115

LIE #5

Thomas Jefferson Advocated a Secular Public Square through the Separation of Church and State

Many of the lies about Jefferson, from education to the Bible, have been made to support one key overarching premise: Jefferson was secular and therefore his overall goal was a public sphere devoid of religion and from which religious expressions had been expunged. Typical of this oft-repeated charge is the claim that “Jefferson’s Presidential administration was probably the most purely secular this country has ever had.”1

But before determining whether Jefferson really was a secularist, it is important to define that term—a term that did not exist until modern times. By definition, secularist means:

• holding a system of political or social philosophy that rejects all forms of religious faith and worship

• embracing the view that public education and other matters of civil policy should be conducted without the introduction of a religious element2

• having indifference to, or a rejection or exclusion of, religion and religious considerations3

• believing that religious considerations should be excluded from civil affairs4

116

From what has thus far been presented from Jefferson’s own writings and actions, it is indisputable that he was not a secularist by the first three definitions. And this chapter will demonstrate that Jefferson definitely did not embrace the fourth point, that religious considerations should be excluded from civil affairs.

But for those who maintain otherwise, since they already believe that he was a secularist it is logical to further assert that Jefferson was also the father of the modern separation of church and state doctrine. In fact, they actually believe that Jefferson personally placed the separation of church and state into the First Amendment of the Constitution in order to secure public secularism. Consequently, these modern proponents claim:

Jefferson can probably best be considered the founding father of separation of church and state.5

Jefferson . . . is responsible for the precursor to the First Amendment that is almost universally interpreted as the constitutional justification for the separation of church and state.6

[T]he First Amendment was Jefferson’s top priority.7

Thomas Jefferson—the Father of the First Amendment.8

Others similarly claim that Jefferson is responsible for the First Amendment,9 and many modern courts also espouse this position—a trend that began in 1947 when the US Supreme Court asserted:

This Court has previously recognized that the provisions of the First Amendment, in the drafting and adoption of which . . . Jefferson played such [a] leading role.10

117

In subsequent cases the Court even described Jefferson was indeed “the architect of the First Amendment.”11 So firmly does the Court believe this that, in the six decades following its 1947 announcement, in every case addressing the removal of religious expressions from the public square it used Jefferson either directly or indirectly as its authority.12

Interestingly, however, the current heavy reliance on Jefferson as the primary constitutional voice on religion and the First Amendment is a modern phenomenon not a historic practice.13 Why? Because previous generations knew American history well enough to know better than to invoke Jefferson in such a manner.

Two centuries ago a Jefferson supporter penned a work foreshadowing modern claims by declaring Jefferson to be a leading constitutional influence. When Jefferson read that claim, he promptly instructed the author to correct that mistake, telling him:

One passage in the paper you enclosed me must be corrected. It is the following, “and all say it was yourself more than any other individual, that planned and established it,” i.e., the Constitution.14

What did Jefferson see wrong in stating the very claim repeated today? He bluntly explained:

I was in Europe when the Constitution was planned and never saw it till after it was established.15

A simple fact unknown or ignored by many of today’s writers and scholars is that Jefferson did not participate in framing the Constitution. He was not even in America when it was framed; so how could he be considered a primary influence on it? And he was also out of the country when the First Amendment and Bill of Rights were framed. As he openly acknowledged:

118

On receiving [the Constitution while in France], I wrote strongly to Mr. Madison, urging the want of provision [lack of provision] for the freedom of religion, freedom of the press, trial by jury, habeas corpus, the substitution of militia for a standing army, and an express reservation to the States of all rights not specifically granted to the Union. . . . This is all the hand I had in what related to the Constitution.16 (emphasis added)

Jefferson’s only role with the Constitution was to broadly call for a general Bill of Rights. While this is no insignificant thing, it was the same action taken by dozens of other Founders. So how can Jefferson be the father of the First Amendment if he never saw it until months after it was finished? Significantly, there were fifty-five individuals who framed the Constitution at the Constitutional Convention and ninety in the first federal Congress who framed the Bill of Rights; Jefferson was among neither group.

So why have so many courts and modern writers made him the singular go-to expert on religion clauses from documents in which he had no direct involvement? Why has he been given a position of “expert” that he himself properly refused? It is because he penned a letter containing the eight-word phrase “a wall of separation between church and state.” Courts and modern scholars have found that simple phrase, when divorced from its context, useful in providing the appearance of historical approval for their own efforts to secularize the public square.

Historically speaking, Jefferson was a latecomer to the separation phrase. The famous metaphor so often attributed to him was introduced in the 1500s by prominent ministers in England. And throughout the 1600s it was carried to America by Bible-oriented colonists who planted it deeply in the thinking of Americans, all long before Jefferson ever repeated it. So what was the historic origin of that now-famous phrase?

119

Jefferson was familiar with the writings of the Reverends John Wise, Joseph Priestly, and many others who divided the history of Christianity into three periods. 17 In Peroid I (called the Age of Purity), the followers of Jesus did just as He had taught them and retained Bible teaching uncorrupted. In Period II (the Age of Corruption), State leaders declared themselves also to be the Church leaders and seized control of the Church, assimilating it into the State and thus merging the two previously separate institutions into one. But in Period III (the Age of Reformation), Bible-centered leaders began loudly calling for reinstating the Bible-ordained separation between the two entities.

In the Scriptures, God had placed Moses over civil affairs and Aaron over spiritual ones. The nation was one, but the jurisdictions were two with separate leaders over each. In 2 Chronicles 26, when King Uzziah attempted to assume the duties of both State and Church, God Himself weighed in; He sovereignly and instantly struck down Uzziah, thus reaffirming the separation He had placed between the two institutions.

Period III Christian ministers understood these Biblical precedents and urged a return to the original model. As early Methodist bishop Charles Galloway affirmed:

The miter and the crown should never encircle the same brow. The crozier and the scepter should never be wielded by the same hand.18

Of the four items specifically mentioned—the miter, crown, crozier, and scepter—two reference the Church and two the State. Concerning the Church, the miter was the headgear worn by the high priest in Jewish times (see Exodus 28:3–4, 35–37) and later by popes, cardinals, and bishops. The crozier was the shepherd’s crook carried by Church officials during special ceremonies. Pertaining to the State, the crown was the symbol of authority placed upon the heads of kings, and the scepter was held in their hand as an emblem of their extensive power (see the book of Esther). Therefore, the metaphor that “the miter and the crown should never encircle the same brow” meant that the same person should not be the head of the Church and the head of the State. Galloway’s declaration that “the crozier and the scepter should never be wielded by the same hand” meant that authority over the Church and authority over the State should never be given to the same individual.

120

Galloway’s phrases not only provided clear and easily understandable visual pictures, but also referenced specific historical incidents—as when Period II Roman Emperor Otto III (980–1002 AD) constructed his king’s crown to fit atop the miter worn by Church officials.19 This type of jurisdictional blending had been common in England before American colonization, as when the English Parliament passed civil laws stipulating who could take communion in the church or who could be a minister of the Gospel, thus governmentally controlling what should have been purely ecclesiastical matters.20

It is important to note that it was not secular civil leaders who emphasized a separation of the Church from the control of the State but rather Bible-based ministers. In fact, it was English Reformation clergyman Reverend Richard Hooker who first used the phrase during the reign of England’s King Henry VIII, calling for a “separation of . . . Church and Commonwealth.”21 (Recall that Henry had wanted a divorce, but when the Church refused to give it, he simply started his own national church—the Anglican Church—and gave himself a divorce under his new state-established doctrines.22)

Other Bible-centered ministers also spoke out against the intrusion of the State into the jurisdiction of the Church, including the Reverend John Greenwood (1556–1593) who started the church attended by many of the Pilgrims when they still lived in England.

121

Queen Elizabeth was head over both the State and the Church at that time, but Greenwood asserted “that there could be but one head to the church and that head was not the Queen, but Christ!”23 He was eventually executed for “denying Her Majesty’s ecclesiastical supremacy and attacking the existing ecclesiastical order.”24

Then, when Parliament passed a law requiring that if “any of her Majesty’s subjects deny the Queen’s ecclesiastical supremacy . . . they shall be committed to prison without bail,”25 most of the Pilgrims fled from England to Holland. From Holland they went to America where they boldly advocated separation of church and state, affirming that government had no right to “compel religion, to plant churches by power, and to force a submission to ecclesiastical government by laws and penalties.”26

Many other reformation-minded ministers and colonists traveling from Europe to America also openly advocated the institutional separation of State and Church, including the Reverends Roger Williams (1603–1683),27 John Wise (1652–1725),28 William Penn (1614–1718),29 and many others. In fact, they often did so in language even more articulate than the original Reformers.30

The entire history of the separation doctrine centered around preventing the State from taking control of the Church, and meddling with or controlling its doctrines or punishing its religious expressions. Throughout history, it had not been the Church that had seized the State but just the opposite. Furthermore, the separation doctrine had never been used to secularize the public square. As affirmed by early Quaker leader Will Wood, “The separation of Church and State does not mean the exclusion of God, righteousness, morality, from the State.”31

Early Methodist bishop Charles Galloway agreed: “The separation of the Church from the State did not mean the severance of the State from God, or of the nation from Christianity.”32

122

The philosophy of keeping the State limited and at arm’s length from regulating or punishing religious practices and expressions was planted deeply into American thinking. Eventually, it was nationally enshrined in the First Amendment, which states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the Free Exercise thereof.”

The first part of the Amendment is now called the establishment clause and the latter part, the free exercise clause. The language of both is clear; and both clauses were pointed solely at the State not the Church. Notice that the establishment clause prohibited the State from enforcing religious conformity, and the free exercise clause ensured that the State would protect—rather than suppress, as it currently does—citizens’ rights of conscience and religious expression. Both clauses are prohibitions only on the power of Congress (i.e., the government), not on religious individuals or organizations.

This was the meaning of “separation of church and state” with which Jefferson was intimately familiar, and it was this interpretation, and not the modern perversion of it, that he repeatedly reaffirmed in his writings and practices. This is especially evident in his famous letter containing the separation phrase. Consider the background of that letter and why Jefferson wrote it.

When Jefferson, the head of the Anti-Federalists, became president in 1801, his election was particularly well received by Baptists. This political disposition was understandable, for from the early settlement of Rhode Island in the 1630s to the time of the writing of the federal Constitution in 1787, the Baptists had often found their free exercise limited by state-established government power. Baptist ministers had often been beaten, imprisoned, and even faced death by those from the government church,33 so it was not surprising that they strongly opposed centralized government power. For this reason the predominately Baptist state of Rhode Island refused to send delegates to the Constitutional Convention;34 and the Baptists were the only denomination in which a majority of its clergy across the nation voted against the ratification of the Constitution.35

123

Jefferson’s election as an Anti-Federalist opposed to a strong central government elated the Baptists. They were very familiar with Jefferson’s record not only of disestablishing the official church in Virginia but also of championing the cause of religious freedom for Baptists and other denominations.36 Not surprisingly, therefore, he received numerous letters of congratulations from Baptist organizations.37

One of them was penned on October 7, 1801, by the Baptist Association of Danbury, Connecticut. Their letter began with an expression of gratitude to God for Jefferson’s election followed by prayers of blessing for him. They then expressed grave concern over the proposed government protections for their free exercise. As they explained:

Our sentiments are uniformly on the side of religious liberty—that religion is at all times and places a matter between God and individuals; that no man ought to suffer in name, person, or effects on account of his religious opinions; that the legitimate power of civil government extends no further than to punish the man who works ill to his neighbor. But sir, our constitution of government is not specific. . . . Religion is considered as the first object of legislation and therefore what religious privileges we enjoy (as a minor part of the State) we enjoy as favors granted and not as inalienable rights.38

These ministers were troubled that their “religious privileges” were being guaranteed by the apparent generosity of government.

Many citizens today do not grasp their concern. Why would ministers object to the State guaranteeing their enjoyment of religious privileges? Because to the far-sighted Danbury Baptists, the mere presence of governmental language protecting their free exercise of religion suggested that it had become a government-granted right (and thus alienable) rather than a God-given one (and hence inalienable). Fearing that the inclusion of such language in governing documents might someday cause the government wrongly to believe that since it had “granted” the freedom of religious expression it therefore had the authority to regulate it, the Danbury Baptists had strenuously objected. They believed that government should not interfere with any public religious expression unless, as they told Jefferson, that religious practice caused someone to genuinely “work ill to his neighbor.”39

124

The Danbury Baptists were writing to Jefferson fully understanding that he was an ally of their viewpoint, not an adversary of it. After all, three years earlier in his famous Kentucky Resolution of 1798 Jefferson had already emphatically declared:

[N]o power over the freedom of religion . . . [is] delegated to the United States by the Constitution [the First Amendment].40

Jefferson believed that the federal government had no authority to interfere with, limit, regulate, or prohibit public religious expressions—a position he repeated on many subsequent occasions:

In matters of religion I have considered that its free exercise is placed by the Constitution independent of the powers of the general [federal] government.41

[O]ur excellent Constitution . . . has not placed our religious rights under the power of any public functionary.42

None of these or any other statements of Jefferson contain even the slightest suggestion that religion should be removed from the public square or that the square should be secularized, but rather only that the government could not limit or regulate it—which is what had concerned the Danbury Baptists. Understanding this, Jefferson replied to them on January 1, 1802, assuring them that they had nothing to fear: the government would not meddle with their religious expressions.

125

Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God; that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship; that the legislative powers of government reach actions only and not opinions; I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should “make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between Church and State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties. I reciprocate your kind prayers for the protection and blessing of the common Father and Creator of man, and tender you, for yourselves and your religious association, assurances of my high respect and esteem.43

The separation metaphor was a phrase already commonly used and well understood by the government-oppressed Baptists and their ministers, and Jefferson used it to assure them that the government would protect rather than impede their religious beliefs and expressions. As James Adams noted:

Jefferson’s reference to a “wall of separation between Church and State” . . . was not formulating a secular principle to banish religion from the public arena. Rather he was trying to keep government from darkening the doors of Church.44

126

The first occasion in which the US Supreme Court invoked the separation metaphor from Jefferson’s letter was in 1878 when the Court affirmed that the purpose of separation was to protect rather than limit public religious expressions.45 In fact, after reprinting lengthy portions of Jefferson’s letter and reviewing its general prohibition against federal intrusion into religious beliefs and the free exercise of religion, the Court concluded:

[I]t [Jefferson’s letter] may be accepted almost as an authoritative declaration of the scope and effect of the Amendment thus secured. Congress was deprived of all legislative power over mere [religious] opinion, but was left free to reach actions which were in violation of social duties or subversive of good order.46

Then to affirm Jefferson’s point that there were only a handful of religious expressions against which the federal government could legitimately interfere, the Court quoted from his famous Virginia Statute to establish that:

[T]he rightful purposes of civil government are for its officers to interfere when principles break out into overt acts against peace and good order. In th[is] . . . is found the true distinction between what properly belongs to the Church and what to the State.47

Notice that in Jefferson’s view, the only religious expressions that the government could hamper were acts “against peace and good order,” “injurious to others,” acts “subversive of good order,” or acts by “the man who works ill to his neighbor.”

That Court (and others48) then identified a handful of actions that, if perpetrated in the name of religion, the government did have legitimate reason to limit, including bigamy, concubinage, incest, child sacrifice, infanticide, parricide, and other similar crimes. But the government was not to impede traditional religious expressions in public, such as public prayer, public display of religious symbols, public use of Scriptures, acknowledgement of God in public events, and so on. In short, the separation of Church and State existed not to remove or secularize the free exercise of religion but rather to preserve and protect it, regardless of whether it was exercised in private or public.

127

This was the universal understanding of separation of Church and State—until the Court’s landmark ruling in 1947 in Everson v. Board of Education in which it announced it would reverse this historic meaning.49 In that case the Court cited only Jefferson’s eight-word separation metaphor, completely severing the phrase from its historical context and the rest of Jefferson’s clearly worded letter, and then expressed for the first time that the phrase existed not to protect religion in the public square but to remove it.

The next year, in 1948, the Court repeated its rhetoric of the previous year declaring:

[T]he First Amendment has erected a wall between Church and State which must be kept high and impregnable.50

The Court again refused to reference Jefferson’s full (and short) letter, and it again applied Jefferson’s eight-word phrase in a religiously hostile manner, using it to enforce an ardent public secularism.

Amazingly, in that case the Court had ruled that a school in Illinois had made the egregious mistake of allowing voluntary religious activities by students, a practice that had characterized American education for the previous three centuries. The permitted religious activity had actually been so voluntary that students were allowed to participate only with the written consent of their parents.51 But an atheist had objected not to what her own children were doing with religious expressions but to what other parents were letting their children do—attend a voluntary religious class. The Court therefore struck down those individual voluntary activities, demanding that the school remain aggressively and rigidly secular. It ruled that the school should no longer permit the constitutionally guaranteed free exercise of religion even for those who wished to enjoy it. For the first time the separation metaphor had become a rigid, callous phrase no longer allowing or accommodating voluntary religious activities in a public setting. The result of the Court’s twisting of Jefferson’s phrase was that the First Amendment was no longer a prohibition on the government but rather on individuals.

128

Courts have subsequently pushed that original misinterpretation of separation increasingly outward to the point where they have decided the First Amendment’s injunction that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof” now means:

• an individual student may not say a voluntary prayer at a football game,52 graduation,53 or any other school event54

• cadets at military academies may not engage in offering voluntary prayers over their meals55

• a choir may not sing a religious song as part of a school concert56

• a school may not place a Bible in a classroom library57

• an individual student may not write a research paper on a religious topic,58 draw religious artwork in an art class,59 or carry his personal Bible onto school grounds60

Significantly, none of these activities pertains to “Congress making a law,” which is the only body and the only activity proscribed by the First Amendment. But ignoring that succinct stricture, the modern misapplication of the historic separation doctrine now routinely results in egregious decisions:

• A state employee in Minnesota was barred from parking his car in the state parking lot because he had a religious sticker on his bumper.61

• A five-year-old kindergarten student in Saratoga Springs, New York, was forbidden to say a prayer over her lunch and was scolded by a teacher for doing so.62

• A military honor guardsman was removed from his position for saying, “God bless you and this family, and God bless the United States of America” while presenting a folded flag to a family during a military funeral—a statement that the family requested be made at the funeral.63

• Senior citizens meeting at a community senior center in Balch Springs, Texas, were prohibited from praying over their own meals.64

• A library employee in Russellville, Kentucky, was barred from wearing her necklace because it had a small cross on it.65

• College students serving as residential assistants in Eu Claire, Wisconsin, were prohibited from holding Bible studies in their own private dorm rooms.66

• A third grader in Orono, Maine, who wore a T-shirt containing the words “Jesus Christ” was required to turn the shirt inside out so the words could not be seen.67

• A school official in Saint Louis, Missouri, caught an elementary student praying over his lunch; he lifted the student from his seat, reprimanded him in front of the other students, and took him to the principal, who ordered him to stop praying.68

130

• In cities in Texas, Indiana, Ohio, Georgia, Kansas, Michigan, Pennsylvania, California, Nebraska, and elsewhere citizens were not permitted to hand out religious literature on public sidewalks or preach in public areas and were actually arrested or threatened with arrest for doing so.69

And there are literally hundreds of similar examples.70

Is this what Jefferson intended? Did he want to prohibit citizens from expressing their faith publically? Was he truly a secularist who wanted a stridently religion-free public square? His words certainly do not indicate this to be his desire; but how about his actions? After all, actions speak louder than words.

Jefferson’s actions in this area are completely consistent with his words. He has an extremely long and consistent record of deliberately and intentionally including rather than excluding religious expressions and activities in the public arena.

For example, in 1773, following the Boston Tea Party protest against oppressive British policy, Parliament retaliated with the Boston Port Bill to blockade the harbor and eliminate its trade, thus hoping to financially cripple the Americans and force them into submission. The blockade was to take effect on June 1, 1774. Upon hearing of this Jefferson introduced a measure in the Virginia legislature calling for a public day of fasting and prayer to be observed on that same day “devoutly to implore the Divine interposition in behalf of an injured and oppressed people”71 He also recommended that legislators “proceed with the Speaker and the Mace to the Church . . . and that the Reverend Mr. Price be appointed to read prayers, and the Reverend Mr. Gwatkin to preach a sermon suitable to the occasion.”72 Additionally, Jefferson wrote home to his local church community in Monticello urging them also to arrange a special day of prayer and worship at “the new church on Hardware River”73—a service which Jefferson attended.74

131

In 1776, while serving in the Continental Congress, he was placed on a committee of five to draft the Declaration of Independence. He was the principal author of that document, and he incorporated four explicit, open acknowledgments of God, some made by his own hand and some added by Congress. Jefferson’s Declaration was actually a dual declaration: of independence from Great Britain and dependence on God.

On July 4, 1776, Jefferson was placed on a committee of three to draft an official seal for the new American government. His recommendation was from the Bible: “The children of Israel in the wilderness, led by a cloud by day, and a pillar of fire by night.”75

In 1779 Jefferson became the governor of Virginia and introduced several bills into the state legislature, including:

• A Bill for Punishing Disturbers of Religious Worship and Sabbath Breakers76

• A Bill for Appointing Days of Public Fasting and Thanksgiving77

• A Bill Annulling Marriages Prohibited by the Levitical Law and Appointing the Mode of Solemnizing Lawful Marriage78

• A Bill for Saving the Property of the Church Heretofore by Law Established79

Jefferson personally penned the language for each proposal, and there was no hint of public secularism in any of them; instead, it was just the opposite. For example, Jefferson’s bill for preserving the Sabbath stipulated:

If any person on Sunday shall himself be found laboring at his own or any other trade or calling . . . except that it be in the ordinary household offices of daily necessity or other work of necessity or charity, he shall forfeit the sum of ten shillings for every such offence.80

132

His bill for public days of prayer declared:

[T]he power of appointing Days of Public Fasting and Thanksgiving may be exercised by the Governor. . . . Every minister of the Gospel shall, on each day so to be appointed, attend and perform Divine service and preach a sermon or discourse suited to the occasion in his church, on pain of forfeiting fifty pounds for every failure, not having a reasonable excuse.81

His bill for protecting marriage stipulated:

Marriages prohibited by the Levitical law shall be null; and persons marrying contrary to that prohibition and cohabitating as man and wife, convicted thereof in the General Court, shall be [fined] from time to time until they separate.82

Jefferson also introduced a Bill for Establishing General Courts in Virginia, requiring:

Every person so commissioned . . . [shall] take the following oath of office, to wit, “You shall swear. . . . So help you God.”83

Clearly, Jefferson introduced many religious activities directly into civil law.

In 1780, while still serving as governor, Jefferson ordered that an official state medal be created with the religious motto “Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God.”84 This phrase had been proposed to Congress in 1776 as part of the new national seal,85 and Jefferson also placed it on his own personal seal.86

In 1789 Thomas Jefferson began his federal career as secretary of state to President George Washington. One of his early assignments was to oversee the layout and construction of Washington, DC.87 The plan for the city was approved by Jefferson in 1791, and in 1793 construction began on permanent federal buildings such as the White House and the Capitol. Work proceeded rapidly, and by 1795 the structure had progressed far enough that Secretary Jefferson approved a special activity in the Capitol that was still under construction. Newspapers as far away as Boston happily reported:

133

City of Washington, June 19. It is with much pleasure that we discover the rising consequence of our infant city. Public worship is now regularly administered at the Capitol, every Sunday morning at 11 o’clock, by the Reverend Mr. Ralph.88

From 1797 to 1801 Jefferson served as vice president of the United States under President John Adams. During that time, on November 22, 1800, Congress moved into the new Capitol. Two weeks later, on December 4, 1800, with Theodore Sedgwick presiding over the House and Vice President Thomas Jefferson presiding over the US Senate, Congress approved a plan whereby Christian church services would be held each Sunday in the Hall of the House of Representatives,89 the largest room in the Capitol building.The spiritual leadership for each Sunday’s service would alternate between the chaplain of the House and the chaplain of the Senate, who would either personally conduct the service or invite an outside minister to preach.

It was in this most recognizable of all government buildings, the US Capitol, that Vice President Jefferson attended church.90 This was a practice he continued throughout his two terms as president.91 In fact, US congressman Manasseh Cutler, who also attended church at the Capitol, affirmed that “[h]e [Jefferson] and his family have constantly attended public worship in the Hall.”92 Mary Bayard Smith, another attendee at the Capitol services, confirmed, “Mr. Jefferson during his whole administration, was a most regular attendant.”93 She even noted that Jefferson had a designated seat at the Capitol church: “The seat he chose the first Sabbath, and the adjoining one, which his private secretary occupied, were ever afterwards by the courtesy of the congregation left for him and his secretary.”94

134

For those services Jefferson rode his horse from the White House to the Capitol,95 a distance of 1.6 miles and a trip of about twenty minutes. He made this ride regardless of weather conditions. Among Representative Cutler’s entries is one noting that “[i]t was very rainy, but his [Jefferson’s] ardent zeal brought him through the rain and on horseback to the Hall.”96 Other diary entries similarly confirm Jefferson’s faithful attendance despite bad weather.97

President Jefferson personally contributed to the worship atmosphere of the Capitol church by having the Marine Band play at the services.98 According to attendee Margaret Bayard Smith, the band, clad in their scarlet uniforms, made a “dazzling appearance” as they played from the gallery, providing instrumental accompaniment for the singing.99 However, good as they were, they seemed too ostentatious for the services and “the attendance of the Marine Band was soon discontinued.”100

Under President Jefferson Sunday church services were also started at the War Department and the Treasury Department,101 which were two government buildings under his direct control. Therefore, on any given Sunday, worshippers could choose between attending church at the US Capitol, the War Department, or the Treasury Department, all with the blessing and support of Jefferson.

Why was Jefferson such a faithful participant at the Capitol church? He once explained to a friend while they were walking to church together:

No nation has ever yet existed or been governed without religion—nor can be. The Christian religion is the best religion that has been given to man and I, as Chief Magistrate of this nation, am bound to give it the sanction of my example.102

135

By 1867 the church in the Capitol had become the largest church in Washington.103

Other presidential actions of Jefferson include:

• Urging the commissioners of the District of Columbia to sell land for the construction of a Roman Catholic Church, recognizing “the advantages of every kind which it would promise” (1801)104

• Writing a letter to Constitution signer and penman Gouverneur Morris (then serving as a US senator) describing America as a Christian nation, telling him that “we are already about the 7th of the Christian nations in population, but holding a higher place in substantial abilities” (1801)105

• Signing federal acts setting aside government lands so that missionaries might be assisted in “propagating the Gospel” among the Indians (1802, and again in 1803 and 1804)106

• Directing the secretary of war to give federal funds to a religious school established for Cherokees in Tennessee (1803)107

• Negotiating and signing a treaty with the Kaskaskia Indians that directly funded Christian missionaries and provided federal funding to help erect a church building in which they might worship (1803)108

• Assuring a Christian school in the newly purchased Louisiana Territory that it would enjoy “the patronage of the government” (1804)109

136

• Renegotiating and deleting from a lengthy clause in the 1797 United States treaty with Tripoli110 the portion that had stated “the United States is in no sense founded on the Christian religion” (1805)111

• Passing “An Act for Establishing the Government of the Armies” in which:

It is earnestly recommended to all officers and soldiers diligently to attend Divine service; and all officers who shall behave indecently or irreverently at any place of Divine worship shall, if commissioned officers, be brought before a general court martial, there to be publicly and severely reprimanded by the President [Jefferson]; if non-commissioned officers or soldiers, every person so offending shall [be fined]112 (1806) (emphasis added)

• Declaring that religion is “deemed in other countries incompatible with good government, and yet proved by our experience to be its best support”113 (1807)

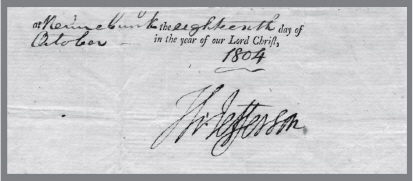

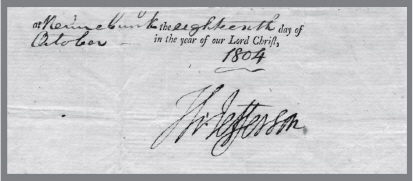

• Closing presidential documents with the appellation, “In the year of our Lord Christ”114 (1801–1809; see inset)

137

There are many additional examples, and they all clearly demonstrate that Jefferson has no record of attempting to secularize the public square. Furthermore, all of his religious activities at the federal level occurred after the First Amendment had been adopted, showing that he saw no violation of the First Amendment in any of his actions. In fact, no one did—not even his enemies. No one ever raised a voice of dissent against Jefferson’s federal religious practices; no one claimed that they were improper or that they violated the Constitution.

The only voice of objection ever raised was to complain that President Jefferson, unlike his predecessors George Washington and John Adams, did not issue any national prayer proclamations. This absence of a national prayer proclamation by Jefferson is cited by critics today as definitive proof of Jefferson’s public secularism.

For example, Supreme Court Justices William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall noted in Marsh v. Chambers that:

Thomas Jefferson . . . during [his] respective terms as President, refused on Establishment Clause [First Amendment] grounds to declare national days of thanksgiving or fasting.115

Justice Anthony Kennedy similarly noted in Allegheny v. ACLU:

In keeping with his strict views of the degree of separation mandated by the Establishment Clause, Thomas Jefferson declined to follow this tradition [of issuing national proclamations].116

Yet these justices are completely wrong. Jefferson himself pointedly stated that his refusal to issue national prayer proclamations was not because of any First Amendment scruples about religion but rather because of his specific views of Federalism—that the Constitution specifically limited the federal government but not the states or other government entities. He explained:

138

I consider the government of the United States [the federal government] as interdicted [prohibited] by the Constitution from intermeddling with religious institutions, their doctrines, discipline, or exercises. This results not only from the provision that “no law shall be made respecting the establishment or free exercise of religion” [the First Amendment], but from that also which reserves to the states the powers not delegated to the United States [the Tenth Amendment]. Certainly, no power to prescribe any religious exercise or to assume authority in religious discipline has been delegated to the general [federal] government. It must then rest with the states, as far as it can be in any human authority. But it is only proposed that I should recommend, not prescribe [require] a day of fasting and prayer. . . . I am aware that the practice of my predecessors may be quoted. But I have ever believed that the example of state executives [governors issuing prayer proclamations] led to the assumption of that authority by the general government [the president issuing prayer proclamations] without due examination, which would have discovered that what might be a right in a state government was a violation of that right when assumed by another.117

Jefferson made very clear that his refusal to issue federal prayer proclamations did not spring from any concerns over religious expressions in general but rather only from his view of federalism and which was the proper governmental jurisdiction. He believed that there was a limitation on the federal government’s ability to direct the states in which religious activities they could or should participate in, but he saw no such limitations on state or local governments. Actively encouraging public religious activities for citizens was well within their jurisdiction and completely appropriate and constitutional.

Because of his understanding of federalism, Jefferson refused to issue a presidential call for prayer, but he had certainly done so as a state leader. In addition to his 1774 Virginia legislative call for prayer,118 he called his fellow Virginians to a time of prayer and thanksgiving while serving as governor in 1779, asking the people to give thanks “that He hath diffused the glorious light of the Gospel, whereby through the merits of our gracious Redeemer we may become the heirs of the eternal glory.”119

139

He also asked Virginians to pray “that He would grant to His church the plentiful effusions of Divine grace and pour out his Holy Spirit on all ministers on the Gospel; that He would bless and prosper the means of education and spread the light of Christian knowledge through the remotest corners of the earth.”120

And Jefferson had personally penned the state bill “Appointing Days of Public Fasting and Thanksgiving.” He clearly was not opposed to official prayer proclamations, but he believed that this function was within the jurisdiction of governors, not presidents. Certainly, presidents before and after Jefferson did not agree with this view and regularly issued federal prayer proclamations, but the evidence shows that Jefferson’s refusal to do so was not because of any notion of secularism on his part but rather because of his view of federalism.

Jefferson’s record of including, advocating, and promoting religious activities and expressions in public is strong, clear, and consistent. He did not support a secular public square. The institutional separation of Church and State so highly praised by today’s civil libertarians did not originate from Jefferson or even from secularists—nor did it have societal secularization as its object. To the contrary, it was the product of Bible teachings and Christian ministers. Its object was the protection of religious activities and expressions whether in public or private.

140

Jefferson’s words and actions unequivocally demonstrate that he was not “a secular humanist,”121 nor did he in any manner seek to secularize the public square. This is simply another of the many modern Jefferson lies that has no basis in history.