CHAPTER 10

The Anti-Communist Police State

“The country is literally in the grip

of a police regime and a private terror.”

—American Civil Liberties Union chief Roger Baldwin1

After 1953, the movement for liberty and equality in the north deferred plans to exercise sovereignty over all of Korea and concentrated on defending itself against the hostility of Washington, which remained committed to the objective of rolling back communism in Korea. For the movement in the south as well, the primary task was to survive. From the very first moments that Koreans had fought for freedom from foreign domination and exploitation at home, they had met the fierce resistance of traitors backed by empires—Japan, until 1945, and the United States thereafter. Collaborators with the Japanese empire quickly became collaborators with the US empire. In 1960 there remained approximately 600 KNP officers, the main instrument of anti-communist suppression, who had served the Japanese. Nearly all were in senior positions.2 Because the aims of the ROK were antithetical to the goals of national and social revolution which, as indicated above, inspired most Koreans, the South Korean state had to become—and was from its birth to the present—a very strong police state, with all the trappings of one: military dictatorship, extreme ideological control, a security police force recalling the Gestapo, concentration camps for leftists and their extermination during periods of crisis, designation of all socialist countries as enemy states, and a draconian anti-Left National Security Law which locked up Koreans for even sympathizing with the DPRK.

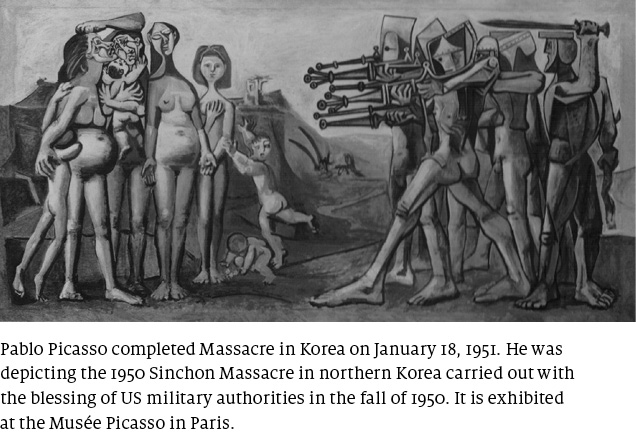

Joan Robinson had remarked that in the mid-1960s the ideological control of Koreans of the south was so extreme that no “Southern eye can be allowed a peep into the North.”3 Until 1973, Kim Il-sung’s photograph was banned from publication in the ROK. South Korean censors combed through foreign publications, redacting photos of Kim with splotches of black ink.4 Kim, whose contribution to the project of liberating Korea was second to none, was demonized by ROK authorities and traduced. South Korean security agencies disseminated the myth that the DPRK leader was not, in fact, Kim Il-sung, but an imposter beholden to the USSR who had stolen the famed guerilla leader’s identity. Immersed in anti-DPRK slanders, Koreans had no real conception of who Kim Il-sung really was. In 1989, Suh Dae-sook, South Korea’s leading scholar of Korean communism, was granted leave to finally tell the true story of Kim Il-sung. A large audience of South Korean youth erupted in applause when Suh explained that Kim was a hero of the guerilla struggle for Korean independence, this revelation being completely new to them.5 So militantly anti-leftist is South Korea that “a brand of crayon called Picasso was once banned because of the artist’s Communist associations,”6 explained Choe Sang-hun, the New York Times’ Korea correspondent. In 1951, Picasso, a member of the French Communist Party, painted a famous work, Massacre in Korea, which depicted the slaughter of Korean civilians by anti-communist forces during the Korean War. The ROK authorities didn’t take kindly to their atrocities becoming the subject of a famous artwork—and by a communist no less!

The ROK police state has cracked down, with varying degrees of intensity over the years, on virtually every public expression of leftism, including anti-capitalism, anti-colonialism, and anti-imperialism—in other words, all genuine expressions of unalloyed liberalism. What the historian Arno J. Mayer said about Hitler, namely, that he abhorred communism because it “was the final culmination and distillation of the Enlightenment”7 can equally be said about the animus of the South Korean state and its US sponsors toward Korean communism.

Some degree of intolerance of leftist dissent is emblematic of all states in capitalist societies, and the ROK is assuredly a capitalist state; that’s the way it was designed by its creator, the United States, even if most Koreans wanted a socialist state. But in Washington, where billionaire investors carry the day, the political views of Koreans are of no consequence. As a US secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, once famously remarked in connection with Chile: “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.”8 Kissinger was echoing Woodrow Wilson, whose rhetorical commitment to self-determination was matched only by his actual commitment to overthrowing foreign leaders he didn’t like, even if they happened to be elected by their own people. Wilson would stop intervening in other people’s countries, he said, if only they learned to “elect good men.”9 For the United States, good men meant anti-communists like Syngman Rhee rather than communist national liberation leaders like Kim Il-sung.

Even in self-declared liberal democratic societies, which are erroneously believed to tolerate dissent to a higher degree than other societies, the security services have had a long history of surveillance against those who challenge the rich and powerful. The history of the political police in such societies is one of conservatism where the targets of surveillance are militant leftists who challenge the status quo. Those who pursue the class war from the bottom are regarded as subverting the established political and economic order and therefore are deemed legitimate subjects for surveillance and disruption.10

The ROK anti-communist police state differs from that of other capitalist countries in degree only, the difference due to its daily confrontation with the DPRK, which embodies genuine Enlightenment values, and which, in its rejection of foreign domination, acts as an inspiration to many Koreans of the south. It’s virtually impossible to be committed to anti-imperialism and convinced there’s a better alternative to capitalism without espousing values that significantly overlap those of the DPRK. Consequently, it’s virtually impossible for South Koreans who embrace any kind of commitment to authentic Enlightenment values not to be accused of being a DPRK fellow traveler, and therefore of transgressing the National Security Law.

Consider the platform of the Unified Progressive Party (UPP), a leftist party founded in 2011, which was dissolved in 2015 by the ROK’s Constitutional Court on the ground that its goal was “North Korea-style socialism.” The party sought an end to the US military presence in Korea (as does Pyongyang) and advocated an end to Korea’s subordinate relationship to the United States (another DPRK demand.) The party talked of “rectifying” Korea’s “shameful history tainted by imperialist invasions, the national divide, military dictatorship, the tyranny and plunder of transnational monopoly capital” and large family-owned conglomerates, like Samsung and Hyundai11—also DPRK positions.

UPP members were widely denounced by conservatives as jongbuk, a derogatory term denoting followers of the DPRK accused of spreading subversive ideas challenging the merits of capitalism and the ROK’s subordinate relationship to the United States.12

The centerpiece of South Korea’s anti-communist police state is the notorious National Security Law, created by Syngman Rhee in 1948 to criminalize communism, or more precisely, the DPRK, the embodiment of Korean communism, and to criminalize its many supporters, which included the bulk of Koreans, before decades of ROK brainwashing produced an epistemology of ignorance. Criticized by Amnesty International,13 Human Rights Watch,14 and the United Nations,15 the National Security Law has been variously used to lock up South Koreans for any expressions of leftism.16 South Koreans have run afoul of the law for making comments that were construed as supportive of the DPRK, setting up websites with pro-DPRK content, calling for the establishment of a socialist state, discussing alternatives to capitalism in public forums, re-tweeting messages from the DPRK’s Twitter feed, possessing books published in the DPRK, listening to radio broadcasts from Pyongyang, and visiting the DPRK without Seoul’s permission. Promoting conciliation between the two states has also been punished under the law.

In the 1970s, the poet Kim Chi-ha was jailed because his poems advocated “class division.” In 1976, South Koreans who signed a declaration commemorating an uprising against Japanese rule were imprisoned, under the provisions of the law. In 1987, a publisher was arrested for distributing travel essays written by Korean-Americans who were sympathetic to the DPRK. The law has been used to jail university students for forming study groups to examine DPRK ideology. In 1989, the ROK police state arrested an average of 3.3 citizens per day for infractions of the anti-communist regulations. In the first half of 1998, more than 400 were arrested under National Security Law provisions for demonstrating against unemployment. In 2001, sociology professor Kang Jeong-koo was jailed for visiting the birthplace of Kim Il-sung while on a visit to the DPRK.17

One man was convicted of having in his possession “printed matter aiding the enemy.” The offending material included E.H. Carr’s The Russian Revolution, Maurice Dobb’s Capitalism Yesterday and Today, Eric Fromm’s Socialist Humanism, and Paul Sweezy’s Theory of Capitalist Development.18 In 2007, Kim Myung-soo was confined to a jail cell so small “he could spread his arms and touch the facing walls.” His crime: aiding the enemy by operating a website that sold Edgar Snow’s Red Star over China, a biography of Karl Marx, and other titles deemed to be pro-DPRK.19 In 2008, ROK military personnel were banned from reading Bad Samaritans: The Secret History of Capitalism by Chang Ha-Joon (Chang is no Marxist, just critical of capitalism), Noam Chomsky’s Year 501: The Conquest Continues, and Hyeon Gi-yeong’s novel A Spoon of the Earth, all of which were labeled subversive books under an order that banned pro-DPRK, anti-capitalist, and anti-US publications.20

If Seoul suppresses books, it no less vigorously wipes out online content it doesn’t want South Koreans to see. According to the New York Times, “When a computer user in South Korea clicks on an item on the” DPRK “Twitter account, a government warning against ‘illegal content’ pops up.”21 In 2011, ROK authorities blocked over 53,000 Internet posts for infractions which included having a kind word to say about the state founded by Kim Il-sung.22 In the same year, the ROK deleted over 67,000 web posts that were deemed favorable to the DPRK or which criticized the US or ROK government. Over 14,000 posts were deleted in 2009.23

In August 2011, Prosecutor General Han Sang-dae “declared ‘a war against fellow-travelling pro-North Korean left-wing elements,’ and said, ‘We must punish and remove them.’”24 The government kept Han’s promise, disbanding the left-wing UPP, stripping its legislators of their parliamentary seats, and jailing a handful of its members, including the lawmaker Lee Seok-ki. Lee was convicted under the National Security Law for, among other things, singing the Song of the Red Flag. The song is a socialist anthem, but so anodyne that even members of the British Labor Party occasionally sing it at party meetings. Another of Lee’s transgressions was his calling Korea “Chosun,” the country’s last official name before colonization by Japan, and the DPRK’s autonym for the country; in contrast, the ROK denotes Korea as Hanguk. The ROK police state regards Chosun as a pro-DPRK shibboleth.25

Conservatives and liberals have vociferously criticized jongbuk, accusing them of spreading subversive ideas and worming their way into positions of influence. Lee rejoined that jongmi, blindly following the United States, is a problem of far greater magnitude.26 Lee was also accused of calling, at a closed meeting, for the sabotage of South Korean infrastructure in the event of war with the DPRK. He was convicted of inciting an insurrection and sentenced to a nine-year jail term, just one of hundreds of thousands of Koreans who have, since 1905, been locked up for promoting Korean independence and socialism.

While Lee’s case was before the courts, the ROK government referred the UPP to the Constitutional Court, asking for the party’s dissolution, owing to its program mirroring the aims and values of the DPRK. The government called the UPP’s commitment to “overcoming foreign domination and dissolving” the ROK’s “dependence on the alliance with the US,” as well as its defining South Korea as “not a society where the workers are master, but the reverse, where a privileged few act as masters,” as being “identical to the argument coming from Pyongyang,”27 which indeed it was. The court accepted the government’s brief, ruling that the UPP sought to undermine South Korea’s liberal democracy (hardly a fitting description of a pro-imperialist police state) and its goal was to establish DPRK-style socialism. Far from seeking to undermine an authentic liberal democracy, the UPP was actually seeking to create one. A liberal democracy, by any unbiased definition, unaffected by an epistemology of ignorance, would look exactly like the system Lee advocated: one committed to freedom (from foreign domination and exploitation in the workplace), equality (of nations and individuals) and the unity of humankind (rather than peninsular division to suit the geopolitical goals of a foreign hegemon), i.e., liberté, égalité, fraternité—the liberal democratic goals of the revolution inaugurated in 1789, carried forward by the revolution of 1917, and advanced during the great twentieth century wave of decolonization

President Kim Dae Jung used the law to arrest people who demonstrated against unemployment and the government’s response to an economic crisis. He also used it to arrest the filmmaker Suh Joon Sik, who screened Red Hunt, a film about anti-communist suppression on Jeju Island in 1948, at the Korean Human Rights Festival in 1997. But Kim refused to prosecute Hyundai Business Group for clandestinely giving nearly $200 million to North Korea, a blatant violation of the law’s prohibition against knowingly providing monetary benefits to the DPRK.28

Conservatives believe that the law and its enforcement are necessary to prevent political unrest, an acknowledgement that Koreans of the south remain committed to the emancipatory goals of the DPRK’s political program, and that absent the threat of punishment for overtly espousing these values, South Koreans would mobilize to demand change. Conservatives insist that the National Security Law must remain until North Korea abandons its ideology.29 In other words, so long as an ideology of liberation continues to be articulated by Pyongyang, the principal legal instrument of the South Korean police state must remain on the books to suppress the emancipatory movement of the south.

One South Korean newspaper editorial expressed the trepidation of conservatives this way: “What then would happen if we had completely abolished the National Security Law? There would be no legal way to block a South Korean citizen from joining the North’s Workers Party … Even if one established a [DPRK] ideology research institute … and instruct[ed] the ideology to students, nobody would be able to block it … Few citizens believe that our society is fully capable of digesting such confusions.”30

The National Security Law has not only been invoked to round up Koreans committed to prosecuting the class war from below, it has also been used to incarcerate Koreans who struggle for national self-determination. Kim Sun Myung served almost 44 years in an ROK prison for political crimes. He was 70 years old when he was finally set free. Kim served over four decades in jail because he was committed to Korea’s struggle for liberation. Despite being threatened with beatings and torture, he never recanted his communist beliefs, obstinately refusing to renounce his advocacy of Korea’s struggle for freedom, despite witnessing the fatal prison tortures of a number of comrades who defied demands to disavow their communism.31

Kim’s political journey began when Hodge landed at Inchon and refused to recognize the indigenously formed republic. Although an ROK citizen, Kim immediately joined the KPA when DPRK forces crossed the 38th parallel in June 1950, eager to participate in the Pyongyang-led project to unify the country and achieve its long sought-after independence.32

Kim’s active participation in the project came to an abrupt end on October 15, 1951, when he was taken prisoner. As a South Korean citizen who had joined the North Korean army, Kim faced capital punishment, but was sentenced to life imprisonment. Kim’s prison experience was austere. Placed in solitary confinement, without books or anyone to talk to, his verbal skills atrophied. Prison officials refused to treat his cataracts, leaving him blind. Kim’s immediate family members were harassed and threatened by ROK authorities; they never visited him, fearing their visits would place them at risk of further government harassment.33

In the 1970s, the anti-communist police state undertook a campaign to use corporal punishment and starvation to induce political prisoners to denounce the DPRK. Prison guards promised Kim meals, only if he renounced his beliefs. He chose hunger.34

Political prisoners who were thrown into the hell of ROK political prisons, and emerged, say that three factors stiffened the resolve of Kim and his ilk. First, their utter conviction that their cause was just. Second, the inspiration provided by Korean national heroes who had survived torture at the hands of the Japanese. And third, the dignity their resistance offered them, in a prison life otherwise lacking in dignity, where prisoners were forced to bathe in their own urine.35

Kim Suk Hyun, another Korean inspired by the DPRK, was released at age 79 after serving 32 years in jail for refusing to denounce North Korea. 36

On the day of his release, Kim Sun Myung was transported through bustling Seoul. Reporters were eager to find out how Kim would react to the vast changes that had transformed the capital city Kim had last seen four and a half decades earlier. Kim wasn’t awed.37 “It’s changed so much that I don’t recognize any of it,” he said, “But this kind of thing doesn’t impress me, because there are still a lot of poor people. These tall buildings are the labor of poor people. Did you ever see any rich people digging on a construction site?” Unbowed, Kim declared that the fight goes on.38

On the day Kim was released, two dozen DPRK sympathizers continued to languish in prison, each having served more than two decades in ROK dungeons.39 The unbowed conviction of Koreans like Kim Sun Myung, and the conservatives’ fear of what might happen if their compatriots are allowed to openly embrace the values embodied by the DPRK—indeed the very existence of the National Security Law—speaks volumes about the continuing attachment of Koreans of the south to the emancipatory goals that have always animated Korea’s fight for freedom.

* * *

In 1961, the same year the ROK government enacted an anti-communist law, declaring all socialist states enemies, the Korean Central Intelligence Agency, or KCIA, was founded. The KCIA operated, according to William R. Polk, “like the Gestapo. It routinely arrested, imprisoned and tortured Koreans suspected of opposition.”40

The KCIA was ubiquitous, infiltrating its agents into newspaper offices, radio stations, TV networks, political parties and discussion groups, trade unions, and classrooms, both in South Korea and abroad.41 KCIA surveillance was panoptic—its agents were everywhere, and watched everyone, all the time. So pervasive was KCIA spying, that South Koreans believed it was best to say nothing about politics to anyone, even loved ones.42 Had the ROK been communist, rather than capitalist, it would have been branded a “totalitarian” state of the very worst kind.

Recalling trade unions organized by the Nazi Party and Italian Fascists, the KCIA imposed a state-directed trade union structure on South Korean labor, creating workplace unions by sector. In August 1961, the KCIA appointed a committee to found a national labor federation comprised of twelve industrial unions. Labor leaders were required to pledge loyalty to the South Korean state. Once again, the label “totalitarian,” in the West, usually reserved as a term of vilification to be attached to communist countries, is a fitting description of a state in which the political police organized trade unions. Two years later, the state prohibited unions from engaging in political activity.43

George Ogle, an American United Methodist Church missionary, led a ministry for South Korean factory workers, whose hours were punishing and working conditions often hazardous. He helped found the Urban Industrial Mission, whose goal was to acquaint workers with their rights and offer advice on contract negotiations. When eight workers were arrested under the National Security Law, convicted of treason, and sentenced to death, Ogle sprang to their defense. This ultimately led to his deportation, but not before he was whisked to the KCIA headquarters for interrogation. Ogle was questioned for seventeen hours straight by Yi Tong-taek, chief of the KCIA’s sixth section. How could he possibly defend men about to be executed for treason as socialists, Yi demanded. Wasn’t he aware that one of the defendants “had listened to the North Korean radio and copied down Kim [Il Sung]’s speech?” The KCIA chief screamed,“These men are our enemies. We have got to kill them. This is war. In war even Christians pull the trigger and kill their enemies. If we don’t kill them, they will kill us. We will kill them.”44

The Agency for National Security and Planning, the successor to the KCIA, had in excess of 70,000 employees in 1998, not counting informal agents and spies, and a yearly budget of about $1 billion, making it the capitalist version of what the East German secret police, the Stasi, was reputed to be, to say nothing of its being a first cousin of the Gestapo. On top of its omnipresence in the mass media, political groups, universities, and trade unions, it also controlled organizations that publish well-placed English-language academic journals.45

* * *

The movement against foreign domination of Korea and for what the historian Hakim Adi calls a “people-centered” economy46 was strong enough that despite the regular unimpeded operation of the oppressive instruments of the National Security Law and the secret police, the anti-communist state continued to be threatened by the unremitting democratic demands of South Koreans. These demands included the exit of US forces from Korea and an economy that was responsive to the needs of ordinary people. Whenever pressure for these democratic goals exceeded a red line, the army would oust the civilian government and install a flag officer as president, all with the implicit approval of the US government, whose military commander on the peninsula had operational control of the ROK army. Washington’s interest in the suppression of the democratic demands of Koreans was obvious: it desired a continued US military presence on the peninsula to contain and possibly roll back communism, not only in Korea, but in contiguous China and Russia, as well. Korea was a valuable, geopolitically strategic perch from which the American eagle could overlook communist prey. And the Wall Street bankers and lawyers who played a central role in US policy formulation certainly didn’t want all of Korea converting to a people-centered economy. It was bad enough that the Koreans of the north had taken the socialist path.

Syngman Rhee had been brought to power by Washington in a flawed election that no one, except the US government and the few Rhee supporters, wanted. Rhee’s popular support was always limited and therefore winning a fair election was always going to be a challenge, and underhanded measures would be needed to pull off an election win. And so, in the weeks leading up to the March 1960 election, Rhee supporters routinely beat opposition supporters. On voting day, March 15, ballot boxes disappeared from areas in which the opposition was expected to win. At the same time, ballots were stuffed with fraudulent votes. All of this happened in full view of US and UN election observers, who, Bruce Cumings observed, “apparently were present to legitimate, not monitor, the validity of election.” Rhee claimed an improbable victory—almost 90 percent of the vote—sparking protests across the south. In the southwest, police killed several demonstrators. The army was called out to suppress the protests—with the approval of the army’s US commander, General Carter Magruder.47

Midway through August, Kim Il-sung made a proposal to unify the country. The proposal excited the imaginations of South Koreans, but alarmed US collaborators. Kim’s proposal, which he would table repeatedly throughout the years, was for a confederation. It would comprise one nation, one state, and one flag, but would have two sub-national governments, corresponding to the ROK and DPRK, each of which would maintain its own economic system. A national government—which would consist of representatives from both north and south, would look after foreign affairs, national defense, and intra-confederal relations. But there was a proviso that guaranteed that the US officials who dominated South Korea from behind the scenes would be hostile to the plan: Kim insisted that no foreign troops remain on Korean soil.

Students of the south were galvanized by the idea and set to work organizing a movement to link up with students of the north, in order to work for unification along the lines Kim proposed. This agitated the right wing and the security services,48 and greatly displeased US planners, for whom maintenance of South Korea as the largest power projection platform in the Pacific (in the words of the US military),49 was essential to the US imperial project.

In 1991 Kim Il-sung resurrected his proposal. Korea, he said “should be reunified by founding a confederacy based on one nation, one state, two systems and two governments. We consider that this conforms with the desire of the Korean nation to develop independently as one reunified nation and meets the requirement of the present era of independence and peace. We recognise that it is also the most feasible way of reunifying the country peacefully when different ideas and systems actually exist in the north and the south.”50 Once again, the proposal was rejected by ROK leaders. Subordinate to Washington, South Korean officials were duty-bound to reject a plan that demanded the exit of the US military from Korea. Besides, by 1991, the USSR and the Warsaw Pact had dissolved, and Communist East Germany had been absorbed into West Germany. US and ROK officials believed it was only a matter of time before the same scenario of a communist collapse followed by integration into a capitalist neighbor would play out on the Korean peninsula.

On April 19, 1960, a teeming multitude of angry students, numbering more than 100,000, descended on the presidential palace, demanding an audience with Rhee. Terrified palace guards discharged their weapons directly into the throng, precipitating mayhem on the streets of Seoul. Over 100 students were killed and nearly 1,000 were injured.51

Nearly a week later, hundreds of university professors held a peaceful demonstration demanding that Rhee step down. Matters became violent later that evening when 50,000 demonstrators attacked the home of the vice-president. The next day, a crowd of 50,000 people was back out on the streets of Seoul. With Rhee’s presidency now obviously untenable, the US ambassador and US military commander—the true power behind the puppet state of South Korea—paid a visit to the embattled president. Three days later he was gone, returning to the metropole from which he had come.52

Rhee was succeeded by the opposition Democratic Party’s Chang Myon. Chang was from a landlord family, spoke English fluently, and had been ambassador to the United States. As prime minister he consulted with the US ambassador and CIA station chief on most matters, significant and otherwise.53

Rhee’s succession by Chang Myon began what Bruce Cumings has called, “the ordeal that sent shivers up the spine of Seoul’s ruling groups”—a move to the left.54

On May 16, 1961, Park Chung-hee and a group of Army and Marine officers under his command seized control of strategic points in Seoul. The Army Chief of Staff, General Chang To-yong, appealed to his superior, the US commander, General Carter Magruder, to mobilize troops to put down the coup. Magruder refused. The next day a conspiracy of senior officers shut down the National Assembly, banned political activity, and pledged anticommunism and fealty to Washington55— precisely what the Americans who ran the show insisted on, and precisely the inverse of what Koreans, who didn’t, demanded. For the next 32 years, military leaders would occupy the presidency.

Like Rhee, Park was a vehement anti-communist. He was also a quisling, ready to sell out his compatriots to not one, but two empires. He carried with him the vile taint of Japanese collaboration, and added the vile taint of US collaboration. From 1961 until 1979, when Park’s presidency would end in his assassination at the hands of the head of the KCIA, the leaders of Korea’s two contending states were thesis and antithesis. The leader in the south had hired out his services to the Japanese to enforce their colonial rule over his compatriots. The leader in the north had led a guerrilla struggle to free his compatriots from the yoke of Japanese colonialism. The leader in the south nurtured a capital-centered economy, in which Koreans “had the right to work the longest hours in the industrial world at wages barely able to sustain one’s family.”56 The leader in the north preferred a people-centered economy and had introduced an eight-hour work day and social security within months of coming to power. The leader in the south was greatly hemmed in by the influence exercised behind the scenes by the US military commander, US ambassador and CIA station chief. Tens of thousands of US troops occupied the domain over which the southern leader’s state ruled. And his military reported, not to him, but to a US general. In the north, there were no foreign troops, and the leader preached a doctrine of self-reliance, which eschewed dependency on foreign powers. In the south, the top political leader was a traitor to the Korean project of national liberation; in the north, the top political leader was a patriot who had devoted his life to Korea’s liberation. In the south, the state was part of an empire. In the north, the state rejected empire. The state of the south was founded by a foreign hegemon. The state of the north was founded by guerrilla leaders who had fought against foreign hegemony.

To kick off his regime, Park trod a path blazed by other anti- communist dictators, as his US patrons watched and silently applauded. He dissolved the legislature and suspended the constitution. He rounded up communists and other political dissidents, tossed them into prison, and had them tortured. Among his victims were Kim Dae-jung and Kim Yong-sam, men who would later become presidents.57

Next, he oversaw the writing of a new constitution to replace the one he had expunged. The new foundational law granted him presidential powers indefinitely. He could appoint and dismiss the prime minister and cabinet at will, and suspend or abolish civil liberties by decree. He also granted himself the authority to exercise whatever additional powers he thought he might need.58 In effect, Park could have accurately declared, “L’état, c’est moi.” Except behind Park’s power lurked the far greater authority of Hirohito’s successors, the serial emperors whose abode lay in Washington. In 1973, Park prohibited all work stoppages. The year after he banned all criticism of his government.59

By 1979 Park’s capital-centered economy was sputtering. Growth had dipped below zero. The economy continued to contract, shrinking six percent in 1980.60 Growing unemployment and economic hardship touched off a wave of unrest. Massive demonstrations unsettled the country as workers and students took to the streets demanding relief from growing hardship.61

How to arrest the growing distemper? The options were repression or accommodation. On October 26, 1979, Park travelled to a KCIA safe house for discussions with Kim Chae-gyu, the KCIA supremo, on how to bring the distemper to an end. The discussion went horribly wrong, ending with Kim fatally gunning down the president.62

Park’s presidency was quickly followed by a December 12, 1979 military coup d’état, carried out by General Chun Doo Hwan, commander of the ROK army’s Ninth Division. Chun, at the time, was under the command of US General John A. Wickham, Jr., head of the US-ROK Combined Forces Command.63 A veteran of military intelligence, Chun, in power, expanded the intelligence function as a force of internal repression. The paramilitary riot police force was expanded, until it numbered around 150,000 by the mid-1980s.64 Wickham approved a role for the ROK military in politics. The army would vet political candidates. At the same time, it would supervise all political activity, preventing challenges to the state.65

In the spring of 1980, students took to the streets of Gwangju to protest Chun’s dictatorship. Wickham approved the deployment of two ROK special forces brigades to quell the disturbance and enforce martial law. On May 18, elite paratroopers landed in the city and began to indiscriminately murder demonstrators, including women and children.66 Outraged, the citizens of Gwangju fought back. Hundreds of thousands of local people drove the soldiers out of the city. It’s estimated that as many as 1,500 people died in the fighting. In the aftermath, a citizens’ council was established. Resembling the Paris Commune, the revolutionary people’s government that ruled Paris in the spring of 1871, the council governed Gwangju for the next five days.67

As the citizens of Gwangju were driving the US-commanded South Korean army out of the city, the US National Security Council was meeting at the White House to plan a response. US President Jimmy Carter, along with Zbigniew Brzezinski, his national security adviser, and Assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke, decided to approve a military intervention.68 Wickham ordered the ROK army’s Twentieth Division to deploy to Gwangju to crush the rebellion, a mission it successfully carried out a few days later. But Washington took no chances. To guarantee the success of the mission, the arrival of troops in Gwangju was delayed by three days to allow a US naval armada led by the aircraft carrier Midway to reach Korean waters, should reinforcements be required.69

Less than a year later, Chun had himself inaugurated president. Recalling the Nazi’s use of concentration camps in the early 1930s as instruments of terror against the Left, Chun established a network of concentration camps in mountain areas to terrorize the Left and bring it to heel. The police rounded up and incarcerated 37,000 known or suspected leftists, including journalists, students, teachers, labor organizers, and civil servants.70

One survivor recalled:

Right before supper we were beaten out of our minds and at supper-time we were given three spoonfulls of barley rice. Even though we offered thanksgiving for this, we were beaten again. For one laugh—80 lashings. In the morning there is a marching period which is called a screaming time but we were so hungry we couldn’t shout [so] then they beat us with clubs until we screamed. One friend of mine, a Mr. Chai, could not scream because of a throat infection and therefore, he was beaten to death. Another person, a Mr. Lee, was also beaten to death. Two out of the eleven in our group were killed.71

Military leaders would continue to fill the post of president until 1993. Over the entire span of that period, the United States had operational control of the ROK military, the institutional body from which South Korean presidents sprang. Hence, political authority in South Korea ran in a straight line from the White House to the US viceroys in Korea (the US commander of the joint US-ROK military structure, the US ambassador and the CIA station chief), and, last and least, to the Blue House, the official residence of the ROK president.

1 Cumings, Korea’s Place, 208.

2 Ibid., 350.

3 Robinson.

4 Cumings, Korea’s Place, 365.

5 Cumings, The Korean War, 46.

6 Choe Sang-hun, “An artist is rebuked for casting South Korea’s leader in an unflattering light,” The New York Times, August 30, 2014.

7 Mayer, 97.

8 Newsweek, September 23, 1974, 51-52.

9 Kinzer.

10 See: Reg Whitaker, Gregory S. Kealey, and Andrew Parnaby, Secret Service: Political Policing in Canada from the Fenians to Fortress America. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012).

11 Choe Sang-hun, “Leftist leaders accused of trying to overthrow South Korean government,” The New York Times, August 28, 2013.

12 Choe, August 28, 2013.

13 Amnesty International recommends that “South Korea abolish or substantially amend the NSL in line with the country’s international human rights obligations and commitments.” See: “The National Security Law: Curtailing freedom of expression, and association in the name of security in the Republic of Korea,” 2012. https://www.amnestyusa.org/reports/the-national-security-law-curtailing-freedom-of-expression-and-association-in-the-name-of-security-in-the-republic-of-korea/

14 Human Rights Watch says that “The law clearly violates South Korea’s international human-rights obligations” KaySeok, “South Korea: Abolish or Fix National Security Law,” Joongang Daily, September 17, 2010.

15 “National Security Law again being used in communist witch hunts,” The Hankyoreh, January 13, 2015.

16 Kraft.

17 Kraft.

18 “Man acquitted, 30 years later for ‘subversive books’ on capitalism and revolution,” The Hankyoreh, November 26, 2014.

19 Choe Sang-hun, “South Korean law casts wide net, snarling satirists in hunt for spies,” The New York Times, January 7, 2012.

20 “Military expands book blacklist,” The Hankyoreh, July 31, 2008.

21 Choe Sang-hun, “North Korean takes to Twitter and YouTube,” The New York Times, August 17, 2010.

22 Choe Sang-hun, “Korea policing the Net. Twist? It’s south Korea,” The New York Times, August 12, 2012.

23 Choe Sang-hun, “South Korean indicated over Twitter posts from North,” The New York Times, February 2, 2012.

24 Choe Sang-hun, “South Korean law casts wide net, snarling satirists in hunt for spies,” The New York Times, January 7, 2012.

25 “South Korea Police State: National Intelligence Service (NIS) Arrests Rep. Lee Seok-ki: Did ROK Lawmaker Really Try to Overthrow the Government?” Global Research News, October 1, 2013. https://www.globalresearch.ca/south-korea-police-police-national-intelligence-service-nis-arrests-rep-lee-seok-ki-did-rok-lawmaker-really-try-to-overthrow-the-government/5358043.

26 Choe Sang-hun, “Leftist leader accused of trying to overthrow South Korean government,” The New York Times, August 28, 2013.

27 Jamie Doucette and Se-Woong Koo, “Distorting Democracy: Politics by Public Security in Contemporary South Korea [UPDATE]”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, February 20, 2014.

28 Kraft.

29 Kraft.

30 Kraft.

31 Nicholas Kristof, “Free in Seoul After 44 Years, and Still Defiant,” The New York Times, August 20, 1995.

32 Kristof.

33 Kristof.

34 Kristof.

35 Kristof.

36 Kristof.

37 Kristof.

38 Kristof.

39 Kristof.

40 Polk.

41 Cumings, 2005, p. 370.

42 Cumings, 2005, p. 371.

43 Cumings, 2005, p. 372.

44 Cumings, 2005, p. 371; Matthew Burns, George E. Ogle B.D. ’54: Defying injustice in Korea,” Duke Magazine, August 1, 2003.

45 Cumings, 2005, p. 400.

46 “Pan-Africanism and Communism: An Interview with Hakim Adi,” Review of African Political Economy, http://roape.net/2017/01/26/pan-africanism-communism-interview-hakim-adi/

47 Cumings, 2005, p. 349.

48 Cumings, 2005, p. 507; Worden, 2008, p. 220.

49 Letman.

50 Kim, 1991.

51 Cumings, 2005, p. 349.

52 Cumings, 2005, p. 350.

53 Cumings, 2005, p. 351.

54 Cumings, 2005, p. 351.

55 Cumings, 2005, p. 353.

56 Cumings, 2005, p. 334.

57 Kraft.

58 Cumings, 2005, p. 363.

59 Cumings, 2005, p. 363.

60 Cumings, 2005, p. 378.

61 Cumings, 2005, p. 379.

62 Cumings, 2005, p. 379.

63 Cumings, 2005, p. 380.

64 Cumings, 2005, p. 386.

65 Cumings, 2005, p. 381.

66 Cumings, 2005, p. 382.

67 Cumings, 2005, p. 382.

68 Tim Shorrock, “The Gwangju uprising and American hypocrisy: One reporter’s quest for truth and justice in Korea,” The Nation, June 5, 2015.

69 Cumings, 2005, p. 382.

70 Cumings, 2005, p. 384.

71 Cumings, 2005, p. 384.