3

Bank Accounts, Debit Cards, Credit Cards, and Your Credit Score

“We will never become dependent on the kindness of strangers.”

—Warren Buffett, 2009 Letter to Berkshire Hathaway Shareholders

Introduction

Okay, by now you should know who Buffett is and why you should care, as well as some of the fundamentals of how the financial markets operate. Now let's move on to the actual menu of investments and how they work. In this chapter, we'll tackle most of the things you can find at your local bank and how they affect your life. In the next chapter we'll talk about the different types of bonds and how you can estimate their value. A bond is a loan taken out by a company or government with the money provided from investors.

Insured Bank Deposits

You've probably heard the expressions “You can take that to the bank” or “You can bank on it.” It means that something is rock solid, like the Rock of Gibraltar or movie star Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson's biceps. But it wasn't always that way. Many reforms were enacted after the Great Depression of 1929–1933, the biggest economic downturn in modern history. At its worst point, more than 20% of people in the US were unemployed. During the Great Depression thousands of banks failed, resulting in many customers losing their money due to no fault of their own. In the aftermath of The Great Depression, and even today, some people keep their money “under the mattress,” which means in a safe place in their home or somewhere that is readily accessible and perceived as safe.

One of the good things that resulted from the tragedy of the Great Depression was the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Company (FDIC) and their deposit insurance program. It means that your bank account is guaranteed by the US government for up to $250,000. So if your bank goes under, your money is safe since the federal government will step in and make sure any losses are recovered to your account. For most people, there is no good reason to keep your money “under the mattress.” You're probably better served keeping it in the bank and earning some interest on it. If you keep a lot of cash home, it might get lost, stolen, damaged in a fire, flood, earthquake, or some other natural disaster. (Let's not go down the road where people are keeping money in cash from ill-gotten gains or to avoid taxes.)

To show you why it is usually exceptionally safe to keep your money in an FDIC-insured savings account, let's look at what happened during a more recent downturn, the Great Recession of 2008–2009. The epicenter of this economic calamity was with the financial services sector and especially real estate. Many banks failed and others, such as Citi, had to be bailed out or else they would have failed. How did bank account holders in FDIC-insured accounts held at perilous banks fare? Just fine, thank you. No one in an FDIC-insured account with a balance less than $250,000 lost money. It wasn't a walk in the park for all customers, since in some cases there may have been a delay or stress involved, but they got their money.

You may be thinking, “What happens if you have more than $250,000 in a bank?” Good question. Buffett would probably like the way you think! There are a few things you can do. First, the $250,000 limit is for each category. So one category can be you as an individual. If you are married, another category can be you and a spouse. There are other categories as well, including trusts, which are financial documents or structures set up by wealthy people to pass on their wealth across generations or to minimize taxes. But there is another simple solution. You can open up a second, third, fourth, and so forth, account at another bank. It gets back to the concept of diversification that we mentioned in Chapter 2. Lastly, many banks maintain insurance in excess of the $250,000 limit in case you want to keep everything in one place.

Savings Accounts and Certificates of Deposit (CD)

What do we mean when we say, “Putting your money in the bank”? To answer that question, we'll need to look at some of the different types of accounts you can open at a bank. There are a bunch of different accounts that your bank offers. Let's start with two of the most popular, savings accounts and certificates of deposit (CD). Most people over the age of 30 think about compact discs when they hear the acronym CD, but today most people listen to their music wirelessly or through an mp3 file. So if we mention CDs in this book, we're referring to the bank product and not the musical storage device. And no, there aren't any financial products that you will get confused with albums, cassettes, or 8-track tapes.

A savings account is just what it sounds like. You put your money in the bank to save, and it earns interest. The amount of interest varies on a daily basis according to market rates, but the numbers are generally low, currently around 1% per year or less. They are nearly all covered by FDIC insurance, so they’re safe. And you can get access to your money during banking hours and outside regular banking hours through an automated teller machine (ATM). Today, most savings accounts are tracked online, but in the past, it was common to get a booklet, known as a passbook savings account, that would allow you to track additions (deposits) to and subtractions (withdrawals) from the account.

If the prospect of getting 1% or less on your savings account gives you a case of the blahs, you can often get a slightly higher interest rate through a CD. The only catch is your money is “locked up” for a period of your choice, spanning from three months to 10 years. By locked up, we mean that if you want to get your money back sooner, you'll have to pay a penalty that will usually wipe out much of the interest that you've earned. So we'd suggest using a CD if you know you won't need that money until the CD matures over that three-month to 10-year period. The interest rates on a CD depend on how long you're willing to have your money locked up and the amount of money you have. Generally, larger amounts invested get you higher interest rates. Recently CDs have been giving you interest rates, also known as yields, of roughly 1%. A couple of nifty little websites that track interest rates for many financial-related items we're going to talk about are BankRate.com and NerdWallet.com. You might want to bookmark these sites and come back to them over the years, since there is no need to leave money on the table, or in your bank's pocket, rather than your own.

Savings accounts are not a great way to build wealth over the long term since they pay low interest rates and often fail to keep up with inflation, but they play an important role in the financial world. First, if you have an important expense coming up, such as a college tuition payment, car payment, or mortgage payment, or even cell phone payment, you don't want to risk it in the stock market, or other potentially volatile investment that might lose money in the short run. You should place the money for those important purchases in something safe, such as a savings account. Someday you might have unexpected things happen to you, such as the loss of a job or medical illness that affects your ability to work. The fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic literally shutdown entire industries for months at a time. Having money for important expenses or unexpected events is often called a “rainy-day fund.” Buffett has a rainy-day fund at Berkshire, but it is to the tune of $20 billion! He keeps that huge pile of cash at Berkshire because he doesn't want to be at the mercy of anyone, especially during times of distress. In Berkshire's 2009 Letter to Shareholders Buffett wrote:

We will never become dependent on the kindness of strangers. Too-big-to-fail is not a fallback position at Berkshire. Instead, we will always arrange our affairs so that any requirements for cash we may conceivably have will be dwarfed by our own liquidity. Moreover, that liquidity will be constantly refreshed by a gusher of earnings from our many and diverse businesses.

A summary of that quote merits a Tip.

Checking Accounts and Electronic Bill Payment

A checking account is another very popular type of banking product. You can view it as a savings account with a checkbook attached to it. Some checking accounts pay interest, while others don't. Most come with FDIC insurance, so you usually don't have to worry about the safety of the bank sponsoring your checking account. The main reason for having a checking account is to pay bills, which is payment for a product or service that you purchased. Of course, the good aspect of a checking account is when someone gives you a check, such as for a birthday or for a graduation present. In that case, money goes into your account. Ka-ching! Both savings and checking accounts are considered demand deposits. It's your money, and you can “demand” it, or have access to it, at virtually anytime.

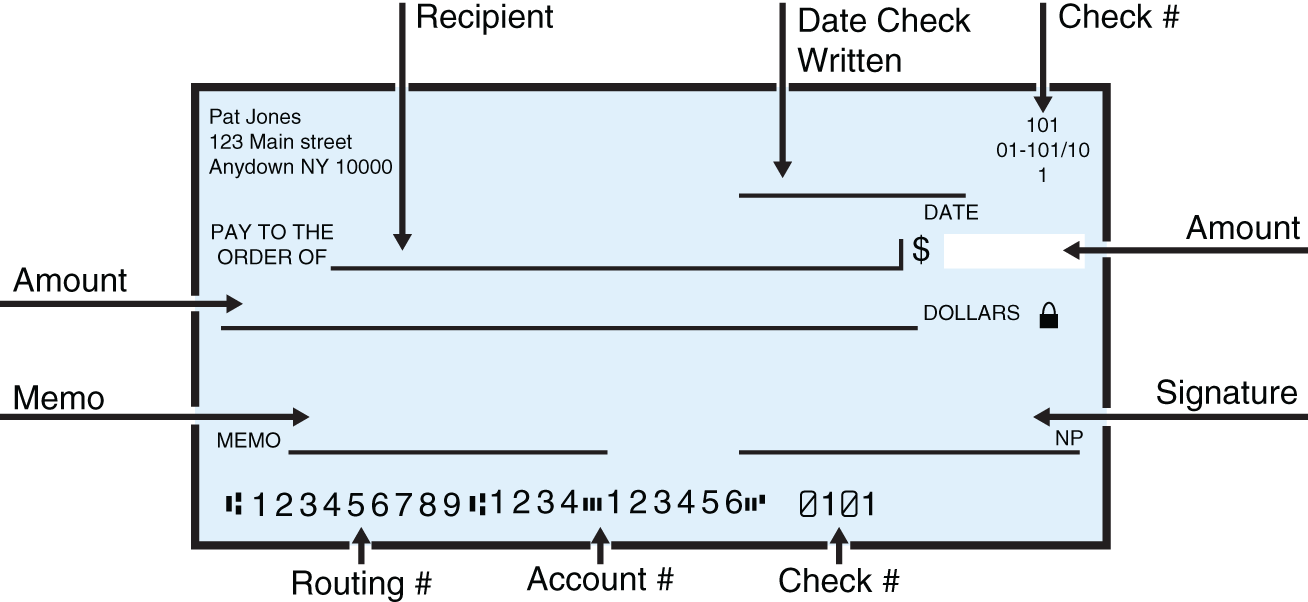

In the past, checking accounts were always pieces of paper that were part of a checkbook. A sample check is shown in Figure 3.1 below. We'll cover its different parts in a minute. Today, a lot of “checks” are written electronically. These electronic checks are usually considered to be part of the electronic bill presentment and payment system. Automated Clearing House (ACH) payments are the equivalent of electronic checks, taking money from your checking account and giving the funds to another person or organization. To make an analogy, paper checks are to regular mail as electronic checks are to email. The electronic version is faster, easier to track, and saves you a stamp. Most banks offer free electronic bill payment today.

Figure 3.1 A Sample Check

Parts of a Check

Let's go over the different parts of the check in Figure 3.1. The first part, usually in the upper left-hand corner, has your name and address. Across that to the right is the check number (each one is unique) and the date. The person who receives your check is not supposed to deposit it until the date on the check, or later. But sometimes it slips through the cracks and the check is often deposited as soon as someone receives it. So you should only send out a check when you are sure there's enough money in your checking account to cover the check. If you write a check and there isn't enough money in the checking account to pay the amount on the check, it's called a bounced check. This is something you really don't want to do. And we really mean really! The person on the receiving end of the check will be p.o.'d. They'll get hit with a fee, usually around $20 and you might also get hit with a similar fee. If you purposely bounce checks, you may have committed a crime (fraud) and can go to jail. Most banks offer overdraft protection, which will prevent checks from being accidently bounced, up to a limit, such as $500. Once the overdraft protection kicks in, you then owe that amount to the bank.

We hope we scared you about not bouncing checks, so let's get back to the different parts of the check. The next part of the check, still near the top, is the “Pay to the Order of” section. It could be anyone, but is usually paid to a person, place, or thing. Oops, that's the definition of a noun. The check is usually paid to a person, business, government, charity, or religious organization. Basically, any entity that you want to send money to.

To the right of the “Pay to the Order of” section is the amount of the check in dollars and cents, in numbers. Right below that is the same thing, the amount of the check, except written out in words. This might seem redundant to write it both in letters and numbers, but it is an important way for the computer (or in the past, person) to double-check that the amount is correct. If the two numbers don't match up then the check may be void, or cancelled.

Next, near the bottom left-hand part of the check there is a section called “For” or “Memo.” It's optional, but it acts as a reminder of what the check was used for. Examples could be anything, but “Birthday Gift,” “Cell Phone Payment,” and “School Tuition” are three common examples in personal finance.

At the bottom of the check you'll notice three strings of numbers, separated by a colon or some other strange symbol designed to signify that the three numbers are distinct. The first 9-digit number is called the American Banking Association (ABA) Routing Transit Number. This is a fancy name for identifying the bank holding your checking account funds, such as Wells Fargo, Bank of America, or Chase. Some large banks may have more than one ABA Routing Transit Number, but most have one. The second number identifies your specific checking account. It may be nice to have your bank mix up your checking account with Buffett's, but it's not going to happen. Sigh! The last number identifies the check number. It must match the number at the top that we mentioned, although sometimes you'll see an extra zero or two in front of the check number at the bottom.

If you are sending (or receiving) money internationally, there's another number you have to worry about called a SWIFT code. SWIFT is the acronym for the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication. Yeah, now you know why we call it SWIFT.

Last, but not least, at the bottom right-hand part of the check is the space for your signature. Your “John Hancock” (the fancy signer of the Declaration of Independence) that is written in cursive or script writing. When you first get a checking account, the bank asks for your signature, and the electronic system examining your check should ensure there is a reasonable match. If there is no match or no signature, the check should be rejected as being invalid.

If you notice there's something wrong with a check you have written (e.g., incorrect amount) or have second thoughts (e.g., feeling pressured to write a check to someone) you can call your bank to stop payment or cancel a check. If you sent a certified check or made a wire transfer, transactions which are guaranteed by the bank, it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to cancel them. Certified checks or wire transfers are checks where the bank verifies that the funds are in your account. They are often used in important transactions, such as a down payment for a home or for the purchase of a business. So we suggest you use “regular” checks from your checking account unless you are 100% certain you want to make a transaction.

Balancing a Checkbook

We hope we made it clear that you don't want to bounce a check. Remember, the checks could be of the paper or electronic kind. Let's work through an example of balancing your checkbook. Suppose you get $200 in birthday gift money from various friends and relatives and deposit the funds in your checking account. Assuming this is the first transaction in the account, your balance would start at $0 and then increase to $200. Next, let's say you have to pay your cell phone bill for $100. Your balance is now $100, or $200 minus $100. Then let's say you received $50 for tutoring someone (in financial literacy!). Your balance is now $150. Lastly, let's say you snag a pair of used Beats headphones from your friend for $100. Your ending balance is now $150 minus $100, or $50. The sequence of transactions, and the corresponding balances, are shown in Table 3.1.

| Checking Account Transaction | Starting Balance | Change in Balance | Ending Balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deposit $200 of birthday gift money | $0 | $200 | $200 |

| Pay $100 for cell phone bill | $200 | –$100 | $100 |

| Deposit $50 from tutoring job | $100 | $50 | $150 |

| Pay $100 for used Beats headphones | $150 | –$100 | $50 |

Balancing a checkbook is essentially addition and subtraction. Piece of cake! You can access your bank account online, so you don't even have to do the math. You can also deposit checks at most banks with an app on your smartphone that takes a picture of the check, so you don't even have to set foot in the bank branch. Most people who have problems balancing their checkbook don't follow its balance closely. Also, when you deposit cash in your checking account, you have access to the money right away. When you deposit a check in the account, it takes some time for you to get access to the funds. The length of time for you to have access to the funds is related to the clearing process. It takes most checks about 2 days to clear after depositing, but in some cases, it might take up to a week. So you should look at your account online and see what you have in available funds, which is the maximum amount you may write checks for, before writing a check.

Debit Cards and Automated Teller Machines (ATM)

Debit cards are tied to either your savings or checking account and allow you to access your money without having to carry around the physical cash. Carrying around a piece of plastic, or in some cases metal, provides some protection against having your cash being lost or stolen. Imagine if you were as rich as Buffett, carrying around billions of dollars in cash. You'd need a truck to do it! When you purchase something from a store, such as Walmart or the Apple Store, you can pay for it with your debit card. The money is deducted from your account, just like in the checking examples we discussed.

One advantage of a debit card is that you can't spend more than you have in the bank. If you try—let's say by attempting to purchase a $300,000 Ferrari with only 100 bucks in your savings account—the transaction will be cancelled. No dice! But do give us a call when you're really able to afford a Ferrari, since we'd love to take a spin. :-) Most banks will give someone a debit card as soon as age 13. Some vendors don't accept debit cards, so you'll have to pay them in cash. You can get cash by putting your debit card in an automated teller machine (ATM), also known as a “cash machine,” and withdrawing funds from your checking or savings account.

There are a few points that you should be aware of related to ATM machines. First, almost always you pay no fees when withdrawing money from at ATM machine owned by your bank (e.g., Chase, Wells Fargo, Citi, or Bank of America). However, if you have an account at Chase and try to get money from a different ATM machine, say one operated by Wells Fargo, then you'll usually get hit with a fee in the neighborhood of $1 to $3. Second, you can make deposits of cash or check into the ATM. This may come in handy when the bank is closed. As noted above, we think it's easier to deposit a check using your smartphone, but we want you to be aware of this option. Third, in order to access an ATM, you need to have a personal identification number (PIN). A PIN is set up when you open your checking or savings account and reduces the risk of theft in case someone finds or steals your debit card. The PIN is usually a 4-digit number but sometimes longer. Select a PIN that you'll remember but not something that's obvious, such as numbers related to your birthday or address.

Credit Cards and Charge Cards

A credit card looks like a debit card, but it's a lot different in how it works. It allows you to purchase things in advance of having the money leave your checking or savings account. It is basically an advance or loan from the credit card company. On paper it's good—IF you pay off your credit card bill in full each month. Why can a credit card be good? First, it is an interest-free loan if you pay your bill promptly. Second, like with a debit card, it allows you to avoid the need of holding a lot of cash. Third, with nearly all credit cards, you are not responsible for purchases if the card is lost or stolen. Fourth, most have no annual fee.

Plus, there are all sorts of reward programs, which give you things such as cash back, free airline tickets, and discounts on purchases. For example, Amazon.com has their own credit card, through Chase bank, which provides you with a 5% discount when buying things on Amazon.com. Sweet! There are a bunch of websites out there that will recommend specific credit cards for you based on your goals and spending patterns. Four popular ones are WalletHub.com, CreditCards.com, ThePointsGuy.com, and ConsumerReports.org. For some people, having a credit card can actually pay you with either cash or discounts on things that you like to buy.

So what's the problem and why do a lot of people say credit cards are bad? They can be bad for your financial future if you are not able to pay the bill off in full each month. One recent study found that 65% of Americans don't pay their bill off in full each month.

The problem with not paying your bill in full is that the credit card company charges you interest on the unpaid balance. And most cards charge a high rate of interest, to the tune of 15% or more each year. Occasionally, you'll see a credit card company offer a very low, temporary interest rate, called a teaser rate. But it will eventually revert to something much higher.

At the 2020 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting, which was held virtually due to COVID-19, Buffett relayed an insightful story about the importance of paying credit cards in full each month. A friend approached him looking for investment advice. She was hoping for a stock tip, but she was disappointed when Buffett told her the first thing she should do is pay off any credit card balances. The interest rate she was paying on her credit card was a not uncommon 18%. Buffett told her he didn't know of any investment that would pay her 18% per year, looking ahead. He then dispensed some tip-worthy advice saying, “Avoid using credit cards as a piggy bank to be raided.”

Remember, Berkshire's stock has historically increased 20% per year, and Buffett is likely the greatest investor ever. It's extremely unlikely that what you purchased with the credit card will go up in value more than the interest rate the bank charges. Most people use their credit cards to buy goods or services that they consume, such as clothes, food, vacations, electronics, and the like, that don't increase in value over time. In fact, they usually decrease in value quite rapidly, if not disappear, such as a Starbucks latte or a snack of avocado toast. The bottom line is that credit card debt that is rolled over from month to month will be destructive to the wealth of nearly everyone that has it. To explain this rollover concept, we have to go into some of the details on how a credit card works.

First, you have to apply to get a credit card, usually from a bank. For most people, you need to be at least 16 years old, often with a parent or guardian personally guaranteeing payments. If you're 18 years or older you can apply for a card without permission from someone else. Frankly, for most people, it's not hard to get approved for a credit card, even if you have no credit history. Let's say you're approved. They bank will mail you a credit card, and you'll have to activate it by calling a toll free number or by going to their website. The credit card will come with a limit, unless you're super rich. Like Kylie Jenner or Jay-Z rich. For people with little to no credit card history, the limit is usually in the $500 to $2,000 range.

Continuing with our example, you can go crazy and buy $2,000 worth of stuff, even if you have only 5 bucks in your checking account. Obviously, we don't recommend it, but some people are swayed by their peers to buy things or simply aren't responsible with their money. The trouble starts when you get the bill, usually within 30 to 45 days of your first purchase. The credit card company will send you a bill that says what your required minimum payment is, as well as the payment if you want to pay the bill in full ($2,000 in our example). The required minimum payment varies by credit card company but is typically 3% to 5% of what you owe the credit card company, sometimes referred to as the balance or amount outstanding. In our example, if you pay 3% of $2,000, or $60, the remaining amount, $1,940, would incur interest costs.

As long as you pay the required minimum payment each month, your credit card is kept “on.” This is the “rollover” strategy we alluded to earlier. You are basically kicking the (debt) can down the road. But paying the minimum isn't a winning strategy since your debt can really snowball out of control. Using some round numbers, if you have $2,000 in debt and compound that for 10 years at an interest rate of 20%, you'd owe $ 12,383. Ouch! That's a tough hole to dig out of, so the best way to avoid it is to pay the balance in full each month. If you don't have the discipline to do it, then you should just stick with the debit card.

Buffett's character in Secret Millionaires Club weighed in on the topic of just paying the minimum on your credit card in colorful fashion. He said, “Making those minimum payments while you continue to charge is like bailing out a sinking ship with a teaspoon. Pretty soon, you are in way over your head.”

Before we move on, there is also something similar to a credit card, called a charge card. The charge card requires you to pay your balance in full each month. If you don't pay in full, then the card may be turned “off,” and you'll incur (usually high) interest rate charges. American Express became famous in part for issuing charge cards but now offers a range of credit cards too.

Apps to Send Money: PayPal, Venmo, Zelle, Apple Pay, Android Pay, and so forth

Sending money to pay for things or giving money to people, such as friends and family, is a pretty common occurrence. Let's say you're buying something, such as a used game of Monopoly, from another person on eBay, the most popular auction website. You can send the person selling you the Monopoly game a check in the mail, but it will take awhile for them to get their check and for the check to clear. The seller also may not be in a position to accept credit cards. To accept a credit card, you need to be approved by one of the credit card companies, such as Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover.

Not surprisingly, some products were developed to fill these gaps. One of the first solutions is PayPal. And also not surprisingly, PayPal was once owned by eBay but now exists as a separate company. PayPal allows you to pay for something or send money by taking the money from your checking account or by making a charge to your debit or credit card. PayPal isn't a charity, it does this for a small fee. The fee, typically 2.9% of the transaction price plus 30 cents, is taken from the seller of the good—the Monopoly game in our example. The buyer typically pays no transaction fees.

As smartphones developed, techniques were used to send or receive money through apps on your phone. The most popular one currently is Venmo. PayPal owns that too. You may view Venmo as a digital wallet that allows people to send money directly to each other. One thing that's cool about Venmo is you can send a person money just by having their phone number or email address, assuming they also have a Venmo account. There's also a window of time, usually from a day to a week, where you can cancel the transaction if you suffered from a bout of temporary insanity.

The Venmo app works behind the scenes to send the money to the person's bank account without having you know their information. If you use a credit card to send money, Venmo charges a 3% fee. For most other transactions, it's free. Venmo also has a social media component, somewhat like Facebook. It has news feeds, comments, and other feature3 as well, such as the part of its app that helps you quickly split a bill. Venmo has caught on like wildfire and has more than 40 million active users. Not surprisingly, other firms wanted a piece of the action and came out with similar apps. Google/Alphabet offers Android Pay. Apple offers Apple Pay. A group of large banks combined resources to form Zelle, which is now running neck and neck with Venmo.

Let us tell you about one more resource for sending money. There has been a company doing it for more than 150 years. Western Union was founded in 1851 and is famous for their slogan, “The fastest way to send money.” That slogan doesn't resonate as much today with apps such as Venmo, but Western Union has over 500,000 locations in more than 200 countries around the world. They have various businesses that facilitate the transfer and receipt of money, including cold hard cash.

Although it's very easy to send money to people, including friends and family, it doesn't mean you should do it without careful thought. During one episode of Secret Millionaire's Club, Buffett's character said, “You have to think carefully before you loan money to anyone, especially a friend.” The reason is that if they don't pay you back, either willfully or due to difficult circumstances they are facing, it may create problems in your relationship. In some cases, it might end the relationship. And if you're dealing with relatively small amounts of money, that's probably not a good trade-off (i.e., loss of a friend over a loss of a relatively small amount of money). So we and Buffett aren't saying you should never do it but just that you should think long and hard about it.

Your Credit Score: A Report Card of Your Financial Responsibility

You might be done with receiving a report card when you finish college. Sorry to break it to you, but there's something similar to a financial report card that you'll have for the rest of your life, called a credit score. A credit score measures how responsible you are when borrowing money. Borrowing money could take many forms, including credit cards, student loans, car loans, home mortgages, and even utility bills. You should check your credit report at least once a year. It may contain some errors that you will want to get corrected. Buffett once checked his credit score and found it to be 718, modestly above average, even though he is one of the richest people in the world! He found he had an imposter who opened a credit card in his name and didn't pay the bills. He eventually got things fixed, and presumably his credit score is near the top of the upper range. If having an error on a credit report can happen to Buffett, it can happen to anyone, so let's create a new Tip.

Your credit score is a number that ranges from 300 (worst) to 850 (best). The average credit score in America is about 700, although it changes a bit every year. There are a few firms that compute credit scores. The most popular credit score is called a FICO score, named after the financial firm that created it, Fair, Isaac, and Company. Credit scores differ somewhat by age. Younger people tend not to have much of a credit history and so usually wind up with lower credit scores. Why is a credit score such a big deal? Well, if you have a high credit score, you often will pay a lower interest rate when you borrow money for “big ticket” purchases, such as a car or home. And that will save you a lot of money, especially with a mortgage that might last 30 years. So you want to get the best credit score that you can, just like you wanted to get an A on important exams.

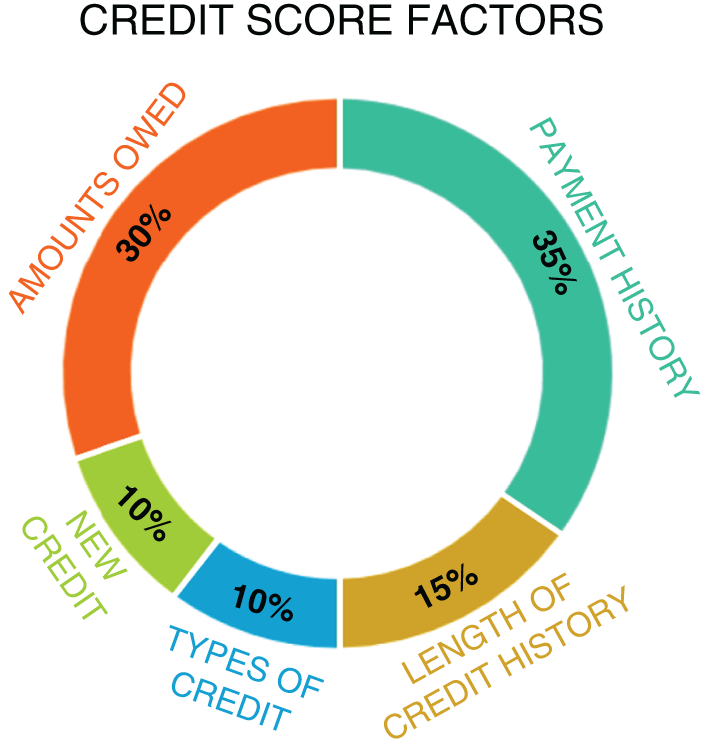

How is a credit score calculated? The exact formula is somewhat of a secret, but Fair Isaac has given out some information that suggests your FICO score has five categories, as shown in Figure 3.2. Your payment history counts for about 35% of the score. The amount of money that you owe counts for another 30%. The length of your credit history accounts for 15%. The number of new credit applications accounts for 10%, and the type of credit used (e.g., credit card or student loan) counts for another 10%. Young people are less likely to have a long credit history and have more new credit applications than someone that is over 30. However, you can pay your bills in full on time every month, which would give a nice boost to the two biggest weights that go into computing your credit score.

Figure 3.2 Components of a Credit Score

Borrowers with the strongest credit scores—generally 740 and above—are put in the prime category. They nearly always pay their bills on time and don't carry much debt. They also typically have a long credit history of a decade or more. Occasionally, you'll read about a super-prime category. These individuals typically have credit scores of at least 800 and may pay even lower rates than prime borrowers.

The second of the four major credit categories is called Alt-A. Alt-A means that you have a good credit score but perhaps are not strong in one or two categories, such as length of credit history. Many younger borrowers fall into this category. The typical FICO range for the Alt-A category is 670 to 739. The third-lowest credit rating category is called subprime. Borrowers with a subprime credit score typically score poorly on many of the credit factors, such as not paying their bills on time or having too much debt relative to their income. The lowest credit category is simply called poor. These borrowers don't have a good record of paying their bills on time, or at all. In some cases, they have declared bankruptcy.

Personal Bankruptcy: Try to Avoid at all Costs

Bankruptcy refers to a legal process that is pursued when you have significantly more debts than assets and you want to try to get some of your debts reduced or eliminated. Individuals, companies, and some governments may declare bankruptcy. Individuals may declare bankruptcy for many reasons but among the most common are medical debt, loss of a job, losing a lawsuit, business losses, and purchasing items (e.g., home, car, or jewelry) that they couldn't afford. Buffett's own sister, Doris, had a brush with bankruptcy in the 1980s due to some bad and risky investments, so it's not just a problem for those with lower income.

On the surface, you might think having some of your debt erased sounds good. But bankruptcy can be very bad since your credit will be tarnished for a very long time, typically seven years or more. Declaring bankruptcy might make it very difficult to get a mortgage or other loan in the future. And if you do, you will likely pay a much higher interest rate than someone with a good credit rating. Declaring bankruptcy kills your credit score, putting you firmly in the poor or subprime categories.

A bankruptcy court may eliminate some, or all, of your credit card debt, but it won't get rid of student loan debt and some other types of debt. Up until the mid-1800s in the US, bankrupt persons were often placed in a debtors' prison where they were required to work to pay off their debts. Today, those who declare bankruptcy are put in the equivalent of a “financial penalty box” but not prison. However, some state laws do provide for the equivalent of prison sentences for individuals unable to pay debts. In some cases, you can negotiate with your lenders and voluntarily have them take less than what they are owed. This negotiated reduction in debt might hit your credit score but not nearly as much as a formal declaration of bankruptcy. The best way to avoid bankruptcy is to purchase only things you can afford and to have the discipline to invest on a regular basis. In short, try to avoid bankruptcy at all costs.

A Word on Bitcoin from Buffett

This might surprise you, but it used to be possible to exchange currency (e.g., a $20 bill) in the US for gold coins or bars, known as bullion. And the reverse trade worked too, swapping gold for paper money. The ability for individuals to make this trade ended to a great extent in 1934 when the Gold Reserve Act was enacted. The point of this discussion is that there used to be an explicit link between gold and money, which, in aggregate, is known as the money supply. There are different definitions of what constitutes the money supply, but the most conservative definition (known as M1) consists of physical currency/bills, coins, demand deposits, and traveler's checks. Basically, M1 consists of cash or something that may be converted to cash very quickly.

In theory, if enough gold wasn't held at Fort Knox, or some other federal depository, the printing or coin press couldn't be run. That all changed in 1971 when the US went off the gold standard, meaning that currency could no longer be exchanged for gold, even for the institutions that were previously permitted to do so after the enactment of the Gold Reserve Act. Nearly all countries around the world followed suit, ending their gold standards. The reasons for going off the gold standard are beyond the scope of our book, but many government leaders felt that being tied to a gold standard restricted the ability of the economy to grow.

Today, most money printed is called “fiat.” No, not the Italian car, but the currency is declared to have value by government decree. So in theory, the government could crank the printing press at full steam and not worry about anything. Also in theory, the more money printed, the more inflation that would occur. We'll cover inflation in more detail in Chapter 4. If money was printed like it was going out of style, it should push the prices of most things up, resulting in inflation.

So what does all this have to do with Bitcoin? Well, the (still unknown) creator(s) of Bitcoin wanted to create a currency that couldn't be arbitrarily devalued by running the printing press. The creator of Bitcoin also wanted a way of transmitting (i.e., sending and receiving) money that was anonymous, beyond government control, and could be used for all types of business and personal transactions. Even for black market, or illegal transactions beyond government oversight or taxation. For example, writers of ransomware, software that “hijacks” someone's computer, often demand to be paid in Bitcoin.

The details of how Bitcoin works is also well beyond the scope of this book, but you can think of it as an alternative digital currency, known in some circles as cryptocurrency. Today, you can even see a Bitcoin machine in some locations, which looks a lot like an ATM machine. It might sound like science fiction, but Bitcoin is accepted as money by many firms today, including Dell, Microsoft, PayPal, and the Wikimedia Foundation, operator of the famous Wikipedia website. They think of Bitcoins in the same way as you might think of a US dollar, euro, British pound, Japanese yen, or Chinese renminbi. Basically, as money.

The price of Bitcoin has skyrocketed, going from less than a penny a “coin,” shortly after its creation in 2008–2009, to almost $20,000 in 2018 and now roughly $11,000 as we are writing this book. That's a peak return of about 100 million percent! A feat that even Buffett can't match! While on the topic of astronomical returns, we'll tell you a Wall Street expression about the difficulty of having perfect timing. “The only person that buys at the bottom and sells at the top is a liar.” So what does the Oracle of Omaha have to say about Bitcoin? It's a controversial topic, so we'll include Buffett's full quote and then make some comments afterward. Buffett said:

Stay away. Bitcoin is a mirage. It's a method of transmitting money. It's a very effective way of transmitting money and you can do it anonymously and all that. A check is a way of transmitting money, too. Are checks worth a whole lot of money just because they can transmit money? Are money orders? You can transmit money by money orders. People do it. I hope Bitcoin becomes a better way of doing it, but you can replicate it a bunch of different ways and it will be. The idea that it has some huge intrinsic value is just a joke in my view.

Buffett's feelings on Bitcoin are pretty clear, so we're going to put that as a Tip. There are a couple of words in Buffett's response that may require an explanation. We'll define “intrinsic value” in more detail in Chapter 6, but for now, you can think of it as a reasoned measure of what something is worth. For example, the intrinsic value of a house includes the land, materials, and benefits of living in a certain community, such as its school system or proximity to work. Money orders are a way of sending money, other than physical cash, if you don't have a checking account. It's rarely a good idea to send cold, hard cash in the mail. You can get a money order from the post office or most banks (as two examples), swapping cash for the money order, for a fee. The fee is usually less than 1 percent of the size of the transaction (e.g., the fee is less than $5 for a $500 money order), although the fee may be a bit higher on a percentage basis for small transactions.

Our job here is to educate and not pontificate. At this point, we can objectively say that Bitcoin as an investment is speculative or risky. Its volatility has been incredible, often moving hundreds of dollars in price in a single day. There have been people who have had their Bitcoins stolen by cyberattacks. But the notion of an anonymous currency that is not based on fiat and not tied to a specific government has some appeal and we expect the cryptocurrency industry to continue to evolve. We talked about Buffett's belief of staying within your “circle of competence.” Cryptocurrencies are not within our circle of competence, so we will be like most observers today and just wait and see what happens with Bitcoin.

References

- Akin, Jim. “What Are the Different Credit Score Ranges?” Experian, January 7, 2019. http://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/infographic-what-are-the-different-scoring-ranges/.

- Buffett, Warren. “Letter to Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.” Berkshire Hathaway, Inc., 2009. https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2009.html.

- Buffett, Warren. Secret Millionaires Club: Volume 1. A Squared, 2013. https://www.smckids.com/.

- “Great Depression.” History.com. A&E Television Networks. Accessed June 27, 2020. https://www.history.com/topics/great-depression.

- Hill, Kashmir. “Bitcoin Battle: Warren Buffett vs. Marc Andreessen,” March 27, 2014. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kashmirhill/2014/03/26/warren-buffett-says-bitcoin-is-a-mirage-why-marc-andreessen-thinks-hes-wrong/.

- Langager, Chad. “How Is My Credit Score Calculated?” Investopedia, February 12, 2020. http://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/05/creditscorecalculation.asp.

- Loomis, Carol. Tap Dancing to Work: Warren Buffett on Practically Everything, 1966–2012. London: Portfolio Penguin, 2014.

- Steverman, Ben. “The Credit Card Rewards War Rages. Are You the Loser?” Bloomberg, June 26, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-06-26/the-credit-card-rewards-war-rages-are-you-the-loser.

- “Warren Buffett: People Should Avoid Using Credit Cards as a Piggy Bank to Be Raided.” Yahoo! News. Yahoo!, May 3, 2020. https://www.yahoo.com/news/warren-buffett-people-avoid-using-011209713.html?bcmt=1.

- Wolff-Mann, Ethan. “The Average American Is in Credit Card Debt, No Matter the Economy.” Money, February 9, 2016. https://money.com/average-american-credit-card-debt/.