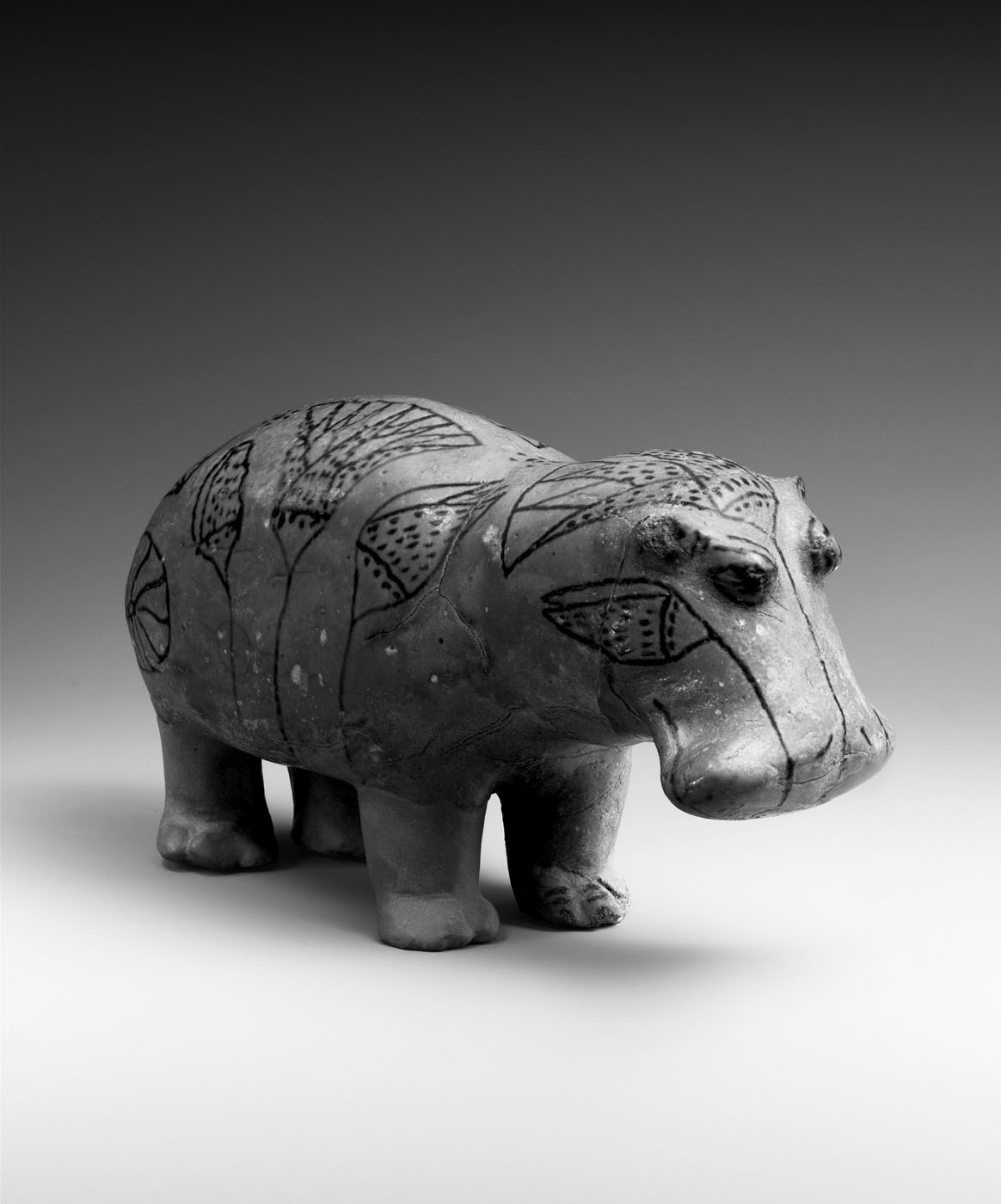

Faience hippopotamus with lotus flowers on its body. Three of its legs were broken off in antiquity.

Hunting a hippopotamus is not an activity that is recommended, not only for ethical and legal concerns, but also for practical reasons. They are extraordinarily large creatures, for a start, and aggressive when it comes to defending their young from predators or other hippopotami. The jaw of a hippopotamus can clamp shut in seconds, and although hippopotamus teeth are designed for a plant-based diet, they also have long, curved incisors that grow to a point. An aggrieved hippo can easily run down a human, or overturn a boat. So please, no hippo-hunting in real life – but a little hippo could come in handy for your ventures in magic.

Faience hippopotamus with lotus flowers on its body. Three of its legs were broken off in antiquity.

A hippo as little as the span of your hand, to be precise. Archaeologists have found shiny blue figures of hippopotami in a range of postures in Middle Kingdom and slightly later burials. These hippos all have two things in common. First, they are primarily made of faience, the glazed paste so tricky to produce that it was believed to have mysterious, magical qualities. These hippos were made from a closely guarded recipe, pressed into moulds and fired in a kiln to bring forth their blue shimmer. Often, a black, manganese-based glaze decoration was painted on before a piece went into the kiln; the hippos’ bodies are adorned with lotus leaves, buds, and blossoms, making it seem as though the animal has merged with the plants that grew in the riverine marshes that were its home.

As if that weren’t magical enough, these hippo figures have a second thing in common: each had a foot broken off or damaged when it was placed in the tomb. Some may even have been broken in two. This doesn’t fit our modern idea of how such beautifully made objects should look, and many museums or private collectors have replaced the missing foot to make the hippo appear intact. In ancient Egypt, however, these figures weren’t made to be looked at and admired. They were made to be used. The breakage is all that remains of the magic ritual that was their entire reason for being. Reduced to manageable size, and in their magic-imbued faience form, these hippopotami helped the priest-magician in charge of the burial control the destructive power of the animal and all it symbolized. Once the figure had been hobbled and tamed by magic words and actions, it may also have served the double purpose of protecting the tomb and the dead from harm. Not a decorative object, then, which is what these striking blue hippos have become in museum gift shops. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, you can buy hippo-patterned socks in honour of their famous figurine, known as William. At least you get to keep both of your feet.

We’ve already seen that ancient Egyptian ideas about the supernatural world allowed for ghosts and spirits that could move between this world and the next, and that the gods and goddesses they worshipped could take human as well as animal form, or some mixture of the two. The god Osiris always took human form, reflecting his role as a mythical king, while his brother Seth, his son Horus, and his sister-wife Isis all appear in different human and animal forms. So does the sun-god Ra (usually with a falcon’s head), who was accompanied on his daily journey across the sky and through the Duat by dozens of gods and demi-gods, each as weird and wonderful as the next. ‘Demi-god’ and ‘minor god’ serve as catch-all terms for supernatural beings that were not important enough to have huge temples built in their honour, but nonetheless played a key role in the world of the gods – and, therefore, in the world of magic and magicians.

This chapter looks at a panoply – a menagerie, even – of supernatural beings and their counterparts in the natural world. Human figures of different ages, genders, and body shapes were gleefully combined with parts of animals, birds, and reptiles of every imaginable variety. This wasn’t because ancient Egyptians worshipped ‘monsters’, as the Roman satirist Juvenal rather harshly put it. Instead, this bewildering diversity of humans, animals, and creatures in-between enabled Egyptian artists – and magicians – to harness the potential of an otherwise invisible world. But with so many deities and demi-gods to choose from, how did a magician know which creature to conjure, and which to avoid? The physical forms that gods take in art and magical objects can help us understand some of the connections between them, as well as giving us an important insight into the purpose of images in magical practices. Like the hippopotamus figures that had to have a foot knocked off, any image made to represent a powerful animal, a semi-divine spirit, or a full-blown god had the potential to channel the supernatural energy of what it represented, and its potential dangers thus constrained.

The ancient Egyptians believed that the supernatural was everywhere – and nowhere, since it could not be perceived by normal senses like vision. Instead, supernatural forces made themselves known through unusual natural phenomena, like thunderstorms; through dream-like visions that some humans received; or through the heightened perceptions that magicians acquired during a rite.

The Egyptian gods that are most familiar to us – Osiris, Isis, and their son Horus; Thoth, the god of writing and wisdom; Amun, the creator-god of ancient Thebes; the sun-god Ra and his daughters, Sekhmet, goddess of war and disease, and Hathor, goddess of love and beauty – make up only one part of the divine world of ancient Egypt. Many of these deities can be traced to very early written sources, like the Pyramid Texts, and all of them qualify as a netjer, the Egyptian word for a major god or goddess. These major deities had complex mythologies and were worshipped all over Egypt, although they often had a specific centre of worship that may reveal their local roots, such as Dendera for Hathor, Abydos for Osiris, or Heliopolis (now part of Cairo) for Ra.

In the visual arts, the major deities developed standard characteristics that make them easy to recognize once you know what to look for. Some take the shape of attractive humans, distinguished by the crowns or hieroglyphic symbols on their heads: Isis and Hathor balance the hieroglyphic writings of their names on top of their beautiful dark hair, while Amun sports a crown made of two tall feathers. Others have the head of an animal poised atop the shoulders of a human body: a falcon for Horus and Ra, a lioness for Sekhmet, and an ibis for Thoth. But gods and goddesses could change their forms, too, and be represented by an animal alone: Hathor as a cow, Thoth as a baboon or an ibis, and Isis as the kite, a common bird of prey. We shouldn’t assume that the ancient Egyptians imagined that their gods looked precisely like these figures. Instead, the beautiful bodies, human-animal composites, and animal avatars were ways to represent in physical form what only existed beyond the immediate physical limits of human experience.

In addition to all these major gods, the supernatural world was populated by myriad beings that could also take an even more astonishing, even bizarre, array of forms. This was in keeping with the way such beings functioned as adjuncts, or at times enemies, of the gods and as intermediaries between humans and the divine realm. Egyptologists have used several words to characterize these minor gods, since there is no single word in ancient Egyptian to categorize or describe them. The word ‘minor’ makes them sound unimportant, but they weren’t, especially in Egyptian magic. To take just two examples, the dwarf-bodied god Bes and the hippo-hybrid goddess Taweret were both gods associated with the protection of households, women, and children, and appear in many magic images and spells as a result (both are discussed in more detail in Chapter 6). Some of the less familiar gods called on in magic spells were of non-Egyptian origin, like the goddesses Astarte and Qudshu from ancient Babylonia, or the Canaanite god Samanu, who was called upon in New Kingdom spells to cure skin disorders and other physical complaints. Their foreign, exotic quality was part of these deities’ appeal, since magicians knew magic worked best the more mysterious it sounded.

Amulet depicting Horus as a young child, between his mother Isis (left) and her sister Nephthys (right).

Then there are the supernatural creatures that Egyptologists have variously referred to as demons or genies, or more generally as spirits, other than the mwtw and akhu whom we met in the last chapter. Demon – from the ancient Greek daemon, meaning a lesser deity – has come to have a negative connotation in English, and is often used to describe the harmful spirits encountered in magical texts. A demon was any force that might cause something bad to happen to you, and the purpose of many magic spells and amulets was to protect you from these manifestations of the great unknown. Such dangerous creatures were associated with ponds, canals, and wells, perhaps reflecting a fear of falling into deep water, or the unpleasant smell of standing water. Unnamed groups of demons also appear in magic spells, where they might be likened to the enemies who attack the sun-god in his solar boat. Some demons were messengers from the goddess Sekhmet, who brought disease, warfare, and strife into the world.

People in ancient Egypt reckoned time like we do, by the changing seasons and days of the month. There were three seasons in a year, each lasting four months: Akhet, when the Nile flood progressed from south to north (roughly July to October); Peret, when the flood receded and farmers could plant crops (November to February); and Shemu, the harvest (March to June). Each month had thirty days, with five extra days added between the end of Shemu and the beginning of Akhet, when the world waited for the unpredictable flood season to start and the new year to begin. These were days of celebration but also of danger, as demons ran amok. Egyptologists refer to these as the intercalary or epagomenal days, because they fall between the last and first calendrical months. Let’s call them demon days, because they required special protection against Sekhmet’s sinister henchmen. Magicians made special amulets out of linen or papyrus for people to wear during those trying times, surviving examples of which correspond to the spells and instructions known from magical handbooks. To make the demon-day amulets, the magician drew a series of gods in a row while reciting the spell, and the client wore it around his or her neck by means of twisted cords at either end. Some amulets have twelve figures drawn on them, corresponding to the twelve demons that Sekhmet was said to unleash, while others have five, clearly identifiable as Osiris, Isis, Seth, their sister Nephthys, and Horus. Each of these gods was said to have been born on one of the five demon days. Risky times brought some hope with them as well.

Papyrus amulet to be rolled up and worn during the ‘demon days’ at the end of the year.

Demons, demi-gods, major gods: whatever we call them and however we categorize them, there’s no question that animals both real and imagined were a vital part of magical practice in ancient Egypt. In fact, images of animals offer some of the earliest clues to the supernatural world of the Egyptians, long before the standard depictions of divinities emerged in visual imagery and hieroglyphic writing. On an intricately carved stone palette dating to the Predynastic era (c. 3200 BCE), a pair of lion-like animals with long, snake-like necks protectively surrounds a circular depression on one side of the object. Palettes like this are oversized versions of smaller, handheld palettes, where such depressions were used to grind the pigment painted onto participants in a ritual – perhaps a priest-magician, a ruler, a statue, or all three. The otherworldly animals, conjured out of the artist’s imagination, reflect the heightened sense of reality that such ritual performances created.

With the development of a larger, more centralized state and the invention of writing that accompanied it, ancient Egyptians drew closely on their observations of the natural world to depict the divine one in art, including hieroglyphic signs. The animal world offered examples of behaviour that invited cosmic explanations, especially where an animal’s actions seemed unusual (burying its eggs in dung, like a scarab-beetle) or miraculous (a bird in flight). From the most skilled, and secret, depictions that artists created on the walls of royal tombs, to the objects that magicians used in protective rites, animals were everywhere. Hippos, lions, jackals, all kinds of snakes, some remarkable reptiles, and a bewildering number of birds: you didn’t need an actual zoo to perform Egyptian magic. But a small menagerie came in handy – or at least, some familiarity with the kinds of animals a magician might need to know and the powers they might help him channel.

The ‘Two-Dog Palette’, a Predynastic example of both real and fantastic animals in art.

Limestone stela of the craftsman Aa-pehty praying to the god Seth, from Deir el-Medina.

The faience hippopotamus figures placed in Middle Kingdom burials still count as quadrupeds, even minus a foot. The hippo was feared in ancient times for the threat it posed to people working on or near the all-important marshes of the Nile. Its habit of moving between land and water, and cooling itself off with marshy, muddy baths, may have echoed Egyptian ideas about creation, many of which attributed primordial, life-giving powers to Nile water and Nile-drenched mud. But the hippo’s dangerous side also encouraged its association with Seth, the brother (and murderer) of Osiris and the god blamed for natural disruptions like thunderstorms and earthquakes. As a symbol of such danger and disruption, the hippopotamus appears in many contexts as a hunted, wounded animal, because a conquered hippopotamus symbolized triumph over the forces of disorder – exactly the kind of metaphor a magician might want to call on in rites that aimed to right a wrong, heal the sick, or avert disaster. Objects made of hippopotamus ivory had special magical potency, including wands that were used for health and protection, especially during childbirth and the care of small children (for which see Chapter 6).

As a god of disorder on an almost inconceivable scale, threatening no less than the destruction of the natural order itself, it was fitting that Seth also had as his symbol an animal that was itself inconceivable. The ‘Seth animal’ (finally, Egyptology gives us a sensible term) was a four-legged creature with a down-turned snout, long ears with squared-off ends, and a tail that sometimes took the form of an arrow, as if pinning this weird creature down to stop it from causing havoc. The beast wasn’t all bad, though: in the Delta during the New Kingdom, Seth also had a thriving cult that must have brought out his better side. He is honoured in the names of two 19th Dynasty kings, Sety I (r. c. 1323–1279 BCE) and Sety II (r. c. 1200–1194 BCE), whose family roots were in the region. Nevertheless, most magic spells that mention Seth were trying to curtail his negative influence.

The desert edges of the Nile valley were home to other wild animals whose ambiguous qualities – simultaneously feared and admired – made them ripe for magical interpretation, too. The jackal, for example, was identified with two gods who look almost the same in Egyptian art: Anubis, the jackal-headed god responsible for embalming and wrapping the corpse of Osiris, and Wepwawet, whose name means something like ‘opener of the ways’ or ‘route-finder’, making him a sort of sniffer dog to the supernatural realm. Jackals towed the sun-god’s boat through the sky, their tails sometimes represented as rearing cobras. A jackal stretched out alert on top of a chest was the hieroglyphic sign for mastering secrecy, the vital skill that priest-magicians needed to perform effective rituals. It read hery-seshta, ‘master of secrets’, as written on the lid of the box in which the Ramesseum magician kept his papyri and magical kit.

A wooden jackal sculpture draped in layers of linen and adorned with a floral wreath was found on top of an actual chest inside Tutankhamun’s tomb, guarding the innermost room. Inside the chest were numerous linen-wrapped objects: faience models in the shape of a meat joint (an ox-leg, for instance), shabti-figures (miniature mummies, who could be animated to provide labour in the afterlife), djed-amulets, a lump of resin, and jewelry or ornaments. These were almost certainly the remains of materials used in a ritual performance during Tutankhamun’s funeral – the ultimate magic show, given that the death of a pharaoh meant that the fate of both king and country were at stake.

Wooden, linen-wrapped jackal on a shrine fitted with carrying poles, seen here as found in the tomb of Tutankhamun.

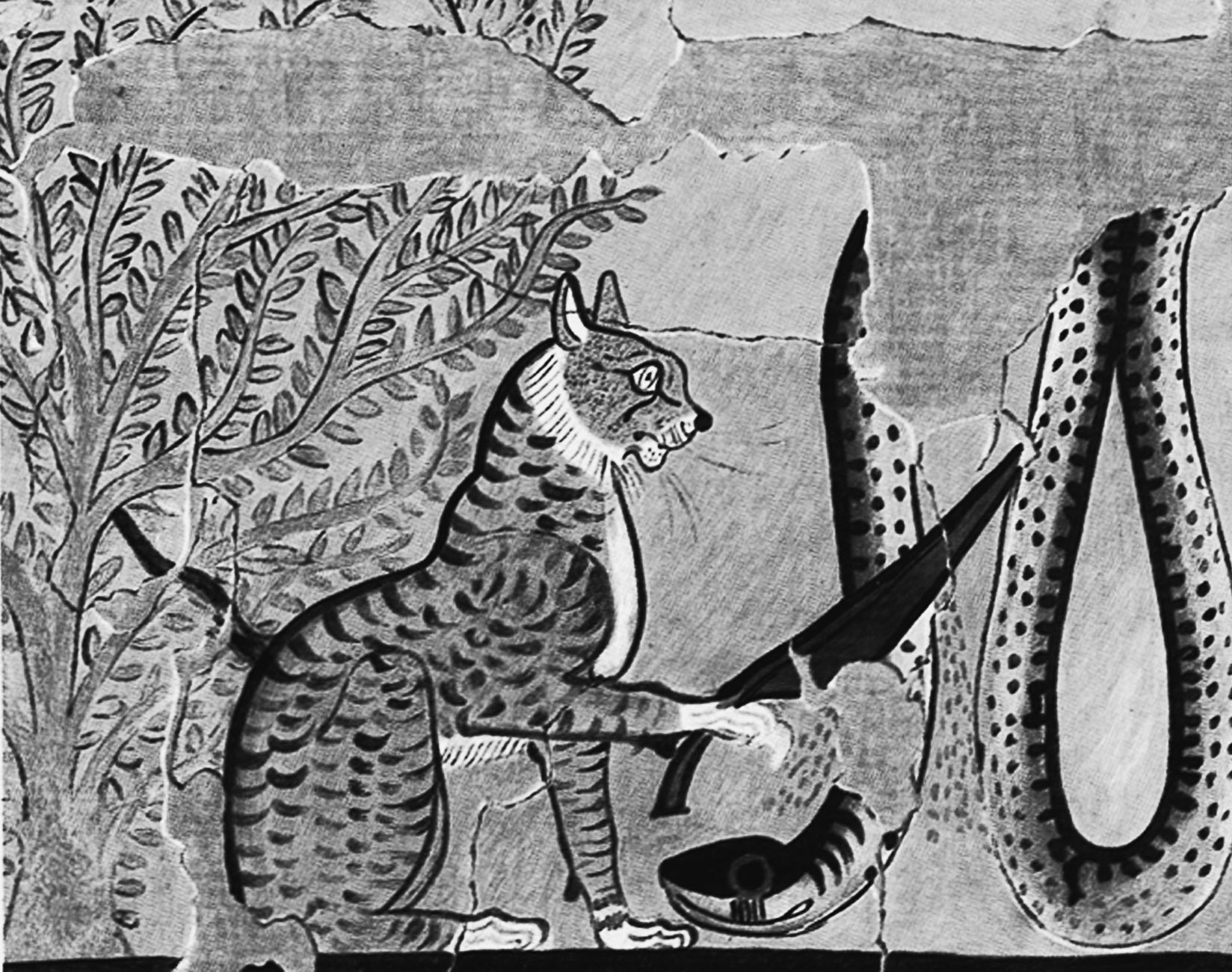

A wild cat kills a serpent in this modern copy of a painting from the tomb of Sennedjem at Deir el-Medina.

As well as dogs, famously, the Egyptians worshipped cats, though perhaps less zealously than is popularly imagined. Both domesticated and wild cats were admired as hunters in ancient Egypt, and as we have seen hunting was a metaphor for overcoming dangerous forces. A tawny wildcat helped the sun-god defeat the evil serpent Apep, and in illustrated versions of the Book of the Dead, a cat looking rather pleased with itself slices a snake’s body in two with a knife. The same collection includes a spell to animate a cat amulet, specified as being made of the blue stone lapis lazuli, although perhaps faience was more likely:

Oh cat of lapis lazuli, great of forms, mistress of the embalming house, grant offerings to So-and-so in the Beautiful West!

The ‘Beautiful West’ was the cemetery where the amulet’s owner would be buried. Being ‘great of forms’ meant having multiple manifestations or bau, the spirit forms that were a sign of how powerful a god or a spirit was.

Cats were also linked to several goddesses, none more so than Bastet, who had a huge temple in her honour in the Delta. Like Sekhmet, Bastet protected the sun-god Ra. In fact, in her earliest forms, she too had a lioness’s head. Later on, though, Bastet appeared in art as a beautiful woman with the head of a domesticated cat. Hundreds of bronze sculptures of cats were dedicated at shrines and temples in her honour, whether to help make a prayer, give thanks, or commemorate an event. Amulets of cats also proliferated, suggesting that the image of a cat had multiple uses as a protective or healing symbol. Without veterinary sterilization, a healthy female cat can give birth to a litter of kittens every few months. This made the cat a symbol of fertility and maternal care, as anyone who has seen a cat looking after her kittens can appreciate.

Leaded bronze statuette of a cat, designed to hold a mummified kitten.

The flip side of feline fertility was that there were an awful lot of cats and kittens around in ancient Egypt. Thousands of mummified cats and kittens have been discovered in temple sites and cemeteries, where they were deposited as offerings to the gods. There are also a handful of examples of cats buried in their owners’ tombs after a long, happy life; one, named Ta-Miaw (‘The she-cat’), belonged to a son of King Amenhotep III and was buried in her own carved limestone coffin. However, most of these mummified moggies were hastened on their way to the afterlife by human hands – snapped necks or death by drowning gave embalmers the body they needed to make an attractively wrapped cat bundle. Alternatively, they made do without; some cat-shaped mummies contain no more than a mixture of earth and pebbles. It was the wrapping, and a priestly blessing, that mattered when it came to offering a cat mummy and asking for divine intervention. With a little magic, any of these sacred cat-shaped creatures might have done the trick.

The practice of dedicating mummified cats (and other animals) to the gods flourished from around 600 BCE into the Roman period – exactly the time when contact between Egypt and the northern Mediterranean was increasing. Greek and Roman authors who visited or read about Egypt were baffled by the Egyptians’ fondness for cats, and we owe them several stories that sound like tall tales. In the 1st century CE, Diodorus of Sicily reported that killing a cat was a crime in Egypt, and claimed that a Roman official had been put to death by a mob for doing just that, back in the days of Cleopatra’s father. The historian Polyaenus, writing in the 2nd century CE, stretched even further back in history for his cat-obsessed tale. When the Persian king Cambyses invaded Egypt around 525 BCE, Polyaenus wrote, he hit on a successful military tactic: the Persians placed cats all along their front lines, which stopped the Egyptian army from attacking for fear of causing harm to the tabby army.

The pharaoh himself could be represented as the most famous Egyptian feline hybrid: the sphinx. We owe the name ‘sphinx’ to ancient Greek, however; there is no equivalent word in ancient Egyptian, because each sphinx simply represented a particular king. The massive sphinx that stands before the pyramids at Giza is an exception, since it came to be worshipped in its own right as a form of the sun-god. A sphinx had the body of a lion and a human head, covered by the pleated linen headdress called a nemes, worn by kings and associated with the radiant light of their divine nature.

Egyptian mythology included many other composite creatures based on lions, such as the ram-headed lions that lined the routes to temples. Two lions, back-to-back, with the sun rising or setting between them represented the god Aker, who guarded the western horizon – the entrance to the netherworld. One lion was named ‘yesterday’ and the other ‘tomorrow’. Lions on their own also had protective qualities, and often appear in miniature form as amulets and on magical implements, like a carved stone rod or staff that seems to have been part of a magician’s equipment. The lioness was not a force to be trifled with, either. Given to fury and foul moods, during which she brought disease to humankind, Ra’s daughter Sekhmet always appeared with the head of a lioness. Offerings of beer and other treats helped to pacify her, while her priests worked hard to cure the various ailments she caused.

Magic rod carved with protective animals, in glazed steatite.

Limestone stela honouring the sphinx-god Tutu and the dwarf-god Bes.

Later in Egyptian history, a sphinx-shaped god named Tutu developed a popular following in several parts of Egypt, including the Dakhla Oasis, where settlement expanded under Roman rule. With knives in his paws and solar rays streaming from his head, Tutu was known as the ‘master of demons’. Thanks to his demon-driving powers and knife-wielding form, Egyptologists used to assume that Tutu was a sort of demi-god or demon himself, who could be called on in magic spells. More recent research suggests something quite different, however. Tutu seems to have in fact been a manifestation, or bau, of the solar creator-god Amun-Ra, and images of Tutu appear mainly inside temples, rather than in domestic contexts or among magic spells and equipment. As a mighty god who could control demons, perhaps he was too frightening a figure for a magician to call on directly. In any case, confusion over Tutu’s role underscores the difficulty of separating magic from other religious practices in our interpretation of ancient culture. We can only understand magic and myth, not to mention art and religion, as interconnecting parts of a supernatural whole.

The cobra-goddess Wadjet and vulture-goddess Nekhbet, protectors of the king.

Snakes are the animals most frequently encountered in Egyptian magic, from the wands or staffs that magicians used in magic rites, to the variety of gods, demi-gods, and demons described and depicted in snake form. With its distinctive sideways locomotion, habit of appearing silently and suddenly, and a dangerous, potentially lethal, bite, the snake epitomized danger. No wonder Apep, arch-enemy of Ra, took the form of a gigantic serpent slithering through the Duat, and Isis enchanted a wax snake to inject venom into Ra to learn his secret name.

Because snakes were so formidable, they could also channel the forces of protection. Hence the fiery-mouthed cobras placed at the four corners of a room to ward off nightmares, as we saw in the last chapter. Of all the snakes known to the ancient Egyptians, the hooded cobra was especially significant. The cobra was an aspect of the sun and thus embodied its powerful heat, emitting venomous flames to save the king, magically, from harm. As the uraeus on the king’s forehead, the cobra represented Wadjet, a Delta-based goddess who was one of the two traditional goddesses who protected the pharaoh. (The other was Nekhbet, from the south of the country, who was shown instead as a vulture.)

Many other goddesses took the form of snakes as well. The goddess Renenutet, associated with agricultural fertility, often had the body of a cobra, while Meretseger, ‘she who loves silence’, sometimes appeared as a cobra and sometimes as a woman with a cobra’s head. Meretseger was worshipped on the distinctive pyramid-shaped mountain that overlooks the cemeteries on the West Bank of the Nile at Thebes (modern Luxor). This goddess seems also to have had associations with fertility and nourishment. An unusually high number of dedications made to her at the village of Deir el-Medina were donated by women, including a stela that represents a dozen slithering snakes in place of a human figure of the goddess. The stela’s prayer is in honour of Wab, the woman shown kneeling at the bottom.

Another reptilian creature, the crocodile, inspired endless magical actions and myths. Moving between the water and the land, crocodiles occupied a similar borderland to hippopotami in the ancient Egyptian imagination, and they could similarly be friend or foe. Crocodiles are extraordinarily dangerous creatures, with even a young adult capable of killing a human in minutes. In tomb paintings that show vulnerable, precious cattle crossing a canal, a crocodile often lurks threateningly below the water line. The herdsmen have a magician to help with that, however. He makes a magical hand gesture (two fingers pointing out, and two folded into the palm) and recites a water spell to protect the herdsmen and their cattle from the ‘marsh-dweller’ by rendering the crocodile blind.

Warding off the crocodile meant warding off death itself, given the killing power of these swift-moving reptiles. But turn that murderous power to your own ends, through magic, and crocodiles came in handy, as we saw in Chapter 1, where two drawings of crocodiles completed the folded-up papyrus amulet a magician had made for his client. These drawings may evoke one of the beneficent crocodile gods, of whom Sobek was the most widely known and worshipped, especially in the Fayum region. One temple in the Fayum Oasis honoured twin crocodile gods who were identified, in Roman times, with the youthful Horus and his father Osiris. Priests of Sobek raised crocodiles in temple quarters, and young mummified crocodiles served as sacred offerings, in much the same way as cat mummies. So much better than turning them into shoes and handbags.

Stela dedicated by Nebnefer to Meretseger, a cobra-goddess identified with the highest mountain of Thebes.

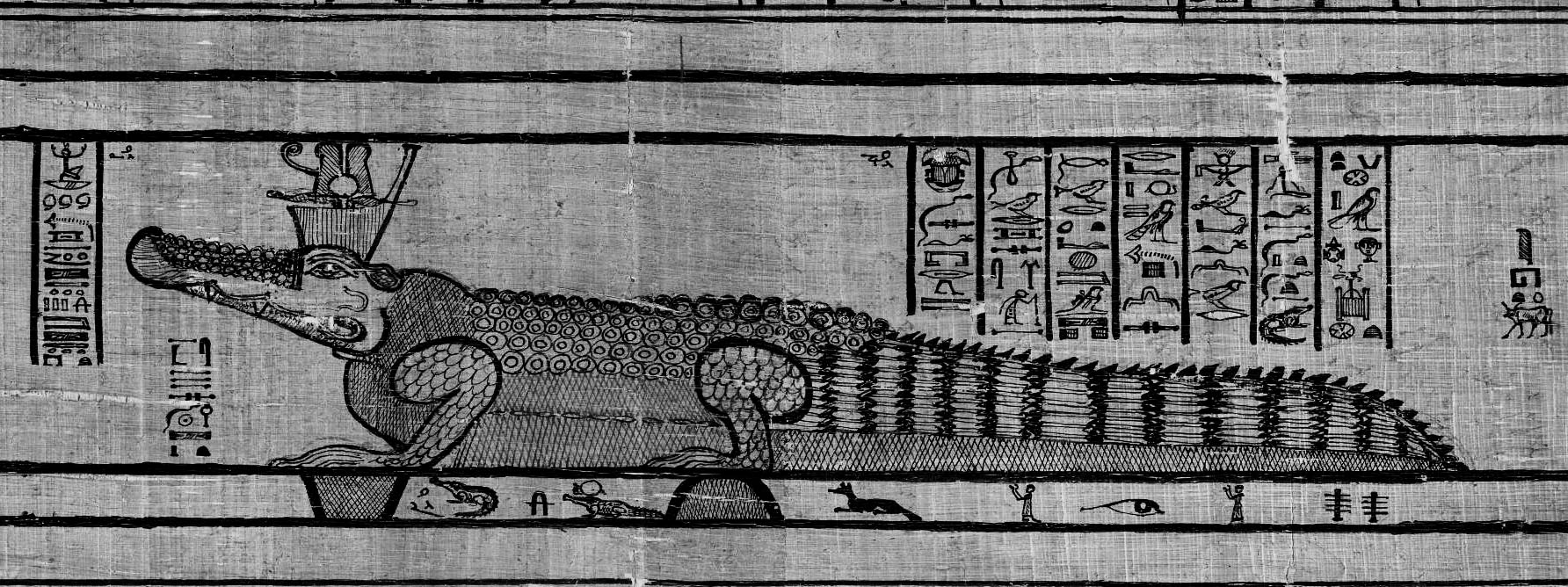

The constellation Ursa Major, here associated with a hippo-goddess, from the Book of the Fayum.

The crocodile was the most recognizable, and deadly, part of the hybrid creature called Ammut (literally, ‘devourer of the dead’), who was depicted slavering expectantly near the balance scales during the weighing of the dead person’s heart in the judgment ceremony. Ammet had the head of a crocodile, the mane and foreparts of a lion, and the rump of a hippopotamus. Another crocodile hybrid had an entirely different, more peaceable character, however. Taweret – literally, ‘the Great One’ – had a hippopotamus body with the paws of a wild cat and the tail of a crocodile. Taweret always appeared standing upright on her hind legs like a human, with breasts that had been stretched out by nursing babies. This gives a clue to Taweret’s role as a deity who protected expectant mothers and young children, as does the sa-hieroglyph she often rests her front paws on. Taweret carries protection before her, like an amulet within the amulet of her own incredible animal form.

A monstrous-looking body did not mean that a supernatural being had a monstrous character. Quite the opposite was often true. A similar-looking figure to Taweret, with an entire crocodile forming her backbone, was identified with the constellation we know as the Great Bear (Ursa Major) and with the goddesses Ipet, Neith, and Nut, all of whom also had special connections with motherhood and birth. The crocodile on the back of this Ipet/Great Bear goddess was a fusion of Sobek and Ra, and it was through her mighty body that these creator-gods could be reborn as they travelled through the starry night.

The crocodile-god Sobek, from the Book of the Fayum.

It wasn’t all hefty hippos and lordly lions for an Egyptian magician. He had to be able to deal with much smaller creatures, too. One of the most common amulets found in faience or carved stone is the scarab, a beetle with the distinctive habit of laying its eggs in dung, which it then rolled into a ball to nurture them into life. This action might have led ancient Egyptians to associate the scarab with the sun, so that the scarab was often shown holding or pushing the solar disk between its front legs. The scarab developed its own layers of mythology over time. The god Osiris was said to have a scarab beetle under his head, which emerged with wings that allowed it to fly up into the sky – a sign of his regeneration. In magic, a scarab could be worn as an amulet or used with mud, clay, or wax as a seal, for instance to close a roll of papyrus or the looped cord that held two doors or a lid closed shut. Sealing brought together the magical tools of writing and secrecy, and seals were also made in the form of hedgehogs and hares, creatures that could also possess protective powers, it seems.

In contrast to scarab beetles, which are overwhelmingly positive symbols, the scorpion was always bad news. Scorpion stings are rarely, if ever, life-threatening, but they are extremely painful. As we saw in Chapter 2, magicians known as scorpion-charmers accompanied mining expeditions into the desert, where scorpions were a professional hazard. Associated with the goddess Serket (or Selket), the scorpion symbolized all kinds of pain and suffering, and magical exhortations aimed at overcoming the scorpion’s sting were no doubt meant to keep a range of troubles at bay. The child Horus grasped scorpions in his hands to demonstrate his power over them as a symbol of his rightful dominion over the cosmos, while the soles of some mummy cases depicted scorpions that the deceased would crush safely underfoot, thereby defeating evil and overcoming death itself.

Scorpions on the underside of a mummy’s footcase would be trampled and magically defeated.

Although feathers are not explicitly called for in magic spells as a tool or an ingredient, you couldn’t move in the supernatural world of ancient Egypt without feeling, hearing, or seeing the swoosh of a bird’s wing. Birds are not really of this world, after all. Their ability to fly, their brightly coloured plumage, and the sound of their calls, singly or en masse, all made birds seem like messengers from another world. Egyptian texts compared the colour of birds’ feathers to the spectrum of the sun’s rays. The graceful, encompassing curve and flare of outstretched wings gave artists and magicians alike a perfect symbol for other-worldly powers of protection, while the beating of wings in flight captured the sensation of a breeze or wind, both natural phenomena that might signal supernatural presence. The creator-god Amun of Thebes was credited as ‘master of the winds’ in magic spells written during Ptolemaic and Roman times, but the idea had much earlier roots. The magician-priest prayed to Amun, ‘ruler of all’, in order to access the powers of creation that wind – and by extension, wings – represented.

The spirit forms of human beings could take flight, too. The ba of a person who had died was represented as a bird with a human head. If the magic performed during mummification and burial had worked, the ba could fly out of the tomb by day, returning to the mummified body each night for a cosmic reunion and renewal. The most elevated spirit-forms of the dead, the akhu, were represented by the hieroglyphic sign of a crested ibis. The akhu were ‘the luminous ones’, associated with dazzling light. Being a bird really was divine.

Other birds that appeared frequently in Egyptian art and on magical objects were the vulture, which was associated with the goddesses Nekhbet and Mut, and the African sacred ibis, which was always identified with Thoth. Hundreds of thousands of mummified ibises were dedicated at temples, stacked in special underground chambers along with mummies of Thoth’s other sacred animal, the baboon. As with the kittens and young crocodiles that were mummified as offerings, these birds and baboons met premature deaths in order to serve what was, to the ancient Egyptians who donated them, a higher good.

Birds of prey – specifically the falcon and the red kite – brought to divine symbolism the added appeal of their impressive speed and hunting ability. Ra and Horus are the two male deities best known for taking falcon form, but there were many more. The temple of Horus at Edfu kept a sacred falcon in a specially built cage high up on the temple gateway. His mother Isis and her sister Nephthys instead took the form of red kites. The keening cries of these birds were likened to the wails the two sisters made as they mourned the murder of their brother Osiris. Isis sometimes took the form of a kite during the mystical love-making that allowed her to conceive Horus from Osiris’s reinvigorated dead body.

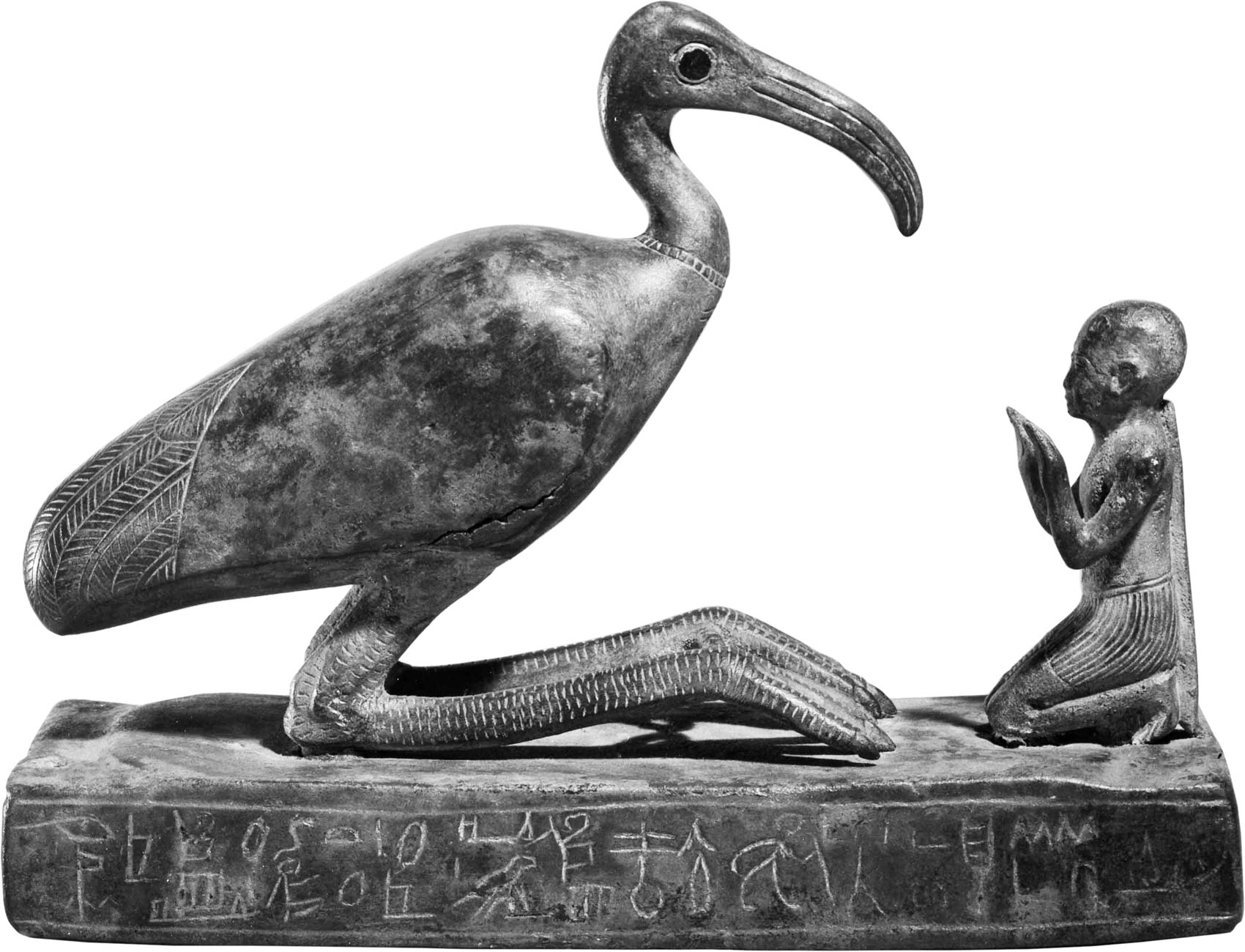

The priest Padihorsiese dedicated this bronze ibis to Thoth.

Many goddesses, especially Isis, Nephthys, and the sky-goddess Nut, had outstretched wings added to their human arms when they were represented in art. So, too, did Maat, the goddess who personified truth and cosmic justice, against whom – in the form of a single feather – the deceased were judged. Overlapping wings painted onto coffins, or stretched around the corners of sarcophagi, brought magical protection to the person buried inside. Feather patterns on garments and furniture must have had a similar function, as well as giving everything they adorned a bright, blazing appearance.

Red kites representing Nephthys (left) and Isis (right), either side of a wrapped mummy in the tomb of Queen Nefertari.

Wings were often attached to animals who didn’t actually have them on amulets, in particular the scarab and the ram, both of which were aspects of the sun god and thus perfectly suited to the feathery symbolism of sunlight, colour, and air. A sheet of papyrus probably cut from a magician’s handbook shows the extent to which bird anatomy contributed to the perception of the supernatural. From a human body, a figure sprouts two pairs of arms and two sets of wings, as well as the tail-end of a bird. He holds was-sceptres that symbolize power and some lethal-looking arrows and knives. The creature also has several animal heads, including lions, crocodiles, and rams, and his body is covered with protective knots. Individual flames surround the entire figure, and he stands – with serpent-shaped feet – on a ring that encloses several harmful forces: a scorpion, snakes, a crocodile, two jackals, and a pig, the pig being another animal that was associated with Seth. Although the rest of the papyrus isn’t preserved, this illustration may have been part of a handbook of spells, used to help a magician conjure a god whose formidable hybrid appearance would work to defend the magician and his client. In the magical menagerie of ancient Egypt, feathers were a magician’s best friend.

Fragment of papyrus with a magician’s drawing of a winged god surrounded by protective flames.