ELAINE ELINSON HAD NEVER VISITED the headquarters of the United Farm Workers union, nor had she ever met the president of the organization, Cesar Chavez, despite having served in the movement for more than a year. Yet in 1969, as soon as she stepped onto the stage at Filipino Hall in Delano, California, the mostly Mexican and Filipino audience greeted her as a long-lost sister. Farm workers and activists alike honored her with the traditional farm worker “clap” that started slowly and built rapidly to a crescendo and cheers of “Viva la Huelga.” Elinson, like many boycott workers, had skipped a process of initiation in the trenches of the grape strike in favor of serving where she was needed most: on the front lines of the consumer boycott in urban centers around the world. For her, the notion of an international boycott became a reality on the docks and in the union halls of London, Copenhagen, and Stockholm, where she combined asking consumers not to buy grapes with the more traditional appeal to fellow unionized dock workers not to unload them. She recounted her experience that evening in Delano after the long battle abroad:

And as I stood there before this huge, curious, and open-hearted crowd, I realized I was one of the luckiest people in the world. I had been the link between the courageous, tenacious, spirited farm workers of the UFW and the committed, internationally minded transport workers of Britain and Scandinavia. Though they didn’t know each other, they were ready to fight together for La Causa. Together, they had pulled off an amazing feat of solidarity. The cheers that I heard in the Filipino Hall mixed with the cheers I had heard on the docks at Tilbury, Malmo, Birmingham, and Liverpool. So this is what they mean by “Workers of the World, Unite!”1

Relying on a London pay phone and the advice of the boycott coordinator Jerry Brown, Elinson had stopped grapes from reaching the European market. For those on the ground in Delano, this achievement earned her a degree of respect equal to workers and picketers in the fields and in front of markets in the United States. Her success proved to the faithful in the movement that consumers and workers around the world had the capacity to care for farm workers in rural California.

Events in Europe also provided evidence that the union’s investment in the boycott at midharvest 1968 had been a wise one. Growers disputed the effectiveness, but the shift in sales of table grapes away from traditional markets to smaller cities, rural areas, and overseas signaled an industry in crisis. Table grape growers repeatedly pointed to the increases in their production—up 19 percent in 1969 from 1966 totals—while ignoring the fact that use of these grapes for table consumption had declined by 12 percent. Increasingly, growers designated grapes for crushing to salvage any value from their crops.2 The Grape & Tree Fruit League attempted to disguise losses in sales of the popular Thompson seedless grapes by announcing the record sales of other varieties, while ignoring that growers earned between 50 cents and a dollar less per box than in 1968. Such media efforts failed as desperate Coachella growers, dependent on the substantial profit margins created by being the first on the market, publicly disputed the rosy picture painted by the league. Among them, Lionel Steinberg, owner of the David Freedman Ranch, worried aloud about falling grape prices, rising production costs, and the declines in Thompson sales that threatened to put him out of business. “We are not selling in normal quantities in major markets such as Chicago and New York,” Steinberg complained, “and prices for Thompson seedless grapes have already broken and are down to $5 a box, compared to about $6.50 last year.” Predicting, “Many of us will show red ink this year,” Steinberg’s admissions disclosed two uncomfortable truths: the UFW was winning, and the growers lacked the power to stop it.3

The substantive data flowing from the nerve center of the boycott confirmed the momentum experienced in the field. Whereas Brown and LeRoy Chatfield had established the goal of having effective boycott houses in ten of the forty-one leading cities, by early 1969 the union had established boycott houses in thirty-one cities and was about to open new ones in the South and Mountain West, places formerly thought to be impervious to farm worker appeals. In the traditional markets, organizers stepped up their efforts to overcome impediments to the boycott, while news of their success encouraged volunteers elsewhere to implement boycotts of table grapes in their cities. Through it all the UFW maintained no budget for publicity, relying exclusively on coverage from eager journalists.

Yet despite this success, the union struggled to make ends meet. Beleaguered growers maintained the economic advantage by hiring a San Francisco–based public relations firm, Whitaker and Baxter, to counter union claims of worker exploitation and pesticide use.4 Members of the South Central Growers Association also began to see beyond their ethnic divisions to organize twenty-six growers into a new coalition. The growers’ group secretly financed the Agricultural Workers Freedom to Work Association, a parallel labor organization that failed to attract meaningful support among workers. The UFW quickened AWFWA’s demise by exposing the organization’s general secretary, Jose Mendoza, as an anti-Chavez labor contractor on the growers’ payroll.5 Still, countering the growers’ moves depleted resources as the union stretched its budget to meet the commitments made to the boycott during the July 1968 retreat. Chavez, who privately worried about “the tremendous drain on the [union’s] treasury,” saw 1969 as a critical year to the overall success of the movement. “At this point,” he told Ganz as the union prepared for its fourth and most serious year of the boycott, “it’s either them or us.”6

SUCCESS IN NORTH AMERICA

The game plan prepared by Jerry Brown and LeRoy Chatfield produced results as boycotters returned to houses across the country for the remainder of the 1968 season and through the 1969 harvest. Chatfield, for example, adapted to the conservative environment of Southern California. In October 1968, seventeen Los Angeles stores, led by Safeway, successfully sued to limit to four the number of picketers outside the entrance of their markets. Rather than resist the new laws with civil disobedience and boisterous protests, Chatfield chose a more labor-intensive approach that involved well-dressed union representatives working ten hours a day, six days a week. Each representative adopted a calm, business-like demeanor and made appeals to shoppers on an individual basis. Chatfield recruited sixty new, full-time volunteers and concentrated their efforts on thirty stores in the Arden-Mayfair chain, a major competitor of Safeway. “It was grueling work, but it did the trick,” Chatfield reported to Brown. “At first, people didn’t pay much attention to us. But after they saw us several times, they’d stop to talk. Eventually, many of them agreed to shop elsewhere. The ones who did really understood the issue and would often talk to the manager and tell him why they were switching to another store.”7 By the end of the 1969 harvest, Chatfield’s tactics had succeeded in convincing Arden-Mayfair to remove table grapes from their stores. Although Los Angeles continued to be a challenge, the boycott reduced overall shipments to the second largest market for table grapes in the United States by a respectable 16 percent.8

The boycott swept over the continent, garnering support from consumers and politicians alike. In Toronto, the mayor declared November 23, 1968, “Grape Day” and announced the city government’s decision not to buy grapes in recognition of the farm workers’ struggle. In Chicago, Eliseo Medina organized a boycott campaign that persuaded the leading supermarket chain, Jewel, to stop carrying table grapes at every one of its 254 store locations. For this feat, Mayor Richard Daley, a pro-labor Democrat, recognized Medina as “Man of the Year” and endorsed the boycott. Similarly, in Cleveland, Mayor Carl Burton Stokes, the first African American to be elected mayor of a major U.S. city, ordered all government facilities to cease serving table grapes. Mack Lyons, the only African American on the National Executive Board of the UFW, made the appeal to Stokes and organized one of the strongest boycott houses in the network. In San Francisco, five major agribusiness organizations canceled their annual meetings in the city in response to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors’ endorsement of the boycott. At the annual meeting of the National League of Cities, the mayor of Delano, Clifford Loader, tried to stem the tide of city governments’ support for the boycott by introducing a resolution requesting mayors not to take sides in the grape dispute. To Loader’s dismay, his peers soundly defeated his proposal.9

Support from religious leaders extended the appeal of the boycott to patrons ordinarily more reluctant to weigh in on labor matters. From the beginning individuals from a range of organized religions supported the movement, volunteering their time to the union, occasionally in defiance of their church’s orders. By 1968, however, organized religion began to see the moral dimensions behind the farm workers’ modest demand for collective bargaining. That growers resisted this basic right shared by many working-class churchgoers permitted men of the cloth to take a position in favor of the union.

New reports of farm workers suffering from exposure to pesticides also moved religious and secular consumers alike. Jessica Govea, working in the new union Service Center, received complaints from many women who experienced dizziness, nausea, and sweats after working in the fields. As a former field worker in Bakersfield, she knew the symptoms associated with exposure to pesticides and immediately appealed to Jerry Cohen to see what could be done about the problem. When Cohen asked the agricultural commissioner, C. Seldon Morely, for reports of pesticides use on grapes, the growers went to the courts to block access. When the matter finally made it to a Kern County court, the judge blocked access to the records on the grounds that the union would use it in the boycott. Eventually, Cohen succeeded in winning access to several “little green booklets” listing the days in which growers sprayed, but limited information on what exactly had been used. The lack of clarity on the subject inspired the union and Senator Walter Mondale, a Democrat, to aggressively pursue a farm worker’s right to know the contents of the pesticides, and provided boycott volunteers another talking point on the picket lines.10

The momentum of the boycott carried it north, where shipments of California table grapes arrived at a fruit terminal in Detroit before being distributed throughout Michigan, Ohio, and Canada. The UFW initially tried to shut off the corridor by targeting the fruit terminals run by a director known only as “Mr. Andrews.” During the 1968 campaign, the Detroit boycott house, managed by a Catholic nun, Sister Lupé Anguiano, and an L.A. boycott veteran, José Serda, appealed to Andrews to cooperate with the boycott, but the terminal director showed little regard for the union. Appearing to have reached a dead end in Detroit, Chavez shuffled the leadership by bringing in Hijinio Rangel to run the house.

Rangel moved his entire family to the Motor City from Portland, Oregon, in December 1968. Within a few weeks, the Rangels mobilized a group of 5,000 volunteers composed of students, religious leaders, and fellow unionists to march from Ann Arbor to Detroit. The former Delano labor contractor and tortilleria owner followed this show of force with quiet but persistent appeals to Andrews to rethink his opposition to the boycott. As Rangel recalled in his memoir, Andrews responded with disdain, boasting, “I sent José Serda and Lupé Anguiano back to California, and the same is going to happen to you. You will go back on your knees.”11

Rangel accepted the insult as a challenge to devise a successful strategy. Rather than continue his appeals to Andrews, he took his case to Detroit’s leading supermarket chain, Kroger’s. Flanked by nuns on one side and a priest on the other, Rangel asked store managers not to carry California table grapes. When these efforts failed, he directed volunteers to enter the markets with their protest, provoking managers to call the police to arrest them. As protesters filled the city jail to capacity, court officials quickly arranged arraignment hearings on a Saturday to deal with the deluge of cases. Rangel recalled, “[The] judge arrived still in his shorts because he had been cutting his lawn.” In advance, Rangel made contact with local leaders in the AFL-CIO, UAW, and steelworkers, carpenters, and electrical workers unions, who lent their legal counsel to the boycotters in their moment of need. As the courtroom filled with more than a thousand arrested protesters, the judge dismissed the charges and sent UFW volunteers flowing triumphantly into the streets of Detroit. On Monday morning, Kroger’s acquiesced and announced its decision to stop selling grapes at all of its twenty-five Detroit-area locations. Rangel complemented these actions by engaging in an eleven-day public fast to draw attention to two other markets, AM-PM and Farmer John’s, both of which eventually fell into line with the boycott.

The campaign against Detroit-area markets did not immediately break Andrews, given that the fruit terminal served as a transfer point for table grapes going to markets beyond the city. Rangel ordered 150 volunteers to picket the terminal around the clock and sent another 500 to picket independent stores still receiving table grapes. Picketers met Andrews every morning at seven, first in front of the terminal as he came in for work, then quickly moving to his office to create the illusion that the union had 300 boycotters working the picket lines. On the ninth day, Andrews agreed to negotiate, offering to discontinue the sale of California grapes after the arrival of the last trainload. Rangel recalled the conversation: “I said, ‘This is not acceptable, Mr. Andrews. Send a telegram to Mr. Giumarra requesting he take the grapes back. I want a copy of the telegram. Also I want permission to inspect your terminal every day until further orders.’” A beleaguered Andrews conceded to Rangel’s demands and stopped selling grapes immediately. A few days later, when Rangel sent his son, Manuel, to inspect the terminal, Andrews asked the young man to convey a message: “Tell your father that I have much respect for him.”12

The success of the boycott significantly disrupted the grower community as differences among them became more pronounced the longer the boycott wore on. Coachella growers, who had a reduced capacity to withstand the pressures of the boycott given the shortness of their growing season, felt the pinch earlier and more acutely than their San Joaquin Valley peers. They increasingly resented the messages from the Grape & Tree Fruit League that growers were impervious to the boycott. Lionel Steinberg, the unofficial spokesperson for Coachella growers, broke with the league’s practice of focusing on production totals from one year to the next by making broader and longer range comparisons that took into account production costs and consumer spending on groceries. For Steinberg, the differences between 1952, when consumers spent 30 percent of their income on food, and 1969, when they spent only 17 percent, provided a more accurate portrait of the changes in the market. The doubling of wages from $1 to $2, increases in the cost of containers from 25 cents to 70 cents, and the cost of tractors up from $1,800 to $6,000 over this same period gave them reason to worry. The prospect of losing 20 percent of their market to the boycott weighed heavily on Steinberg and other Coachella growers who had had enough by 1969. “Farm workers and growers both have problems,” he opined, “and it does not do any good to try to fool anyone about the additional problems presented to growers by the boycott.”13

Steinberg responded to these conditions by resigning from the Grape & Tree Fruit League and organizing ten of his fellow Coachella growers to sue for peace with the union. In his letter of resignation, Steinberg accused E. Allen Mills, the league’s executive vice president, of sweeping the problem of the boycott under the rug. “When you keep insisting everything is rosy and we should keep our chins up,” Steinberg angrily wrote, “I sincerely feel you are doing a disservice to the growers.” Steinberg now laid bare to the public a rift within the industry. San Joaquin Valley growers viewed Coachella as a relative newcomer to the business, constituting only 10 percent of the total market for grapes. Steinberg, an entrepreneur who had invested in farmland after the arrival of federal water in 1948, stood outside a well-developed grower culture in the San Joaquin Valley. Although Marshall Ganz thought it more than a coincidence that Jewish owners of farms were often the first to settle disputes with the union, the breakdown in the grower coalition during the 1969 harvest appeared to have more to do with market share and regional differences among California growers than with anti-Semitism.14

Trying to work out a settlement with the union proved to be as difficult for Coachella growers as getting their San Joaquin peers to care about them. Caught up in the momentum of the boycott, union officials pushed hard once they arrived at the negotiation table. The union’s delegation, which many growers deemed “the circus,” offended the majority of Coachella growers, who abandoned Steinberg and vowed to fight on. A year later, Monsignor George Higgins of the National Catholic Conference reported the sentiments of the growers in the aftermath of the failed negotiations: “They said the union had 20 or 30 people in the room, workers and what not. They said the union didn’t negotiate; it made demands.” Whether the UFW overplayed its hand mattered less than that the union had opened up yet another schism among the growers.

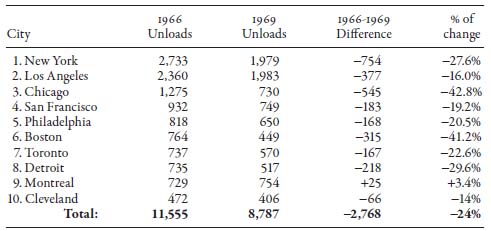

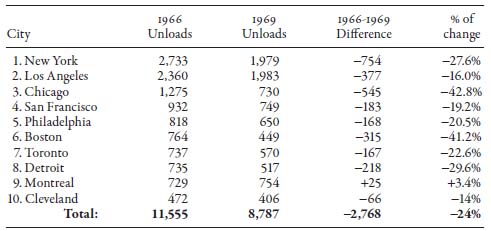

The absence of a settlement with Coachella growers did little to dampen Chavez’s excitement for the boycott. By the end of the 1969 season, the union had achieved most of the goals set during the summer retreat a year before, namely the organization of effective boycott houses and the reduction of table grape sales in nine of the ten most important cities in North America. The union relied on two sources of information that indicated progress: the reports flowing from the boycott houses to Jerry and Juanita Brown and the hard evidence present in USDA reports regarding the changes in grape sales from year to year. The poor growing conditions in 1967 that led to unusually low crop yields caused the union, growers, and the government officials to rely on 1966 as the more appropriate benchmark for the 1969 season. USDA reports confirmed Steinberg’s complaints and the unions’ claims of progress. Shippers posted a decline of 24 percent in grape shipments to the ten leading cities and provided evidence of extremely effective boycott operations in Chicago (down 42.8 percent), Boston (down 41.8 percent), Detroit (29.6 percent), and New York City (27.6 percent). In fact, only one city among the top ten, Montreal, posted an increase in car lots of California and Arizona table grapes from 1966 to 1969, whereas the other nine major boycott houses hit their target of reducing shipments by 10 percent or more.

Growers attempted to circumvent the boycott by redirecting table grapes to other major North American cities, especially those in the South, including Atlanta, Memphis, Miami, and New Orleans. The UFW built new boycott houses in thirty-one of these cities to meet the challenge, including twenty-one supported by a paid organizer and the other ten staffed entirely by volunteers. Among these houses, the twenty-one with paid organizers reduced shipments by 13 percent, whereas the ten with no organizers still managed to reduce shipments by 12.6 percent. Growers also experienced a dramatic decline in profits as the glut of unsold grapes on the market forced brokers to lower the prices to offload their inventory. These declines hurt Coachella growers the most because their profits depended on the bump in prices that accompanied being the first on the market. By placing their grapes in cold storage in anticipation of finding new markets, Coachella growers experienced more competition and lower prices as the season wore on and San Joaquin Valley table grapes became available. In a market made uncertain by the boycott, grape growers could anticipate a poorer return on their investments.

TABLE 1. Car Lot Unloads of All California and Arizona Table Grapes in Ten Major North American Markets, 1966 and 1969 Seasons Compared*

SOURCE: Compiled from U.S. Department of Agriculture, Consumer and Marketing Services, Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Unloads in Eastern, Southern, Midwestern and Western Cities by Commodities, States and Months, 1966, 1967, 1969, 1970, passim. In Jerald Barry Brown, “The United Farm Workers Grape Strike and Boycott, 1965-1970: An Evaluation of the Culture of Poverty Theory,” (Ph.D. dissertation, Anthropology, Cornell University, 1972) 212.

*May through January shipments

The enthusiasm of volunteers to staff more effective boycott houses and the mostly sympathetic press coverage the union received convinced Cesar Chavez of the centrality of the boycott to the movement. Over a four-year period, the boycott moved from an activity undertaken by the union to keep farm workers and volunteers inspired between harvests to a year-round tactic. According to Jerry Brown, when farm workers from other crops and workers from Oregon, Texas, Florida, and Ohio appealed to the UFW to send organizers, Chavez declined such invitations not only because the union had been stretched to its limits, but also because he now believed it would be “foolish” to initiate a strike without the backing of a boycott.15

Growers refused to concede defeat, however, believing that their tactic of shifting sales to underdeveloped markets had not been fully explored. As bad as USDA shipment reports for traditional markets appeared, growers succeeded in rerouting one-third of their shipments to rural areas and smaller cities where the UFW had no representatives. The diverted shipments amounted to a 20 percent increase in these areas, which left growers’ total shipments for the entire North American market down by 9.2 percent for the year. Given their ability to adjust to the adversities caused by the boycott, most growers held on to the idea that an organized rerouting and strategic marketing of grapes could wear down the union. Moreover, the failure of the UFW to create a viable boycott in Montreal suggested the possibility of beating the union in the international marketplace, where cultural distinctions and different labor and picketing laws made it more difficult for the union to establish effective boycott houses. By moving grapes across borders and off-shore growers hoped to finally expand beyond the reach of the UFW and break free of the power of the boycott.

THE INTERNATIONAL ARENA

Across the Detroit River in Canada, Marshall Ganz and Jessica Govea worked to consolidate the gains made in the United States by enforcing the boycott in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec. Although laws restricted the union from staging storefront protests, Ganz’s uses of creative nonviolence played on the sympathies of customers. The enthusiasm of local volunteers affirmed the beliefs of the Toronto boycott staff, as did the support from Canadian unions and the decidedly favorable coverage by Toronto media. These attitudes reflected not only the presence of a strong pro-labor sentiment among Toronto residents, but also the ability of boycott workers to communicate the stakes in the grape strike taking place in the fields of California. That both boycott house workers and residents of Toronto spoke English was significant, allowing them to speak a common language—literally and figuratively—when it came to discussions about workers’ rights.

During the 1969 season, Govea worked with Ganz to organize the entire Canadian campaign from the Toronto office.16 Born in Bakersfield, California, into a farm-working family, she spent every summer from the age of four to fifteen picking cotton, grapes, and plums in the San Joaquin Valley. Her father routinely demonstrated against grower injustice toward workers and inspired the young Govea to organize farm worker children to petition and protest for change. In 1966, she left college to work for the UFW in Delano, then accepted an assignment from Chavez in July 1968 to join Ganz in Toronto. The two worked well together and over time developed a personal and professional relationship bound by their service to la causa.

In addition to Govea and Ganz, the Toronto staff included Mark Day, Hub Segur, and Jim Brophy from the United States, and Linda Gerard and Keith Patinson, both natives of Canada. Gerard came by way of a “donation” from the UAW regional office in Windsor, where the twenty-one-year-old secretary had served the union for the previous two years. The UAW continued to pay her full-time salary, while the union covered the cost of her food and paid her the usual $5 per week allotted to every volunteer. Patinson also served the boycott full time at the will of the UAW, which covered all of his expenses. In addition, the Delano office assigned Mike Milo to work out of Windsor, to organize “secondary Ontario cities,” although eventually Ganz incorporated him into the Toronto house to centralize his staff.17

FIGURE 8. Supporters of the grape boycott demonstrate in Toronto, December 1968. Jessica Govea is in the center, front row (wearing poncho). ALUA, UFW Collection, 303.

The growth of the Canadian campaign through the summer and fall of 1969 required the union to split up Govea and Ganz for strategic purposes, placing Govea in Montreal while Ganz remained in Toronto to build on his success. At the end of 1969, Chavez expressed a desire to have Ganz and Govea return to Delano in case growers again showed interest in negotiating a settlement with the union. Ganz’s success in convincing all but one of the presidents of Toronto’s grocery chains (Leon Weinstein of Loblaw’s) to discontinue sales of California grapes distinguished him as a talented negotiator; Chavez valued Govea for her authentic voice that lent credibility to any potential negotiating team. The importance of the Canadian boycott, however, forced Chavez to delay their return until their presence was absolutely necessary.18

Throughout 1969, Govea and Ganz concentrated on creating a national campaign, organizing volunteers, arranging conferences, and reporting on the progress of the boycott well beyond their base in Ontario (Toronto, Windsor, and Ottawa) and Quebec (Montreal) to the northeast, and cities to the west in the provinces of Manitoba (Winnipeg), Saskatchewan (Saskatoon, Regina), Alberta (Calgary, Edmonton), and British Columbia (Vancouver). In the central and western provinces, Ganz relied on volunteers to staff boycott houses, while he and Govea coordinated with allies from the Canadian labor movement to generate support for the boycott. One of the union’s staunchest foes, Safeway, dominated the grocery store landscape in the West, making the fight even more difficult. Still, Ganz reported progress in Winnipeg and Manitoba, where strong boycott committees picketed stores and the provincial governments agreed to halt the purchase of table grapes.19

Ganz and Govea focused most of their attention on Windsor, Toronto, and Ottawa in Ontario and Montreal in Quebec, but the distance and cultural differences between the two regions made operations difficult. When the two attempted to bring together volunteers from Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal for an annual weekend planning conference in a central location, Ganz found it “not really practical because of tremendous differences in Ontario and Québec and the distances involved.” A seven-hour drive separated Toronto and Montreal, a distance not easily bridged until the boycott house purchased a second car, a 1966 Ford Galaxy, for $1,000 with the help of a dealer in Detroit and money donated from the Canadian Labour Congress, the UAW, and the steelworkers union.

The expense of maintaining contact over such great distances perpetually challenged the boycott house and made money a constant concern for the organizers. “Our budget of $590.00,” Ganz wrote Juanita Brown in January 1970, “was predicated on two full-time people at the time it was drawn up.” Although the amount constituted a significant sum for the union, their overwhelming success at recruiting local volunteers generated new expenses, including food and a weekly stipend of $5 per volunteer that stretched the annual budget beyond its limits. The house also had to pay for rent increases, phone bills, and office expenses, including gas, often on one union credit card passed from volunteer to volunteer. Although these problems confronted every boycott house, the exchange rate and the miles the Toronto house volunteers had to cover and the cost of long-distance and international phone calls complicated their situation. “Jessica wrote repeatedly asking that a budget adjustment be made,” Ganz wrote, “[but] it was never made.” As a consequence, the house lost volunteers when Ganz, Segur, and Govea returned to Delano between seasons.20 Ganz recommended the creation of a full-time staff in Toronto and suggested moving Govea to Montreal long enough to remedy the situation. He also recommended funds to support a separate office in Ottawa, about five hours away, but the request exceeded the capacity of the union to pay for it. “The whole Canadian [boycott] is about a year behind the major American cities,” Ganz reported, but he believed such changes would produce a campaign “stronger than ever this year.”21

In spite of their late start, Ganz’s work with Steinberg’s and Dominion in 1969 laid an important foundation for the house to build on in the winter of 1969 and the spring and summer of 1970. Loblaw’s remained the only holdout, which allowed volunteers to concentrate on it. Ganz and Govea made a concerted effort to strengthen their relationship with supporters in the Canadian labor movement and the Canadian government. The endorsement of the Canadian Labour Congress contributed not only good publicity to the boycott, but also local union members who staffed picket lines in the toughest of conditions. Beginning on December 20, in the midst of a typical Toronto winter with temperatures falling to 2 degrees, more than three hundred volunteers participated in a five-day, 110-hour continuous vigil in front of Loblaw’s largest downtown location. Volunteers, local aldermen, and members of the provincial parliament sang Christmas carols, staged candlelight processions, and held an ecumenical midnight Christmas mass while Ganz and five others fasted in solidarity with strikers in California. Boycott organizers also targeted professional athletes and sporting events, such as the Toronto Maple Leafs’ hockey games, which drew 16,000 people two nights a week. The house printed thousands of leaflets with a lineup of the teams and special commendations to those stars who endorsed the boycott. “Passed out 6,000 leaflets in about 35 minutes,” Ganz reported to Delano. At the games, volunteers collected signatures on a petition asking Loblaw’s to stop selling grapes.

The effectiveness of the boycott through the 1969–70 winter produced concern among Coachella growers who, once again, desired to settle the strike in advance of the upcoming table grape season. In anticipation of negotiations, Ganz moved back to Delano. Meanwhile, Jerry and Juanita Browns’ move to Toronto supplied the Canadian campaign with two proven leaders to sustain the momentum while Ganz was away.22

Upon their arrival, Manny Rivera and the Browns made contact with Loblaw’s owner, Leon Weinstein, who invited the leaders and Manny’s wife and three children to his office. Born in the back of his father’s neighborhood grocery store in Toronto, Weinstein had taken over the family business as an adult and expanded it into a successful chain built primarily on good customer relations. Although politically conservative, Weinstein prided himself as a fair-minded entrepreneur with the power to disarm those who questioned his business practices. Jerry Brown recalled, “He [told] us how he would not have grapes in his home, how he supports the farm workers’ cause, but he is the president of a large chain, and the consumers have to have free choice, so he cannot publicly support the boycott.” Weinstein also made a peace offering of Cuban cigars to Rivera, who accepted the gift and came ready to reciprocate. “He hand[ed] Leon a farm worker calendar,” Brown remembered, “every month of which ha[d] a picture of the travails in the fields—you know, hungry children, child labor, tired workers.” “I’m going to give you … our calendar,” Rivera told Weinstein, “and I hope you’ll put it on the wall, so that every day you look at it, you’ll be reminded of the suffering you’re causing our people by carrying grapes in your store.”23

A few days after the meeting, Mrs. Rivera found out about a Loblaw’s party at which Weinstein would be honored for his leadership of the company. Typically, the house would picket such an event, but this time Mrs. Rivera proposed something different: “We’re going to turn this into a funeral procession.” For the night of the celebration, the union created cards that, at first glance, appeared to be a program for the evening. Once guests opened the cards, however, they discovered information about the unfair labor practices of grape growers and their use of pesticides in the fields. Volunteers also brought to the event makeshift caskets made of used grape cartons covered in black paper and photos of farm workers toiling in the fields. The union recruited several priests and nuns to accompany them to the event, creating a public relations nightmare for Weinstein. Brown remembered, “He almost broke out into tears at the celebration.” Two weeks later, Weinstein announced his decision to remove table grapes from all twenty-six Loblaw’s locations and resigned from the company.24

In Montreal, Jessica Govea worked to replicate the success in Toronto. In January, Ganz wrote of Montreal, “We have not had a particularly effective boycott here.” He attributed the problems to three causes: “1) lack of effective organizing work; 2) lack of French-speaking staff; 3) the nature of Quebec itself.” Govea’s move to the city on a full-time basis helped turn the situation around. She began by recruiting a staff with some capacity to speak French, including Peter Standish, a twenty-something who had served in the highly successful New York City boycott house during the 1969 season.25 A visit by Cesar Chavez in late 1969 lent legitimacy to the movement in the province and gave Govea a foundation for coordinating with local unions. She cultivated a relationship with Louis LaBerge, president of the Québec Federation of Labour, and worked with the farmers union in Quebec, L’union de Cultivateurs Catolique, which publicly endorsed the boycott.26

Yet for all her efforts, the creation of an effective boycott equivalent to those in other cities eluded Govea. The union’s appeal to a society embroiled in a secessionist crisis made the boycott, at best, a secondary consideration. For many Québécois, the embrace of the boycott by English-speaking Ontario made the movement suspect. “Not only is the boycott an ‘American issue,’” Ganz wrote Larry Itliong, “but we have to deal with a foreign country in a foreign language, which makes the boycott doubly distant.” The difference in reception from English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians was manifested most acutely in the varying level of support the union received from organized labor. “We are particularly concerned about the fact that we are not getting the kind of co-operation that we need from the two Quebec labour movements,” Ganz wrote. “It is a bit as if the Quebec apple pickers were on strike and sent a representative to Delano and expected us to go all out [on] behalf of their problem.” In spite of Govea’s relations with LaBerge, he withheld his endorsement of the boycott until Chavez requested it.27

Govea appreciated Chavez’s assistance, but the need for “man-to-man” communication to gain the respect of a fellow unionist must have rankled her. In addition to her frustration with LaBerge, she tussled with the younger Standish, who challenged her authority within the Montreal boycott house. Although Standish had worked under Dolores Huerta in New York City and lauded her leadership, he demonstrated a lack of respect for Govea and undermined her leadership by questioning her strategies, maligning her organizational skills, and engaging in tonterías (stupid behavior) that influenced the morale of the house. In a letter to Chavez, Govea explained that Standish had come to Montreal with the expectation that he would be put in charge of the house. When that did not happen, he began to work behind Govea’s back to undermine her credibility with the staff. Govea’s meetings with Standish confirmed her impressions but also revealed a level of disrespect reserved especially for her. “He also believes that I am extremely incompetent,” Govea disclosed to Chavez, “[and] that if he could go to a city where there was someone like Gilbert Padilla or someone important like that, then he would.” Standish gave Govea the impression he was telling her, “You go, or I go,” a sentiment she deeply resented and equated to blackmail. Ultimately, she recommended that Chavez not give in to Standish’s wishes: “Either he stays here where he is needed and works well with this group, or he goes [leaves the union] altogether.”28

Standish, in fact, did circumvent the chain of command by writing to Chavez directly, requesting a transfer and telling his side of the story. For him, the question came down to a personality conflict and contrasting philosophies of organizing. He objected to Govea’s attitude toward him, which he saw as “increasingly defensive and combative.” Undoubtedly, Standish’s organizing against Govea influenced the tenor of her communication with him, yet his own “ghastly feeling” that he was being “horribly under-used” smacked of arrogance and even insubordination. Moreover, Standish openly expressed hostility toward the “shop-in” used to great effect by Huerta in New York City and Ganz in Toronto because it promoted “an element of play-acting or pretense, which is repugnant to me.” He objected to the insincerity of the act and worried that if the boycott house ever faced severe internal crisis, members would not trust each other in their attempts to resolve differences. Oddly, Standish advocated a “top down” approach in which the house leader instructed volunteers to stay focused on recruiting customers one shopper at a time, asking them to keep their receipts from markets not carrying table grapes, and sending them to managers of stores that did. Although Standish credited Govea with inventing the “receipt-saving campaign,” he faulted her for not following through on it. “If well carried out,” he wrote Chavez, “it could enable the boycott to sink its roots quite deeply into the population of a city, and could get thousands of people more concretely and directly involved than if they simply signed a pledge not to buy scab grapes and not to shop in stores which sell them.”29 He asked Chavez to consider moving him to Cleveland to replace Dixie Lee Fisher, who, it was rumored, wanted to return to school full time.30

The lack of results in Montreal pointed to weaknesses in the campaign that Standish sensed and both Ganz and Govea admitted. Standish’s observations, however, discounted the complexities of organizing in a foreign country and missed the trial-and-error process used by even the most successful leaders. In Los Angeles, for example, LeRoy Chatfield had to employ both raucous demonstrations and painstaking appeals to customers before learning that the latter worked better in a conservative climate. An underlying conservativism and anti-union sentiment did not shape the attitudes of Montreal shoppers; indeed, Quebec, like Canada as a whole, was more pro-union than most of the United States in 1970. Rather, the union had to overcome not only language barriers but also cultural differences inflamed by the UFW’s early coordination with English-speaking unionists in Ontario. Govea employed a range of tactics in Montreal and worked to build personal relationships with labor leaders, an approach that Standish neither appreciated nor excelled at. Ganz, in his assessment of Standish’s strengths and weaknesses, characterized his approach as “very systematic and organized” and credited him with speaking excellent French, but faulted him for his “lack of experience [in] working with organized groups, especially labour.” Standish’s proposed solution to Montreal’s problems mirrored the disciplined and patient approach taken in Los Angeles; however, by 1970, the union felt the pressure to produce results more quickly as expenses mounted on both sides, and some growers again sought resolution to the conflict.

Standish’s impatience with Govea also signaled the unique difficulties women faced as leaders during late 1960s and 1970s. For example, Govea took exception to Standish’s preference to work with other men or on his own. She told Chavez, “Feelings with respect to titles and importance are his, not mine.”31 Standish made known to both Govea and Chavez his ambition to pursue community organizing as a career. He wrote to Chavez, “I was initially attracted to the struggle by my desire to learn to organize under your leadership so that I could prepare myself to participate in other non-violent struggles which I believe will have to be organized in America.”32 That these skills could be acquired only through mentorship from Chavez and Padilla, or that his break as a leader would come at the expense of a woman—either Govea in Montreal or Dixie Lee Fisher in Cleveland—apparently did not trouble him. Govea refused to accept his behavior, first calling him to a face-to-face meeting to reprimand him. When this failed, she used her clout with Chavez and her authority as the house leader to recommend drawing Standish into line or cutting him loose. Although the record does not show how Chavez responded, Govea’s insistence that Standish remain in the boycott house as a dutiful member under her demonstrated her determination to receive respect on a par with male leaders in the movement.

No story better illustrates the challenges and triumphs that women in the boycott experienced than Elaine Elinson’s. As an undergraduate student at Cornell University in the mid-1960s, Elinson served on the boycott in New York City during summers between her job at the Natural History Museum and acting in “off-off-Broadway” plays. In time, her service expanded well beyond a part-time commitment in Manhattan to a consequential piece of the worldwide boycott puzzle.

Elinson’s background as the granddaughter of Russian Jewish immigrants predisposed her to serve a movement on behalf of immigrant workers. “I was told never to cross a picket line,” she remembered, “and that all people are equal.” Her grandmother came to the United States in 1905, but returned to Russia in 1911 to participate in the Russian Revolution. Elinson remembered her grandmother as a very political person whose grandparents shipped her back to the United States in 1916 to save her life. According to Elinson, her grandmother never fully got over leaving Russia before the 1917 Revolution: “She said, ‘All my friends had gotten killed, I was so depressed … I could have killed myself.’” Elinson’s father reinforced these politics as a professor of public health who looked beyond medicine to social factors such as racism and poverty as reasons for illness among people of color.

Her family cultivated a strong sense of social justice, which manifested itself early in her life. During a trip across country at the age of twelve, she remembered being kicked out of the Alamo for objecting to the sale of Confederate flags in the gift shop. “The woman said, ‘If you don’t like it, you can just leave.’ And I said, ‘Well, I’m trying to leave, but this state is so big, I can’t get out of it!’” After graduating from high school in New Jersey in 1964, Elinson attended Smith College, but the elitism of the school troubled her family. In a questionnaire distributed to all incoming freshman, the college wanted to know, “Will you need a place for your horse?” Elinson recalled, “My dad [said], ‘Oh my God, where are we sending you?’” When some of her classmates took exception to her dating an African American student from Amherst, Elinson sought a transfer to Cornell, a bigger school with a more diverse student body and a wider range of studies.

At Cornell, she studied abroad in the Philippines and pursued a major in Asian studies and Chinese, but also traveled to Honduras to teach literacy and build schools. In general, Cornell provided a broad spectrum of opinions and experiences, including those from the antiwar movement. She considered membership in Students for a Democratic Society, but ultimately found the organization too “white male dominated.” The UFW had much greater appeal because of the bold leadership of Dolores Huerta, whose success in New York she discovered while serving on UFW picket lines and participating in the successful boycott campaign of 1967. During her first year in the movement, Elinson never met Huerta but saw the reverence fellow volunteers had for her: “Dolores was like the great mother of that house on Eighty-sixth Street.”33 When she graduated in 1968, Elinson considered becoming a full-time organizer for the union, but she remained conflicted about pursuing a career as a professor or committing herself to activism. She ultimately decided to serve the boycott house in New York during the summer of 1968 before moving to London to start a graduate program at the School of Oriental and African Studies in the fall.34

The contrasts between the two experiences could not have been more decisive in determining the course of Elinson’s life. The solitude of research in London made her feel somewhat removed from the major conflicts of the day. “I’m sitting in the basement of the British Museum copying characters off Ming dynasty vases,” she recalled, “and [I was] thinking, the Vietnam War is raging, and what am I doing this for?” When she wrote Jerry Brown in Delano to see if she could come back to the United States to work for the union, Brown instructed her to remain in England. By 1968 the growers had begun to transfer shipments overseas in an attempt to circumvent the boycott in North America. “If necessary you could come back right away,” Brown told her, but added, “In as much as you are in London and we are trying to internationalize the boycott, Cesar asked if you couldn’t hold on to your means of existence and do some ground work for us there.”35 Although he knew it would be a long shot, Brown realized that keeping Elinson overseas gave the union a chance to establish its presence in Europe and put the growers’ on notice that the UFW could move with the grapes.

Given the size of the boycott effort, Elinson did not initially stand out for Brown until he saw a photo of her in a file of potential volunteers in Delano. He remembered his reaction: “I saw that she was this cute girl in a mini-skirt with those big glasses that were so popular, kind of Jimi Hendrix glasses … and I said, ‘This girl is perfect for the longshoremen.’” In a letter to Elinson instructing her of her duties, Brown reminded her, “No labor leader can resist a pretty girl,” and offered her the following “side note”: “Sorry to mention this tactic, and [I am] fully aware that liberation begins [at] home, but let’s face it[,] when women want to be completely equal they lose their most powerful advantage over men.”36 European and American journalists also took note of her attire, especially the miniskirt, which Elinson described: “It was a chartreuse mini-skirt dress with a big white pointed collar … and big white buttons.”37 She often wore long white stockings and flat loafers, and accessorized with a red and black UFW badge and a UFW scarf with the union eagle on it. During the winter months, she donned an orange coat.

FIGURE 9. Elaine Elinson distributes flyers on the London docks, ca. 1969. Private collection.

Elinson’s dress sharply contrasted with the work clothes of dockworkers and the black and gray tweeds of union officials. Brown believed she cultivated this look to her “advantage,” although, as Elinson remembered, she had little choice in the matter: “I literally had no money to buy a suit, or something to look sort of presentable.” Moreover, what appeared alluring to Brown did not seem excessively so to the average Briton, who had grown accustomed to such short dresses in shops along Portobello Road, the fashion district of London.38

Fashion decisions aside, the problem of sexism confronted every woman activist who dared to become a leader in the United States or Europe. In a period when women’s liberation occupied a place alongside the antiwar movement and civil rights movements, women such as Jessica Govea and Elaine Elinson had to manage men’s perceptions of them as merely sexual objects. Govea, for example, wrote of her discomfort during a trip to Shreveport, Louisiana, where she encountered the twin challenges of racism and sexism. “Personally, it was a very bad experience as racism still has the upper hand in that area,” she wrote Chavez, “and if you think that things are bad for black men in that area they are even worse for black women and, in the South, I am a black woman.” She reported receiving “all kinds of invasions and propositions” from men in the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers until she rose to speak on behalf of the grape boycott. “I was really scared,” she admitted, “but I played it ‘cara palo cool’” (cool faced) and in the end decided that her trip was “a good experience, I suppose.”39 Similarly, Elinson remembered Britain as “a very sexist society” and the problem of discriminatory behavior toward women “rife in the trade union movement.”

Elinson did not struggle with the problem of racism; however, as Brown’s comments signaled, her age and gender presented both challenges and opportunities. What Brown labeled her “powerful advantage” made her a novelty for readers of union newspapers but also placed her in a potentially precarious position with trade union members. “These guys, in fact, were in some of the roughest trades,” Elinson recalled. “They were people who had grown up with very set ideas about the woman’s roles.” Yet, in spite of their backgrounds, trade unionists in England treated Elinson “very respectfully” and helped her whenever she asked for assistance. She theorized that her outsider status as an American made her nonthreatening to the union bosses and ingratiated her to the rank and file in the United Kingdom.

As Elinson established herself in England, British and American union officials introduced her to male union leaders who showed less respect toward women. In Sweden, for example, she attended conferences and communicated with unionists who paid more attention to her hemline than her message. She recalled, “There were a lot of guys who thought, ‘Okay, let’s just let her give her talk, and then take her home’ I didn’t feel that comfortable sometimes going to weekend conferences.”40 When Elinson requested Brown’s recommendation on how to handle such advances, he sought the help of Chavez and offered his own remedy. Chavez had “no words on the subject,” whereas Brown replied with practical, if not sympathetic advice: “I think it requires a combination of good humor and firm will—we don’t expect total sacrifice for the cause.”41

Elinson drew on her family experience and the example of other women in the movement to overcome such awkward moments. The sister of three brothers, she felt comfortable dealing with men and believed herself their equal. Her parents had instilled this confidence and rejected the idea prevalent among some of their generation that women went to college primarily to find a man to marry. “There were a lot of my contemporaries like the bright women who went to Smith,” Elinson remembered, “who really were taught by their parents or their cultural milieu [to] study art history, and then you’re going to marry a nice guy who’s going to be a doctor, or something, from Harvard.” Her parents, on the other hand, raised her to be self-sufficient and empowered her to think that she could achieve the same level of independence as her brothers. The example of Dolores Huerta weighed heavily on her mind as she began to work with leaders who viewed her presence with a jaundiced eye. Huerta, who negotiated the first labor contracts with Schenley, gave Elinson a powerful role model to emulate: “I was drawn like a magnet to Dolores.… She was one woman in the midst of all of these men. And she was way gorgeous … but she just forged ahead with all of her political passions and commitment and smarts, and you know, the fact that she may have been totally attractive to half of the people around her was not what got her going, you know?”42

Jerry Brown also treated Elinson as an equal—comments about her looks notwithstanding—and dispensed advice, support, and contact information without equivocation. Their frequent correspondence provides an impressive record of the evolution of the European boycott and evidence of Elinson’s intuition and independence.

Brown’s early advice to Elinson demonstrated a faith in the consumer boycott that was based on the union’s success in North America. Because England was the fifth largest importer of grapes and a market where growers could move unused shipments, Brown felt an urgency to educate the British public through “a one-shot provo[cative] publicity stunt against importing US grapes on the theme of helping the poor in America (which ought to appeal to British students).” In addition to students, Brown advised Elinson to target union members and government workers, who “might move to either stop grape imports (unlikely) or make a public display of displeas[ure] (likely).”43 Among his many suggestions for action, Brown amusingly advised Elinson to unfurl a “don’t buy grapes banner” from Big Ben or convince the Beatles to write a protest song, going so far as to suggest the title “Sour Grapes” before concluding, “This I leave entirely up to local imagination.”44

Elinson had to overcome a lack of resources to educate herself and the union on which strategy should be used in England. She felt the union’s notorious lack of funds and meager weekly stipend of $5 per volunteer more acutely than most leaders, given the exchange rate and the cost of communication. Although Chavez permitted a modest increase in her stipend and allowed Brown to send a bit more money as needed, the UFW relied on her to raise money, secure donations, and budget wisely—including using much of her own money set aside for education—to fund her activities. Elinson lived in less than ideal conditions, sharing a flat on the third floor of an old row house with three other graduate students. She remembered, “The place was rundown and damp; when it rained, the kitchen floor was crowded with buckets and bowls to catch the leaks, and the whole flat was heated by a rickety gas stove that had to be constantly fed shillings.” When she needed to use the phone, she had to rely on a pay phone shared among all the residents of the house in the hallway of the bottom floor.45 At the height of the British campaign, one phone bill between Brown and Elinson reached $40, prompting Brown to caution, “Don’t worry about it; but let’s try to avoid that kind of thing.”46

Cut off from immediate contact with Delano, Elinson relied primarily on her own instincts to build a campaign in London and beyond. In talking to her peers at school, she found a sympathetic group of English students and community activists steeped in the politics of anticolonialism in the former European colonies of Zimbabwe (Rhodesia), Namibia, Mozambique, and Angola. In addition, British peace activists demonstrated against the U.S. war in Vietnam and endorsed boycotts against products that supported apartheid in South Africa. All of these friends served as allies at a time of great upheaval, providing her encouragement and occasional resources in an otherwise foreign land. Yet in spite of these efforts, Elinson recognized the limitations of building an effective consumer boycott.47 Although her fellow students and friends in the peace movement and expatriate communities understood the stakes in the farm workers’ struggle, the average English consumer had a rather steep learning curve when it came to U.S. domestic politics, making it virtually impossible to generate the kind of mass support for a boycott that had been achieved in North America. Moreover, the absence of a British bill of rights with an amendment protecting free speech for individuals made Elinson and other potential volunteers vulnerable to prosecution (and in her case deportation) for telling customers not to buy grapes.48

Elinson quickly figured out that social justice for farm workers could flow more easily through the collective action of unionized laborers. Unlike in North America, where labor laws restricted allied unions from helping the UFW execute a blockade of shipments, in England unions had greater freedom to assist other workers. British labor leaders and union officials were particularly scandalized by the denial of collective bargaining rights to farm workers, a right guaranteed and defended by U.S. law for most other American workers. In this regard, Britain resembled Canada, where Marshall Ganz and Jessica Govea had cultivated alliances with leaders of organized labor who expressed their objections to the exclusion of farm workers from the National Labor Relations Act. Elinson’s goals differed from those of Ganz and Govea, however, in that she appealed to British dockworkers to create a blockade against grapes reaching English shores rather than to participate in storefront picket lines.49

Elinson made it her business to become familiar with the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU), the union representing dockworkers responsible for unloading ships carrying California table grapes. Given the presence in Delano of AFL-CIO representative, Bill Kircher, Elinson assumed she could obtain introductions to TGWU members through the European office of the AFL-CIO, the official sponsor of the UFW. In Europe, however, Elinson found the AFL-CIO icy; her attempts to contact either Irving Brown, the European representative, or Jay Lovestone, the international labor director, were futile. “My feeling is that the AFL-CIO might try to keep you from working with the radical anti-certain-aspects-of-American-policy-elements,” Brown explained, “[because the] foreign AFL-CIO is lined up with all the conservative right wing forces and not with the people who are going to help us.”50

Brown recommended working with Victor Reuther, Walter Reuther’s brother, because of the UAW’s historic support of the UFW. Reuther’s frequent trips to Europe also gave the UAW credibility with both the TGWU and the more radical members of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), the umbrella British labor organization to which the TGWU belonged. “Our goal in London,” Brown wrote Elinson, “is to have the dockers or the Transport Workers (TGWU) or the entire TUC refuse to handle a major shipment of U.S. grapes bound for England.”51 Postwar increases in U.S. imports, combined with consumers’ growing rejection of South African grapes in protest against apartheid, made U.S. grapes prevalent in British markets and an appealing target for the union.52 After a couple weeks, Brown secured Chavez’s approval for Elinson to contact TGWU officials directly to circumvent the sticky labor politics that were holding up her progress.

Elinson’s own initiative in contacting members of the TGWU proved to be the most important act in establishing relations with English dockworkers. Rather than start at the top of the organization with the general secretary, Frank Cousins, she appealed to Freddy Silberman and Reagan Scott, two writers in the Communications Department of TGWU responsible for reporting labor struggles within the union and beyond. Silberman wrote most of the stories for the union newspaper, The Record, and Scott served as editor. Elinson remembered, “Freddy was the first person to invite me into that building, which to me was like the fortress that I had to get into.” Silberman was a Holocaust survivor, making his way to England with his family by way of South Africa. As a young adult, he had attended Cornell University, giving him an instant connection to Elinson. Silberman and Scott interviewed Elinson for a feature article on the UFW—the first of its kind to appear in the British press—that led to others about her and the farm worker movement in the London Times, Manchester Guardian, and Telegraph.53

Elinson simultaneously worked with fellow graduate students on labor issues, eventually making contact with Terry Barrett, a dockworker from the Isle of Dogs on the River Thames and a member of the Socialist Workers Party who organized demonstrations committed to achieving peace in Ireland and an end to the U.S. war in Vietnam. Barrett invited Elinson down to the docks to share the story of the farm workers and introduced her to fellow dockworkers at West India, Millwall, and Tilbury. A fiery speaker, he concluded every meeting with a pledge to Elinson: “The scab California grapes would be blacked [blocked] by the British unions—and we’re going to start here and now!”54

Eventually, these dock appearances led to a formal invitation from William A. Punt, the fruit and vegetable markets section officer of the TGWU, to address a gathering of dockworkers at the main union hall in Covent Garden Market in the center of London. At a meeting of the general membership, Elinson stood before hundreds of dockworkers on “lunch” break at 7 A.M. as they cradled steaming hot cups of tea on a cold fall morning. Elinson’s stories of child labor, poverty, and high rates of tuberculosis among farm workers evoked comparisons to The Grapes of Wrath familiar to some of the members. That the National Labor Relations Board in the United States did not recognize farm workers especially shocked the membership, who saw government recognition and the right to collective bargaining as fundamental to their own health and well-being. In response, Punt secured a unanimous vote from the floor to send a resolution to the TGWU and the TUC headquarters endorsing the strike and boycott, and a letter to the U.S. Embassy announcing their intention of cooperating with the UFW. The dockworkers also made a collection of funds to support Elinson and offered to take her out for a pint when the meeting concluded, but she graciously declined.55 Elinson carried this momentum well beyond the London docks to other ports in England, including those run by longshoremen represented by the global union federation, the International Transport Workers Federation (ITWF). In every case, dockworkers expressed a deep sense of solidarity with the farm workers and their intention to help Elinson enforce a blockade of California grapes throughout England.

Media coverage of Elinson’s organizing and the TGWU’s actions finally grabbed the attention of both AFL-CIO leaders and the U.S. government. Her growing influence over British transporters compelled U.S. Labor Attaché Thomas Byrne to contact AFL-CIO president, George Meany, to find out more about the twenty-one-year-old organizer working out of a dreary cold-water flat in North London. Given the European office’s neglect of Elinson, however, Jay Lovestone could not attest to her character, forcing Meany to contact Bill Kircher in Delano. “The day your letter regarding the ITWF [support] arrived,” Brown wrote to Elinson, “Bill Kircher received a call from George Meany asking who the hell you are.” Brown’s report to Kircher that Elinson was “a ‘solid citizen’ (read: not new-left)” allayed some of Kircher’s fears and permitted him to communicate Elinson’s good intentions to Meany.

Thomas Byrne conducted his own investigation, eventually inviting Elinson to the U.S. Embassy for a chat. Although a neutral party to the conflict, the embassy had tipped its political hand by working with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to distribute bulletins advertising California grape sales in Britain. TGWU porters responsible for work onboard ships responded to Elinson’s appeal for cooperation by refusing to appear in publicity photos tied to the USDA campaign. Although the porters showed greater caution than the dockworkers in their endorsement of the boycott, their unwillingness to appear in the advertisement caused Byrne and USDA officials to worry about the extent of Elinson’s organizing.56 At their meeting, Byrne revealed the contents of a letter from Punt on behalf of Covent Garden transporters regarding Elinson’s involvement in British affairs. Punt’s statement of “hope that the members of our organization are not obliged to use their industrial strength to assist their American brothers and sisters” alarmed Byrne; he held Elinson accountable for this thinly veiled threat of labor action not sanctioned by Punt’s superiors.57 Although the meeting with Byrne indicated a level of surveillance by the U.S. government that made Elinson uncomfortable, the meeting also demonstrated progress in her efforts and gave her confidence that the “blacking” of all grapes from England was an achievable goal.58

Byrne’s message of doubt regarding the TGWU’s official position on the boycott signaled to Elinson and Brown the importance of securing a formal resolution from the union’s governing council. Although porters and dockers demonstrated an inclination to cooperate, a contact within the union, identified only as “Willis,” informed Elinson that the TGWU, by law, could not call for a blockade directly. Rather, he advised Elinson to push for the TGWU general council to “pass a resolution strongly endorsing the [UFW] strike and making the membership aware of it.” This approach worked. By early December, Elinson’s work with union officials, backed by formal appeals from Chavez and Reuther, produced an agreement by President Frank Cousins of the TGWU to bring the issue before the full body. “The job you are doing,” Brown told Elinson, “really needs a 20-year diplomat, only you’re doing better than that.”59 On December 22, 1968, Cousins released the official position of the TGWU: “The Transport and General Workers Union is advising its 1 1⁄2 million members to operate a consumer boycott of California grapes, and has written to the TUC suggesting that affiliated unions be encouraged to do likewise.” According to Jack Jones, the executive secretary of the union, the TGWU chose to support the UFW because “they were not included within the legal protection that requires American employers to recognize a representative union, and we certainly want to do what we can to help them.”60

News of the resolution thrilled the UFW back home and inspired collaboration with members of the International Longshoremen Workers Union (ILWU) in the United States. Although ILWU president, Harry Bridges, refused to endorse the strike and the boycott, many rank-and-file longshoremen showed their allegiance to the farm workers by deducting money from their monthly paychecks to support the UFW and conducting food and clothing drives for unemployed workers walking the picket lines. Two ILWU clerks, Lou Perlin in Los Angeles and Don Watson in the Bay Area, went a step further by sharing information from manifests of ships that were leaving the West Coast. “We are now working closely with the ships clerks,” Brown wrote Elinson, “who are systematically checking at both San Francisco and Los Angeles [for the location of grapes].”61 Brown also clarified the objectives for Elinson: “Our friends in the shipping industry here inform us that if we can stop one shipment (and cause all the legal, international, political problems that would involve), these shipping lines would simply refuse to take grapes to any European ports—it’s as simple as that.”62

In Britain, the resolution did not make the blockade a fait accompli, but it gave Elinson a powerful tool for organizing one. Resolutions and public speeches notwithstanding, the execution of the blockade depended on reliable dockside leadership and accurate information regarding the whereabouts of grapes located in ladings on the ship. Once again, Elinson turned to her rank-and-file allies along the docks to make the blockade a reality. At Covent Garden, she met Brian Nicholson, the head of the London docks and a member of the executive board of the TGWU. A veteran of the docks, Nicholson used his authority and imposing physical presence to bring the hustle and bustle to a screeching halt for Elinson to do her work. Elinson described the typical scene:

With the bill of lading in hand, I went down to the London docks with Brian. We would approach the team of dockworkers working on that particular ship and that particular hold. The workers would put down their ominous looking dockers’ hooks (a pointed piece of iron attached to a strong wooden grip, used to pull cargo off ships before containerization), and gather round this odd pair. Brian, a third-generation dockworker, 6’3”, in a thick sheepskin coat and cloth cap, orange sideburns, and a booming Cockney voice, would introduce me. I came up to his shoulder, had a ponytail and big mod glasses. They could hardly understand my American accent. We both wore red-and-black UFW buttons on our jackets.63

Holding the bill of lading Brown had acquired from Watson and Perlin in Oakland, Elinson scoured the contents of ships with the “walking boss” of the dock to determine the exact location of the grapes. Such transatlantic solidarity between ILWU and TGWU members transcended the political posturing of union leaders and completed a network that effectively blacked 95 percent of the grapes from reaching British shores.64

In response, growers reacted as they had before: moving the grapes to another market, this time to Scandinavia. The union had anticipated this move, given Brown’s extensive research on the quantity and location of exports, which showed that a majority of the 15 million pounds of U.S. grapes going to Europe went to the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland in 1966.65 The line of communication with West Coast clerks helped update the destination and location of grapes not only for ships going to Liverpool and London, but also those headed directly to Scandinavia. In January, Brown learned that three ships—the Brasilia, Aconcagua Valley, and San Joaquin Valley—were now bound for Stockholm, Goteborg, and Malmo in Sweden, and another, the Bolinas, was en route to Norway.

Brown promptly dispatched Elinson to Sweden. She recounted the harrowing trip across the North Sea and her arrival in Stockholm during the dead of winter: “I threw my warmest socks and sweaters in a bag, bundled up a big batch of UFW literature, and bought a pocket Swedish dictionary and a second-class ticket to Stockholm. The trip by bus, train and ferry took 48 hours. It was January, and a heavy snow blanketed the Swedish landscape. I was invited to stay in the home of an American war resister and his Swedish girlfriend who taught labor history at the university. I slept on the couch in their living room, and a floor-to-ceiling ceramic furnace kept us warm when the daily temperatures outside fell way below zero.”66 Elinson’s host, Victor Pestoff, who had fled the United States to avoid the draft, now worked part time with the International Federation of Plantation, Agricultural, and Allied Workers (IFPAAW), a global agricultural workers’ union in which the UFW maintained membership. With Pestoff’s help, Brown managed to have his allies in the ILWU telex the ships’ manifests indicating the location of the grapes to the IFPAAW office in the Netherlands, which then forwarded the information to Sweden.67

The union prepared for Elinson’s arrival by calling in favors from new and old labor friends at home and abroad. Chavez sent a letter to Victor Reuther, requesting his help in securing a proper welcome for Elinson from Swedish labor officials. “One of the problems we face in Europe,” Chavez explained to Reuther, “is being recognized as a legitimate union that is supported by the major unions like the UAW and the AFL-CIO in the United States.” Chavez’s message, of course, alluded to the ongoing trouble with the AFL-CIO European office and its failure to recognize Elinson as a representative for the union. The UAW’s departure from the AFL-CIO over political differences between Walter Reuther and George Meany in 1968 had given Reuther an opportunity to accentuate the union’s leftist credentials among European unions that tended toward socialism, especially in Sweden. Although Jay Lovestone courted more conservative leaders in Europe on behalf of the AFL-CIO, not everyone within the union agreed with him, especially Bill Kircher, who increasingly influenced Meany’s thinking about the farm workers as the popularity of the boycott swelled on both sides of the Atlantic. For the UFW, UAW assistance in Europe could prompt a more committed response from the AFL-CIO, which had to worry about its public image and protecting its turf. At worst, the AFL-CIO would continue to neglect Elinson and offer only lackluster support for the boycott abroad.

Chavez’s gamble worked. Victor Reuther responded by sending cables to his allies in the International Transport Workers Union in Sweden to request their cooperation in an extension of the blockade.68 Reuther also directed Virger Viklund, a representative for the Swedish Metalworkers Union attending a UAW meeting in Los Angeles, to visit Delano during his trip. Brown reported to Elinson, “Viklund was very interested in the strike and boycott and told me how Sweden had made a 100% effective boycott of South African grapes [to put pressure on the apartheid government].” Before leaving California, Viklund communicated his interest in supporting the UFW to Lars C. Carlsson, vice consul to the Swedish Consulate in Los Angeles, who called the Delano office to offer his help. Carlsson honored Brown’s request to secure a formal invitation from the Swedish Trade Union Federation for Elinson and gave Brown contact information for transport workers responsible for unloading grapes throughout Scandinavia.

Elinson received a hero’s welcome in Sweden. “The Swedish unions,” she recalled, “were even more anxious to help—if that is possible—than the British ones.”69 The success of organized labor in Sweden to secure health care, pensions, educational funds, and job security produced a pro-labor public that was open to the appeals of the UFW. A burgeoning oil industry in the North Sea accounted for much of Sweden’s collective wealth, and a spirit of generosity pervaded Swedish society that was manifested in a general willingness to participate in movements for social justice. “In a country as homogenous, liberal, and tight-knit as Sweden,” Brown advised, “I don’t think that we should discount the possibility of an effective consumer boycott.”70 The leading role Swedish consumers played in the boycotts against South African products to protest apartheid and peace demonstrations in the streets of Stockholm against the war in Vietnam informed Brown’s advice. Chavez and Brown made overtures to the Swedish Food Cooperative, Kooperative Foerbundet, where 30 percent of Swedes did their shopping. They sent stories regarding the unsanitary conditions under which field workers labored to the Swedish Consumer Cooperative journal and magazine editors in hopes of spurring a boycott of California grapes.71

Yet for all the potential of a consumer boycott in Sweden, Elinson discouraged such talk, focusing primarily on work with the unions. The absence of a ready army of volunteers and the need for Elinson to manage several fronts from a foreign location made pursuing such a strategy impossible. Although Elinson spoke English, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, and French, she had little grasp of the Swedish language and depended on sympathetic journalists to communicate her message. When given the opportunity, she used newspapers to communicate directly to dockworkers. “Two boats, the Aconcagua Valley and the San Joaquin Valley, have just been forced to change course and are now en route to Sweden,” she told one reporter. Placing a finer point on her message, she added, “You must do the same thing as the English have done; otherwise things will never get straightened up back home.”72 Elinson reinforced her message by focusing her activities on convincing the Swedish transporters to support the blockade of grapes. She immediately made contact with Reuther’s friends in the Swedish Trade Unions and the Transport Workers Union, securing an official tour of the main ports and the assistance of a translator. In response, the Swedish Trade Unions hosted a press conference to announce their support for the boycott, and the transporters directed her to Malmo, Sweden, in anticipation of the arrival of the grapes.

Ever conscious of both practicality and style, Elinson boarded the train for the southern port of Malmo, dressed in a brand-new pair of reindeer-skin boots—courtesy of the Swedish farm workers’ union—heavy stockings, and a long wool skirt covered by a floor-length shawl. When she arrived, trade unionists, port officials, reporters, and TV cameras covered the docks. The lading crew had already taken the position that they would not unload cargo until Elinson could board the ship to ensure that the dockworkers did not remove boxes of grapes with the rest of the freight. The captain stood at the bow of the ship, arguing with the shop steward that all of the grapes had been unloaded in London. “Well then,” the steward responded, “we are going on the ship, and you are going to show us there are no grapes in there.” By union contract, the captain could not refuse the shop steward entry to the vessel, but he insisted that Elinson not come on board. Neither side would budge from its position.