Writing a coherent essay in 30 minutes might seem daunting, but in this chapter, you will learn techniques of pre-construction and pre-structuring that will make the process easy. You will also learn how the essay is scored and the key factor the readers are told to look for. (Hint: It isn’t originality.)

The very first thing you will be asked to do on the GMAT is to write an essay using a word-processing program. You will have 30 minutes for your essay. You will not be given the essay topic in advance, nor will you be given a choice of topics. However, there is a complete list of most the possible writing assessment topics available for you to review on the GMAC website. Simply go to www.mba.com/us/the-gmat-exam/gmat-exam-format-timing, select the link for the Analytical Writing Assessment section, and follow the directions to download a list of current topics. Oh, and just in case you are wondering, it’s free!

The business schools themselves asked for the essay. Recent studies have indicated that success in business (and in business school) actually depends more on verbal skills than has been traditionally thought.

The business schools have also had to contend with a huge increase in the number of applicants from overseas. Admissions officers at the business schools were finding that the application essays they received from outside the United States did not always accurately reflect the abilities of the students who were supposed to have written them. To put it more bluntly, some of these applicants were paying native English speakers to write their essays for them.

The GMAT Analytical Writing Assessment (AWA) is thus at least partly a check on the writing ability of foreign applicants who now make up more than one-third of all applicants to American business schools.

At the business schools’ request, all schools to which you apply now receive, in addition to your AWA score, a copy of the actual essay you wrote.

If you are a citizen of a non-English-speaking country, you can expect the schools to look quite closely at both the score you receive on the essay you write and the essay itself. If you are a native English speaker with reasonable Verbal scores and English grades in college, then the AWA is not likely to be a crucial part of your package.

On the other hand, if your verbal skills are not adequately reflected by your grades in college, or in the other sections of the GMAT, then a strong performance on the AWA could be extremely helpful.

When you get your GMAT score back from GMAC, you will also receive a separate score for the AWA. Your essay is read by two readers, each of whom will assign your writing a grade from 0 to 6, in half-point increments (6 being the highest score possible). If the two scores are within a point of each other, they will be averaged. If there is more than a one-point spread, the essay will be read by a third reader, and scores will be adjusted to reflect the third scorer’s evaluation.

The essay readers use the “holistic” scoring method to grade essays; your writing will be judged not on small details but rather on its overall impact. The readers are supposed to ignore small errors of grammar and spelling. Considering that these readers are going to have to plow through more than 600,000 essays each year, this is probably just as well.

We’ll put this in the form of a multiple-choice question:

Your essay will be read by:

(A)captains of industry

(B)leading business school professors

(C)college TAs working part time

If you guessed (C), you’re doing just fine. Each essay will be read by part-time employees of the testing company, mostly culled from graduate school programs.

The graders get two minutes, tops. They work in eight-hour marathon sessions (nine to five, with an hour off for lunch), and are each required to read 30 essays per hour. Obviously, these poor graders do not have time for an in-depth reading of your essay. They probably aren’t going to notice how carefully you thought out your ideas or how clever your analysis was. Under pressure to meet their quota, they are simply going to be giving it a fast skim. By the time your reader gets to your essay, she will probably have already seen more than a hundred essays—and no matter how ingenious you were in coming up with original ideas, she’s already seen them.

On the face of it, you might think it would be pretty difficult to impress these jaded readers, but it turns out that there are some very specific ways to persuade them of your superior writing skills.

In a 1982 internal study, two researchers from one of the big testing companies analyzed a group of essays written by actual test takers and the grades that those essays received. The most successful essays had one thing in common. Which of the following characteristics do you think it was?

Good organization

Proper diction

Noteworthy ideas

Good vocabulary

Sentence variety

Length

Number of paragraphs

Those researchers discovered that the essays that received the highest grades from the essay graders had one single factor in common: length.

To ace the AWA, you need to take one simple step: Write as much as you possibly can. Each essay should include at least four indented paragraphs.

The test makers have created a simple word-processing program to allow students to compose their essays on the screen.

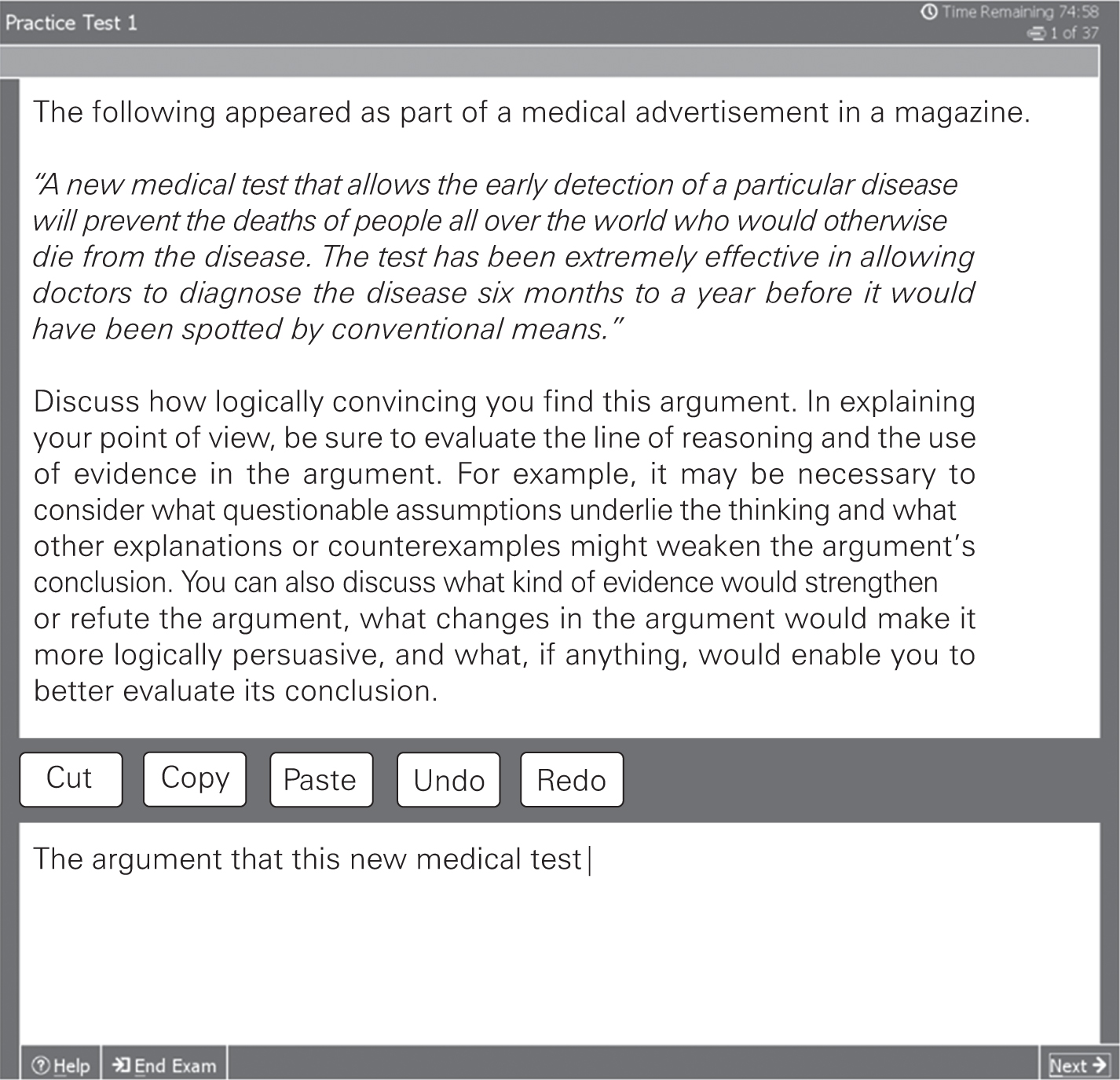

Here’s what your screen will look like during the essay portion of the test:

The question always appears at the top of your screen. Below it, in a box, will be your writing area (where you can see a partially completed sentence). When you click inside the box with your mouse, a winking cursor will appear, indicating that you can begin typing. The program supports the use of many of the normal computer keys, plus the following shortcuts:

Cut: Ctrl + X and Alt + T

Copy: Ctrl + C and Alt + C

Paste: Ctrl + V and Alt + A

Undo: Ctrl + Z and Alt + U

Redo: Ctrl + Y and Alt + R

You can also use the icons above the writing area to copy and paste words, sentences, or paragraphs and to undo and redo actions.

Obviously, this small box is not big enough to display your entire essay. However, you can see your entire essay by using the scroll bar, the up and down arrows, or the Page Up and Page Down keys.

Officially, no. Essay readers are supposed to ignore minor errors of spelling and grammar. However, the readers wouldn’t be human (so to speak) if they weren’t influenced favorably by an essay that had no obvious misspelled words or unwieldy constructions. Unfortunately, there is no spell-check function in the word-processing program.

There’s only one type of essay topic: Analysis of an Argument. The typical question will look like the text inside the screen on the previous page. Here it is again:

The following appeared as part of a medical advertisement in a magazine.

“A new medical test that allows the early detection of a particular disease will prevent the deaths of people all over the world who would otherwise die from the disease. The test has been extremely effective in allowing doctors to diagnose the disease six months to a year before it would have been spotted by conventional means.”

Discuss how logically convincing you find this argument. In explaining your point of view, be sure to evaluate the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument. For example, it may be necessary to consider what questionable assumptions underlie the thinking and what other explanations or counter-examples might weaken the argument’s conclusion. You can also discuss what kind of evidence would strengthen or refute the argument, what changes in the argument would make it more logically persuasive, and what, if anything, would enable you to better evaluate its conclusion.

You might think that there is really no way to prepare for the AWA (other than by practicing writing over a long period of time and by practicing your typing skills). After all, you won’t find out the topic of the essay they’ll ask you to write until you get there, and there is no way to plan your essay in advance.

However, it turns out there are some very specific ways to prepare for the GMAT essay. Let’s take a look.

When a builder builds a house, the first thing he does is construct a frame. The frame supports the entire house. After the frame is completed, he can nail the walls and windows to the frame. We’re going to show you how to build the frame for the perfect GMAT essay. Of course, you won’t know the exact topic of the essay until you get there (just as the builder may not know what color his client is going to paint the living room), but you will have an all-purpose frame on which to construct a great essay no matter what the topic is.

We call this frame the template.

Just as a builder can construct the windows of a house in his workshop weeks before he arrives to install them, so too can you pre-build certain elements of your essay.

We call this preconstruction.

In the rest of this chapter, we’ll show you how to prepare ahead of time to write essays on two topics you won’t see until they appear on your screen.

The Analysis of an Argument essay must initially be approached just like a logical argument in the Critical Reasoning section.

An Analysis of an Argument topic requires the following steps:

| Step 1: | Read the topic and separate out the conclusion from the premises. |

| Step 2: | Because they’re asking you to critique (i.e., weaken) the argument, concentrate on identifying its assumptions. Brainstorm as many different assumptions as you can think of. It helps to write or type these out. |

| Step 3: | Look at the premises. Do they actually help to prove the conclusion? |

| Step 4: | Choose a template that allows you to attack the assumptions and premises in an organized way. |

| Step 5: | At the end of the essay, take a moment to illustrate how these same assumptions could be used to make the argument more compelling. |

| Step 6: | Read over the essay and do some editing. |

Opinions vs. Arguments

The most common mistake our students make is offering an opinion on the topic presented in the argument. For the Analysis of an Argument essay, you need to analyze the reasoning rather than explain why you agree or disagree.

An Analysis of an Argument topic presents you with an argument. Your job is to critique the argument’s line of reasoning and the evidence supporting it and suggest ways in which the argument could be strengthened. You aren’t required to know more about the subject than would any normal person—but you must be able to spot logical weaknesses. This should start to remind you of Critical Reasoning.

The essay readers will look for four things as they skim through your Analysis of an Argument essay at the speed of light. According to GMAC, “an outstanding argument essay…

clearly identifies and insightfully analyzes important features of the argument;

develops ideas cogently, organizes them logically, and connects them smoothly with clear transitions;

effectively supports the main points of the critique; and

demonstrates superior control of language, including diction, syntactic variety, and the conventions of standard written English. There may be minor flaws.”

To put it more simply, the readers look for good organization, good analysis based on a cursory understanding of the rules of logic, and reasonable use of the English language.

In any GMAT argument, the first thing to do is to separate the conclusion from the premises.

Let’s see how this works with an actual essay topic. Check out the Analysis of an Argument topic you saw before.

The following appeared as part of a medical advertisement in a magazine.

“A new medical test that allows the early detection of a particular disease will prevent the deaths of people all over the world who would otherwise die from the disease. The test has been extremely effective in allowing doctors to diagnose the disease six months to a year before it would have been spotted by conventional means.”

Discuss how logically convincing you find this argument. In explaining your point of view, be sure to evaluate the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument. For example, it may be necessary to consider what questionable assumptions underlie the thinking and what other explanations or counterexamples might weaken the argument’s conclusion. You can also discuss what kind of evidence would strengthen or refute the argument, what changes in the argument would make it more logically persuasive, and what, if anything, would enable you to better evaluate its conclusion.

The conclusion in this argument comes in the first line:

A new medical test that allows the early detection of a particular disease will prevent the deaths of people all over the world who would otherwise die from that disease.

The premises are the evidence in support of this conclusion.

The test has been extremely effective in allowing doctors to diagnose the disease six months to a year before it would have been spotted by conventional means.

The assumptions are the unspoken premises of the argument—without which the argument would fall apart. Remember that assumptions are often causal, analogical, or statistical. What are some assumptions of this argument? Let’s brainstorm.

You can often find assumptions by looking for a gap in the reasoning:

Medical test → early detection: According to the conclusion, the medical test leads to the early detection of the disease. There doesn’t seem to be a gap here.

Early detection → nonfatal: In turn, the early detection of the disease allows patients to survive the disease. Well, hold on a minute. Is this necessarily true? Let’s brainstorm:

First of all, do we know that early detection will necessarily lead to survival? We don’t even know if this disease is curable. Early detection of an incurable disease is not going to help someone survive it.

Second, will the test be widely available and cheap enough for general use? If the test is expensive or available only in certain parts of the world, people will continue to die from the disease.

Will doctors and patients interpret the tests correctly? The test may be fine, but if doctors misinterpret the results or if patients ignore the need for treatment, then the test will not save lives.

Okay, we’ve uncovered some assumptions. Now, the essay graders also want to know what we thought of the argument’s “use of evidence.” In other words, did the premises help to prove the conclusion? Well, in fact, no, they didn’t. The premise here (the fact that the test can spot the disease six months to a year earlier than conventional tests) does not really help to prove the conclusion that the test will save lives.

We’re ready to put this into a ready-made template. In any Analysis of an Argument essay, the template structure will be pretty straightforward: You’re simply going to reiterate the argument, attack the argument in three different ways (one to a paragraph), summarize what you’ve said, and mention how the argument could be strengthened. From an organizational standpoint, this is pretty easy. Try to minimize your use of the word “I.” Your opinion is not really the point in an Analysis of an Argument essay.

Of course, you will want to develop your own template for the Analysis of an Argument essay, but to get you started, here’s one possible structure:

The argument that (restatement of the conclusion) is not entirely logically convincing, because it ignores certain crucial assumptions.

First, the argument assumes that _____________________________.

Second, the argument never addresses _____________________________.

Finally, the argument omits _____________________________.

Thus, the argument is not completely sound. The evidence in support of the conclusion _____________________________.

Ultimately, the argument might have been strengthened by _____________________________.

Here’s how the assumptions we came up with for this argument would have fit into the template:

The argument that the new medical test will prevent deaths that would have occurred in the past is not entirely logically persuasive, because it ignores certain crucial assumptions.

First, the argument assumes that early detection of the disease will lead to a reduced mortality rate. There are a number of reasons this might not be true. For example, the disease might be incurable [etc.].

Second, the argument never addresses the point that the existence of this new test, even if totally effective, is not the same as the widespread use of the test [etc.].

Finally, even supposing the ability of early detection to save lives and the widespread use of the test, the argument still depends on the doctors’ correct interpretation of the test and the patients’ willingness to undergo treatment. [etc.]

Thus, the argument is not completely sound. The evidence in support of the conclusion (further information about the test itself) does little to prove the conclusion—that the test will save lives—because it does not address the assumptions already raised. Ultimately, the argument might have been strengthened by making it plain that the disease responds to early treatment, that the test will be widely available around the world, and that doctors and patients will make proper use of the test.

Your organizational structure may vary in some ways, but it will always include the following elements:

The first paragraph should sum up the argument’s conclusion.

In the second, third, and fourth paragraphs, you should attack the argument and the supporting evidence.

In the last paragraph, you should summarize what you’ve said and state how the argument could be strengthened. Here are some alternate ways of organizing your essay.

1st paragraph: Restate the argument. 2nd paragraph: Discuss the link (or lack of one) between the conclusion and the evidence presented in support of it. 3rd paragraph: Show three holes in the reasoning of the argument. 4th paragraph: Show how each of the three holes could be plugged up by explicitly stating the missing assumptions.

1st paragraph: Restate the argument and say it has three flaws. 2nd paragraph: Point out a flaw and show how it could be plugged up by explicitly stating the missing assumption. 3rd paragraph: Point out a second flaw and show how it could be plugged up by explicitly stating the missing assumption. 4th paragraph: Point out a third flaw and show how it could be plugged up by explicitly stating the missing assumption. 5th paragraph: Summarize and conclude that because of these three flaws, the argument is weak.

You’ve separated the conclusion from the premises. You’ve brainstormed for the gaps that weaken the argument. You’ve noted how the premises support (or don’t support) the conclusion. Now it’s time to write your essay. Start typing, indenting each of the four or five paragraphs. Use all the tools you’ve learned in this chapter. Remember to keep an eye on the time.

If you have a minute at the end, read over your essay and do any editing that’s necessary.

The readers will look for evidence of your facility with standard written English. This is where preconstruction comes in. It’s amazing how a little elementary preparation can enhance an essay. We’ll look at two tricks that almost instantly improve the appearance of a person’s writing.

Structure words

Sentence variety

In our Reading Comprehension chapter, we brought up a problem that most students encounter when they get to the Reading Comprehension section: There isn’t enough time to read the passages carefully and answer all the questions. To get around this problem, we showed you some ways to spot the overall organization of a dense reading passage in order to understand the main idea and to find specific points quickly.

When you think about it, the essay readers face almost the identical problem: They have less than two minutes to read your essay and figure out if it’s any good. There’s no time to appreciate the finer points of your argument. All they want to know is whether it’s well organized and reasonably lucid—and to find out, they will look for the same structural clues you have learned to look for in the Reading Comprehension passages. Let’s mention them again:

If you have three points to make in a paragraph, it helps to point this out ahead of time:

There are three reasons why I believe that the Grand Canyon should be preserved for all eternity. First…Second…Third…

If you want to clue the reader in to the fact that you are about to support the main idea with examples or illustrations, the following words are useful:

for example

to illustrate

for instance

because

To add yet another example or argument in support of your main idea, you can use one of the following words to indicate your intention:

furthermore

in addition

similarly

just as

also

moreover

To indicate that the idea you’re about to bring up is important, special, or surprising in some way, you can use one of these words:

surely

truly

undoubtedly

clearly

certainly

indeed

as a matter of fact

in fact

most important

To signal that you’re about to reach a conclusion, you might use one of these words:

therefore

in summary

consequently

hence

in conclusion

in short

You may have noticed that much of the structure we have discussed thus far has involved contrasting viewpoints. Nothing will give your writing the appearance of depth faster than learning to use this technique. The idea is to set up your main idea by first introducing its opposite.

It is a favorite ploy of incoming presidents to blame the federal bureaucracy for the high cost of government, but I believe that bureaucratic waste is only a small part of the problem.

You may have noticed that this sentence contained a “trigger word.” In this case, the trigger word but tells us that what was expressed in the first half of the sentence is going to be contradicted in the second half. We discussed trigger words in the Reading Comprehension chapter of this book. Here they are again:

but

on the contrary

yet

despite

rather

instead

however

although

while

in spite of

nevertheless

By using these words, you can instantly give your writing the appearance of depth.

How It Works

Here’s a paragraph that consists of a main point and two supporting arguments:

I believe he is wrong. He doesn’t know the facts. He isn’t thinking clearly.

Watch how a few structure words can make this paragraph classier and clearer at the same time:

I believe he is wrong. For one thing, he doesn’t know the facts. For another, he isn’t thinking clearly.

I believe he is wrong. Obviously, he doesn’t know the facts. Moreover, he isn’t thinking clearly.

I believe he is wrong because, first, he doesn’t know the facts, and second, he isn’t thinking clearly.

Certainly, he doesn’t know the facts, and he isn’t thinking clearly either. Consequently, I believe he is wrong.

Example:

Main thought: I believe that television programs should be censored.

While many people believe in the sanctity of free speech, I believe that television programs should be censored.

Most people believe in the sanctity of free speech, but I believe that television programs should be censored.

In addition to trigger words, here are a few other words or phrases you can use to introduce the view you are eventually going to decide against:

admittedly

certainly

obviously

undoubtedly

one cannot deny that

true

granted

of course

to be sure

it could be argued that

Also, don’t forget about yin-yang words, which can be used to point directly to two contrasting ideas:

on the one hand/on the other hand

the traditional view/the new view

Trigger words can be used to signal the opposing viewpoints of entire paragraphs. Suppose you saw an essay that began:

Many people believe that youth is wasted on the young. They point out that young people never seem to enjoy, or even think about, the great gifts they have been given but will not always have: physical dexterity, good hearing, good vision. However…

What do you think is going to happen in the second paragraph? That’s right, the author is now going to disagree with the many people of the first paragraph.

Setting up one paragraph in opposition to another lets the reader know what’s going on right away. The organization of the essay is immediately evident.

Many people think good writing is a mysterious talent that you either have or don’t have, like good rhythm. In fact, good writing has a kind of rhythm to it, but there is nothing mysterious about it. Good writing is a matter of mixing up the different kinds of raw materials that you have available to you—phrases, dependent and independent clauses—to build sentences that don’t all sound the same.

The graders won’t have time to savor your essay, but they will look for variety in your writing. Here’s an example of a passage in which all the sentences sound alike:

Movies cost too much. Everyone agrees about that. Studios need to cut costs. No one is sure exactly how to do it. I have two simple solutions. They can cut costs by paying stars less. They can also cut costs by reducing overhead.

Why do all the sentences sound alike? Well, for one thing, they are all about the same length. For another thing, the sentences are all made up of independent clauses with the same exact setup: subject, verb, and sometimes object. There are no dependent clauses, almost no phrases, no structure words, and, frankly, no variety at all.

Now let’s take a look at the same passage, with some minor modifications.

Everyone agrees that movies cost too much. Clearly, studios need to cut costs, but no one is sure exactly how to do it. I have two simple solutions: They can cut costs by paying stars less and by reducing overhead.

In this version of the passage, we’ve combined some clauses and used conjunctions. This helped to add variety in both sentence structure and sentence length. We also threw in a few structure words as well. As you can see, simple techniques like these can make your writing appear stronger and more polished.

Few people are rejected by a business school based on their writing score, so don’t bother feeling intimidated. Think of it this way: The essays represent an opportunity if your Verbal score is low, or if English is your second language. For the rest of you, the essay is as good a way as any to warm up (and wake up) before the sections that count.

The GMAT AWA section consists of one essay, written in 30 minutes, using a basic word-processing program and the computer keyboard. The essay will be given scores that range from 0 to 6 in half-point increments.

Each essay will be evaluated by at least two underpaid, overworked college teaching assistants.

To score high on the AWA:

Write as many words as possible.

Use a prebuilt template to organize your thoughts.

Use structure words and vary your sentence structure and length to give the appearance of depth to your writing.

If possible, refer to a well-known work of literature or nonfiction.

For the Analysis of an Argument topic:

Step 1: Read the topic and separate out the conclusion from the premises.

Step 2: Because they ask you to critique (i.e., weaken) the argument, concentrate on identifying its assumptions. Brainstorm as many different assumptions as you can think of and write them down.

Step 3: Look at the premises. Do they actually help to prove the conclusion?

Step 4: Choose a template that allows you to attack the assumptions and premises in an organized way.

Step 5: At the end of the essay, take a moment to illustrate how these same assumptions could be used to make the argument more compelling.

Step 6: Read over the essay and edit your work.