On 15 August 1839, Charles’s first book, Journal of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of Various Countries Visited by H.M.S. Beagle Round the World under the Command of Capt. FitzRoy, R.N. was published in its own right. Previously it was published as volume 3 of Captain FitzRoy’s Narrative. The Journal of Researches is now known as The Voyage of the Beagle.

Charles and Emma’s first child, William Erasmus Darwin, was born on 27 December 1839. Emma’s unmarried and oldest sister, Sarah Elizabeth (“Bessy”) Wedgwood, arrived to help with the delivery. These were the days before chloroform became available as an anesthetic, and Charles reported that the event “knocked me up, almost as much as it did Emma herself” (Burkhardt et al. 1985–, 2: 270). Emma’s brother, Hensleigh Wedgwood, and his wife Fanny lived only four doors away and were also popping in and out at all hours to help Emma. Emma regained her strength by February 1840 (Healey 2001). In the next 17 years, Emma was to give birth nine more times!

Charles referred to his son as “a little prince” (Burkhardt et al. 1985–, 2: 250), and he wrote to Captain FitzRoy about “my little animalcule of a son.” As an infant, William was nicknamed “Hoddy Doddy” and, later, “Willy” (Freeman 1978). Ever the observant scientist, Charles immediately began making notes on William’s expressions, reflexes, and general behavior. During the first seven days after birth, he recorded William’s sneezing, hiccupping, yawning, stretching, sucking, and screaming, as well as his reaction to tickling. These observations continued into 1841 and were the subject of a scientific paper in the quarterly journal Mind (C. Darwin 1877b). Basically, Charles was gathering data on the natural history of babies. In Darwin’s groundbreaking book, The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, he discussed tear production in infants, based on his observations of William (C. Darwin 1872). This tome was one of the first books to use photography to illustrate the text (Prodger 2009).

A few passages from his paper in Mind give one a feel for Darwin’s observations of William’s behavior. “At the age of 32 days he perceived his mother’s bosom when three or four inches from it, as was shown by the protrusion of his lips and eyes becoming fixed.” “When 77 days old, he took the sucking bottle … with his right hand, whether he was held on the left or right arm of his nurse, and he would not take it in his left hand until a week later although I tried to make him do so; so that the right hand was a week in advance of the left. Yet this infant afterwards proved to be left-handed.” “When he was 2 years and 4 months old, he held pencils, pens, and other objects far less neatly and efficiently than did his sister [Anne Elizabeth] who was then only 14 months old, and who showed great inherent aptitude in handling anything.”

Darwin, the loving father, is reflected in this passage: “The first sign of moral sense was noticed at the age of nearly 13 months. I said ‘Doddy won’t give poor papa a kiss,—naughty Doddy.’ These words, without doub’t, made him feel slightly uncomfortable; and at last when I had returned to my chair, he protruded his lips as a sign that he was ready to kiss me; and he then shook his hand in an angry manner until I came and received the kiss.” When William was two years and eight months old, Darwin described his devious behavior. Apparently young William had secreted a pickle in his pinafore and was acting suspiciously. William “repeatedly commanded me to ‘go away’, and I found it [the pinafore] stained with pickle juice; so that here was carefully planned deceit. As the child was educated solely by working on his good feelings, he soon became as truthful, open, and tender, as anyone could desire.”

In March 1838 Darwin made comparative observations on a young orangutan at the London Zoo. Three-year-old Jenny was the first orangutan to be displayed at the zoo and caused a sensation with the public at large (Desmond and Moore 1991). Darwin was struck by her human, naughty emotions, much like those of a child. He compared Jenny’s reaction to a mirror with William’s more complicated response.

William suffered the indignities of both baptism and vaccination against smallpox. Charles obsessed over his own poor health and that of his children (Berra et al. 2010a, 2010b), but William was the one child that appeared robust and devoid of the hypochondria so prevalent in the rest of the Darwin household.

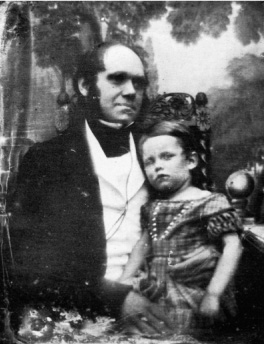

An 1842 daguerreotype of 33-year-old Charles with approximately three-year-old William seated on his lap is the only known photograph of Darwin with a family member (Desmond and Moore 1991) (Figure 3.1). As a 10-year-old boy, William had an interest in collecting butterflies (Figure 3.2). At about that age he was also given a pony, which Charles taught him to ride. William was initially educated at the Reverend Henry Wharton’s preparatory school at Mitcham and then, in February 1852, entered Rugby School in Warwickshire, the genteel, Anglican school of his Wedgwood uncles. Charles felt that the Rugby School experience closed rather than opened Willy’s mind (Healey 2001). William injured his ankle playing football at that school and wore an iron support for many years (F. Darwin 1914). Charles missed his son when the boy was away at school and ensured that Willy would spend summers at Down House with the family, including Uncle Ras (Charles’s brother, Erasmus), who was a frequent guest.

FIGURE 3.1 Charles Darwin and his first child, William, in an 1842 daguerreotype, the only known photograph of Charles with a family member. Library, University College, London.

William developed an interest in photography and received a yearly allowance of £40 to pay for supplies. This allowance was almost as much as Joseph Parslow received annually as the family’s beloved longtime butler (Freeman 1978). Darwin encouraged William to take photographs around the house and garden (Figure 3.3). An upstairs room was converted into a darkroom, where William most likely used a wet-plate collodion process to make negatives by hand (Prodger 2009). This was a very demanding technique, even for professional photographers.

FIGURE 3.2 Daguerreotype of nine-year-old William Erasmus Darwin, from January 1849, by Claudet of London. Darwin Museum, Down House.

In 1858 William entered Christ’s College at Cambridge University and eventually resided in the same room his father once occupied (Figure 3.4).

FIGURE 3.3 Left: Photograph of Charles Darwin, taken by William Erasmus Darwin, at about the time of the publication of The Origin. Charles did not grow a beard until 1862, when shaving became too irritating for his eczema. Emma was the one who proposed this solution (Burkhardt et al. 1985–, 10: 627; Colp 2008). Gray Herbarium Archives, Harvard University. Right: William Erasmus Darwin, photographed by S. J. Wiseman, Southampton. Note William’s resemblance to his father. English Heritage Photo Laboratory.

This room is now distinguished by a commemorative Wedgwood plaque and inscription (Freeman 1978). Moreover, Charles Darwin’s Cambridge lodging is alleged to be the same room previously occupied by William Paley, the theologian and author of Natural Theology, published in 1802 (Browne 1995). Paley reasoned that if you find a watch, there must be a watchmaker. This is the basis for the argument made by intelligent design creationists today. As a theology student at Cambridge, Charles Darwin read Paley’s work and wrote in his Autobiography that “Natural Theology gave me as much delight as did Euclid.” Once he discovered natural selection, however, Darwin realized that the apparent design in nature is really the undirected operation of natural forces that give the illusion of design. This was forcefully explained by Dawkins (1986) in the aptly titled The Blind Watchmaker.

FIGURE 3.4 One of Charles Darwin’s rooms at Christ’s College, Cambridge, as it looked in 1909. This photograph by J. Palmer Clark, to mark the 100th anniversary of Darwin’s birth, was published in the College Magazine for 1909. Charles’s quarters were restored to the appearance they had during Darwin’s tenure for the 2009 bicentenary of his birth. Inset: William Erasmus Darwin at age 22, who also occupied the same Cambridge room, photographed by William Farren, about 1861. Darwin Museum, Down House.

According to Van Wyhe (2009), no records exist to authenticate that Paley and Darwin were assigned the same room. He described the story as a “tradition” at Christ’s College, but added that “many such college traditions are surprisingly accurate.” One can only hope that such a symmetrical tale is true.

William was on the rowing team at Cambridge from 1859 to 1861. His crewmates regarded him with affection, and they remarked on the enthusiasm and effectiveness of his rowing (F. Darwin 1914). As he grew bald later in life, William used his long-treasured blue silk nightcap (the colors that distinguished his Christ’s College boat from others), to cover his bald spot (F. Darwin 1914).

Charles envisioned his son as a barrister and eventually as “Lord Chancellor of all England” (Desmond and Moore 1991). William studied mathematics and gave up the idea of becoming a barrister when offered a position as a partner in Grant and Maddison’s Bank in Southampton. Sidestepping the old-boy banking network was facilitated by a Darwin neighbor, John Lubbock, but Charles had to negotiate a £5,000 partners’ guarantee for a capital reserve in the event of a run on the privately owned bank. This bank eventually became Lloyds Bank.

William left Cambridge without a degree to accept the banking position, but he returned in 1862 and completed his B.A. examinations (Browne 2002). He received a B.A. degree with honors and applied for and received an M.A. in 1889 (Loy and Loy 2010). William stayed with the banking firm for 40 years, from 1862 to 1902. As a banker, he quite successfully managed the financial affairs of Charles and Emma and the extended Darwin family. In addition to the Darwin-Wedgwood wealth, Charles did very well with his books. For example, by 1861 the British and American royalties from The Origin totaled £1,219, the modern equivalent of about $100,000 (Loy and Loy 2010). William even stepped in to manage the accounts of Joseph Parslow, the family’s retired butler, when Parslow got into financial trouble. William eventually became a trustee for the inheritance of his brothers and sisters, as well as executor for his parents, uncles, and aunts (Browne 2002). When Charles’s brother Erasmus died in 1881 and his estate was settled, Charles Darwin’s personal fortune exceeded £250,000, or about $21 million in today’s terms (Loy and Loy 2010). William clearly had major responsibilities entrusted to him.

As one trained in mathematics, William reliably did the complex calculations involved in Charles’s study of purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria, during the summer of 1862 (Browne 2002). Charles had been overwhelmed by the statistical possibilities of the three-way pollination patterns of this plant. William also did some drawings and dissections for his father and read proofs. In Charles’s later years William acted on behalf of his father to prevent the use of Darwin’s name in unwanted endorsements of hot political topics (Desmond and Moore 1991).

Righteous indignation flared between Charles and William over the Eyre affair and the Jamaican Committee. Edward John Eyre was governor of Jamaica and brutally put down an insurrection of blacks in 1865. Over 400 local peasants were killed, 600 flogged, and 1,000 houses destroyed (Desmond and Moore 2009). This raised the ire of the antislavery Darwinians, including Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace, Charles Lyell, and Thomas Henry Huxley. Liberal groups formed a Jamaica Committee to advocate for the prosecution of Eyre, while clergymen, members of the military, peers, and even Charles’s dearest friend, Joseph Dalton Hooker, rallied to Eyre’s defense. When William, now 26 years old, made derogatory remarks about the Jamaica Committee at Uncle Ras’s house, Charles couldn’t contain his anger. He told William that if he really felt that way, William “had better go back to Southampton.” Charles abhorred slavery and all forms of cruelty. Early the next morning, though, Charles sat on his son’s bed and apologized for his strong outburst (Desmond and Moore 1991, 2009).

Eyre was tried three times and acquitted each time. His legal expenses were paid, and he was granted a government pension. Eyre was the first English explorer to view the huge ephemeral salt lake in South Australia in 1840. Lake Eyre was named for him in 1860.

Asa Gray (Harvard University botanist, friend, and correspondent of Darwin) and his wife visited Down House in 1868. They dined with the Darwins, the J. D. Hookers, and physicist John Tyndall. Charles had first met Gray and his wife at Kew Gardens in the spring of 1851, and he began an extensive correspondence with Gray on 25 April 1855 (Burkhardt et al. 1985–, 5: 322–323). Gray eventually became a strong supporter of Darwin’s ideas on evolution in America. A mutual friend of Gray’s and Darwin’s, Charles Eliot Norton, was staying nearby and dropped into Down House for lunches, accompanied by his wife and her 29-year-old sister, Sara Sedgwick, who caught William’s eye. This pleased Emma, who once wrote to her son advising that he choose a wife only from family friends (Browne 2002).

It was William who, after several years of suggestions, finally persuaded his father to sit for an oil portrait. Artist Walter Ouless stayed at Down House in February and finished the first oil painting of Darwin in March 1875. The Darwin family owns the original, and a copy hangs in Christ’s College, Cambridge University. Francis Darwin wrote, “Mr. Ouless’s portrait is, in my opinion, the finest representation of my father that has been produced.” Charles said, “I look a very venerable, acute, melancholy old dog; whether I really look so I do not know” (Freeman 1978). Emma didn’t like the painting, considering it rough and dismal, and she removed it from view (Browne 2002).

In Southampton in 1877, William became acquainted with Charles George Gordon of the Royal Engineers. Colonel, and later General, Gordon was known as “Chinese Gordon” for his service in the Orient during the Second Opium War and “Gordon of Khartoum” when he was governor general of the Sudan (Davenport-Hines 2004). He was speared and beheaded in the siege of Khartoum in 1885, and his body was never found. His exploits were immortalized in the 1966 Hollywood epic Khartoum, staring Charlton Heston. William, Gordon, and Gordon’s sister dined together and seemed to enjoy each other’s company enough to meet on other occasions (Loy and Loy 2010). Gordon regaled William with his adventures, war stories, and eccentric views on religion and free will.

When William and Sara Sedgwick of Cambridge, Massachusetts, the daughter of a New York lawyer and an English mother, finally got engaged, the Darwins gave them a gift of £300 (Desmond and Moore 1991). William married Sara on 29 November 1877, nine years after they first met. Sara was 38 years old and William nearly so. William and Sara’s home at Basset, Southampton, became a favorite destination for the short holidays forced by Charles’s ill health (F. Darwin 1914). William’s niece, Gwendolen (“Gwen”) Mary née Darwin Raverat, the daughter of George Howard Darwin, described the household at Basset and, by implication, Aunt Sara, as “painfully tidy, psychologically clean, rigidly perfect in organization” (Raverat 1952). William and Sara sailed to America in September 1878 to meet Sara’s family and to visit such Darwin correspondents as Asa Gray at Harvard University (Loy and Loy 2010).

FIGURE 3.5 William Erasmus Darwin and his sister Henrietta Darwin Litchfield. Darwin Museum, Down House.

William remained physically very active. As adults, William and his brother Leo bicycled the 16 miles from London to Downe (Loy and Loy 2010). A broken leg during a hunting accident, when William rashly “tried to go through a swinging gate,” resulted in the amputation of his leg, but he carried on without complaint (Healey 2001). He eventually got a wooden leg and resumed an active life, although he used a cane (Figure 3.5). He read widely on art, science, history, and biography. William was an amateur geologist and botanist and made some observations on pollination that were reported in the second edition of his father’s orchid book (C. Darwin, 1877, 99).

When Charles died at Down House on 19 April 1882, Emma and the family, as well as the village of Downe, wanted Charles to be buried in the little church cemetery, next to his brother Erasmus. Twenty members of Parliament, led by Charles’s friend and neighbor John Lubbock (who was also president of the Linnean Society) and supported by Charles’s cousin Francis Galton, Thomas Henry Huxley and Joseph Dalton Hooker, as well as William Spottiswoode (president of the Royal Society), requested that Darwin be laid to rest in Westminster Abbey, with the honor befitting the national treasure he had become. William welcomed this idea, and Emma, realizing that Charles would have wanted it also, gave her permission (Browne 2002; Loy and Loy 2010). The behind-the-scenes machinations of how this was brought about were artfully described by Moore (1982). Darwin’s closest scientific friends—Hooker, Huxley, Wallace, Lubbock, and Spottiswoode—as well as James Russell Lowell, American envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to the Court of St. James (the United States did not have ambassadors until 1893), were among the 10 pallbearers.

William was now head of the family, and he led the funeral procession, with 33 Darwins and Wedgwoods following the coffin (Healey 2001). At his father’s funeral in Westminster Abby on 26 April 1882, William, seated in the front row, felt a draught on his bald head. Fearing a cold, he positioned his black gloves on his head and remained that way until the end of the service (Desmond and Moore 1991). That must be what Gwen Raverat (1952) meant when she described William as the most unselfconscious of all her uncles!

The Times [London] (26 April 1882) described the funeral. Huxley wrote a loving obituary that appeared in Nature on 27 April 1882 (T. Huxley 1882). It contained the following elegant tribute: “One could not converse with Darwin without being reminded of Socrates. There was the same desire to find some one wiser than himself; the same belief in the sovereignty of reason; the same ready humour; the same sympathetic interest in all the ways of men. But instead of turning away from the problems of Nature as hopelessly insoluble, our modern philosopher devoted his whole life to attacking them in the spirit of Heraclitus and of Democritus, with results which are the substance of which their speculations were anticipatory shadows.”

After the death of his wife Sara in 1902, William retired from the bank and moved to London. He settled at 11 Egerton Place, next door to his brother Leonard Darwin, where he experienced a “second youth” (Raverat 1952). The Darwin family often gathered there. Gwen lived at William’s house while she was an art student at the Slade School of University College, London. She married Jacques Raverat and wrote and illustrated a delightful childhood memoir of life in the Darwin household, titled Period Piece (Raverat 1952). This book provided many revealing anecdotes about the Darwin children (Gwen’s uncles and aunts), including the charming and lovable nature of Uncle William. She wrote that “he was as nearly made of pure gold as anyone on this earth can be.” When walking arm in arm with her widowed uncle, Gwen described a scene in which a pretty girl would pass them. Uncle William “would stop dead, turn around, stare, and say loudly: ‘Good looking young woman that.’” She described him as having fresh pink cheeks, clear blue eyes, shaggy eyebrows, and white hair. Gwen remembered William’s brother Francis (Gwen’s Uncle Frank) once saying that “you could eat a mutton chop off William’s face,” because he was so clean and wholesome.

William was a strong supporter of university education for people of all classes, and he championed the foundation of a university college in Southampton in 1902. He owned an automobile, a White steam car, that he named Betsey. It was driven by a chauffeur, and William would take his nieces and nephews on excursions, sometimes even 30-mile trips. It frequently broke down and had to be pushed (Raverat 1952).

In a rare public appearance, William spoke lovingly of his father at a dinner given by Cambridge University for the Darwin Centennial in 1909. William died suddenly on 8 September 1914 in Sedbergh, where he was spending the summer with the family of his brother George (F. Darwin 1914). He was buried beside the grave of his wife at St. Nicholas’s Church, North Stoneham, near Southampton.