INTRODUCTION

PRESIDENTIAL DOODLES: A BRIEF HISTORY

SOON AFTER SOMALI MILITIAMEN KILLED EIGHTEEN AMERICAN SOLDIERS in Mogadishu on October 3, 1993, President Clinton convened his national security team in the White House. As recalled by the counterterrorism expert Richard Clarke, the president sat silently as his aides reviewed the situation. Then, Clarke wrote, “When they had talked themselves out, Clinton stopped doodling and looked up. ‘Okay, here’s what we’re going to do.’” 1

Apart from the atypical decisiveness Clarke attributes to Clinton, what strikes the reader in this passage is that amid the most severe international crisis of his tenure to that point, the leader of the free world was, of all things, doodling. We imagine meetings of the National Security Council to be efficiently run affairs where matters of the utmost gravity are discussed; we don’t expect the president to be dithering, daydreaming, or making little drawings. But here, while Warren Christopher, Les Aspin, and Colin Powell held forth about matters of global consequence, the commander-in-chief was scratching out idle marks on a pad of paper. What makes it more interesting, the activity wasn’t evidence of dereliction of duty, a sign that he wasn’t paying attention. On the contrary, in Clarke’s telling, it indicated supreme confidence: Clinton could afford to doodle because he already knew what had to be done.

Clarke isn’t the only writer to use the image of a high official scribbling away to achieve dramatic effect. The historian Herbert S. Parmet writes of the cool contempt that Secretary of State John Foster Dulles showed to his British counterpart, Anthony Eden, in the 1950s: “It must . . . have galled Eden to address Dulles while the American doodled on an ever-present legal-sized yellow pad, only glancing upward occasionally and rather quizzically . . . as though the forthcoming words were perfectly predictable.” Eisenhower’s science adviser, George Kistiakowsky, wrote of how the president himself, on hearing an aide discuss the mounting danger posed by the Soviet Union, “quite suddenly stopped his usual doodling, raised a hand, and said: ‘Please enter a minority report of one.’” John F. Kennedy was, according to Peter Edelman, a former aide to Robert Kennedy, “doodling ‘poverty’ on a yellow legal pad at the last cabinet meeting before he died.” In some cases doodles—or their near kin—have entered political lore. Supply-side apostle Arthur Laffer scrawled on a cocktail napkin the chart that would guide Reaganomics. Reagan’s aide Pat Buchanan later got in trouble by jotting “succumbing to the pressure of the Jews” over and over in a meeting about whether to scuttle the president’s visit to a Nazi graveyard. George W. Bush scrawled “not on my watch” on a memo about the Rwandan genocide—words used against him as Sudanese were slaughtered in Darfur.2

The image of a president doodling can have all kinds of effects. It may jar us through its juxtaposition of high-stakes drama and mundane habit. It may disturb us by exposing the world’s most powerful man’s childish side (Reagan drew babies and horses). It may shock us by suggesting a contempt on the doodler’s part for the interlocutors he’s ignoring. Or it may delight us to see how an offhand note can poetically express what reams of formal communication could not.

Whatever their particular effects, there’s no denying that presidential doodles are intriguing. The question is why.

Doodling is an ancient habit. Prehistoric South African cave drawings and Mesopotamian clay tablets bear errant marks unrelated to their main subject matter. Yet only in the twentieth century was the word doodle used to denote an absentminded scribble and people began to study the form. And the most popular prism of interpretation has been the psychoanalytic, as aficionados scrutinized doodles for the insights they may offer into the unconscious thoughts lurking in the recesses of the artist’s psyche.3

The first person to recognize—or at least to cash in on—this now-familiar notion was a colorful mid-twentieth-century character named Russell M. Arundel. Born in 1902, Arundel worked as a journalist and Capitol Hill staffer in Washington in the 1920s and 1930s. He showed an early interest in the images of presidents when he served on the Mount Rushmore Memorial Commission. Later, as a lobbyist for the sugar industry, he developed a friendship with Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and was hauled before a Senate committee for signing over a $20,000 check to McCarthy, allegedly as a loan. In 1949, Arundel achieved still more notoriety by purchasing a small island off the coast of Nova Scotia, naming it the “Principality of Outer Baldonia” (even though it remained part of Canada) and nearly provoking hostilities with the Soviet Union. He spent his final decades running a Pepsi-Cola subsidiary and serving as a leading figure in the Virginia fox-hunting scene.4

For all these feats, Arundel’s most precious achievement may be his 1937 book, Everybody’s Pixillated, a compilation of doodles by famous figures, including Cab Calloway, Helen Hayes, Huey Long, and the Duke of Windsor. (The volume also contained an impressive selection of doodles by presidents, some of which appear in this book, but apart from the inimitable Herbert Hoover, the most proficient presidential doodlers—Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Reagan—came to office after Arundel’s fancy had turned to steeplechasing.) Arundel grasped the nature of the modern instinct for doodling. “Place a pencil and pad near the telephone of any human of more than primeval intelligence and the bet is ten to one that he’ll doodle during his next telephone call,” he wrote in Everybody’s Pixillated. “Whether teamster or genius, he will produce triangles, circles, arrows, mice, stars or some other penciled designs and tie them together in a pattern which mightily resembles surrealism in a lunatic asylum.” 5

For all his acuity and measured whimsy, Arundel was in the grip of a pop Freudianism that still pervaded American culture in the 1930s. As W. H. Auden wrote a few years later, Freud had become “no more a person/Now a whole climate of opinion.” His work influenced filmmakers and sociologists, poets and policy analysts. It made sense, of course, to regard the doodle as a relative of the Freudian slip or the verbal free association—an articulation of repressed truth unleashed by the unconscious while the ego was looking the other way. Doodles, as Arundel put it, “are psychic blueprints of man’s inner thoughts and emotions that have slipped from the deeps of memory onto paper.” Accordingly, he interpreted the doodles in his book as revealing aspects of their authors’ personalities. He even included in the book a ten-page “Pixillation Chart,” featuring 120 common doodles and corresponding thumbnail analyses so that readers could probe their own psyches as well as those of the celebrities whose jottings Arundel had culled.6

This Freudian approach to doodle interpretation has since held sway. A 1947 article in the New York Times Magazine that reprinted samples from Arundel’s collection concluded that in doodles “the subconscious may yield a great store of dreams, fancies, inspirations—and even the most carefully guarded fact.” A 1982 Time magazine feature on presidential doodles took a similar line.7

There were, however, dissenters from this dominant wisdom. Norman R. Uris, the author of a 1970 doodle compilation, was resolutely anti-analytical in contemplating the drawings he gathered from such celebrities as Betty Grable and Julian Bond. “To me, doodling is an art form and is no more or less symbolic than the work of any artist,” Uris asserted. “Doodles may be interesting, but you can’t judge what or who a person is—or isn’t—by looking at his doodle.” 8

Still, you don’t have to turn the doodle into the key to the unconscious to realize that it’s not just any ordinary drawing. Doodles are practically sui generis (especially among presidential communications) because they aren’t meant for anyone else to see. As UN Undersecretary General Ralph Bunche replied when Uris asked him for a contribution to his book: “To do a doodle to order would really be faking, because a doodle ought to be spontaneous and subconscious. In fact, since receiving your letter, I have found that my doodling is spoiled because the letter has made me self-conscious about it.” (Other luminaries also rejected Uris’s request for doodles, though most did so on less principled grounds. “I must confess, I don’t know what is a ‘doodle.’ I did not find this word in the Oxford Concise Dictionary,” replied Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion. “Will you explain to me what is a doodle?”)9

For all those who declined to help, Uris was able to secure a doodle from President Richard Nixon—a particularly impressive feat because Nixon had declined (through his aide H. R. Haldeman) to give one to his own speechwriter, William Safire, who was also a collector. Perhaps Nixon, who had a lot to hide, was afraid that psychologists would try to read his unconscious; despite his outward loathing of them, Nixon actually had a strong penchant for thinking psychoanalytically. On one occasion he admitted that he tried to decipher other people’s doodles. “I always watch my opposite numbers to see how they doodle,” Nixon told his ghostwriter Frank Gannon in a post-presidential interview. “I draw squares and diamonds and that sort of thing. . . . [I’m] probably a square doodler,” he confessed, in a clever if unintentional pun. Nixon continued: “I noticed that, for example, in 1972, when we were having our first discussion with Brezhnev about missiles. We—the argument was as to whether or not a big missile could be put in a smaller hole. . . . While we were talking about it, he would draw holes and then missiles . . . to see whether or not they could go in the holes and so forth and so on. And down here, when we were meeting in a cabaña looking out over the Black Sea, he doodled—in this case, he drew a heart with an arrow through it. I don’t know what that signified, but that was when we were failing to reach agreement on a proposal to limit [nuclear warheads], which we had proposed and which they had rejected.”10

Nixon, unfortunately, didn’t develop his interpretation of Brezhnev’s artwork. Yet it’s less the meaning he might have ascribed to his counterpart’s doodle that merits note than the very instinct to interpret it at all. Not that Nixon’s propensity is so unusual: despite the dissenting strain that insists on seeing doodles (and slips of the tongue) as innocent of meaning, the impulse to read doodles psychoanalytically remains all but irresistible. These days it pops up in women’s and teenage girls’ magazines. “Discover What Your Doodles Say About You,” promises a headline in Mademoiselle. “Doodles & Squiggles: What They Reveal,” echoes a feature in ’Teen.11

Alas, for all the parlor-room fun it can provide, this approach to thinking about doodles isn’t wholly satisfying. The problem doesn’t lie with Freudianism, but rather with its tenuous application to doodling. It is ultimately impossible to use Freudian concepts to definitively understand subjects without direct, extensive access to the people themselves. And so the analysis of any doodle will inevitably be strictly speculative. (Psychologists often make this point. Back in 1947, the shrinks Charlotte Kamp interviewed for her New York Times Magazine piece warned that “a really effective interpretation requires some familiarity with the person involved, so that known mental and emotional factors can be associated with the symbols and patterns that go down on paper.”) Ultimately, sad to say, we can glean only limited insight into our presidents’ inner lives from their White House scribblings.12

The appeal of presidential doodles, then, must be located in realms beyond the purely psychoanalytic. We must look also to the American people’s longstanding love-hate relationship with their most powerful officer, the president.

Americans have harbored ambivalent feelings about the presidency since the office was created. Having thrown off the British monarchy, the colonists insisted on establishing a republican government in which the people would be sovereign—without any sort of magistrate that might so much as resemble a king. But their first stab at a national system, the ill-starred Articles of Confederation, failed precisely because it did not provide for an executive branch—leaving the country united only by what George Washington called “a rope of sand.” To remedy the problem, colonial leaders in 1787 convened the Constitutional Convention, where they drafted a new regime that included a strong presidency.13

Ever since, the popular desire for both purposeful leadership and an egalitarian system has created a contradictory attitude toward the presidency. Despite the early hopes for a weak executive, the president—as the head of state as well as the head of government—took on a ceremonial grandeur that could be distressingly king-like. The unanimous choice of George Washington to inaugurate the office in 1789 enhanced its mystique. “Babies were being christened after him as early as 1775,” Marcus Cunliffe wrote of Washington, “and while he was still president his countrymen paid to see him in waxwork effigy.” Although Washington reassured the country that he had no monarchical pretensions, his stature inevitably invested the office with majesty.14

This veneration for the president has remained acute—even in this cynical modern age. The most powerful official in government, the president comes closer than any other individual to embodying the nation itself. Theodore Roosevelt once remarked after a tour of the West that people had come to see him because of their “feeling that the president was their man and symbolized their government . . . they had a proprietary interest in him and wished to see him . . . they hoped he embodied their aspirations and their best thought.” The president still serves as a repository for such hopes and desires (and fears and nightmares). With posh inaugurations, a resplendent mansion, his own plane, and even his own theme song, the chief executive enjoys a status unmatched by any of his countrymen. Presidents, not senators, typically adorn our currency, and no chiseled mountain face bears the likenesses of our top Supreme Court justices. For all the power recently ascribed to other government officials, it’s still rare to hear a proud parent talk of wanting her child to grow up to be chairman of the Federal Reserve.15

Studies have demonstrated that the president is the symbol through which children first comprehend their government, even when they have no clue what he actually does. When a president dies, adults experience symptoms of grief they otherwise exhibit only at the loss of their own family members. Not even a president’s aides are immune from the office’s shamanistic pull. Nixon’s White House Counsel John W. Dean wrote of his mental associations upon considering how to “protect the President” during Watergate: “The President. I felt myself rising instinctively in salute. I thought of aircraft carriers, battles, strong men reverent at the mention of his name, a communications network that flashed each utterance around the world.” The president has become, too, the cynosure of Washington journalism, generating more news copy than any other American.16

For all the pomp and deference, however, Americans also know that the president is just another man. Public officers, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote, “are perfectly aware that they have gained the right to hold a superior position in relation to others, which they derive from their authority, only on condition of putting themselves on a level with the whole community by their way of life.” It was in Tocqueville’s day—when the voting public first grew in size—that presidential candidates began casting themselves as simply first among equals. Pioneering the image of president as everyman, Andrew Jackson used campaign literature touting his generosity, his humble origins, his lack of elite schooling, and his distance from Washington power brokers. His rowdy inauguration, at which hordes of drunken admirers stampeded over the White House furniture, affirmed in a perverse way the rough-hewn new president’s oneness with the people.17

Over time, other customs that separated the president from the people eroded. For most of the nineteenth century, for example, presidential contenders didn’t campaign personally. A candidate was a “mute tribune,” standing aloof from the mean business of politics while others championed him. Toward the century’s end, however, self-styled reformers, troubled by corruption and popular ignorance, sought to curb the political machines. They told citizens to judge office-seekers on their individual merits, not their party affiliations. Personality became more prominent in the presidential discourse. Reporters plied a new form of journalism—the political profile—that gave readers a fuller account of the candidates’ backgrounds and human qualities.18

Taking office in 1901, Theodore Roosevelt embodied the modern president as personality. Whereas in the 1860s the face of even a famous general such as Ulysses S. Grant was mostly unknown to Washington reporters, TR—with his toothy grin, his trademark pince-nez, and his tightly buttoned suits, reproduced in papers everywhere (thanks to the invention of the Kodak camera as well as better printing technology)—was instantly recognizable: an icon. With his activist view of the office and his native gift for newsmaking, TR magnetically drew attention to the office. His boisterous brood of children, his penchant for outrageous behavior, and his taste for consorting with the fledgling White House press corps—he held forth with reporters while getting his afternoon shave—all turned the presidency into a spigot of news for the new mass-circulation dailies. Much of it was unrelated to policy or politics, such as the 1904 New York Times article about his pet parrot, Loretta.19

Helped along by new media, TR’s successors perpetuated the personalization of the office. Under Warren Harding, a publicity hound, “clothes, tastes, pets, amusements, and habits were always on public parade,” wrote Lindsay Rogers, a political scientist of the day, “and an ex-newspaperman was attached to the White House staff to think up ways of ‘selling’ the president.” Calvin Coolidge bantered with reporters at languorous press conferences, belying his reputation for silence, and his radio addresses brought the president’s voice into living rooms for the first time. With his fabled “Fireside Chats,” Franklin D. Roosevelt used his unmatched gift for conjuring intimacy with the public to endear himself to millions.20

Even more than radio, television created a deceptive public sense of personal closeness to the president. If the new medium bolstered his clout, it also reduced his grandeur, making him appear overly familiar and smaller than life. The plainspoken Harry S. Truman, after moving back into a renovated White House, led a team of TV reporters on a tour, stopping abruptly to rattle off a Mozart sonata on an East Room piano. Jackie Kennedy reprised the gimmick some years later, minus the sonata. By the Kennedy years, pundits were discussing whether the front-page newspaper diagrams of Eisenhower’s intestines that ran during his illness or the widely seen photos of Kennedy’s bare chest at poolside meant that presidents had now forsaken their private lives altogether. (In retrospect, it’s striking how much Kennedy managed to keep private.)21

Since the 1960s, other factors have further diminished the presidency’s mystique, if not its actual power. Vietnam and Watergate dispelled much of the president’s heroic aura. The era’s skepticism toward authority made doubting, attacking, mocking, and knocking our leaders seem as reflexive as a military salute and as American as the Kentucky Derby. In 1970, George Reedy discerned “the twilight of the presidency.” In 1992, Time’s headline “The Incredible Shrinking Presidency” morphed from coinage to cliché overnight.22

Perhaps more than any of his predecessors, Nixon showed the public that presidents could possess all the ordinary vices of the common man—and some extraordinary ones too. His own machines recorded him cursing, fuming, badmouthing his enemies, and plotting petty acts of revenge. The upshot wasn’t just a more cynical view of presidents as flawed and human; it was a redoubled impulse to scour the psyches of elected leaders for signs of irrational (not to say paranoid) Nixonian behavior. This pop psychoanalytic scrutiny wasn’t new. It had gained currency in the 1950s when Nixon was vice president, a heartbeat away from the cardiacally challenged Eisenhower. In those early years of the atomic age, the scuttlebutt that Nixon visited a Park Avenue psychoanalyst fed emerging worries about the emotional stability of whoever might have his proverbial finger on the button. Similar fears destroyed confidence in Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater in 1964, whose shoot-from-the-hip style and comments about using nuclear weapons in Vietnam—coming just two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis—scared away voters. In 1972, news that George McGovern’s vice presidential nominee, Thomas Eagleton, had received electroshock therapy for depression helped force him off the Democratic ticket. Watergate simply confirmed that some link existed between private neuroses and public actions. Americans resolved to look closer the next time.23

“Character” fast became the watchword among Washington reporters, tacitly deputized by a wary public to probe the lives of aspirants to high office. Claiming “I will not lie to you”—itself a lie—Jimmy Carter shrewdly rode the character wave into the White House. As public and private converged, new and arbitrary elements of a politician’s private life—past drug use, marital infidelity, military service—were suddenly deemed fair game for journalistic scrutiny. This jerry-built conception of character didn’t produce more honest leaders, but it did help demolish the wall of propriety that once surrounded the Oval Office. The new standards were applied retroactively, too. After Watergate, biographers dredged up untold tales of Kennedy’s womanizing and flocked to the once-disreputable subject of Jefferson’s slave-owning.

The repeal of Victorian mores, underway for decades, also proceeded apace; the personal became the political, and vice versa. As First Lady, Betty Ford went public with her breast cancer and then her alcoholism. Carter confessed in Playboy to lust in his heart. Ronald Reagan’s colon was televised. When Clinton divulged to an MTV audience his preference for briefs over boxers, what was shocking wasn’t his candor but that his candor could still rile a few puritans. Sometimes even the president of the United States has to stand naked.

Today we see as many signs of the president’s ordinariness as of his eminence. Prosecutors, pundits, kibitzers, and barflies all inveigh that “no one is above the law.” Office-seekers vie to shed elitist trappings; Ivy League degrees and Mayflower pedigrees go unmentioned on the permanent campaign, as candidates boast of their common roots and contrive a common touch. Clearing brush, chopping wood, munching pork rinds, tossing the first pitch: the populist style pervades the political sphere.

Political rhetoric has grown more familiar. Reflecting our therapeutic ethos, presidents use “I” and “you” more than they used to and babble to reporters about their feelings as if confiding to a therapist. The presidential family has become a mainstay of campaign-trail theatrics. After his groundbreaking use of autobiography in his 1952 Checkers speech, Nixon won fame—and shame—for trotting out his wife, Pat, and his daughters as verbal and physical props; “George Washington never said how glad ‘Martha and I’ were for the tributes of the crowd,” sneered JFK supporter and historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., in 1960. A generation later the tactic wasn’t even controversial. George Bush, Sr., explained that seeing Michael Dukakis’s son on TV in 1988 led him to respond in kind. “We’ve got a strong family, and we watched that and we said, ‘Hey, we’ve got to unleash the Bush kids.’ And so you saw ten grandchildren there, jumping all over the convention.” They’ve been jumping ever since.24

Political audiences, as much as political consultants, have contributed to the humanizing of the presidency. A book-buying, Booknotes-watching public devours the newly minted genre of “presidential history,” whose bestselling works dwell less on policies and ideas than on personal lives: Washington’s character, Adams’s marriage, Jefferson’s slaves, Lincoln’s depression, FDR’s affairs, Kennedy’s illness, Johnson’s ego. We seek these glimpses though the Oval Office curtains because they promise to let us reconcile our ambivalent feelings toward the president: in revealing our fascination with his every tic, we pay obeisance to his importance even as we cut him down to size.

Probably the most important factor whetting this appetite for details about the personal lives of presidents has been the transformation of presidential politics into a vast made-for-TV spectacle. With a mammoth apparatus of speechwriters, press officers, pollsters, and image-makers at the president’s disposal, any glimpse of his private side now promises a smidgen of authenticity in an otherwise never-ending political drama. Hence, we’re tantalized by a chat with the First Lady, a purportedly spontaneous “town hall” meeting, a secret White House tape, a gaffe uttered unwittingly into a live microphone or on a rolling camera, a choke on a pretzel—and, perhaps, a presidential doodle.

Presidential doodles are intriguing, above all, because they provide us with a glimpse of the unscripted president. They’re the antithesis of the packaged persona. Made with neither help from speechwriters nor vetting by a focus group, a doodle is the ultimate private act; its meaning may remain opaque even to the doodler himself. As a result, it renders the president human in ways that a staged family outing cannot. And if we can’t make conclusive judgments about what a president’s drawings reveal about his innermost fears or fantasies, his doodles can still be suggestive and provocative. They’re of interest cumulatively: side by side, the scores of doodles in this book reveal the range and diversity of the styles and mental habits of the men who have led this country. Collectively they help in a benign and inviting way to demystify the office—to build a bridge between citizen and leader.

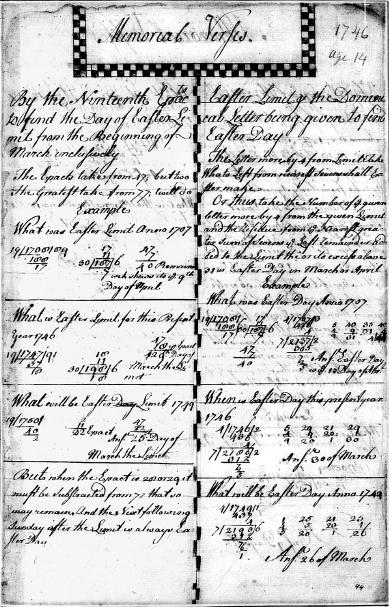

The styles of presidents and the copiousness of their output vary widely, and they tell no neat chronological story. Yet over the long term, some evolution in the presidential doodle can be discerned. For the earliest presidents, true doodles are hard to find. The scribbles included herein by George Washington, the John Adamses, and a few others come from boyhood copybooks or diaries or pre-presidential notes. Still, in their elegant or haphazard scrawls—or in Thomas Jefferson’s architectural drawings and codes for writing secret letters—we see gratuitous flourishes, absentminded repetitions, and daydreamed designs that exude the kind of unmistakable pointlessness that makes a doodle a doodle.

Full-fledged presidential doodles start to appear in the 1820s and 1830s, with Presidents Jackson, Van Buren, and William Henry Harrison. On the whole, however, the nineteenth-century record is sparse, at least when compared to the doodle-rich twentieth. To what extent our long-ago presidents idly etched is, unfortunately, unknowable because many didn’t keep their papers. It’s a sad fact for a presidential buff to learn that for most of American history, presidents privately owned their official papers and many collections were lost, destroyed, or scattered among different libraries. The Library of Congress opened its Manuscript Division in 1907 and set about acquiring what remained of many presidents’ collections. But even among those that survived, how much had been deemed expendable and discarded along the way is unknown.

That changed in 1939, when FDR decided to donate his papers to the federal government and provided land on his Hyde Park estate for archives to house them—the first presidential library. Roosevelt even sketched plans for the building (and for such details as the lighting fixtures) in doodle-like designs. His friends and associates raised the necessary funds.

Roosevelt’s successors followed this model, in which the public owned and the government administered presidential papers, with private financial support. In 1955, Dwight Eisenhower made this formula official by signing the Presidential Libraries Act. But two decades later, Nixon’s conduct in office exposed the need for reform. Nixon had not only tried to abscond from the White House with incriminating documents but also deducted a half-million dollars from his tax returns for donating his papers to the government, in order to reduce his tax bill. Believing that access to presidential papers shouldn’t hinge on the charity of the president himself, President Carter signed the Presidential Records Act in 1978. The law declared any records documenting the president’s constitutional, statutory, or ceremonial duties to be public property—a broad net that has, happily, swept up some classic doodles in its haul. Of course, some presidents have found or created loopholes. George Bush, Sr., exploited the provision that allows presidents to designate papers as “privileged” and keep them private, and his papers that are open to the people contain almost no doodles.

Despite such connivances, presidential doodles have proliferated in the twentieth century. The reasons are many. History became professionalized in modern times, placing new importance on bureaucratic record-keeping. The executive branch exploded in size, creating larger, longer, and more frequent meetings in which a president might find himself with just a pen or pencil to occupy himself. Improvements in photocopying meant more paper lying around. The telephone became an indispensable tool, leaving nervous presidential hands idle.

It makes sense, then, that Herbert Hoover, who never met a pencil and scratch pad he didn’t like, was the first prolific presidential doodler. Hoover’s doodles are also historic as the first to enter the public realm. In 1929 an autograph collector named Thomas Madigan bought a Hoover drawing that a White House visitor had taken home, and his purchase garnered extensive newspaper coverage. Articles crowed that the published images would allow readers “to analyze and otherwise sound the mental depths of President Hoover’s mental makeup and inner personality, just as it is done in the best psychological circles.” Eventually, a dressmaker turned Hoover’s design into a pattern for children’s rompers, one of which Hoover’s granddaughter Peggy Ann is said to have worn.25

Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman also doodled, but it wasn’t until Dwight Eisenhower took office that Hoover faced a challenge for the presidential doodling crown. A Sunday painter who liked to set up his easel in the White House, Eisenhower put his artistic training to work with pencil and paper during innumerable cabinet and National Security Council meetings. Only after his presidency, however, did the Eisenhower Library put fifteen of these drawings on display—a motley selection of nuclear images, weaponry, tables, pencils, and self-portraits (with hair). John F. Kennedy’s doodles were similarly put on public view in the year after his death; they also inspired a sculptor to turn them into “Doodles in Dimension,” using steel, aluminum, and wood. More recently, presidential doodles have been sold at auction. One of Ronald Reagan’s fetched $10,000—pretty good, considering that Picasso’s brought only $40,000. Some celebrities, including presidents, now create doodles expressly for sale at charity benefits—although, to return to Ralph Bunche’s important insight, a doodle drawn with such purposeful intent may not truly deserve the name.26

The commodification of offhand scribblings and similar trivial effects through auctions can strike us as morally dubious. It privatizes what should be public (selling off presidents’ wares to the highest bidder) and publicizes what should be private (putting on display personal drawings or artifacts). But in recent times—the postmodern chapter, if you will, in presidential doodling history—the line between public and private has blurred. Reagan’s sketches, fittingly, embody this confusion. Reagan doodled deliberately for admirers who wrote to him at the White House. His drawings were designed to promote the impression— a contrived one, but not a false one—of a light-hearted president, youthful in spirit, freely and earnestly dashing off drawings for his fans. Reagan was aware of the PR value of these aggressively cute pictures. The White House even compiled some of them for scrapbooks. With doodles, as with so much else for Reagan, the traditional distinction between the real and the image collapses.27

For Reagan, the knowledge that the press and the historical record were looming over his every move presented a political opportunity. For others, it has been an inhibition. After moving into the White House, George W. Bush—wary like his father of public scrutiny—stopped e-mailing his regular cyber-correspondents, fearing that they would be “subject to open records requests.” But no president can keep a hermetic bubble around his personal notes, as Bush found out at the United Nations in September 2005. When nature called during a speech by the leader of Benin, Bush wrote a note to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, as if asking permission from his mother or a teacher: “I think I MAY NEED A BATHROOM break? Is this possible?” Reuters photographer Rick Wilking caught the note on film, to the president’s chagrin. Like true anti-Freudians, administration flacks discouraged journalists from reading too much into the note or its timing. Yet it’s hard not to conclude that the moment Bush chose for his exit may have been influenced, if only unconsciously, by his level of interest in the concerns of the Third World.28

Of course, it’s perfectly fair to say of notes like Bush’s—and of presidential doodles more generally—that they shouldn’t be taken too seriously. But it’s also important to remind ourselves that they shouldn’t be taken too lightly either. Offering glimmers of and glimpses into the private president, doodles constitute small sources of potential understanding to a public that is forever striving to gain insight into its leaders. After all, the meaning of these doodles is in good measure what we make of them—a liberating and democratic realization, and a statement that’s equally true of the American presidency itself.

1 Richard A. Clarke, Against All Enemies: Inside America’s War on Terror (New York: Free Press, 2003), p. 86.

2 Herbert S. Parmet, Eisenhower and the American Crusades (New York: Macmillan, 1972), p. 273; George B. Kistiakowsky, A Scientist at the White House: The Private Diary of President Eisenhower’s Special Assistant for Science and Technology (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1976), p. 149; Peter Edelman, Searching for America’s Heart: RFK and the Renewal of Hope (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001), p. 27.; The New York Times, December 18, 2004, p. 19.

3 Michael Balter, “From a Modern Human’s Brow—or Doodling?” Science, January 11, 2002, pp. 247-248; Matthew Battles, “In Praise of Doodling,” The American Scholar, September 2004, pp. 105-108.

4 George Pendle, “New Foundlands,” Cabinet, Summer 2005, pp. 65-68; “Russell Arundel, 75, Dies, Pepsi Official, Sportsman,” Washington Post, February 3, 1978, C4.

5 Russell M. Arundel, Everybody’s Pixillated: A Book of Doodles (Boston: Little, Brown, 1937), p. ix.

6 W. H. Auden, “In Memory of Sigmund Freud,” in (New York: Random House, 1940);Another Time(New Arundel, passim.

7 Charlotte Kamp, “Doodles Are ‘Self-Portraits,’” New York Times Magazine, June 1, 1947, p. 22; “White House Doodles,” Time, September 6, 1982, p. 80.

8 Norman Uris, The Doodle Book (New York: Macmillan, 1970), p. 72.

9 Uris, pp. 21, 9.

10 “Richard Nixon/Frank Gannon Interviews,” May 13, 1983, 41:31-45:26. Available at http://www.libs.uga.edu/media/collections/nixon/nixonday5.html. Accessed on January 4, 2006.

11 S. Lynn Chiger, “Discover What Your Doodles Say About You,” Mademoiselle, July 1994, p. 144; “Doodles & Squiggles: What They Reveal,” ‘Teen, October 1993, pp. 96-97.

12 Kamp, p. 22.

13 John Rhodehamel, ed., George Washington: Writings (New York: Library of America, 1997), p. 515.

14 Marcus Cunliffe, George Washington: Man and Monument (Boston: Little, Brown, 1958), p. 15.

15 Bruce Miroff, Icons of Democracy: American Leaders As Heroes, Aristocrats, Dissenters, and Democrats (New York: Basic Books, 1993), p. 180.

16 See for example, Fred I. Greenstein, “The Benevolent Leader: Children’s Images of Political Authority,” American Political Science Review (December 1960), pp. 934-943; Greenstein, “More on Children’s Images of the President,” Public Opinion Quarterly (Winter 1961), pp. 648-654; F. Christopher Arterton, “Watergate and Children’s Attitudes Toward Political Authority Revisited,” Political Science Quarterly (Autumn 1975), pp. 477-496; Paul B. Sheatsley and Jacob J. Feldman, “The Assassination of President Kennedy: A Preliminary Report on Public Reactions and Behavior,” Public Opinion Quarterly (Summer 1964), pp. 189-215; John W. Dean, Blind Ambition: The White House Years (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1976), p. 193.

17 Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America and Two Essays on America, (New York: Penguin Books, 2003[1835]), trans. Gerald Bevan, p. 237; M. J. Heale, Presidential Quest: Candidates and Images in American Political Culture, 1787-1852 (New York: Longman, 1982), pp. 51-63.

18 Michael E. McGerr, The Decline of Popular Politics: The American North, 1865-1928 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 174; Charles Ponce de Leon, Self-Exposure: Human Interest Journalism and the Emergence of Celebrity in America, 1890-1940 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), pp. 172-205.

19 Thomas C. Leonard, The Power of the Press: The Birth of American Political Reporting (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), p. 100; “Pampered Pets of Prominent People,” The New York Times Magazine, September 18, 1904, p. 4.

20 Lindsay Rogers, “The House Spokesman,” Virginia Quarterly Review, July 1926, p. 356.

21 Eric Goldman, “Can Public Men Have Private Lives?” The New York Times Magazine, June 16, 1963, p. 13 ff.

22 Michael Duffy, “The Incredible Shrinking Presidency,” Time, June 29, 1992.

23 David Greenberg, Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003), pp. 239-44.

24 Roderick Hart, Seducing America: How Television Charms the Modern Voter (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), pp. 26-32; Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., Kennedy or Nixon: Does It Make Any Difference? (New York: Macmillan, 1960), p. 12.

25 Unidentified newspaper article, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, Herbert Hoover Papers, Post-Presidential Subjects File, Doodles Correspondence 1936–1959.

26 The New York Times, April 24, 1986, B6.

27 Michael J. Sandel, “Bad Bidding,” The New Republic, April 13, 1998, p. 10.

28 The New York Times, March 16, 2001, A5; The Washington Post, September 16, 2005, A29.