Into the Mad, Metaphysical Realm

I went into the bedroom to check the time on the watch I had left by the bed. But the watch had stopped.

—Murakami Haruki, Umibe no Kafka

Supernatural or metaphysical elements have been an integral part of Murakami Haruki’s fiction from the beginning of his career. In those early days, however, those elements, which are widely understood to be associated with that type of writing known as magical realist, presented themselves as peripheral to the principal narratives being told. They were, rather, a means or a tool by which the Murakami hero gained access to his inner mind, the metaphysical realm. It is even possible that the author himself, as he learned through practice the craft of writing in these early works, was not wholly aware of the centrality of that “other world” to his narratives. As a tool that world was functional, to be sure, but we see little urge in Murakami’s first few works to explore it in any great detail.

Near the end of Hear the Wind Sing, for instance, when a boy throws himself into a seemingly bottomless well on Mars, emerging more than a billion years later to have a chat with the wind, the well and its adjacent tunnels receive no more than a few lines. When the boy realizes he is really talking to himself, he ends his life. In Pinball, 1973 the “other world” is presented as a cavernous cold-storage facility filled with pinball machines, but still, in the end it is just a warehouse. Readers may even have missed the growing sense of unreality that unnerves the protagonist as he makes his journey to the warehouse by taxi, a point I make in greater detail below.

This idea of the journey to the “other world” as a process of moving from “this side” to “over there” gains ground and detail in A Wild Sheep Chase when the protagonist moves from Tokyo to Hokkaido and gradually to more and more remote places, until he finally penetrates the core of the metaphysical realm in the form of his friend Rat’s mountain villa. Not until Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World does Murakami attempt a detailed and focused examination of the “other world,” yet even in this instance he shies away from description of the actual inner mind; rather, “the Town,” as we saw in the previous chapter, is an artificially constructed approximation of the inner world. Nonetheless, this novel gives our first hint of the growing importance of the inner world in Murakami’s mind.

Perhaps this is why, even in works like Norwegian Wood and South of the Border, West of the Sun—by the author’s own estimation written in a quasi-realist mode—the “other world” continues to make its presence known. Norwegian Wood concerns the relationship between a college student named Watanabe Tōru and Naoko, a young woman suffering from a serious psychological condition that, in all likelihood, resulted from the suicide of her boyfriend Kizuki some years previously. Watanabe, who loves Naoko himself, tries desperately to keep her in this world, on “this side,” but to no avail; for Naoko, the voices she hears calling her from “over there”—the land of the dead—are too attractive to ignore. South of the Border, West of the Sun is the tale of a middle-aged husband and father named Hajime, who suddenly runs across a woman he knew in childhood. He makes up his mind to run away with her, but in the end she disappears—again, very likely into the “other world”—before he gets the chance. In both of these so-called realist narratives the metaphysical realm always lurks just beside these characters, calling to them, inviting them to cross over to the other side. It is a motif that returns with great prominence in the most recent work, Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, as well.

We see the trend away from the individual model of the “this side-over there” dichotomy toward a more collective one beginning with The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, a signal that Murakami was beginning to recognize more clearly that the metaphysical realm is more than simply a means of reconnecting with the individual past; rather, from this point it begins to take shape as a venue in its own right, the very point of creation and continuation of what might be called the human experience. Marked by its transcendence of the human construct of time, preserving simultaneously all human consciousness and memory, past and future, the metaphysical realm now grows into a timeless Time and a spaceless Space wherein characters are connected yet at the same time absorbed, dissolved into the totality and wholeness of the realm, merging with all humanity, living, dead, and yet to be born.

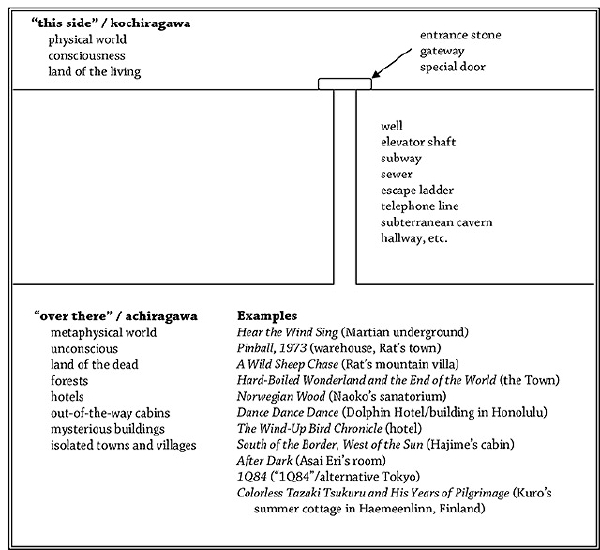

Mapping “Over There”

Before getting into a detailed consideration of how the “other world” functions in Murakami fiction, we need to examine some of the important characteristics of this realm. There is, of course, no one simple way of describing the “other world,” given the guises it takes across the broad spectrum of the author’s repertoire, a fact that has contributed, no doubt, to the variety of labels that have been applied to it. I have generally preferred terms such as metaphysical realm and other world, but many Japanese critics opt for the even less specific achiragawa, or “over there.” Part of our challenge lies in the fact that this achiragawa is many things at once: a metaphysical zone, freed from the constraints of time and space; a wormhole, or conduit into other physical worlds; an unconscious shared space, similar to Jung’s collective unconscious; a repository for memories, dreams, and visions; the land of the dead; the “world soul” of mysticism; heaven or hell; eternity. With respect to Murakami’s fictional landscape, it is most effective to imagine this realm alternately as psychological or spiritual, though at times these clearly overlap. This is because the characteristics that mark the unconscious as envisioned by psychoanalysis, for instance, are frequently similar or identical to those that mark traditional visions of the underworld, of the mystical “world soul,” and the spirit world. As we shall see, most of Murakami’s stories shift back and forth between these two conceptualizations of “over there.”

Murakami’s metaphysical other world stands outside the boundaries of what we think of as reality, can (usually) be reached only unconsciously, by accident or chance (much, in fact, like entering the state of sleep); it contains no actual fixed boundaries (though this is not always evident to visitors); it is seldom found the same way twice; and when “time” exists there at all, it seems to run unpredictably, in all directions, quite unlike the linear, mono-directional tool we have constructed in the conscious, physical world. The reason for this, ironically, is most simply and clearly stated by the celebrated theoretical physicist and mathematician Stephen Hawking, who writes in A Brief History of Time that “[t]he increase of disorder or entropy with time is one example of what is called an arrow of time, something that distinguishes the past from the future, giving a direction to time.”1 This, however, cannot occur in the metaphysical world, because, transcending the physical as its name implies, neither entropy, nor indeed change of any kind, can affect what is stored there. Psychologist Iwamiya Keiko, writing on Kafka on the Shore, notes similarly that “on the other side of the ‘gateway stone,’ the everyday flow of time is transcended, we are separated from the world grounded in cause and effect, and another, different sort of reality comes into being.”2 This is paralleled in our conceptions of the psyche, for, as Freud notes in his introductory lectures on psychoanalysis, “[i]n the id there is nothing corresponding to the idea of time, no recognition of the passage of time, and . . . no alteration of mental processes by the passage of time.”3

The key phrase in Freud’s statement is the “passage of time,” for time does not “pass”—does not move—in the other world. It would be a mistake to imagine, however, that no form of time exists there; rather, that realm is bound up in a transcendent form of what I will call “Time” (with a capital T), something like Plato’s ideal. This Time exists in the “other world” as a totality, a unity that precludes any distinction between past and future, functioning solely as an endless “present.” This is why we often have the illusion of timelessness in the metaphysical realm, and why those who enter it can never gain their temporal bearings, for the meaning in any specific time in the physical world is grounded in its distinction from all other times that it is not. Because Time exists as a solitary unity in the “other world,” these distinctions, by definition, cannot exist.

Freud’s dictum on time is useful here, for we may understand the metaphysical realm in early Murakami fiction to correspond, roughly, at least, to Freud’s concept of the “id,” the reasons for which are not necessarily capricious. Beyond the happy pun on the terminology—the Japanese pronunciation of “id” is ido, a homonym in Japanese for “well”4—the well turns out to be an ideal sort of image for Murakami’s purposes, as it both physically and figuratively leads from the world “up here”—that is, the world of light and life, of the everyday—down through a mysterious, often perilous shaft into the underworld, where darkness, cold, and, of course, death lie in wait. Over time Murakami has expanded his repertoire of such passageways to include elevator shafts, telephone lines, hallways, subway tunnels, ladders, sewers, and subterranean caves, among other things. Sometimes the conduits are blocked off, as indeed the metaphysical world is sometimes blocked off as well, while other times it stands open.

Physical and metaphysical realms

Suspension of physical time and space are not the only aspects of Murakami’s model of the metaphysical world that stand out or remain constant in the author’s work today. He commonly characterizes the place as dark, dank, and cold (though this has changed slightly in degree in recent years) with a persistent sense of dread or foreboding. In later works—most notably from The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle in the mid-1990s—the area has become a labyrinth, but even this was hinted at a decade earlier in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World when Murakami added a surrounding forest to the unconscious Town in which his protagonist was trapped; the forest is an obvious image for the maze or labyrinth because the trees all tend to look the same, and one easily becomes lost. The forest, as Joseph Campbell notes, is also a common setting not only for magical unions that occur between lovers in ancient legends (Tristan and Isolde, Lancelot and Guinevere) but for the mystical trials that befall mythological heroes, the destination for “the questing individual who, alone, would seek beyond the tumult of the state, in the silences of earth and sea and the silence of his heart, the Word beyond words of the mystery of nature and his own potentiality as man—like the knight errant riding forth into the forest ‘there where he saw it to be the thickest.’”5 Campbell’s understanding of the forest as a departure from the impositions of the State is both appropriate and yet ironic in the context of Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, whose hero is essentially banished to the “forest” by the State itself, yet finds in the metaphysical forest a place that appears to lie beyond the reach of the forces that seek to control him.

Yet another aspect of the metaphysical realm is its surrealist atmosphere, accompanied by the gradual loss of memory and will. This, too, is prominent from The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, essentially a psychological thriller wherein Okada Kumiko gradually loses her sense of identity in the other world, but once more has its roots in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, in which the inhabitants of the Town, once their shadows have died, lose all sense of who they are, or were, as well as their relationship to others in the physical/conscious world. This is likely what Murakami means when, in his two-story house metaphor, he says that one ought not spend too much time in the subbasement, for the longer one spends down there (“over there”), the less likely one is to return to “this side” with any concrete sense of who one is. From Kumiko and Lt. Mamiya in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle to Nakata in Kafka on the Shore, Murakami fiction is littered with the shattered empty shells of characters whose shadows have been left behind in—dissolved into—that daunting realm.

Before exploring the manner in which the physical and metaphysical worlds function in the various texts to be examined in this and later chapters, I will briefly describe how these worlds connect with one another and how each is accessed by the various characters who populate Murakami fiction. And while it would be overly simplistic to characterize these realms purely and simply in the psychological terms of conscious and unconscious, certain aspects of the Freudian and Jungian models of the psyche will prove useful in showing the true nature of the “other world,” even in its more mystical/spiritual aspects. Indeed, one recalls that Jung himself, from his early writings, acknowledges a close connection between the human psyche and the human soul, lamenting that the price of our modernity has been the loss of our spiritual awareness:

We moderns are faced with the necessity of rediscovering the life of the spirit; we must experience it anew for ourselves. It is the only way in which we can break the spell that binds us to the cycle of biological events. My position on this question is the third point of difference between Freud’s views and my own. Because of it I am accused of mysticism.6

Later in life, in a series of informal reminiscences (many of which, incidentally, describe visions that are unquestionably mystic in nature), Jung notes that “the soul, the anima, establishes the relationship to the unconscious. In a certain sense this is also a relationship to the collectivity of the dead; for the unconscious corresponds to the mythic land of the dead, the land of the ancestors.”7 For Jung—and for Murakami—the inner psyche and the “other world” share certain characteristics and might even be conflated into a single entity.

Murakami’s early works, on the one hand, show greater similarity to a Freudian model of the mind, in which the individual psyche exists autonomously, disconnected from other minds except in the conscious realm. In these works—up to (but not including) The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle—the protagonist gains access to his own individual inner mind, a metaphysical realm that is entirely his own, and the memories he meets there are equally connected to himself alone.8 When Boku enters Rat’s mountain villa at the end of A Wild Sheep Chase, for instance, and has a long conversation with the dead Rat, he has entered a space that cannot be accessed by anyone else. This, more than any other reason, is why his ear model girlfriend must be sent away shortly after their arrival at Rat’s mountain villa near the end of the novel.

From The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle onward, on the other hand, the metaphysical world is thrown wide open, depicted as a kind of “shared space” to which all characters appear to have access, wherein they meet, engage one another, and return to “this side.” In psychological terms this may be viewed as a shift from the Freudian model to the Jungian one; in metaphysical terms, it permits Murakami a considerably wider range of imaginative depiction for the “other world,” for what was personal, individual memory is now a collective one— the Narrative—that grounds all humanity from the beginning of time. In Jungian terms this is the “collective unconscious”; a mystic would call it the anima mundi, or “world soul.”

Having reached this point in our general description of the “other world,” we can now usefully examine some of the specific depictions of that world in Murakami’s fiction, from early to recent. These examinations will reveal the gradual but noticeable development of both the “other world” to which the Murakami hero gains access, and the hero himself, whose ability to recognize, access, and manipulate the “other world” grows proportionally with Murakami’s ability to write it.

Martian Winds and Wells: Hear the Wind Sing

Our first glimpse of the metaphysical realm comes rather tentatively in Hear the Wind Sing, which follows “Boku” through a period of eighteen days in late summer of 1970. Boku’s summer is spent drinking beer at J’s Bar and attempting to make friends with a rather difficult young woman who has only nine fingers. The woman—barely more than a girl, really—has some cause to be difficult with Boku, who has a significant advantage when they first meet: he is wide awake, having brought the woman home after she had too much to drink the previous night. She awakens to find herself in her bed, naked, with Boku watching her, and is thus understandably mistrustful of his intentions.

In numerous ways the nine-fingered girl serves as a prelude to Naoko, the tragic heroine of Norwegian Wood. Like Naoko, whose first and only experience with intercourse is followed by a rapid decline in mental health, the nine-fingered girl has been injured sexually—in fact, she is pregnant but has no idea when this happened or with whom. Also like Naoko, the nine-fingered girl hears voices from “over there” urging her to die. “‘When I’m all on my own and it’s quiet, I can hear people talking to me. . . . people I know, and people I don’t. My father and mother, my teachers in school, all sorts of people. . . . It’s usually horrible stuff—like that I ought to get on with it and die—and then they say dirty things, too.’”9 What these “dirty things” are is not made clear, but it is quite obvious that these messages of death and (presumably) sexuality represent the uninhibited voices of her id.

Further, the nine-fingered girl is not the only character in this novel to hear the spectral voices emerging from the metaphysical realm. The work takes its title from a scene (in an embedded narrative by the fictitious writer “Derek Hartfield”) wherein a boy jumps into a seemingly bottomless well on Mars, seeking the ultimate abyss. As he falls deeper and deeper, he begins to feel a sense of benevolence from the well, his body gently enveloped in its peculiar strength. At last he enters a side tunnel and walks along it for an indeterminate period; it may be hours or even days, but he cannot judge, because his watch has stopped and he feels neither the hunger nor the fatigue that would indicate the passage of time. Eventually the boy locates an adjacent tunnel and climbs back to the surface, where the wind whispers to him that he has been in the well for more than 1.5 billion years. “‘That tunnel you came out of was dug out by a time warp,’” the wind goes on. “‘So we’re wandering around in between time. From the Big Bang to the Big Crunch. For us there is no life or death. We are the wind’” (1:97). The boy then asks the wind what it has learned in this endless wandering but receives only a sardonic laugh in return, whereupon he puts a gun barrel into his mouth and pulls the trigger.

This, then, is our first glimpse of the Murakami metaphysical world, which we might not recognize as the unconscious, however, until the boy expresses wonder that the wind can talk, and the wind replies, “‘Me? You’re the one talking. I’m just giving hints to your inner self’” (1:97).10 Tsuge Teruhiko, who points out the homonymic relationship between “id” and ido, identifies the wind as the boy’s own unconscious voice:

The “wind” that emerges here is the narrative of the youth’s inner self, which has escaped from the “id” (ido). . . . If we take this “wind” as a metaphor for Jung’s “collective unconscious,” the meaning of the work’s title becomes quite clear. . . . The wind’s message to the boy is to “listen to the voice of the collective unconscious that has arisen through your individual unconscious.”11

Invocation of the voice of the “individual unconscious” connects effectively with the notion of the “inner narrative” noted in the previous chapter, but what is the boy to have learned from the wind? Murakami once described his earliest works as expressions of the confusion experienced by his generation in the aftermath of the 1960s.12 That confusion is clearly evident in this novel, whose nihilistic message seems to be that life is meaningless, a realization that leads the boy to despair, and death.

Into the Chilly Gloom: Pinball, 1973

The “other world” receives a more concrete description in Pinball, 1973, a work structured through parallel narratives that depict, alternately, the movements of Boku in Tokyo (now running a small public relations firm with a friend) and Rat, from whom he is now permanently separated. It is through the Rat sequences that we find the “other world” emerging.

Many commentators on the Rat trilogy have argued that Rat is a doppelganger figure to Boku, his dark, brooding, yet outspoken inner self. He is best thought of as a kind of inner voice, a companion for Boku, who is almost pathologically withdrawn from the world around him. The extent of his interiority is hinted early in Hear the Wind Sing when we learn that Boku as a child was so quiet as to be virtually mute. Then, quite suddenly at the age of fourteen, “I suddenly started talking, like a dam had burst. I don’t remember what I talked about, but I talked nonstop for three months, like I was filling in fourteen years’ worth of blank space. Then, in mid-July, I developed a 104º fever and took three days off from school. After that I became your average fourteen year-old boy, neither mute nor chatterbox” (1:26). We see here the buildup of internal, psychic pressure, a “venting” of sorts, followed by the restoration of a sense of balance between the two worlds. And yet, throughout the Rat trilogy we see that Boku maintains the habit of saying no more than necessary. And most of what he really needs to say is addressed to Rat and “J,” the Chinese owner of the bar where he and Rat drink. This is slightly misleading, however, because neither of these two characters actually exists in the world outside of Boku’s mind.

It is highly tempting when reading nearly all of Murakami’s works to overschematize the events and relationships that emerge in those narratives. This is particularly true of the relationship that forms between Rat and Boku, whose parallel narratives seem to point us toward some symbolic or thematic revelation about them. One celebrated attempt at such schematization was performed by Katō Norihiro, one of the more prolific Murakami scholars, who attempts to chart out the movements and events that befall each of these characters.13 Such exercises are unfailingly entertaining and all but irresistible, but in this case pointless because Rat is never actually alive, in the physical sense of the word, within the pages of any of the novels that form the Rat trilogy. Rather, Rat exists—and has always done—as part of “the town” (machi), presented to us as Boku’s hometown but in fact nothing more than his memory of the place where he passed his youth.

There is considerable evidence to support this argument. Early in Hear the Wind Sing Boku describes his first meeting with Rat. The year is 1967, the same year Boku begins university in Tokyo. Boku has no recollection of how he and Rat were introduced but recalls being in Rat’s Fiat 600 sports car, blind drunk, tearing down a rural road at more than fifty miles per hour, when they went through a fence and slammed—still at full speed—into a stone pillar at a park. Although the Fiat is completely destroyed, neither man has a mark on him. After Boku pulls Rat out of the wreckage, the two buy more beer, then drink it by the seashore, possessed by an uncanny sense of strength.

So how did they even survive this crash, let alone emerge without a scratch?

The answer is, of course, that the “crash” took place in the “other world,” where neither alteration nor death can occur. It is something like having an accident in a dream; eventually one awakens. Boku eventually wakes up in the physical world; Rat remains where he belongs and has always been: “over there.”

Whether Rat ever existed outside of Boku’s mind is another matter, and one for which no definitive answer is possible. There is a flashback in Pinball, 1973 in which Rat thinks back to the spring of 1970. “For Rat, the flow of time had gradually begun to lose its consistency three years earlier. It was the spring he had dropped out of college,”14 we are told, but are we truly reading the narrative of Rat here, or is this the story of Boku himself? The corruption of time may as easily signal the moment at which Boku’s (outer) world begins to close itself off from Rat’s (inner) world, leaving the latter trapped and isolated. This puts into clearer perspective the “final” meeting between Rat and Boku, at Rat’s mountain villa in Hokkaido at the end of A Wild Sheep Chase, as well. Rat begins their meeting by announcing that he is already dead, having hanged himself a week earlier, but the mountain villa is merely one more manifestation of the “other world,” and to hang oneself in that realm carries no more meaning than to crash one’s Fiat into a stone pillar there. It is, finally, just one more death in the dreamscape, nothing more.

If the Rat sequences, as I have contended, take place solely in the “other world,” then what sort of a place is it? On this point we have considerably more detail. The “town” from which Boku comes, and to which he returns periodically, is dominated by an atmosphere of gloom and stagnation, and other characters who turn up there—including Rat—are part of that atmosphere. This includes J, the bartender who looks after Boku and Rat in all three novels. Interestingly, J confides to Boku in Hear the Wind Sing that he has not set foot outside the town “‘since the year of the Tokyo Olympics’” (1:115), suggesting for us that the year of his death (or at any rate Boku’s last time to meet him) was 1964. In a similar fashion “the woman,” with whom Rat carries on a rather melancholy relationship, reminds us of a lost soul, crushed by a sense of loss and desolation. As they take a “romantic” stroll one evening near a seriously depressing cemetery, she leans heavily on Rat, barely moving, somewhere between sleep and death. The cemetery itself forms an effective microcosmic depiction of the “town” itself:

The cemetery looked less like a collection of graves than a town that had been cast aside. More than half the plots were empty. Those for whom this ground was reserved were still living. . . . The cemetery was a place that had had special meaning for Rat when he was young: back before he could drive a car, he had brought girls up the river path to this place on his 250cc motorcycle any number of times. . . . So many scents had come to him, then disappeared. So many dreams, so much sadness, so many promises. Now they were all gone.15

Scenes such as this, as well as the ever-present images of the harbor lighthouse at dusk—a place Rat (Boku) used to play as a boy—and the dim glow of the streetlights, lend the text a sense of nostalgia and of decay, leaving us in little doubt that Rat, from the very start, has existed in the realm of memories, the land of the dead.

At the same time, this metaphysical realm is always connected to Boku’s waking world as well, for it remains a part of Boku’s overall psyche. That Boku’s present girlfriend (the “nine-fingered girl”) in Hear the Wind Sing is narratologically linked to the girl Rat carries around with him on the other side is strongly suggested from the respective scenes in which two women are initially encountered. In each scene we notice that both women are physically appraised while sleeping, defenseless, and in both cases we are given the impression of a healthy facade masking inner fragility, physical and mental. Here is the introduction of the “nine-fingered girl” in Hear the Wind Sing:

I leaned against the headboard, naked, and after lighting a cigarette took a good look at the woman sleeping next to me. She was bathed in sunlight shining through the south-facing windows, sleeping soundly with the towel that had covered her pushed down to her feet. Occasionally she’d breathe hard, and her nicely shaped breasts rose and fell. She was well tanned, but it had been a while, so the color was starting to turn a bit drab, and the part normally covered by her swimsuit stood out in white, and looked like rotting flesh. (1:27)

And now Rat’s girlfriend:

She had small breasts, and her body, devoid of excess flesh, was nicely tanned, but it was a tan that looked somehow like she hadn’t meant to get a tan. Her sharp cheek bones and thin mouth gave the impression of a good upbringing and inner strength, but the slight changes in expression that flitted through her body betrayed a defenseless naïveté deep inside.16

The initial description of Boku’s “nine-fingered girl,” in fact, with its mixture of good health (“nicely shaped breasts”) and of death (“rotting flesh”), intimates her simultaneous existence in both worlds—that of the living and of the dead; Rat’s girl, with her ambivalent combination of “inner strength” and “defenseless naïveté,” signals a similarly dual existence. Are they the same woman? Has the “nine-fingered girl,” by the time of Pinball, 1973, finally listened to the voices from the “other world” and joined them? If only Rat had taken the trouble to examine her hands instead of her breasts!

Passages to the World of the Dead

These depictions of the “other world” continue to develop in A Wild Sheep Chase, the third work in the Rat trilogy. As noted earlier, A Wild Sheep Chase is an adventure tale in which the protagonist embarks on a quest for a semimythical, all-powerful Sheep. Boku’s quest for the Sheep is, of course, really only symbolic, for the true object of his search is Rat himself, and so when at last he discovers the one, he also finds the other, at Rat’s mountain villa in the wilds of Hokkaido. This villa we may view as the “core” of Boku’s inner mind.

Two separate descriptions of a journey highlight the descent into this metaphysical realm: first is a history of the town of “Jūnitakichō” and its settlement in the nineteenth century by farmers on the run from their creditors; the second is the trek carried out by Boku and his ear model girlfriend, which takes them first to Sapporo, then to Jūnitakichō, and finally to the villa. Both of these journeys are marked by fear and hardship. For the nineteenth-century farmers, it means months of hiking, led by an Ainu youth, across mountains and tundra, and the farther they move into the wilderness, the less fertile and hospitable they find the land, until they reach the site of present-day Jūnitakichō, little more than an infertile swamp filled with mosquitoes, plagued by swarms of locusts. It might as well be the end of the world, which suits the fugitives fine.17

The journey undertaken by Boku and his girlfriend is less arduous, to be sure, but also contains its moments of danger, for theirs is both real and symbolic, a journey of passage from the world of the living to that of the dead, what Japanese literary convention terms the michiyuki. This “passage”—an essential part of classical Japanese theater, particularly in love suicide plays—is undertaken to prepare the travelers for death. For Boku and his girlfriend, it amounts to a long walk along a perilous road, complete with howling winds and the fear that the ground itself might crumble away and swallow them up. This is not lost on Boku, who reflects that “it was like we had been deserted at the very edge of the world.”18 As they begin their hike through this mountain pass, Boku considers further that the mountain scenery in the distance “was certainly splendid, but looking at it brought no pleasure; it was too cold and distant, and somehow wild” (2:292). Moving forward along the road to a tight curve famous for being treacherous after the rain, Boku senses its malevolence:

As the caretaker had said, there was definitely something ominous about the place. I had a vague sensation of its ill will in my body, and soon that indistinct bad feeling was setting off alarms in my head. It was like crossing a river, and suddenly stepping into a much colder bit of water. (2:293)

His instincts are quite correct, as each step takes him farther into the forbidden land of the “other world,” closer to the very center of his inner mind, the land of dreams, memories, and even death. As they move beyond the treacherous “dead man’s curve,” they find themselves in a vast plain, at the center of which rests Rat’s villa. (With a little imagination Boku’s “river” above might be named “Styx,” and this plain “Elysium.”) Although the villa looks impressive from a distance, its age becomes more visible as they approach. “It looked a lot bigger than it had from a distance, and a lot older” (2:297), and the door opens with “an old-fashioned brass key that had turned white where hands had touched it” (2:298). Inside the villa, the furnishings are a monument to a bygone era. “By the window were a desk and chair of a simple design you wouldn’t often see these days,” and in the drawers, “a cheap fountain pen, three spare boxes of ink, and a letter set” (2:301). The bookcases are lined with “basic reading matter for an intellectual forty years ago” (2:302). Simply put, this is a place forgotten by time, a time capsule from the early 1940s.

Not long after their arrival at the villa, Boku’s girlfriend disappears without a trace, and in her place appears the Sheepman, a bizarre, filthy little man in an even filthier sheep suit who speaks rapidly and irritably (the English translation cleverly removes the spaces between words, lending him a comic air that almost outdoes the original). The Sheepman explains to Boku that his girlfriend needed to leave because “‘she shouldn’t have come in the first place,’” adding that “‘you aren’t thinking about anyone but yourself’” (2:316). But what does this mean? One senses that more than telling Boku he is selfish, the Sheepman is reminding him that this is his own mind, and that only he is entitled to the thoughts and memories that exist here. In other words, insofar as the core of one’s consciousness is the most intensely personal place that can exist, to bring another into it is by definition inappropriate. This is why the ear model is “confused,” as the Sheepman puts it.

The Sheepman himself, on the other hand, is constructed from a variety of memories in Boku’s mind, principally Rat and the Sheep, but also the information he has gleaned from his conversations with the Man in Black, the Sheep Professor (who was once possessed by the Sheep), and from his readings on the history of Jūnitakichō, including the story of the Ainu youth, who surfaces briefly in the Sheepman’s comments against war.19 In the main, however, the Sheepman is comprised of Rat and the Sheep, and it is through him that Boku communicates his desire to meet Rat as soon as possible.

When he finally does meet Rat as Rat, their meeting takes place at night in the villa, now perfectly dark and freezing cold, much like the warehouse in which Boku found the Spaceship in Pinball, 1973, but thanks to the darkness, Rat is able to emerge as himself rather than as the Sheepman. He explains himself as well as he can, including the fact that he is already dead, but as noted earlier, this does not matter, since death holds no lasting meaning in the “other world.” This is hinted at the end of their conversation, in fact, when Rat tells Boku, “‘I’m sure we’ll meet again’” (2:259), and in truth, there is no reason why this should not be so, for death is clearly not the end of the road in this realm of timeless Time.

Metaphysical Realism: Norwegian Wood

If A Wild Sheep Chase ranks among the most heavily metaphysical of Murakami’s novels, his 1987 best-selling Norwegian Wood is among the most realistic, and indeed the author has stated on many occasions that he intended all along to write a “realist” work.20 Part of this realist approach lies in his style, which, at least in its dialogue, is largely devoid of the lyrical, almost fantasy-like speech used by inhabitants of “the Town” in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, or some of the absurdist conversations that occur between Boku and the Twins in Pinball, 1973. Yet even in the “straightforward” writing style of Norwegian Wood, according to some, the realism is lost. Odaka Shūya, for one, notes that the “straightforward” discussion of sexuality, particularly by a nineteen-year-old protagonist like Watanabe Tōru, is anything but realistic, and “quite the reverse, that characteristic of conceptualized frankness obscures what the author terms a ‘realistic novel’ as a whole.”21

But style alone does not determine whether a work should be characterized as “realistic” in any case, and much in Norwegian Wood precludes such a claim. It is true that Murakami, in this instance, abandons the dualistic narrative structure of many of his earlier works, in which “this world” and the “other world” are clearly separated, each portrayed separately; it is equally true that we find none of the bizarre, otherworldly characters in it—no Sheepman, no Twins, no talking pinball machines. Everything that occurs in this novel can be explained in terms of physics and (aberrant) psychology, if this is what one chooses to do; in fact, any of Murakami’s novels could be read in this way, simply as hallucinations, intense psychotic episodes on the part of their protagonists. But where would be the fun in that?

Much may be gained from the reading experience, on the other hand, if we admit that the constant presence of the metaphysical world in this work, thinly disguised as dreams, hallucinations, schizophrenia, and what appears to be madness on the part of the novel’s heroine, may, in fact, be read just as effectively as the same awareness of that presence shown by every other Murakami hero. We do see, however, a new phase in the construction of the “other world,” one in which the metaphysical world lurks beneath the surface of the text, at key moments subtly but inexorably drawing nearer the physical one, exerting its influence, drawing those in the physical world into itself.

The plot of Norwegian Wood is straightforward enough: Kizuki is a close friend of Watanabe Tōru, and Naoko is Kizuki’s lover—his soul mate, in fact. Their relationship is physical, but it does not include actual intercourse, the reasons for which are never stated in the novel. Without warning, Kizuki commits suicide, leaving Naoko alone with Watanabe Tōru, who cares for her the best he can, but the death of Kizuki has left her, like so many Murakami characters, feeling as though she has lost half of her self.22

Both Naoko and Tōru attend university in Tokyo—she at a college for well-bred young women, Tōru at a more general university—and when Naoko is emotionally stable, they spend their Sundays together, saying little, but taking comfort in one another’s presence, quietly mourning the absence of Kizuki. Finally, on her twentieth birthday, the physical gateway to Naoko’s metaphysical world—here represented through her sexual organs—opens up, and she engages in intercourse with Tōru. It is her first and last time. Not long after this she is sent to a remote sanatorium in the mountains, where Tōru visits her twice. Just as it seems she may be on the mend, however, Tōru receives word that Naoko has committed suicide, hanging herself from a tree in the woods adjacent to her sanatorium.

Tōru’s journeys to this location should interest us here, for they bear many of the same markings as previous forays into the metaphysical realm we have already seen. Starting from the northern part of Kyoto, he rides a bus, which carries takes him farther and farther away from inhabited areas, until they enter a valley—just one more well, elevator shaft, telephone line—where the bus driver must tack the bus back and forth along a twisty, uncomfortable road. At length they enter a wood of cedars, where the chill uneasiness of the “other world” becomes noticeable: “the wind that came through the windows of the bus suddenly became cold, its dampness painful on my skin. We ran along the river in that cedar wood for a long time, and just when I was starting to think the world had been buried in an endless expanse of cedar woods, we came out of it.”23 This description is strongly reminiscent of the michiyuki we saw in A Wild Sheep Chase and suggests that Tōru has now traveled to the world of the dead (or at least its antechamber) to find his beloved. The gate to the sanatorium is protected by a guard, yet another common feature of the entrance to “over there.”24

Naoko herself is by this time already perched precariously between the worlds of life and death. This is strongly hinted at two points: first, when Tōru awakens from a peculiar dream to find her seated at the foot of his bed; and second, when Naoko admits to hearing Kizuki calling her from “over there,” inviting her to join him. In the first scene, each detail suggests Tōru’s absorption into the world Naoko inhabits: he gropes for his watch but cannot find it (human-made time does not exist here); the moonlight is bright, but its light cannot penetrate every corner, causing a strong contrast between shadow and light; and Naoko herself is clearly not the Naoko he is used to seeing. “With a faint rustling of her nightgown she knelt beside my pillow and stared into my eyes. I looked at her eyes too, but they said nothing to me. They were unnaturally clear, as if you could see right through them into the world over there, but no matter how far I looked, I couldn’t see all the way to the bottom.”25

But her eyes are not the only things Tōru finds unusual about Naoko; her body, too, is unnaturally perfect, as though she were a kind of idealized copy of the real Naoko.26 He tries to reach out and touch her, but she moves away from him, as though fearing the touch of the physical world, for this is her metaphysical self revealing itself to him. Tōru is literally seeing Naoko’s spirit, her very soul, freed from her body by the night and by her proximity to the world of the dead. Her spirit is strong here because she has already completed her own michiyuki and now stands (or at least sits) at the gateway to the underworld. Her efforts to explain this to Tōru would seem to confirm this:

“If I’m so twisted up like this that I can never get back, I’m afraid I’ll just stay like this, growing old here and rotting away. When I think about that, I feel like I’ll freeze right to the core. It’s horrible. Painful, freezing. . . . I’d swear I can feel Kizuki reaching his hand out of the darkness to me. ‘Hey, Naoko, we can’t be apart,’ he says. I never know what to do when I’m told such things.”27

When Naoko says she can “never get back” (modorenai), she means not the everyday world of Tokyo but returning to the world of the living from that of the dead. It is only a matter of time before Naoko takes heed of Kizuki’s call, takes that one final step, and joins him fully in death, as indeed she does near the end of the novel.

We see, then, that even within this so-called realistic novel, Murakami employs many of the same markers he uses in his magical realist fiction to indicate the borders between the physical and metaphysical worlds; perhaps even he cannot prevent the intrusion of the metaphysical realm on what we might concede to be a comparatively realistic narrative. Possibly the author meant this to be a more psychological penetration, a look into the mind of the schizophrenic, but in the end he proves something rather less empirical, namely, that behind our scientific approach to the mind lies the primordial memory of something less subtle but no less real: our awareness and dread of the mouth of the cave that leads beneath the earth, where the souls of the dead await our arrival. We recognize yet again that for Murakami, wittingly or not, the world of the unconscious and the metaphysical land of the dead are finally inseparable.

The Unconscious “Shared Space”: The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

Because Murakami aimed at a quasi-realism in Norwegian Wood, we find none of the peculiar transformations that mark passage between the physical and metaphysical realms—Naoko turning into a pinball machine, Rat and Sheep combined into Sheepman, and so forth—in that novel. Naoko, whether in Tokyo or her mountain sanatorium, remains Naoko throughout. By exposing the metaphysical aspects of Norwegian Wood, however, we have also revealed its positioning as a transitional novel between the two models of the inner and outer minds—individual and collective—that have marked Murakami fiction. That is to say, in constructing a metaphysical space in the form of the sanatorium, the author actually develops a prototype for what becomes the norm in his depiction of the “other world,” namely, a realm in which a variety of characters meet one another, interact, and return (or fail to return, as the case may be) to the real, physical world.

This (for Murakami) novel approach to the “other world” is a useful prelude for what he achieves in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, in which the unconscious hotel wherein Okada Tōru’s wife, Kumiko, is held captive is presented as a sort of hub for all human consciousness, a dimension that not only transcends the limitations of physical time and space (as previous manifestations have done) but now allows access to all characters, who are free to cross the boundaries of history, even of life and death itself, interact, and even interchange with one another, in the metaphysical maze. It is within this unconscious hotel, this metaphysical shared space, that the final conflict between Okada Tōru and his archenemy/doppelganger Wataya Noboru will be played out for the sake of Kumiko’s inner self.

Our first view of the hotel from Tōru’s point of view comes shortly after his first meeting with Kanō Creta, who has just finished telling him about her early life, marked by constant, unendurable pain, her attempted suicide—like Rat, she drove a car at full speed into a solid object—and the beginning of a new life afterwards, including her time as a prostitute. This last presumably plays a role in what happens in the chapter that follows, when Tōru dreams of being in the hotel for the first time. At a bar where he has just ordered a Cutty Sark, he is accosted by a man with no face, who leads him to Room 208 of the hotel. His impressions of the room are reminiscent of Boku’s description of the anachronistic fixtures of Rat’s villa: “a spacious room. It looked like a suite in an old hotel. It had a high ceiling, with an old-fashioned chandelier hanging from it. But the lights in the chandelier were not on. Only the small wall lamps gave any light to the room. The window curtains were tightly shut.”28 Tōru’s drink at the bar having been interrupted, the faceless man invites him to have one out of the liquor cabinet by the door, but when Tōru attempts to open the cabinet, he discovers that “what had looked like doors were all skillfully made false doors” (1:187). Following this, he realizes Kanō Creta is in the room with him. Without hesitation she strips off her clothes and fellates him with consummate, professional skill.

This description contains numerous points of interest, among them the identity of the “faceless man,” a character who will return in the novel After Dark. What is the role of this peculiar character in this narrative? Jungians no doubt begin to salivate, Pavlovian-style, at the appearance of the faceless man, and would link him to Jung’s anima/animus, and one suspects that such an analysis would bear considerable fruit.29 In certain ways he resembles a trickster spirit: he promises to guide Tōru to the room he seeks, but then hands him a pen light, tells him to mix himself a drink, only the cupboard doors are only painted on, not real. My own approach, related to this role, suggests that he be read as a mischievous, almost comic keeper/guide to the “other world,” not unlike the Sheepman, but here presented faceless because he must stand in for the unknown inner selves of all people. As such, he must be a neutral character, and while he guides Tōru to the mysterious Room 208, in which Kumiko languishes, he does not go so far as to solve the mystery for him but merely warns him when there is danger. The faceless man’s role is to maintain a sense of balance between the various dichotomies at work here: consciousness versus unconsciousness, physical versus metaphysical, evil versus good, male versus female, passive versus aggressive, asexual versus sexual, order versus chaos. Maintaining balance in all these things, as will be seen shortly, is key to the orderly movement of time and space in the physical world and one of the major functions of the metaphysical one.

This helps us to understand more clearly what Kanō Creta means when she warns Okada Tōru that he and Wataya Noboru cannot live simultaneously; she does not mean necessarily that one of them must die, but rather that they cannot occupy the same world. Tōru and Wataya Noboru represent these various oppositions, and if one of them lives in the physical world, then the other will have no choice but to occupy the “other world.” This also helps us to understand the importance of the motif of war in this text; when Okada Tōru lives in the physical world, “order” prevails, but when Wataya Noboru is turned loose, the result is “chaos”—violence and destruction. This idea will be explored at greater length later in this chapter.

The Body as Vessel

We have already noted that The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle is the first place wherein we see the collective nature of the other world portrayed in Murakami fiction. Why is this so important? Simply stated, it is because a whole new range of movement opens up to Murakami and his characters as a result. No longer confined to the limitations of the individual, seeking in vain to protect a lone identity connected with that individual, in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle Murakami begins to play with the notion of detaching mind from body, to view the body as an interchangeable vessel containing a more permanent—but, in the physical world, invisible and intangible—self.

This idea seems to be on the minds of all the characters in one form or another. Lt. Mamiya, describing himself after the incident in Outer Mongolia, uses the expression “empty vessel,” and in fact his experience in the well could be read as a metaphor for this same idea: he is placed into the earth—the “body” of all living things—and then removed from it, a “core” with no body. In the same manner, somehow Lt. Mamiya’s “core” has been removed from his body, leaving him empty. Kanō Creta, similarly, explains to Tōru the odd sensation of having somehow separated her mind from her body following her unsuccessful suicide:

“My body felt terribly light. I felt as if I were floating, like this wasn’t my own body. It was as though my soul had inhabited a body that didn’t belong to me, something like that. . . . a gap had opened up someplace. I was confused. I felt as though I were completely disconnected from this world.” (1:183)

A similar message is passed along to Tōru by an old family friend, yet another clairvoyant, called “Mr. Honda,” but in a rather more cryptic fashion: it is an empty gift box for Cutty Sark whiskey. The box is ornately gift wrapped, but the bottle of whiskey that ought to be inside—the “core” of the gift—is missing. In this gesture Honda suggests the tenuous nature of the connection between mind and body, the impermanence of the flesh that houses the core spirit within, and the ease with which flesh and spirit may separate.

And in the second half of the novel, this is precisely what Tōru aims to do. Seated at the bottom of his own well, he attempts to separate his body and his “core” from one another. “Just as I do when I am with ‘those women,’ I try to separate from myself. Crouched in the darkness, I try to escape from this awkward body of mine. I am nothing but an empty house now, nothing more than a cast off well. I am trying to transfer to a reality that runs at a different speed” (3:100). That “different speed” is, of course, a dead halt in time, during which time not only Tōru but others slip into something more astral and gather for a game of “musical bodies” in the unconscious hotel. This is more or less what occurs when Tōru dreams once again that he is making love to Kanō Creta in Room 208 later in the novel. She still wears a dress belonging to Kumiko, but as she writhes atop him, the room goes dark, and Tōru hears her speaking to him in the voice of the “telephone woman.” And although this is a dream, we begin to have an inkling of what is really happening: in this dream world, people can and do borrow one another’s forms, quite as if the outer body were really nothing more than a hollow shell, a suit of armor hiding the “true” self within.

That motif is given considerably more disturbing expression at the end of book 1, when Lt. Mamiya tells a story about his days in Manchuria during World War II. Mamiya is part of a reconnaissance team infiltrating enemy territory across the Mongolian border. Their team is captured by Mongolian troops, led by a sadistic Russian. In the course of interrogation, Mamiya’s team leader, an intelligence officer known only as “Yamamoto,” is staked to the ground by his captors and slowly skinned alive. It is a singularly gruesome scene and at the time seemed rather out of place in Murakami’s ordinarily easygoing narrative world. Why, of all things, would he have chosen skinning as the method of death? The answer, of course, is that this merely takes to a more physical level the notion of gaining access to the “core” identity. In their efforts to reach the truth—in effect, Yamamoto’s “true” self—his captors literally remove his outer skin to reveal the genuine core lurking inside. A different, but related, sort of mutilation occurs in book 3 when the father of “Cinnamon,” son of “Nutmeg,” is murdered, his body discovered in a hotel room with all its internal organs removed. This is more than gratuitous mutilation; the removal of his organs indicates an attempt to remove his “core,” while the outer shell of his body was cast aside.

This, then, presents to us an interesting progression in Murakami fiction: whereas in works like A Wild Sheep Chase, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, and Dance Dance Dance the Murakami hero struggles to protect his core identity from internal, metaphysical attack, later works reveal their equally desperate struggles to defend the physical shell that houses that core, against enemies whose methods have grown more extreme.

Against these acts of violence, these aggressive attacks on the physical manifestation of the human soul, there is finally no defense; the only salvation for victims of such violence is the recovery of their “core” in the “other world,” and it is to this end that Tōru and his fellow cast members slip in and out of the various physical vessels that house them. This is why Tōru keeps climbing down into his dry well, attempting to cast off his “awkward body.” Iwamiya argues that Tōru’s attempt to change himself into what she calls his “invisible” form is an indispensable step in his quest to rescue Kumiko, for it is her inner self, rather than her body, that must be saved:

Even in the improbable event that the two were able to meet, there would likely be nothing [Tōru] could do to rescue her. Without rescuing Kumiko’s “invisible form” from the world of darkness, her spirit will not return to this world. To this end, Tōru himself must assume the “invisible form” in order to resist Wataya Noboru’s power.30

One reason for this lies in the essential nature of the inner self, which possesses no tangible form in the physical world; how is one to grasp a spirit, the wind? One must first be a spirit. At the same time, Tōru’s evident dissatisfaction with his body—“this clumsy flesh of mine”—as well as his urge to “change vehicles,” signals his realization that the metaphysical state permits him to cover distances not possible in the physical state. Like Wataya Noboru, Tōru has found the secret to astral transmigration and uses this to gain access to his elusive enemy and destroy him.

Not surprisingly, given the newly collective nature of the “other world,” events that occur “over there” have actual consequences in the physical realm. At the very moment when Tōru beats Noboru to death with his baseball bat in the metaphysical realm, the physical Noboru, many miles away, collapses of a fatal brain hemorrhage. Exactly how this happens was not evident at the time The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle was written, but we gain some insight, in retrospect, from the events that transpire in Kafka on the Shore and 1Q84.

Into the Forbidding Forest

Having considered in some detail the functioning of the metaphysical hotel as unconscious “shared space” in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, it is time to explore the other recurring representation of this realm in Murakami fiction, the labyrinth of the forest. Indeed, among the various metaphorical expressions of the “other world” in the author’s fictional universe, none appears more commonly than the forest. This begins, if we read carefully, from Hear the Wind Sing, with the death of Boku’s “third girlfriend,” who “hanged herself in a wild little stand of trees by the tennis courts one spring break” (1:60). In fact, most of our early encounters with the forest in Murakami fiction are associated with unhappy or unsettling events. In Pinball, 1973, the cemetery to which Rat brings his girlfriend for a walk is laid out at the edge of a wooded area, and after their walk, “the two of them returned to the woods and embraced tightly.”31 Rat’s villa in the mountains of Hokkaido is also surrounded by white birches, which have “continued to grow ceaselessly, in contrast to the aging house.”32 The forest plays an important role in Norwegian Wood, as we have seen, forming the boundaries of Naoko’s sanatorium, a buffer between her world and that of Watanabe Tōru; it is also the setting of her suicide. In South of the Border, West of the Sun, the protagonist, Hajime, reencountering his childhood sweetheart, Shimamoto, accompanies her through forested mountains to pour her deceased child’s ashes into a river. Along the way, Hajime takes note of the crows that seem to be everywhere, their sharp cries unsettling.33

But the forest first becomes a serious part of the setting in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, where it forms a kind of buffer zone between “the Town” in which Boku and his fellow dwellers live, and the high wall that holds them all virtual prisoners. The forest, according to Boku’s friend and advisor, “the Colonel,” is a place to be avoided. “‘Once winter begins, don’t go near the wall. The forest, too. They gain great power in the winter.’”34 He goes on to say that although there are certainly people living in the forest, “‘they are different from us in just about every way you can imagine. But listen, I don’t want you getting interested in them. They’re dangerous’” (4:198). Exactly what makes them so dangerous remains unclear, but eventually we learn that the forest people are those whose shadows were imperfectly removed when they entered the Town, and so they retain traces of memory from the conscious world.

For Boku, on the other hand, his initial, tentative forays into the forest give him a sense of tranquility: “as I moved away from the wall and pressed on deeper into the forest, a strangely quiet and peaceful world spread out before me” (4:199). Still, he recognizes the dangers of venturing too far from the wall, for “the forest was deep, and if once I became lost it would be impossible to find my way again. There were no roads, no landmarks” (4:200). While on one of his excursions, he happens to fall asleep in a forest clearing, and when he awakens, looking up at the wall, “I could feel them looking down at me” (4:203). To whom “them” refers is not clarified in the novel, but we might plausibly surmise that “they” are the other souls who live in this collective repository of memory. In the end Boku helps his shadow—who still clings to life—to escape into a pool believed to lead back to the freedom of the outside/conscious world, but at the last moment Boku himself decides to remain in the woods, to continue searching for traces of his mind. It is an apocalyptic ending, for we have no reason to believe that Boku will ever be reunited with his shadow; at best we may say he has finally made a choice.

In Kafka on the Shore, the forest plays an even more central role as a narrative setting, not only in terms of the detailed description it receives but also for its function as a repository of the collective memories of humanity and a meeting place for those memories. In its role as the “other world,” reprising the metaphysical hotel in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, the forest also serves as a conduit between worlds and as a sort of “changing room” wherein the inner self may leap from one physical vessel to another. Access to this forest, as always, requires a journey, yet the “other world” of the forest also seems to lurk always just beside us, waiting for us to take that one step farther across its boundary, into oblivion.

This journey, in the case of Kafka on the Shore, is made by the title character, Kafka himself. As will be recalled from the previous chapter, having fled from his father’s prophesy to Takamatsu City in Shikoku, Kafka lays low at the Kōmori Memorial Library, where the cross-dressing Ōshima provides him company, counsel, and, when necessary, an escape route. As detectives hunt for Kafka as a “person of interest” following the murder of his father, however, they track him to Takamatsu, eventually coming across the library, and Ōshima, fearing that Kafka may be implicated, takes him deep into the forested mountains of Shikoku outside of Takamatsu City. There, at a tiny, secluded cabin owned by Ōshima’s easygoing surfer brother, Kafka spends a few days in seclusion, warned by Ōshima not to wander too far into the forest, as he might never find his way back. As a cautionary tale, Ōshima tells him about two deserters from the Imperial Army during World War II who escaped into the forest, never to be seen again.

In time, of course, Kafka does enter the forest, marking trees with spray paint as he goes, like Hansel and Gretel dropping bits of bread. During his initial stay at the cabin he explores slowly and methodically, venturing slightly farther each day into its murky depths. Even here, at the edge of the metaphysical world, he senses something powerful and mysterious. The description is remarkably like that of the protagonist in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World:

Like yesterday, the forest is dark and deep. The towering trees surround me like a wall. In the gloomy hues, something hidden among the trees, like in an optical illusion picture, is observing my movements.35

Not until the end of the novel, however, does Kafka finally penetrate deeply enough to discover those who actually reside in the metaphysical realm of the forest. Initially, he meets up with two soldiers—the same two who disappeared during World War II, and although the war has been over for decades, both appear exactly as they were the day they deserted from the Imperial Army. They lead Kafka into a dense part of the forest, eventually coming upon a small cluster of cabins deep in the woods. One clever narratological detail worth noting here is that although the soldiers speak to Kafka and he asks them questions, Kafka’s utterances are not set off by quotation marks; we may conclude from this that Kafka’s utterances are really thoughts, for his mind is directly hardwired into the collective unconscious represented by this forest. Much as we see in the latter pages of Hear the Wind Sing, as Kafka converses with others, he is also conversing always with himself.

When Kafka finally does reach the village, he is mildly surprised to find that it has electricity supplied by wind power, and even electrical appliances, though they are uniformly fifteen to twenty years out of date and look as though they had been taken out of trash dumps. This suggests that the metaphysical world—or at least this little part of it—has been closed off since the 1960s, presumably when Saeki and her boyfriend opened and closed the “Gateway Stone.” Since that time, the village has remained isolated, blocked from receiving fresh input. (The repetitive showing of The Sound of Music on the television Kafka discovers would seem to suggest the year 1965.) That fresh, current input (memories) from the physical world is supplied by Kafka himself, and thus the “Saeki” whom Kafka meets there is, simultaneously, the middle-aged woman he fantasizes to be his mother (and with whom he has by now had sexual intercourse) and also the fifteen-year-old girl who first entered that world more than twenty years earlier. The forest will preserve both versions of Saeki forever.

Exploiting the Mind-Body Split

In addition to its function as a repository for memory, the “other world” in Kafka on the Shore serves as a conduit by which characters may cross vast physical distances in this world without ever leaving. This is accomplished through exploitation of the mind-body separation we have already seen in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. In this later work, however, the phenomenon is used to open up the narrative structure to virtually endless possibilities as each character’s true identity grows less and less clear. This is, on the one hand, liberating, as our potential readings of the text increase exponentially depending on how we choose to confront each character; at the same time, much of the complexity—and confusion—in this novel arises from its use of a kind of latticed structure, in which characters with intact inner selves are juxtaposed with those who have no inner self, as well as some who appear to have multiple inner selves. When this inherent confusion of character identity is combined with the overlay—like transparency films placed atop one another—of multiple historical eras in physical time, the tangle grows still worse.

Among the trickier characters in this text is Tamura Kafka’s father, Tamura Kōji, a sculptor who is, for at least part of the narrative, possessed by the spirit taking the form of “Johnny Walker.” But is Johnny Walker actually Kafka’s father, or has he joined the party, so to speak, at some later point? Kafka’s loathing of his father brings this dilemma into sharper relief; is the man Kafka detests Tamura Kōji himself, or is he the spirit we know as Johnny Walker? Kawai Hayao is also drawn to this slippage between identities within these father figures:

Kafka’s real father, Johnny Walker, Colonel Sanders, Nakata—they are all father images. This novel is full of fathers. So it is not so simple as just killing the father and having done with it; no matter how many times the father is killed, he just keeps reemerging in different guises.36

Further, Kafka’s father is not the only tricky issue in this story. Whether Kawai means to argue for shifting core identities, this is precisely what leaves us in so much doubt about who is really who.

One approach to this dilemma is to explore the historical layering of the novel. Each of the three principal characters we meet—Nakata, Saeki, and Tamura Kafka—represents a distinct generation, a discreet historical era, and each at some point in his or her youth, for various reasons, enters the metaphysical world. Beginning chronologically, Nakata first enters this world as a child in 1944, the closing days of World War II, whereupon he loses his “shadow,” in effect, his mind. Saeki, a musician who shared a relationship with a young man very similar to that of Naoko and Kizuki, entered the “other world” during the turbulent 1960s, seeking a place where the chaos of the outer, physical world could not threaten the perfect enclosure in which she and her boyfriend lived; she, too, emerged from this world without her other half—her boyfriend. Kafka, finally, goes “over there” near the end of the novel’s present (concurrent with the novel’s writing), but, unlike the others, escapes with more than he possessed when he entered. The one thing each character’s foray into the “other world” has in common with the others is that it occurs at a moment of chaos and fear: Nakata’s during the conclusion of a disastrous war, Saeki’s during the rising tide of violence attending the antigovernment student movements in the 1960s, and Kafka’s in the face of a more personal crisis, namely, his association by blood with a man he considers to be evil.

Despite their distinct historical epochs, however, these three cases are also linked obliquely by a voice in Kafka’s head, whom he knows as “the Boy Called Crow” (karasu to yobareru shōnen), who guides Kafka in nearly all of his movements away from his father and the prophesy he has received from him. For purposes of this discussion, it is useful to state at the outset that this “voice” very likely represents the shadow lost by Nakata as a child. As such, we will focus our attention chiefly on what actually happened to Nakata on that day in 1944.

Nakata’s entry into the “other world” takes place during something that comes to be known as the “rice bowl hill” incident. Although this incident is narrated through chapters that occur far apart from one another in the text, the narrative may be reconstructed as follows: Nakata’s teacher, a woman whose husband has been killed fighting in the Pacific theater, has a vividly erotic dream about her husband one night. The following day, as she leads her class—Nakata’s class—into the mountains to hunt for wild mushrooms, her menstruation suddenly begins, her blood flow unusually heavy. After cleaning herself as best she can, she buries the bloody towel far from the group, yet not long thereafter finds Nakata standing before her, presenting her bloody towel to her in silence. Possessed by a sudden, uncontrollable rage, she beats him savagely about the face. Shortly after this, a silvery glint is seen in the sky—the teacher assumes it is a lone B-29 bomber, perhaps on reconnaissance. Suddenly all the children collapse in a collective faint. All awaken some hours later, with no apparent ill effects, save Nakata, who remains in his coma for several weeks. When at last he awakens, he has not only lost his memory but the ability to construct new memories as well. He has, however, acquired the ability to speak the language of cats. He spends the rest of his days a ward of his family, and later the state, unable to read or write but useful to the families in his neighborhood in locating lost pets.

If previous Murakami fiction is any guide, we may conclude that like the protagonist of Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World and Kumiko in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, he simply remained for too long in the “other world,” to the point that he could no longer maintain connection with his shadow. In fact, more than once Nakata explains to other characters that he is without a shadow, and so we may view in him an idea of what might have happened to the protagonist of that earlier work if, rather than remaining in the forest that stands between the physical and metaphysical worlds, he had instead managed to escape the Town and return to the physical world without his shadow—one of four possible scenarios Murakami identifies for the earlier novel.37

But what actually happened to Nakata’s shadow after its separation from him in 1944? Did it die? Did it remain in the “other world”? Or did it perhaps find other hosts—other physical beings—with which to join when they happened to wander too far into the forbidden forest and found themselves in the metaphysical world? This appears to be what has happened with Nakata’s shadow, not just once but several times.

If the inner mind or spirit is indeed capable of moving from one body to another, as previous Murakami texts have clearly suggested to be the case, it is not implausible to suppose that Nakata’s shadow has had not one but many lives. How, for instance, might our reading of the novel change if we could imagine that Nakata’s shadow originated with the husband of his childhood teacher (which is why he so unerringly located her menses, a silent communication to her from the dead), and later inhabited not only Saeki’s boyfriend at one time (which would go far in explaining the question of why Saeki tells Nakata that “‘I have known you from a long time past’” [2:293]) but also Kafka himself in the form of “the Boy Called Crow”? Having taken our (admittedly speculative) reading this far, why not suppose that Nakata’s shadow at one time inhabited Kafka’s real father, Tamura Kōji, as well? If Saeki actually were Kafka’s mother, this would help us to understand why she was drawn to him in the first place.

The final piece of the puzzle is, of course, the trickster spirit now calling himself Johnny Walker, for if Nakata’s shadow can move from body to body, so too can Johnny Walker. If we imagine in this work a sort of pursuit, in which the Johnny Walker spirit and Nakata’s shadow chase one another through time, across generations, driving each other from one body to another, we might gain insights into several of the riddles Murakami sets up in this story, among them (a) why Saeki’s boyfriend was killed in Tokyo, and (b) why Saeki left Kafka and his father behind, if indeed she is his real mother.

It may also mean, of course, that Kafka is his own father . . .

This reading is but one of many, intended not to offer a definitive explication of Kafka on the Shore but rather to highlight the extraordinarily open-ended text that results when the fixed nature of the “self”—combining flesh and spirit—is disrupted and the two become separable. But what is the role of the “other world” in this instance? To answer this, we need to look at the moments at which flesh and spirit break apart. This occurs most notably in the chapters in which Nakata, led to the home of Tamura Kōji and Kafka in Tokyo by a large black dog, is confronted with the horror of Johnny Walker’s harvest of cat’s souls.

The sequence, which stretches across three chapters, begins in a vacant lot where Nakata has been waiting patiently, seeking information about a missing cat named “Goma.” While he waits, an enormous black dog approaches him and, without actually speaking, communicates to him that he must follow it. This he does and soon arrives at the home recently abandoned by Kafka. The house itself is protected by an “old fashioned gate,” and upon being led into what appears to be the study, Nakata finds it quite dark (1:214). In the dim light admitted through the closed curtains, he can see only that there is a desk in the room and the silhouette of someone seated beside it. The atmosphere of the room, reminiscent once again of Room 208 in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and the living room of Rat’s villa in A Wild Sheep Chase, marks it as a part of the “other world.”

There he meets Johnny Walker (but not being a drinker, does not recognize his iconic costume), whose description is equally otherworldly, a mass of negatives: “His face had no distinguishing characteristics. He was neither young nor old. He was neither handsome nor ugly” (1:216). He is, rather, just “in-between” all descriptors, marking his place as something belonging neither to “this side” nor to “over there” but to both. He is, however, at present located in the “other world,” and it would seem that the only way he can break free of the metaphysical realm and emerge into the physical is through his own death. This is why he has summoned Nakata.

His choice is an apt one, for mild-mannered though Nakata appears, his self-description as a “man without a shadow,” an “empty shell,” makes him the ideal tool for the job. Nakata’s physical self is, finally, a mere portal, a conduit between the physical and metaphysical worlds, and into his body virtually any force of Will may lodge. However, he must be brought to the proper “temperature” before this may occur. Johnny Walker brings Nakata to his boiling point by committing acts of brutality—of war, as he himself terms it—against the very cats who form Nakata’s circle of attachment. He urges Nakata, likewise, to do his duty as a soldier:

“You have never killed anyone, nor have you ever wished to kill anyone. You don’t have that tendency. But listen here, Mr. Nakata, there are places in our world where that kind of logic doesn’t work. There are times when no one cares much about your tendencies. You need to understand that. Like in war. . . . When war starts, you get taken to be a soldier. When you’re taken as a soldier, you sling your rifle and head off to the battlefield, and you have to kill enemy soldiers. You have to kill a lot of them. No one cares whether you like it or not. It’s what you have to do, and if you don’t, you get killed instead.” (1:246)