Michael heard voices rising in his sons’ room but was watching the basketball game on TV and decided to wait for a commercial before investigating. Big mistake.

His eight-year-old, Graham, and Graham’s friend James had spent the last thirty minutes carefully organizing and categorizing Graham’s hundreds of Lego pieces. Graham had used his allowance to buy a fishing tackle box, and he had designated a different compartment for every Lego head, torso, helmet, sword, light saber, wand, axe, and anything else the creative geniuses from Denmark could dream up. The boys were in organizational heaven.

The problem was that Michael’s five-year-old, Matthias, had been feeling increasingly left out by Graham and James. The three boys had begun the project together, but the older boys eventually felt that Matthias didn’t quite understand their complex categorical system. As a result, they weren’t allowing him to participate in the activity.

Cue the rising voices.

Michael never made it to the commercial. The shouting let him know that he needed to intervene immediately, but he wasn’t quick enough. When he was still three steps away from the boys’ room—three short steps!—he heard the unmistakable sound of hundreds of plastic Lego pieces exploding across a hardwood floor.

Three steps later he witnessed the mayhem and carnage. It was a complete massacre. Decapitated heads littered the entire room, lying next to armless bodies and weapons both medieval and futuristic. A rainbow of chaos stretched from the doorway to the closet on the other side of the room.

Next to the upended tackle box stood Michael’s huffing, red-faced five-year-old, looking at him with eyes that were somehow both defiant and terrified. Michael turned to his older son, who yelled, “He ruins everything!” and ran from the room in tears, followed by a sheepish-looking and uncomfortable James.

Talk about a discipline moment. Both of his boys were now bawling, a friend was caught in the crossfire, and Michael himself felt furious. Not only had Matthias destroyed all the work the older boys had done, but now there was a huge mess to clean up in the room. (If you’ve ever felt the pain of stepping on a Lego piece, you know why it wasn’t an option to leave the bits spread out on the floor.) And he was missing the game.

Michael decided he’d go check on the older boys in a minute and address Matthias first. His initial inclination was to stand over his young son, wag his finger in his son’s face, and scold him for dumping the tackle box. In his anger he wanted to offer immediate consequences. He wanted to shout, “Why did you do this?” He wanted to say something about never again getting to participate in Graham’s playdates, then add, “Do you see why they didn’t want you to play with their Legos?”

Luckily, though, the thinking part of Michael (his upstairs brain) took over, and he addressed the situation from a Whole-Brain perspective. What triggered the more mature and empathic approach was his recognition of how much his little boy needed him right then. Of course Michael would have to address Matthias’s behavior. And yes, he’d obviously need to be a bit more proactive next time in attending to the situation before it spun out of control. He’d want to help Matthias think about how Graham felt, and understand that our actions often impact other people in significant ways. All of this teaching, all of this redirection, was absolutely necessary.

But not right now.

Right now, he needed to connect.

Matthias was completely dysregulated emotionally, and he needed his dad to soothe the hurt feelings, sadness, and anger that came from being criticized for being too little to understand and from being excluded. This was not the time to redirect, to teach, or to talk about family rules and respect for others’ property. It was time to connect.

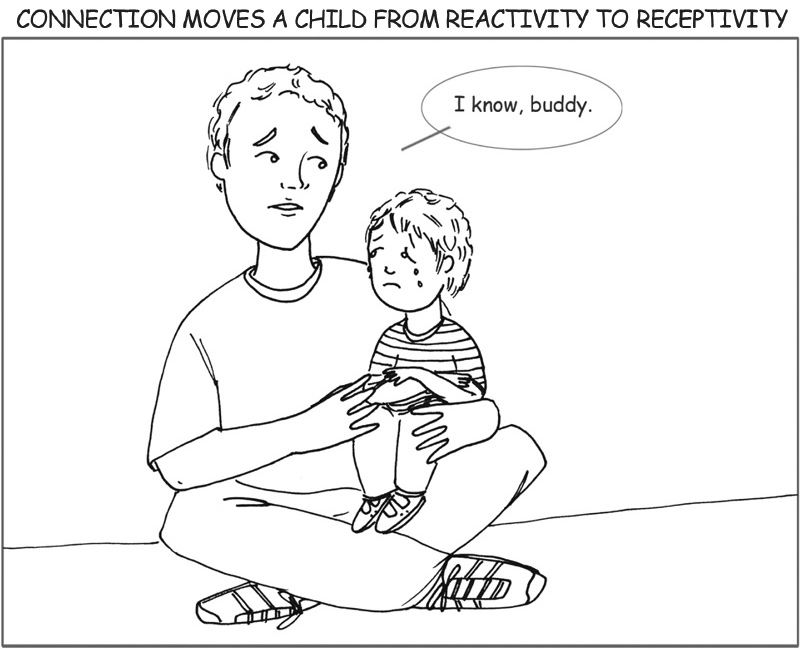

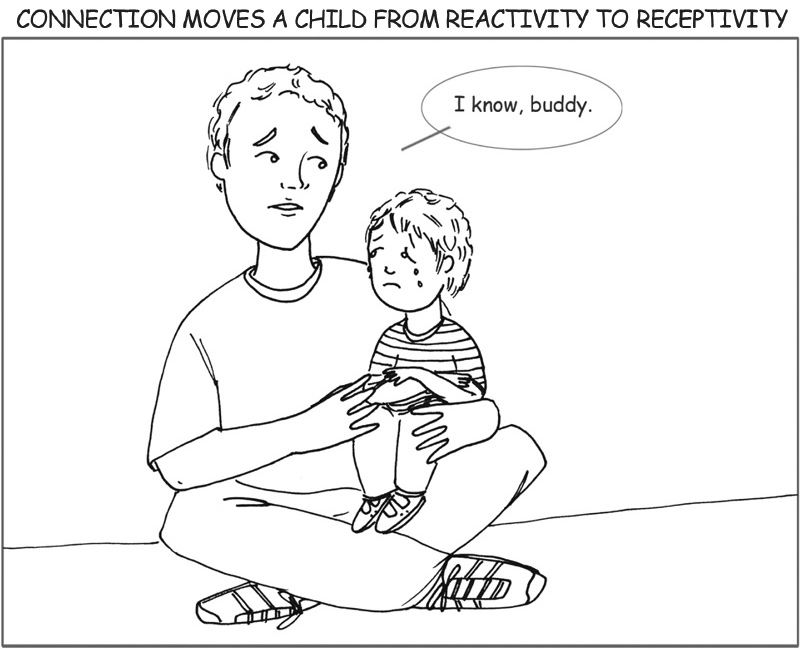

So Michael knelt down and opened his arms, and Matthias fell into them. Michael held him as he sobbed, rubbed his back, and said nothing other than an occasional “I know, buddy. I know.”

A minute later Matthias looked up at him, his eyes shiny with tears, and said, “I spilt the Legos.”

In response, Michael laughed a little and said, “I’d say you did more than that, little man!”

Matthias cracked a small smile, and at that point Michael knew he could now proceed to the redirecting part of the discipline and help Matthias understand some important lessons about empathy and appropriate expressions of big feelings. He was now capable of hearing his father. Michael’s connection and comfort had allowed his son to move out of a reactive state and into a receptive one, where he could hear his dad and really learn.

Notice that connecting first is not only more relational and loving. Yes, it allows parents to attune to their children, as Michael did here, and be emotionally responsive when they’re upset and dysregulated. That enables the child to “feel felt,” which is the inner sense of being seen and understood that transforms chaos into calm, isolation into connection. Connecting first is a fundamentally loving way to discipline. But notice how much more effective a No-Drama disciplinary approach can be as well. It’s not that a lecture would have been wrong as Michael’s initial response to the situation. Our point here isn’t about the rightness or wrongness of parenting approaches (although we’d definitely argue that a Whole-Brain approach is fundamentally more loving and compassionate). The point is that Michael’s connect-first tactic achieved the two goals of discipline—gaining cooperation and brain building—extremely effectively. It allowed learning to occur, teaching to be effective, and connection to be established and maintained. His approach let Michael get his son’s attention, and to do so quickly and without drama, so they could talk about Matthias’s behavior in such a way that he could listen. Plus, it could help build Matthias’s brain, because he could now hear Michael’s points and understand the important lessons his father was teaching him. In addition, Michael modeled for his son attuned connection and showed him that there are calmer, more loving ways to interact when you’re upset with someone. And all of this happened because Michael connected first, before redirecting.

We’ll talk in just a minute about why connection is such a powerful tool when our kids are upset or having trouble making good decisions. Michael obviously used it effectively. But by being just a bit slow to respond to the situation—three short steps!—he missed an opportunity to avoid the entire disciplinary process completely.

It really is true. At times we can avoid having to discipline at all, simply by parenting proactively, rather than reactively. When we parent proactively, we watch for times we can tell that misbehavior and/or a meltdown is in our children’s near future—it’s just over the horizon of where they are right now—and we step in and try to guide them around that potential landmine. Michael wanted to make it to the next commercial, so he didn’t respond quickly enough to the signs that trouble was beginning to surface in his sons’ room.

Parenting proactively can make all the difference. When, for example, your sweet and usually compliant eight-year-old is getting ready to go to her swim lesson, you might notice that she overreacts a bit when it’s time to apply sunscreen: “Why do I have to use sunscreen every day?” Then while you’re getting her little brother ready, she sits down at the piano for a minute to play one of her songs. But she misses a couple of notes, then slams her fist on the keyboard in frustration.

You could interpret these actions as isolated incidents and overlook them. Or you could recognize them for the warning flags they probably are. You might remember that this particular daughter gets especially upset when she’s hungry, so you might stop what you’re doing and set an apple in front of her. When she looks up at you, you can offer her a knowing smile as a reminder of this tendency of hers, and hopefully she’ll nod, eat the apple, and move back into a place of self-control.

Granted, sometimes no obvious signs present themselves before our kids make bad decisions and act in ways that aren’t ideal. But other times we can read our children’s cues and take proactive steps to stay ahead of the discipline curve. That might mean giving a warning five minutes before having to leave the park, or enforcing a consistent bedtime so your kids don’t get too tired and grumpy. It might mean starting to tell a preschooler a suspenseful story and then pausing it, explaining that you’ll tell what happens next once she’s in her car seat. Or maybe it means you step in to begin a new game when you hear that your children are moving toward significant conflict with each other. It might mean telling a toddler, with a voice full of intriguing energy, “Hey, before you throw that french fry across the restaurant, I want to show you what I have in my purse.”

Another way to parent proactively is to HALT before responding to your kids. When you see your child’s behavior trending in a direction you don’t like, ask yourself, “Is he hungry, angry, lonely, or tired?” It may be that all you need to do is to set out some raisins, listen to his feelings, play a game with him, or help him get more sleep. Sometimes, in other words, all you need is a bit of forethought and planning ahead.

Parenting proactively isn’t easy, and it takes a fair amount of awareness on your part. But the more you can watch for the beginnings of negative behaviors and head them off at the pass, the less you’ll end up having to pick up the literal or figurative pieces, meaning you and your children will have more time simply to enjoy each other.

As we all know, though, sometimes misbehavior just happens. Oh, does it happen. And no amount of proactivity can prevent it. That’s when it’s time to connect. We have to fight the urge to immediately punish, lecture, lay down the law, or even positively redirect right away. Instead, we need to connect.

Let’s get more specific and talk about why connection is so powerful. We’ll look at three primary benefits—one short-term, one long-term, and one relational—of making connection our first response when our kids have trouble controlling themselves and making good decisions.

However we decide to specifically respond when our children misbehave, there’s one thing we have to do: we must remain emotionally connected with them, even when—and perhaps especially when—we discipline. After all, it’s when our kids are most upset that they need us the most. Think about it: they don’t want to feel frustrated, enraged, or out of control. That’s not only unpleasant, it’s extremely stressful. Usually misbehavior is the result of a child having a hard time dealing with what’s going on around her—and inside her. She’s got all these big feelings she doesn’t yet have the capacity to manage, and the misbehavior is simply the result. Her actions—especially when she’s out of control—are a message that she needs help. They are a bid for assistance, and for connection.

So when children feel furious, dejected, ashamed, embarrassed, overwhelmed, or out of control in any other way, that’s when we need to be there for them. Through connection, we can soothe their internal storm, help them calm down, and assist them in making better decisions. When they feel our love and acceptance, when they “feel felt” by us, even when they know we don’t like their actions (or they don’t like ours), they can begin to regain control and allow their upstairs brains to engage again. When that happens, effective discipline can actually take place. Connection, in other words, moves them out of a reactive state and into a state where they can be more receptive to the lesson we want to teach and to the healthy interactions we want to share with them.

So there’s a great question we can ask ourselves before we begin redirecting and explicitly teaching: Is my child ready? Ready to hear me, ready to learn, ready to understand? If a child isn’t ready, then more connection is most likely in order.

As we saw with Michael and his five-year-old, connection calms the nervous system, soothing children’s reactivity in the moment and moving them toward a place where they can hear us, learn, and even make their own Whole-Brain decisions. When the emotional gauge gets turned up, connection is the modulator that keeps the feelings from getting too high. Without connection, emotions can continue to spiral out of control.

Imagine the last time you felt really sad or angry or upset. How would it have felt if someone you love told you, “You need to calm down,” or “It’s not that big a deal”? Or what if you were told to “go be by yourself until you’re calm and ready to be nice and happy”? These responses would feel awful, wouldn’t they? Yet these are the kinds of things we tell our kids all the time. When we do, we actually increase their internal distress, leading to more acting out, not less. These responses accomplish the opposite of connection, effectively amplifying negative states.

Connection, on the other hand, calms, allowing children to begin to regain control of their emotions and bodies. It allows them to “feel felt,” and this empathy soothes the sense of isolation or being misunderstood that arises with the reactivity of their downstairs brain and the whole nervous system: heart pounding, lungs rapidly breathing, muscles tightening, and intestines churning. Those reactive states are uncomfortable, and they can become intensified with further demands and disconnection. With connection, however, kids can make more thoughtful choices and handle themselves better.

What connection does, essentially, is to integrate the brain. Here’s how it works. The brain, as we’ve said, is complex. (That’s the third Brain C.) It’s made up of many parts, all of which have different jobs to do. The upstairs brain, the downstairs brain. The left side and the right side. There are memory centers and pain regions. Along with all the systems and circuitry of the brain, these parts of our brain have their own responsibilities, their own jobs to do. When they work together as a coordinated whole, the brain becomes integrated. Its many parts can perform as a team, accomplishing more and being more effective than they could working on their own.

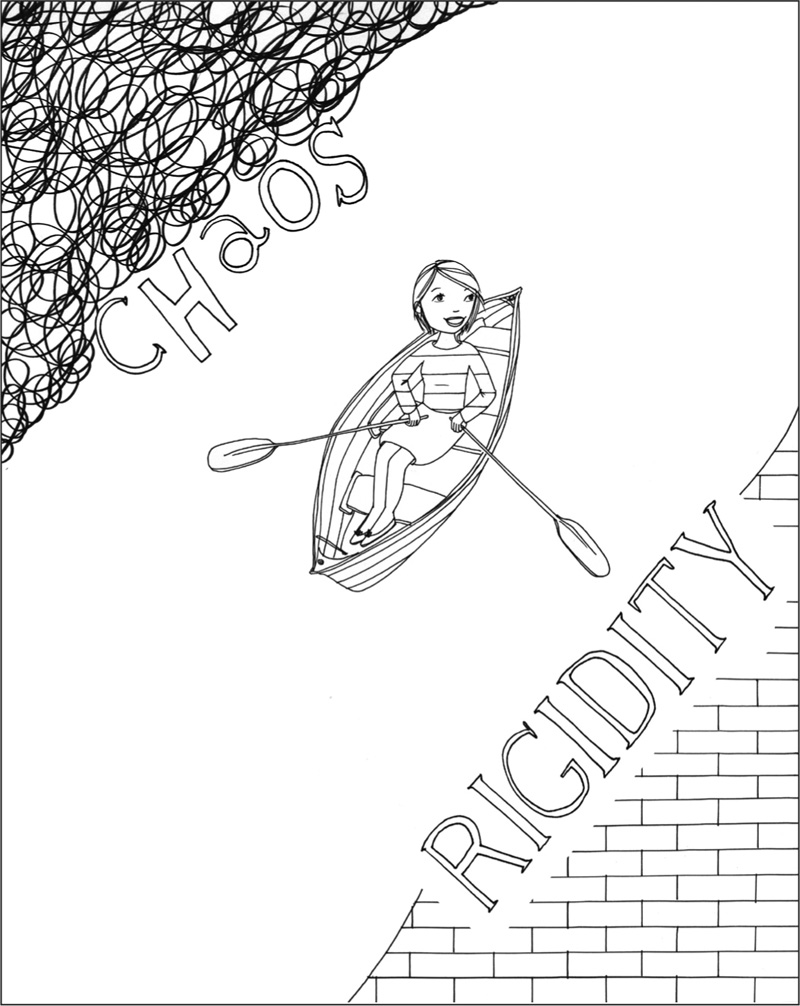

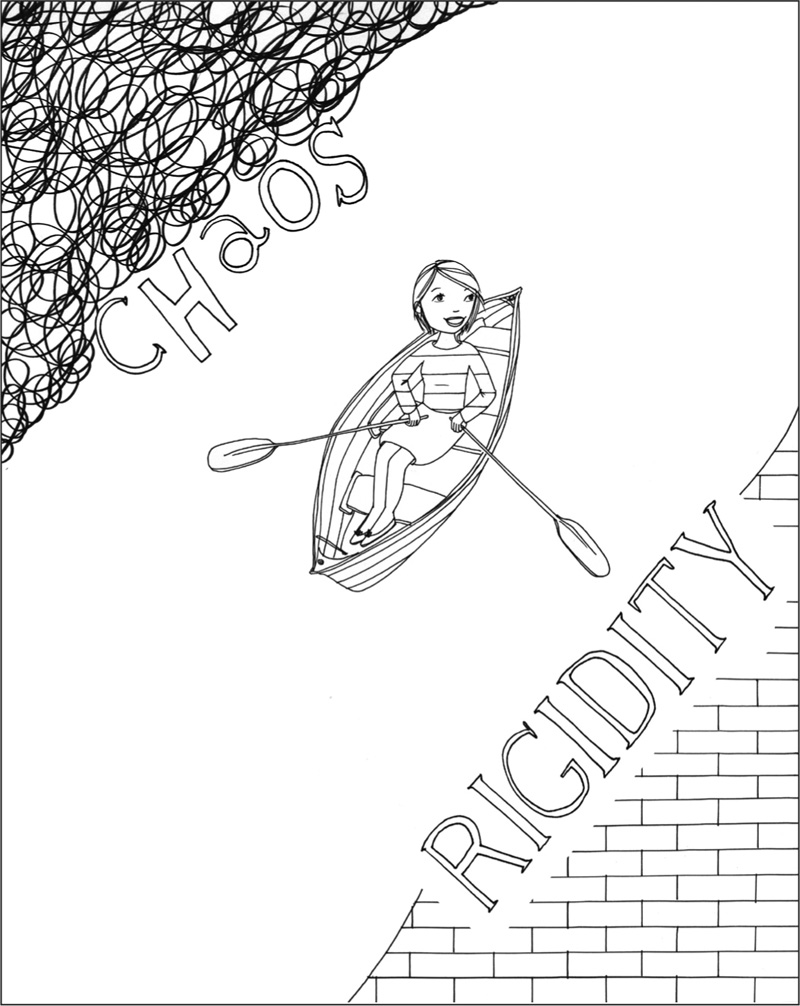

As we explained in The Whole-Brain Child, a good image to help understand integration is a river of well-being. Imagine you’re in a canoe, floating along in a peaceful, idyllic river. You feel calm, relaxed, and ready to deal with whatever comes along. It’s not necessarily that everything’s perfect or going your way. It’s more that you’re in an integrated state of mind—you’re calm, receptive, and balanced, and your body feels energetic and at ease. Even when things don’t work out the way you’d like, you can flexibly adapt. That’s the river of well-being.

Sometimes, though, you’re not able to stay in the flow of the river. You veer too far to one bank or the other. One side of the river represents chaos. Near this bank are dangerous rapids that make life feel frenzied and unmanageable. When you’re near the chaos bank, you’re easily upset, and even minor obstacles can leave you spinning out of control. You might experience overwhelming emotions such as high anxiety or intense anger, and you might notice that your body feels chaotic, too, with tense muscles, a rapid heartbeat, and a furrowed brow.

The other bank is no less unpleasant, because it represents rigidity. Here you get stuck desiring or expecting the world to operate in one particular way, and you’re unwilling or unable to adapt when it doesn’t. In your effort to impose your own vision and desires on the world around you, you find that you won’t, or possibly even can’t, compromise or negotiate in any meaningful way.

So chaos is on one bank, rigidity on the other. The two extremes offer either a lack of control or so much control that there’s no flexibility or adaptability. And both extremes keep you out of the peaceful flow of the river of well-being. Whether you’re chaotic or rigid, you’re missing out on the opportunity to enjoy mental and emotional health, to feel at ease with the world.

Think about the river of well-being in relation to your kids. Almost always, when children act up or feel upset, they will display evidence of chaos, rigidity, or both. When a nine-year-old freaks out about an oral presentation at school the next day and ends up ripping up her notes as she sobs that she’ll never be able to memorize her opening, she’s succumbed to chaos. She’s crashed into the bank, far from the smooth-flowing river of well-being. Similarly, when a five-year-old stubbornly insists on another bedtime story or refuses to get in the tub until he finds his most special wristband, he’s right up against the rigidity bank. And remember Nina from the last chapter? When she fell apart because her mom told her that her dad would be driving her to school that morning, then refused to consider any alternative perspectives on the situation, she was zigzagging back and forth between chaos and rigidity, never getting to enjoy the peaceful flow in the center of the river of well-being.

So that’s what connection does. It moves children away from the banks and back into the flow, where they experience an internal sense of balance and feel happier and more stable. Then they can hear what we need to tell them, and they can make better decisions. When we connect with a child who feels overwhelmed and chaotic, we help move her away from that bank and into the center of the river, where she can feel more balanced and in control. When we connect with a child who’s stuck in a rigid frame of mind, unable to consider alternative perspectives, we help him integrate so that he can loosen his unyielding grip on a situation and become more flexible and adaptive. In both cases, connection creates an integrated state of mind, and the opportunity for learning.

We’ll get much more specific in the next chapter about practical ways to connect with your children when they’re upset. The basic approach, though, usually entails listening and providing lots of verbal and nonverbal empathy. This is how we attune to our children, tuning in to the inner life of their mind—to their feelings and thoughts, to their perceptions and memories, to what has inner subjective meaning in their lives. This is tuning in to the mind beneath their behavior. For example, one of the most powerful ways we connect with our children is simply by physically touching them. A loving touch—as simple as a hand on an arm or a rub on the back or a warm embrace—releases feel-good hormones (like natural oxytocin and opioids) into our brain and body, and decreases the level of our stress hormone (cortisol). When your children are feeling upset, a loving touch can calm things down and help you connect, even during moments of high stress. This is connecting with their inner distress, not simply reacting to their outwardly visible behavior.

Notice that this was the first thing Michael did when he looked at his young son in the middle of the Lego carnage: he sat down and held him.

In doing so, he began to pull Matthias’s tiny canoe away from the bank of chaos and back into the peaceful flow of the river. Then he listened. Matthias didn’t need to say much: “I spilt the Legos.” With that he could begin to move on. Sometimes children will need to talk much more, and to be listened to for much longer. Or sometimes they don’t want to talk. And sometimes it can be as quick as it was here. Nonverbal touch, an empathic statement—“I know, buddy”—and a willingness to listen. That’s what Matthias needed in order to return some equilibrium to his young brain and impulsive body. Once that happened, his father could begin to teach him by talking about the lessons at hand.

Even though Michael wasn’t thinking in these terms, what he was doing was using his relationship, his connecting communication, to help bring integration to Matthias’s brain, so that his upstairs brain and his downstairs brain could work together, and so that the right and left sides of his brain could work together. When Matthias became furious with the older boys, his downstairs brain completely took over, disabling his upstairs brain. The instinctive, reactive lower parts of his brain became so active that he lost access to the higher parts of the brain, the ones that help him think about consequences and consider others’ feelings. These two parts of his brain were not working together. In other words, his brain in that moment was dis-integrated, and the result was the Lego massacre. By offering a nonverbal gesture instead of just a bunch of logical, left-brained words, Michael was able to connect with Matthias’s right brain, the side more directly connected to and also flooded by the downstairs brain. Right and left, downstairs and upstairs, Matthias’s brain was ready to become more coordinated and balanced in its movement toward integration. Connection integrated his emotion-focused downstairs brain and his thinking-oriented upstairs brain and allowed Michael to achieve the short-term goal of gaining cooperation from his son.

As we explained in the previous chapter, No-Drama Discipline builds the brain of a child by improving his capacity for relationships, self-control, empathy, personal insight, and much more. We discussed the importance of setting limits, creating structure, and helping children build internal controls and impulse inhibition by internalizing “no.” This is how we use our relationship with our children to build their brains’ executive functions. We also discussed other ways to develop a child’s relational and decision-making abilities. Each interaction with our kids offers the opportunity to build their brains and further their capacity to be the kind of people we hope they’ll be.

And it all begins with connection. In addition to the short-term benefit of moving them from reactivity to receptivity, connecting during a disciplinary interaction also impacts children’s brains in ways that will have long-term effects as they grow up. When we offer comfort when our kids are upset, when we listen to their feelings, when we communicate how much we love them even when they’ve messed up: when we respond in these ways, we significantly impact the way their brains develop and the kind of people they’ll be, both now and as they move into adolescence and adulthood.

In upcoming chapters we’ll talk more about redirection, including the explicit lessons we teach and the behaviors we model as we interact with our children. Obviously, a child’s brain will be greatly impacted by what we communicate to him when we respond to misbehavior. And it will also be changed by what we model with our own actions in the moment. Whether consciously or subconsciously, a child’s brain will assimilate all kinds of information based on the parental response to any situation. The more pertinent point here is about connection, and how parents change and even build children’s brains based on what children experience in that disciplinary moment.

To put it in more neurological terms, connection strengthens the connective fibers between the upstairs and downstairs brain so that the higher parts of the brain can more effectively communicate with and override the lower, more primitive impulses. We nickname these fibers connecting upper and lower brain areas the “staircase of the brain.” The staircase integrates upstairs and downstairs and benefits the region of the brain called the prefrontal cortex. This key area of the brain helps create the executive functions of self-regulation, including balancing our emotions, focusing our attention, controlling our impulses, and connecting us empathically with others. As the prefrontal cortex develops, children will be better able to put into practice the social and emotional skills we want them to develop and ultimately to master as they move through our home and out into the larger world.

To put it simply, integration in a relationship creates integration in the brain. An integrated relationship develops when we honor differences between ourselves and others, and then connect through compassionate communication. We empathize with another person, feeling their feelings and understanding their point of view. In this connection, we respect another person’s inner mental life but do not become the other person. This is how we remain differentiated individuals but also connect. Such integration creates harmony in a relationship. Amazingly, interpersonal integration can also be seen at the heart of how parent-child relationships cultivate integration in the child’s brain. This is how differentiated regions—like left and right, or up and down—remain unique and specialized but also become linked. Regulation in the brain depends upon the coordination and balance of various regions that emerge from integration. And such neural integration is the basis for executive functions, the capacity to regulate attention, emotions, thoughts, and behavior. That’s the secret of the sauce! Interpersonal integration cultivates internal neural integration!

So that’s the long-term benefit of connection: through relationships, it creates neural linkages and grows integrative fibers that literally change the brain and leave our kids more skilled at making good decisions, participating in relationships, and interacting successfully with their world.

So connection offers the short-term benefit of moving kids from reactivity to receptivity, and the long-term benefit of building the brain. The third benefit we want to highlight is a relational one: connection deepens the bond between you and your child.

Moments of conflict can be the most difficult and precarious times in any relationship. They can also be among the most important. Of course our kids know we’re there for them when we’re snuggling and reading a book together, or when we show up and cheer at their performances. But what about when tension and conflict arise? When we have incompatible desires or opinions? These moments are the real test. How we respond to our children when we’re not happy with their choices—with loving guidance? with irritation and criticism? with fury and a shaming outburst?—will impact the development of our relationship with them, and even their own sense of self.

It’s not always easy to even want to connect when our kids misbehave, or when they’re acting their ugliest and most out of control. Connecting might be the last thing in the world you want to do when a fight breaks out between your kids on a quiet airplane, or when they whine and complain about not getting a better treat after you’ve just taken them to the movies.

But connection should be our first response in virtually any disciplinary situation. Not only because it can help us deal with the problem in the short term. Not only because it will make our children better people in the long term. But also, and most important, because it helps us communicate how much we value the relationship. We know that our children have changing, changeable, and complex brains, and that they need us when they’re struggling. The more we respond with empathy, support, and listening, the better it will be for our relationship with them.

Tina recently attended a birthday party with her six-year-old at his friend Sabrina’s house. Her parents, Bassil and Kimberly, walked the guests out at the end of the party. When they returned to the living room of the house, they were met with a surprise. Here’s how Kimberly put it in an email to Tina:

After the party, Sabrina went into the house and opened all of her gifts unsupervised. So I couldn’t write down who gave her what. It was pandemonium! I managed to piece together most of the items because my daughter Sierra had been there when she opened them. Before Sabrina writes out the thank-you cards, I’d like to get this clarified. Did JP get her the kaleidoscope chalk? I’m sure Miss Manners would disapprove of my tactics, but I’d rather get it right than be nonspecific!

In this situation, we could certainly empathize with a tired parent for not handling herself well when she returned to the living room to find recently opened toys everywhere and torn wrapping paper littering the entire floor. After all, Kimberly had just hosted a fun but loud, entertaining but chaotic birthday party for fifteen six-year-olds and their parents and siblings. The circumstances were ripe for a parental meltdown, highlighted by lots of yelling about a spoiled kid who couldn’t even wait until the party was over before ripping into the presents like a wild animal tearing into meat.

By maintaining her own self-control, though, Kimberly was able to address the situation from a No-Drama, Whole-Brain frame of mind, which led her to begin with—you guessed it—connection. Rather than launching into a lecture or a tirade, she connected with her daughter. She first acknowledged how fun it was to have had the party, and now to get to open all of the presents. She even sat patiently as Sabrina showed her the set of fake moustaches she was so excited about. (You’d have to know Sabrina.) And then, once Kimberly had connected, she spoke with her daughter, teaching her what she wanted her to know about presents and waiting and thank-you notes. That’s how connection created an integrative opportunity, building a stronger brain and strengthening a relationship.

Will you be able to connect first every time your kids mess up or lose control of themselves? Of course not. We certainly don’t with our own kids. But the more frequently we can make connection our first response, regardless of what our children have done, or whether or not we ourselves are in the river of well-being, the more we’ll show our kids that they can count on us to offer solace, unconditional love, and support, even when they’ve acted in ways we don’t like. Talk about fortifying and deepening a relationship! What’s more, in strengthening your own relationship with your children, you’ll be better equipping them to be good siblings, friends, and partners as they move toward adulthood. You’ll be teaching by role modeling, guiding by what you do and not only by what you say. That’s the relational benefit of connection: it teaches kids what it means to be in a relationship and to love, even when we’re not happy with the choices made by the person we love.

When we teach parents about connecting and redirecting, one of the most common questions we hear is about tantrums. Usually someone in the audience will ask something like, “I thought we were supposed to ignore tantrums. Doesn’t connecting with a kid when he’s freaking out just give him attention? So doesn’t that just reinforce the negative behavior?”

Our response to this question reveals another place where the No-Drama, Whole-Brain philosophy deviates from conventional approaches. Yes, there may be times when a child throws what we might call a strategic tantrum, when he’s in control of himself and is willfully acting distressed to achieve a desired end: to get a toy he wants, to stay at the park longer, and so on. But with most children, and almost always with young children, strategic tantrums are much, much more the exception than the rule.

The vast majority of the time, a tantrum is evidence that a child’s downstairs brain has hijacked his upstairs brain and left him legitimately and honestly out of control. Or, even if the child isn’t fully dysregulated, he’s enough out of sorts in his nervous system that he whines or doesn’t have the capacity to be flexible and manage his feelings in that moment. And if a child is unable to regulate his emotions and actions, our response should be to offer help and emphasize comfort. We should be nurturing and empathic, and focus on connection. Whether he’s out of sorts and just beginning to move down the road to distress or so upset that he’s actually out of control, he needs us in this moment. We still need to set limits—we can’t let a child, in his distress, yank down the curtains at the restaurant—but our objective in that moment is to comfort him and help him calm down so he can regain control of himself. Recall that chaos and losing control are signs of blocked integration, where the different parts of the brain are not working as a coordinated whole. And since connection creates integrative opportunities, connection becomes the way we comfort. Integration creates the ability to regulate emotions—and that’s how we soothe our kids, helping them move from the chaos or rigidity of non-integrated states to the calmer and clearer harmony of integration and well-being.

So when parents ask for our opinion on tantrums, our response is that we need to completely reframe the way we think about the times our kids are the most upset and out of control. We suggest that parents view a tantrum not merely as an unpleasant experience they have to learn to get through, manage for their own benefit, or stop as soon as possible at all costs, but instead as a plea for help—as another opportunity to make a child feel safe and loved. It’s a chance to soothe distress, to be a haven when an internal storm is raging, to practice moving from a state of dis-integration into a state of integration, through connection. That’s why we call these moments of connection “integrative opportunities.” Remember that a child’s repeated experience of having her caregiver be emotionally responsive and attuned to her—connect with her—builds her brain’s ability to self-regulate and self-soothe over time, leading to more independence and resilience.

So a No-Drama response to a tantrum begins with parental empathy. When we understand why children have tantrums—that their young, developing brains are subject to becoming dis-integrated as their big emotions take over—then we’re going to offer a much more compassionate response when the screaming, yelling, and kicking begin. It doesn’t mean we’ll ever enjoy a child’s tantrum—if you do, you might consider seeking professional help—but viewing it with empathy and compassion will lead to much greater calm and connection than seeing it as evidence of the child simply being difficult or manipulative or naughty.

That’s why we’re not at all fans of the conventional approach that calls for parents to completely ignore a tantrum. We agree with the notion that a tantrum is not the time to explain to a child that she’s acting inappropriately. A child in the midst of a tantrum is not experiencing what is traditionally called a “teachable moment.” But the moment can be transformed through connection into an integrative opportunity. Parents tend to overtalk in general when their kids are upset, and asking questions and trying to teach a lesson mid-tantrum can further escalate their emotions. Their nervous systems are already overloaded, and the more we talk, the more we flood their systems with additional sensory input.

But that fact doesn’t at all logically lead to the conclusion that we should ignore our children when they’re distraught. In fact, we’re encouraging pretty much the opposite response. Ignoring a child in the midst of a tantrum is one of the worst things we can do, because when a child is that upset, he’s actually suffering. He is miserable. The stress hormone cortisol is pumping through his body and washing over his brain, and he feels completely out of control of his emotions and impulses, unable to calm himself or express what he needs. That’s suffering. And just like our kids need us to be with them and provide reassurance and comfort when they’re physically hurting, they need the same thing when they’re suffering emotionally. They need us to be calm and loving and nurturing. They need us to connect.

We know how unpleasant a tantrum can be. Believe us, we know. But here’s what it really comes down to. What message do you want to send your children?

When you deliver this second message, you’re not giving in. You’re not being permissive. It doesn’t mean you have to let a child harm himself, destroy things, or put others at risk. You can, and should, still set boundaries. You may even have to help him control his body or stop an impulse during a tantrum. (We’ll offer specific suggestions for doing so in the coming chapters.) But you set these limits while communicating your love and walking through the difficult moment with your child, always communicating, “I’m here.”

Of course we want the tantrum to resolve as quickly as possible, just like we want to get out of the dentist chair as soon as we can. It’s simply not pleasant. But if you’re working from a Whole-Brain perspective, the quickest ending to the tantrum is really not your primary goal. Rather, your first objective is to be emotionally responsive and present for your child. Your primary goal is to connect—which will offer all the short-term, long-term, and relational benefits we’ve been discussing. In other words, even though you want the tantrum to end as soon as possible, the larger goal of connecting actually gets you there a lot more efficiently in the short run, and achieves a whole lot more in the long run. You’ll make things easier and less dramatic for both your child and yourself by providing empathy and your calm presence during a tantrum, and you’ll build your child’s capacity to handle himself better in the future, because emotional responsiveness strengthens the integrative connections in his brain that allow him to make better choices, control his body and emotions, and think about others.

We’ve said that connection defuses conflict, builds a child’s brain, and strengthens the parent-child relationship. One question parents often raise, though, has to do with a potential drawback of connecting before redirecting: “If I’m always connecting when my kids do something wrong, won’t I spoil them? In other words, won’t that reinforce the behavior that I’m trying to change?”

These reasonable questions are based on a misunderstanding, so let’s take a few moments and discuss what spoiling is, and what it’s not. Then we can be more clear on why connecting during discipline is quite different from spoiling a child.

Let’s start with what spoiling is not. Spoiling is not about how much love and time and attention you give your kids. You can’t spoil your children by giving them too much of yourself. In the same way, you can’t spoil a baby by holding her too much or responding to her needs each time she expresses them. Parenting authorities at one time told parents not to pick up their babies too much for fear of spoiling them. We now know better. Responding to and soothing a child does not spoil her—but not responding to or soothing her creates a child who is insecurely attached and anxious. Nurturing your relationship with your child and giving her the consistent experiences that form the basis of her accurate belief that she’s entitled to your love and affection is exactly what we should be doing. In other words, we want to let our kids know that they can count on getting their needs met.

Spoiling, on the other hand, occurs when parents (or other caregivers) create their child’s world in such a way that the child feels a sense of entitlement about getting her way, about getting what she wants exactly when she wants it, and that everything should come easily to her and be done for her. We want our kids to expect that their needs can be understood and consistently met. But we don’t want our kids to expect that their desires and whims will always be met. (To paraphrase the Rolling Stones, we want our kids to know they’ll get what they need, even if they can’t always get what they want!) And connecting when a child is upset or out of control is about meeting that child’s needs, not giving in to what she wants.

The dictionary definition of “spoil” is “to ruin or do harm to the character or attitude by overindulgence or excessive praise.” Spoiling can of course occur when we give our kids too much stuff, spend too much money on them, or say yes all the time. But it also occurs when we give children the sense that the world and people around them will serve their whims.

Is the current generation of parents more likely to spoil their kids than previous generations? Quite possibly. We see this most commonly when parents shelter their children from having to struggle at all. They overprotect them from disappointments or difficulties. Parents often confuse indulgence, on one hand, with love and connection, on the other. If parents themselves were raised by parents who weren’t emotionally responsive and affectionate, they often experience a well-meaning desire to do things differently with their own kids. The problem appears when they indulge their children by giving them more and more stuff, and sheltering them from struggles and sadness, instead of lavishly offering what their kids really need, and what really matters—their love and connection and attention and time—as their children struggle and face the frustrations that life inevitably brings.

There’s a reason we worry about spoiling our kids by giving them too much stuff. When kids are given whatever they want all the time, they lose opportunities to build resilience and learn important life lessons: about delaying gratification, about having to work for something, about dealing with disappointment. Having a sense of entitlement, as opposed to an attitude of gratitude, can affect relationships in the future, when the entitled mind-set comes across to others.

We also want to give our children the gift of learning to work through difficult experiences. We’re doing our child no favor when we find his unfinished homework on the kitchen table and complete it ourselves before running it up to school to protect him from facing the natural consequences of a late assignment. Or when we call another parent to ask for an invitation to a birthday party that our child caught wind of but was not invited to. These responses create an expectation in children that they’ll experience a pain-free existence, and as a result, they may be unable to handle themselves when life doesn’t turn out as they anticipated.

Another problematic result of spoiling is that it chooses immediate gratification—for both child and parent—over what’s best for the child. Sometimes we overindulge or decide not to set a limit because it’s easier in the moment. Saying yes to that second or third treat of the day might be easier in the short term because it avoids a meltdown. But what about tomorrow? Will treats be expected then as well? Remember, the brain makes associations from all of our experiences. Spoiling ultimately makes life harder on us as parents because we’re constantly having to deal with the demands or the meltdowns that result when our kids don’t get what they’ve come to expect: that they’ll get their way all the time.

Spoiled children often grow up to be unhappy because people in the real world don’t respond to their every whim. They have a harder time appreciating the smaller joys and the triumph of creating their own world if others have always done it for them. True confidence and competence come not from succeeding at getting what we want, but from our actual accomplishments and achieving mastery of something on our own. Further, if a child hasn’t had practice dealing with the emotions that come with not getting what she wants and then adapting her attitude and comforting herself, it’s going to be quite difficult to do so later when disappointments get bigger. (In Chapter 6, by the way, we’ll discuss some strategies for dialing back the effects of spoiling if we’ve gotten into that unhelpful habit.)

What we’re saying is that parents are right to worry about spoiling their kids. Overindulgence is unhelpful for children, unhelpful for parents, and unhelpful for the relationship. But spoiling has nothing to do with connecting with your child when he’s upset or making bad choices. Remember, you can’t spoil a child by giving him too much emotional connection, attention, physical affection, or love. When our children need us, we need to be there for them.

Connection, in other words, isn’t about spoiling children, coddling them, or inhibiting their independence. When we call for connection, we’re not endorsing what’s become known as helicopter parenting, where parents hover over their children’s lives, shielding them from all struggle and sadness. Connection isn’t about rescuing kids from adversity. Connection is about walking through the hard times with our children and being there for them when they’re emotionally suffering, just like we would if they scraped their knee and were physically suffering. In doing so, we’re actually building independence, because when our children feel safe and connected, and when we’ve helped them build relational and emotional skills by disciplining from a Whole-Brain perspective, they’ll feel more and more ready to take on whatever life throws their way.

So yes, as we discipline our children, we want to connect with them emotionally and make sure they know we’re there for them when they’re having a hard time. But no, this doesn’t at all mean we should indulge their every whim. In fact, it would be not only indulgent but irresponsible if your child were crying and tantruming at the toy store because she didn’t want to leave, and you allowed her to keep screaming and throwing anything she could get her hands on.

You’re not doing a child any favors when you remove boundaries from her life. It doesn’t feel good to her (or to you or the other people in the toy store) to allow her emotional explosion to go unfettered. When we talk about connecting with a child who’s struggling to control herself, we don’t mean you allow her to behave however she chooses. You wouldn’t simply say “You seem upset” to a child as he hurls a Bart Simpson action figure toward a breakable Hello Kitty alarm clock. A more appropriate response would be to say something like, “I can see that you’re upset and you’re having a hard time stopping your body. I will help you.” You might need to gently pick him up or guide him outside as you continue to connect—using empathy and physical touch, remembering that he’s needing you—until he’s calm. Once he’s more in control of himself and in a state of mind that’s receptive to learning, then you can discuss what happened with him.

Notice the difference in the two responses. One (“You seem upset”) allows the child’s impulses to hold everyone captive, leaving him unaware of what the limits are, and doesn’t give him the experience of putting on the brakes when his desires are pressing the gas pedal. The other gives him practice at learning that there are limits on what he can and can’t do. Kids need to feel that we care about what they’re going through, but they also need us to provide rules and boundaries that allow them to know what’s expected in a given environment.

When Dan’s children were small he took them to a neighborhood park where he witnessed a four- or five-year-old boy being bossy and too rough with the children around him, some of them quite little. The boy’s mother chose not to intervene, ostensibly because she’d “rather not solve his problems for him.” Eventually another mom let her know that the boy was being rough and preventing children from using the slide, at which time his mother harshly reprimanded him from across the way: “Brian! Let those kids slide or we’re going home!” In response, he told her that she was stupid and began throwing sand. She said, “OK, we’re going,” and began gathering up their things, but he refused to leave. The mom kept making threats but took no action. When Dan left with his kids ten minutes later, the mom and her son were still there.

This situation raises a question about what we mean when we talk about connecting. In this case, the issue at hand wasn’t that the boy was upset and crying. He was still having a hard time regulating his impulses and handling the situation, but it was expressed more in stubborn and oppositional behavior. Still, connection was in order before his mother attempted to redirect him. When a child isn’t overwhelmed by emotions but is simply making less-than-optimal decisions, connection might mean acknowledging how he’s feeling in that moment. She could walk over and say, “It looks like you’re having fun deciding who gets to use the slide. Tell me more about what you and your friends are doing here.”

A simple statement like this, said in a tone that communicates interest and curiosity instead of judgment and anger, establishes an emotional connection between the two of them. The boy’s mother can then more credibly follow up with her redirection, which might express the same sentiment she used earlier, but do so in a very different tone. Depending on her own personality and her son’s temperament, she could say something like, “Hmmm. I just heard from another mom that some of the kids are wanting to use the slide, and that they’re not liking how you’re blocking it. The slide is for all the kids at the park. Do you have any ideas for how we can all share it?”

In a good moment, he might say something like, “I know! I’ll go down and then run around and they can go down while I’m climbing back up.” In a not-so-generous moment, he might refuse, at which time the mother might need to say, “If it’s too hard to use the slide in a way that works for you and your friends, then we’ll need to do something different, like throwing the Frisbee.”

With these types of statements, the mother would be attuning to his emotional state, while still enforcing boundaries that teach that we need to be considerate of others. She could even give him a second chance if need be. But if he then refused to comply and began hurling more insults and more sand, she would have to follow through on the redirection she promised: “I can see you’re really angry and disappointed about leaving the park. But we can’t stay because you’re having a hard time making good choices right now. Would you like to walk to the car? Or I can carry you there. It’s your choice.” Then she’d need to make it happen.

So yes, we want to always connect with our children emotionally.

But along with connecting, we must help kids make good choices and respect boundaries, as we clearly communicate and hold the limits. It’s what children need, and even what they want, ultimately. Again, they don’t feel good when their emotional states hold them and everyone else hostage. It leaves them on the chaos bank of the river, feeling out of control. We can help move their brains back toward a state of integration and move them back into the flow of the river by teaching them the rules that help them understand how the world and relationships work. Giving parental structure to our children’s emotional lives actually gives them a sense of security and the freedom to feel.

We want our kids to learn that relationships flourish with respect, nurturing, warmth, consideration, cooperation, and compromise. So we want to interact with them from a perspective that emphasizes both connections and boundary setting. In other words, when we consistently pay attention to their internal world while also holding to standards about their behavior, these are the lessons they’ll learn. From parental sensitivity and structure emerge a child’s resourcefulness, resilience, and relational ability.

Ultimately, then, kids need us to set boundaries and communicate our expectations. But the key here is that all discipline should begin by nurturing our children and attuning to their internal world, allowing them to know that they are seen, heard, and loved by their parents—even when they’ve done something wrong. When children feel seen, safe, and soothed, they feel secure and they thrive. This is how we can value our children’s minds while helping to shape and structure their behavior. We can help guide a behavioral change, teach a new skill, and impart an important way of approaching a problem, all while valuing a child’s mind beneath the behavior. This is how we discipline, how we teach, while nurturing a child’s sense of self and sense of connection to us. Then they’ll interact with the world around them based on these beliefs and with these social and emotional skills, because their brains will be wired to expect that their needs will be met and that they are unconditionally loved.

So the next time one of your children loses control or does something that drives you completely crazy, remind yourself that a child’s need to connect is greatest in times of high emotion. Yes, you’ll need to address the behavior, to redirect and teach the lessons. But first, reframe those big feelings and recognize them for what they are: a bid for connection. When your child is at his worst, that’s when he needs you the most. To connect is to share in your child’s experience, to be present with him, to walk through this difficult time with him. In doing so you help integrate his brain and offer him the emotional regulation he’s unable to access on his own. Then he can move back into the flow of the river of well-being. You will have helped him move from reactivity to receptivity, helped build his brain, and deepened and strengthened the relationship you two share.