TODD RUNDGREN WAS always out of step with rock’s prevailing trends. While everyone else in his peer group was doing drugs, he refused them. When they stopped doing LSD, he started tripping on mescalin and mushrooms. For him it was a badge of honor to be different.

More than anything, Rundgren liked to challenge his own internal limitations. After 1972’s Something / Anything? produced a second top 20 hit, the gorgeous “I Saw the Light,” he raced ahead of himself and began constructing his very own sonic laboratory, Secret Sound, in keyboard player Moogy Klingman’s New York loft on West Twenty-Fourth Street. There he set to work on the extraordinary A Wizard, a True Star, a stunning roller-coaster ride of genre mutations that to this day sounds more bravely futuristic than any supposedly cutting-edge electronica made in the twenty-first century. Where Something / Anything? was full of winsome micro-ballads and boy-in-his-bedroom doodles, Wizard was Todd going into full-on prog-psych overdrive.

“Psychedelics brought me to an awareness of myself that I’d had no comprehension of previously,” Rundgren told me of his first trips. “I began to see my ego elements as weird, goofy, aberrational appendages.” Though he never entirely abandoned the pop-ballad mode of his work to date, the Secret Sound sessions propelled him into a new realm of experimentation. “I had the idea that a synthesizer was supposed to sound like a synthesizer, instead of sounding like strings or horns,” he says. Along with the electronics and hallucinogenics came an immersion in mystical literature that supported his radical new ideas. “Todd started seeking,” says Bebe Buell. “He was asking a lot of questions.”

At Bearsville, Rundgren’s new path was greeted with mild consternation. For Albert Grossman, the label’s resident genius was straying ever further from the blueprint of Dylan, the Band, and Butterfield. Not that Rundgren gave much of a damn about that. “Todd just wanted Albert to make everything easy for him so he could be creative,” says Paul Fishkin, himself exasperated by Rundgren’s willful disregard for pop pragmatism. “He was off on his psychedelic adventure. And then a year later ‘Hello It’s Me’ becomes a hit, at which point we’re up against Todd in a completely different mind space. With five more potential hits on Something, he says, ‘No fucking way am I releasing anything else off that album.’” The climax of Rundgren’s defiance came in December with a kamikaze performance of “Hello It’s Me” on the TV show Midnight Special, on which he was dolled up like a glam-rock drag queen. “He had iron fucking balls, that I will say,” Fishkin laughs. “This is his chance to be Elton John and the Beatles, and he goes on TV with his eyes painted as multicolored teardrops.”

“Todd wouldn’t take any advice,” confirms Michael Friedman. “And the bottom line was that the public didn’t buy it. He wasn’t Stevie Wonder, another guy who could do it all but knew how to make commercial records.” Equally frustrated was young Marc Nathan, an ardent Rundgren fan who’d dropped out of New York University in 1972 to work as a Bearsville promoter. “Todd’s willingness to self-sabotage his pop career was tough,” Nathan recalled. “I don’t think I ever believed in anybody more than I believed in him, and boy did he become a tough sell at radio.”

As he had with Dylan, Grossman indulged Rundgren and trusted in his talents. Besides, he was making big money out of his prodigy’s production work. “I don’t think Albert kept that kind of distinction between star producer and star artist client,” Rundgren told Paul Myers. “I was always problematic that way and it probably would have been worse for a different kind of manager than Albert, who was used to dealing with people who could be very self-directed, temperamental or mercurial.” In the summer of 1973, Grossman vowed to make Rundgren the best-paid producer in the world and then delivered on the promise. For Grand Funk Railroad’s We’re an American Band he secured him an unheard-of advance of $50,000. “That was definitely the record that got us out of our East Thirteenth Street apartment,” says Bebe Buell, who found a three-story townhouse on Horatio Street. Soon she was dragging her reluctant beau around town to meet the right scenesters and tastemakers. On her urging he agreed to see a shambolic glam-rock band called the New York Dolls, deeming them a joke but producing their debut album anyway.

Not content with expanding the Wizard palette on early 1974’s equally diverse and thrilling Todd, Rundgren was keen to start a new band as a side project. “Everybody expected him to continue in the realm of Something / Anything?,” says Buell. “So when he dropped the Utopia bomb, it really caused a lot of unhappiness within the Bearsville hierarchy.” Sally Grossman said that the group lost not only her but “hundreds of thousands of people,” adding that all they did was “drag Todd down, in my candid opinion.” Utopia was nothing short of Todd’s own prog-rock band, inspired by Yes and the Mahavishnu Orchestra and featuring both Moogy Klingman and keyboard player Jean-Yves Labat, an eccentric Frenchman as passionate about synthesizers as Rundgren was.

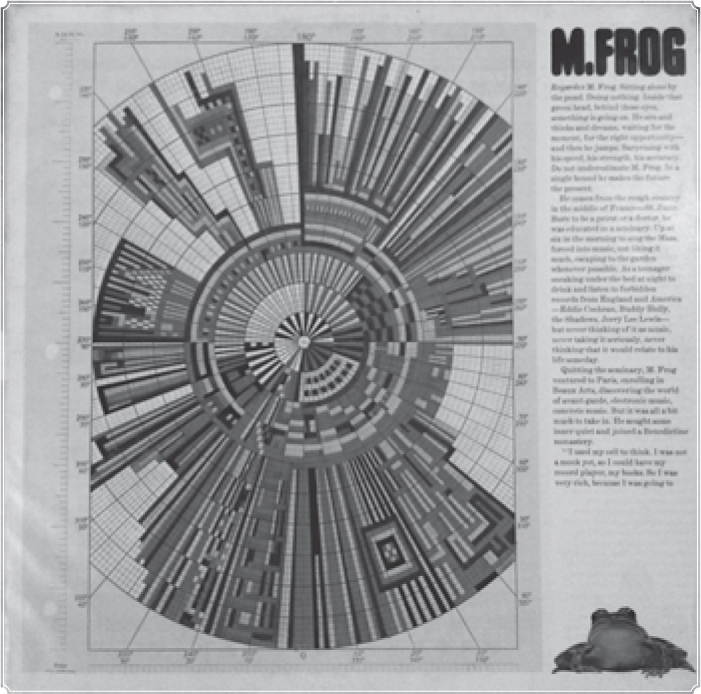

Labat had played with John Holbrook in the obscure Anglo-French group Baba Sholae, staying in touch after Holbrook landed a job in London with synth manufacturers EMS. Hyping Holbrook to Albert Grossman as “the new Glyn Johns,” Labat arranged for him to move to Woodstock. Falling in with the Grossman crowd at the Bear, where he had a job washing dishes, Labat even persuaded Grossman to bankroll a recording session in May 1973, agreeing to become “M. Frog” in the process.

Featuring an assortment of players from the Band and Paul Butterfield’s Better Days—as well as Rundgren, who mixed it at Secret Sound—M. Frog remains one of the stranger items in the early Bearsville catalogue. “It had nothing to do with the earthy Band aesthetic,” says Holbrook, who engineered and played guitar on it. “I don’t think anyone knew what the hell to make of Jean-Yves, but he somehow got people like Todd, Rick, and Garth to play on the record.” That is doubtless why Julian Cope—no fan of Woodstock earthiness—later championed M. Frog so breathlessly, describing the daft opening track “We Are Crazy” as sounding “like Jean-Pierre Massiera backing a spirited, three-chord/three-IQ band of heavy metal kids by blasting holes through their efforts with excruciating Synthi-A zappings, squiggles and explosions.” Whatever that exactly means.

“We Are Crazy” formed part of the live set on the first Utopia tour in the spring of 1973, when Rundgren and the band all sported multicolored hairstyles. Unfortunately the tour ground to a premature halt after an onstage fiasco that inspired one of the most painfully funny scenes in 1984’s This Is Spinal Tap. “We played one memorable show in Cleveland,” Rundgren says, “but we had a disastrous gig in Philadelphia, when this big elaborate intro built to a point of thunderous loudness, and there was no sound coming out of the guitar amps.” More humiliatingly, Jean-Yves Labat was trapped, like Derek Smalls, inside a Perspex geodesic dome that refused to open. “They all walked offstage, and Todd was extremely upset,” says Bebe Buell.**

Undeterred—and as stubborn as ever—Rundgren assembled a new lineup for 1974’s part-live Todd Rundgren’s Utopia, an album consisting of three epic prog pieces and the token four-minute pop-rocker “Freedom Fighters.” Through it all he was driven and restless, his mind working at five times the speed of everybody else’s. “Todd could be quite cutting and sarcastic,” says John Holbrook, who mixed the live sound for the Utopia tours. “The road crew had T-shirts made up that said, ‘Fear and Loathing in Utopia.’” For Buell it was painful to witness Rundgren’s withering putdowns. “He did not suffer fools gladly and had very little tolerance for anybody that didn’t match his intellect,” she says. “Patience was not his strongest virtue.”

Even Grossman was now getting short shrift from Rundgren. “There was a love-hate relationship between them,” says Mark McKenna. “Todd was Albert’s golden goose—at one point Albert bought him a Lotus for selling so many copies of ‘Hello It’s Me’—but then he wouldn’t lay any more eggs.” Things deteriorated so much between the two men that Grossman handed over managerial responsibilities to Susan Lee, Paul Fishkin’s assistant and the wife of local singer-songwriter Robert Lee. “Susan was the liaison between Albert and Todd,” says Buell. “I think she was in love with Todd, as were about seventy-five other women.” The twist in this dysfunctional tale was that Susan Lee had recently become Grossman’s mistress. “She’d been the manager of the Bear,” says Lucinda Hoyt. “That was kind of their relationship, but she was always inveigling her way into Albert’s business deals.”

Lee offered Grossman consolation of a sort for his wife’s persistent absences. “I never understood the marriage anyway,” says John Storyk, who was busy on designs for Grossman’s Bearsville theatre. “Sally was never there. For the longest time I didn’t even know they were married.” Grossman moved Lee into the Striebel house, the first time he had ever done such a thing. Linda Wortman, rehired by Grossman to run his publishing arm in New York, was no fan of Lee’s. “She didn’t do anyone any favors, and she certainly didn’t do Albert any,” she says. “I think she screwed around with his head, not only with his body.” Lee ceased managing Rundgren after a screaming fight between her and Bebe Buell at Mink Hollow. “Susan had a hammer, and Bebe had a pair of scissors,” says Kasim Sulton, Utopia’s new bass player. “Todd was in the middle saying, ‘Everybody please just calm down!’”

It was Lee who urged Rundgren to invest some of his newfound wealth in a property upstate. Initially he was against the idea: despite the time he’d spent in Woodstock, he did not wish to be part of Grossman’s cabal up there. “I thought it was kind of a cop-out moving to Bearsville, and I wanted to keep my New York City edge,” he says. “But I was making so much money as a producer and spending so little of it that finally Susan said to me, ‘You’re just gonna have to buy a house, or else the IRS will take your money away.’” In the summer of 1975, with the mystical Initiation in the record stores, Rundgren found a house northwest of Bearsville in Lake Hill. “Mink Hollow Road was very isolated, and I liked that,” he says. “Plus it had a barn where I could put my studio.” The reality of home ownership soon hit him, however: “When I moved in, it was completely unfurnished. It was just me and a sleeping bag. I had to go bed shopping, and I went through little antique shops throughout the Hudson Valley.”

Much to his own surprise, the urban wizard took to his new rural life. When Creem’s Robert Duncan visited Mink Hollow in the early fall, Rundgren—with a pair of dogs at his heels—was “squirreling about in the backyard visiting his saplings and his would-be-saplings, his corn, tomatoes and cauliflower, his eggplants.” He was even constructing an ornate garden on the property, becoming almost as obsessive a horticulturalist as Grossman. “Todd really worked hard to make that house beautiful,” says Buell, who posed for photographer Bob Gruen on the back of Rundgren’s lawnmower. “He built a Chinese water pond behind our house. We would go around in the woods looking for moss to attach to the rocks. He was constantly doing things to make the property Zen-like.” Rundgren told Duncan he was bored by rock and roll and by “the scene.” He was disappointed that “the generation that six years ago was into peace marches” was now “strung out on speed and fucked up. He says it was “time for me to leave the city—to make a full commitment to being by myself and learning about myself.”

“Todd was on a kind of spiritual quest at this point,” says Buell, who did her best to adjust to country life. “A lot of the songs he wrote were very introspective and extremely complex.” In 1976 Rundgren developed his most high-concept Utopia project yet, the Egyptian-themed opus Ra. Joining him in the latest lineup was Kasim Sulton, who—against Rundgren’s wishes—had been drafted into the group by Roger Powell and drummer John “Willie” Wilcox. “Todd begrudgingly accepted me but didn’t talk to me for a year and a half,” Sulton says. “The first day I went up to Woodstock, we drove from Manhattan to Mink Hollow in total silence.” A giant fan of Rundgren’s early pop-rock work, Sulton was thrown by the bombastic pretension of Ra. “When I joined the band, the New York scene was glam-rock and punk, and here I was in a prog-rock band,” he says. “When they told me I had to dress in a toga for the album cover, I cried.”

“I wasn’t being stubborn for the sake of stubbornness,” Rundgren says in his defense. “I considered Ra to be a serious relaunch of Utopia, and that was when we got as big as we ever got. But the changing style of music eventually eroded that whole audience. To me, punk was a particularly British phenomenon, albeit inspired by bands like the New York Dolls. In Britain it had a specific political component, and we didn’t have the same thing happening in America.”

If Grossman was hardly supportive of the stripped-down punk sound that had declared war on mid-seventies excess, he nonetheless couldn’t get his ponytailed head around Ra. “There was an electric winch that would slowly let Todd down to the stage,” says Paul Mozian, road manager on the Ra tour. “One night it starts coming down, and Tommy Edmonds, the engineer, lets him dangle there for a few seconds.”

It was all a long way from Dylan at the Gaslight or the Band at Big Pink. “Albert put up with Utopia,” says Kasim Sulton. “He did not care a whit about the group. But I don’t think he wanted Todd to leave, because at that point he didn’t have that big a stable of artists.”

With Bearsville Records at something of a crossroads, Grossman was too distracted to decide what to do about it. “I think he could see that the future for records was going to dwindle,” says Donn Pennebaker, who remained his friend. “But when you’re on a downward slope, nobody wants to help you.” Significantly, the main Bearsville office now moved from New York to Los Angeles, home of Warner Brothers. While Paul Fishkin and Susan Lee relocated to the Greif-Garris building on L.A.’s Beverly Boulevard, Grossman expanded the label’s offices in Bearsville itself. Assisting him there as his new head of A&R was the straight-talking Scotsman he’d known from London trips dating back a decade.

Ian “Ralf” Kimmet had fronted the glam-era UK band Jook—no relation to the Woodstock quartet of the same name—before giving up his pop-star dreams to run Bearsville’s UK office out of the Warners building in London. “Albert came to London with Susan Lee,” he remembers. “She showed me some recent Bearsville album covers, and I said, ‘They’re not very good, are they?’ I was a little punky at that point. She wasn’t very pleased.” In February 1978, Kimmet moved with his young family to Woodstock. Installed at Bearsville in the middle of winter, he did everything in his power to make the label more relevant. On the one hand he signed new-waveish acts such as the Johnny Average Band and Pam Windo & the Shades, along with soft-rock singer-songwriter Randy Vanwarmer. On the other he catered to Grossman’s vestigial taste for roots rock and R&B by reviving the flagging career of Paul Butterfield and putting legendary soul producer Willie Mitchell on retainer. “My first day at Bearsville, Albert divvied up everything,” Kimmet says. “It was like, ‘Butterfield’s yours, . . . you deal with the promo people at Burbank,’ and so on. So I started running the label while he was busy renovating the Bear and building the Little Bear. I’d constantly have to run around looking for him: ‘Albert! Albert!’”

“I don’t think Albert knew which way the wind was blowing,” says John Holbrook, by now the main engineer at Bearsville. “He came out of the fifties and sixties, when he had a grip on music, but now it was like, ‘What is this new wave bullshit?’ He signed Pam Windo & the Shades because it didn’t cost him anything, but he’d say, ‘Why are we working with this act?’ And Ian or Paul Fishkin would have to answer that question.” Bearsville even entered the hitherto uncharted waters of disco, signing both Hot Chocolate’s Tony Wilson and Norma Jean Wright, whose Chic-produced “Saturday” was a masterpiece of the Studio 54 era and an R&B hit in July 1978.

With Fishkin and Lee three thousand miles away, a schism of sorts opened up between Woodstock and L.A. Despite Vanwarmer giving Grossman the biggest hit single Bearsville ever had—1979’s maudlin earworm “Just When I Needed You Most”—Fishkin looked down on him. “I thought Randy was a lame signing,” he admits. “I was disconnected from it.” From the viewpoint of Kimmet—who’d specially remixed the track with Holbrook, overdubbing an autoharp part by John Sebastian**—“it became Albert and me here, and ‘What the hell’s happening in L.A.?’” Hardly unaware of Grossman’s flaws, Kimmet remained unflaggingly loyal to him. “Albert had great respect for Ian, who I always thought was a very brilliant person,” says Cindy Cashdollar, by then Bearsville’s receptionist. “He was almost like Albert’s muse. I think he was one of the few people Albert truly trusted.”

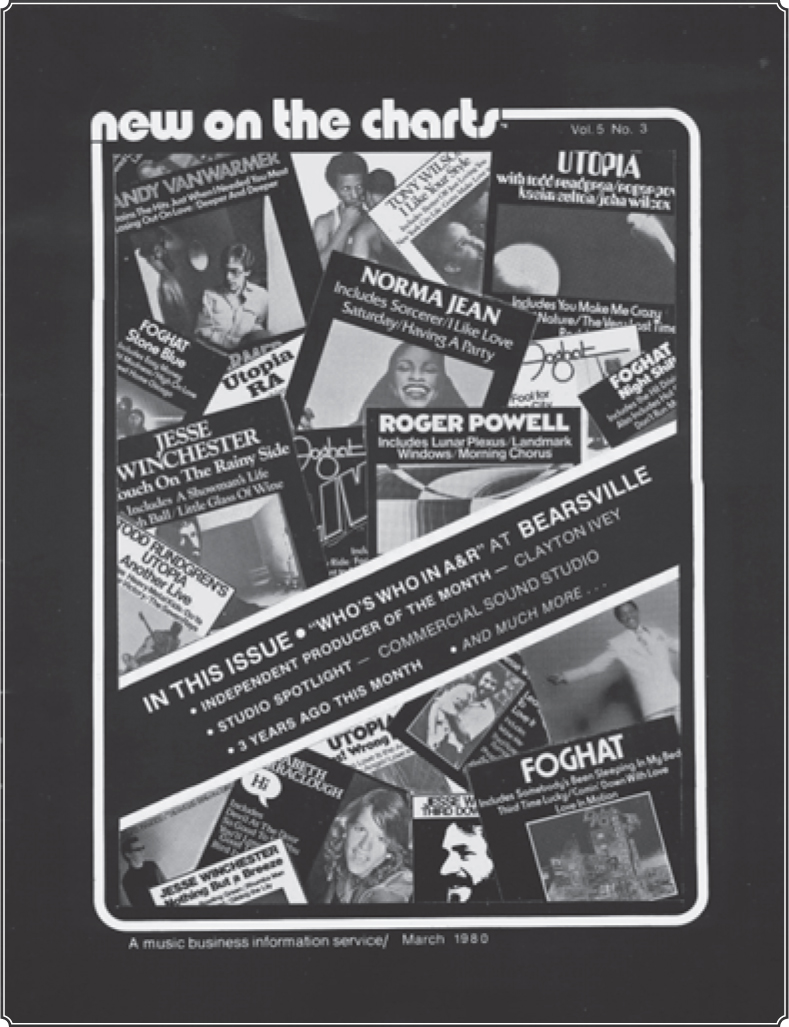

Billboard’s Bearsville spotlight, March 1980

Perhaps the most divisive Bearsville signing of the period was the bluesy singer-songwriter Elizabeth Barraclough, who happened to be Paul Butterfield’s new girlfriend. “Albert was very excited about her,” says Danny Goldberg, who briefly did PR work for Bearsville in this period. “He said she was a combination of Dylan and Janis, and insisted that I get high before listening to it.” Fishkin, on the other hand, was unimpressed. “Albert thought she was the next Dylan or Joni Mitchell, but she was a wreck,” he says. “I hated her and her music. I didn’t want money being wasted on his projects.” When Grossman flew to L.A. to ask Mo Ostin to commit to a proper budget for Barraclough—a decent songwriter if an unremarkable singer—he accused Fishkin of neglecting Bearsville acts in favor of his new girlfriend, Stevie Nicks. Fishkin tried to placate Grossman by saying he planned to sign Nicks to Bearsville as a solo artist. Grossman didn’t buy it, and additionally blamed Fishkin when Foghat—Bearsville’s most dependable cash cow—stopped selling. Secretly he was scared that Fishkin would abandon him. “Susan Lee said to me one day, ‘You have to understand, Albert is terrified of you leaving,’” Fishkin recalls.

In the end Fishkin did leave Bearsville. More painfully for Grossman it was to start a new label, Modern Records, with Danny Goldberg. “Albert was extremely pissed off and threatened legal action,” says Goldberg. “He looked at me as having taken Paul away from him.” It would be Modern, not Bearsville, that launched the solo career of Nicks. “She decided her boyfriend could run her career for her, and Albert sued their asses,” says Ian Kimmet. “Paul gave up everything for that.”

“Right before I left,” says Fishkin, “Albert wanted to leave Warner Brothers for RCA. I was so appalled that he would consider leaving Mo Ostin, because RCA was such a toilet in those days. So that was another thing that made me decide to leave. After he sued me, I went to David Geffen and told him the story. Before I’ve even finished it, David calls Mo and says, ‘Did you know Albert was going to fuck you?’ I was like, ‘Whoa!’ I got the best of Geffen in that moment. He was like an animal.” After the smoke cleared, Grossman bought Fishkin out for a million dollars. “He was really upset,” Fishkin says. “He never got over it, according to Susan. I would see him at conventions, but he was very cold towards me.”

Bearsville Records was certainly never the same after Fishkin’s departure and replacement by Howard Rosen as vice president and general manager. “Albert had Elizabeth Barraclough, Randy Vanwarmer, Jesse Winchester, and a few others,” says Kasim Sulton. “But it was hardly the stable of Bob Dylan and the Band and Janis Joplin.” Though he had worked hard to present a positive image to the industry—going so far as to host a special “Bearsville Picnic” filmed by the BBC for its rock show The Old Grey Whistle Test—Grossman’s eye was no longer on the prize.** “There was no money left,” says Ian Kimmet. “Albert was using it all for the buildings, so he wasn’t putting any money into promoting the records. The music wasn’t turning him on.”

“Albert Grossman was very standoffish up here,” says Ed Sanders, to whom Grossman had always been something of a capitalist ogre. “He had his little empire out there, and he kept pumping money into the studio so that big artists would come up to record.”

None came bigger than the Rolling Stones, who in the late spring of 1978 booked the Turtle Creek barn to rehearse for their forthcoming American tour, simultaneously hiring Bearsville’s Studio B for their pal Peter Tosh to mix his new album Bush Doctor. Keith Richards had just been busted for heroin possession in Toronto when the Stones circus rolled into town in late May: he had to be carried up to a bedroom by one of the “executive nannies” Mick Jagger hired to mind him. Jagger himself was determined to get healthy ahead of the tour and was often sighted jogging on Bearsville’s back roads, tailed by a minder in a Jaguar. Richards did not jog, and played too loud into the bargain. “The first chord Keith played in the Barn, there were a hundred phone calls complaining,” says Ian Kimmet. “So we moved them into Studio A.”

Periodically the Glimmer Twins poked their heads into Tosh’s mixing session. “Keith came in with a big bottle of pharmaceutical coke and dumped a small mountain of it on the table,” says John Holbrook, who was engineering the session. ‘‘He said, ’Ere, that’ll keep you going.’ The Rastas weren’t too keen, though. They didn’t really approve.” One of the more unlikely guests on Bush Doctor was Happy Traum, who received a call from studio manager Griff McCree asking him to come in with his autoharp. Plied with lethally strong ganja, Traum “tried desperately to keep the room from spinning out of control” and to put out of his mind the fact that Mick Jagger was “slouching in a corner.” Tosh and his Rastafarian friends also disapproved of their food being prepared by local cook Linda Sheldon, in case she was having her period. “Jagger swings into the kitchen one day,” Sheldon remembers. “And he shouts, ‘Where’s this unclean woman I’ve heard so much about?’”

The biggest drama during the Stones’ week of rehearsals came when Richards realized his US visa was about to expire. “They had to move all the farm equipment out of this nearby field so a helicopter could land,” Ian Kimmet recalls. “Keith climbed aboard, and then they flew him to Paris on the Warners jet. Forty-eight hours later he was back. So that was all very exciting.”

Even more exciting for Utopia crew member Tommy Edmonds was being hired as Richards’s guitar tech. “When Tommy left, he was maybe a hundred and ninety pounds,” says Kasim Sulton. “When he came back, he was a hundred and twenty-five. I said, ‘Tommy, what happened?’ He just said, ‘Keith.’”

UTOPIA CONTINUED TO compete for Todd Rundgren’s attention as he juggled the band with his “solo” work. “There was a whole period where I continued to make Todd Rundgren records but only toured with Utopia,” he says. “So it became this double life where Utopia was the live thing and drew giant crowds. There was a split in the audience, but there was also a big overlap.” Kasim Sulton says he would have given his eye teeth to junk Ra’s bombastic “Hiroshima” in favor of power-pop songs like “Couldn’t I Just Tell You.”**

“Todd felt under duress,” says Bebe Buell. “I noticed his boyishness began to diminish. He toughened up and lost a lot of his sensitivity. He became an angry young man.” Some of that anger had to do with the affair Buell conducted with Aerosmith singer Steven Tyler—whose daughter by her, Liv, was born in July 1977—though Rundgren had himself been persistently unfaithful and had recently taken up with a striking Texan redhead named Karen “Bean” Darvin. “He never had a shortage of partners,” Buell says. “I was just trying to keep up.”

Money continued to pour into the Rundgren coffers, especially after he took a punt on former Rocky Horror Show star Meat Loaf and his songwriter accomplice Jim Steinman, who’d been turned down by every label (including Bearsville) before landing a deal with Epic subsidiary Cleveland International. “It was one of those circumstantial things,” says Rundgren, who assumed Meat Loaf’s music was meant to be a parody of Bruce Springsteen. “If any one of the elements was different, we wouldn’t even be talking about it. At no point did it look like any sort of slam-dunk commercial success.” Recorded partly at Bearsville and partly at Rundgren’s new Utopia Sound studio at Mink Hollow, Bat Out of Hell—ridiculous and overblown though it was—went on to sell over forty-three million copies. “It’s the record I have the fondest memories of, because I was pregnant with Liv,” says Bebe Buell. “I had a craving for doughnuts, but every morning I would look in the fridge, and they’d all be gone. Meat had eaten them.”

Meanwhile Utopia released the Armageddon-themed Oops Wrong Planet, which mixed proto-AOR (“The Martyr”) with delirious prog (“The Marriage of Heaven and Hell”) and heartfelt anthemics (“Love Is the Answer”). Not that Rundgren’s apocalyptic politics ever aligned with those of his peers. “Around 1978 I happened to be on a bus to New York with him and Bebe,” says JoHanna Hall, who was getting busy in the No Nukes movement. “I thought, ‘This is my chance!’ So I went over and pitched him about being part of No Nukes. And he said to me, ‘Nuclear waste? We’ll just shoot it into outer space!’”

The year 1978 brought the release of Hermit of Mink Hollow, a feast of Rundgren melodiousness that included three aching breakup songs about Buell. Ever diffident about the music his fans treasure the most, he now rather disavows the album. “A lot of people are hung up on Hermit,” he says. “While it has songs I still like to perform, I don’t have the same feeling about it as most of the fans who like to hear it performed.” By the time the album’s bittersweet “Can We Still Be Friends?” cracked the top 30 in July, Rundgren had in any case moved on to his new obsession: video. Using Bearsville’s Studio A as an audio-visual workshop, he monopolized the space where the Stones had rehearsed—and which John Holbrook and others were now keen to retool as a proper recording studio. (“We got so tired of being in the claustrophobic Studio B,” says Holbrook, who made his own tongue-in-cheek Bearsville albums as “Brian Briggs.” “Here they were in the middle of a forest, and they hadn’t even put a skylight or a window in.”) When Ian Kimmet asked if they could take over the big room, Grossman demurred. “I can’t move Todd out of there,” he protested. In the end he gave in, but at the cost of building a hugely expensive state-of-the-art facility for his sometime golden boy.

“Todd told me he wanted to build a video studio and needed me to manage it,” says Paul Mozian. “I started looking for spaces in Manhattan, but he said, ‘No, you’ve got it all wrong—I wanna be able to drive down my driveway and go to work.’ I said, ‘But it’s not going to be a commercial venture in Woodstock.’ He said, ‘We’ll figure something out.’” The next thing Mozian knew, Grossman was up and running with the Utopia video studio, just across from his restaurants. “Albert had stayed so far away from commercial pop music that I was so surprised to see his relationship with Todd go on for so long,” says Robbie Dupree. “But then Todd was really different from anyone. He had a whole planet around him—the women he was with, the studio, his video thing, the Utopia people. It was Todd World.”

Funded largely by royalties from Bat Out of Hell, Rundgren’s video studio was a classic case of his being too far ahead of the curve. Despite an early and lucrative commission from RCA—to create a synchronized film for Holst’s Planets as a vehicle for demonstrating their new SelectaVision CED player—the studio was soon hemorrhaging money. By 1982, when Rundgren’s Surrealist-inspired “Time Heals” was the second-ever video broadcast on MTV, the operation was causing serious friction between him and Grossman. “There are people who think Albert should have kept a tighter rein on Todd’s spending,” says Bebe Buell. “And Todd spent a lot of money on that place.” The following year, things got so ugly between the two men that Rundgren arrived at the studio one morning to find Grossman had super-glued the locks shut. “We were all paying attention to Todd’s career,” says Ian Kimmet. “And then he wasn’t paying his rent, and it got to fighting.” One night when he was onstage, Rundgren described life as a Bearsville act as being like “being tied up in a bag in a hotel room and having someone shove an electric curling iron up your ass, turning it on, and then walking out the door.”

Rundgren hardly helped his own cause: after Adventures in Utopia crept into the top 40 early in 1980, spawning the minor hit “Set Me Free,” his response was to follow it up with Deface the Music, an album of Beatles parodies. With uncannily bad timing, the album came out three months before the shooting of John Lennon by a deranged young man whose preferred target for assassination had been Rundgren himself. When Mark Chapman was arrested for the ex-Beatle’s murder, he was wearing a Hermit of Mink Hollow T-shirt.

Rundgren had other reasons for falling out of love with Woodstock. On August 13, 1980, four masked men broke into the Mink Hollow house, binding and gagging him and the pregnant Karen Darvin and then robbing them while whistling his songs. “It was a horrifying violation,” he told Paul Myers, “and it started to make us feel kind of creepy about living up there.” The entirely solo Healing (1981) was written as a therapeutic response to the trauma they had suffered. Rundgren remained at Mink Hollow, paying the bills by producing artists at Utopia Sound. For all the years that had passed since his arrogance rubbed the Band and Badfinger the wrong way, little had changed in his modus operandi. Even those visitors who loved the location were treated with veiled disdain by their host. “His people skills are like Hermann Goering’s,” said Andy Partridge, for whose band XTC Rundgren produced the brilliant Skylarking (1986). “I remember talking briefly to a couple of the Psychedelic Furs,” says John Holbrook. “They were like, ‘That fucking guy, we’re never going to work with him again.’ With Todd it was always like, ‘That sucks, let me do it.’” Utopia Sound clients would often climb the stairs to the studio’s control room to find their producer with his feet on the console reading a book. “I can read and listen to music at the same time,” Rundgren protests. “When you’re in the middle of a session where the band is dithering, you can make suggestions, or you can let the whole thing run its course.”

“Working with Todd wasn’t really great,” admits Jules Shear, whose 1983 album Watch Dog was recorded at Mink Hollow. “Producing probably wasn’t what he really wanted to do. We did the whole record in two and a half weeks, including the mixing. I kind of liked the way he worked. A lot of people seemed to feel slighted by it, but I didn’t.” Indeed, Shear was so taken with the Woodstock area that after the sessions he decided to stay there. “Todd was really nice to me,” he says. “He said, ‘Just stay in the house till you find a place.’”

By 1986, the writing was on the wall for Utopia. With the group playing to half-empty houses, Rundgren spent increasing amounts of time in the Bay Area, where the computing industry was evolving in leaps and bounds. After the vocal-only A Cappella was shelved by Bearsville in 1984, he decided enough was enough. “Albert connived that the album was not acceptable,” he says. “I’d worked really hard on it and thought I’d achieved as complete a concept as I’d ever visualized, and yet he refused to accept it. This went on for a year, and I was just freaking livid.” The last time Kasim Sulton saw Grossman was at the last meeting to discuss Utopia. Afterwards, when the band left Bearsville, Mo Ostin signed Rundgren to Warners—with Grossman retaining the publishing. “I settled for that,” says Rundgren. “It meant I didn’t have to deal with him any longer.”

Rundgren continued producing at Utopia Sound before making a permanent move to California and recording the R&B-infused Nearly Human. Sally Grossman loved the album and threw parties for him on its May 1989 release. “People were not interested,” she said a decade later. “And they’re still not interested. It’s like this complete perception problem. I mean, it gets scary when you can’t sell a hundred thousand records.”

“The fact that Todd did exactly what he wanted, and didn’t bend to trends, is admirable,” Patti Smith says in his defense. “He’s always had very revolutionary ideas. He’s not just rebellious; he actually has a very strong, articulate philosophy, and he backs it up with action.” Though he’s influenced a hundred acts from Prince to Hot Chip and Tame Impala, Todd Rundgren remains the cult hero’s cult hero: Albert Grossman’s last prodigal son and Woodstock’s last true star.

![]()

* Labat was eventually fired from Utopia for his general belligerence, to be replaced by the more sober and capable Roger Powell. In 1978 the “Frog” man cut the unreleased Froggy Goes a-Punkin at Rundgren’s Utopia Sound.

* Sebastian had moved to Woodstock after a period in California, buying a house with the royalties he earned from the theme song to the TV show Welcome Back, Kotter, a number 1 hit in the spring of 1976.

* Padding around the Bearsville complex in one of his classic buttonless Native American shirts, Grossman informed Whistle Test presenter Bob Harris that he preferred working with “more personal artists, even if what they do may not be really important in the historical sense.” The hour-long film, shot in the summer of 1977, featured live footage of Foghat, Elizabeth Barraclough, Utopia’s Ra tour, and even the reclusive Jesse Winchester. There were cameo appearances by John Sebastian, a sheepish-looking Paul Butterfield, and a visiting Mick Ronson—soon to move to Woodstock—as well as music from Levon Helm and a skeleton version of his new RCO All-Stars. Finally there was footage of Rundgren at work on primitive computer videos in his new Utopia Sound studio.

* When I saw Utopia in 1977, I clung not just to Rundgren’s early-seventies gems but to the heavenly songs (“Cliché,” “Love of the Common Man,” “The Verb ‘to Love’”) from the previous year’s Faithful.