Anna’s eleven-year-old, Paolo, called her from school and asked whether he could go home with his friend Harrison that afternoon. The plan, Paolo explained, was to walk to Harrison’s, where the boys would do homework, then play until dinner. When Anna asked whether Harrison’s parents were aware of the plan, Paolo assured her they were, so Anna told him she’d pick him up before dinner.

However, when Anna texted Harrison’s mother later that afternoon, telling her she’d be picking up Paolo in a few minutes, Harrison’s mother revealed that she was at work. Anna then learned that Harrison’s father hadn’t been home, either, and that neither of them knew of the boys’ plan for Paolo to come over.

Anna was mad. She knew there might have been some sort of miscommunication, but it really looked to her like Paolo had been dishonest. At best he had misunderstood the plan, in which case he should have let her know when he realized that Harrison’s parents wouldn’t be home and hadn’t been contacted. At worst he had outright lied to her.

Once she and Paolo were in the car on the way home from Harrison’s, she felt like launching into him, leveling consequences and angrily lecturing him about trust and responsibility.

But that’s not what she did.

Instead, she took a Whole-Brain approach. Since her son was older and he wasn’t in a reactive state of mind, the “connect” part of her approach simply entailed hugging him and asking whether he’d had a good time. Then she showed him the respect of communicating with him directly. She told him about her text with Harrison’s mother, then said simply, “I’m glad you and Harrison have so much fun together. But I have a question. I know you know how important trust is in our family, so I’m wondering what happened here.” She spoke in a calm tone, one that didn’t communicate harshness and instead expressed her lack of understanding and her curiosity about the situation.

This curiosity-based approach, where she began by giving her son the benefit of the doubt, helped Anna decrease the drama from the discipline situation. Even though she was angry, she avoided immediately jumping to the conclusion that the boys had purposely deceived their parents. As a result, Paolo could hear his mother’s question without feeling directly accused. Plus, her curiosity put the responsibility of accounting for himself squarely on Paolo’s own shoulders, so he had to think about his decision making, which gave his upstairs brain a little bit of exercise. Anna’s approach showed Paolo that she worked from the assumption that he would make good decisions most of the time, and that she was confused and surprised when it appeared that he hadn’t.

In this case, by the way, he hadn’t made good decisions. He explained to his mother that Harrison had thought his father would be home, but when the boys arrived, Harrison’s father wasn’t there. He acknowledged that he should have let her know right away, but he just hadn’t. “I know, Mom. I should’ve told you nobody else was home. Sorry.”

Then Anna could respond and move from connection to redirection, saying something like, “Yes, I’m glad you’re clear that you should have told me. Tell me more about why that didn’t happen.” But she knew she wanted her redirection to be about more than just addressing this one behavior. She rightly recognized this moment as another opportunity to build important personal and relational skills in her son, and to help him understand that his actions had made a little dent in her trust and deviated from their family agreement to always check in if plans change. That’s why, before she turned to redirection, she checked herself.

Have you seen that British poster from World War II that’s become so popular? The one that says, “Keep Calm and Carry On”? That’s not a bad mantra to have at the ready when your child goes ballistic—or before you do. Anna recognized the importance of keeping calm when she addressed her problem with Paolo’s behavior. Blowing up and yelling at her son wouldn’t have done anyone any good. In fact, it would have alienated Paolo and become a distraction from what was important here: using this disciplinary moment to address his behavior, and to teach.

We’ll discuss many redirection strategies below, looking at different ways to redirect children when they’ve made bad decisions or completely lost control of themselves. But before you decide on which redirection strategies to use as you redirect your kids toward using their upstairs brains, you should first do one thing: check yourself. Remember, just as it’s important to ask, “Is my child ready?” it’s also essential that you ask, “Am I ready?”

Imagine that you walk into your recently cleaned kitchen and find your four-year-old perched on the counter, an empty egg carton and a dozen broken shells by her side, stirring a sand bucket full of eggs. With her sand shovel! Or your twelve-year-old informs you, at 6:00 p.m. on Sunday, that his 3-D model of a cell is due the following morning. This despite the fact that he assured you that all his homework was done, then spent the afternoon playing basketball and video games with a friend.

In the middle of frustrating moments like these, the best thing you can do is to pause. Otherwise your reactive state of mind might lead you to begin yelling, or at least lecturing about the fact that a four-year-old (or twelve-year-old) ought to know better.

Instead, pause. Just pause. Allow yourself to take a breath. Avoid reacting, issuing consequences, or even lecturing in the heat of the moment.

We know it’s not easy, but remember: when your kids have messed up in some way, you want to redirect them back toward their upstairs brain. So it’s important to be in yours, too. When your three-year-old is throwing a tantrum, remember that she’s only a small child with a limited capacity to control her own emotions and body. Your job is to be the adult in the relationship and carry on as the parent, as a safe, calm haven in the emotional storm. How you respond to your child’s behavior will greatly impact how the whole scene unfolds. So before you redirect, check yourself and do your best to keep calm. That’s a pause that comes from the upstairs brain but also reinforces the strength of your upstairs brain. Plus, when you show abilities like this to your children, they’re more likely to learn such skills themselves.

Staying clear and calm during a pause is your first step.

Then remember to connect. It really is possible to be calm, loving, and nurturing while disciplining your child. And it’s so effective. Don’t underestimate how powerful a kind tone of voice can be as you initiate a conversation about the behavior you’re wanting to change. Remember that, ultimately, you’re trying to remain firm and consistent in your discipline while still interacting with your child in a way that communicates warmth, love, respect, and compassion. These two aspects of parenting can and should coexist. That was the balance Anna tried to strike as she spoke with Paolo.

As you’ve heard us affirm throughout the book, kids need boundaries, even when they’re upset. But we can hold the line while providing lots of empathy and validation of the desires and feelings behind our child’s behavior. You might say, “I know you really want another ice pop, but I’m not going to change my mind. It’s OK to cry and be sad and disappointed, though. And I’ll be right here to comfort you while you’re sad.”

And remember not to dismiss a child’s feelings. Instead, acknowledge the internal, subjective experience. When a child reacts strongly to a situation, especially when the reaction seems unwarranted and even ridiculous, the temptation for the parent is to say something like “You’re just tired” or “It’s not that big of a deal” or “Why are you so upset about this?” But statements like these minimize the child’s experience—her thoughts, feelings, and desires. It’s much more emotionally responsive and effective to listen, empathize, and really understand your child’s experience before you respond. Your child’s desire might seem absurd to you, but don’t forget that it’s very real to him, and you don’t want to disregard something that’s important to him.

So when it’s time to discipline, keep calm and connect. Then you can turn to your redirection strategies.

For the remainder of this chapter we’ll focus on what you may have been waiting for: specific, No-Drama redirection strategies you can take once you’ve connected with your children and want to redirect them back to their upstairs brain. To help organize the strategies, we’ve listed them as an acronym:

Reduce words

Embrace emotions

Describe, don’t preach

Involve your child in the discipline

Reframe a no into a conditional yes

Emphasize the positive

Creatively approach the situation

Teach mindsight tools

Before we get into specifics, let us be clear: this isn’t a list you need to memorize. These are simply categorized recommendations that the parents we’ve worked with over the years have found to be the most helpful. (We’ve included the list, by the way, in the Refrigerator Sheet at the back of the book.) As always, you should keep all of these various strategies as different approaches in your parental tool kit, picking and choosing the ones that make sense in various circumstances according to the temperament, age, and stage of your child, as well as your own parenting philosophy.

In disciplinary interactions, parents often feel the need to point out what their kids did wrong and highlight what needs to change next time. The kids, on the other hand, usually already know what they’ve done wrong, especially as they get older. The last thing they want (or, usually, need) is a long lecture about their mistakes.

We strongly suggest that when you redirect, you resist the urge to overtalk. Of course it’s important to address the issue and teach the lesson. But in doing so, keep it succinct. Regardless of the age of your children, long lectures aren’t likely to make them want to listen to you more. Instead, you’ll just be flooding them with more information and sensory input. As a result, they’ll often simply tune you out.

With younger children, who may not have learned yet what’s OK and what’s not, it’s even more important that we reduce our words. They often just don’t have the capacity to take in a long lecture. So instead, we need to reduce our words.

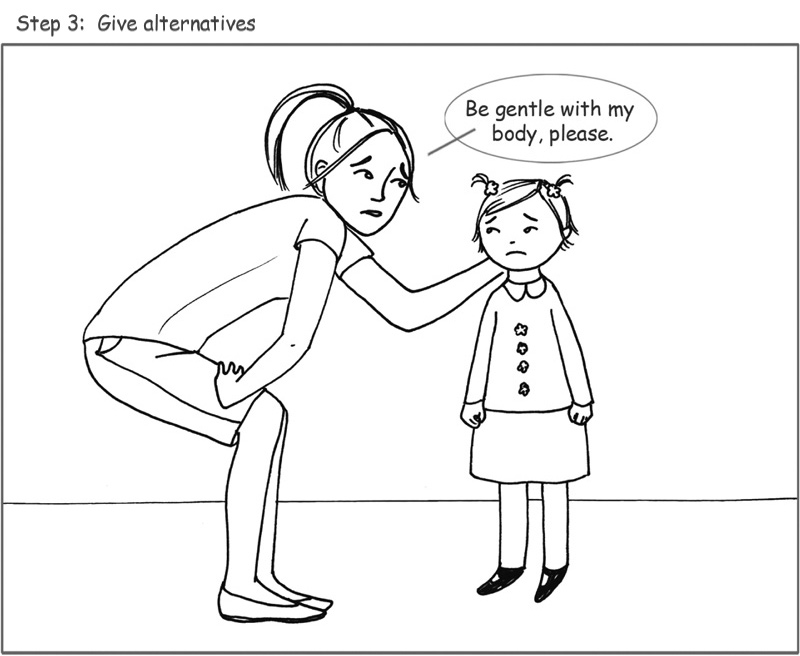

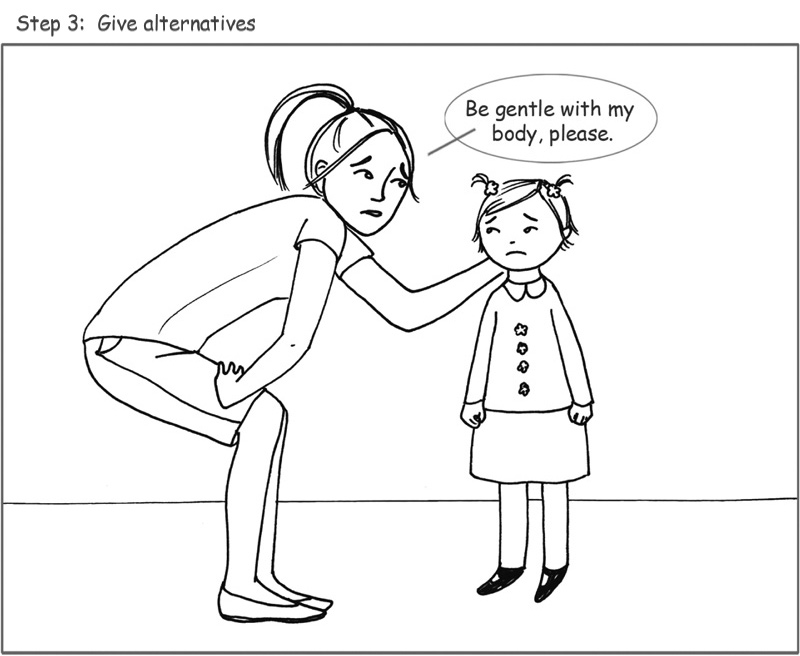

If your toddler, for instance, hits you because she’s angry that she doesn’t have your attention while you’re attending to your other child, there’s simply no reason to go off on a long, drawn-out oration about why hitting is a bad response to negative emotions. Instead, try this four-step approach that addresses the issue and then moves on, all without using more than a few words:

By addressing the child’s actions and then immediately moving on, we avoid giving too much attention to the negative behavior and instead quickly get back on the right track.

For younger and older kids both, avoid the temptation to talk too much when you discipline. If you do need to cover an issue more fully, try to do so by asking questions and then listening. As we’ll explain below, a collaborative discussion can lead to all kinds of important teaching and learning, and parents can accomplish their disciplinary goals without talking nearly as much as they typically do.

The basic idea here is akin to the concept of “saving your voice.” Politicians, businesspeople, community leaders, and anyone else who depends on effective communication to achieve their goals will tell you that often there are times when they strategically save their voice, holding back on how much they say. They don’t mean their literal voice, as if they’ll make their throats hoarse by talking so much. They mean they try to resist addressing the small points in a discussion or a voting meeting, so that their words will matter more when they want to address the really important issues.

It’s the same with our kids. If they hear us incessantly telling them what to do and what not to do, and then once we’ve made our point we keep making it over and over again, they will sooner or later (and probably sooner) stop listening. If, on the other hand, we save our voice and address what we really care about, then stop talking, the words we use will carry much greater weight.

Want your kids to listen to you better? Be brief. Once you address the behavior and the feelings behind the behavior, move on.

One of the best ways to address misbehavior is to help kids distinguish between their feelings and their actions. This strategy is related to the concept of connection, but we’re actually making a completely different point here.

When we say to embrace emotions, we mean that during redirection, parents need to help their kids understand that their feelings are neither good nor bad, neither valid nor invalid. They simply are. There’s nothing wrong with getting angry, being sad, or feeling so frustrated that you want to destroy something. But saying it’s OK to feel like destroying something doesn’t mean it’s OK to actually do it. In other words, it’s what we do as a result of our emotions that determines whether our behavior is OK or not OK.

So our message to our children should be, “You can feel whatever you feel, but you can’t always do whatever you want to do.” Another way to think about it is that we want to say yes to our kids’ desires, even when we need to say no to their behavior and redirect them toward appropriate action.

So we might say, “I know you want to take the shopping cart home. That would be really fun to play with. But it needs to stay here at the store so other shoppers can use it when they come.” Or we might say, “I totally get it that you feel like you hate your brother right now. I used to feel that way about my sister when I was a kid and was really mad at her. But yelling ‘I’m going to kill you!’ isn’t how we talk to each other. It’s perfectly fine to be mad, and you have every right to tell your brother about it. But let’s talk about other ways to express it.” Say yes to the feelings, even as you say no to the behavior.

When we don’t acknowledge and validate our kids’ feelings, or when we imply that their emotions should be turned off or are “no big deal” or “silly,” we communicate the message, “I’m not interested in your feelings, and you should not share them with me. You just stuff those feelings right on down.” Imagine how that impacts the relationship. Over time, our children will stop sharing their internal experiences with us! As a result, their overall emotional life will begin to constrict, leaving them less able to fully participate in meaningful relationships and interactions.

Even more problematic is that a child whose parents minimize or deny her feelings can begin to develop what can be called an “incoherent core self.” When she experiences intense sadness and frustration, but her mother responds with statements like “Relax” or “You’re fine,” the child will realize, if only at an unconscious level, that her internal response to a situation doesn’t match the external response from the person she trusts most. As parents, we want to offer what’s called a “contingent response,” which means that we attune our response to what our child is actually feeling, in a way that validates what’s happening in her mind. If a child experiences an event and the response from her caregiver is consistent with it—if it’s a match—then her internal experience will make sense to her, and she can understand herself, confidently name the internal experience, and communicate it to others. She’ll be developing and working from a “coherent core self.”

But what happens if that match isn’t there and her mother’s response is inconsistent with the daughter’s experience of the moment? One mismatch isn’t going to have long-lasting effects. But if over and over again when she gets upset she is told something like “Stop crying” or “Why are you so upset? Everyone else is having fun,” she’s going to begin to doubt her ability to accurately observe and comprehend what’s going on inside her. Her core self will be much more incoherent, leaving her confused, full of self-doubt, and disconnected from her emotions. As she grows into an adult, she may often feel that her very emotions are unjustified. She might doubt her subjective experience, and even have a hard time knowing what she wants or feels at times. So it really is crucial that we embrace our children’s emotions and offer a contingent response when they are upset or out of control.

One bonus to acknowledging our children’s feelings during redirection is that doing so can help kids more easily learn whatever lesson we’re wanting to teach. When we validate their emotions and acknowledge the way they are experiencing something—really seeing it through their eyes—that validation begins to calm and regulate their nervous system’s reactivity. And when they are in a regulated place, they have the capacity to handle themselves well, listen to us, and make good decisions. On the other hand, when we deny our kids’ feelings, minimize them, or try to distract our kids from them, we prime them to be easily dysregulated again, and to feel disconnected from us, which means they’ll operate in a heightened state of agitation and be much more likely to fall apart, or shut down emotionally, when things don’t go their way.

What’s more, if we’re saying no to their emotions, kids aren’t going to feel heard and respected. We want them to know that we’re here for them, that we’ll always listen to how they feel, and that they can come to us to discuss anything they’re worried about or dealing with. We don’t want to communicate that we’re here for them only when they’re happy or feeling positive emotions.

So in a disciplinary interaction, we embrace our kids’ emotions, and we teach them to do the same. We want them to believe at a deep level that even as we teach them about right and wrong behavior, their feelings and experiences will always be validated and honored. When kids feel this from their parents even during redirection, they’ll be much more apt to learn the lessons the parents are teaching, meaning that over time, the overall number of disciplinary moments will decrease.

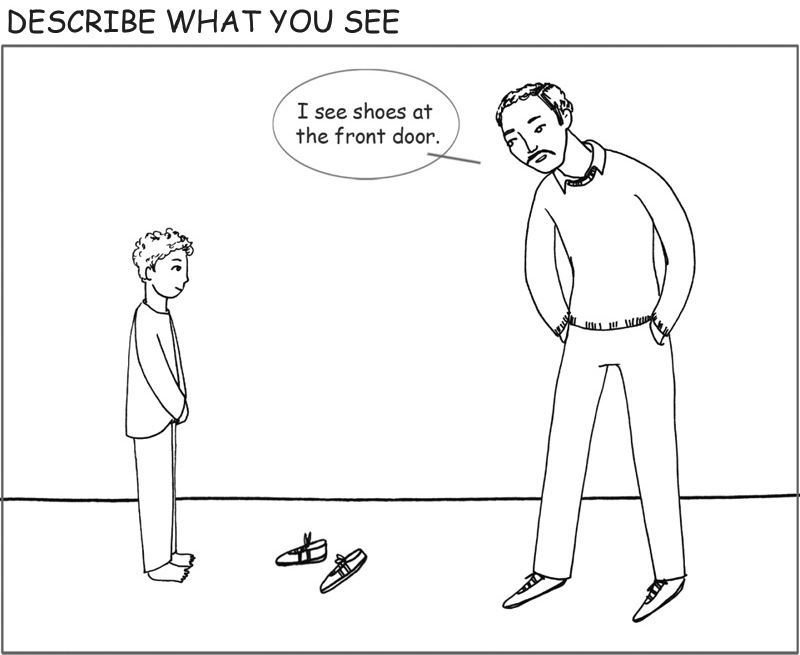

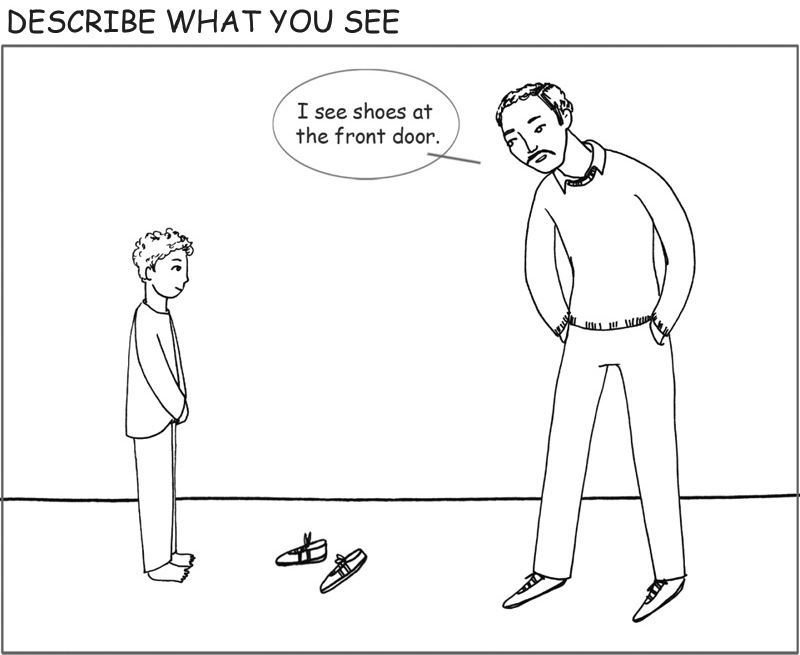

The natural tendency for many parents is to criticize and preach when our kids do something we don’t like. In most disciplinary situations, though, those responses simply aren’t necessary. Instead, we can simply describe what we’re seeing, and our kids will get what we’re saying just as clearly as they do when we yell and disparage and nitpick. And they’ll receive that message with much less defensiveness and drama.

With a toddler we might say something like, “Uh-oh, you’re throwing the cards. That makes it hard to play the game.” To an older child we can say, “I still see dishes on the table,” or “Those sound like some pretty mean words you’re using with your brother.” Simply by stating what we observe, we initiate a dialogue with our children that opens the door to cooperation and teaching much better than an immediate reprimand like “Stop talking to your brother that way.”

The reason is that even young children know wrong from right in most situations. You’ve already taught them what’s acceptable behavior and what’s not. Often, then, all you need to do is call attention to the behavior you’ve observed. This is essentially what Anna did when she said to Paolo, “I know you know how important trust is in our family, so I’m wondering what happened here.” Kids don’t need their parents to tell them not to make bad decisions. What they need is for their parents to redirect them, helping them recognize the bad decisions they’re making and what leads up to those decisions, so they can correct themselves and change whatever needs to be changed.

For all kids, and especially younger children and toddlers, you are of course teaching them good from bad, right from wrong. But again, a short, clear, direct message is going to be much more effective than a longer, overexplained one. And even with young children, a simple statement of observation will typically get your point across—and invite a response from them, either verbally or behaviorally.

The idea here isn’t that a description of what you see will be some sort of magical phrase that stops bad behavior in its tracks. We’re simply saying that parents should, as we put it in Chapter 5, “think about the how” and be intentional about how they say what needs to be said.

It’s not that the phrase “Looks like Johnny wants a turn on the swing” is communicating something fundamentally different from the phrase “You need to share.” But the former offers several distinct advantages over the latter. First, it avoids putting a child on the defensive. She might still feel the need to defend herself, but not to the same degree as if we were to reprimand her or tell her what she’s doing wrong.

Second, describing what we see puts the onus for deciding how to respond to the observation on the child, thus exercising his upstairs brain. That’s how we help him develop an internal compass, a skill that can last a lifetime. When we say, “Jake is feeling left out; you need to include him,” we are definitely getting our message across. But we’re doing all the work for our child, not allowing him to increase his inner skills of problem solving and empathy. If instead we simply say, “Look at Jake sitting over there while you and Leo play,” we give our child the opportunity to consider the situation for himself, and determine what needs to happen.

Third, describing what we see initiates a conversation, thereby implying that when our child does something we don’t like, our default response will be to visit with her about it, allow her to explain, and gain some insight. Then we can give her a chance to defend herself or apologize if necessary, and to come up with a solution to whatever problem her behavior might have caused.

“What’s going on?” “Can you help me understand?” “I can’t figure this out.” These can be powerful phrases when we’re teaching our kids. When we point out what we see, then ask our kids to help us understand, it opens up the opportunity for cooperation, dialogue, and growth.

Do you see how the two responses, even though their content isn’t all that different, would be apt to garner very different responses from the children, simply because of how the parents communicated their message? Once the parents describe what they’ve observed and ask for help in understanding, they can pause and allow the child’s brain to do its work. Then they can take an active role in their response.

This redirection strategy leads directly into the next one, which is all about making discipline a collaborative, mutual process, rather than a top-down imposition of parental will.

When it comes to communicating in a disciplinary moment, parents have traditionally done the talking (read: lecturing), and children have done the listening (read: ignoring). Parents have typically worked from an unexamined assumption that this one-directional, monologue-based approach is the best—and only viable—option to consider.

Many parents these days, however, are learning that discipline will be much more respectful—and, yes, effective—if they initiate a collaborative, reciprocal, bidirectional dialogue, rather than delivering a monologue.

We’re not saying that parents should forgo their roles as authority figures in the relationship. If you’ve read this far in the book, you know that we definitely don’t advocate that. But we do know that when children are involved in the process of discipline, they feel more respected, they buy into what the parents are promoting, and they are therefore more apt to cooperate and even help come up with solutions to the problems that created the need for discipline in the first place. As a result, parents and children work as a team to figure out how best to address disciplinary situations.

Remember our discussion of mindsight, and the importance of helping kids develop insight into their own actions and empathy for others? Once you’ve connected and your child is ready and receptive, you can simply initiate a dialogue that leads first toward insight (“I know you know the rule, so I’m wondering what was going on for you that led you to this”) and then toward empathy and integrative repair (“What do you think that was like for her, and how could you make things right?”).

For example, let’s say your eight-year-old becomes out-of-control furious because his sister is going on another playdate, and he feels like he “never gets to do anything!” In his anger, he throws your favorite sunglasses across the room and breaks them.

Once you’ve calmed down and connected with your son, how do you want to talk with him about his actions? The traditional approach is to offer a monologue where you say something like, “It’s OK to get mad—everyone does—but when you’re angry you still need to control your body. We don’t break other people’s things. The next time you’re that mad, you need to find an appropriate way to express your big feelings.”

Is there anything wrong with this communication style? No, not at all. In fact, it’s full of compassion and a healthy respect for your child and his emotions. But do you see how it’s based on top-down, one-directional communication? You are imparting the important information, and your child is receiving it.

What if, instead, you involved him in a collaborative dialogue that asked him to consider how best to address the situation? Maybe you would begin with the D from R-E-D-I-R-E-C-T and merely describe what you saw, then ask him to respond: “You got so mad a while ago. You grabbed my glasses and threw them. What was going on?”

Since you will have already connected, listened, and responded to his feelings about his sister’s playdate, he can now focus on your question. Most likely he’ll come back to his anger and say something like, “I was just so mad!”

Then you can simply describe, being intentional with your tone (since the how matters), what you saw: “Then you threw my glasses.” Here’s where you’re likely to get some sort of “Sorry, Mom.”

At this point you can move to the next phase of the conversation and focus explicitly on teaching: “We all get mad. There’s nothing wrong with getting angry. But what could you do the next time you’re that mad?” Maybe you could even smile and throw in some subtle humor he’d appreciate: “You know, besides destroying something?” And the conversation could go on from there, with you asking questions that help your young son think about issues like empathy, mutual respect, ethics, and handling big emotions.

Notice that the overall message remains the same, whether you offer a monologue or initiate a dialogue. But when you involve your child in the discipline, you give him the opportunity to think about his own actions, and whatever resulted from them, at a much deeper level.

You help him recruit more complex neural pathways that build mindsight capacities, and the result is deeper and longer-lasting learning.

Involving your kids in the discipline discussion is also a great way to dial back any patterns or behaviors that may have unintentionally been set up in your home. A one-directional, top-down discipline approach might lead you to storm into the living room and declare, “You’re spending way too much time on video games these days! From now on, no more than fifteen minutes a day.” You can imagine the response you might receive.

What if, instead, you waited until dinnertime, and once everyone was at the table, you said, “I know you’ve been getting to play video games a lot lately, but that’s not really working very well. It puts off homework, and I also want to make sure you’re spending time on other activities as well. So we need to come up with a new plan. Any ideas?”

You will probably still experience resistance when you broach the possibility of curtailing screen time. But you will have initiated a discussion about the issue, and when your kids know that you’re talking about cutting back, they’ll definitely be invested in being a part of the conversation to determine what limits will be set. You can remind them that you will be making the final decision, but let them see that you’re inviting their input because you respect them, want to consider their feelings and desires, and believe they are helpful problem solvers. Then, even if they don’t love the final call you make, they’ll know they were at least considered.

The same would go for any number of other issues: “I know we’ve been doing homework after dinner, but that’s not been working well, so we need a new plan. Any ideas?” Or “I’ve noticed that you’re not too happy about having to practice piano before school in the mornings. Is there a different time when you’d feel better about practicing? What would work for you?” Often they’ll come up with the same solution you would have imposed on the situation anyway. But they will have exercised their upstairs brain to do so and felt your respect along the way.

One of the best results from involving kids in the discipline process is that frequently they’ll come up with great new ideas for solving a problem, ideas you hadn’t even considered. Plus, you might be shocked to find out how much they are willing to bend to bring about a peaceful resolution to a standoff.

Tina tells the story of a time when her four-year-old absolutely had to have a treat—specifically, a bag of fruit snacks—at nine-thirty in the morning. She told him, “Those fruit snacks are delicious, aren’t they? You can have them after you have a good lunch in a little while.”

He didn’t like Tina’s plan and began to cry and complain and argue. She responded by saying, “It’s really hard to wait, isn’t it? You want the fruit snacks, and I want you to have a healthy lunch first. Hmmm. Do you have any ideas?”

She saw his little cognitive wheels turn for a few seconds, then his eyes got big with excitement. He called out, “I know! I can have one now and save the rest for after lunch!”

He felt empowered, the power struggle was averted, and Tina was able to give him an opportunity to solve a problem. And all it cost her was allowing him to have one fruit snack. Not such a big deal.

Again, there are of course times that you can’t give any wiggle room, and there may be times to allow your child to deal with a no or give him the opportunity to learn about waiting or handling disappointment. But usually when we involve the child in the discipline, it results in a win-win solution.

Even with very young children, we want to involve them as much as possible, asking them to reflect on their actions and consider how to avoid problems in the future: “Remember yesterday, when you got angry? You’re not usually someone who hits and kicks. What happened?” With questions like these, you give your child the opportunity to practice reflecting on her behavior and developing self-insight. Granted, you may not get great answers from a young child, but you’re laying the groundwork. The point is to let her think about her own actions.

Then you can ask her what she can do differently the next time she gets so mad. Discuss what she would like you to do to help her calm down. This type of conversation will deepen her understanding of the importance of regulating emotions, honoring relationships, planning ahead, expressing herself appropriately, and on and on. It will also communicate how important her input and ideas are to you. She’ll understand more and more that she’s an individual, separate from you, and that you are interested in her thoughts and feelings. Every time you involve your children in the process of discipline, you strengthen the parent-child bond, while also increasing the odds that they’ll handle themselves better in the future.

When you have to decline a request, it matters, once again, how you say no. An out-and-out no can be much harder to accept than a yes with conditions. No, especially if said in a harsh and dismissive tone, can automatically activate a reactive state in a child (or anyone). In the brain, reactivity can involve the impulse to fight, flee, freeze, or, in extreme cases, faint. In contrast, a supportive yes statement, even when not permitting a behavior, turns on the social engagement circuitry, making the brain receptive to what’s happening, making learning more likely, and promoting connections with others.

This strategy will differ according to the age of your children. To a toddler who is asking for more time at her grandmother’s when it’s time to leave, you can say, “Of course you can have more time with Nana. We need to go now, but Nana, would it be OK if we came back to your house this weekend?” The child may still have trouble accepting no, but you’re helping her see that even though she’s not getting exactly what she wants right now, she’ll be told yes again before too long. The key is that you’ve identified and empathized with a feeling (the desire to be with Nana) while creating structure and skill (acknowledging the need to leave now and delaying the gratification of the desire).

Or if your son can’t get enough of the Thomas the Tank Engine hands-on display at the local toy store and is unwilling to set down Percy the Engine so you can exit the store, you can offer him a conditional yes. Try something like, “I know! Let’s take Percy up to the saleswoman over there, and explain to her that you want her to hold him for you and keep him safe until we come back for story time on Tuesday.” The saleswoman will likely play along, and the whole potential fiasco can be avoided. What’s more, you’ll be teaching your child to develop a prospective mind, to sense the possibilities for the future and to imagine how to create future actions to meet present needs. These are executive functions that, when learned, can be skills that last a lifetime. You are offering guidance to literally grow the important prefrontal circuits of emotional and social intelligence.

Notice that this isn’t at all about protecting kids from being frustrated or providing them with everything they want. On the contrary, it’s about giving them practice at tolerating their disappointment when things inevitably don’t go their way. They aren’t attaining their desires in that moment, and you’re assisting them as they manage their disappointment. You’re helping them develop the resilience that will aid them every time they are told no throughout their lives. You’re expanding their window of tolerance for not getting their way and giving them practice at delaying gratification. These are all prefrontal functions that develop in your child as you parent with the brain in mind. Instead of discipline simply leading to a feeling of being shut down, now your child will know, from actual experiences with you, that the limits you set often lead toward learning skills and imagining future possibilities, not imprisonment and dismissal.

The strategy is effective for older children (and even adults) as well. None of us like to be simply told no when we want something, and depending on what else has been happening, a no may even push us over the edge. So instead of offering an outright refusal, we can say something like, “There’s a lot happening today and tomorrow, so yes, let’s invite your friend over, but let’s do it on Friday, when you’ll have more time with him.” That’s a lot easier to accept, and it gives a child practice in handling the disappointment, as well as in delaying gratification.

Say, for instance, a group of your nine-year-old’s friends are going to a concert to see the latest pop sensation, who, in your opinion, represents all the things you want your daughter not to emulate. Regardless of how you deliver the news, she’s not going to be happy to hear that she’s not going to the concert. But you can at least mitigate some of the drama by being proactive and getting ahead of the curve on the issue.

You might, for example, ask her about upcoming concerts she’d like to attend, and offer to take her and a friend to the movies in the meantime. If you want to go the extra mile, you could even get online and look for a different concert she’d be interested in attending in the near future. Pay close attention to your tone of voice. Particularly if you’re having to deny a child something she really wants, it’s important that you avoid coming across as patronizing or overly dogmatic in your opinion. Again, we’re not saying this strategy will make everything easy and keep your child from feeling angry, hurt, and misunderstood. But by coming up with some sort of conditional yes, rather than a simple “No, you’re not going,” you at least decrease the reactivity and show your child that you’re paying attention to her desires.

Granted, there are times we simply have to deliver the dreaded outright no. But it’s more often the case that we can find ways to avoid having to turn our kids down without at least finding some measure of a yes that we can also deliver. After all, the things kids want are often the things we want for them, too—just at a different time. They may want to read more stories, or play with their friends, or eat ice cream, or play on the computer. These are all activities we want them to enjoy at some point as well, so usually we can easily find an alternative time to make it happen.

In fact, there’s an important place for negotiation in parent-child interactions. This becomes more and more important as kids get older. When your ten-year-old wants to stay up a little later and you’ve said no, but then he points out that tomorrow is Saturday and he promises to sleep an hour later than usual, that’s a good time to at least rethink your position. Obviously, there are some non-negotiables: “Sorry, but you can’t put your baby sister in the dryer, even if you do line it with pillows.” But compromise isn’t a sign of weakness; it’s evidence of respect for your child and his desires. In addition, it gives him an opportunity for some pretty complex thinking, equipping him with important skills about considering not only what he wants, but also what others want, and then making good arguments based on that information. And it’s a lot more effective in the long run than just saying no without considering other alternatives.

Parents often forget that discipline doesn’t always have to be negative. Yes, it’s usually the case that we’re disciplining because something less than optimal has occurred; there’s a lesson that needs to be learned or a skill that needs to be developed. But one of the best ways to deal with misbehavior is to focus on the positive aspects of what your kids are doing.

For example, think about that bane of parental existence, whining. Who doesn’t get tired of hearing our kids shift to that droning, complaining, singsong tone of voice that makes us grit our teeth and want to cover our ears? Parents often respond by saying something like, “Stop whining!” Or maybe they’ll get creative and say, “Turn down the whine,” or “What’s that? I don’t speak whine. You’ll have to tell me in another language.”

We’re not saying these are the worst possible approaches. It’s a problem, though, when we resort to negative responses, because it gives all of our attention to the behavior we don’t want to see repeated.

Instead, what if we emphasized the positive? Instead of “No whining,” we could say something like, “I like it when you talk in your normal voice. Can you say that again?” Or be even more direct in teaching about effective communication: “Ask me again in your powerful, big-boy voice.”

The same idea goes for other disciplinary situations. Instead of focusing on what you don’t want (“Stop messing around and get ready, you’re going to be late for school!”), emphasize what you do want (“I need you to brush your teeth and find your backpack”). Rather than highlighting the negative behavior (“No bike ride until you try your green beans”), focus on the positive (“Have a few bites of the green beans, and we’ll hop on the bikes”).

There are plenty of other ways to emphasize the positive when you discipline. You may have heard the old suggestion to “catch” your kids behaving well and making good decisions. Anytime you see your older child, who’s usually so critical of her younger sister, giving her a compliment, point it out: “I love it when you’re encouraging like that.” Or if your sixth grader has had a hard time getting his homework in on time, and you notice that he’s making a special effort to work ahead on the report that’s due next week, affirm him: “You’re really working hard, aren’t you? Thanks for thinking ahead.” Or when your kids are laughing together rather than fighting, make a point of it: “You two are really having fun. I know you argue, too, but it’s great how much you enjoy each other.”

In emphasizing the positive, you give your focus and attention to the behaviors you want to see repeated. It’s a gentle way to also encourage those behaviors in the future without the interaction becoming about rewards or praise. Simply giving your attention to your child and stating what you see can be a positive experience unto itself.

We’re not saying you’re not going to have to address negative behaviors as well. Of course you are. But as much as possible, focus on the positive and allow your kids to understand, and to feel from you, that you notice and appreciate when they’re making good decisions and handling themselves well.

One of the best tools to keep ready in your parenting toolbox is creativity. As we’ve said time and again throughout the book, there’s no one-size-fits-all discipline technique to use in every situation. Instead, we’ve got to be willing and able to think on our feet and come up with different ways to handle whatever issue arises. As we put it in Chapter 5, parents need response flexibility, which allows us to pause and consider various responses to a situation, applying different approaches based on our own parenting style and each individual child’s temperament and needs.

When we exercise response flexibility, we use our prefrontal cortex, which is central to our upstairs brain and the skills of executive functions. Engaging this part of our brain during a disciplinary moment makes it far more likely that we’ll also be able to conjure up empathy, attuned communication, and even the ability to calm our own reactivity. If, on the other hand, we become inflexible and remain on the rigid bank of the river, we become much more reactive as parents and don’t handle ourselves as well. Ever had that kind of moment? We have, too. Our downstairs brain will take charge and run the show, allowing our reactive brain circuitry to take over. That’s why it’s so important that we strive for response flexibility and creativity, especially when our kids are out of control or making bad decisions. Then we can come up with creative and innovative ways to approach difficult situations.

For example, humor is a powerful tool when a child is upset. Especially with younger children, you can completely change the dynamics of an interaction simply by talking in a silly voice, falling down comically, or using some other form of slapstick. If you are six years old and furious with your father, it’s not as easy to stay mad at him if he’s just tripped over a toy in the living room and enacted the longest, most drawn-out fall to the ground you’ve ever seen. Likewise, leaving the park is a lot more fun if you get to chase Mom to the car while she cackles and screams in pretend fear. Being playful is a great way to break through a child’s bubble of high emotion, so you can then help him gain control of himself.

It applies to interactions with older kids, too; you just have to be more subtle, and willing to receive an eye roll or two. If your eleven-year-old is on the couch, less than inclined to join you and his younger siblings in a board game, you can shift the mood by playfully sitting on him. Again, this has to be done in a considerate way and fit with his personality and mood, but a playfully apologetic “Oh, I’m sorry. I didn’t see you there” can at least draw a pretend-frustrated “Daaaad” and, again, change the dynamics of the situation.

One reason this type of playfulness and humor can be effective with kids—and adults as well, by the way—is that the brain loves novelty. If you can introduce the brain to something it hasn’t seen before, something it didn’t expect, it will give that something its attention. This makes sense from an evolutionary perspective: something that’s different from what we usually see will pique our interest on a primitive and automatic level. After all, the brain’s first task is to appraise any situation for safety. Its attention immediately goes to whatever is unique, novel, unexpected, or different, so that it can assess whether the new element in its environment is safe or not. The appraisal centers of the brain ask, “Is this important? Do I need to pay attention here? Is this good or bad? Do I move toward it or away from it?” This attention to novelty is a key reason that humor and silliness can be so effective in a disciplinary moment. Also, a respectful sense of humor communicates the absence of threat, which allows our social engagement circuitry to engage, which in turn opens us up to connect with others. Creative responses to disciplinary situations prompt our kids’ brains to ask these questions, become more receptive, and give us their full attention.

Creativity comes in handy in all kinds of other ways, too. Let’s say your preschooler is using a word you don’t like. Maybe she’s saying things are “stupid.” You’ve tried ignoring it, but you keep hearing the word. You’ve tried rephrasing it with a more acceptable synonym—“You’re right, those swim goggles are just wacky, aren’t they?”—but she keeps saying the goggles are stupid.

If ignoring and re-languaging don’t turn out to be effective strategies, then instead of forbidding the word—you know how well that works—get creative. One gifted preschool director came up with an inspired way to address the use of the word. Anytime he heard a child say something was stupid, he would explain, in a matter-of-fact tone, that the word is really only meant to be used in a particular context: “ ‘Stupid’ is such a great word, isn’t it? But I’m afraid you’re using it wrong, my dear. You see, that’s a very particular word that’s really meant to be used only when talking to baby chickens. It’s sort of a farm word. Let’s come up with another term to use in this situation.”

There are plenty of ways to approach a situation like this. You might suggest devising a code word that means “stupid,” so that you two share a secret language that no one else understands. Maybe the new term could be “glooby” or some other fun word to say, or it could even be a hand signal you make up together. The point is that you find a way to creatively redirect your child toward behavior that will work better for everyone involved, and even give you a fun sense of connection.

Let’s acknowledge one thing, though: sometimes you don’t feel like being creative. It feels like it takes too much energy. Or maybe you’re not too happy with your kids because of the way they’re acting, so you’re not exactly thrilled with the idea of mustering the energy to help them shift their mood or see things in a new light. In other words, sometimes you just don’t want to be playful and fun. You want them to just get in the car seat without a song and dance! You want them to just put on their stinking shoes! You want them to just get their homework done, or turn off the video game, or stop fighting, or whatever!

We get it. Boy, do we get it.

However, compare the two options. The first is to be creative, which often demands more energy and goodwill than we can easily muster when we don’t like the way our kids are acting. Ugh.

The other option, though, is to continue to have to participate in whatever battle the discipline situation has created. Double ugh. Doesn’t it usually end up taking much more time and much more energy to engage in the battle? The fact is, we can often completely avoid the battle by simply taking just a few seconds to come up with an idea that’s fun and playful.

So the next time you see trouble coming with your kids, or if there is a particular issue that you typically end up battling over, think about your two options. Ask yourself: “Do I really want the drama that’s on the horizon?” If not, try playfulness. Be silly. Even if you don’t feel like it, muster up the energy to be creative. Sidestep the drama that sucks the life out of you and takes the fun out of your relationship with your child. We promise, this option is more fun for everyone.

The final redirection strategy we’ll discuss is perhaps the most revolutionary. You’ll recall that mindsight is all about seeing our own minds, as well as the minds of others, and promoting integration in our lives. Once kids begin to develop the personal insight that allows them to see and observe their own minds, they can then learn to use that insight to handle difficult situations.

We discussed this idea in detail in our previous book, The Whole-Brain Child, focusing on several Whole-Brain strategies parents can use to help their children integrate their brains and develop mindsight. As we’ve taught the fundamentals of that book to audiences of parents, therapists, and educators, we’ve further refined those ideas.

The overall point of this final redirection strategy is one that even small children can understand, although older kids can obviously grasp the message in more depth: You don’t have to get stuck in a negative experience. You don’t have to be a victim to external events, or internal emotions. You can use your mind to take charge of how you feel, and how you act.

We realize that this is an extraordinary promise to make. But we are enthusiastic about this approach because of how it has worked for so many people through the years. Parents really can teach their kids and themselves mindsight tools that will help them weather emotional storms and deal more effectively with difficult experiences, thus leading them to make better decisions and enjoy less chaos and drama when they are upset. We can help our children increasingly have a say in how they feel, and in how they look at the world. Not through some mysterious, mystical process available only to the gifted, but by using emerging knowledge about the brain and applying it in simple, logical, practical ways.

For example, you may have heard about the famous Stanford marshmallow experiment from the 1960s and 1970s. Young children were brought into a room one at a time, and a researcher invited them to sit down at a table. On the table was a marshmallow, and the researcher explained that he would leave the room for a few minutes. If the child resisted the temptation to eat the marshmallow while he was gone, he would give the child two marshmallows when he returned.

The results were predictably hilarious and adorable. Search online and you can view video of numerous replications of the study, which show children variously closing their eyes, covering their mouths, turning their back to the marshmallow, stroking it like a stuffed animal, slyly nibbling at the corners of the marshmallow, and so on. Some children even grab the sugary treat and eat it before the researcher can finish delivering the instructions.

Much has been written about this study and follow-up experiments focusing on children’s ability to delay gratification, demonstrate self-control, apply strategic reasoning, and so on. Researchers have found that kids who demonstrated the ability to wait longer before eating the marshmallow tended to have many improved life outcomes as they grew up, such as doing better in school, scoring higher on the SAT, and being more physically fit.

The application we want to highlight here is what a recent study revealed about how children could use mindsight tools to be more successful at delaying gratification. Researchers found that if they provided the kids with mental tools that gave them a perspective or strategy to assist in containing their impulse to eat the marshmallow—thus helping them manage their emotions and desires in that moment—the children were much more successful at demonstrating self-control. In fact, when the researchers taught the kids to imagine that it wasn’t an actual marshmallow in front of them, but instead only a picture of a marshmallow, they were able to wait much longer than the kids who weren’t given any strategies to help them wait! In other words, simply by using a simple mindsight tool, the children were able to more effectively manage their emotions, impulses, and actions.

You can do the same for your kids. If you’ve read The Whole-Brain Child, you know about the hand model of the brain. Here’s how we introduced it in a “Whole-Brain Kids” cartoon for parents to read to their children.

Dan recently received an email from a school principal about a new kindergarten student who was struggling. The child’s teacher had taught her class the hand model of the brain, and she saw immediate results:

Yesterday a teacher came to me very concerned about the behavior of a new kindergarten student. He had just come to our school, and he was crawling under tables and saying he hated everything. (He is living with a family member, as his mom is incarcerated, and now he’s had to leave a teacher he really liked.)

Today our teacher retaught Brain-in-the-Hand. This was new to him. He was under the table most of the time while she taught. Soon after, he motioned to her, showed the flipped lid with his hand, and, on his own, went to the cool-off spot for a long time. (He almost fell asleep.)

When he finally got up, he approached her while she was teaching, pointed to his hand/brain with his lid closed, and joined the group.

After a bit she complimented him for his participation, and he said, “I know. I told you.” And he pointed to his hand/brain with the lid closed.

It was a huge moment, and she and I celebrated for him that he must really have needed that language!

Later today I went in during choice time and played “restaurant” with him. At one point he took a single flower out of a vase and handed it to me. My heart melted. Yesterday his teacher was comparing him to a child who truly struggles. Today he’s seeking every opportunity to connect with us. I’m so thankful that we’re learning this.

What did this teacher do? She gave her student a mindsight tool. She helped him develop a strategy for understanding and expressing what was happening around and within him, so he could then make intentional choices about how to respond.

Another way to say it is that we want to help kids develop a dual mode of processing the events that occur in their lives. The first mode is all about teaching children to be aware of and simply sense their subjective experiences. In other words, when they’re dealing with something difficult, we don’t want them to deny that experience, or to squelch their emotions about it. We want them to talk about what’s going on as they describe their inner experience, communicating what they’re feeling and seeing in that moment. That’s the first mode of processing: to simply acknowledge and be present with the experience. This teacher, in other words, didn’t want this little boy to deny how he was feeling. His feeling was his experience, and this “experiencing mode” is all about simply sensing inner subjective experience as it is happening.

But also we want our kids to be able to observe what’s going on within them, and how the experience is impacting them. Brain studies reveal that we actually have two different circuits—an experiencing circuit and an observing circuit. They are different, but each is important, and integrating them means building both and then linking them. We want our kids to not only feel their feelings and sense their sensations, but also to be able to notice how their body feels, to be able to witness their own emotions. We want them to pay attention to their emotions (“I’m noticing that I’m feeling kind of sad,” or “My frustration isn’t grape-size right now; it’s like a watermelon!”). We want to teach them to survey themselves, and then problem-solve based on this awareness of their internal state.

That’s what this boy did. He both lived in his experience and observed it. This allowed him to own what was going on. He had the perspective to be able to observe his experience as he was experiencing it. He could bear witness to the unfolding of experience, not just be in the experience. And then he could narrate what had happened, using language to express to others and to himself an understanding of what was going on. Using the hand model as his tool, he surveyed himself and recognized that he had “flipped his lid,” and he took steps in response, thus changing his internal state. Then when he was back in control of his emotions, he rejoined the group.

We see kids and parents in our work who become stuck in an experience they’re dealing with. Of course they need to deal with what’s happened to them. But that’s only one mode of processing. They also need to look at and think about what’s going on. They need to use mindsight tools to become aware of and observe, almost like a reporter, what is happening. One way to explain it is that we want them to be the actor, experiencing the scene in the moment, but also to be the director, who watches more objectively and can, from outside the scene, be more insightful about what’s taking place on camera.

When we teach kids to be both actor and director—to embrace the experience and also to survey and observe what’s happening within themselves—we give them important tools that help them take charge of how they respond to situations they’re faced with. It allows them to say, “I hate tests! My heart is pounding, and I’m starting to freak out!” but then also to observe, “That’s not weird. I really want to do well on it. But I don’t have to freak out. I just need to skip that TV show tonight and put in some extra study time.”

Again, this is about teaching kids that they don’t have to be stuck in an experience. They can also be observers and therefore change agents. Let’s say, for example, that the child described above remains overly concerned about tomorrow’s test. He begins a cascade of worrying that takes him into a spiral of panic about the test and his semester grade, and what that might mean in terms of graduating with the right GPA to get into a good college.

This would be a great time for his parents to teach him that he can change his emotions and his thinking by moving his body, or simply by altering his physical posture. In The Whole-Brain Child, we call this particular mindsight tool the “move it or lose it” technique. The boy’s parents could have him sit “like a noodle,” completely relaxed and “floppy,” for a couple of minutes. They all could then observe together how his feelings, thoughts, and body began to feel different. (It really is amazing how effective this particular strategy can be when we’re tense.) Then they could go back and talk about the exam from an “unstuck place” where he could see that he had some options.

There are limitless ways you can teach your kids about the power of the mind. Explain the concept of shark music, and have a conversation about what experiences from the past might be impacting their decision making. Or explain the river of well-being. Show them the picture from Chapter 3, and walk them through a discussion of a recent experience when they were especially chaotic or rigid. Or when they are feeling scared about something, tell them, “Show me what your body looks like when you’re brave, and let’s see what that feels like.” Recent studies are suggesting that simply holding our bodies in various postures can actually shift our emotions, along with the way we view the world.

Opportunities to teach mindsight tools are everywhere. In the car, when your nine-year-old is upset about an important shot she missed in her basketball game, direct her attention to the splotches on your windshield. Say something like, “Each spot on the windshield is something that has happened or will happen this month. This one here is your basketball game. That’s real, and I know you’re upset. I’m glad you’re able to be aware of your feelings. But look at all the other splotches on the windshield. This one here is the party this weekend. You’re pretty excited about that, aren’t you? And that one next to it represents your math grade from yesterday. Remember how proud you felt?” Then continue the conversation, putting the missed shot into context with her other experiences.

The point of an exercise like this isn’t to tell your daughter not to worry about her basketball game. Not at all. We want to encourage our kids to feel their feelings, and to share them with us. The sensing mode that lets us experience directly is an important mode of processing. But along the way, we want to give them perspective and help them understand that they can focus their attention on other aspects of their reality. This comes from having our observing circuits well developed, too, not just our sensing circuits. It’s not a matter of one or the other. Both are important, and together they make a great team. That’s one way we can help our kids develop integration by differentiating and then linking their sensing and absorbing capacities. Having built both circuits, our kids can use their minds to think about things other than what’s upsetting them in a particular moment, and as a result, they see the world differently and feel better. When we teach our kids mindsight tools, we give them the gift of being able to regulate their emotions, rather than being ruled by them, so they don’t have to remain victims of their environment or their emotions.

The next time a discipline opportunity comes up in your house, introduce your kids to some mindsight tools. Or use one of the other redirection strategies we’ve presented here. You might have to try several different approaches. No one strategy will apply in every situation. But if you work from a No-Drama, Whole-Brain perspective that first connects, then redirects, you can more effectively achieve the primary goals of discipline: gaining cooperation in the moment and building your children’s brains so they can be kind and responsible people who enjoy successful relationships and meaningful lives.