Spring 1851 was an extraordinarily trying time for the Darwin family. Annie died on 23 April at Malvern, leaving Charles devastated. Emma, 43 years old and deeply depressed by Annie’s loss, was eight months pregnant. She fought through the sadness, and, aided by chloroform, Horace was safely delivered on 13 May. Charles was still working on his barnacles. The house was full of curious and active children. Emma had given birth 9 times in 12 years. Surely she supposed Horace would be the last. No one can say that the Darwins did not have an active sex life!

In July 1858 the entire family, including seven-year-old Horace, enjoyed a month-long vacation on the Isle of Wight. Charles was pleased that Horace showed the usual Darwin enthusiasm for beetle collecting. A note on the beetles of Downe appeared in the Entomologist’s Weekly Intelligencer in 1859, bearing the names of Francis, Leonard, and Horace as its authors (Freeman 1982). Since they were 10, 8, and 7 years old, respectively, their father must have organized this, probably to encourage their natural-history investigations.

Just as William’s and Leonard’s interest in photography may conjure up the spirit of Thomas Wedgwood, Horace had an interest in machinery that would make his great-grandfather, Josiah Wedgwood I, proud. The innovative senior Wedgwood designed and built a pyrometer in 1782 to measure the temperature of the furnaces in which he fired his clay pottery. Perhaps this was a prescient influence behind Charles and Emma’s son becoming a world-class instrument maker. They encouraged his passion by converting the schoolroom at Down House into a workroom for Horace, complete with a lathe and other tools (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987).

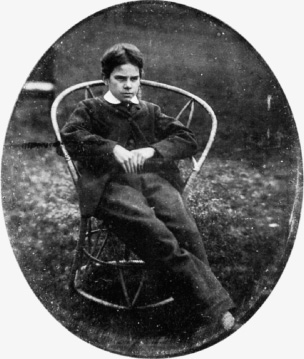

Leonard Darwin dictated a brief sketch of Horace’s life to his wife Mildred on 12 June 1932, and she transcribed it in longhand. This mini-biography was reproduced in Cattermole and Wolfe (1987) and contains an interesting look into the intellectual life of 11-year-old Horace (Figure 11.1). Charles Darwin, in a letter to Lord Avebury, wrote: “Horace said to me yesterday, ‘If everyone would kill adders they would come to sting less’. I answered, ‘Of course they would, for there would be fewer’. He replied indignantly, ‘I did not mean that; but the timid adders which run away would be saved, and in time they would never sting at all’. Natural selection of cowards!” (F. Darwin and Seward 1903, 1: 204). I can only wish that today’s students would grasp natural selection so intuitively.

By age 11, Horace developed “the shakes” and had become another ailing child for his parents to worry about. Multiple doctors at that time variously diagnosed this condition as concussion, digestive irritation, or roundworms (Loy and Loy 2010). Charles wrote to his first son, William, on 14 February 1862 (Burkhardt et al. 1985–, 10: 80): “We have been very miserable, & I keep in a state of almost constant fear, about poor dear little Skimp, who has oddest attacks, many times a day, of shuddering & gasping & hysterical sobbing, semi-convulsive movements, with much distress of feeling…. We shall have no peace in life till the poor dear sweet little man gets better.” Charles, as usual, thought this was a peculiar form of inheritance from his own poor constitution (Burkhardt et al. 1985–, 10: 92). Several doctors were consulted, to no avail.

FIGURE 11.1 Horace Darwin. Cambridge University Library.

The fits may have been a combination of the Darwin hypochondria and a plea for attention from the children’s young German governess, Camilla Ludwig, of whom Horace was extraordinarily fond (Browne 2002). The insightful Emma sent Camilla back to Germany to visit her mother and took Horace to visit William in Southampton. This seemed to break the spell of Camilla, and Horace recovered his equilibrium. Charles was appreciative of Camilla, who helped him translate German scientific papers. She eventually returned to Down House. In 1863 Horace, still a sickly child, joined his father in taking the waters at Malvern.

Horace was tutored by the local clergyman—as were his brothers George, Francis, and Leonard—and then sent to Clapham School, where he was looked after by 18-year-old Lenny, one year his senior. Like a typical Darwin, Horace had his share of illnesses and returned home for nursing from time to time. In spite of his ill health, which improved after he was 12 years old, Horace loved high jumping and riding horses, and he was considered physically strong by his brother Leonard (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987).

In July 1868 Charles was feeling unwell, and he, Emma, and 17-year-old Horace took a vacation on the Isle of Wight. The Darwins rented the home of photographer Julia Margaret Cameron at Freshwater Bay. Charles’s brother Erasmus and Joseph Dalton Hooker also made the trip to Freshwater Bay, not wanting to miss the visitations with Alfred Tennyson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow that Mrs. Cameron could arrange (Browne 2002). Longfellow was distantly and convolutedly related to the Darwins by marriage, in that he was the brother-in-law of Fanny Wedgwood’s (Hensleigh’s wife) sister-in-law, Mary Mackintosh, an American (Berra et al. 2010a, 2010b; Loy and Loy 2010). Julia Cameron managed to photograph Charles (Figure 11.2) and all the available Darwins except Emma. Charles inscribed his compliments on the right-profile picture she took of him: “I like this photograph very much better than any other which has been taken of me” (F. Darwin 1887, 3: 92; Prodger 2009).

FIGURE 11.2 Charles Darwin, at 59 years old. Photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight, in July 1868.

Another portrait taken during this session shows Darwin in left profile (see Burkhardt et al. 1985–, 16: facing 630). An engraving based on this photograph appeared in 2000 on the £10 English banknote—with Charles Darwin replacing Charles Dickens (Voss 2010). Darwin, however, considered this particular photograph to be “heavy & unclear” (Burkhardt et al. 1985–, 17: 515). Another Cameron photograph of Darwin was signed “Ch. Darwin March 7th 1874” and used as a calling card (Prodger 2009; Voss 2010).

Mrs. Cameron often used young girls as models (Voss 2010), but she felt that no woman between the ages of 18 and 70 should be photographed (Healey 2001). She also had taken a special interest in the delicate young Horace (Figure 11.3), who seemed to have an attraction for and to older women (Healey 2001). The Darwins’ visit lasted nearly six weeks.

FIGURE 11.3 Seventeen-year-old Horace Darwin, photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron, on the Isle of Wight, in 1868.

The following year, on 9 April 1869, Charles’s old horse, Tommy, stumbled, and Charles fell. Tommy fell on Charles, whose back and leg were injured by the blow (Healey 2001). Although he had previously been a daring horseman during the H.M.S. Beagle voyage and had ridden with gauchos in South America, 60-year-old Charles vowed that this was the end of his riding days. Fortunately, his injured leg recovered in a week or so. During that time he couldn’t walk, and Horace pulled him on a trolley to the greenhouse, so Charles could make observations on his ongoing botanical experiments (Browne 2002).

Horace eventually joined Francis at Trinity College in Cambridge in 1868, but Horace took six years to earn his degree, due to repeated illnesses. Upon learning that Horace had passed his set of Cambridge exams known as the “Little Go,” Charles wrote his son a letter, dated 15 December 1871. It showed Charles’s pride in his son’s accomplishment as well as a bit of Charles’s character, and the letter was reproduced in the Times [London] 1928 obituary for Horace on 24 September 1928:

My Dear Horace,

We are so rejoiced, for we have just had a card from that good George in Cambridge saying that you are all right and safe through the accursed “Little Go”. I am so glad, and now you can follow the bent of your talents and work as hard at mathematics and science as your health will permit. I have been speculating last night what makes a man a discoverer of undiscovered things; and a most perplexing problem it is. Many men who are very clever—much cleverer than the discoverers—never originate anything. As far as I can conjecture, the art consists in habitually searching for the causes and meaning of everything which occurs. This implies sharp observations, and requires as much knowledge as possible of the subject investigated. But why I write all this now I hardly know—except out of the fullness of my heart; for I do rejoice heartily that you have passed this Charybdis.

Your affectionate father,

C. Darwin.

Horace received his B.A. in mathematics in 1874 and then undertook a three-year apprenticeship with Easton and Anderson, an engineering firm in Erith, Kent (Glazebrook 2004). This aroused his interest in scientific instruments, and, while there, he built a device for measuring a plant’s response to stimulus (Glazebrook 1928). This “klinostat” was the first instrument he designed, and Francis Darwin used it for recording the rate of plant growth. Horace also learned pattern-making and foundry practices. He returned to Cambridge at the end of his apprenticeship and resided there for the rest of his life. Horace earned a living as an engineering consultant on land reclamation and drainage projects. His university contacts frequently asked him for help in designing and constructing various kinds of instruments and assorted apparatuses needed for precision measurements and the recording of events. Horace joined civil and mechanical engineering societies in 1877–1878.

Horace also invented the “worm stone” used by his father to calculate the rate at which stones on the surface were buried by the excavation activities of earthworms beneath them. This device involved a 23-kilogram (50.6 pound) flat stone, 460 millimeters (18 inches) in diameter, with a hole in the center through which a metal rod 2.63 meters (8.6 feet) long was driven into the ground (Figure 11.4). A vertical micrometer was fastened to the stone. As the stone gradually sank by the burrowing action of the worms, the micrometer measured the distance by registering it against the top of the rod (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). A substitute for the original worm stone can still be seen today at Down House. Charles Darwin began these experiments in 1877, and they were continued for 19 years, extending long after Charles’s death. The results were published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society (H. Darwin 1901). Winter readings from January 1878 to March 1886 indicated that the stone sank 17.8 millimeters in eight years, a rate of 2.22 millimeters per year. This would be the equivalent of a little less than 1 inch every 10 years. In his earthworm book, Charles Darwin had reported that small stones on the surface sank at the rate of about 2.2 inches in 10 years (C. Darwin 1881, 142), although small pieces of gravel would sink much more rapidly than the large worm stone.

FIGURE 11.4 The worm stone, designed by Horace Darwin, at Down House.

Horace and Emma Cecilia Farrer, known as “Ida,” had fallen in love, although Raverat (1952) hinted that it was Uncle Lenny who was first attracted to Ida in all her “shining Victorian perfection.” She was the daughter of Sir Thomas Henry Farrer, a rather pompous barrister and civil servant, and Frances (“Fanny”) Erskine, his first wife. His second wife was Katherine Euphemia Wedgwood, the daughter of Hensleigh (Emma’s brother) and Fanny Wedgwood (Healey 2001). Ida was Farrer’s only daughter, and he wanted to make a good marriage match for her. He thought Horace was too weak and had no career. Farrer desired a more worldly man like himself for a son-in-law—a banker or barrister. This was embarrassing for Charles and Hensleigh. The young couple could not be dissuaded, however. Charles assured Farrer that Horace would inherit enough money to live comfortably (Loy and Loy 2010), giving Horace £5,000 worth of railway stock as proof (Desmond and Moore 1991). The wedding took place on 3 January 1880 at St. Mary’s Church in London. The weather was chilly and so was the reception, as the families were not speaking to one another. The relationship between Farrer and Ida was strained for some time after her marriage (Loy and Loy 2010).

FIGURE 11.5 Left: Forty-six-year-old Horace Darwin, circa 1897. Right: Ida Darwin. Cambridge University Library.

Horace and Ida settled in Cambridge, and Charles and Emma visited them as often as possible, given their age and Charles’s health. In his earthworm book, Charles cited Farrer’s excavation of Roman ruins on Sir Thomas’s property. Gwen Raverat (1952) mentioned that as a child she felt intimidated by Aunt Ida’s perfection, compounded by the Darwins’ roughness, but as Gwen grew older she came to “love her exceedingly” (Figure 11.5).

In 1878 Horace entered into a partnership with Albert G. Dew-Smith, a wealthy friend from student days, to make instruments for scientific research. George Darwin was also involved in the development of some of the instruments used for biological research. Horace designed a series of anthropometric instruments used by his cousin Francis Galton. One of the most important devices that he designed was the rocking microtome. It allowed biologists to quickly prepare microscopic specimens for examination. In keeping with the Darwin-Wedgwood interest in photography, early in 1880 Horace invented a light meter (actinometer) that was sensitive to infrared radiation (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987).

Horace became the chief shareholder in 1880, and on 1 January 1881 the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company (CSIC), “Horace Darwin’s shop,” came into being (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). He was in sole control by 1891, when Dew-Smith retired from the instrument side of the business (Glazebrook 2004).

The partners turned their attention to the reproduction of illustrations for scientific journals. They produced gorgeous plates for Transactions of the Royal Society. In 1883 the Indonesian island of Krakatoa erupted with a violence that humans had rarely witnessed. Dust clouds circled the earth and spectacular sunsets were seen for months around the globe. The Krakatoa Committee of the Royal Society published six plates illustrating the color of the English sky seen in November 1883 (Symons 1888). These plates are considered the finest examples of the chromolithography produced by the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). Dew-Smith took over the lithographic printing business as the Cambridge Engraving Company. This lithographic business was later absorbed by Cambridge University Press. Dew-Smith died in 1903 (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987).

The Darwin family invested in the CSIC. Leonard Darwin became a director of the company, and the first share- and bond-holders included Horace, Leonard, Francis, George, William, and Elizabeth Darwin (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). Horace Darwin’s shop produced instruments for his scientific friends at Cambridge as well as apparatuses for use in schools, colleges, and industry. Horace demonstrated a real talent for design and was responsible for a striking improvement in British scientific instrumentation (Glazebrook 2004). In Horace’s obituary in Nature, R. T. Glazebrook (1928) wrote: “It was soon recognized that we had at Cambridge a firm of instrument makers the work of which would bear comparison with any in the world, while the head of the firm was a man with a genius for design and a knowledge of mechanics which enabled him to express his design in the simplest form consistent with the purpose for which the instrument was intended.”

Charles and Emma journeyed by special railway carriage to Cambridge to stay with Horace and Ida in the summer of 1881. This greatly lifted Charles’s spirits (Healey 2001). They received an early Christmas gift when their second grandchild arrived on 7 December 1881. Horace and Ida named him Erasmus, a revered Darwin name. Sadly, he was killed on 24 April 1915 during World War I at Ieper (Ypres) in western Belgium, the site of some of the fiercest fighting of the war.

Ida and Horace also provided two Darwin granddaughters, born after Charles’s death. Ruth Frances Darwin arrived on 2 August 1883, married Rees Thomas, and lived for 90 years. Emma Nora Darwin was born on 22 December 1885. She married Sir James Allen Barlow and, under the name Nora Barlow, is well known as Charles Darwin’s granddaughter. She transcribed Darwin’s 18 H.M.S. Beagle diaries (Barlow 1933). This work is an important companion to The Voyage of the Beagle. Nora edited Charles Darwin and the Voyage of the Beagle (1945), The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1809–1882, with Original Omissions Restored (1958), and Darwin and Henslow: The Growth of an Idea (1967). She may be considered the originator of the “Darwin industry” through her careful study of Charles’s manuscripts, the transcription of The Voyage of the Beagle, and the restoration of omissions made by Francis (at the behest of Emma Darwin) to Charles’s Autobiography (Healey 2001). Nora took a course on “variation and heredity” from William Bateson at Cambridge in 1906. She was a friend of Ronald A. Fisher and did hybrid experiments with flowers, including Aquilegia. A cultivar of this columbine (Aquilegia vulgaris “Nora Barlow”) is named after her (Richmond 2007; Browne 2010).

On the news of his father’s death in 1882, Horace rushed to Down House to join the other family members for the funeral. In addition to his strong family feelings, Horace was devoted to public service and was one of the founding members of the Cambridge Association for the Protection of Public Morals. In 1885, during its first year of operation, the association shut down eight brothels (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). Horace became a justice of the peace and served on various civic and university boards. He raised £5,000 for an engineering laboratory at Cambridge University, and his political maneuvering was instrumental in the creation of this modern engineering school (R. S. W. 1928; Cattermole and Wolfe 1987).

FIGURE 11.6 Horace Darwin as mayor of Cambridge, 1896–1897. Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company.

In 1895 Horace was elected to a seat on the town council, and the following year he became mayor of Cambridge, holding that office from 1896 to 1897 (Figure 11.6). His connections with Cambridge University helped unite “town and gown” by improving the relationship between the city of Cambridge and the university. Horace was interested in seismological work and was appointed a member of the Seismological Committee of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. He and George designed a type of seismograph to record very small disturbances.

When a telephone exchange was installed in Cambridge around 1885, all the Darwins living in the area became subscribers, with Horace as No. 17, George as No. 10, and Francis as No. 18 (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). Horace and George remained enthusiastic cyclists all their lives, despite numerous falls. Niece Gwen always considered Uncle Horace to be the sickliest of the Darwin brothers, with his ill heath rivaling that of her grandfather (Raverat 1952). Horace underwent successful surgery for appendicitis in 1893, when the procedure was very new and risky.

Horace was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1903, in recognition of the significance of his work in the field of scientific instrumentation. Freeman (1984) noted that the Darwins have been Fellows of the Royal Society in a father-to-son sequence longer than that of the members of any other family. The streak ran from Dr. Erasmus Darwin, elected in 1761, to George’s son, Sir Charles Galton Darwin (1887–1962), elected in 1922, a span of 201 years that encompassed five generations and seven fellows (Berra et al. 2010a). Charles was extremely proud of his sons, and in 1876 he wrote, “Oh Lord, what a set of sons I have, all doing wonders!” (Healey 2001).

World War I provided many opportunities for the CSIC. Its designers developed equipment to locate the position of enemy guns, based on measuring the time interval between the arrival of the sound of gunfire at different points on a measured base. Each unit consisted of six microphones spread out along a baseline of 9,000 yards (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). Members of the firm were also exploring anti-submarine warfare at a secret workshop known as the “Skating Rink,” where magnetic mines were developed. Horace and his company became involved in aeronautics and built wind tunnels for testing airframes. They also developed aircraft instruments, including a device to aid the pilot in maintaining a straight course in a fog. Horace helped create a height finder for determining the height and position of an object in the sky (Glazebrook 1928). He developed instruments, such as gunsights, for the new conditions of air warfare (R. S. W. 1928). He also designed and built a camera for photographing the stars. The CSIC emerged from World War I in a very prosperous condition. Horace was knighted (Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, or KBE) in 1918 as a result of his service on the Air Inventions Committee.

On 7 February 1919, Horace proposed a trademark of his own design for the company (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). It consisted of a cam (a device that converts a rotary motion to a to-and-fro motion) enclosed in an electrical bridge (Figure 11.7). The elegant simplicity of this design combined mechanical and electrical precision with a brilliant play on words. This trademark became the symbol that associated the highest standards of technical excellence with the name Cambridge. It was also indicative of Horace’s genius in simplifying complexity, the trait that made him a great designer.

FIGURE 11.7 Trademark of the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company, designed by Horace Darwin, featuring a cam and an electrical bridge, thereby symbolizing Cambridge.

The authors of a history of the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company offered a fitting tribute to Horace in the first chapter of Horace Darwin’s Shop: “Horace Darwin rarely charged realistic prices for the instruments which he designed and manufactured. His interest lay in finding the most elegant solutions to the engineering problems posed to him as an instrument designer” (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). In 1924 the firm went public, and its name was changed to the Cambridge Instrument Company.

Horace developed an interest in the training of mentally handicapped children and established a children’s home (Littleton House, in the village of Girton) with the help of his daughter Ruth (W. 1928; Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). In 1923 he endowed a student scholarship at Cambridge for the study of mental ailments, in remembrance of his son (Times [London] 1928; W. 1928).

The longtime home of Horace and Ida on Huntingdon Road in Cambridge was called the Orchard, because of its fruit trees. Horace bought this property from a larger parcel of land, the Grove, owned by his brothers William and George (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). Raverat (1952) described Aunt Ida’s house as “almost too full of detail; but beautiful, not grand—and every tiny corner of it loved and finished and exquisite.” Horace died there on 22 September 1928, at the age of 77. He had never really retired from the “shop” but placed more and more responsibility for running the business on his managers and directors. His obituary in the Times [London] (24 September 1928) is subtitled “A Great Inventor.” Burial was at St. Giles’s cemetery in Cambridge, not far from his home. Ida lived until 1946.

Even when Gwen Raverat was a child, she recognized Uncle Horace’s love of machinery. She noted that “his absorption in his dear machines always remained a barrier to me for they are not at all in my line; though I liked to watch the affection in his face and the tender movements of his beautiful sensitive hands as he touched them.”

At the end of Raverat’s (1952) reminiscences about the Darwin brothers (her uncles and father), she wrote: “When I read over what I had written about these five brothers, I felt that it might seem that I had made them too good, too nice, too single-hearted to be true. But it was true, for in a way that was what was wrong with them. I always used to feel that they needed protecting and cherishing, for they never seemed to me to have quite grown up…. They were quite unable to understand the minds of the poor, the wicked, or the religious…. But my grandfather was so tolerant of their separate individualities, so broad-minded, that there was no need for his sons to break away from him; and they lived all their lives under his shadow, with the background of the happiest possible home behind them…. At any rate, I know that I always felt older than they were. Not nearly so good, or so brave, or so kind, or so wise. Just older.”

Gwen worked for a brief time in 1941 as a factory hand at the Chesterton Road branch of the Cambridge Instrument Company as part of the war effort, before being transferred to the Admiralty as a draughtswoman (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). As late as 1958 the Darwin family still retained about 30 percent of the shares in the Cambridge Instrument Company (Cattermole and Wolfe 1987). On 14 June 1968, Horace Darwin’s shop was sold to George Kent Ltd., with the support of the government’s Industrial Reorganization Council.