There’s nothing … absolutely nothing …

half so much worth doing

as simply messing around in boats.

Kenneth Grahame

Building Noah’s Ark as depicted by a 17th century Flemish painter

The life-preserving ark is central to the story of the Flood in any telling and we have established that what the hero Atra-hasīs had to build was a giant coracle. Before the arrival of the Ark Tablet all we really knew about constructing an ark in ancient Mesopotamia came from the famous description in the eleventh tablet of the Gilgamesh Epic. Hard facts for the boat-builder have accordingly been all too sparse and we have had to wait until now for the vital statistics of shape, size and dimensions, as well as everything to do with the crucial matter of waterproofing. The information that has now become available could be turned into a printed set of specifications sufficient for any would-be ark-builder today.

It has been an adventure, struggling forward within the forest of wedges in this precious document, especially where the tablet is sorely damaged on the reverse, but it is remarkable how so much can be extracted from Atra-hasīs’s laconic accounts. Businesslike data comes in lines 6–33 and 57–8, which cover the various stages of the work in the order in which they were carried out. The information comes as a series of ‘reports’ from Atra-hasīs, submitted to Enki as the work progressed; it is now our chance to look over his shoulder.

| 6–9: | Overall design and size |

| 10–12: | Materials and their quantities for the hull |

| 13–14: | Fitting the internal framework |

| 15–17: | Setting up the deck and building the cabins |

| 18–20: | Calculating the bitumen needed for waterproofing |

| 21–5: | Loading the kilns and preparing the bitumen |

| 26–7: | Adding the temper to the mix |

| 28–9: | Bituminising of the interior |

| 30–33: | Caulking the exterior |

| 57–8: | Exterior finishing – sealing the outer coat |

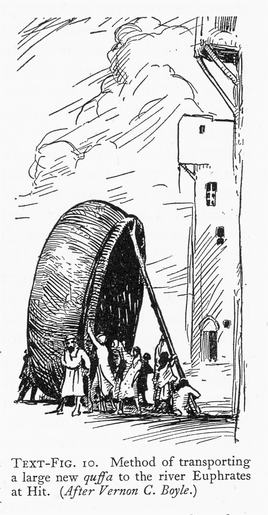

The cuneiform content we have to work with, leaving aside the difficulty of reading the broken lines, is put across in a very compact fashion and does not quite emerge as an easy ‘user’s manual’. We have to interpret each line as if we were coracle-builders ourselves, an approach thankfully made easier by the traditional method of building a Mesopotamian coracle having not changed since antiquity. We can see this from an informative description of constructing a contemporary Iraqi quffa published in the 1930s by the boat historian and expert James Hornell. Today such information would be irretrievable: the Iraqi coracle is extinct and the riverside makers and boatmen who once proliferated have vanished. Side by side with this precious account come late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photographs of Tigris coracle-builders at work employing the same techniques, which can also help the enquirer today.

Hornell’s coracle testimony has been utterly indispensable for this book; in fact it is hard to convey without headline phraseology exactly what it has contributed. There are several stages involved in coracle production and our boat historian has recorded these in full. With them as a guide it has been possible not just to read and translate the Akkadian description – as one would normally do – but to grasp what the cuneiform really means in terms of building a functional coracle. What is more, the content and measures of the cuneiform specifications are, amazingly, demonstrably based on realistic and practical data. Hornell’s description has both facilitated and confirmed interpretation of the construction technique, dimensions and order of procedure set out in the Ark Tablet.

The Ark Tablet, remember, with all this accumulated boat-building experience wrapped up in clay – was written the best part of four thousand years before Hornell recorded his own account.

The very oldest coracle-makers perfected a technique that was passed on for uncounted generations to follow, using the same locally available raw materials. Such a long history is inspiring, but not surprising, for there is every reason that the coracle – which can hardly be improved on as a practical design – should have remained unchanged in structure and use. But it is one thing to claim the likelihood of such longevity and quite another to be able to demonstrate it and, on top of that, benefit from it directly.

Writing this chapter, I might add, has been an assault course challenge for me. I have found it perfectly possible to get through life as a wedge-reader without being a boat person or functionally numerate, but both shortcomings were soon highlighted by having to deal with Atra-hasīs’s work problems. My one personal experience with boats occurred on holiday when I was about twelve, on a canal at Hythe, canoeing with my sister Angela. She was at the front; I had power and steering responsibilities from the back. Finding that we were dangerously close to the bank I swung my paddle up and over my sister’s head in order to correct our course, but, miscalculating substantially, thwacked her on the side of the head with the flat of the blade. This immediately knocked her unconscious; she slid down into the bottom of the canoe, understandably relinquishing her own paddle, which promptly drifted off behind us, while we somehow spurted forward out into mid-stream, later to be ignominiously rescued and resuscitated by adults in a passing rowing-boat. For me that was enough. As for mathematics, successive teachers suggested in school reports that I be sedated into oblivion before lessons. Until I learned about counting, right up to sixty, in cuneiform I always found this working horizon from Mary Norton comforting:

‘Your grandfather could count and write down the numbers up to – what was it, Pod?’

‘Fifty-seven,’ said Pod.

‘There,’ said Homily, ‘fifty-seven! And your father can count, as you know, Arrietty; he can count and write down the numbers, on and on, as far as it goes. How far does it go, Pod?’

‘Close on a thousand,’ said Pod.

The Borrowers, Vol. I

This Ark-building chapter is divided into two sections. The first explains the stages of the Ark Tablet’s building instructions in the light of the Hornell report, and makes full use of the results of the calculations, which are given in Appendix 3. The second investigates and compares the much less detailed account of the same activity in the eleventh tablet of the Gilgamesh Epic, with specific attention to disinterring the Old Babylonian tradition that lies behind it to throw light on how the present ‘classic’ text evolved. Appendix 3 thus covers all the technical matter, mensuration, procedures and calculations that are raised by this remarkable cuneiform document and that lead to the results presented in the first section. I could say that this section has been worked out and presented in partnership with my friend Mark Wilson but actually I just asked him a few stupid questions and this is the result. To admit that the methods were beyond me is unnecessary.

“Let her floor area be one ‘field’ [continued Enki],

“let her sides be one nindan (high).”

Ark Tablet: 9

In the Ark Tablet, we see that Enki has placed an order for a truly giant coracle. It works out to be the size of a Babylonian ‘field’, what we would call an acre, surrounded by high walls. In our terms, utilising all the evidence from Mesopotamian mathematical sources and terms of measurement, the coracle’s floor-area comes out at 3,600 m2. This is about half the size of a soccer pitch (roughly 7,000 m2), while the walls, at about six metres, would effectively inhibit an upright male giraffe from looking over at us.

Atra-hasīs’s coracle was to be made of rope, coiled into a gigantic basket. This rope was made of palm fibre, and vast quantities of it were going to be needed, as reflected in Enki’s mollifying remarks:

“You saw kannu ropes and ašlu ropes/rushes for [a coracle before!]

Let someone (else) twist the fronds and palm-fibre for you!

It will surely need 14,430 (sūtu)!”

Ark Tablet: 10–12

Here we turn without delay to James Hornell:

Hornell’s Section 1

In construction a quffa is just a huge lidless basket, strengthened within by innumerable ribs radiating from around the centre of the floor. The type of basketry employed is of that widely distributed kind termed coiled basketry. In this system the arrangement is that of a continuous and flattened spiral. Formed of a stout cylindrical core of parallel lengths of some fibrous material – grass or straw generally – bound by parcelling or whipping into a rope-like cylinder. By concentric coiling of this ‘filled rope’, the shape required is gradually built up. The parcelling consists of a narrow ribbon of strips split off from date-palm leaflets, wound in an open spiral around the core filling. As this proceeds the upper part of the coil immediately below is caught in by the lacing material being threaded through a hole made by a stout needle or other piercing instrument; this securely ties together the successive coils. The method is similar to that in use throughout Africa in the making of innumerable varieties of baskets and mats. The gunwale consists of a bundle of numerous withies, usually of willow, forming a stout cylindrical hoop attached to the uppermost and last-formed coil by closely set series of coir lashings.

Atra-hasīs’s kannu and ašlu in the Ark Tablet line 10 correspond to Hornell’s beaten palm-fibre and date-palm parcelling.

Consider the god Enki’s remarks, ‘developed’ a little:

You know about these coracles, surely, they’re everywhere …

Let someone else do the work; I know you have other things to do …

Why don’t I just tell you how much you are going to need and save you the trouble of working it out … ?

The raw material from which the rope is to be twisted and wrapped is palm fronds, for the Akkadian verb patālu means ‘to twist’, ‘to plait’, and the derived noun pitiltu denotes ‘palm fibre’. An unrelated Old Babylonian tablet from the city of Ur mentions no fewer than 186 labourers employed to make this kind of rope out of palm-fibre and palm-leaf. A century or so earlier a harassed bookkeeper totted up in another text ‘no less than 276 talents (8.28 tons) of palm-fibre rope … and 34 talents (1.02 tons) of palm-leaf rope’, raising the question as to what a shipyard would do with almost 10 tons of palm-fibre and palm-leaf rope of cord, as Dan Potts put it. To me this can only mean mass coracle production.

By Enki’s calculations they were going to need 14,430 sūtu measures of rope to coil the body of the Ark. This statement proves to be quite remarkable for two reasons. One is the actual way in which the total is recorded, the other the calculation that produces the total.

To me at least, 14,430 is a big number. It is written ‘4 × 3,600 + 30’ = 14,400 + 30. In other words four ‘3,600’ signs are used to make up the main total, followed by the sign for 30 and the same ‘3,600’ system quantifies the wooden stanchions in line 15 and the waterproofing bitumen in lines 21–2.

The number 3,600 is written with the old Sumerian ŠÁR sign and, as a number word, borrowed into Babylonian and pronounced šar. This ŠÁR is an important cuneiform sign. In shape and meaning it conveys enclosure and completeness, for originally it was a circle, so it was used to express ideas like ‘totality’ or the ‘entire inhabited world’ as well as the large number 3,600.

When it occurs in literary texts šár = 3,600 is conventionally understood as no more than a conveniently large round number. This is evident when a well-wisher writes in a letter, ‘may the Sun God for my sake keep you well for 3,600 years’, or a battle-flushed Assyrian king claims to have ‘blinded 4 × 3,600 survivors’. Assyriologists therefore often translate šár as ‘myriad’, as conveying the right sort of mythological size and feel, although of course the Greek decimal myriad literally means ‘10,000’, whereas Mesopotamians naturally thought in sixties, one ŠÁR being 60 × 60. What is truly surprising in the Ark Tablet calculations is that this sign 3,600 does not function just as a large round number but is to be taken literally.

To anyone familiar with Seven League Boots or the Hundred Acre Wood this statement, especially in a literary composition, will cause surprise, while any Assyriologist who knows the sign in texts such as the Sumerian King List or Gilgamesh XI will raise more than one quizzical eyebrow. Indeed, the conclusion takes a bit of swallowing, and it took a bit of swallowing for me too. All I can say is that, having finally deciphered Atra-hasīs’s big cuneiform numbers in the Ark Tablet, I had a strong hunch that they were not just fantasy totals and should at least be afforded the opportunity to speak for themselves. The principal reason for this was the added ‘+ 30’ after the 14,400. What was that? A joke? Enki putting over the equivalent of ‘a million and four?’ That interpretation, in context, seemed out of the question, leaving no other plausible conclusion than that the extra 30 was needed to reach a real total, meaning that the number totals had to be taken seriously. It was at that moment that things got alarming: a mathematician was needed, happily forthcoming in the person of Mark Wilson. The consequence was to establish and confirm that the numbers in Atra-hasīs’s work reports have to be taken seriously: real data and proper calculation have been injected into the Atra-hasīs story. Furthermore, the underlying Babylonian measurement, which is not mentioned in the text, has to be the sūtu, which we need to know in order to understand the numbers.

We can support this clearly with Enki’s calculation of the volume of necessary rope, having established:

1. Total surface area = coracle base + coracle walls + coracle roof. To sort this out, as I need hardly mention, requires a spot of Pappas’s Centroid Theorem, closely followed by a dose of Ramanujan’s Approximation.

2. The thickness of the rope. In the Ark Tablet we are not told about rope thickness, which suggests that it must be of a standard width for making coracles. A handful of old black and white photographs of Iraqi coracles are sufficiently in focus to suggest that traditional coracle rope was approximately of one finger thickness. As one ubānu, ‘finger’, was a standard Babylonian measure, we take this to be the thickness of Atra-hasīs’s rope. This choice will be confirmed in a later calculation concerning the thickness of the coracle’s bitumen coating.

The display of mathematical liveliness in Appendix 3 shows what has to be assayed to reach the result. Here we only need the answer, expressed in Babylonian sūtū measures:

| Enki’s rope volume estimate: | 14,430 sūtu. |

| Our rope volume calculation: | 14,624 sūtu. |

Enki’s calculation differs from ours by a smidgeon over 1 per cent. This is no accident or coincidence.

Just to be clear:

1. What might look like ‘myriad’ in the Ark Tablet, ŠÁR, means literally 3,600.

2. Enki is certainly thinking in terms of Babylonian sūtus.

3. The total length of one-finger-thickness rope needed to make Atra-hasīs’s Super Coracle works out at 527km. I repeat, five hundred and twenty-seven kilometres. A good way to think of that? It is approximately the distance from London to Edinburgh.

Enki imparts no further dimensions in the Ark Tablet. After his initial speech the narrative changes tack: it becomes an account by Atra-hasīs of what he himself has done, written in the first person.

Coiling the rope and weaving between the rows eventually produces a giant round floppy basket. The next job is to provide the whole with a stiffening framework of ribs. Hornell’s coracle building description continues:

The inner framework, giving strength and rigidity to the coiled walls of the quffa, is formed of a multitude of curved ribs, closely set; usually split branches of willow, poplar, tamarisk, juniper or pomegranate are employed; when these are not available the midribs of date-palm trees are used, but these are less esteemed. According to the size of the craft to be built, 8, 12 or 16 of these split branches are chosen of a length sufficient both to extend across the floor at its centre and also to pass up one side as a rib. These principal ‘frames’ are disposed in two series, one at right angles to the other. As half of those in each series pass down the side and across the bottom from opposite sides, their lower sections overlap and interdigitate, forming a strong double band across the floor; an equal number are similarly disposed at right angles to the first series, thereby giving two series of flooring or burden bands crossing one another on the floor. The quadrant spaces between these series of frames or main timbers are filled with very closely set ribs, bent, after soaking in warm water, to fit the concavely curved form of the walls of the quffa on the inside; sometimes the sharpness of the bend causes a splintering at the point where the side begins to turn inwards towards the gunwale. As the width of the quadrants bounded by the four series of frames widens with distance from the centre, the first-placed ribs are slightly longer than those on each side of them and those intercalated later are progressively slightly shorter, pair by pair. The lower ends are pointed in order to fit close together at the centre.

As each of these ribs and frames is placed in position, it is sewn with coir cord to the basketry walls. Two men are necessary for this operation, one inside the quffa to pass the cord through the wall of the basketry to his companion on the outside, who, in turn, threads it back to the inside, after hauling it taut. On the exterior the cord is seen passing obliquely upward from one seam to another; on the inside it passes horizontally over the rib from side to side and then emerges on the outside to repeat the oblique stitch to the seam above. On the inner side of the quffa the regularity of the series of horizontal stitches imparts an appearance of annulated ribbing that is characteristic and pleasing in its symmetry.

Atra-hasīs summarises this very succinctly.

“I set in place thirty ribs

Which were one parsiktu-vessel thick, ten rods long …

Ark Tablet: 13–14

The Babylonian word for rib is ṣēlu, and there are nice cases of it applied to boats, such as the entry in the bilingual dictionary which explains that Sumerian giš-ti-má = Babylonian ṣēl eleppi, ‘rib of a boat’, or the exorcistic incantation in which a demon ‘wrecks the ribs of the patient as if they were those of an old boat’. There must have always been old vessels beyond repair or waterproofing rotting in the mud by the rivers, not to mention carcasses of water buffalo or camels with their ribs exposed, white and gleaming. In the cuneiform the word is spelled ṣe-ri, with ‘r’ for ‘l’, but this does sometimes happen in Babylonian.

His ark-quality ribs, Atra-hasīs tells us, are as thick as a parsiktu and ten nindan long. This word parsiktu is not actually spelt out on the tablet but, as occurs in other tablets from southern Iraq, is written with an abbreviation, the sign PI. As one might say, ‘PI’ for parsiktu. In line 16 the whole word parsiktu, applied to the stanchions, has to be supplied by the reader, for the scribe abbreviates even further, writing ‘½’, to stand for ‘½ PI’.

The parsiktu is both a measuring vessel – a scoop – and a capacity measure. This is not surprising as many Mesopotamian metrological terms derive from vessel names. What is surprising is that a volume measure should be used to convey thickness. The vessel, we know, had a capacity of about sixty litres. Assuming it to be a box-shaped scoop with robust walls of about two fingers thickness we therefore arrive, as demonstrated in Appendix 3, at a parsiktu with an overall ‘thickness’ (width) of approximately one cubit or fifty centimetres.

Atra-hasīs, in response to Enki, is speaking colloquially and expressively. He declares that the boat ribs he produced were ‘as thick as a parsiktu’, much as we might say that something is ‘as thick as two short planks’ without knowing exactly how thick or short a plank might be, or whether there is even such a thing as uniformity in plank dimensions: everyone knows what you mean. At fifty centimetres across a parsiktu was close to a cubit thick, but Atra-hasīs avoids the word cubit for thickness even though he uses the nindan to define length. The point he wanted to put across was that these ribs were thicker than coracle ribs had ever been before. He was not a man, one might say, to be content with spare ribs.

Nota Bene: The expression ‘as thick as a parsiktu’ has no parallel in cuneiform literature beyond one perfectly extraordinary, extremely important and directly related case, which is discussed later in Chapter 12.

Each of Atra-hasīs’s coracle ribs is ten nindan long, which comes out at sixty metres, and about fifty centimetres thick. Once installed, each J-shaped rib ran down from the top of the coracle to the flat floor and out across the floor where, as Hornell describes, the ends form a kind of lattice, over and under. Once the main series of ribs is in place the remainder can be fitted in so that their ends will all lie interlocked together (or, as Hornell put it so magnificently, they will interdigitate), forming the floor itself, which achieves mat-like strength and solidity. Bitumen is then poured all over it.

Hornell mentions up to sixteen ribs for the normal coracle; the thirty set in by Atra-hasīs is modest for such a giant vessel and one can imagine that the framework would need to be supplemented by cross-bracing and other precautions.

Hornell lists the species of tree used by the Iraqi coracle-makers for these ribs, and they are all in fact attested in cuneiform inscriptions:

| Willow: | ḫilēpu – used for door panels and furniture; grows along rivers and canals. |

| Euphrates poplar: | ṣarbatu – the most common tree of lower Mesopotamia; wood cheap; used for inexpensive furniture and often as fuel; can however furnish logs (a letter request: ‘eleven times sixty poplars suitable for roofing’). |

| Tamarisk: | bīnu – a native and ubiquitous small tree or shrub; wood only for small objects (literary context: ‘You, Tamarisk, have a wood which is not in demand’). |

| Juniper: | burāšu – juniper proper used for wooden objects and furniture. |

| Pomegranate: | nurmû – there is no evidence for the use of pomegranate tree wood. |

Annoyingly, these types of wood do not seem to turn up in cuneiform boat texts, at least so far.

I set up 3,600 stanchions within her

Which were half (a parsiktu-vessel) thick, half a nindan high (lit. long)

Ark Tablet: 15–16

Here Atra-hasīs follows Enki in reckoning with the ŠÁR = 3,600. Stanchions at half a parsiktu by half a nindan were a crucial element in the Ark’s construction and an innovation in response to Atra-hasīs’s special requirements, for they allow the introduction of an upper deck. Very probably they were intended to be square in cross-section, with an area of about 15 × 15 fingers =225 fingers2. Assuming that Atra-hasīs’s ŠÁR, like Enki’s, meant that there were literally 3,600 stanchions, their combined area massed together would represent only about 6 per cent of the total 3,600 m2 floor space, a load-bearing distribution which is, so to speak, not unrealistic (see Appendix 3).

There is no need to visualise these stanchions in serried rows; on the contrary they could be placed in diverse arrangements, while, set flat on the interlocked square ends of the ribs, they would facilitate subdivision of the lower floor space into suitable ‘cabins’ and areas for bulky or fatally incompatible animals.

One striking peculiarity of Atra-hasīs’s reports is that he doesn’t mention either the deck or the roof explicitly, but within the specifications both deck and roof are implicit.

With regard to the deck, we can hardly doubt the implications of Atra-hasīs’s stanchions. This deck would come halfway up the sides, and, attached to the walls, would undoubtedly greatly strengthen the whole craft as well as enabling the fitting of the upper cabins. No conventional Iraqi coracle ever had a deck at all, needless to say, but, on the other hand, no other coracle had such a job to do.

Accommodation was needed for Atra-hasīs, his wife and immediate family, not to mention the other humans (discussed in the next chapter). There would be plenty of room upstairs for other life forms too; two conversational Babylonian parrots might cheer things up, for example.

Atra-hasīs says:

“I constructed her ḫinnu cabins above and below.”

Ark Tablet: 17

Although ‘cabin’ sounds anachronistic and cruise-like, the rare word ḫinnu means just that, as we are again informed by our ancient lexicographer:

giš.é-má = bīt eleppi, ‘wooden house on a boat’

giš.é-má-gur8, ‘wooden house on a makurru’.

(The same word occurs in a sophisticated symbolic dream described on a tablet from the time of Alexander the Great, in which the barque of the god Nabu is in a cult procession winding down a thoroughfare in Babylon and his cabin, ḫinnu, is quite clearly described.)

Captain A. Hasīs speaks of cabins in the plural, and the verb applied is rakāsu, ‘to tie’, or ‘to plait’, suggesting that they were at least partly made of reeds rather than wood. Atra-hasīs tells us that he installed them above and below, that is on the upper and lower decks. We might not stray far from the mark if we understand these cabins to resemble the small tied-reed houses in the southern marshes discussed in Chapter 6, especially those that are located within a round fence with animals mooching round about, floating gently.

We can be equally sure that the Ark had a roof. In line 45 Atra-hasīs goes up there to pray to the Moon God, and we know from the instructions in three parallel Flood accounts quoted in Chapter 7 that arks were to be roofed like the Apsû, suggesting a black circular shape consistent with Mesopotamian models of the cosmic Apsû, the waters under the earth. (Anyway, on a different level, without a roof the rain and sea would get in.) For the implications as to structure and material see Appendix 3.

The next stage is crucial: the application of bitumen for waterproofing, inside and out, a job to be taken very seriously considering the load and the likely weather conditions. The primary Akkadian word for bitumen is iṭṭû, which still survives in the modern name of Hít, the most famous of the natural sources of bitumen in Iraq now as then; it was known to Herodotus as Is. The old Sumerian name is ESIR. Bitumen comes bubbling out of the Mesopotamian ground for myriad uses as an unending, benevolent supply. For waterproofing a guffa it is unsurpassable, as we see in Hornell’s description.

After the structure of the quffa is complete, the outside is coated thickly with hot bitumen brought either from Hit on the Euphrates or from Imam Ali. This forms an efficient waterproofing. In addition, a thick layer of bitumen is spread over the floor to level it and to protect the floor lashings from damage. The inner surface of the sides is left bare. If the boatman or quffāji be superstitious, as often is the case, he will embed a few money cowries (Cypraea moneta) and some blue button beads in the bitumen on the outer side in the hope of thereby averting the evil eye … The life of a well-made quffa is long, for bitumen is an ideal preservative against rot, and when the coating cracks and begins to flake off, a fresh application makes the craft nearly as good as new.

There are in fact two Babylonian words for bitumen, iṭṭû, as mentioned, and kupru, both of which types are used by Atra-hasīs. The great bulk is kupru-bitumen, which is written with the Sumerian sign ESIR followed by the signs UD.DU.A (there are traces of signs left which I have restored in line 22, given the spacing in the gap), which mean something like ‘dried’. This is supplemented by a quantity of iṭṭû, written simply ESIR.

Atra-hasīs devotes twenty of his sixty lines to precise details about waterproofing his boat. It is just one of the many remarkable aspects of the Ark Tablet that we are thereby given the most complete account of caulking a boat to have come down to us from antiquity. The technical details behind these lines are to be considered carefully:

I apportioned one finger of bitumen for her outsides;

I apportioned one finger of bitumen for her interior;

I had (already) poured out one finger of bitumen for her cabins;

I caused the kilns to be loaded with 28,800 (sūtu) of kupru-bitumen

And I poured 3,600 (sūtu) of iṭṭû-bitumen within.

The iṭṭû-bitumen was not coming up to the surface (lit. to me);

(So) I added five fingers of lard,

I ordered the kilns to be loaded … in equal measure.

(With) tamarisk wood (?) (and) stalks (?)

I … (= completed the mixture(?)).

Ark Tablet: 18–27

First he works out the quantities of bitumen needed to waterproof all exterior and interior surfaces – including the cabins which he seems to have treated already – to a depth of one finger. Having calculated the amount required for the whole vast operation he is then seen doctoring the mixture in the kilns until it reaches the correct consistency for application. He tests it, perhaps with a dip-stick to gauge flow or viscosity, and finds that it is not yet perfect (line 23); he then adds equal quantities of lard and fresh bitumen to loosen it up. Eventually it is ready.

Here we have to understand the measure as the Sumerian ideogram ŠU.ŠI (usually written ŠU.SI), standing for the Babylonian ubānu, ‘finger’, one of which comes out at about 1.66 centimetres. Bitumen is thus applied to all ark surfaces to a depth of one finger.

The word kīru, ‘kiln’, occurs here in the plural but we do not know how many there were. Although bitumen as a staple commodity is often mentioned in cuneiform texts there is surprisingly little information about technical matters to help us. The Babylonian verb in line 21 is very often used of loading boats, but the bitumen here is not to be loaded aboard but put into the kilns to be heated up, so, ‘I ordered to be loaded’, refers in the Ark Tablet to the process of shovelling the raw material into the waiting kilns.

Atra-hasīs also tells us the quantity of bitumen that the waterproofing would involve, again expressed by the šár or 3,600 sign. The quantity of kupru-bitumen is 28,800 sūtu, written 8 × 3,600, which works out at 241.92 cubic metres. To this is added 3,600 sūtu, 30.24 cubic metres, of iṭṭû, ‘crude bitumen’, and five finger-thicknesses each of lard and fresh bitumen, whose volume cannot be worked out; the quantity of the latter two components need not have been considerable to make a difference to the whole. Nor do we know how many bitumen kilns there were running, or what their capacity was. We are told that a finger thickness of bitumen is needed inside and out. Our calculation involving the quantity of rope puts that bitumen total at eight šár, and the tablet confirms that we need eight šār of kupru plus a small amount of a more mastic quality applied separately for an external coat.

We get a glimpse of these operations in some scrappy records from a bitumen-supplier in the city of Larsa in about 1800 BC. The different types of boat-making bitumen shipped include: over fifteen gur of kupru for a 100-gur boat belonging to Æilli-Ishtar; two sūtu of iṭṭû for the kiln; iṭṭû for ‘talpittu’ of a wooden cabin; iṭṭû which has been poured into kupru; iṭṭû which has been poured into boat hulls; these and other supplies had been loaded onto a twenty-gur boat for delivery.

Some of this might have gone to coracle-builders. The little-known boat word talpittu, ‘smearing’, is used twice in this Larsa archive of a bitumen layer for wooden cabins. It derives from the Babylonian verb lapātu, ‘to touch’, and probably reflects the idea that bitumen was applied to a thickness of one finger (ubānu), as with the cabins that Atra-hasīs had to fit in his own giant model in line 20: ‘I had (already) poured out one finger of bitumen onto her cabins.’

We can assume that the bitumen layers were applied to the Ark long before everything and everybody was loaded on board. No one would be painting zoo cages with Babylonian creosote when all the livestock was in residence. If any part of that huge undertaking was described within the Flood Story we can learn nothing from the Ark Tablet, which is very badly damaged after the clear bitumen lines. The same is true of the corresponding part of Old Babylonian Atrahasis, while Gilgamesh XI dispenses with any description of such detail.

We learn from the Ark Tablet, however, that when everything was ready, and just before Atra-hasīs came aboard himself, another practical operation took place:

“I ordered several times (?) a one-finger (layer) of lard for the girmadû-roller,

Out of the thirty gur which the workmen had put to one side.”

Ark Tablet: 57–8

Nine cubic metres of lard in the hands of workmen is no simple matter of bread and dripping and this material can only be destined for physical application to the outer surface on a large scale. Such a large quantity will also have been prepared in advance, probably alongside the bitumen operation. Atra-hasīs tells us that a one-finger layer out of that supply must now be applied, using a roller called a girmadû (on which, see presently). Lard or oil applied as a final coating to a bitumen surface has a softening effect which enhances the level of waterproofing and this is undoubtedly what is going on here. It would only be necessary to oil the outside of the boat, of course, and so the process could be carried out at the last minute.

The remainder of the Ark Tablet concerns the continuation of the Flood Story plot: people and animals going aboard, last-minute deliveries and Atra-hasīs’s agony of mind, all of which we will look at in Chapter 10. Only selected parts of this great boat-building operation, described in such detail, were taken up into Gilgamesh XI, to which august narrative we now turn.

Work began on Utnapishti’s Ark as early as possible, and there was a good turnout:

At the very first light of dawn,

The population began assembling at Atra-hasīs’s gate.

Gilgamesh XI: 48–9

Immediately we perceive imported Old Babylonian narrative under this much later text. Utnapishti is reminiscing in the first person, so he ought to say ‘at my gate’. The Old Babylonian name of Atra-hasīs was there in the original but does not belong in the new text; it should have been edited out but has sneaked in under the wire. This single line is also a very important indication that the Old Babylonian text in the background was in the third person and not the first person, exactly as we can see it in Old Babylonian Atrahasis:

Atra-hasīs received the command,

He assembled the elders to his gate.

Old Babylonian Atrahasis: 38–9

It took five days before the ‘outer shape’ was ready. Unlike the Ark Tablet, which bypasses the episode, Old Babylonian Atrahasis (not much left) and Gilgamesh XI both list the workers who came to help with Atra-hasīs’s great project. We can see how well this labour force reflected the building of the giant coracle that we have been discussing:

| Worker | Project |

| The carpenter carrying his axe | Ribs, stanchions, plugs |

| The reed worker carrying his stone | Cabins |

| The young men bearing … | … |

| The old men bearing rope of palm-fibre | Boat structure |

| Rich man carrying bitumen | Waterproofing |

| Poor man carrying … ‘tackle’ | ‘Tackle’ |

One ancient contributor to the text added a specialist with an agasilikku axe, probably also for woodworking. The presence of ‘palm-fibre rope’, Akkadian pitiltu, is especially significant in view of what the god Ea says about the same fundamental material in Ark Tablet line 11 above.

The poor man’s ‘tackle’ (the word means ‘the needful things’) is a bit of a mystery. Utnapishti explains:

I struck the water pegs into her belly.

I found a punting-pole and put the tackle in place.

Gilgamesh XI: 64–5

Its safety importance had been stressed by the god Ea a millennium before:

The tackle should be very strong;

Let the bitumen be tough and so give (the boat) strength.

Old Babylonian Atrahasis: 32–3

The ‘punting pole’ in the Gilgamesh description, Akkadian parrisu, is essential for coracle navigation and its inclusion here is another pointer to the authentic riverine Old Babylonian background to the passage. The traditional Iraqi coracle made specific journeys to set destinations and required a paddle:

When small or moderate in size, the quffāji, leaning over one side (the functional fore end for the time being) propels his craft with a paddle. The usual system is to make several strokes first on one side and then on the other, changing over as necessary to keep a straight course. In medium-sized quffas two men paddle standing on opposite sides; the largest requires a crew of four paddlers … The paddle used to-day has a loom 5–6 feet in length, with a short blade, round or oblong, nailed to the outer end. It bears no resemblance to the ‘oars’ working on thole pins shown in Assyrian bas-reliefs of the quffas of Sennacherib’s period [see Pl.… ].

Hornell 1946: 104

Under flood conditions Atra-hasīs’s Ark had one job only: to stay afloat and safeguard its contents, but perhaps any giant coracle had to have its giant punting pole. The ‘tackle’ could therefore be the matching rowlock to keep the thing in place and stop it drifting away (as I know paddles are apt to do). The pole, if not for steering, might also help to prevent the vessel from spinning round and round, and we know from Tablet X that a character like Gilgamesh could handle thirty-metre parrisu poles by the three hundred when it came to it. The water pegs are also mentioned in Ark Tablet 47, and are sometimes thought to be bilge plugs.

The process of roofing the Round Ark with all its implications and associations reminded some early poet of the Apsû, the water under the world, and the idea is made explicit:

Cover her with a roof, like the Apsû.

Old Babylonian Atrahasis: 29; Gilgamesh XI: 705

Middle Babylonian Nippur, in contrast, says, ‘ … roof it over with a strong covering’, for talk there is of the non-round makurkurru ark, and the cosmic Apsû metaphor does not apply. Mention of the roof was not integral to every Old Babylonian version, however, for, as we have seen, the author behind the Ark Tablet omits the topic entirely, just as he makes no mention of installing a deck (although we can be sure there was one for reasons given above). A round Babylonian ark, then, had a lower deck or base and a deck above that, with cabins on both decks and a roof whose profile mirrored the base.

Utnapishti’s internal arrangements put this modest one-up, one-down structure to shame:

I gave her six decks

I divided her into seven parts

I divided her interior into nine.

Gilgamesh XI: 61–3

This is a flamboyant achievement, especially if, like so much else in this tablet, it ultimately derives from a far simpler Old Babylonian model.

When this narrative section is compared to the Ark Tablet (our only other source of information on these highly interesting matters), it is noticeable that the long and sticky bitumen passage with which we have just engaged is whittled down in Gilgamesh XI to two lines. Perhaps Assurbanipal’s editors experienced technical overload, and in any case the right way to bituminise a coracle didn’t have much to do with their narrative (which was really focused on Gilgamesh and what happened to him), and the symbolic nature of the structure far exceeded interest in how it was actually made.

While the matter of bitumen was substantially reduced in the Gilgamesh version, it is the same two principal types of bitumen that went into Utnapishti’s kiln. For these, and the oil that comes next, we are given the only Gilgamesh XI quantity measurements on offer, preserved partly in a tablet from Babylon as well as in the Nineveh copies:

I poured 3 × 3,600 [Nineveh, source W], or 6 × 3,600 [Babylon, source j] (sūtu) of kupru-bitumen into the kiln; [I poured] in 3 × 3,600 [Nineveh and Babylon](sūtu) of iṭṭû-bitumen …

Gilgamesh XI: 61–3

If we choose the 6 × 3,600 of the Babylon tradition over the Ninevite Assyrian 3 × 3,600 (as I much prefer to do) we find that Utnapishti put a total of nine šár of mixed bitumen into his kiln, with the idea of waterproofing – be it remembered – what was originally a round coracle boat of one-ikû area with one-nindan walls. This makes a suggestive point of comparison with the Old Babylonian Ark Tablet, which prepares a total of nine šár of bitumen for the identical purpose. This shows that the original bitumen number came through the process of textual transmission undistorted or unaltered, and that the quantity of bitumen was not altered to match the increased size. On the contrary, those responsible for the finished text of Gilgamesh XI reveal themselves to be aware that the original quantity of bitumen would only suffice to cover the lower two-thirds of the outside of the Ark in its Gilgamesh form (see below, and Appendix 3).

Utnapishti itemises his oil quantities as if accounting to someone rather defensively for expenses:

The workforce of porters was bringing over 3 × 3,600 (sūtu) of oil;

Apart from 3,600 (sūtu) of oil that niqqu used up

There were 3,600 × 2 (sūtu) that the shipwright stashed away.

Gilgamesh XI: 68–70

His oil came in three lots of 3,600; one was used for niqqu (the meaning of which is uncertain) and the remaining two went to Puzur-Enlil, shipwright and man-in-charge, who was to keep it until needed. No one is quite sure what niqqu means, although ‘libation’ has been suggested. The ‘apart from …’ idea derives from the Ark Tablet tradition, with a slight change from the original Babylonian meaning ‘out of’. Finally, we know that Ark Tablet 57 refers in this oily context to a tool called girmadû, here clearly spelled gi-ri-ma-de-e. This important term has also survived in Gilgamesh XI: 79, but scholars have usually thrown it out, emending the text. This rejection is now seen to be unjustified. Here is the crucial passage:

At sun-[rise to] I set my hand to oiling;

[Before] sundown the boat was finished.

[ …] were very difficult.

We kept moving the girmadû from back to front

[Until] two-thirds of it [were mar]ked off.

Gilgamesh XI: 76–80

The term ‘oiling’ in line 76 confirms the nature of the activity to which these five lines are devoted: it took all day and it wasn’t easy. Applying bitumen all over, inside and out, was a bigger job, but this final waterproofing attracted greater interest in the Gilgamesh version. Perhaps it was accompanied by some concluding ceremony. Puzur-Enlil’s supply of oil was applied with the girmadû, presumably by him. This word must mean ‘wooden roller’, exactly as described above by Chesney, for smoothing over the surface of the bitumen on a new boat once it was applied. The same roller would be used both for the bitumen, and then for the oily layer. Puzur-Enlil must have supervised both bitumen and oil sealing operations to have received such a handsome reward as this:

To the man who sealed the boat, the shipwright

Puzur-Enlil – said Utnapishti –

(variant: To the shipwright Puzur-Enlil in return for sealing the boat)

I gave the Palace with all its goods.

Gilgamesh XI: 95–6

This, to me, is an unforgettable, cinematographic image. Here the word ‘Palace’ is inserted, rather late in the proceedings, to show that Atra-hasīs has been king all along. At the last minute we meet Puzur-Enlil, who, one imagines, had been humouring Atra-hasīs and building his mad I-have-to-get-away-from-it-all boat without a murmur (but no doubt discussing it sardonically over a beer with his fellow workers). Now, as the hatch closes tight, momentous news! One pictures him running hysterically up the road to the Palace, bursting through the front door, ordering a banquet, half the cellar and as many of the harem as he could possibly manage. Later, sprawling and sated on the royal cushions, unable to move, he hears the first ping of raindrops on the roof over his head …

If Gilgamesh line 80 is correctly restored as ‘until two-thirds of it were marked off’, this means that the oil layer was only applied to the lower two-thirds of the boat’s exterior, which would correlate perfectly with the Nineveh issue of bitumen, for this only sufficed to coat the bottom two-thirds of Utnapishti’s Ark. They clearly anticipated little danger from leaks. Interestingly, modern coracles are often not bituminised up to the rim.

Up until now, it must be said, lines 76–80 in the Gilgamesh passage have been understood to describe the launching of Utnapishti’s Ark. Launching could hardly precede the loading of everything on board, and the apparently supportive interpretation, ‘poles for the slipway we kept moving back to front’, has depended on the unwarranted throwing out of the reading girmadû, which is now confirmed as a real word by the spelling in the Ark Tablet.

A launch with a bottle of fizz across the bows was never an option for the Babylonian flood hero or for his ark. The vast coracle would be ‘launched’ of its own accord as the waters arrived, like an abandoned lilo on the beach gradually taken up by an incoming tide.

How to launch a large coracle (if you have to).