11

THE MEDICI CODE

The naked truth, magnanimous and pure,

Did not exact long sleepless nights of study:

Once having seen her true, sweet loveliness,

The mind, fulfilled, requested nothing more.

“A WOOD OF LOVE (THE GOLDEN AGE),” IN LORENZO DE’ MEDICI: SELECTED POEMS AND PROSE (TRANSLATION BY JOHN THIEM)

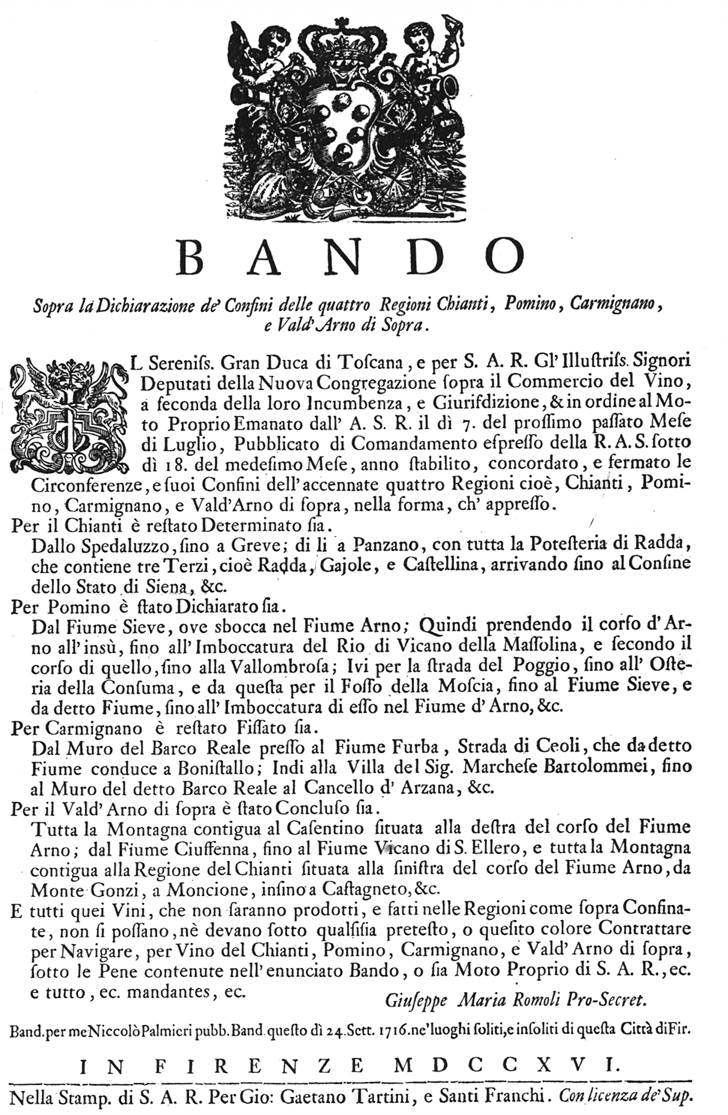

It was May 2014 and we were immersed in our study of Chianti Classico. We had seen Nicolò d’Afflitto, the Tuscan enologist, the previous week in Boston. Now the chief executive of the Frescobaldi wine company, he had invited us to visit him at the estate’s headquarters in Rufina, northeast of Florence. There we could learn more about the work of Vittorio degli Albizzi, the Frescobaldi ancestor who had transformed the family’s Castello di Pomino estate in the nineteenth century. On entering the Pomino winery we were welcomed by D’Afflitto and a giant reproduction of two antique parchments hanging on the wall. Each was crowned with a Baroque version of the Medici six-balled shield. We immediately stopped D’Afflitto to inquire about these images. He explained that they were two bandi issued in 1716 by the Medici grand duke Cosimo III, who had created the world’s first legal appellations of origin with these edicts that regulated and delimited four wine regions in the Florentine State in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany—Chianti, Pomino, Carmignano, and Valdarno di Sopra. The first bando, dated July 18, established the Nuova Congregazione sopra il Commercio del Vino (New commission on the commerce of wine) to oversee the export by sea of wine from the four named regions. The second bando, dated September 24 (see figure 5), delimited their geographic boundaries. It defined “Chianti” to include the principal three towns (“Terzi”) of the Lega del Chianti—Castellina, Radda, and Gaiole—and the area stretching north from them to Panzano, Greve, and the small hamlet perched atop the Greve River Valley, Spedaluzzo. This was a geographic delimitation of Chianti two centuries before the battle over its borders erupted in the early twentieth century.

FIGURE 5

Bando of Cosimo III de’ Medici, the grand duke of Tuscany, dated September 24, 1716, promulgating a delimitation of the wine regions of Chianti, Pomino, Carmignano, and Valdarno di Sopra in the Florentine State. Reproduced pursuant to the GNU Free Documentation License.

We waited until we had returned to our car and were leaving the Frescobaldi estate to confirm that neither of us had seen these two bandi in our previous research. The dal 1716 inscription at the bottom of the Chianti Classico consortium’s logo had taken on new significance. On returning to Boston, we surveyed our library. We double-checked two treatises of the 1770s, one by Saverio Manetti writing as Giovanni Cosimo Villifranchi and the other by Ferdinando Paoletti, that set forth recommendations for Tuscans to boost the export of their wine, including Chianti, and found no reference to either bando. The encyclopedic Dizionario geografico fisico storico della Toscana (Geographic, natural, and historical dictionary of Tuscany), published in 1833, asserts that “no writer, nor any government department, has ever defined what are the limits and the extension of the province of Chianti.”1 Moving to the twentieth century, we were curious whether Torquato Guarducci’s 1909 book on the Chianti wine zone, Il Chianti vinicolo, made any mention of the bandi. Its map of “Il Chianti” (see figure 6) even looks like it could have been drawn directly from the second bando. Not there either. Likewise, there was no mention of either bando in Antonio Casabianca’s exhaustive history of Chianti from 1940, Guida storica del Chianti. Nor were they referenced in Lamberto Paronetto’s Chianti: The Story of Florence and Its Wines, printed in 1967. Then we found a full-page picture of each bando in a 1972 wine guide, Atlante del Chianti Classico, by Enrico Bosi. They were the same images as on Castello di Pomino’s wall, writ small. With glossy photographs of Chianti Classico labels and brief descriptions of each estate and its wines based on a four-star ranking system, this was not exactly a history book. But inserted in the introductory chapter was a mention of the second bando as “an ancient parchment preserved in Brolio castle . . . which specifies the production zone of Chianti wine (corresponding to that of the current ‘classic Chianti’).”2 Yet Gaspero Righini’s Il Chianti Classico, which was also published in 1972 and focuses on the historic, artistic, and literary traditions of the zone, makes no mention of either bando. Raymond Flower’s 1979 book Chianti: The Land, the People and the Wine, which traces the region’s history for more than 250 pages, even more surprisingly makes no such mention. In his postscript, Flower expresses his gratitude to many of the great old families of Florence and Chianti who opened their historical archives to him—including those of the Ricasoli family at Brolio Castle. But still there is no reference to either bando, even after they had appeared in Bosi’s Atlante del Chianti Classico seven years earlier. The plot thickened.

FIGURE 6

Torquato Guarducci, Il Chianti map, from Il Chianti vinicolo: Manuale pel commerciante di vini nella regione del Chianti (San Casciano Val di Pesa: Fratelli Stianti, 1909).

It was only when we looked at books published from the 1990s onward that we saw the 1716 bandi consistently cited as a historical fact, but never with any backstory. Perché (why)? During the decades-long Guerra del Chianti between Chianti Classico and External Chianti, the scholars and journalists of Tuscany chronicled every minute detail of Chianti—its history, geography, culture, and wine. Italians mock their academics for debating “il sesso degli angeli” (the sex of the angels). With the definition of Chianti as a wine zone at the core of the Guerra del Chianti, would not the bando dated September 24, 1716, which declared the geographic boundaries of this region, have been the holy grail for Chianti Classico? Surely the existence of this historic precedent would have proved Chianti Classico’s exclusive right to the Chianti name, whether in 1932, at the time of the ministerial decree legitimizing External Chianti, or in the 1960s, in the lead-up to the creation of the Chianti DOC, which unified Chianti Classico and External Chianti. It appeared as if the two bandi had been lost to history and rediscovered only sometime in the mid-to-late twentieth century. Would not the Chiantigiani have met this rediscovery with great enthusiasm? Would not the scholar or amateur historian who had unearthed it be hailed as a true patriot of Chianti? Yet we could find no story or account of this great historical find. It was time to return to Chianti.

We planned our next trip for October 2014 and, when the time came, packed our bags, mostly with camera equipment, books, and lists of questions. We decided that it was critical to visit Professor Zeffiro Ciuffoletti, a lecturer in history at the University of Florence who has authored dozens of books on Tuscany’s culture and agriculture. He also edited the authoritative volume Storia del vino in Toscana (History of wine in Tuscany), published in 2000. We arranged an appointment at his university office and arrived as waves of students were pouring down the stairs of the Department of History and into the cafés lining Via San Gallo. We found our way to the professor’s office. He greeted us cordially and helped to clear the stack of books from a second chair so we could both sit. After explaining the nature of our research, we proceeded to ask our questions about the two bandi. The professor confirmed our observation that they had been lost with the demise of the Medici principate in the 1730s. The Habsburg-Lorraine grand dukes who rose to power in the mid-to-late eighteenth century had politically and economically transformed (and in the process effectively discredited) the nanny state of the late Medici rulers, instituting a new regime of more liberal laws and regulations. As a result, even the enlightened reforms of the Medici grand dukes gathered dust in the files of the Archivio di Stato di Firenze (ASF, or State archives of Florence). Nonetheless, Professor Ciuffoletti told us that the second bando—the one defining Chianti’s boundaries—was known. It was the first bando—the one establishing the regulatory commission to oversee the export of wines from the named denominations—that had been forgotten, he explained. We were curious about whether any historical research had uncovered contemporaneous references to either bando or shed light on the specific circumstances of their promulgation. We had found a copy of the first bando in a collection of Tuscan laws published in 1806.3 But the second bando was not there. The earliest academic citation of it that we had located was in a compilation of Medici laws first published in 1994.4 The professor assured us that he would be researching this subject in preparation for the events then being organized to celebrate il trecentenario (the three hundredth anniversary) of the bandi in 2016. He confirmed that “we were asking all of the right questions.” But then he cautioned, “As outsiders at the state archives, you will go and get polite smiles but no answers to your questions.” Without the benefit of “drones” (student researchers) and archival insiders, Ciuffoletti told us, we would only be humored in our search for answers. The hunt was on!

Our next meeting was with Niccolò Capponi, a respected historian and the co-owner of the Villa Calcinaia wine estate in Greve in Chianti. In response to our questions about the bandi, he reasoned that the lack of documented research about their provenance was likely due to “the Ponte Vecchio syndrome.” Scholars universally assume that the Ponte Vecchio has been the subject of endless historical research—but in reality only one monograph on it exists. When pressed further about the mystery surrounding the bandi, Capponi provided another explanation, by way of an old Tuscan proverb, “La verità attira la sassata” (Certain truths attract a stoning). Whether or not he was joking, this story became even more intriguing.

Back in Boston, we tracked down a volume by Antonio Saltini titled Vino, conti e contadini: Cinquant’anni di scontri per le denominazioni del Chianti (Wine, counts and peasants: Fifty years of fighting for the Chianti denominations), which tells the story of the Chianti Classico consortium from its founding. In the introduction, Saltini (a noted author on the history of the agrarian sciences) explains that the consortium had engaged him to write an account of its history for its seventy-fifth anniversary in 1999 but then fired him when it deemed his text unacceptably frank. We compared Saltini’s book to the official volume that the consortium published in 1999, Un gallo nero che ha fatto storia (A black rooster that made history), which names Giovanni Brachetti Montorselli as its editor, even though the consortium’s current and former executives credit its former senior officer Girolamo Cavalli instead. It was clear that Saltini’s text was the foundation for the consortium’s book. While Un gallo nero included an image and brief description of the 1716 bandi in its first chapter, Saltini specifically referred to the “granducal bando” as the document that the founders of the consortium had relied on to exclude San Casciano from its official delimitation.5 Could it be that the September 24, 1716 bando was known at the time of the consortium’s founding yet later hidden from view?

We returned to Florence in February 2015 for the consortium’s annual Chianti Classico Collection event. After a full day of tasting at the Stazione Leopoldo, we returned to Hotel Michelangelo, across the street, for a face-to-face meeting with the journalist who seemingly broke the bando story in 1972—Enrico Bosi. He was waiting for us in the lobby. We arranged with the desk clerk for a private conference room in which to talk. Bosi, now retired and living in the countryside of Impruneta south of Florence, is soft spoken and genteel, simpaticissimo in Italian. We reiterated why we were so interested in speaking with him. By our account, he was the first author to publish the existence and image of the 1716 bandi, in his Atlante del Chianti Classico. How did he discover the bandi? Where and when did he find them? How did he beat Tuscany’s vaunted history professors to the scoop? Bosi told us, “The [Chianti Classico] consorzio gave me a copy and told me to publish it in my upcoming book.” He added, “My book came out in 1972, so they would have handed it to me in 1971.” That was it. He did not know where the consortium had found or for how long it had known about the bandi. It was that simple. An unnamed official at the Chianti Classico consortium had fed him the information and told him to print it. No questions asked. Veramente (really)? Enrico was amazed by our curiosity. His earnestness amazed us. We asked about the director of the consortium in the early 1970s. Enrico confirmed that it had been Guglielmo Anzilotti, now retired and living in the hills of Fiesole. He assured us that we could find Anzilotti’s number in the phone book. And so we did.

The next afternoon we were off to visit Professor Italo Moretti at his home in Florence. We walked clear across town along the Arno River. It was as bright and warm as early spring. Navigating the flocks of tourists by the Ponte Vecchio and the Uffizi Gallery, we made our way to Piazza Beccaria and found the professor’s apartment building. Professor Moretti speaks Italian with a quiet and controlled precision. We had met him the previous year at Castello di Volpaia in Radda. He had graciously given us a lecture on the background of Chianti in the context of Tuscan history. We had been studying our history and were hoping that he would be able to answer some of our questions about the bandi. We asked if historians had greeted the 1972 publication of the bandi with interest. Was this an important discovery? Moretti retorted, “What discovery? The bando has always been known.” Then why had it not been publicized earlier? He explained, “Perché dava noia” (Because it was bothersome). But why had historians largely ignored it until now? Just then, we glimpsed a familiar volume on the professor’s bookshelf, La Toscana nell’età di Cosimo III (Tuscany in the age of Cosimo III).6 It was the collection of academic papers presented at a two-day conference on the reign of Cosimo III that was held in Tuscany in 1990. We asked the professor if we could take it down from his shelf and show him what we had found there: only one reference to the bando of July 1716 establishing the Nuova Congregazione, and no reference to the bando of September 1716 delimiting the geographic boundaries of Chianti and the other three named regions. Why would the professional historians who wrote the chapters about Cosimo III’s initiatives to support the Tuscan economy not have discussed this second bando? But the professor had already given us his answer. He added that there is a difference between certain “professionisti” (professionals) and “dilettanti” (dilettantes), concluding, “Salieri was the professional, Mozart the dilettante.” Was this an admonition or encouragement? We left our meeting feeling both perplexed and energized. It was clear by now that there was much more to this story.

In the following days, we met with several of Chianti Classico’s key figures past and present. Ser Lapo Mazzei, who had joined the consortium’s board of directors in 1957 and served as its president from 1974 to 1994, patiently fielded our questions. At almost ninety years old, he still has the dignified bearing of a tribal elder. He spoke with us in proper English, recounting the history of the consortium from its earliest days and talking about the importance of protecting Chianti as a territory. For him, what is most sacred about Chianti is its “civiltà rurale” (rural civilization). In response to our inquiries about when the consortium knew about the bandi, Mazzei said, “I can tell you something.” He paused. “There were udite [murmurings] that certain interesse commerciale [commercial interests] preferred to keep quiet about it.” We listened intently, waiting for him to recount the full story. There was silence. Mazzei cleared his throat and said, “I will need to call Giuseppe [Liberatore, the current director of the Chianti Classico consortium] to speak with him about your questions.” Was this the beginning or the end of our investigation? Time would tell.

Later that week, we drove to the new Marchesi Antinori winery in Bargino. At the entrance gate, we confirmed with the guard that we were there for an appointment with Piero Antinori. This is the vanguard of Chianti Classico. This state-of-the-art winery is not just an iconic architectural statement but also a monument to “Antinori nel Chianti Classico” (Antinori in Chianti Classico). It is planted in San Casciano, the northernmost part of the Chianti Classico appellation—the very area that the founders of the consortium fought to keep out of their zone and that a handful of wine producers (the so-called archtradizionalisti, from Castellina, Radda, and Gaiole) still refer to as not belonging to the real Chianti.

Antinori greeted us with the grace and charm of an ambassador. He met with us privately in a small conference room past the main reception area. Portraits of his father, Niccolò, and of his grandfather and great-uncle, the late nineteenth-century founders of the Marchesi Antinori wine company, hung on the walls. We spoke about his family’s history. In 1385, Giovanni di Piero Antinori became a member of the Arte dei Vinattieri (Wine merchants guild). In the early 1700s, Niccolò Francesco Antinori served as a secretary of state and a state councillor in the court of Cosimo III. We informed Antinori that we were still looking for contemporaneous references to the 1716 bandi and inquired if his family archives might hold the key to finding them. He told us of his growing interest in history. As we explained the anomalies that we had discovered in researching the bandi (especially in the twentieth century), he seemed both intrigued and amused. “Really,” he responded to each of our revelations. “Fascinating . . . this could be a thriller!” “Like The Da Vinci Code,” we jested. Antinori laughed in his gravelly baritone. He picked up one of the small notepads on the conference room table and wrote down the list of documents that we hoped to locate. “I am interested in your research,” he concluded. The next day it was time to pack our bags for the trip home. We were leaving with more books and questions than we had brought with us.

Once back in Boston, we pursued another angle in our research—the English one. We reasoned that because the bando of July 1716 imposed criminal penalties on any merchant or customer buying “false” Chianti, the English merchants based at the free port of Livorno (Leghorn) in Tuscany surely would have taken notice of this law. At the time, Great Britain had an envoy posted at the court of Cosimo III in Florence and a consul posted at Livorno. This was the principal port of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, having been conquered by the Florentines in 1421. Without their own navy or merchant fleet, the Florentines (for all but a brief period in the fifteenth century) relied on the merchant fleets of their Genoese and Venetian rivals. By the seventeenth century, the Medici grand dukes had granted the British free trading privileges at Livorno. This trading post, known as the British Factory, was the foundation of Britain’s growing power in the Mediterranean. At the website of the National Archives of the United Kingdom, we located a file numbered SP 98/23, which contains the correspondence between the consul at Livorno, Christopher Crowe, and the British Home Office during this period. In this file is a letter dated July 24, 1715, from a group of merchants at Livorno, titled “The state and condition of Brittish [sic] trade at this place.” Among its signatories were Crowe and the two partners of the British wine merchant firm Winder and Aikman. Within days, an oversize envelope from the National Archives was on our doorstep. In it was a copy of this letter. The third-to-last paragraph has a clue to the export of Tuscan wine to Britain in the early 1700s. Commenting on “Florence Wine,” the merchants observe that the “continuance of the duties on French wine will be greatly conducive to the increase of this trade.”7 In the War of the Spanish Succession, from 1701 to 1712, the British and the French were enemies, and French wine was the subject of a British embargo. After the war, the British government imposed high tariffs on French wine. The opportunity for “Florence Wine” (which would have included Chianti) to supplant French wine on the English market must have helped to spur the promulgation of the bandi. From 1705 through 1715, Consul Crowe personally had the exclusive right to provision the British fleet in the Mediterranean with wine and olive oil.8 In 1716, he returned home to marry and take up the life of the country gentry. As a result, the British Factory at Livorno was without its consul at the very time when Cosimo III issued the bandi. The chief concern in the correspondence between Livorno and the British Home Office during this period is the appointment of Crowe’s successor. To our surprise and disappointment, we found no mention of either bando in these communications. Why did Crowe have to go and get married then?

It was late March and time for us to return to Italy for Vinitaly. After a four-day stint of tasting Chianti Classico wines at the annual Italian wine fair in Verona, we rented a car and drove south to Tuscany. For the next ten days we lodged in a converted farmhouse in Barberino Val d’Elsa. On our first morning there we were off to launch our archival research at the ASF. We parked near our favorite bookstore in Florence, around the corner from Piazza Libertà, and arranged for yet another shipment of books to Boston. We briskly walked down Viale Giacomo Matteotti toward the ASF (right before Piazza Cesare Beccaria), where we took the elevator up to the third floor. After introducing ourselves to the receptionist, we signed the register and listened to the ground rules for entry into the sala di studio (study room). First, we would need to leave all of our bags, file folders, and pens in a locker. Only pencils and laptops were allowed. Then we would need to show our credentials and register as studiosi (researchers). Through the glass windows of the study room we saw rows of tables with scholars poring over massive volumes of ancient texts propped up on wooden reading stands. Having studied the ASF’s website from Boston, we already had some clues for our research. We began with the inventory series “Controversie di confini e feudali” (Controversies involving borders and fiefdoms). Given our focus on Chianti’s endless border disputes, this seemed like a good place to start. It did not take more than a couple of hours to realize that this would be a steep climb. We were just getting our bearings, we reassured ourselves. We knew that this would be the first of many visits. We had an appointment in the late afternoon with Ser Lapo Mazzei at his home in Florence, so it was time to leave the ASF for now. As it was a Friday afternoon, the traffic was molto intenso. And our GPS was no longer speaking to us in Italian. Suddenly, it was barking directions in Afrikaans! Juggling the Florence street map and the GPS video display, we located our turn, right after Porta Romana. There within the city walls we found an idyllic slice of the Florentine countryside. Olive trees lined the narrow, winding street, and flowering gardens surrounded each country villa.

Mazzei was expecting us. He was elegantly dressed in a suit and tie. He welcomed us into the living room past the library. His spirited black terrier, Brio, curled up next to us on the couch. We began our conversation where we had left off in February. Mazzei began, “I cannot understand why the consorzio did not use the bando in its lotta [fight] against Chianti generico [generic].” He spoke in a quiet but steady and clear voice. “Bettino Ricasoli must have known about the bando,” he stated. Ricasoli was the president of the consortium from 1958 to 1974. “It was known in the 1960s.9 But I do not think that Bettino understood its importance.” We asked Mazzei if he thought that Bettino’s father and predecessor as president from 1947 to 1958, Luigi Ricasoli, had known about the bando even earlier. Mazzei declared, “No, Luigi was a fighter! He would never have sacrificed the opportunity to win back the use of the name Chianti. The bando was not known until the 1960s.” He paused and then said, “Signore Nunzi anche sapeva del bando. Nunzi lo sapeva della importanza storica del bando. Sapeva benissimo!” (Mr. Nunzi also knew about the bando. Nunzi understood the historic importance of the bando. He knew perfectly well!) Gualtiero Armando Nunzi was a member and officer of the consortium’s board of directors from the 1960s until 1997, when he finished his three-year term as its president. Mazzei pulled his mobile phone from his suit pocket and made a call. “Giuseppe, I have two journalists with me who are asking interesting questions. I need to speak with you,” he said, then hung up and told us that he had just left a message for the consortium’s current director, Giuseppe Liberatore. He said that he did not understand why the consortium had locked its historic archives in storage in Prato, outside the Chianti Classico zone. We told him that we would ask about accessing the archives. He responded that he would make a call to support our request if necessary. One of Chianti Classico’s last veteran patriots was himself in search of answers.

Driving back to Chianti, we reconciled what Mazzei had told us with what we had already learned. If Bettino Ricasoli was aware of the September 1716 bando, was it because it had been discovered in his family archives at Brolio Castle (as Bosi’s 1972 book states)? What were Nunzi’s motives? Had there been a powerful faction of commercial interests within the consortium that had believed Chianti Classico would be better off securing the DOC in 1967 conjoined with External Chianti (even if it meant accepting the enlarged delimitation of Chianti established by the 1932 ministerial decree, which its own former president—and renowned lawyer—Gino Sarrocchi had concluded was no longer legally in effect) than fighting on for autonomy based on the bando’s historic precedent? Was the bando kept from the view of the consortium’s full board of directors during the very period (1965–67) when two of its members, Mazzei and Enrico d’Afflitto, were standing up against the incorporation of Chianti Classico into a unified DOC with External Chianti, arguing that “a law not applied is without doubt preferable to a law poorly applied”?10 Who had the means and who had the motivation to quiet history? Perhaps Anzilotti, the director of the Chianti Classico consortium at the time, would be able to fill in the blanks. Or so we hoped.

We located him in the white pages and arranged to meet him on Sunday afternoon. After parking our car on the street outside his home, we rang the bell at his gate to announce our arrival. We expected Anzilotti to be about Mazzei’s age, so when a tall and tan gentleman in bright yellow pants and suede loafers energetically greeted us at the gate, we thought that this must be the son who would bring us to see his ailing father. It was, in fact, Guglielmo Anzilotti. After welcoming us, he immediately asked who had referred us to him. We answered, “Enrico Bosi.” Anzilotti’s wife joined us outside in their garden overlooking the villa-dotted hills of Fiesole. We moved inside to their living room and asked Anzilotti to tell us the story of his work at the consortium.

Bettino Ricasoli hired him to be the consortium’s director in 1963. The prior director, Piero Tesi, had just resigned to become the director of Chianti Classico’s crosstown rival, the Consorzio del Putto. We asked whether Florence’s epic flood of 1966 had damaged the Chianti Classico consortium’s archives. Anzilotti recollected that all of the records were untouched by the floodwaters. His tenure at the consortium had lasted sixteen years, first under Ricasoli and then under Mazzei. Anzilotti regaled us with stories from the 1960s and early 1970s. When he began at the Chianti Classico consortium, he was the third person in its employ. Within a decade, he had organized a high-profile, first-of-its-kind auction of vintage Chianti Classico wines at the Circolo della Stampa (Press club) in Milan, launched a monthly magazine called Notiziario for consortium members, supported the creation of the Associazione Italiana Sommelier (AIS, or Italian sommelier association), and spearheaded the reincarnation of the Lega del Chianti. He also cultivated the support of influential journalists such as Luigi Veronelli. Anzilotti even arranged for the esteemed Tuscan historian Federico Melis to be on the dais at one of the consortium’s high-profile auctions. By his own account, he had almost complete autonomy to promote and run the consortium under Ricasoli. One detail that we had learned from Saltini’s unvarnished history of the consortium was that Anzilotti had come within four votes of being censured by the board of directors in 1967 for having published a newspaper article proclaiming the Chianti Classico consortium’s acceptance of a unified DOC with External Chianti while it was still being hotly debated. But if Anzilotti had had free rein to run the consortium in the early 1960s, who was holding those reins by 1967?

We told him that we had several questions regarding the 1716 bandi. Did he know how Bosi had come to publish an image of them in his 1972 Atlante del Chianti Classico? Anzilotti stated that he had given a copy of the bandi to Bosi. “One day the copy had come into my hands,” he explained. But he did not remember when or how this had happened. As soon as the bandi came to his attention, Anzilotti said, he understood their importance. He even had large copies of them printed and distributed to the consortium’s members for display. He could not remember if that was in the 1960s or early 1970s—but he asserted that the bandi had never entered into the consortium’s deliberations. We observed, “But that would also be true if the bandi had never been disclosed to the consortium’s board.” We then inquired about Il Chianti Classico, published by the consortium in 1974 on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary. Anzilotti had written its detailed historical chapter, which does not mention either bando. We pointed out that this omission was surprising, given that this book appeared two years after Bosi’s. Anzilotti answered, “The reason why I did not publish the bando. I don’t know why. It’s not there?”

We were also curious about Nunzi’s role at the Chianti Classico consortium. He had been the vice president under Ricasoli in the early 1970s and as a member of the board of directors was the consortium’s chief negotiator in the protracted deliberations leading to the creation of the 1967 DOC.11 After building his Bourbon coffee business into Italy’s first national coffee brand, Nunzi sold it at its peak and founded the Castelli del Grevepesa cooperative in 1965. Anzilotti recounted how at the consortium he and Nunzi had fought “the big fight together.” We asked if Nunzi could have been the source of the bandi. Anzilotti paused and then answered, “Può darsi” (Could be). (Può darsi was often the response to our questions regarding the bandi.) We learned that in the 1970s, Nunzi had also founded and become the president of Con.Vi.To, a consortium of Tuscan wine cooperatives (presumably with a vested interest in External Chianti). Mazzei’s 1960s-era epithet for the larger commercial interests, Gallo Grigio (Gray rooster), came to mind. At least fifty shades of gray!

We left our meeting with Anzilotti puzzled. We still did not understand why the consortium’s 1974 book honoring its golden anniversary omitted any reference to the bandi. It made no sense. The consortium must have had an interest in having the bandi disclosed by the early 1970s but not being associated with it. We were also still looking for who had rediscovered the 1716 bandi and when. Had any of the founders of the Consorzio del Gallo known about it? We made a request to Liberatore to review the verbali (minutes) of the board of directors’ meetings from 1924 to 1932 and any maps of the appellation from that period. He responded that the consortium’s archival documents were securely stored in Prato. We never did get the keys to that castle.

We continued our hunt for historical evidence of the 1716 bandi as well and found our first real lead in a 2003 volume of a journal titled Ager Clantius. An archivist at the Archivio di Stato di Siena (ASS, or State archives of Siena) had discovered a contemporaneous record of the first bando.12 Eight days prior to its issuance by Cosimo III on July 18, 1716, the Balìa, or ruling commission, of the Sienese State (subject to the authority of the grand duke of Tuscany) was assessing its impact on Siena’s wine producers. A Sienese nobleman named Giulio Del Taia had written a letter of warning to the Balìa immediately after Cosimo III had signed a motu proprio (royal decree) on July 7 appointing the Nuova Congregazione to oversee the commerce of wine. Del Taia was not a disinterested observer. He was among the biggest Chianti wine producers and exporters in the state of Siena. His estates were in localities around the township of Castelnuovo Berardenga, including Arceno, San Gusmè, Villa a Sesta, and San Felice. At the same time, his marriage into the prominent Florentine family the Serristoris put him into personal contact with Cosimo III. Del Taia’s missive reads like it could have been written by an influential Castelnuovo Berardenga wine producer just prior to the founding of the Consorzio del Gallo in 1924. He notified the nine members of the Balìa that the Nuova Congregazione would imminently issue a law delimiting the borders of Chianti, Pomino, Carmignano, and Valdarno di Sopra and correctly predicted that it would exclude any areas within the Sienese State from the Chianti zone.

The next day we headed to the ASS to see if we could read Del Taia’s letter and the minutes of the Balìa’s deliberations firsthand. Located in a Renaissance-era palace off Piazza del Campo, the ASS is intimate compared with its Florentine counterpart. After climbing the stairs to the third floor, we walked down a long hallway lined with historic maps and prints depicting Siena. On finding the sala di consultazione (reference room), we completed the request forms for the Balìa minutes and the Del Taia family archives. Within fifteen minutes the archivist brought us to a back storage room where she had collected several bulging cardboard files and volumes for our retrieval. Cloth ties (some in bows and others in knots) held each twenty-to-twenty-five-centimeter-deep (eight-to-ten-inch-deep) file together. We brought them one by one to the reference room. Rows of wooden desks faced a tall window, through which sunlight streamed, bathing the room. With pencil and paper in hand we leafed through the thin pages inside each file. There were documents detailing the production of various Del Taia estates stretching from the Maremma to Castelnuovo Berardenga. We turned our attention to the red-leather-bound volume of the Balìa minutes titled Deliberazioni dell’anno 1715 fino al 1717 (Deliberations of the year 1715 to 1717).

There in black and white in the entry for Friday, July 10, 1716, we found the margin annotation “Vino del Chianti Sanese [sic] non può vendersi per la navigazione” (Sienese Chianti wine may not be sold for maritime export)—for the Balìa’s deliberations only three days after Cosimo III’s royal decree! The minutes include the full text of Del Taia’s letter to the Balìa. With a preternatural understanding of the importance of origin, particularly in export markets, he wrote, “Losing the Chianti name would result in the interested parties’ loss of credit for their wine, as often the perfect quality of the wines themselves does not suffice: in foreign nations great credit is given to the region of origin of the wine.”13 He estimated that Siena’s wine producers, including noble families such as the Piccolomini and Sergardi, together with “many people in the countryside,” exported three thousand barili (136,740 liters) of wine per year “under the Chianti name.”14 He had learned that the Nuova Congregazione would be willing to allow Siena’s producers to use the name Sienese Chianti provided that they subjected themselves to its full legal jurisdiction. He urged Siena’s ruling officials to find a solution to the impending threat to its winegrowers, “for once the above-mentioned congregation decides the borders of Chianti, which will immediately be approved by His Royal Highness [Cosimo III], we will not have time to find a remedy to the damages that will result to our nation.”15 The minutes of the Balìa’s meeting also include the text of the petition that Del Taia submitted directly to Cosimo III to protest the anticipated exclusion of Siena from the Chianti denomination. He made an impassioned argument that the “Region of the true Chianti” included the parts of the State of Siena that were well known for making excellent Chianti wine that was as capable of withstanding the rigors of navigation as any other wine of Tuscany, having been born in “rocky and lean soil.”16

The Balìa reconvened on August 7 to deliberate further about the Florentine Congregazione’s stipulations for recognizing a Sienese Chianti. In the end, its members rejected the jurisdictional conditions and decided not to make any further appeals on behalf of Siena’s Chianti producers. But what happened after the Congregazione published the bando with the delimitation of Chianti, which, as Del Taia had anticipated, extended per its terms only as far south as the “Border of the State of Siena”? We quickly turned the pages to see if there was any mention of that second bando in these minutes. There had been a meeting of the Balìa on September 25, the day after the second bando was issued. But there was no reference to this bando. However, there among the names of the attendees was Giulio Del Taia. Was he there to report on the new bando? The record went cold. But in our review of the Del Taia family archives at the ASS, we learned that he had purchased three farms between San Gusmè and Arceno from 1715 to 1730. Was he expanding his landholdings in Sienese Chianti because the bando had been revised to include this part of Siena, or had it remained on the books without ever being enforced? In July 1716, Del Taia had been a witness to history. He understood what was at stake for himself and the other winegrowers of Sienese Chianti. And he stood ready to fight, appealing directly to Cosimo III and Siena’s Balìa, “not only for self-interest, but also for the common good.”17 He was an early patriot of Chianti Senese. Remarkably, his descendant Giulio Grisaldi Del Taja became one of the founders of the Consorzio del Gallo in 1924.

After these initial adventures in the state archives of Florence and Siena, we returned home to Boston. There was much work still to do. Who within Cosimo III’s court was responsible for the creation of the bandi and the delimitation of Chianti? Where did the idea of a legal appellation of origin germinate? History had all but forgotten the period of the Medici grand dukes. At the center of Cosimo’s court was a brilliant Renaissance man named Lorenzo Magalotti. He had traveled in Europe with the young Cosimo in 1668–69. In 1692–93, Cosimo gave him a high-profile commission: “to study the feasibility of putting Tuscan wines in the place of French wines on the English market.”18 Perhaps Cosimo had entrusted him with this engagement because together they had personally witnessed the prestige conferred upon the expensive claret wines of the Bordeaux châteaux in London almost twenty-five years earlier. By 1692, England and France were enmeshed in the Nine Years’ War, on opposite sides, and the British embargoed French wine from 1690 to 1696, creating an opening for Tuscan wines on the English market. Did Magalotti ever finish his commission? Further hunting revealed two citations in the early eighteenth century of an unedited treatise attributed to Magalotti, titled Trattato per regolare il commercio del vino (Treatise on the regulation of the commerce of wine).19 Did it provide the regulatory framework for the first bando and the outline of the delimitation of Chianti in the second bando? After checking with the ASF and the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze (National Central Library of Florence), we inquired with the Riccardiana, Marucelliana, and Laurentian Libraries in Florence about the existence of this treatise. None of them could locate it in their archives. Our search for answers continued.

We returned to Chianti in May 2015. It was our last trip before finishing this tale. One day at the ASF turned into two, but not without bearing some interesting leads. Listed in the inventory of the Magalotti archives was a file titled “Riflessioni sulla navigazione dei nostri vini per l’Inghilterra” (Reflections on the shipping of our wines for England). We immediately filled out a request form. Within an hour, after depositing our passports as collateral, we retrieved file #175(d) from the documents request room. Like those in the ASS, it was bound in a thick cardboard folder secured with cloth ties. We located an empty table in the study room and began turning the fragile sheets of paper. Each page was divided down the middle. Magalotti wrote his draft text on the right-hand side, leaving the left for his annotations and corrections. Seeing the lines of crossed-out text and inserted annotations, we imagined Magalotti (with ink quill in hand) feverishly putting his thoughts to paper. It was like deciphering archaic code. The antiquated penmanship and the bleeding of ink through the translucent paper made for a challenge. These surely must have been Magalotti’s notes and draft for the Trattato commissioned by Cosimo III. In assessing the English palate, he wrote, “It is necessary to remember that the English love big wines, and to ensure from where the Chianti, Valdarni, and similar ones will be the most suitable for this commerce.” Here it was right before our eyes—the conception of the bandi! Magalotti understood that for Tuscany’s highest-quality wines, such as Chianti, to compete on the English market, it was imperative to ensure their place of origin.

Later in his margin notes, he wrote that “Chianti, Carmignano, Artimino, and Valdarno” were the Tuscan regions whose quality wines were most often counterfeited. He explained that it would be necessary to put in place a mechanism to “prevent fraud, which could discredit such commerce.” To that end, he observed that it would be “highly advisable to deputize trustworthy people to oversee the wines to be shipped [overseas].” While these draft pages are not dated, it was clear that we were reading Magalotti’s work papers for the special commission that Cosimo III gave him in 1692 or 1693 (the same year when Cosimo reappointed him as a state councillor). Magalotti had created the blueprint for the 1716 bandi as early as the mid-1690s. How did he come to these observations?

During their trip to England in 1669, he and Cosimo had spoken with a respected Tuscan merchant named Antonio Antinori, whom they met on a ship in Plymouth.20 Could it be that Antinori had experience in exporting Tuscan wine to England and was the source of some of Magalotti’s ideas on this subject two decades later? In addition to serving as a senator and as Cosimo III’s treasury minister in the late 1690s and early 1700s, Antinori (along with members of the prominent Corsini, Capponi, Gondi, and Ginori families) was appointed by Cosimo in January 1712 to the Nuova Congregazione del Commercio (New commission on commerce), charged with improving the trade of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.21 Could this have been the same Nuova Congregazione to which the 1716 bandi refer? To date, the ASF has been unable to locate the motu proprio issued by Cosimo on July 7 of that year, which created the Nuova Congregazione on the commerce of wine, leaving unanswered the question of its composition.

Our time in Chianti was growing short. Meanwhile, we were scheduled to finish our second week of tasting at the Chianti Classico consortium’s headquarters. Once housed (fittingly enough) in Niccolò Machiavelli’s residence-in-exile in Sant’Andrea in Percussina in San Casciano, it is now in an industrial park in Sambuca, also in San Casciano. We remembered that Anzilotti had mentioned the consortium’s monthly newsletter, the Notiziario. We had a hunch that it would make for interesting reading. So we asked an official at the consortium if it maintained copies of this publication. She took us to the storage room to show us the binders of the giornale, as the consortium refers to it. We carried them to the glass-walled tasting room on the main floor where we were encamped along with the hundreds of Chianti Classico bottles made available for our tasting that week. Intermingled with detailed articles chronicling the latest developments in the consortium’s long march to secure the DOCG were in-depth pieces on enology, viticulture, history, and culture. Anzilotti typically wrote the cover story and appeared to be the editor of the Notiziario. While Bill methodically tasted through the wines blind, I quietly immersed myself in the world of the consortium from 1968 to 1974. In the June 1971 issue was a story about the historical research of a handful of fourth and fifth graders from the Castellina in Chianti elementary school. Buried inside was a reference to a document that had been found in the sotterranei (underground cellars) of Brolio Castle. It was described as the 1716 disciplinare that Cosimo III had established to regulate the production and declaration of wine. The existence of Cosimo III’s 1716 bandi was finally revealed. Now, that is news!

So there it was. During the same period when Anzilotti (by his own admission) had given a copy of the bandi to Bosi, the discovery was quietly revealed to the members of the consortium in the pages of the Notiziario. The story read and was illustrated like a fairy tale. By all appearances, the consortium had wanted to disseminate news of the bandi in a way that made it appear as if they were always known. It was as if there was a long-lost counterpart to Leonardo da Vinci’s colored topographical map Val di Chiana, the mythical Val di Chianti map, and on rediscovering it, the consortium, instead of arranging for this priceless find to be displayed (to great fanfare) on the Uffizi Gallery’s walls, had discreetly mentioned it in its monthly newsletter and subsequently handed it to a local gallery owner to include in his upcoming catalog. And no questions were asked.

While perusing the consortium’s small library of books, we also located a bibliography of Chianti. In it we identified another document of interest, an inventory of the Ricasoli family archives at Brolio Castle prepared by Sergio Camerani in 1942. Surely it must list the July or September 1716 bando, given the provenance that the Notiziario and Bosi’s book claim for each. The next day we headed back to the ASF, to which, we learned, the Ricasoli family had donated their archival documents in four installments from 1975 to 1982. We located the volume with the Ricasoli inventory, titled Pergamene (Parchments). In it was a catalog of 475 parchments from Brolio Castle dating from 1317 to 1807. But this chronological list skipped from 1705 to 1717. No bando from 1716! How could this be? The inventory was a mimeograph of a typed list without any indication of authorship. By cross-checking an online database of inventoried private archives, we discovered that the 1942 Camerani inventory of Brolio Castle’s archives also included exactly 475 parchments and ended in 1807.22 It appeared that the ASF’s inventory of Brolio Castle’s “parchments” was indeed Camerani’s inventory. But how was the September 1716 bando not included yet later discovered in those same archives when they were donated to the ASF beginning in 1975 (following Luigi Ricasoli’s death in 1974)?23 There were no more witnesses to history for us to interview. But our questions regarding the provenance of the 1716 bandi remained.

Before leaving the ASF that morning, we checked one more lead. We located the volume cataloging the Medici “leggi e bandi” (laws and bandi) in the ASF archives for the eighteenth century, then turned to 1716. There were entries for both the July 18 and the September 24 bandi and an indication that the ASF had three copies of each. An announcement of a new law like a bando would have been printed by the hundreds and, per the typical declaration of the town crier named at the bottom of the document, “posted in all of the usual places.” Reading through the volume, we came upon a bando dated November 1716. We requested a copy of it from the assistant in the study room. It turned out to be a one-paragraph document titled “Proroga per la portata del vino del corrente anno 1716 delle quattro regioni Chianti, Pomino, Carmingnano, e Vald’ Arno di Sopra” (Extension for the declaration of wine for the current year 1716 of the four wine regions Chianti, Pomino, Carmingnano, and Valdarno di Sopra). We had never heard of this third bando. It was signed by the same official of the Nuova Congregazione, Giuseppe Maria Romoli, who had signed the bando of September 24. This third bando extended the filing date for 1716 from the end of November to December for the portata (declaration) of annual wine production that the July 1716 bando stipulated. The reason given was “poor weather for maturing the grapes, and the more than usual delay of the harvest for the past season: making it unlikely that the declarations will be able to be accomplished, as required, from the collection of the wine, within the current month of November.” So as it turned out, 1716 was a difficult vintage, though an excellent one for wine law.

These 1716 bandi then seem to disappear. Already by 1729, a merchant company founded by Bartolomeo Bandinelli of Villa di Geggiano near Pianella (just to the north of Siena) was exporting flasks and half flasks of “vino di Chianti” (wine of Chianti) to London via the port of Livorno. Based on the delimitation of Chianti in the September 24 bando, this villa (a present-day Chianti Classico estate) was not allowed to export its wine as “vino di Chianti.” Yet like Giulio Del Taia, Bandinelli and his partners did not appear to be impacted adversely by the 1716 bandi. Did the Nuova Congregazione ever enforce them? The market conditions in Great Britain looked favorable for the wines of Tuscany during this period. In 1728, Great Britain passed a law that included a clause to “prevent the Importation of Wines in Flasks, Bottles, and small Casks, except Wines of the Growth of the Dominions of the Great Duke of Tuscany.”24 This exception should have aided the Grand Duchy’s enforcement of the 1716 bandi, which were aimed at increasing Tuscany’s export of Chianti to Great Britain.

The winds of change, however, had already begun to blow through Tuscany in 1713, on the death of Cosimo III’s first son and heir, Ferdinando. From then until his own death in 1723, Cosimo had bigger problems than wine on his royal hands. He (and his secretary of state, Niccolò Francesco Antinori) waged a diplomatic and legal campaign to preserve control of the Grand Duchy for the Medici family. The greater state actors of Europe made their own plans, and in 1737, the last Medici male heir died and the centuries-long reign of the family (and its laws) came to an end. Still, in creating the first legal appellations of origin for wine, Cosimo III made history in 1716. Undoubtedly, there are original documents relating to the promulgation and enforcement of these bandi buried in Florence’s multiple public and private archives. But like a grand cypress falling in a far-off forest, this groundbreaking legal code seemingly made no sound. For Chianti, the September 24, 1716, bando became its secret code.

For all of the mystery surrounding “the Medici code,” the text of each bando provides clues to understanding its genesis and disappearance. Cosimo III issued the one dated July 18, 1716, as a proclamation. It is titled “Bando sopra il commercio del vino” (Law on the commerce of wine).25 Its preamble sets forth its purpose: Cosimo III was appointing the Nuova Congregazione to ensure that the wines from the geographic regioni (regions) of Chianti and the three other named zones produced for overseas export were “fit for shipment with the maximum guarantee of their quality” and to do everything “to prevent fraud.” This statement of intent has the letter and spirit of an appellation of origin law. Pursuant to this bando, the producers of Chianti and the other three regioni were required to file a portata every year by the end of November disclosing the amount of wine produced in their cellars, whether directly or by their tenant farmers, from vines on the hillsides and from those on the plains, and made puro (pure) versus with the governo method. In addition, they were subject to inspections by the Congregazione and obligated to verify the quantities of wine sold directly at their cellars and for shipping overseas. The annual declarations had to be filed with both the Congregazione and the podestà of the town where the producer was located (where they would be available for public inspection at no cost). The Congregazione was charged with publishing a summary of these portate (the plural of portata) by producer name every year. The provision that the content of the producer declarations be publicly available and the stipulation that each producer would remain free to make its own commercial decisions about when and how to sell its wine (whether domestically or overseas) reflect a level of transparency and legislative restraint that was itself ahead of its time. Beyond regulating producers in Chianti, this bando stipulated that any merchant buying Chianti for export had to file a declaration with the Congregazione within fifteen days of the purchase, specifying the name of the seller and the sale price of the wine. Each producer was free to file a declaration of such sales with the Congregazione, to encourage compliance by purchasers. In effect, the system of disclosure requirements that the July 1716 bando established provided a mechanism for traceability—an essential component of quality control. The law even imposed criminal sanctions on merchants, coachmen, shippers, and foreign buyers who were trafficking in counterfeit Chianti. Punishment would include disgorgement of the wine or its monetary value. This bando had teeth!

The Nuova Congregazione issued the second bando, on September 24, 1716, which is titled “Bando sopra la dichiarazione de’ confini delle quattro regioni Chianti, Pomino, Carmignano, e Vald’ Arno di Sopra” (Law on the declaration of the borders of the four regions Chianti, Pomino, Carmignano, and Valdarno di Sopra).26 To implement the regulatory mechanism established by the July 18 bando, it was critical for the Congregazione to define the boundaries of Chianti and the other three named wine regions. Del Taia had advised Siena’s Balìa that this would be among the first decisions of the newly appointed Congregazione in Florence. It took a little more than two months to settle, just in time for the anticipated harvest of 1716. Were the boundaries of Chianti a subject of intense debate among Florentine producers? Could that be the reason why it took Cosimo III almost twenty-five years to turn Magalotti’s recommendations into law? Did any influential Florentine landowners with vines in San Casciano or beyond petition him to be included in the Chianti wine region, in the same manner as the Sienese Del Taia had? Alas, we have the words of only the September 24 bando.

Its preamble states that the deputies of the Nuova Congregazione, acting within their full authority and jurisdiction regarding the commerce of wine, have established the circonferenze (perimeters) and confini (borders) of the regions of Chianti, Pomino, Carmignano, and Valdarno di Sopra. The closing paragraph declares that any wines that are not “born and made in the regions as delimited above” will not be allowed to be exported as wines from these regions. Between these provisions are four paragraphs, each delimiting one of the regions. The wine region of Chianti is defined as “Dallo Spedaluzzo, fino a Greve; di li a Panzano, con tutta la Potesteria di Radda, che contiene tre Terzi, cioè Radda, Gajole, e Castellina, arrivando fino al Confine dello Stato di Siena” (from Spedaluzzo, until Greve; from there to Panzano, with all of the territory under the jurisdiction of Radda, which includes the three towns [of Chianti], that is Radda, Gaiole, and Castellina, coming up to the border of the State of Siena). This is a list of hamlets and townships from north to south. The delimitations of Pomino, Carmignano, and Valdarno di Sopra, by contrast, make multiple references to specific rivers, streams, mountains, roads, villas, and taverns. In naming exclusively the hamlets and townships of Chianti, the Congregazione specifically defined only its northern and southern boundaries—not its western and eastern ones. However, the western border of the Valdarno di Sopra region, which runs north-south along the Arno River (parallel to the Monti del Chianti), would have been understood as the natural demarcation for Chianti’s eastern border.

But where was its western border? For a region like Chianti, which is marked by the Pesa, Greve, and Arbia Rivers and their eponymous valleys, the omission of any references to such geographical features is curious. Given the descriptions of the other three regions, this could not have been simply a drafting oversight. The natural boundary of Chianti’s western border would have been either the Greve or the Pesa River, to the west of Greve and Panzano, respectively. Could it be that certain powerful Florentine families with estates in the southern part of San Casciano (such as the Corsini or the Antinori), to the west of Greve, had voiced their objections to Cosimo III and his Nuova Congregazione? So instead of specifying a western border, and thereby perhaps expressly excluding San Casciano from the delimitation of Chianti, the Congregazione was discreetly silent on this question. At the same time, its delimitation of Chianti (which reads like the blueprint for Torquato Guarducci’s Il Chianti map from almost two hundred years later, including the prominent reference to the tiny hamlet of Spedaluzzo) could be construed as a triangle with Spedaluzzo as its northern point, the line from Greve to Panzano and then to Castellina as its left side, from Castellina to Gaiole as its bottom side, and the Monti del Chianti north to Monte San Michele and the hills up to Spedaluzzo as its right side.27 Unfortunately, much like the founders of the Consorzio del Gallo in 1924, the deputies of the Nuova Congregazione in 1716 did not supplement their delimitation with a map. Nonetheless, they painted a fascinating picture!

Cosimo III’s 1716 bandi deserve to be celebrated as historic achievements by Chianti Classico, Tuscany, and Italy. They represent the first legal appellations of origin in the long story of wine. Cosimo, the penultimate Medici ruler of Florence and most of Tuscany, aimed to have the quality wines of Chianti and the other prized regions of his Florentine domain compete with the wines of France on the English market. In the twentieth century, Chianti Classico could have used the September 24 bando to defeat, once and for all, the claims of External Chianti to the name and identity of Chianti. In our attempts to solve the mystery of “the Medici code,” this much has become clear. The so-called Guerra del Chianti between Chianti Classico and External Chianti masked a guerra del Chianti inside Chianti Classico—a quiet campaign waged by powerful merchant-producers against the authentic winegrowers of Chianti. Certain influential members of the Chianti Classico consortium knew of the existence and significance of the September 24 bando as early as the 1960s. For their own commercial priorities, they kept it hidden from view until the early 1970s. From 1963 to 1967, the years when Italian Law 930 and the Chianti DOC were finalized, enshrining the Fascist-era ministerial decree of 1932 that extended the Chianti denomination to External Chianti, these merchant-producers chose to suppress a crucial precedent for Chianti Classico’s historic and legal claim to the name Chianti. And their standard-bearers and scholars stood silent. This was a betrayal of history and of the rightful patrimony of Chianti’s winegrowers past, present, and future.28 Rather than the prostrate Bacchus at the center of Vasari’s painting of the Ager Clantius upstairs in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio, it is Michelangelo’s David just outside the entrance to the palace that should be the model for Chianti Classico and its winegrowers.29 Depicted in the decisive moment before confronting Goliath, David stands tall, resolute, and armed to vanquish the mighty Philistine—with his slingshot and rock in hand. The winegrowers of Chianti Classico owe their land and its history no less courage and honor in the fight for the true Chianti.