson worked on his Glenford house. Levon Helm detoxed from heroin at his parents’ home in Arkansas before spending a semester at the Berklee School of Music in Massachusetts. “That winter was great,” Libby Titus told me. “Levon was the greatest father, couldn’t wait for Amy to wake up in the morning. He even read some books.”

Robbie and Dominique Robertson, weary of Woodstock’s entrenched self-destructiveness, moved for a period to her hometown of Montreal. Dominique told Rolling Stone’s Greil Marcus that Woodstock was “everything people ought to want, and I hate it”—that there was nothing there but, in Marcus’s words, “dope, music, and beauty.” Perhaps overly influenced by the Robertsons’ disenchantment, Marcus—whose chapter on the Band in his groundbreaking Mystery Train (1975) did much to enshrine the (mostly) Canadians in the pantheon of American music—wrote that Woodstock felt “like a private club, inhabited by musicians, dope dealers, artists, hangers-on. . . . It seemed like a closed, smug, selfish place.”

As for Richard Manuel, he pretty much did nothing but drink and crash cars, usually in the company of his new crony Mason Hoffenberg. “Mason was still caught up in the whirlwind of the sixties,” recalls Robbie Dupree. “He was cloistered in a real small world, and he lived with Richard, which was something that was not even imaginable.” When Playboy’s Sam Merrill visited the Manuel-Hoffenberg lair off the Wittenberg Road, he found two chronic alcoholics and a house strewn with dog feces. Hoffenberg had kicked methadone but was penniless and loudly self-piteous. Manuel, he said, was “really fucked up. . . . I was in better shape before I moved in with him, and the idea was that I was supposed to help pull him out of the thing he’s in.” The latter appears to have been Albert Grossman’s bright notion, but then Grossman’s track record with junkies was hardly stellar. Hoffenberg further informed Playboy’s readers that it was his role “to head off all the juvenile dope dealers up here who hang around rock stars”; instead he and Manuel “sit around watching The Dating Game, slurping down the juice, laughing our asses off, then having insomnia, waking up at dawn with every weird terror and anxiety you can imagine.”

Jane Manuel had kicked her husband out that summer. “He didn’t have the coping skills to survive,” she told me in 1991. “People thought it was amusing to watch this guy drowning.” With no Band commitments to give him either structure or simple raison d’être, Manuel was disintegrating. When Bob Dylan came by to say hello, he made a swift about-face after stepping in dog shit.

To fulfill their contractual obligations to Capitol, the Band reconvened at Bearsville studios in the spring of 1973. This time there was no new material in the can: Robertson had been laboring on an ambitious symphonic piece called Works but had nothing tailor-made for the Band’s voices. Instead they did what many of rock’s sated stars did in the early seventies: they made a covers album. Moondog Matinee wasn’t terrible, but its primary purpose was to tread water while Robertson figured out what to do next. That turned out—after the group’s summer appearance at the huge Watkins Glen festival**—to be a reunion with none other than Bob Dylan, who came to Woodstock that summer to discuss plans for a new album and tour. Dylan was impressed by the scale of Watkins Glen and felt a renewed zeal for live performance. The first rehearsals for what became the mega-hyped Tour ’74 took place in Woodstock in the early fall, by which time Robertson had persuaded his bandmates to move with him to Los Angeles. “My thought was, ‘Let’s get out of Woodstock; we’ve burned down these woods,’” he told me. “The idea of being by the ocean—it all sounded good. L.A. was a decadent place, but Woodstock had become that too. Over the years a lot of undesirables had come up there.”

Could there have been a more pointed rejection of Woodstock than the Band’s relocation to Malibu in October? To leave the woods and mountains of the Catskills for glitzy oceanfront California seemed almost like a betrayal. “It was effectively an act of leaving Albert,” says Jonathan Taplin, who accompanied them. “Occasionally Sally would come through California on her way to Mexico or wherever she was traveling. But Woodstock was really not on our radar anymore.” Robertson had claimed the Band still had “managerial ties” to Grossman, adding rather disingenuously, “I don’t know about Dylan. . . . They may have something going, but I don’t know what it is.” The truth was that Robertson—like Dylan himself—was busy being seduced by David Geffen, who’d lured Dylan away from Columbia and was keen to add the Band to his trophy cabinet. In the end, the group was forced to pay $625,000 to get out of its management contract with Grossman.††

Recorded on the hop between rehearsals for Tour ’74, Dylan’s Planet Waves was no masterpiece but was given unfairly short shrift by critics. “On a Night Like This” galloped along nicely, and “Tough Mama” was satisfyingly funky. “Forever Young” was a more than credible hymn to childhood innocence, while “Dirge”—like other songs hinting at painful cracks in Dylan’s marriage—may be the most tortured vocal he ever put on tape. As for the sound of Tour ’74, heard on the double album Before the Flood, Dylan’s own dismissal of it as “an emotionless trip” has rather sealed its fate. Pampered and coked-out the six men may have been, but onstage they cooked up a din that Ralph J. Gleason—the éminence grise of Rolling Stone—rightly described as “pulsing, cracking, shaking,” driven by Levon Helm’s charging grooves and Rick Danko’s stubby, undulating bass lines. “The most significant thing about the ’74 tour to me was proving that we hadn’t been crazy,” said Robertson. “It was not incredibly different from what we’d done with Bob before. It was just this kind of dynamics—it got loud and it got soft. We’d come way down when the singing came in, and when the solos started we’d go screaming off into the skies.”

That’s a fair description of Before the Flood’s “All Along the Watchtower,” one of the most intense pieces of live rock ever recorded and almost the equal of the Hendrix version. Perhaps power was what Dylan needed after drifting for the better part of eight years. Yet old friends found it as bludgeoning as Dylan himself did. “I found the show powerful in a certain way,” Happy Traum noted after seeing one of the three Madison Square Garden shows. “Maybe it was anger that I felt, which is very powerful, but maybe it was a lack of gentleness.” Mimi Fariña, who saw the show in Oakland, heard “a branch of that old nastiness coming through, by the intonation of his voice.”

“The tour was very lavish,” Libby Titus recalled. “It was lots of dope and lots of girls. Occasionally the wives and girlfriends were brought in for shows, but it was all so sad and pathetic.” After the L.A. wrap party for the women and children, the tour was finally over. “Bill Graham had set aside a room for the offspring of all these lunatics,” Titus remembered, “for the wives who’d been cheated on and the kids who were destined to be scarred.” Dylan, ever restless and never one for commitments that limited him, did not look back.

The Band’s exodus from Woodstock marked the close of a chapter in the town’s musical history. Grossman was still there, and Bearsville was still busy, but the lo-fi, backwoods spirit of Big Pink had gone. “The last time I went back was after I met Jim Rooney in New York,” Amos Garrett said in July 1975. “We decided to go up and see how many old friends we could round up. We arrived on a Saturday night, but we couldn’t find a soul that we knew. It felt horribly like the end of an era.”

![]()

* Along with Wilber himself, Bang! can be seen on YouTube in an ABC-News clip about the Sled Hill Café, shortly before it closed in August 1971.

* One of the Halls’ songs, the Tymes’ “Ms. Grace,” topped the UK singles chart in January 1975.

† Hall also played on Simon’s Warner Brothers solo debut, 1970’s John Simon’s Album, recorded with an all-star cast that included Band members and sat somewhere on the piano-man/songwriter spectrum between David Ackles and Van Dyke Parks. Journey, Simon’s second (and rather less expensive) Warners album, appeared in 1972 and included both the instrumental “The ‘Real’ Woodstock Rag” and opening track “Livin’ in a Land o’ Sunshine,” a ten-minute epic about a Catskills summer that featured Dave Holland on bass and David Sanborn on sax.

* Borderline’s The Second Album was finally released by Capitol in Japan in 2001, and then by Real Gone Music/Razor & Tie in 2013.

* For an amusing account of an apoplectic Albert Grossman, see Rock Scully’s memory (in Living with the Dead) of him threatening Grateful Dead tour manager Sam Cutler at New Jersey’s Roosevelt Stadium just after Watkins Glen. “You cocksucking little limey sonofabitch,” Scullly claims Grossman yelled. “Your mother fucks sailors in a Buick!” The reason for Grossman’s rage? The Dead were being paid more than the Band.

† Geffen claimed he’d made a $10,000 bet with Grossman that he could get an album out of the impossible Bobby Neuwirth. For the full chaotic story, see Aronowitz, “A Movie for David Geffen” in Bob Dylan and the Beatles, 339–388.