THE REGIONAL OFFICE of the new Agricultural Labor Relations Board (ALRB) in Salinas, California, opened on a typically cool morning, September 2, 1975. The union had planned for this day for months, collecting membership cards and preparing petitions for elections on farms. The Salinas office covered farms over a wide swath of the state, from the coastal growing regions just north of Los Angeles to the fertile lands of Monterey County. Union organizer, Jesus “Chui” Villegas, and a law student interning for the farm workers had driven all night from Oxnard, nearly 300 miles away, carrying seven petitions to file with the ALRB on its first day of operations. Sandy Nathan, a young cause lawyer who had joined the UFW team in 1973, met Villegas at the farm workers’ office before dawn to go over the petitions and combine them with cards collected from local ranches and fourteen petitions prepared over the previous hours.1 Nathan embraced the new law as an opportunity to prove that the union could achieve justice through the system. Many rank-and-file members of the union shared this optimism, congregating in front of the office a day before, on Labor Day, to hold a mass at 5 o’clock in the afternoon, followed by an all-night vigil to pray for the success of the new law.

At a quarter to eight on the morning of September 2, Nathan and Villegas arrived at the board office, met by throngs of farm workers and television reporters waiting with great anticipation. The office director, Norman Greer, and members of his new staff began to move supplies in and out of the building in anticipation of the big day. Nathan, Villegas, Marshall Ganz, and the rest of the workers remained close to the front door, though each time a staff member needed to pass, the courteous but anxious crowd made way for him. “We were kind of standing off to the side of the door,” Nathan remembered, “and presumably they were going to say, at some point, that they were ready to go.” That moment never came. Instead, as Nathan and Villegas looked on, Greer and his regional attorney, Ralph Pérez, cut a path to the parking lot. Nathan recalled what he witnessed next: “What had happened, it turned out, a couple of the Salinas cops told me that José Charles [a Teamsters representative] and one of his companions from the Teamsters were out in the parking lot and they asked the cop to go inside and tell Greer they wanted to talk to him. They didn’t want to walk through the UFW line, so Greer and Pérez went out [to them]. The next thing we see, here’s Greer leading the Teamsters into the office ahead of us. So I said, ‘Let’s go!’ And all the people went in, and I went in.”2

Within minutes the scene turned chaotic, as Villegas insisted that he be the first to file a petition after traveling all night and having fellow farm workers hold his place. With television cameras rolling and Villegas, Ganz, Nathan, the Teamsters representatives, and about ten farm workers crowded into the small office, Greer began shouting, “This is a mob! There’s an unruly mob in here! I’m not going to take these petitions until you get them out of here!” Greer directed most of his ire at Nathan and Ganz, whom he assumed had staged a publicity stunt. In the heat of the argument, Greer also uttered a racially tinged concern about getting his “pocket picked,” inflaming tensions even more. Nathan opined later, “It was just incredible that after all this—I mean it was like a festive occasion—suddenly this guy was hitting his hand on the counter, saying they’re not going to take any petitions until this mob gets out of here.”3

This inauspicious beginning to the labor board tempered union members’ expectations and, in many ways, confirmed their worst fears. In the months that followed, insensitivity toward farm workers, internal rivalries between young and old government agents, and general mismanagement from the top down plagued the board and inspired challenges to the new law from those most concerned about delivering justice to farm workers in California. In the years leading up to the passage of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, Cesar Chavez had resisted a legislative solution to farm worker troubles. After receiving funds from the AFL-CIO in 1973, however, Chavez shifted his position, asking Jerry Cohen to propose the most liberal, pro-union labor relations act that would extend collective bargaining rights to farm workers without compromising the union’s most coveted strategy: the secondary boycott. The time seemed right given that the staunchly anti-union governor, Ronald Reagan, had concluded his second and last term in 1974 and California’s electorate had replaced him with the young, ex-Jesuit seminarian, Edmund G. “Jerry” Brown. As the attorney general under Reagan, Brown had watched his predecessor’s willful neglect of the farm workers, frequently entreating him to take a more active role in the resolution of the conflict. Now, as the governor of California, Brown promised “to extend the rule of law to the agriculture sector and establish the right of secret ballot elections for farm workers.”4 These were the circumstances under which the ALRA was born; however, the results on September 2, 1975, looked far different from those that Cohen had negotiated or Brown and his legislative partners had intended.

The failure of the ALRB to live up to its expectations surprised union officials who had worked diligently in the years and months since the battle of Coachella to get a “good law.”5 Chavez sent Cohen and Nathan to the state capitol during the preceding months to work closely with sympathetic lawmakers, California’s secretary of agriculture and services Rose Bird, and Governor Jerry Brown on legislation that they thought gave them the best chance to succeed. The UFW lobbying group in Sacramento succeeded in improving upon all the rights afforded to industrial workers in the NLRA for agricultural workers, including securing the right to a secondary boycott with limited restrictions. Although the law remained irritatingly vague on eligibility to vote and how to recognize workers’ interest in an election, the final version, passed on May 29, 1975, required elections to be held at the peak of the seasonal harvests. The law’s promise to “[ensure] peace in the agricultural fields by … [bringing] certainty and a sense of fair play to a presently unstable and potentially volatile condition in the state,” simultaneously acknowledged a tumultuous past and present while casting a hopeful eye toward the future.6 In describing the law to the union members after its passage, Cohen assured them of their right to boycott, but reminded everyone that the bill’s implementation still required their hard work. “We have the solution,” Cohen proudly reported, “now all we need is to work out the details.”7

The difficult first months of implementation, however, produced new doubts about the efficacy of a legislative solution and renewed suspicions that the state government was ill-equipped to manage the fight in the fields. Although journalists hailed the passage of the law as the “dawn of a new era for farm workers,” and Jerry Brown later proclaimed it “the greatest accomplishment of my administration,” those who struggled to make it work found it less effective as a tool for justice.8 Indeed, Chavez strained to defend the law after two months of frustration, while members of the UFW legal team debated whether the law was, in fact, truly good for the workers. Jerry Goldman, a veteran UAW attorney working on loan to the UFW legal team, rendered his verdict after just three weeks on the job: “I think this is one of the most anti-union laws I have ever seen.”9 Nathan believed it was “the administration of the law, not the law” itself that produced the anti-union bias.10

Chavez, Nathan, and Cohen had little choice but to be optimistic. In addition to the promise Chavez had made to George Meany to pursue such a solution, the UFW approached the formation of ALRA in its weakest state since its founding, with only twenty union contracts and 15,000 members during the peak harvest season.11 In this context, the union had few options other than to enter into a Faustian pact with Brown and the state for its survival. In embracing the challenge to work within the confines of the new law, the union set out, once again, to prove that it could adapt to the changing dynamics of the struggle and stay one step ahead of its rivals.

THEY’RE FOR THE STATE

The Agricultural Labor Relations Act, at least on paper, gave UFW organizers reason to be hopeful, although it also offered the Teamsters and the growers a chance to win in union elections. At a basic level, the ALRA recognized farm workers’ rights to organize and join labor unions. The law also set up provisions for filing unfair labor practices against growers and competing unions who interfered with this process or impinged on the free will of workers to determine their own fate. In cases where the board affirmed claims involving unfair termination of employment, the law instituted a “make-whole” remedy, whereby the employer would have to pay the worker the difference between what he received and what he would have been paid if the employer had bargained in good faith.

Although Teamsters officials opposed these new regulations during the legislative process, they softened their position over time. The ALRA allowed the Teamsters to retain their existing contracts, which totaled some 467 farm labor contracts and covered approximately 65,000 members at the time of its signing.12 The Teamsters stood to lose in the upcoming elections, but the head of the Western Conference of Teamsters, M. E. (Andy) Anderson, remained confident that they could hold on to their advantage, given the presumed superiority of their contracts. The legislation applied strictly to agricultural field workers only, thereby protecting the employees covered by the Teamsters in warehouse and hauling from UFW infringements.

For the growers, the law implemented stricter guidelines for picketing and boycotts; specifically, it forbade the “hard boycott” (also known as a “traditional boycott”), in which unions asked employees not to handle a particular product, and restricted the right to boycott to labor organizations currently certified as the representatives of the primary employer’s employees.13 The law restricted use of the secondary boycott if the union lost an election, though loopholes remained for the UFW to continue its campaigns against grapes, lettuce, and Gallo wine. The grower newspaper, the Packer, initially declare an end to the boycott; however, within a week it published a retraction.14 The growers successfully petitioned for restrictions on the use of recognitional strikes, which would have allowed employees to select a union as their bargaining representative by having a majority of the unit walk off the job.15 Instead, the law provided for the expeditious creation of secret ballot elections to determine representation—or no representation—by a union for those ranches where 50 percent of the employees exhibited a “showing of interest.” In short, the law gave something to everyone, although most regarded the ALRA as more favorable to unions than the federal NLRA.16

A week after Brown signed the ALRA into law on June 5, 1975, Cesar Chavez announced to a group of union field officers, staff, and the full executive board, “The decisions we make today—or fail to make today—will have a profound effect on the future of the union.”17 Members discussed what approach they would take to secure elections on ranches across the state and tackled the thorny issue of whether to organize undocumented workers, whom Chavez referred to as “illegals” in the common parlance of the day. Cesar’s cousin Manuel upheld the importance of illegal aliens as “economic strikers” whose eligibility should not be challenged and expressed the sincere belief “that illegals can be organized just like all other workers.” Jerry Cohen, who tried to remain agnostic on the question, admitted that the new law did not deal with the issue, but he offered his legal opinion that “it would be unconstitutional to prohibit illegals [from voting].”18 Seeing an opportunity to strengthen his point, Manuel Chavez observed, “Illegals [were] no longer afraid of the migra [federal immigration officials]” largely because enforcement had grown lax and most members of the union had undocumented relatives in their families. Ben Maddock, a Delano organizer working in the Central Valley town of Lost Hills, shared that although most of the members with whom he had spoken did not want undocumented workers to vote, he agreed that “some of the members have illegals at home, so there’s a contradiction.” The Fresno area organizer agreed with Manuel Chavez, adding, “[We] will lose without them.” In response, Manuel offered to travel to the Fresno area to have undocumented workers sign cards and to push for residency for those who chose to work with the union and labor in the fields. Displaying Machiavellian reasoning, however, he also suggested that such actions could be used to the benefit of the union: “[We won’t] ask whether the worker [is] illegal or not, but if [we] lose [the] election, then [we will] blow [the] whistle on him!”19

Cesar Chavez and Gilbert Padilla took the opposite position. Chavez offered a response consistent with the standard industrial union line: “Meat cutters, UAW and Steel Workers all have lost elections because of the illegals.” Padilla, who had worked closely with members of established unions in building the boycott, shared the position that “unions are weakened if illegals are allowed to be members.” Most union leaders believed that the lack of citizenship made undocumented workers vulnerable to expulsion and therefore much more pliable and less inclined to speak out against injustice when it happened. The use of undocumented workers as scab laborers to replace striking workers during the early days of the union suggested to Chavez and Padilla that undocumented workers could never become equal members and would ultimately only hurt the union if included. Both rejected the idea that the ALRA and the filial loyalties among union members gave the union cover to organize among the undocumented. Chavez cited the upswing in growers’ hiring of undocumented workers as evidence that they would “use [the] same work force to break elections as they did to break strikes.” “We don’t want chattels as members,” he announced at the meeting. “Even if we win elections with them, we don’t win.” In his most extreme interpretation of the problem, Chavez saw the flood of undocumented laborers into the fields as a “CIA operation” designed to serve multiple political objectives, including the restoration of the bracero program and an attempt to alleviate Mexico of radical farm workers who, if allowed to stay in the United States, would foment a communist revolution south of the border.20

Chavez’s desire to exclude undocumented workers from the union sharply contrasted with the union’s advocacy for a state labor relations act that accounted for the unique conditions of agricultural workers. That the new law accounted for their vulnerabilities—for example, insisting on elections during the peak of harvests—opened the door for the UFW to make enormous gains among this mostly Spanish-speaking group of laborers. Chavez, however, rejected the advice of some of his field organizers, including his cousin’s, in favor of a traditional union philosophy that held the line between documented and undocumented workers. He suggested that the state should address the problem by stopping the “coyote” from transporting the workers in the first place rather than focusing on the labor contractor who hired the workers at the work site. Cohen found this position disingenuous given that the law now held growers accountable for the contractor’s actions. But this too had become another unenforced provision within the law that would grow in significance as growers tried to increase their distance from the hiring process throughout the late 1970s. On this day, however, the members could not reach an agreement on an approach and ultimately agreed to return to it after two weeks of study.21 When Manuel returned from Fresno with news of progress in organizing undocumented workers to vote for the union, Cesar remained doubtful, claiming, “Illegals, not Teamsters, are our biggest problem.”22

The union upheld the relevance of the boycott, but the majority of the union’s efforts would now go toward confirming the desire of documented workers to have ALRB-sanctioned elections. The union’s lawyers also took on a new watchdog role, filing unfair labor practice charges against growers who sought to curb the influence of the United Farm Workers by firing employees who demonstrated an inclination to vote for the union. The union remained committed to a range of activities, including managing the boycott and a number of social services, although during the summer of 1975 the UFW redirected most of its resources toward making the most of the ALRB.

The unfortunate incidents in Salinas, however, represented just the beginning of problems within the board that kept it from becoming a full partner for justice. In the weeks that followed the opening of the ALRB office, lawyers working for the union complained that former NLRB operatives dominated the staff of the new agencies and failed to implement the law. According to Sandy Nathan, “They [brought] all the NLRB notions with them and under the NLRB, after you file for an election it takes a number of months before it actually happens.”23 The ALRA stipulated that elections must be held within seven days of a valid showing of interest, and the UFW insisted on such a provision because of the itinerant status of field laborers. But coming mostly from industrial sites, many of the ALRB agents did not appreciate the need for timeliness. The agents dragged their feet on enforcing the provision to hold elections during the peak harvest, and the board ultimately failed to offer an acceptable remedy when UFW lawyers complained.24

Board agents tended to be too trusting of the employers, accepting at face value the list of employees submitted to the office. According to Nathan, employers often “inflated the number of people,” which had a detrimental effect on the union’s ability to prove that at least 50 percent of the employees wanted an election. Nathan explained, “If we claim there’s 200 and the growers claim there’s 300, [and] if we have 140 cards thinking we’re well over what we need, we in fact are short.”25 When the lawyers challenged the list, agents refused to examine the grower’s payroll, arguing that they either had “no time” or “no reason” to doubt the grower’s claims. In one case, where the union compelled a sympathetic agent to evaluate the payroll in Calexico, the grower submitted an address on Airport Boulevard for 300 men, women, and children who worked on the ranch. When the union conducted its own investigation at the site, they found a single men’s camp housing approximately forty men, but the board office in the region refused to verify their findings. “It’s common,” Nathan shared, “that the lists contain twenty-five per cent inflations in most of the big places.”26 In some cases, UFW lawyers found evidence not only of blind trust in the employers, but of actual communications between board agents and growers in which the two worked out the final version of the list.27 According to Nathan, “The first week we spent fighting because they kept trying to throw us out of elections.… I was in that office day and night, just screaming all the time.”28

When the board finally held elections, they often failed to provide a transparent process that assuaged workers’ fears of employer and Teamster retribution for supporting the UFW. Since elections were new to most workers, the board held preelection conferences with employees to explain the process. Such conferences, however, occurred at the whim of the employer, usually after hours at the ranch, making it inconvenient for most workers to attend. Although UFW lawyers insisted that board members conduct the conferences in both Spanish and English and translate all documents into Tagalog, Spanish, and English, the agency refused. Nathan recalled, “[The agents would] say, ‘why don’t [you] translate the important stuff into Spanish?,’” and he would respond, “ ‘We’ll conduct the thing in Spanish and translate the important stuff into English for the employer.’”29 Needless to say, the agents declined. On the day of elections, growers often provided transportation to the polls only for workers who supported their position. Growers also covered the air travel of board agents charged with the task of monitoring elections and often treated board agents to extravagant lunches and luxurious transportation while in the field.

During the counting of the ballots, myriad problems arose. Often, non-Spanish-speaking agents threw out ballots of voters whose last names they could not read. In other instances, agents assumed Spanish surnames that appeared to be similar were repeat voters and invalidated those ballots without consulting with the union.30 Growers and Teamsters also engaged in downright intimidation of workers who they knew preferred the UFW. Nathan recalled, “People are getting fired, threatened, pushed around in all kinds of ways, and if they’d only gone out after one grower, maybe taught somebody a lesson, maybe there would have been a fair atmosphere in those elections.” During the first three weeks of the law, the UFW filed twenty-two unfair labor practices; the board neglected to act on a single one.31

Confidential reports from within the Salinas ALRB office confirmed the biases that the union lawyers perceived from the outside. During the first few weeks of the agency’s operation, a young Salinas agent, Ellen Greenstone, disclosed her frustrations with the management of the office. “Probably the most characteristic thing about our office,” she explained to Chavez biographer Jacques E. Levy, “is how racist it is.” Greenstone worked with thirty-nine colleagues in Salinas and nine field agents in Ventura. “A lot of agents won’t even listen to UFW people,” she reported. “They discount them totally.” Greenstone attributed such treatment to a lack of familiarity with workers and a prevailing attitude of noblesse oblige among her colleagues. According to Greenstone, many of the agents assumed a significant level of ignorance among the farm workers and rejected the importance of talking to them. When Greer’s actions on the first day elicited strong reactions from the farm workers, many agents were “taken aback” and “shocked” at the stridency of the UFW representatives. “Part of it was [the agents] thought they were being involved in a paternalistic, benevolent helping of workers,” Greenstone opined, “and they didn’t realize that all of these people were in a total uproar and had been battling it out for years.” When farm workers and UFW representatives challenged the agents, most of Greenstone’s colleagues became incredulous, asking, “How can these people act this way?” and “Why don’t they take our help?” “In reality,” she added, “the board agents didn’t know anything about what was going on.”32

To convey the level of danger, UFW representatives invited witnesses to accompany them into the fields. Esther Padilla, a longtime member of the UFW and the wife of the union’s cofounder Gilbert Padilla, likened the conditions in rural California to Selma, Alabama, in 1965, during the height of the civil rights movement. She remembered, “[The growers] had the dogs, and the bats, and everything else waiting to beat the hell out of us … and intimidating the workers.” Although the ALRA included a provision for union access to farms during elections, this was honored more in the breach than in the observance. The union tested the law by sending representatives to the farms during lunch hour and after work. During one of these trips, Esther Padilla and three other members entered the Metzler farm in the small town of Del Rey, just outside of Fresno. Anticipating violence, the UFW team invited the local television station, Channel 30, to accompany them. “The growers were absolutely livid,” Padilla recalled, but the presence of the media forced them to temper their response. When the same group went back at the end of the day, this time without the television cameras, a grower pulled a rifle on Padilla. At the nearby Guerrero farm, another team of union officials encountered similar hostility from gun-toting growers.33 Elsewhere in San Joaquin and Tulare counties, ranchers formed a citizens “posse” that threatened to plunge rural communities back into the violence of the previous two years.34 When the union reported these incidents to the ALRB office, agents tended not to believe them.

Much of the agents’ ignorance stemmed from their poor training on farm labor issues. The Sacramento office, run by Walter Kintz, hired retired members of the NLRB to staff the training sessions in the state capital before dispersing the agents to the field offices. The NLRB veterans imparted useful knowledge about how to run a union election, but demonstrated a profound lack of appreciation for the likelihood of violence in the fields. Greenstone found that retired NLRB members “couldn’t at all anticipate reality” and failed to prepare ALRB agents for the intensity of the conflict. When the Sacramento office arranged a field trip for the would-be agents to get acquainted with the work, members of the grower-oriented Farm Bureau escorted the group aboard National Guard buses. The Bureau used the visit as a public relations opportunity, allowing agents to speak only to labor contractors and giving what Greenstone regarded as a “false picture of what it was like in the field.” When the agents relocated to their field office, the local office manager maintained distance from the farm workers. According to Greenstone, Greer and her colleagues “never saw workers until they showed up to file petitions in our office.”35

Kintz’s decision to hire mostly veteran state bureaucrats as agents rankled UFW representatives and produced tension with some of the younger ALRB staff members, many of whom had come straight out of law school. Several older agents had served in state civil service agencies prior to joining the ALRB and assumed a balance of power in agriculture between workers and employers that existed in industrial settings. The media coverage of the strikes and boycotts in the years leading to the passage of the ALRA created an illusion of power for the UFW. Jerry Goldman, for example, complained about a “lack of sensitivity … and not knowing anything about agriculture” among agents, and “the presumption that UFW is a radical, trouble-making organization and the employers are good and honest and the Teamsters are good and honest.”36 According to Greenstone, the unfamiliarity with “the sophistication of all of this struggle and the fight that has been going on” led many of her senior colleagues to underestimate the potential for chicanery on the part of growers and Teamsters and anger on the part of the UFW. “The attitude, ‘well, I’m the board agent and I decide’ is really disturbing,” Greenstone told Levy, “because they don’t have any feeling for what goes on out there.”37

Greenstone attributed much of the insensitivity to “older people” within the office, revealing a generational and gender divide among government agents. Whereas many of the older agents joined the office as permanent members of the team, given their years of experience, younger agents like Greenstone received “temporary” jobs and inferior assignments. In the Salinas office, for example, Greer broke the agents into teams of three to conduct elections and selected team leaders based on seniority. As a consequence, older members stymied the opinions of younger agents who spoke Spanish and possessed a fresh interpretation of the conflict untainted by biases developed over years of bureaucratic work in state agencies dealing with mostly white, English-speaking industrial laborers. In some local offices, younger members included former farm workers whose experience and concerns older colleagues discredited. Greenstone recalled one incident in which a former farm worker was branded as pro-UFW simply for arguing that agents should take migration patterns into account when scheduling elections.38 Greenstone also found most of the leaders resistant to translating documents and holding bilingual meetings. When younger agents complained, the heads of teams assigned them to secretarial duties. The disproportionate number of men to women in senior leadership positions added a gender dimension to this tension. Greenstone, a younger bilingual agent, felt “a lot of sexism” within the board office and believed her “downgraded” assignments to be a consequence of “more men than women in [the] office.”39

After weeks of UFW complaints and internal discord, Kintz finally replaced Norman Greer with Paula Paily in the Salinas office, but only on a temporary basis. Greenstone had a much higher regard for Paily’s leadership, especially because Paily paid greater attention to complaints from women and younger agents. Paily put an immediate end to agents accepting chartered flights from growers and stopped employers from bussing in workers to participate in union elections. Her reasons for ending these practices, however, had more to do with restoring a “sense of fair play” and less to do with acknowledging a culture of disregard for farm workers among her own staff. She told the Salinas agents, “These elections are not for the growers, they’re not for the UFW, they’re not for the Teamsters; they’re for the state.”40

This new approach stopped the most egregious manipulations of the new law, but Paily and the majority of her staff remained ignorant of the intensity of the battle and did nothing to address attitudes favorable to the growers and the Teamsters. Her reasoning also conflicted with the sentiments among a majority of governor-appointed board members in Sacramento, who saw the law as an opportunity to bring social justice to the fields. Governor Brown appointed LeRoy Chatfield to the ALRB and tapped Catholic bishop Roger Mahoney to be chair. Another pro-labor appointee, Jerome Waldie, articulated the sentiment among the board’s majority: “I make no bones about my belief that the law was enacted to protect farm workers in their effort to organize for collective bargaining.”41 Yet the prevailing attitude among agents in the field undermined this interpretation.42 For Greenstone, who came of age during the boycott and had joined the ALRB with the intent of becoming an agent of justice rather than a career bureaucrat, such interpretations did not sit well. Within the year she left the board, deciding to work for the UFW before moving to private practice.43

The failures contributed to a growing skepticism among UFW lawyers that the law would become a solution to farm worker problems. Jerry Goldman became utterly exasperated with the process: “I am so totally frustrated. Because these acts can work, and all my life I’ve been saying that, in the private sector. If you engage in obfuscation, if you are not empathetic, if you are not understanding, if you do not communicate, if you do not treat everybody on a fair basis, these fucking acts aren’t going to work, and if that is what they want, for it not to work, they’re sure as hell doing a damn good fucking job of doing it. And I want to tell you my feeling is that they don’t want it to work.”44 Most union lawyers shared Goldman’s frustration, if not his pessimism. Nathan and Cohen, however, insisted that if the union could enforce sections of the law that required elections within seven days of a showing of interest by workers, they could turn the tide in their favor.45

UFW lawyers also demanded better access to workers. During the ALRA’s creation growers had vehemently but unsuccessfully resisted a provision to allow unions to campaign on their property one hour before work began and one hour at the end of the day. Once the legislation became law, growers tested the ALRB by impeding the UFW. For example, when UFW representatives attempted to enter fields and labor camps, grower-paid security guards chased them off the property, forcing board agents to weigh in on the matter. The UFW filed numerous unfair labor practices to address the situation, yet often the regional directors claimed to have their hands full with staging elections. In some regional offices, directors did not regard providing equal access a part of their job description. According to Greenstone, Greer told the agents in Salinas “it was not [their] business to enforce” the access rule, inviting growers to violate the law at will.46

In the courts, the South Central Farmers Committee successfully obtained an injunction against the UFW, blocking labor union representatives from entering the fields without grower permission.47 Cohen and the UFW lawyers appealed to a higher court to suspend the ruling, but the problem of enforcement of the access rule continued to plague the UFW. According to one report, the UFW could have won 15 to 20 percent more votes in elections if the ALRB had enforced the law and policed distortions in lists of eligible voters.48

During the elections, the UFW kept growers honest and consumers informed by maintaining a strong boycott of Gallo wine, California grapes, and lettuce. Given the volunteer nature of the boycott, many of the activists who made the first boycott successful had moved on, although some veterans remained to show new devotees how to build a campaign. Among them, Eliseo Medina excelled as he had in Chicago. Besides organizing workers in the California fields during elections, Medina managed a staff of twenty-eight volunteers in Chicago who, at one point, drew a crowd of 1,100 people to march on Jewell Market. The Chicago boycott house garnered 20,000 signatures asking Jewell’s ownership to divest from Gallo and raised $26,000 at a screening of the film Fight for Our Lives, documenting the 1973 battle for Coachella. Some of the money went toward a campaign started by members of the community to elect Medina chairman of Jewell’s board of trustees. In his reports to La Paz, Medina wrote that support in Chicago was “far stronger than before.”49

Elsewhere old hands such as Gilbert Padilla, Jessica Govea, and Pete Velasco contributed their experience. Like Medina, they balanced service on the National Executive Board and work on elections in California with orchestrating boycott houses far from La Paz. Gilbert and Esther Padilla managed a staff of fourteen volunteers in Washington, D.C. and Virginia. Pete Velasco, one of two Filipinos on the executive board, traveled to Baltimore to lead the boycott and succeeded in securing support from the city’s mayor and Maryland’s governor. Govea returned to Canada, now charged with managing a staff of forty-one volunteers spread throughout Ottawa, Toronto, Montreal, and other cities. Although the infrastructure she and Ganz had put in place during the run-up to the 1970 contracts allowed her to plug back in and manage the houses from Toronto, her value as a credible voice among farm workers during elections required her to divide her time between California and Canada.

Chavez and members of the executive board recognized that these assignments removed effective labor organizers from the elections at a critical moment, yet attachment to the boycott made backing away from the campaign unacceptable. Chavez held firm to the belief that contracts could be attained only in tandem with an effective boycott, and he continued to channel funds toward a reduced staff of volunteers in 150 cities across the country, including five in Denver, thirteen in Detroit, three in Minneapolis, seven in Pittsburgh, fourteen in St. Louis, fifteen in Philadelphia, four in Seattle, three in Houston, two in Portland, Oregon, and two in Atlanta. These numbers were far smaller than the boycott in its heyday; however, the existence of a boycott house kept growers on their toes.

The network also included more boycott houses abroad. Victor Pestoff, who had assisted Elinson during the 1969–70 season, became the European director of the boycott and moved between Norway and Switzerland securing the support of Scandinavian labor organizations and cooperative markets. The Council of Nordic Trade Unions gave $7,500 to the cause, and two Danish and one Swedish co-op voted not to carry California grapes on their shelves. Elinson, who had gone back to graduate school in the United States after 1970, once again found academic work tedious and contacted Chavez’s brother, Richard, to see if she could assist. Her timing turned out to be perfect since the Teamsters had begun to counter the UFW campaign in 1975 by putting pressure on their fellow transporters in England not to cooperate. As members of the International Transport Workers Federation, the Teamsters and the Transport and General Workers Union belonged to a common international union, which made support of the UFW much more difficult.

Richard Chavez sent Elinson to England in hopes that her connections with the TGWU could break through Teamster opposition and again forge a strong alliance with the English dockworkers. In spite of the Teamsters’ activities, Elinson found the work much easier compared to 1969. “This time,” she recalled, “the union had much more of a name and much more of a presence.” The BBC aired documentary films about the UFW in Britain, and union journalists knew of Elinson from her previous stint, making her a familiar face in both England and Ireland. The success of the union and Elinson’s modest celebrity also earned her office space at the World Peace Council in central London, a far cry from the tenement apartment she had worked out of in 1969 and 1970. Elinson also quickly reestablished relations with Freddy Silberman and Brian Nicholson in the TGWU, the latter having advanced to president of the union between the two boycotts. Nicholson had recently divorced, and he and Elinson fell in love and married. Her familiarity with the British public, the trade unions, and old friends like Silberman and Nicholson helped her overcome the Teamsters’ resistance. Of the work, Elinson recalled, “We were doing a lot more kinds of newspaper articles, meetings, and speaking at conferences, and speaking at the Labour Party conferences and things like that rather than tromping around on the docks, looking for grapes.”50

The international component of the boycott also included Asia. In Japan, the UFW made contacts with dockworkers to support a blockade, while in Hong Kong a committee of fifteen, including GIs stationed in the area, worked on behalf of the union to boycott Gallo wine. The great distance from the center of the boycott, however, created the potential for deviations from the nonviolent strategy advocated by Chavez. In Hong Kong, for example, three organizers were found guilty on eleven counts of arson for burning down a storage facility holding grapes. The judge sentenced the three to eleven months in jail, and the image of the union overseas was temporarily tarnished.51

Closer to home, the union diversified its use of the boycott in California by threatening to use it against the state if either the general counsel or the governor did not enforce the new labor law. Although most observers saw Governor Brown and the ALRB as allies to the farm workers, union officials worked hard to bend the governor and the board their way by threatening to withdraw from the legislative solution in which both had become deeply invested. Brown, for example, had staked his political future on the success of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA) early in his first term, and ALRB directors and agents had jobs only as long as the union agreed to use it as a tool for achieving their objectives. “The situation is already bad and getting worse as the growers and Teamsters see they can get away with their coercive tactics,” Dolores Huerta told a reporter. Turning to the familiar tool of the boycott, Huerta threatened, “If those tactics are not stopped, we will have no choice but to boycott the whole election process.”52 Although the union refrained from ever calling a formal boycott of the ALRB, it picketed both regional offices and the main Sacramento office to bring attention to the agency’s deficiencies.

In response, the governor appealed to Sam Cohen, a respected attorney with a lucrative private practice in San Francisco, to head a special task force to deal with the backlog of unfair labor practice complaints and organize the field operations of the state agency. Cohen’s guidance had an immediate effect in the Imperial Valley, turning what had been seen as a regional office in crisis into “a whirlwind of efficiency.”53 The regional board director in El Centro, Maurice Jourdane, pulled back from the brink of quitting when Cohen came to the office and imposed a “sense of dedication and determination to make the law work.” As in other regional board offices, the workload overwhelmed the staff, turning the office into a “sit-back-and-wait agency” that usually reacted to violations of the law long after the workers had given up hope in the process. “When I first began working with the agency,” Jourdane told a reporter, “I was appalled by what I saw in the fields.… Workers were frightened.”

After Cohen arrived, agents took a proactive approach, fanning out into the Imperial Valley to inform employees of their rights and ensuring their ability to vote without fear of reprisal. Unlike Greer or Paily in Salinas, Jourdane, a thirty-three-year-old attorney, embraced the law as an opportunity to bring justice to the farm workers. Growers and Teamsters routinely attacked Jourdane, accusing him of being pro-UFW whenever he tried to enforce the law. Contrary to Paily’s position, Jourdane believed the “specific intent of the law … was to give workers the free, un-coerced right to choose a union, or no union, by secret ballot.” Thanks to the reforms instituted by Brown and implemented by Cohen, Jourdane now felt “that is what we are doing at last.”54

The threat of a boycott and the aggressive action by Cohen and the UFW legal team helped the union win far more elections than it lost. By the end of December 1975, the state had managed to hold a remarkable 354 elections without one strike or the defections of the union from the process. Of these 354 elections, the UFW scored victories in 189 of them, representing 26,956 workers, or 50.2 percent of voters. The Teamsters, on the other hand, won 101 elections representing 12,284 workers, or 23 percent. Among these totals, fifty-eight ranches involving 8,228 workers switched from the Teamsters to the UFW. In the contest to win elections where either the UFW or the Teamsters held contracts already, the UFW fared much better than its rival. The UFW won all of its elections where it held contracts, whereas the Teamsters lost 58 percent of the workers they had held under contract on 177 ranches prior to the elections in 1975. Finally, in spite of the growers’ vigorous campaign against unions among employees, only six ranches involving 938 workers switched from either the UFW or the Teamsters to no union at all. In fact, growers succeeded in convincing only 4 percent of the workers to vote for no representation in twenty elections.55

Union officials had their hopes tempered, however, by a number of ominous trends that continued to threaten the new law. A victory in an election won the union the exclusive right to negotiate a contract but did not ensure one. The difficult work of negotiating with their adversaries lay ahead. Growers, Teamsters, and UFW officials continued to challenge the results of more than 75 percent of the elections, which delayed certification of the results. Indeed, the UFW legal team led all parties in the submission of unfair labor practices, triggering a series of hearings to settle the matter against eighty-five growers. The level of activity far exceeded the expectations of the state, forcing the board to spend its entire budget of approximately $1.3 million within the first two months of operation. By the end of 1975, the ALRB had spent $5,268,571, requiring the state to consider a special appropriation of $3,795,034 just to keep the board’s doors open for business. The appropriation needed the approval of two-thirds of the state legislature and the signature of the governor. In addition, the board predicted a similar volume of activity in the 1976–77 season and requested a budget of $6.6 million, approximately five times the total approved for its initial operation.56

The success of the union and the cost of operation placed the ALRB in jeopardy as the legislature approached a February 1 deadline to approve the funding.57 Growers used the crisis as an opportunity to either push for reforms that would tip the scales back in their favor or dismantle the board altogether. Among their complaints, growers demanded the removal of Walter Kintz, whom they believed worked “in conspiratorial fashion with the UFW to assure victories for Chavez’s union.” Growers insisted on amendments to the law that mirrored conditions present in the National Labor Relations Act. Don Curlee, a spokesperson for the South Central Growers Association, petitioned for a provision available to employers under the federal law that allowed a company to seek decertification of a union when company officials believed the employees no longer wanted to be represented by a union for which they had voted in a previous election. Curlee also opposed the requirement under state law to hold an election within seven days. Joe Herman, attorney for the association, added the objections of most growers to the “make-whole remedy,” which required the agency to determine the pay for a worker when the employer was found to have bargained in bad faith. An Imperial Valley grower, Jon Vessey, voiced the common complaint among growers that the law failed to distinguish year-round employees from temporary workers in determining the eligibility of voters in union elections. Vessey complained, “That means that a few hundred people, working for me for just a few weeks, can, by majority vote, decide which union, if any, my year-round workers want, even though the year-round people are those on whom we are most dependent.” Although the association demanded that such procedures be changed, the majority of their efforts went toward lobbying state senators to block funding for the ALRB rather than to reform it.58

In spite of appeals by board chairman Roger Mahoney and general counsel Walter Kintz to pass an emergency appropriation to keep the agency open until the next legislative cycle, a coalition of Republicans and farm-area Democrats voted against it. At the time of the vote, the UFW had won 55 percent of the ALRB elections, compared to 34 percent for the Teamsters, 5 percent for other unions, and 6 percent for no union at all. In addition, as the harvest and voting moved to the Imperial Valley, the UFW had built momentum, putting together a string of eleven victories compared to just one for the Teamsters since December 1. The failure to pass the appropriation bill stopped the UFW from accumulating more victories and forced the agency to lay off all but thirty of its 175-member staff.59 By February 6, the ALRB had all but ceased to exist.

Cesar Chavez responded to the crisis by turning to the trusted strategy of picket lines in the fields and in front of markets. “[This is a] day of infamy for farm workers,” he declared. “Our only recourse is to take our cause to the people of California and return to strikes and boycotts.”60 As the reality of the agency’s closure hit rural California, the labor situation returned “to the law of the jungle.” Predicting that the violence had just begun, Chavez made the tactical move of exporting the struggle to the urban marketplace, announcing a boycott of Sun Maid raisins, Sunsweet nuts and processed fruits, and products backed by eight Fresno packinghouses that had played a significant role in defunding the ALRB.61 “We’ll beat them with the boycott and pin them to the wall,” Chavez angrily told reporters, predicting, “They’ll come back to Sacramento crying for the money (to reactivate the board).”62 This time, however, the growers stood firm, aware that the union had directed many of its resources away from the boycott toward elections. Whether Chavez and the union admitted it, the hard-fought victories in secret ballot elections had shifted their priorities from pressuring growers in the marketplace to achieving collective bargaining through the farm labor law. As the defunding crisis prevented the UFW from making gains during the 1976 harvest, the union focused on a new strategy: reviving the ALRB through the California initiative system.

A TOUGH GAME OF CHICKEN

At the same time Chavez announced the renewal of the boycott, the UFW also filed an initiative proposal for the fall ballot in California. During the early twentieth century, progressive reformers in the Golden State had added three revolutionary electoral procedures—the recall, the referendum, and the initiative—that provided a degree of direct democracy to voters. By a majority vote, the electorate could recall an elected official, invalidate an established law (referendum), and circumvent the state legislative process and create a new law (initiative). These measures had come about as a reaction to the excessive influence of railroad moguls during the Gilded Age. By the mid-twentieth century, however, these progressive reforms had become the tool of powerful interest groups who achieved a variety of goals, especially through the use of the initiative (more commonly known as the proposition). By the 1970s, conservative groups had gained the upper hand in controlling an initiative system in which qualifying a proposition became more challenging.63 Between 1970 and 1976, only fifteen initiatives out of ninety-six proposals received enough signatures to make it on the ballot. Of those fifteen, only four passed, with only two considered by the UFW executive board as consistent with their political beliefs. During the board meeting to discuss the decision, Chavez acknowledged, “Many people vote no on an issue because they feel that is the safe thing to do.” Unfortunately for the union, they would be asking the public to say yes when statistics showed that a no vote had an 8 percent advantage among voters. Such history and statistics notwithstanding, the initiative system provided a well-organized union such as the United Farm Workers the possibility to achieve its legislative goals through popular vote. Chavez expressed confidence in their ability to obtain at least a 60 percent margin of victory if they appealed to the California electorate to create a new, improved farm labor law more to the union’s liking.64

The situation in the fields and on the board went from bad to worse, as new disputes broke out on Imperial Valley farms and three of the five members on the ALRB resigned. In April 1976, LeRoy Chatfield quit the board to work on Governor Brown’s presidential campaign. Two other board members, Joseph Grodin and Joseph Ortega, both seen as appointees favoring the UFW, resigned, leaving its chairman, Bishop Roger Mahoney, and the growers’ representative, Richard Johnsen Jr. Within ALRB offices, a skeleton crew held on without pay in hopes that legislators would reach a compromise to fund their operations. As the growers dug in and the UFW adopted the initiative strategy, hopes of a legislative solution dimmed, and government agents began to peal off. By mid-April, the embattled general counsel, Walter Kintz, announced his resignation, calling the ability of a small minority of senators to kill funding for the ALRB a “travesty of justice.” “Emotionally and professionally,” Kintz reported, “I could not tolerate sitting around any longer while the Legislature debates all over again whether or not it wants a farm labor bill.” He threw his support behind the UFW initiative, which garnered enough signatures by May to make it onto the November ballot as Proposition 14.65

Proposition 14 dealt with the immediate problem of funding, although the union also sought to change the farm labor law in ways that strengthened its ability to win more elections. Advocates of the original law complained about the ability of one-third of the senate to block funding; as a consequence, the initiative proposed to mandate that the legislature provide appropriations necessary to carry out the purpose of the act without interruption. The initiative would replace the current law with another that mirrored the ALRA by setting up a government-supervised election system that would allow farm workers to decide by secret ballot which union, if any, they wanted to represent them. The initiative also added a few key changes, which drew the ire of the growers and support from labor unions, including the Teamsters. Under the ALRA, unions and employers frequently disputed the number of employees eligible to take part in an election largely because the employer dictated when and how a list of employees would be submitted to the agency. Surprises in the size of the workforce and challenges to the list from unions often resulted in unfair labor practice claims that delayed the results of elections. The initiative would empower the new ALRB to decide under what circumstances a union could receive a list of workers from the employers. The new law would increase the punitive powers of the ALRB, allowing the agency to impose triple damages against a grower or a union found guilty of unfair labor practices. It would also require those opposed to an already certified union to get 50 percent of the workers to sign cards saying they no longer wanted such representation before an election could be held. Finally, the initiative addressed the thorny issue of union access to workers on California farms during elections. The initiative sought to write into the law an “access rule” that required growers to permit union representatives on their property one hour before work, one hour after work, and at lunch time.66 The director of the “Yes on 14” campaign, Marshall Ganz, simplified the union’s argument for the rule change as “an access to information” issue. “If you are going to have free union elections,” he explained, “the workers must be fully informed.”

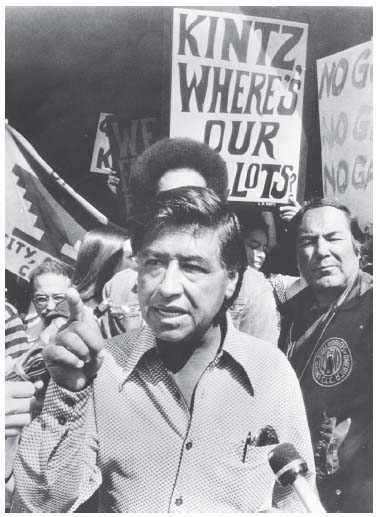

FIGURE 12. Cesar Chavez at an unidentified United Farm Workers rally, 1971. Behind him stands a man in a United Steelworkers of America jacket. ALUA, UFW Collection, 3223.

Chavez believed the boycott and the positive press during union elections would translate into support for the UFW at the ballot box. Although some members had doubts about the ALRA’s effectiveness, Chavez, union organizers, and the UFW legal department had succeeded in turning the farm labor law into a political coup. By the time the ALRB shuttered its doors, the United Farm Workers had won a majority of elections and enjoyed momentum in the Imperial Valley in anticipation of the 1976 harvest. Negative stories in the media regarding labor strife in the fields once again focused on Teamsters’ acts of treachery or growers’ resistance to farm worker justice. The continued observance of the boycott by consumers showed the UFW’s appeal to the general public and the potential for the union’s urban network to deliver a “Yes on 14” message to California voters. Some members questioned the strategy. Esther Padilla remembered, “There had been a lot of discussion within the executive board [about not pursuing the proposition] because you’re talking about making people in the cities think we’re going to invade their private property.”67 Chavez, however, insisted that they could win and ordered all resources to be directed toward the “Yes on 14” campaign.

In his announcement of the union’s initiative strategy, Chavez anticipated the considerable cost of the campaign for both sides. “The Farm Worker Initiative campaign will be difficult and expensive,” he anticipated, forcing the growers to spend millions to defeat it and requiring farm workers to “sacrifice themselves and their time” to achieve victory. “We will match their millions,” he promised, “with our bodies, our spirits and the goodwill of the people of this state.”68 Within a week of his announcement, Chavez had redirected most of the funding and staff from the boycott houses to an all-out effort to pass the initiative. Walter Kintz, in his assessment of the strategy, called the decision a “tough game of chicken,” suggesting that the initiative drive challenged growers, the UFW, and ultimately the voters to resolve the funding of the ALRB once and for all.69 In the interim between exhausting the ALRB budget in February and the start of a new fiscal year in July, the governor replaced Kintz with Harry J. Delizonna and named three new members to the board, but could do nothing to provide long-term funding. UFW leaders maintained a high level of confidence in their ability to persuade voters to resolve the matter by supporting the initiative.

The union’s position underestimated the growers’ ability to adapt. Growers had become wise in their previous battles and made a number of key decisions to strengthen their appeal to voters, perhaps the most important of which was to mobilize and unify their community into an organization of thirty-two farm groups representing both large corporate farms and small family farmers. Chaired by a fifty-three-year-old Japanese American farmer, Harry Kubo, the Ad Hoc Committee discussed the best way to combat the farm workers’ initiative and began a fundraising effort.70 Don Curlee, spokesperson for the South Central Farmers Association, spoke glowingly of the ability of the agricultural community to raise money for the new growers’ organization, commenting, “I am flabbergasted at [their] eagerness to respond financially.” Fred Heringer, president of the California Farm Bureau, shared his goal of raising between $2 and $2.5 million, and Les Hubbard of the Western Growers Association used his organization’s newsletter to gather a minimum of $100 to a maximum of $10,000 from each of his readers. In addition, the Associated Produce Dealers and Brokers of L.A. Inc. and the Council of California Growers broadcast their appeal for contributions to the committee’s war chest through their members-only monthly newsletters. In the end, Kubo and his colleagues garnered donations from a who’s who of the California business world, including Southern California Pacific, Superior Oil Company, Pan American Insurance Company, California Farm Bureau, Irvine Land Company, Newhall Land Company, Weyerhaeuser Paper Company, the Western Growers Association, and Tenneco. This coalition gave growers the resources to challenge the “Yes on 14” campaign with a barrage of television and radio ads.71

At the first few meetings of the Ad Hoc Committee, Kubo distinguished himself as a credible voice on farm labor issues. “[Kubo’s] not polished and he’s not a professional,” one unidentified leader of a statewide farm group told a reporter, “but he knows what he’s talking about and he knows how to tell it to the people.” The local newspaper took note of Kubo’s rags-to-riches story, deeming him “the ineloquent speaker-turned-spokesman” for all farmers.72 His handle on labor issues that confronted a wide spectrum of the agricultural community, from large-scale farmers to small family farmers like himself, provided useful cover to corporate entities who had become easy targets for derision in the David-and-Goliath struggle. Seeking greater organization and a more sustained campaign, the Ad Hoc Committee chose to form a “No on 14” organization, Citizens for a Fair Farm Labor Law, and named Harry Kubo as their president.

Growers’ organizations understood that economic superiority constituted only half the battle, given their defeats during the 1970 boycott. The ability of Citizens for a Fair Farm Labor Law to craft an appeal that resonated with voters behind a credible spokesperson showed a degree of savvy in a decade-long struggle to control labor conditions in rural California. At first blush, Kubo was an unlikely representative for growers. Like many Japanese American farmers, he had spent much of his life in rural California as an outsider to the European American–dominated grower networks. The Kubos’ family farm in Parlier in fact was their second after Harry, his parents, and his siblings were placed in an internment camp at Tulare Lake in Modoc County, California. After leaving the camp, the Kubo family worked in Sanger, California, as field workers for 75 cents per hour. In 1949, they pooled their earnings and purchased a forty-acre grape and tree fruit ranch. While the family worked the homestead, Kubo and his brothers continued as farm workers to pay off the mortgage and raise money to buy an additional sixty acres. By the mid-1950s, the Kubos had accumulated 110 acres in the Parlier-Sanger section of the San Joaquin Valley and eventually acquired 210 acres by 1976.73

Kubo’s entry into the battle owed as much to UFW tactics as it did to the vision of wealthy growers. After the UFW had signed contracts with most San Joaquin Valley grape growers in 1970, a small group of independent family farms constituting 15 percent of the market remained outside of the grower-union accord. In an initial effort to corral these farmers into contracts, the United Farm Workers picketed eight packinghouses handling their fruit and approximately seventeen farms throughout Tulare and Fresno County. Japanese Americans owned fourteen of the seventeen fields picketed, including the Kubos’ small farm.74 During the conflict, tension erupted into occasional acts of vandalism, including slashed tractor tires, nails and spikes in driveways, arson-caused fires, and yearling trees cut down at the trunks. Larry Kubo, Harry’s son, remembered one incident in which a number of young UFW picketers entered the Kubo farm at night: “I was fourteen, and they ran on to our property and started screaming and yelling at us, and they were not much older than me.” In their exuberance, the group vandalized the Kubo tractor. Through it all, Harry kept his family inside and told his son to “stay where you’re at” until the group passed.75

Such encroachments on their property inspired Harry Kubo to action. “In 1971,” he told a reporter, “I saw fear in the farm workers’ eyes and I thought it was unjust.” When he shared his concerns with workers and fellow Japanese American farmers, both gave him the same message: “Why don’t you do something about it?” Reflecting on the moment, Kubo recounted the impetus for his activism: “The general thinking was that the entire government is built on equality, yet we weren’t doing anything to preserve these basic rights for ourselves or our workers. We felt something should be done and someone should help the unassuming farmer and those who don’t like to speak out.”76 Together with fellow Japanese American growers Abe Masaru and Frank Kimura, Kubo organized the Nisei Farmers League and became the organization’s first chairman. The league began with twenty-five neighboring farmers; under Kubo’s leadership, it grew to 250 members within a year. By 1976 the league had swelled to more than 1,400 members, of which, surprisingly, only 43 percent were of Japanese descent.77

Chavez and the “Yes on 14” advocates viewed Kubo’s involvement as a cynical ploy by wealthy growers. Throughout the campaign, Chavez emphasized the $2.5 million budget of his opponents, which they used to hire “experienced manipulators of public opinion” who tried to “persuade a lot of people that passage of Proposition 14 will give the right to Mexican farm workers to enter their homes without permission.” Such allusions to fears of home invasion never directly entered into Kubo’s vocabulary, but growers employed Janice Gentle, president of the Central Valley Chapter of California Women for Agriculture, to make them. Gentle articulated the familiar concern of “allowing union organizers uninvited entry onto farm property three times a day” without explaining the context of their visits. She went further by asking the question “Why is it that a person who grows our food should be denied the same rights to his property that you and I currently have simply because we or our spouses work in construction, in a financial institution, or in a factory?”78 Gentle’s conflation of rural agriculture with industries that employ mostly white workers conveniently ignored the racial fault lines in rural California that were well known to the public. Such a conflation invited urban and suburban voters to imagine their homes or workplaces being overrun by Mexican workers, a specter that benefited the anti-14 forces.79

Kubo, however, remained focused on the consequences of the rules change to farmers and farm workers. He worried, “You kick an organizer off the farm for being disruptive … and the next day the guy is back on your farm and you have to let him enter and he can disrupt things all over again.” Kubo believed, “Under ‘14’ the worker would just about lose his right to work or not work under a union contract. The union could bring such pressure on him … he’d have to join even if he didn’t want to.”80 In his rebuttal, Chavez ignored nuances in the anti-14 position, inserting a not so subtle jibe at Kubo’s credibility by asserting that agribusiness had “already started a slick campaign … using a small grower as a front, presenting Proposition 14 as a violation of property rights.”81 Kubo rarely if ever criticized Chavez’s character in public, but in his oral history, he shared his impressions of the labor leader after they met in 1974. “My first impression of him,” he told his interviewer, “was a person that was very arrogant … but I also found that he was a very intelligent man, a person with total dedication to the cause that he was pursuing.” Kubo maintained an abiding respect for Chavez, acknowledging that their “roots are the same” and that they shared a commitment to improving farm workers’ lives.82

Although advocates for Proposition 14 refused to acknowledge it, Kubo’s concern for private property rights stemmed from his experience in World War II. Like other Japanese Americans, Kubo saw the internment as “a black mark in the history of the United States” and vowed to “do everything in [his] power to disseminate and tell the people what happened in 1942” so that “it will never be repeated.”83 For Kubo, allowing the ALRB to dictate the terms of workers’ access to private property harkened back to a dark period for him, one that included the interruption of his education at a community college, the undoing of eighteen years of hard work as a sharecropper, and ultimately the dispossession of private property that the family had worked hard to acquire. In his 1978 oral history, Kubo painfully recounted how local whites whom he referred to as “vultures” offered to buy appliances at severely discounted prices from his family when they were evacuated to an Assembly center in Arboga, California. “It took a lifetime to buy those things,” he explained, “and they were offering my parents for the refrigerator and the washing machine two dollars, a dollar and a half, five dollars, and my father said, ‘well, even if we had to throw it away, we wouldn’t give it to them.’”84 Fortunately for the Kubos, the Leak family, which owned the property they sharecropped, safeguarded most of their possessions and sent the family’s portion of their earnings to them at the Tulare Lake in Modoc County, California where they spent the remainder of the war in an internment camp.

The kindness of the Leak family notwithstanding, the traumatic experience made Kubo distrustful of the government and vigilant about protecting his rights. For Kubo, the loss of appliances symbolized a loss of freedom associated with a life of farming, an occupation common among many Japanese Americans living in the Central Valley and the primary vehicle for achieving economic success for Nisei in California.85 The position of “Yes on 14” advocates who saw the private property rights argument as disingenuous failed to appreciate how, for Kubo at least, such concerns were based in an experience of state oppression.

The cities became the battleground for Proposition 14, with both the UFW and Citizens for a Fair Farm Labor Law investing much time and money into winning the war of ideas among these large blocks of voters. Kubo traveled more than 30,000 miles and organized highly visible “No on 14” rallies in Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area, and San Diego in the week prior to the election, drawing as many as 4,000 participants at each event.86 He orchestrated successful door-to-door campaigns that rivaled the UFW’s supremacy in grassroots outreach and conducted media events, complete with a country-western music concert that inspired supporters to attend rallies throughout the state. He honed the position of the growers to an easily digested message, “Protect Private Property—No on 14 Committee,” that the public understood and editorial boards of several urban newspapers and television and radio stations picked up and incorporated into their opinions on the subject.87 These efforts gave the growers an unprecedented voice in the cities and helped raise political contributions that supported an increased presence of campaign ads on the airwaves.88

The union countered these events with an aggressive grassroots campaign of its own. In Los Angeles, for example, the community organization Coalition for Economic Survival worked on behalf of the union to challenge the private property argument as “the old ‘big lie’ campaign.” “They have poured millions into a demagogic ‘vote no’ campaign,” its steering committee wrote to its members, “using the phony ‘private property’ slogan.”89 As the election neared, Chavez’s attack on the validity of the private property argument became more urgent. In a speech to 800 supporters in National City, he implored the partisan crowd not to take victory for granted and urged everyone to assume individual responsibility for challenging the growers’ attempt to confuse voters. “We’ve got to tell the people that [the private property argument] is a phony issue,” he warned, “or we’re in trouble.”90 In many posters and fliers throughout the months leading up to the election, the UFW routinely drew attention to Kubo’s private property argument as “the Big Lie” and republished articles identifying the wealthy growers who had contributed to Citizens for a Fair Labor Law.91 The union also highlighted the many politicians whom they counted as allies, including President Jimmy Carter, Governor Jerry Brown, Mayor George Moscone of San Francisco, and Mayor Tom Bradley of Los Angeles. In return, the UFW endorsed the candidacy of any politician who supported Proposition 14, including a very public endorsement of Jerry Brown for president when Cesar Chavez introduced him as a candidate at the Democratic National Convention in New York City.92

FIGURE 13. Governor Jerry Brown of California visits with Cesar Chavez and members of the United Farm Workers at LaPaz, Keene, California, 1976. ALUA, UFW Collection, 292.

In the end none of these endorsements helped the union. Voters handed the UFW a crushing defeat, rejecting Proposition 14 by a better than three-to-two margin on November 2, 1976. The “No on 14” forces garnered more than 2 million more votes than advocates for the initiative and carried fifty-six of the fifty-eight counties in the state, with Alameda and San Francisco the only two counties voting in favor.93 Although the growers’ newsletter interpreted the outcome as “a repudiation of the naked power grab of Cesar Chavez” and “a major defeat for Governor Gerald Brown,” Kubo offered a more sanguine evaluation, highlighting the importance of the organizing drive: “[It was] amazing to see the grassroots response from agriculture. People we didn’t know were out there came to the front and pitched into the effort to defeat this bad initiative. It was this all-out support that made the victory possible.… Every grower—all of agriculture—can be proud of this accomplishment.”94 Union organizers tried to attribute the outcome to the growers’ $2.5 million budget, but in the end the UFW spent $1.3 million of its own. To add insult to injury, the “No on 14” campaign ended the year with a surplus of $29,750, whereas the United Farm Workers showed a deficit of $218,448.95

The defeat forced Chavez and the union to reevaluate their assumed influence on the public. The appeal of the boycott to citizens had built an expectation that the union could always paint its opposition as exploitative and that consumers would always side with the farm workers. Indeed, the decision of the executive board to redirect the boycott network in the service of promoting Proposition 14 signaled such faith. Their defeat might be explained by the substantial media budget raised by growers, although the magnitude of the loss suggests other reasons for the one-sided victory by the “No on 14” campaign.

Support for Kubo’s message manifested common ground between him and voters on the sanctity of private property in California. The electorate’s decision was consistent with an entrenched preoccupation with the rights of property owners, clearly articulated in the repeal in 1964 of the fair housing law known as the Rumford Fair Housing Act. During the civil rights movement, the California Assembly had passed the law named for William Byron Rumford, the first African American elected official in northern California, that prohibited discrimination in most privately financed housing and outlawed racial discrimination by home lenders. In response, a coalition of the California Real Estate Association, the Home Builders Association, and the Apartment Owners Association organized a successful campaign to overturn the law by way of an initiative—coincidentally, also Proposition 14—that passed by a two-to-one margin. Racism clearly played a role in the vote, but many voters also expressed their opposition to what they perceived as the state interfering in the management of private property.96

Kubo’s role also signaled an important turn in the political strategy of the growers. Prior to their victory, they had attempted to discredit Chavez as a false prophet, the UFW as a social movement rather than a union, and the Teamsters as the superior choice for workers. None of these strategies worked. In Kubo, however, they found a sympathetic character whose life story successfully countered the appeals of the UFW. By 1976 much of the public accepted the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II as an injustice and saw Kubo as a victim of the misguided Executive Order 9066, which initiated the government action. Indeed, within two years, the Japanese American Citizens League believed it had enough of the public’s sympathy to launch a reparations movement.97 Kubo’s history gave him increased credibility with the public and enabled him to articulate a political position that questioned the state’s right to determine who could enter private property. One of the most effective images of the “No on 14” campaign was a poster of Kubo standing in front of his home with the following message in bold letters: “Thirty-four years ago, I gave up my personal rights without a fight … IT WILL NEVER HAPPEN AGAIN.”98 This evocation of internment paid tremendous dividends for growers who, ironically, now relied on an act of racial injustice to stem the UFW’s momentum.

UFW officials tried to draw attention to the inconsistencies between Kubo’s life and the growers’ position; however, the fact that voters bought Kubo’s story made all the difference in the defeat of Proposition 14. The failure of the initiative ended the union’s dream of rewriting the labor law and securing full funding for the ALRB, even though the California legislature continued to earmark funds for it. Indeed, workers continue to clamor for elections, and the growers braced for another contentious year in 1977. In response, some UFW organizers and executive board members prepared for elections. Eliseo Medina, for example, set his sights on addressing citrus workers’ desires for an election in Ventura, while Marshall Ganz and Jessica Govea strategized on how to organize lettuce workers in the Imperial Valley who were denied elections as a result of the funding crisis.

The real cost of the ballot measure’s defeat lay in the changes the campaign wrought on UFW strategy and Cesar Chavez’s psyche. Chavez’s decision to suspend the boycott in the service of the “Yes on 14” drive interrupted what had been an effective tool for the union. In the wake of the defeat, the union confronted a morale problem that rippled throughout its ranks, from Chavez to the many volunteers who campaigned for Proposition 14. In anticipation of the vote, Chavez characteristically started an eight-day fast to influence voters. When the news of Proposition 14’s defeat broke, he ended his fast abruptly, eating so much at an election-night party that he made himself sick. On the drive home, he asked his assistant, Ben Maddock, to stop the car, got out, and sobbed on the side of the road for more than an hour. “It was a most awful time,” Maddock recalled. “We were not used to having an election and losing like that.”99

Those closest to Chavez remembered that he took the defeat personally and began to descend into erratic behavior. Esther Padilla believed that “Cesar lost it after Prop 14”: “I think he had a break down. He just couldn’t believe that Cesar Chavez, this icon he had become, would lose an election.” Ganz, who had been in the fields campaigning for Proposition 14, came back to find Chavez “really shaken up about [the loss]” and beginning to get “into some strange stuff.” Ganz remembered, “He’s doing mind control, he’s doing healing, he’s starting to talk about conspiracies.”100 During the “Yes on 14” campaign, Chavez made many trips to Los Angeles, striking up friendships with a number of Hollywood actors, including Valerie Harper from The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Rhoda. According to Gilbert Padilla, Harper introduced Chavez to mind-control experts, including “mentalist,” Bruce Bernstein, and Tejano parapsychologist and author, José Silva, who espoused a belief in extrasensory perception, the ability to communicate without speech or physical gestures. Padilla witnessed Chavez’s “shift in personality” and raised the issue quietly among friends, but at the time union members and volunteers were so involved in their own tasks that few noticed the change.101 According to Esther Padilla, Chavez had a difficult time owning his decision to channel the union’s resources into a losing battle. She remembered, “He had to blame somebody for the failure of Proposition 14.”