ON A MILD fall night in 1998, Levon Helm sits in almost pitch darkness in “the Barn,” his home-cum-studio off Woodstock’s Plochmann Lane. He’s wirily thin and ashen-faced, very different from the grinning roustabout he was in the great days of the Band. His pupils look pinned, though the only drug he consumes in my company takes the form of a hash cookie. More shockingly, his voice is faint to the point of near inaudibility. I feel guilty asking him to talk at all.

A few months back, Helm was diagnosed with—of all the cruel things—cancer of the vocal cords. Subsequently he’s undergone twenty-eight brutal doses of radiotherapy. “I didn’t have to have any chemo,” he rasps. “They tell me they think they got it, and God, I pray they did.” Next to living and dying, he admits his biggest concern now is being able to sing again. “I never thought much about it, because Richard was always the Band’s lead singer,” he says. “But now that I can’t, fuck, I really want to!”

Helm talks with a deep appreciation of his adopted Northern hometown. “Woodstock has been very forgiving,” he says. “It’s a town full of good people. Without having any kind of regular scene except a couple of studios, it’s really good because there’s no commercialism, and it just makes it quieter. People aren’t apt to come bothering you. Every now and then somebody’ll pull in looking for Dylan, but that’s about it.”

“Levon has always sought out the locals more than the artistic types here,” Happy Traum tells me a few days later. “He used to have these Fourth of July barbecues, and there would be at least as many of the local plumbers and carpenters and stonemasons there as musicians and artists.” For Traum, Helm’s diagnosis has had only a positive impact on his mental attitude. “I’ve rarely seen him so gregarious and cheerful since he’s come through the other side,” he says. “He seems to have been given a new lease on life.”

One thing, though, hasn’t changed in Helm’s attitude, and that is his rage toward the Band’s former guitarist. “Robbie Robertson’s got people who’ll say he wrote everything,” he says, fixing me with a steely glare. “Those are the same people that are helping him spend the fucking money, but he knows it ain’t right, it ain’t fucking true . . . and it damn sure ain’t fair for him and Albert Grossman’s estate to spend all the Band’s money.” Some of his friends, aghast at his boycotting of the Band’s 1994 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, have urged him to get over his grievances. “Ronnie Hawkins told Levon he should bury the hatchet, and I kind of agree,” says Ian Kimmet. “But there’s a working-class part of me that digs it and says, ‘Good for him!’”

WHAT I DIDN’T quite grasp as I wandered around the Barn in October 1998—and when I visited him again the following January—was just how broke Helm was. He and his wife, Sandy, had, in fact, been declared bankrupt, and the Barn was in serious danger of being repossessed. Within a decade, though he was still in debt, almost everything had turned around. He had kept the cancer at bay and was even singing again. With the help of his new right-hand man Larry Campbell, he’d recorded the widely hailed comeback Dirt Farmer (2007), a Grammy-winning album of Americana—part Muddy Waters, part Dock Boggs—that made far more sense than anything he’d released previously as a solo artist.

More triumphantly still, he had turned the Barn into the live venue he’d always fantasized about. “Levon and I built houses at the same time,” says Garth Hudson. “He said to me, ‘We’ll have a show, and we’ll call it Uncle Remus, and we’ll have various groups and singers, and we’ll televise it.’” Stan Beinstein remembers Helm voicing a similar dream: “He told me he was going to set a stage up at the Getaway and have Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley come up to play. I thought, ‘A hundred and eighty people in the place, and these people are coming up here?’ And then I went to the Barn years later and thought, ‘Holy shit, he did it. In his own living room.’”

In 1991, when I visited the original RCO barn Helm had built in the mid-seventies, it was literally a smoldering ruin. A fire had recently gutted the place, though some locals thought he might have torched it himself to collect the insurance money. Rebuilt in the same spot and to the same specifications, by the summer of 2005 the Barn was home to a weekly Midnight Ramble hosted by Helm and featuring his daughter. “Amy being part of the band, as well as part of the family, really made it special,” says Mercury Rev’s Grasshopper. “Playing with her dad and helping him, it all came together.”

“I was always wary of being around my idols, and I’d heard Levon could be a little mercurial,” says trumpeter Steve Bernstein. “The first Ramble I played was in November 2004. I wrote some quick horn charts and said to [saxophonist] Erik Lawrence, ‘I don’t want this to sound like a wedding band.’ When Levon got on the drums, it was like the purest free improvisation ever.”

The Ramble owed almost everything to the crusading belief and commitment of Barbara O’Brien. Saddened by the deaths of Richard Manuel and Rick Danko—and distraught at the depressed state in which she found Helm in 2003—she set about making the drummer’s dreams come true. “I always felt I could straighten the Band out,” she says, sitting outside the Barn on a balmy fall afternoon. “I didn’t want to be their girlfriend; I just wanted to help them.” When I went to the Ramble in July 2009, it was immediately clear she had done just that. “She’s the first manager he’s ever had that you could call a manager,” said John Simon, who was himself performing that night. “She’s stable and not crazy, and the fact that Levon’s put his trust in her is a wonderful thing.”

As I sat with Helm’s band members in a ramshackle den off the Helmses’ homely kitchen, I noted framed pictures of former comrades on its walls. (Rick Danko and Richard Manuel were there; Robbie Robertson, predictably, was not.) Slouched on the sofa, raking his fingers across an acoustic guitar, was Larry Campbell. Wedged in a corner and almost obscured by a vast tuba was Howard Johnson. “Someone gimme an A?” requested Byron Isaacs, the dapper bassist who anchored the band’s sound—to which Johnson responded by producing a subatomic fart from his instrument. Laughter—from Isaacs and Steve Bernstein, and from Campbell and his Tennessee-born singer-guitarist wife, Teresa Williams—rippled across the room.

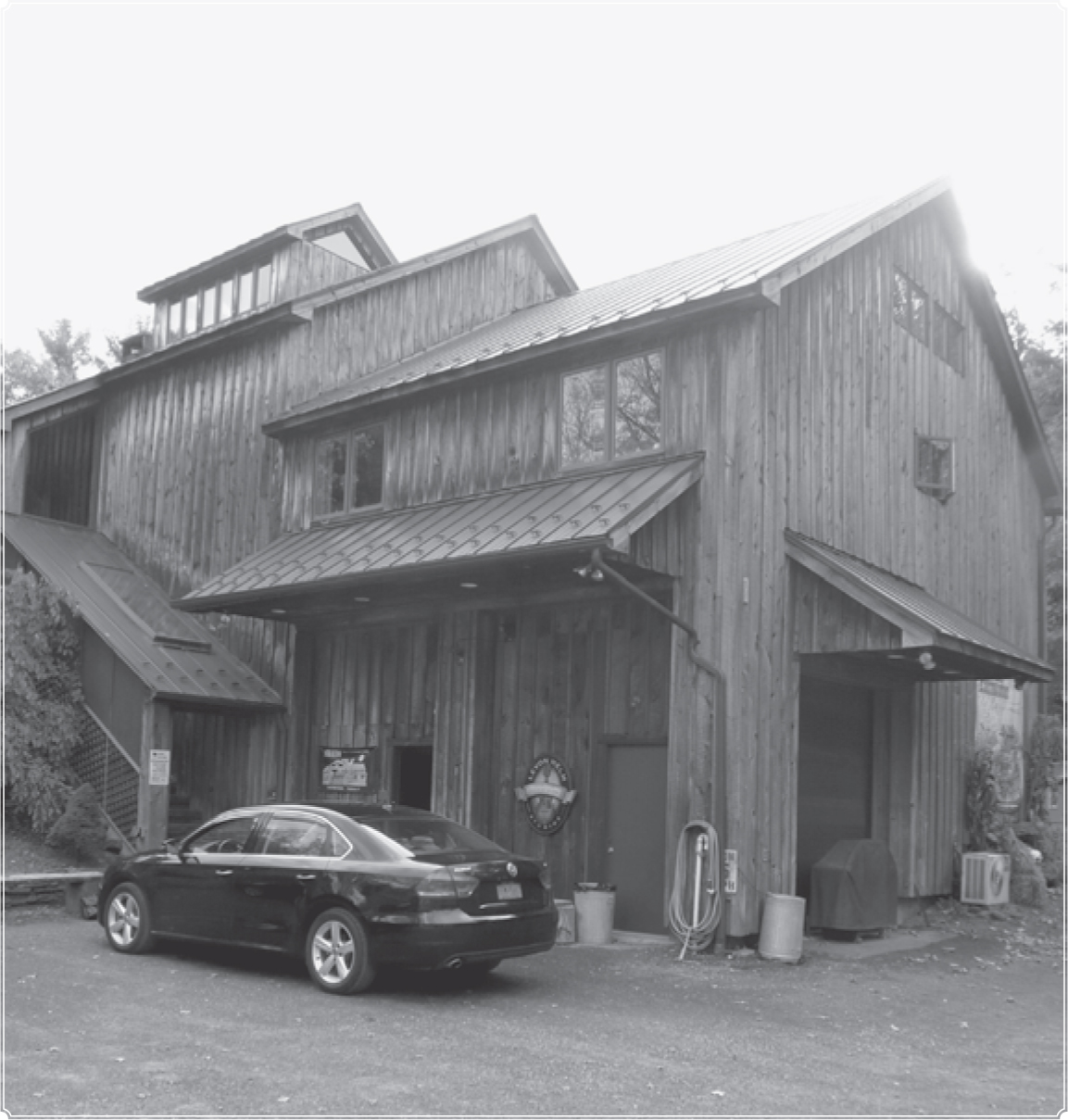

Levon’s barn, home of the Ramble on Plochmann Lane (Art Sperl)

Rumors had drifted around that Helm wouldn’t be singing at that night’s Ramble. Underlying them was the faint dread that his cancer had returned. “It’s only the second time this has happened,” he told me. “Before that we haven’t had to worry about it. What voice I’ve got, I’ve always been able just to push it on out there.” The Ramble was enormous fun anyway. After short sets by John Simon and octogenarian blues man Little Sammy Davis, Helm and band kicked off with “The Shape I’m In,” the first of six Band songs included in the show. Stick-thin and ghostly pale in a loose pink shirt, Helm was still—in Campbell’s stage announcement—“the greatest drummer in the world.” And that was true whether he was channeling the second-line spirit of New Orleans on Jelly Roll Morton’s “I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Sing” or supplying clipped country-soul rim shots for his daughter’s rendition of William Bell’s “Everybody Loves a Winner.” As he’d so often done with the Band, he switched periodically to mandolin—in this case for the country waltz “Did You Love Me at All.” If there was something a mite contrived about the way he had been positioned as a patron saint of Americana—O Levon Where Art Thou, anyone?—Helm himself was as genuine an article as American music could boast.

At that point, Larry Campbell had been playing the Rambles for four years, ever since quitting Bob Dylan’s road band. “Levon and I had a two-hour conversation about the similarity of our experiences with Bob,” he says. “At the end he said, ‘Well, whyn’t you come up to Woodstock, and let’s make some music together!’ So I came up and never looked back.” When Campbell moved back to town, Helm finally had himself a proper bandleader. “It sort of rounded out the rhythm section plus the extra voices we needed,” he said. “And then with Barbara coming in, that kind of took care of everything on the other side of the desk.”

That night, Helm talked again of Woodstock. “There’s something about it,” he said. “For me it’s part of the South. It’s one of the best towns I’ve ever known, and it still looks and acts the way it did when I first got here.”

“Levon personified the spirit of the place, musically and in his country manner,” Larry Campbell tells me today. “You could never get him to say a bad word about this town. From 1968 to the day he died, he said there was nowhere he’d rather be. He said, ‘Woodstock is the one place where you can just be who you are.’” For Steve Bernstein, Helm was “kind of the symbol of what Woodstock meant. . . . It was like he was one of us, not like some untouchable rich guy that got separated.”

Anyone who ever saw a Ramble will tell you what an intimate and organic experience it was. “Levon ended up doing exactly what he wanted to be doing, and he was right,” says Paul Fishkin. “Everything I ever revered about the music world and how it should be was manifest in the Ramble.” For Marshall Crenshaw, who guested at the Barn in November 2009, there was no scene in Noughties Woodstock before the Ramble. “It galvanized people,” he says. “I took my eight-year-old son, and he sat right behind the drum kit. At one point Levon turned around and gave him this great big grin. And then he handed him a set of drumsticks. He’s never gotten over that.”

Among the other luminaries to play the Ramble were Elvis Costello and Allen Toussaint; Ralph Stanley and Charlie Louvin; Gillian Welch and David Rawlings; the Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh and Bob Weir; Jackson Browne and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott; Bill Frissell and Billy Bob Thornton; Kris Kristofferson and Kinky Friedman—along with John Prine, Norah Jones, Hubert Sumlin, Taj Mahal, Mavis Staples, and far too many more to mention. Among those with a direct connection to Woodstock were Happy Traum, John Sebastian, Donald Fagen, Jesse Winchester, Maria Muldaur, Natalie Merchant, Cindy Cashdollar, and the Felice Brothers.

Garth Hudson, who guested at the Ramble “four or five times over the years,” says he felt an almost paternal pride in what Helm achieved at the Barn. Woodstock Times editor Brian Hollander shared in that pride. “There’s no Big Daddy like Albert in town anymore, but Levon enjoyed that role,” he says. “He enjoyed having a twelve-piece band coming up to his barn and getting a good payday.” At the turn of the decade, Barbara O’Brien began inviting younger acts—bands such as Drive-By Truckers and My Morning Jacket—to the Ramble. “I’d read the bios of Mumford & Sons and Dawes, and they always mentioned the Band,” she says. “They were getting that scruffy look, with the wrinkled white shirts and the vests and the hats. To see these kids in absolute awe of Levon was beautiful.”**

On March 31, 2012—with Los Lobos as his special guests—Helm played his last Ramble. The cancer had returned with a vengeance, and he was soon back in Memorial Sloan Kettering, the hospital which had saved his life. This time there was nothing they could do except make the end as comfortable as possible. Word got around to everyone who needed to know and wanted to say good-bye. Among them was Robbie Robertson, contacted by the woman now known—after her marriage to Donald Fagen—as Libby Titus-Fagen.

In 2005 I’d asked Robertson how pained he felt by the bad blood between him and the man who’d been like an elder sibling to him. “I do feel deep in my heart that my brotherhood with Levon is untouchable,” he’d replied. “I just wish him well and hope he doesn’t have to live a life of bitterness and anger. He was like my closest friend, so I just want the best for him and hope he finds a way to relieve himself of having to deal with everything through negativity.”

On the surface, therefore, it was moving to learn of Robertson’s visit to Memorial Sloan Kettering on April 15. “I sat with Levon for a good while, and thought of the incredible and beautiful times we had together,” he wrote on Facebook. Though Robertson did not claim he’d spoken with Helm, the wishful thinking of others turned the deathbed scene into a touching moment of reconciliation. “Amy told us she went in and said, ‘Dad, is it true you patched things up with Robbie?’” says Jonathan Donahue. “Levon said, ‘We didn’t patch up shit.’”

Yet Titus-Fagen, who sat outside the hospital room during Robertson’s visit, wrote this to me six days after Helm died: “The story is much more complex than the bloggers and the press understand. I can tell you that, for the years I was with Levon—from 1968 to 1974—they each shared a part of the other’s soul. One would start a sentence, pause, and the other would finish it. They had their own alphabet, their own clock, their own DNA, a Levon-Robbie double helix. When I called Robbie to say Levon was dying, he was stunned, shattered—he thought Levon had beaten the cancer.”

“Robbie flew to New York to say goodbye,” Titus-Fagen added in her email. “Amy, Donald and I were in the waiting room, and I don’t know what Robbie said to Levon for the long time he spent by his bedside. All I know is that there’s a side to this life-and-death song that no one has heard. Levon wouldn’t want this bitterness to ramble on any longer.”

OVER TWO THOUSAND Woodstockers paraded past Helm’s coffin at the Barn before his burial in the town’s Artist Cemetery, where everyone from Ralph Whitehead to Rick Danko lies in peace. Afterwards I remembered some words Danko had said to me in 1998: “Levon and I have known each other nearly forty years, and we’ve never once slapped one another. We’ve never come to blows. We’ve always maybe been smart enough to talk it out. And we’ve always protected one another.”

All three of the addicts in the Band are gone now, and it seems such a waste, not only of their exceptional talent but of their touching brotherhood. “I keep telling my son that those guys were no role models for how to live life,” says Marshall Crenshaw. “I say, ‘You can’t miss the fact that they’re all dead, and they’re all dead because they lived their lives in a fucked-up way. They were good people, but they were childlike in all the wrong ways.’”

Formerly known as Route 375

A year after Helm’s death, the New York State Legislature approved a resolution to name Route 375—the main artery connecting Woodstock to Kingston and the New York Thruway—Levon Helm Memorial Boulevard. At least one Woodstocker found this risible. “I don’t wish to denigrate the fame or name of Levon Helm and the Band,” Carl Van Wagenen, a police chief who frequently arrested them in their heyday, wrote to the Daily Freeman. “But . . . wouldn’t it have been wonderful if they had donated all the money they stuffed into their noses to more appropriate venues? Does having an alternate drug-fuelled lifestyle, interspersed with occasional bankruptcies, really qualify one to have a road named after him?”

When you’ve made some of the greatest American music of the past half century—and been the wild life and troubled soul of Woodstock, New York—then yes, Mr. Van Wagenen, it does.

![]()

* Drive-By Truckers, scions of Alabama, had included a harrowingly beautiful song about Rick Danko and Richard Manuel on their 2004 album The Dirty South. “Fifteen years ago we owned that road,” its author Jason Isbell had sung. “Now it’s rolling over us instead.”