6

THE GEOGRAPHY OF CHIANTI CLASSICO

THE LAY OF THE LAND

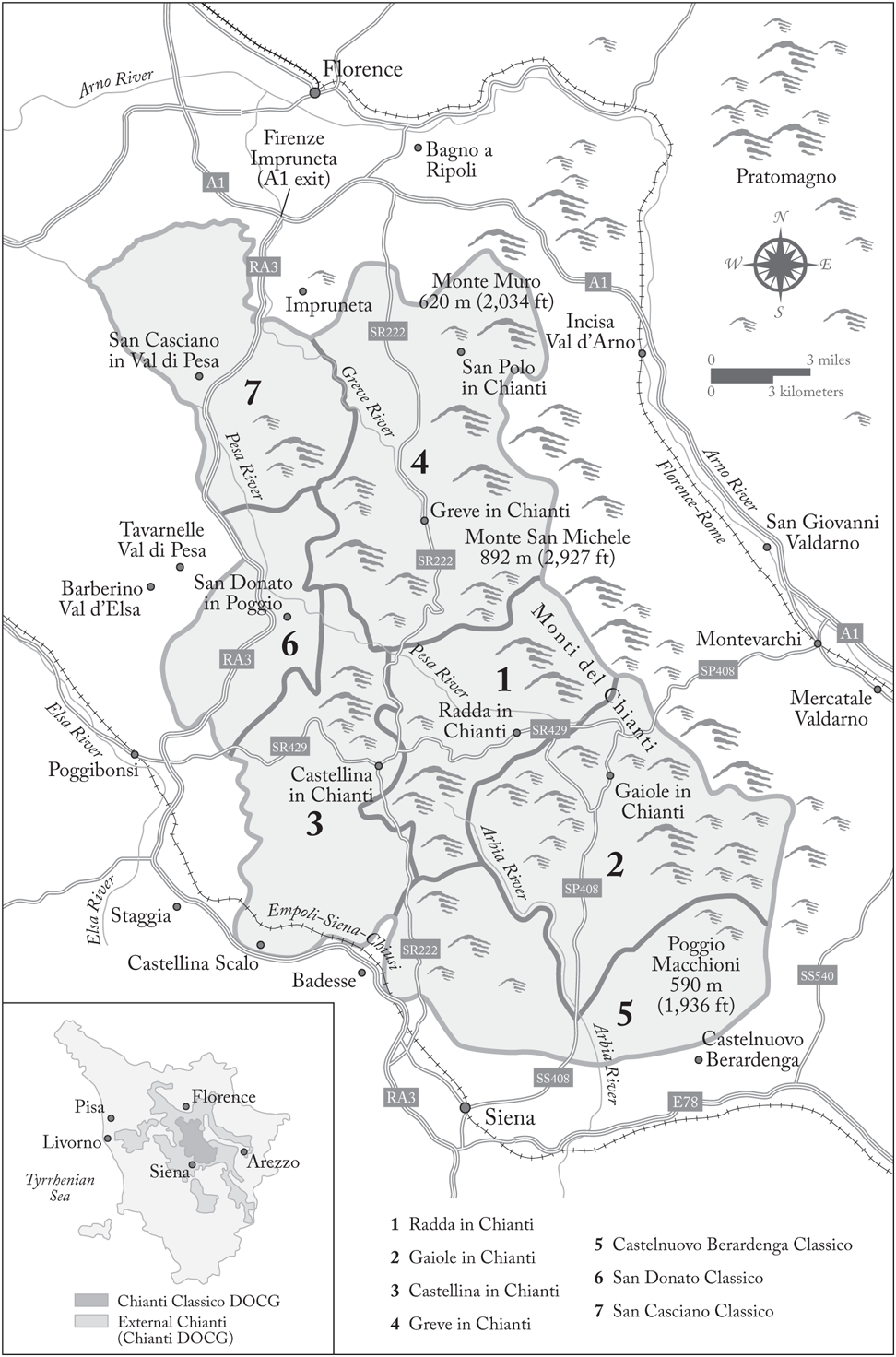

We have just taken you on a personal tour in which you have glimpsed the landscape, vineyards, roads, rivers, valleys, and towns of Chianti. Now we offer you data, information, and ideas that underlie that geographic reality. Chianti Classico is a legal wine appellation in the interior of Tuscany that is about forty kilometers (24.9 miles) long and twenty kilometers (12.4 miles) wide (see map 2, in “Mapping Chianti Classico” below). The area is virtually encircled by two major highways, the Superstrada del Palio (also known as RA3) and the Autostrada del Sole (also known as A1). Knowing where these are helps to delineate Chianti Classico. For first-time explorers (without the benefit of a native and knowing guide), the best way to access any destination in Chianti Classico is to pick the nearest highway exit and drive into the interior. While it is relatively easy to travel on straight roads around Chianti Classico, the routes inside the zone are narrow and banked roadways with no shortage of zigzagging curves. Most of these were first paved only during the 1970s or 1980s. Often, destinations that are near as the magpie flies are far by roadway in Chianti.

Four townships are wholly incorporated in the Chianti Classico appellation: Radda in Chianti, Gaiole in Chianti, Castellina in Chianti, and Greve in Chianti. The denomination includes about half of Castelnuovo Berardenga, half of Tavarnelle Val di Pesa, half of Barberino Val d’Elsa, a small slice of Poggibonsi, and about four-fifths of the township of San Casciano Val di Pesa. In Italy, the administrative divisions, from largest to smallest, are regione (region), provincia (province), comune (township), and frazione (hamlet, which we refer to as localities in this book). The principal town or village in a township often shares the same name with the township. For example, the principal town in the township of Greve in Chianti is also named Greve in Chianti. In Chianti has been legally added to the original name, Greve, in part to associate the town with the well-known, esteemed, and historic name Chianti and in part to distinguish the town and township from others in Italy that are also named Greve. In most cases, a frazione lacks exact geographic boundaries. There are bureaucratic structures and elections at the regional, provincial, and township levels. A località is a named small place (typically smaller than a frazione). It can be officially used in an address. Tuscans call a village un paese. The province usually has the same name as its principal città (city). Hence, there are two Florences, the città and the provincia. The northern half of Chianti Classico is in the province of Florence. The townships of San Casciano Val di Pesa, Tavarnelle Val di Pesa, Barberino Val d’Elsa, and Greve in Chianti are all in the province of Florence. This area is also commonly referred to as Chianti Fiorentino. The southern half of Chianti Classico is in the province of Siena. The townships of Poggibonsi, Castellina in Chianti, Radda in Chianti, Gaiole in Chianti, and Castelnuovo Berardenga are in the province of Siena. This area is commonly referred to as Chianti Senese.

The watersheds of the three largest rivers are Val di Pesa, Val di Greve, and Val d’Elsa. The Pesa, Greve, and Elsa Rivers empty into the Arno River. The Elsa veers northwest away from Chianti Classico after it passes the town of Poggibonsi and then continues northwest by the town of Certaldo before reaching the Arno. Its watershed takes in the southwestern edge of Chianti Classico. The Pesa and Greve Rivers have sources at higher elevations in the center of the Chianti Classico zone and flow roughly parallel as they descend from the heights of the Monti del Chianti (Chianti Mountains). Their watersheds occupy most of Chianti Classico north of the ridge that extends from Badia a Coltibuono to Castellina in Chianti. As they flow to the northwest, the Pesa forms the western border of Chianti Classico from Sambuca to Cerbaia, and the Greve becomes the border between the townships of Greve and San Casciano. A smaller river, the Arbia, flows southeast from its source at Macìa Morta north of Castellina to the city of Siena, eventually meeting the Ombrone. It and its tributaries form the principal watersheds south of the Castellina-Coltibuono ridge. The Massellone, a tributary of the Arbia, has its source in the Monti del Chianti. It runs through Gaiole and the land that for centuries could have aptly been called Ricasoli country. None of these rivers are navigable. Torrents, streams, and creeks that are dry for most of the year fill up with water suddenly after rainstorms. The combination of Chianti Classico’s highly permeable soils and the tendency of these waterways to evacuate water quickly renders agriculture with greater water demands than vines and olive trees challenging.

Of Chianti Classico’s 71,800 hectares (177,422 acres, or 277 square miles), 41,400 (102,302 acres, or 160 square miles) are in the province of Siena; the rest are in the province of Florence.1 There are only 7,200 hectares (17,792 acres, or 28 square miles) of vines registered to produce Chianti Classico,2 with about another three thousand hectares (7,413 acres, or 12 square miles) registered to produce IGP wines (IGP is the initialism of indicazione geografica protetta, or “protected geographical indication,” an EU classification incorporating place designation and quality control standards). Three thousand hectares of olive groves are also registered to produce Chianti Classico DOP olive oil (DOP is the initialism of denominazione di origine protetta, “protected denomination of origin,” a similar EU classification).3 Forest dominates the landscape of Chianti, accounting for about two-thirds of its surface.4 Until the end of World War II, firewood collection was an important activity in Chianti Classico, and hunting is still important there. The trees, mostly oaks, are small, because the soil is so poor and the water in it so scarce. Rather than being concentrated in particular areas, vineyards and olive groves are spread throughout Chianti. The preponderance of vegetation keeps the air clean. Chianti, compared to other famous viticultural areas such as Champagne, Burgundy, and Bordeaux, is in pristine ecological condition.

Vineyards designated to make Chianti Classico wine must be in hilly terrain but not higher than 700 meters (2,297 feet) above sea level. Few vineyards rise above 500 meters (1,640 feet) or reach lower than 250 meters (820 feet) in elevation. The Monti del Chianti, a wall of high hills, delimit Chianti Classico’s eastern flank. The boundary line runs through the highest point of the range, Monte San Michele, which is 892 meters (2,927 feet) high and 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) due east of Panzano. The wall of east-facing mountain slopes from Monte Muro (620 meters, or 2,034 feet, high) at the northern end, east of San Polo in Chianti, to Poggio Macchioni (590 meters, or 1,936 feet, high), northeast of San Gusmè, in the south provides protection from harsh continental weather, particularly cold weather from the east. The Pratomagno Mountains in Arezzo (east of Chianti) loom higher than the Monti del Chianti, sealing Chianti Classico off from the early morning sun. This may be the reason why Chianti Classico winegrowers have historically preferred southern and southwestern exposures to eastern ones. At the southeast corner of Chianti Classico, the upper Arno River Valley opens up somewhat to the east and south, allowing in more morning light. Chianti Classico tends to have wide vistas of the horizon to the south and to the west. The coincidence of light and heat that occurs in late afternoon on plots with a south-southwestern exposure creates riper grapes and therefore more-alcoholic wines, a preference of many wine tasters. That said, variations in weather and factors like being shaded by obstructions such as hills invalidate any hard-and-fast rules about exposure.

As ripening has advanced by several weeks in the past thirty years and as producers have sought vineyard sites that result in lower-alcohol wines, plantings at higher altitudes, from four to five hundred meters (1,312 to 1,640 feet), and with eastern to northern exposures are becoming more desirable. Vittorio Fiore, a consulting enologist and winegrower, said that when he first came to Chianti, thirty years ago, “people told me it was crazy to plant vines at more than 350 meters [1,148 feet].” That elevation was considered too cold to ripen the grapes every year. Gionata Pulignani, the agronomist and head winemaker at Fonterutoli in Castellina, reported that “at the beginning of the 1980s, 350 meters was the best elevation for Sangiovese here. Now five hundred meters is best.” On the other hand, Stefano Porcinai, the consulting enologist for Bibbiano, on the southwestern edge of the zone, noted that alcohol levels in wines are getting so high that less sun is preferred: “Here in the warmer areas of Chianti Classico, north and northeast exposures are now better.” The warmest locations in Chianti Classico are where the elevation is lowest, the San Casciano area and along the western and southern extremities of the zone. The very warmest area may be just north of Monteriggioni, in the southwestern corner, due to its elevation of 250 to 300 meters (820 to 984 feet), its exposure to the southwest, and the warm, humid winds that arrive from the Tyrrhenian Sea off Tuscany’s western coast. Niccolò Brandini Marcolini at Castello di Rencine, which is on a hill that overlooks Monteriggioni, reported that his estate’s harvest is seven to ten weeks earlier than those in the higher-elevation areas nearer to the Monti del Chianti. The water-rich clay soil at Rencine balances the heat of summer, cooling and feeding the vine roots.

While the Monti del Chianti run along the eastern edge of the appellation (from the northwest to the southeast) through Greve, Radda, Gaiole, and Castelnuovo Berardenga, the other outstanding high-elevation feature of Chianti Classico is a ridge that cuts through its width, running west from Badia a Coltibuono (at 628 meters, or 2,060 feet) to Radda (at 530 meters, or 1,739 feet) and Castellina (at 578 meters, or 1,896 feet) and then northwest to Poggio della Macìa Morta (at 632 meters, or 2,073 feet). This divides what Chiantigiani call Chianti Fiorentino on the northern side from Chianti Senese on the southern side. Since the prevailing autumn-to-spring weather systems (including the mistral) come from the northwest, precipitation is higher to the north of this divide, particularly where the wet atmosphere moves up to cooler, higher elevations. Exposures facing the Crete Senesi such as at Castelnuovo Berardenga extend near to the horizon, providing this area with high luminosity.

January and February in Chianti are known for their cold, clear days. In most winters it snows frequently in the hills more than six hundred meters (1,969 feet) in elevation and once or twice at lower elevations. At these lower elevations, where there are vineyards, the snow lingers for several days before melting. Winegrowers hope for cold winter days. When the vines go into full dormancy, it is safest to prune. The eighteenth-century Florentine botanist Saverio Manetti knew his viticultural seasons in Chianti. Writing in 1773 under the pseudonym Giovanni Cosimo Villifranchi, he observed, “In Chianti, the winter is very cold. Thus the custom is to prune the vines in February, which is to say, after the coldest period. To prune early would adversely affect the vine and wound it.”5 Today there are fewer cold winter days than there were in his time. But vines grow better in the spring if they have had the opportunity to be fully dormant during a cold snap in the winter. Such cold weather also reduces or wipes out populations of deleterious microorganisms such as fungi and insect pests (particularly the flying kind). The peasant farmers who tended vines in Chianti for centuries understood the value of winter well. There is an old proverb: “Nell’inverno tramontana, pane e vino alla Toscana” (In the winter, the tramontana [a cold north wind], bread, and wine come to Tuscany).6 In other words, cold winter weather ensures good harvests of grain and grapes.

According to Michael Schmelzer of the Monte Bernardi winery in Panzano, recent warmer winters in Chianti have meant earlier budbreak. In 2014, it happened at the end of February. This increases the possibility of damage by capricious spring frost, such as occurred in 1997 and in 2001. Spring frost kills buds coming to life after winter dormancy, reducing yield and causing uneven ripening.

During the summer in Chianti, the sunny days can extend for weeks without rain. Many streams flow in the winter, only to dry up in the summer. Summer temperatures can rise above 35 degrees Celsius (95 degrees Fahrenheit) during July and August, which are generally the warmest months. Temperatures lower than 4 degrees Celsius (39 degrees Fahrenheit) are not uncommon during the winter.7 The average throughout the year is 13 to 14 degrees Celsius (55 to 57 degrees Fahrenheit).8 Day-to-night temperature variation is greater at higher elevations and on the eastern flank of Chianti Classico, which is the part farthest from the Tyrrhenian Sea. During the growing season, day-to-night variation throughout the zone averages about thirteen degrees Celsius (twenty-three degrees Fahrenheit).9 During the winter, such temperature difference is less. Schmelzer noted that with very few exceptions (one of them being the unusually warm 2003 vintage), day-to-night temperature variation during the preharvest period is significant. This helps skin and pulp to mature at the same rate, allowing for a better balance of wine alcohol to flavor. Specifically, it triggers pigment development in the grape skins and preserves acidity in the pulp, leading to more pigmented, more astringent, and more acidic wines.

A zonation study created for Chianti Classico’s olive oil industry listed a range of nine hundred to one thousand millimeters (twenty-five to thirty-nine inches) for the average annual rainfall from 1993 to 2012.10 Several winegrowers have reported that the weather is subject to more violent changes than in the past. They describe bursts of intense rainfall that they call bombe di acqua (water bombs). Climatically, Chianti can be a chameleon. Some years, such as 2002, can be very wet. Others, like 2003, can be very dry. At Castello di Brolio, only forty millimeters (two inches) were reported for April through August in 2003.11 Typically during these five most important months of the growing period, only 275 millimeters (11 inches) are registered.12

Rainfall is highest during the autumn months, with the most in November and December, an average of 159 and 124 millimeters (6 and 5 inches), respectively, from 1993 through 2012. This had encouraged clonal selection of Sangiovese for earlier-ripening characteristics. During the spring, April regularly has the most rain (ninety-three millimeters, or four inches, on average from 1993 to 2012). The months with the least rainfall are July (twenty-six millimeters, or one inch, on average from 1993 to 2012) and August (thirty-nine millimeters, or two inches, on average from 1993 to 2012).13 Winegrowers appreciate rainstorms of limited duration roughly at the end of June and sometime in August to keep vine maturation from slowing down or stopping because of drought. The significant jump in rainfall in September (to ninety-nine millimeters, or four inches, on average from 1993 to 2012) brings dangers that grape producers must face during the harvest period.14

The combination of water availability and temperature is an important factor in grape maturation. At higher altitudes in Chianti, drought is more likely, because the soils are sandier and rockier and hence more free draining. These soils are poorer in nutrients too. Many experts believe that for hotter vintages, it is better to select wines made from vineyards in Chianti Classico at higher altitudes. They reason that temperatures are cooler there, which is true. However, the Piedmontese agronomist Ruggero Mazzilli, who has been working in Panzano for more than a decade, disagrees. He observed that at higher elevations the coincidence of heat, drought, and low fertility desiccates the grapes more than would be the case at lower elevations, particularly where there are clay-rich soils. At lower elevations, heat causes vine stress. This slows maturation, despite high soil vigor. Ripening is thus delayed until when it is cooler and there is more day-to-night temperature variance.

If drought and high heat occur just before the harvest, as they did in the last half of August 2000, grape maturation halts because of vine stress. Raisining without further ripening can result. However, if there is sustained cool and wet weather during this period, as in the summer of 2002, ripening slows, the grapes swell up with water, and mold attacks and degrades the grape skins. Even if the grapes ripen well in dry conditions but then it rains before the harvest, as was the case in 2012, some botrytis is inevitable. There are magic years when cold summer weather slows the ripening. In 1995, for instance, everyone thought that the grapes would not mature sufficiently. Then came warm and sunny October weather, which pushed them to perfect maturity, with high levels of acidity. Then there are ideal growing seasons for wine quality, such as that of 1997. In that year, spring frost reduced the yield per vine. Perfect summer growing conditions resulted in an early harvest. While analyzing meteorological readings of the 2003 to 2008 vintages, Schmelzer noticed that although Chianti Classico growing seasons overall may be very different from one another, the weather during the last six weeks of vine growth tends to be similar.

High winds are unusual in Chianti Classico. Jurij Fiore at the Poggio Scalette estate in Ruffoli, with a west-facing exposure, says that there is nearly always a light wind, which keeps down mold in the vineyard. While cool, dry air can be a blessing in humid conditions, the ascent of warm, humid winds from low elevations to high ones can produce damaging summer hail. One hot spot for hail is south of Fonterutoli, where hot winds rise quickly from the city of Siena, sharply north and up 250 to 450 meters (820 to 1,476 feet), to Castellina in Chianti. Gaiole and Radda are also more at risk for hail than other areas of Chianti Classico. The part of southwest Chianti Classico near Poggibonsi is affected by warm and humid winds from the Mediterranean, which, by one account, can deposit salt after buds burst, damaging their growth.15 In general, exposures along the western flank of Chianti Classico are strongly affected by weather fronts that arrive from the west. Growers there rarely talk about weather patterns from the south or east. In the interior of the zone, the reports of winegrowers vary so much as to indicate that the chaotic topography of Chianti fragments weather patterns. Black storm clouds can form around its highest points. Where they go from there depends on local wind conditions and the facets of the hills off which they ricochet.

Since the early 1900s, Chianti geologico (geologic Chianti) has been defined by its galestro-, alberese-, and macigno-based soils. These are local names for rock types, described below. The prevailing theories of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries characterized Chianti geologico as deriving from the Eocene epoch. In fact, the geology of its hills is more complex. It is nonetheless easy to identify Chianti geologico, since its rocks have jagged edges, the result of tectonic movement. With the exception of some low spots of more recent sedimentary origin, Chianti geologico predates the formation of the surface northwest of Mercatale Val di Pesa, southwest of Lilliano in Castellina, and along the southern edge of Chianti Classico, the largest area being roughly contained within a triangle whose points are the village of Pianella, Castello di Bossi, and the town of Castelnuovo Berardenga. These areas are mostly from the Pliocene epoch. Their soils are sedimentary. Their stones are round, not sharp. This geologic configuration was one of the primary factors that induced Giovanni Rezoagli to propose new borders for Chianti in his detailed monograph Il Chianti in 1965. His map La regione del Chianti omits the areas of more recent sedimentary origin just mentioned.16 Otherwise, the confines of his Chianti are very similar to those of present-day Chianti Classico.

The concept of Chianti geologico influenced the delimitation of Chianti as a wine zone in the first quarter of the twentieth century. This can be seen in the first statute of the Consorzio del Gallo, from 1924, which describes the soil of Chianti as “geologically formed or derived from galestro, alberese, arenaria [macigno].”17 Since then, the geologic criteria for the delimitation of the Chianti Classico appellation have expanded. According to the current DOCG regulations, the soils of Chianti Classico vineyards must “consist predominantly of sandstone, calcareous marl, clayey schist, sand and pebbles.”18

Macigno is a local Chianti word for arenaria, or sandstone rock. Erosion turns it into sand. There can be patches of foliated arenaria, as in Ruffoli and Lamole. Alberese (from albus, “white” in Latin) is a hardened marl stone that approximates limestone. In contrast, galestro is a highly friable clay schist, perhaps better described as shale. It is petrified clay with fine layers of sand, which allow it to break apart easily along foliations. This foliation occurs with exposure to air. Macigno, galestro, and alberese have always been the key rocks associated with Chianti. Their color varies with their chemical constituents, which are similar to those of the round rocks of the areas with Pliocene soils. Macigno has a low calcium carbonate content, while at the other extreme that of alberese is quite high. Hence, macigno is darker, usually dark gray, brown, or reddish brown, while alberese can be white or a pastel shade.

These stones erode into particles of different sizes, from sand, the largest, through silt to clay, the smallest. Sand is so fast draining that it does a poor job of supplying water and hence nutrients to vine rootlets. As a consequence, wines from sandy soils tend to be pale and lightweight. Vines, particularly infant ones, have a difficult time surviving in sandy soil. It does not support them well, so stakes are needed. Clay, at the opposite extreme, holds water and has the best particle size to allow vine rootlets to take up water and nutrients. Too high a concentration of clay, however, can make soil too dense. This can asphyxiate the roots. Clay soil absorbs water and swells up. When it dries, it cracks, increasing evaporation and allowing too much oxygen to come in contact with the roots. Thus, the surface of clay soil needs to be constantly broken up and smoothed over. It can also be very slippery. Silt is the ugly duckling of the three soil sizes. Viticulturalists rarely have kind words for it. It is neither very fast draining nor very efficient at delivering nutrients to the vine. It also compacts easily under the weight of machines. Soils usually have a mix of all three particle types. Calcium carbonate is a compound that helps soils retain water, but, unlike clay, it never cracks and causes problems. Marl is a lime-rich mud with higher percentages of clay and silt than sand.

The discussion of soil types is very confusing. Soil maps have borders, but in real life there are none in the ground. This is particularly true of Chianti, where soil types can change by the foot. However, broad generalizations can be made. The Monti del Chianti are macigno rock with macigno-based soils, hence sandy. To the west of these mountains, marl mixes with a chaotic jumble of alberese and galestro rocks. In one area, alberese predominates; in another, galestro. The Monte Morello Formation, a sedimentary layer deposited in the Eocene, typifies this mix. It dominates a broad swath of the zone and produces Sangiovese wines with perfume, structure, and longevity (though keep in mind that with current viticultural techniques, fine Sangiovese wine can be made from most of the soils in Chianti Classico).

In the part of San Casciano northwest of Mercatale, in a strip of land north of Sambuca along the Greve River in Tavarnelle, in the area near Pianella in Castelnuovo Berardenga where the Arbia River exits Chianti Classico, and elsewhere along the southern and western borders of Chianti Classico, the soil is principally silty sand. At points where in the Pliocene epoch there were shallow areas of an ancient salt sea, there are now beds of fossil seashells. These fossilized exoskeletons increase the calcium carbonate content of the soil. Where the ancient currents were stronger, as in the Pisignano area just northwest of the town of San Casciano, small round stones are plentiful. The Pliocene soils with a sandy-silty base make lighter wine. At places where the ancient sea currents were more sluggish, the soils are more clayey. There is a particularly clay-rich area just north of Monteriggioni and just east of Poggibonsi. The soil is dark, without stones, and very deep. The wines here tend to be dark and tannic. This was an ancient sea bottom where the currents were too weak to move anything but the finest soil particles. The rounded contours and round stones (where one finds them) give this and other areas with sedimentary soils a gentle feel, which contrasts with that of the jagged contours of the Monti del Chianti and the galestro and alberese rocks that characterize the Monte Morello Formation. In Chianti, one also occasionally comes across pietraforte, a hardened mix of fine sand and high-carbonate cement. Pietraforte bedrock underpins much of Panzano. This hardest and least erodible of all rock in Chianti is used for cornerstones and foundations. It adds no nutrients to soil. It is whitish gray on the outside and dark gray on the inside.

MAPPING CHIANTI CLASSICO

An in-depth, scientific understanding of the terroir of Chianti Classico necessitates a zonation study that breaks up and classifies its surface into units defined by numerous parameters. However, Chianti Classico is such a complex maze of soils, exposures, and elevations that a terroir map easily comprehensible by the typical wine connoisseur cannot be made. There are no fast, easy answers. To date, Edoardo Costantini, a Tuscan pedologist, has completed a scientific zonation study only for Chianti Senese and Castello di Brolio. Such studies are useful not only for large-scale decisions such as where to site vineyards but also for more refined ones such as what type of scion or rootstock to plant, what kind of training system to employ, and whether to install an irrigation system.

The Italian journalist Alessandro Masnaghetti has created tools that help to bridge the chasm between a complex zonation study and a simple subzone map easily accessible to consumers: a vineyard map of Chianti Classico and a series of more detailed vineyard maps for Panzano (the area within Greve) and several individual townships (Radda, Castellina, and Gaiole) in the zone (available at his website, www.enogea.it). Each map identifies the producers who own the vineyards, which are grouped together according to a locality name—that is, the name of a place in the center of the vineyard area, usually the site of a former fattoria. Localities have no borders, but inhabitants and local members of the agricultural trades have referred to them for centuries. On the back of each map, Masnaghetti provides more explication, including the exposure, altitude, and climatic conditions of vineyard areas. He links all of these factors to the typical expression of the wines from each locality. Masnaghetti’s Chianti Classico maps are valuable tools for members of the trade and for highly motivated consumers.

The best near-term solution for consumers and members of the trade who wish to connect Chianti Classico wines to place would be a subzone map, plus subzone names in large letters on the front labels of Chianti Classico wine. However, any system that indicates origin faces a quagmire in defining the borders of subzones. Where should they be? Who is in? Who is out? Arguments circling around these issues are fractious and can end in results that are far from simple and far from relevant.

The only incontestable divisions in Chianti Classico are the legal borders of townships. However, only four of the nine townships that have real estate within the Chianti Classico DOCG are completely within it: Radda, Gaiole, Castellina, and Greve. The other five towns, Castelnuovo Berardenga, San Casciano, Poggibonsi, Barberino, and Tavarnelle, are only partially within the Chianti Classico DOCG. This brings up the issue of how to refer to subzones that consist of only parts of townships. Calling them by the same name as the whole township would misconstrue their legal borders. For this reason, we have created our own names for them (see map 2). Because San Casciano and Castelnuovo Berardenga are mostly in Chianti Classico, we will call the parts of each in Chianti Classico San Casciano Classico and Castelnuovo Berardenga Classico, respectively. Another issue is what to do with those fragments within Chianti Classico that are minor parts of their own townships (namely, Poggibonsi, Barberino, and Tavarnelle) and too small to be subzones at this level. We have consolidated these fragments into a single subzone called San Donato Classico (using the name of San Donato in Poggio, a central village in that area). Creating sub-subzones such as Panzano, Monti within Gaiole, and Lamole/Casole and Ruffoli within Greve would mean creating borders with no legal precedent.

MAP 2

Chianti Classico by Subzone.

Some twenty Panzano-based winegrowers, the Unione Viticoltori di Panzano (UVP), are lobbying to define Panzano as a subzone. Panzano in Chianti is a frazione of Greve in Chianti, but beyond the village it is unclear how this frazione is delimited. There is no official map of a “Greater Panzano” that would include surrounding vineyards. According to Masnaghetti, he created the Panzano map in his “I cru di Enogea” series on his own. The UVP was completely satisfied with his result. In the notes to this map, he explains the rationale for his delimitation of the Panzano viticultural area. For the southwestern border, he selected the border of the Castellina in Chianti township. For the southern border, he used that of the Radda in Chianti township. He extended the northwestern border so as to contain the ridge with the Rignana estate. For the northern, northeastern, and eastern borders, he relied on a delimitation included in a 1912 Panzano frazione proposal to be a township separate from Greve. This request never received national approval. As he indicates in his notes, Masnaghetti made two exceptions to that proposal. On the eastern flank, he did not include the area of Lamole, reasoning that it has a long vinicultural history separate from that of Panzano. Few would disagree. Lamole is a world apart from Panzano. Their growing conditions are very different. The Lamolese Paolo Socci recounts, with a campanilismo (parochial) wink, that the Lamolese used to say, “The wheat is good down there,” implying that Panzano was not famous for its wine. In fact, the richer clay soil of Panzano could support the growth of wheat, while the sand of Lamole cannot. The oro of Panzano’s conca d’oro (“shell of gold” or, with reference to topography, “basin of gold”) refers to the color not of the sun, as is commonly thought, but of wheat. Masnaghetti deviated from the 1912 request in another instance. He stretched his delimitation of Panzano farther to the northwest, up to the Pieve di Sillano, a chapel in the locality of Sillano, so as to include the Vecchie Terre di Montefili estate. His rationalization was that it has had close professional connections with Panzano producers for some thirty years. Although Vecchie Terre di Montifili is on an extension of the ridge on which the village of Panzano is perched and has similar rocks and soil, an argument against its inclusion is that it is no more than 2.5 kilometers (1.6 miles) up the road from the town of Greve. Between them is the hill town of Montefioralle. Greve was born as its marketplace. By contrast, it is difficult to make a strong cultural and historical connection between Vecchie Terre di Montefili and the village of Panzano. Drawing lines in the soil is rarely free of controversy in our political world. Masnaghetti has been courageous to do so. The UVP winegrowers hope that Panzano will be legally recognized as a subzone of Chianti Classico. Drilling down to define and identify place is the important next step for Chianti Classico.