The map of the world ceases to be a blank;

It becomes a picture

Full of the most varied and animated figures.

Each part assumes its proper dimensions.

Charles Darwin

In all the stories, as the floodwaters subsided, the Ark with its precious cargo landed safely on top of a mountain. Life on earth escaped by the skin of its teeth so the human and animal world could regroup and carry on as before with renewed vigour. Where the great craft actually landed, and what happened to it, only became important afterwards.

Different traditions grew up about the identity of the mountain, for the ancient Babylonian story always retained its importance within Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Earlier, in the cuneiform world, there had also been more than one tradition about it. As we have seen, our oldest versions of the Flood Story, including the Ark Tablet, come from the second millennium BC, but, most unhelpfully, no tablet from that period tells us anything about the Ark landing. To push things further we really need a contemporary Babylonian map.

Fortunately we have one.

The map in question is nothing less than a map of the whole world. It is one of the most remarkable cuneiform tablets ever discovered, so smart that it has its own Latin nickname – in the world of Assyriology at least – the mappa mundi, notwithstanding other claimants for the title. It is, in addition, the earliest known map of the world, drawn on a tablet of clay.

The Babylonian Map of the World, front view.

(picture acknowledgement 12.1)

The most important element is the drawing, which takes up the lower two-thirds of the obverse. It is a brilliantly accomplished piece of work. The known world is depicted from far above as a disc surrounded by a ring of water called marratu in Akkadian. Two concentric circles were drawn in with some cuneiform precursor of a pair of compasses whose point was actually inserted south of Babylon, perhaps at the city of Nippur, the ‘Bond of Heaven and Earth’. Within the circle the heartland of Mesopotamia is depicted in schematic form. The broad Euphrates River runs from top to bottom, originating in the northern mountainous areas and losing itself in canals and marshes in the south. The great river is straddled by Babylon, awesomely vast in comparison with other cities on the map, which are represented by circles, some inscribed in small cuneiform signs with their names. The locations of cities and tribal conglomerations are partly ‘accurate’ but by no means always so. The crucial components of the heartland are assembled within the circle, but this is no AA map for planning a motoring trip: the relative geographical proportions and relationships of the encircled features are far less important than the great ring of water that surrounds everything, while even further beyond is a ring of vast mountains that marks the rim of the world. These mountains are depicted as flat, projecting triangles; each is called a nagû. Originally they numbered eight.

The Babylonian Map of the World is justly famous and always on exhibition in the British Museum, but the surface of the clay is so delicate that it is has never been kiln-fired by the Museum’s Conservation Department, as is usually recommended to safeguard the long-term survival of cuneiform tablets. Now it is never even moved from its case or given on loan for exhibition. The reason for this is that when the tablet was on loan somewhere many years ago the nagû triangle in the lower left corner somehow became detached and, disastrously, lost.

When the mappa mundi was acquired by the British Museum in 1882 there were four triangles preserved, two complete and two with only the bottom section surviving. The tablet was first published in a sober German journal in 1889 and we have several other ink drawings and photographs that show the map at different times with the SW triangle still in position there, and these can be relied on as giving a faithful picture.

It must be said that damage or loss of this kind to our cuneiform tablets happens exceedingly rarely, and it is doubly unfortunate that it should have happened to a Map-of-the-World ‘triangle’, but it so turned out that I was able in a strange way to make up for this accident, with consequences for this book that I could never have anticipated. The British Museum excavations conducted in the Mesopotamian sites of Sippar and Babylon by the archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam in the later decades of the nineteenth century uncovered cuneiform inscriptions in quite staggering numbers. When they arrived in the Museum they were all registered by a cuneiform curator, who recorded basic details, allotted each a running number within its group, and housed each in a glass-topped box on the collection shelves. There was such a waterfall of incoming clay documents that the largest in a given consignment were naturally attended to at once, then all the good-sized pieces and so on. The tablets and fragments in each packing case often arrived wrapped in a twist of paper. Each consignment also included large quantities of small fragments – for Rassam’s workmen were, thank goodness, careful to collect every scrap of writing – but it often turned out that the curator in London had no chance to finish dealing with all the tiny pieces, some of which might contain only two or three signs of writing, before a fresh and important packing case arrived to claim his attention. The consequence was that over time a huge accumulation of small tablet fragments built up that would one day need to be dealt with. These fragments were often only a corner of a business document (‘Witnesses: Mr … ; Mr … ; Mr …’) or a flake from the surface (‘Day 1, Month 4, Darius year …’), which of themselves might not seem to hold much promise, but they are all treasure, for they all belong to and will ultimately join other pieces in the collection; in the end (probably after centuries of labour!) most of the cuneiform tablets in the British Museum will be completed and their inscriptions become fully readable. This entails a jigsaw puzzle of ungovernable proportions; all Assyriologists who work on our collection play this game and dream that one day the tantalising missing piece that they need so badly will turn up to be glued into place by a patient conservator. Sometimes it happens. Sometimes a mere scrap can turn out to be of the greatest significance.

For many years (as already confessed) I ran an evening class in cuneiform after hours in the British Museum. Once a week a loyal troupe of die-hards turned up to be initiated into the mystery of the wedges; we read all sorts of texts together and sometimes they even did a little homework. The class carried on for several years and by the time it reluctantly wound down one of the students, Miss Edith Horsley, had become a convinced cuneiform devotee and was anxious to continue as a volunteer in our Department. This seemed a good opportunity to have a crack at some of the long-ignored fragment collections. Miss Horsley was to unwrap and lightly clean the fragments from one of the chests, sort them as best she could and re-box them. After all those classes she certainly knew what a cuneiform business document looked like, so we agreed that she would distinguish corners, edges and body sherds, while anything that looked odd, or non business-like, should go in a special pile to be examined by me every Friday afternoon. On the whole these oddments turned out to be either pieces of school text in untidy writing or tabular lists of astronomical numbers, but one week on top of the pile was a scrap of inscribed clay with a triangle.

I have tried already to convey how life as a cuneiformist is full of adrenalin moments, but this was an extreme case. For I knew instantly, as any tablet person would, that this fragment with a triangle must join the mappa mundi. It had to. With trembling hands I picked up the fragment, put it in a little box, and rushed off to collect my keys to open the case in Room 51 and try it. But when I got downstairs the Map of the World tablet was, unbelievably, not in its place. I had forgotten in all the excitement that it was on exhibition elsewhere in the building as part of a historical display of maps put together by the British Library (who were then still on the Bloomsbury premises). It was an abominable wait until Monday morning. Then, at last, a librarian turnkey met me, a museum assistant and Miss Horsley to give us access so that we could test the join. Finally the locks opened. The triangle fragment fitted so snugly in the gap that it would not come out again.

This, however, is but the tip of the iceberg. The triangular nagû belonged right next to the long-known cuneiform label on the tablet that read: ‘Six Leagues in between where the sun is not seen.’ The new nagû was itself inscribed ‘Great Wall’. It could not be the Great Wall of China, of course, but an earlier big wall that was already known from cuneiform stories.

Making a join to the Map of the World was really something. I was perhaps a little preoccupied with this achievement and fell naturally into telling everybody within earshot about it, whether or not they were interested. A day or so later, queuing in the Museum Staff Canteen, I mentioned it to Patricia Morison, then editor of the British Museum Magazine, who immediately talked me into writing something. I had remarked to her blithely that this was just the sort of snippet that would come over well at the end of a day’s television news, when the broadcaster, struggling to dispel the gloom caused by the day’s events, likes to finish with such news as a pregnant cat being safely rescued from the top of a lighthouse by helicopter. It was nevertheless a very considerable shock the following morning to receive a telephone call from the front hall to say that Nick Glass and the Channel 4 news team had arrived to see me and Miss Horsley and the fragment. The magazine editor and he were neighbours, and she had apparently mentioned all this over the garden fence to him …

‘Have you ever lost a piece of a jigsaw puzzle down the back of the sofa?’ asked Trevor McDonald, wrapping up the 7 o’clock news the following evening. ‘Well, today in the British Museum …’

So, there was the whole story in full Technicolor, featuring our Mesopotamian Galleries, our Tablet Collection, our students at work in the Students’ Room, Miss Horsley surrounded by all her dusty fragments of tablet and, to top it all, wizard computer graphics (this was 1995) that showed the triangle fragment in blue jumping of its own accord into the empty space on the tablet. The whole report lasted four minutes and forty-two seconds. It was pure Andy Warhol. And it was my birthday. Little did I know it then, but that nagû join would have the most remarkable consequences for my subsequent Ark investigation …

The cuneiform handwriting dates the map to, most probably, the sixth century BC. The map’s content undoubtedly reflects Babylon as the centre of the world; the dot that can be seen in the middle of the oblong that is the capital city probably represents Nebuchadnezzar’s ziggurat. The tablet contains three distinct sections: a twelve-line description concerning creation of the world by Marduk, god of Babylon; the map drawing itself; and twenty-six lines of description that elucidate certain geographic features shown on the map.

These first twelve lines differ from the text on the reverse in spelling many words with Sumerian ideograms, and we can deduce that the scribe himself viewed this section as distinct from the map and its description from the double ruling across the width of the tablet that follows line 12. This ideographic style of spelling is fully in keeping with the first millennium BC date of the tablet itself, which is established by topographical terms in the map, in addition to the word marratu, as already mentioned. There were certainly eight nagûs originally. All are of the same size and shape, and where the tablet is still preserved we can see that the distance between them, travelling round parallel to the circular rim, varies between six and eight bēru or double hours, a measurement conventionally translated as ‘Leagues’.

The Babylonian Map of the World, back view.

(picture acknowledgement 12.2)

The whole of the reverse is given over to a description of these eight nagûs, stating that in each case it is the same seven-League distance across the water to reach them, and describing what is to be found on arrival. It is heart-breaking that such an interesting text is so broken, but as seasoned Assyriologists we are now resigned to the rule that the choicer the context the harder it will be to decipher.

While it has been argued that the map in its present form cannot be older than the ninth century BC – for this is the time when the word marratu is first used for sea, for example – in my opinion the conceptions behind the map and the description of the eight nagûs are much older, originating in the second millennium BC; in fact dating back to the Old Babylonian period in which the Ark Tablet was written. This can be concluded from the description’s very spellings, for the words are written in plain syllables in a style abhorred in first-millennium literary manuscripts, where ideograms, as found in the first twelve lines of this same tablet, are usually favoured. With this in mind we find ourselves with a cosmological system and tradition that is much older than the document on which it is written. The nature of the Map of the World tablet falls thereby into sharper focus: it represents an old tradition partly overlaid with later data or speculative ideas. The scribe at any rate tells us that his production is a copy from an older manuscript.

The world in the map is portrayed as a disc, and we can therefore assume that the world itself was generally visualised in the same way at the time when the map originated. The circular waterway marratu, which is written with the determinative for river, derives from the verb marāru, ‘to be bitter’. Since this word, although marked with the river sign, certainly means sea in other texts, we translate it here as ‘Ocean’, although ‘Bitter Sea’ or ‘Bitter River’ are equally possible. In eight directions, beyond that water, lie the nagûs. In the first millennium BC this word has a very practical meaning, used of regions or districts that are politically or geographically definable and literally within normal reach. In the mappa mundi, however, the meaning is quite different. These eight nagûs are giant mountains beyond the rim of the world which are unimaginably remote. Although necessarily depicted as triangles they must be understood as mountains whose tips would gradually appear above the horizon as they were approached across the Great Ocean.

In placing the mountainous nagûs in this position the cosmologists were answering with simplicity an unanswerable question: what lies beyond the horizon? It is rational to assume that there would eventually always be water, for all land known to man is fringed with water, but once across the marratu, what then? According to this system the world is hedged around by eight immense and unreachable mountains, which enclose the world like a fortress. Beyond that was the sky, or nothing, however you liked to look at it.

This geographical actuality is explicit in the tag at the end of the document, which refers to the Four Quarters of the World as the stage on which the eight-fold triangle descriptions play out. This grand expression, in Sumerian or Babylonian, had been favoured by the kings of Mesopotamia to express the breathtaking reach of their kingdoms since time immemorial. The understanding of the map in its original incarnation therefore is that all outlying geography is situated on the flat; travel outwards across the ocean ring and there the traveller will find these remote mountain land masses waiting with their curious occupants or larger-than-life features. On the other hand the triangles that ring the circular world could also be conceived to point up into the heavens, so that the map, drawn on the flat, represents a world like an eight-pointed crown.

In as much as they are decipherable the eight descriptions that accompany the nagûs read as if presented by a very bold traveller returned, passing on his discoveries and explaining as best he could what marvels could be expected by anyone who followed in his footsteps. The tone feels like a digest of heroic journeys and exotic traditions, reduced to a formula. Who might such a traveller be? Some Babylonian proto-Argonaut, sailing fearlessly across horizons in search of adventure and the unknown? A highly intrepid merchant, returning home full of wonderful tales and dining off them ever since? Or, might it not rather be some observer who could fly over the world beyond the ends of the earth? After all, the whole map is a bird’s-eye view, and the original compiler of this account, whoever he was, did have a dad called Bird, as we can see from the last line of the tablet.

Flying over the whole in English translation, nagû by nagû, we can encounter just a glimpse of the miraculous features far below.

Traces of an introductory line in very small writing

[To the first, to which you must travel seven Leagues, …]

… they carry (?) …

… great …

… within it …

Nagû II

[To the second], to which you must travel seven Leagu[es, … …]

…

Nagû III

[To the third], to which you must travel seven Leagu[es, …]

… [where] wingéd [bi]rds cannot fla[p their own wings …]

Nagû IV

[To the fo]urth, to which you must travel seven Lea[gues, …]

[The … ] … are as thick as a parsiktu-vessel; 10 fingers [thick its …]

Nagû V

[To the fift]h, to which you must travel seven Leagues, […].

[The Great Wall,] its height is 840 cubits; […].

[…] …, its trees up to 120 cubits; […].

[… by da]y he cannot see in front of himself […].

[… by night (?)] lying in … […].

[… you] must go another seven [Leagues …].

[… in the s]and (?) you must … […].

[…] … he will … […].

Nagû VI

[To the sixt]h, to which you must travel [seven Leagues, …].

[…] … […]

Nagû VII

[To the sevent]h, to which you must travel [seven Leagues, …].

… […] oxen with horns …];

They can run fast enough to catch wild [animals …].

Nagû VIII

To the [eight]h, to which you must travel seven Leagu[es, …];

Summary:

[These are the …] … of the Four Quarters, in every …

[…] … whose mystery no one can understand.

[…] … written and checked against the original,

[The scribe …], son of Bird, descendant of Ea-bel-ili.

The mountainous nagûs, as far as we can judge from the broken text, are thus each home to remarkable things; the third has (giant?) flightless birds; the fifth the 420-metre-high Great Wall which is labelled on the map itself, with forests of giant 60-metre trees; the sixth (giant?) oxen that can outrun and devour the wild beasts themselves. Unfortunately, due to damage the first, second and sixth nagûs can now tell us almost nothing.

Close-up of Babylonian Map of the World, front view, showing Urartu, the Ocean and Nagû IV, the original home of the Ark.

(picture acknowledgement 12.3)

It is the fourth nagû, however, which houses the greatest discovery. We can now understand, thanks to the Ark Tablet, that it is on that particular mountain, remote beyond the rim of the world, that the round Babylonian ark came to rest. These lines, compellingly, have to be read in the original:

[a-na re]-bi-i na-gu-ú a-šar tal-la-ku 7 KASKAL.GÍ[D …]

[To the fo]urth nagû, to which you must travel seven Leag[ues, …]

[šá GIŠ ku]d-du ik-bi-ru ma-la par-sik-tu4 10 ŠU.S[I …]

[Whose lo]gs (?) are as thick as a parsiktu-vessel; ten fingers [thick its …].

The first broken word in the second line, must, I think, be the uncommon Akkadian noun kuddu, ‘a piece of wood or reed, a log’. This is described as being ‘as thick as a parsiktu-vessel’, the same curious phrase that is applied to the giant coracle ribs in the Ark Tablet: ‘I set in place in thirty ribs, that were one parsiktu-vessel thick, ten nindan long.’ As discussed in Chapter 8, the comparison ‘thick as a parsiktu-vessel’, which expresses thickness in terms of volume, does not occur in other texts, and corresponds to our own ‘thick as two short planks’. The image must have remained permanently tied to Atra-hasīs’s Ark and have always been associated with it, and it here surfaces in the Map of the World in what is, to all intents and purposes, a quotation from the Old Babylonian story.

In the map inscription the equivalent ‘logs’ or ‘woodblocks’ is used, referring to the ‘ribs’. Each of Atra-hasīs’s coracle ribs is ten nindan long, which comes out at sixty metres, and about fifty centimetres thick. Where was Atra-hasīs’s carpenter to procure wood of this size in southern Babylonia? It might well be that the Map of the World answers this question too, for it tells us that trees of exactly the desired sixty-metre length grew in the adjacent Nagû V. Gilgamesh’s punting poles mentioned in Chapter 8 were a mere thirty metres in comparison. It looks as if ‘ten fingers [thick its …]’, takes the place of ‘ten nindan long’, and probably refers to the thickness of the bitumen coating (measured in fingers in Ark Tablet 18–22), with the number ‘bumped up’ as we have seen happen with other Ark numbers, for great lumps of bitumen might well have been scattered over a wide area.

As I understand it, the description of Nagû IV in the Map of the World describes the giant ancient ribs of the Ark. We can imagine Atra-hasīs’s great craft askew on top of that craggy peak, the bitumen peeling, the rope fabric long ago rotted away or eaten, and the arched wooden ribcage stark against the sky like a whitened, scavenged whale. The rare adventurer who makes it to the fourth nagû will see for himself the historic remains of the world’s most important boat.

This, then, is really something new. The oldest map in the world, safe and mute behind its museum wall of glass, tells us now where the Ark landed after the Flood! After 130 years of silence this crumbly, famous, much-discussed lump of clay divulges an item of information that has been sought after for millennia and still is!

But, there is more to be said. If it is established that the fourth nagû is the landing spot, can we identify on the map which of the eight nagûs is in fact number IV? The answer to this is, thankfully, in the affirmative.

The newly adhered nagû with the Great Wall as advertised on television allows us to do what has previously been impossible, namely to relate the eight mountains on the map to the eight descriptions on the back. The Horsley Triangle simply has to be the fifth nagû. How does it work? Observe the following ‘points’:

New readings coaxed out of the fragmentary description of Nagû V mean that this can now be safely identified with the ‘Great Wall’ nagû shown on the map. This is the one at the top pointing more or less north when the tablet is held in the normal reading position, and is the nagû shrouded in darkness.

From this fixture we can deduce that Nagû I is the completely lost nagû which once pointed due south.

We now have to decide whether the sequence I–VIII runs clockwise or anticlockwise in order to locate the other six nagûs correctly.

The triangle annotations in cuneiform were probably inscribed by the scribe on the tablet in an anticlockwise sequence. The legends will naturally have begun with the left nagûs, probably with west, because cuneiform writing runs from left to right, and proceeded triangle by triangle downwards, again because writing proceeds from top to bottom. The tablet will have been slightly rotated in a clockwise direction for each nagû so that the legend could be comfortably inscribed below the lower arm of each triangle. This process was followed throughout the eight, since the writing for the northeast nagû is upside-down for the reader.

I read the sequence therefore, anticlockwise, following the order of physical writing. This is not problematical; there are other Babylonian sky diagrams on tablets that run anticlockwise too. Given that, we conclude that Nagû IV, the Home for Lost Arks, is that which still survives on the map to the immediate right of the Great Wall Nagû V. With the help of the map we can now see how to get there.

The ark nagû can be reached most conveniently by travelling straight through the place called Urartu in the northeast of the Mesopotamian heartland – as it is depicted and named (Uraštu, in fact) on the map – and onwards in the same direction, crossing the marratu that encircled the world to the mountain that lay directly beyond at the very end of the world. This was the original conception of what happened to Atra-hasīs’s Ark. It had been carried by the floodwaters beyond the rim of the world, across the enclosing Ocean which must itself at that moment have been overwhelmed by the onrush, coming to rest on the fourth of the eight remote nagûs which were the furthest outposts of human imagination. And, except for heroes, unreachable. And anyone interested had first to get to Urartu.

(picture acknowledgement 12.5)

In a world where quiz shows love to provoke people into giving a knee-jerk answer that is then triumphantly condemned as wrong I suspect that Mount Ararat might often feature. It is a widespread belief that Noah’s Ark came to rest on ‘Mount Ararat’, the defence of the proposition being that it ‘says so in the Bible’. In a way it does, but with one important rider:

At the end of 150 days the waters had abated, and in the seventh month, on the seventeenth day of the month, the Ark came to rest on the mountains of Ararat. And the waters continued to abate until the tenth month; in the tenth month, on the first day of the month, the tops of the mountains were seen.

Genesis 8:3–5

The Hebrew text speaks of ‘mountains’ in the plural, so the key passage means ‘in the mountains of Ararat’, much as we would say, ‘in the Alps’. We cannot therefore really translate this as if it meant one particular mountain called ‘Mount Ararat’, but this understanding is very ancient and, as it turns out, represents a respectable tradition of its own. (Mt. Ararat is, incidentally, only the modern name. The venerable Armenian name is Massis; the equivalent Turkish name is Agri Dagh.)

The account in Genesis about the fate of the Ark came along, as discussed in the previous chapter, as part and parcel of the whole Flood Story, and there is every reason to assume that this matter too reflects Babylonian tradition. We can now see that, in broad terms, this is in fact the case. Biblical Ararat corresponds to the ancient name Urartu, which was the ancient political and geographical entity due north of the Mesopotamian heartland included in the Map of the World.

Judaeo-Christian tradition, following the Genesis passage, always identified Noah’s mountain with what is now called Mount Ararat, on the basis that it was a ‘huge mountain somewhere to the north’, in the area they knew to be called Ararat. Mount Ararat, located in northeastern Turkey near the borders with Iran and Armenia between the Aras and Murat rivers, is by far the highest mountain in the whole area. The mountain is a dormant volcano with two snowy peaks (the Greater Ararat and the Lesser Ararat). Mt. Ararat is, however, only the modern name. The venerable Armenian name is Massis; the equivalent Turkish name is Agri Dagh. To anyone who knew the story it would be the unmistakable location, easily the first that would have appeared above the waters, with ice-pack resources that could easily accommodate and preserve an ark. Everybody knew that the further north you went the more mountains there were, even if they had never been anywhere near them.

The Ark mountain denoted in the mappa mundi was not, however, the only Ark mountain that existed in the Mesopotamian world. An alternative comes with the classical authority of the seventh-century-BC Assyrian Gilgamesh story, the only surviving cuneiform flood account that refers to the manner in which Utnapishti’s Ark came to rest. I translate these lines as follows:

The flood plain was as flat as my roof;

I opened a vent and the sunlight fell on the side of my face;

I squatted down and stayed there, weeping;

Tears pouring down the side of my face.

I scanned the horizon in every direction:

In twelve [var. fourteen] places emerged a nagû.

On Mount Niṣir the boat ran aground.

Mount Niṣir held the boat fast and did not let it move.

One day, a second day, Mount Niṣir held the boat fast and did not let it move.

A third day, a fourth day, Mount Niṣir held the boat fast and did not let it move.

A fifth, a sixth, Mount Niṣir held the boat fast and did not let it move.

When the seventh day arrived …

Gilgamesh XI: 136–47

As the waters receded at least twelve, possibly fourteen nagûs became visible. This is the same specific term that we have encountered in the Map of the World, and here we are informed that they became visible as the floodwaters subsided. One particular nagû, at any rate, was called Mount Niṣir, and it was on this spot that Utnapishti’s Ark came securely to rest. The other eleven (or thirteen) are unnamed. The information here is given in the reverse order to the biblical tradition. Utnapishti sees and counts the mountain tops before his Ark comes to rest on one of them. When the bottom of Noah’s Ark caught fast (October 17th), the tips of no other mountains were yet visible and it took a further three months before the slowly descending waters could reveal them (January 1st).

The Gilgamesh nagû was originally called ‘Mount Nizir’ by George Smith in 1875, and this version of the name, or the form Niṣir, is still the one often encountered in books. The uncertainty as to the correct reading arises because the second cuneiform sign in the writing of the name (with which it is always spelt) can be read both -ṣir and -muš. It was not until 1986 that the alternative reading ‘Nimuš’ was seriously proposed, although I still prefer Mount Niṣir because this is the Mesopotamian name for the mountain and the Babylonian root behind it, naṣāru, ‘to guard, protect’, makes very good sense given the emphasis in this very Gilgamesh passage on how the mountain holds the Ark fast and will not let it move.

Mount Niṣir is an altogether different proposition to the Old Babylonian mountain of the mappa mundi. It was no remote, mythological conceit confined to the world of the poet or the wanderer, for the Assyrians knew exactly where it was, and so do we. Mount Niṣir is part of the Zagros mountain range, located in what is today Iraqi Kurdistan, near Suleimaniyah. An Assyrian exorcistic spell explicitly describes Mount Niṣir as ‘the mountain of Gutium’, the latter an old geographical term for the Zagros range. The mountain is mentioned by name in a very matter of fact manner as a landmark in the military annals of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) recounting a punitive campaign in the ancient kingdom of Zamua, formerly Lullubi. To an Assyrian, in other words, Mount Niṣir was just over the border.

This means that when Utnapishti looked out from his window and saw a dozen or more nagûs, of which Mount Niṣir was one, they were all inside the circle of the known world. The territory on which all those mountains stood to peek above the water lay within familiar, earthly geography. Here, accordingly, we witness at first-hand a drawing-in mechanism whereby the fabled, formerly unreachable icon is wound in like a fish until it is within desired range. The new location deprives the story of almost all of its ‘somewhere far beyond the most distant north’ quality. I cannot help but think that this prosaic attitude to the whole story correlates directly with the image of Utnapishti himself in Gilgamesh XI, careful to load his boat with gold and silver and a group of experts and only those animals that could be rounded up with the minimum of effort. We see here the Old Babylonian narrative diminished on all fronts.

Topographical evidence makes it certain that Mount Niṣir is to be identified with Pir Omar Gudrun, as has been shown especially by the scholar Ephraim Speiser, wandering through the terrain himself:

Ashurnasirpal starts from Kalzu early in the fall of 881 and, having passed Babite, directs his troops towards the Niṣir mountain. That mountain, ‘which the Lullu call Kinipa’, is the famous mount of the Deluge Tablet (141) on which the Flood-ship finds a resting place. The identification of Niṣir with Pir Omar Gudrun may be considered as absolutely certain. I have tried to indicate above how impressive the peak appears at close range. But its remarkably-shaped top, especially when snow-capped, also attracts the eye from a great distance. Often visible for more than a hundred miles, it was to the Babylonians the most natural place to perch their ark upon; the hub of the Universe has been placed at times in far less unusual spots.

Here is King Ashurnasirpal’s official ninth-century-BC account, translated out of his cuneiform annals:

On the fifteenth day of the month Tishri I moved on from the city Kalzi (and) entered the pass of the city Babitu. Moving on from the city Babitu I approached Mount Niṣir, which the Lullu call Mount Kiniba. I conquered the city Bunāši, their fortified city which (was ruled by) Muṣaṣina, (and) 30 cities in its environs. The troops were frightened (and) took to a rugged mountain. Ashurnasirpal, the hero, flew after them like a bird (and) piled up their corpses in Mount Niṣir. He slew 326 of their men-at-arms. He deprived him (Muṣaṣina) of his horses. The rest of them the ravines (and) torrents of the mountain swallowed. I conquered seven cities within Mount Niṣir, which they had established as their strongholds. I massacred them, carried off captives, possessions, oxen (and) sheep from them, (and) burnt the cities. I returned to my camp (and) spent the night. Moving on from this camp I marched to the cities in the plain of Mount Niṣir, which no one had ever seen. I conquered the city Larbusa, the fortified city which (was ruled by) Kirteara, (and) eight other cities in its environs. The troops were frightened (and) took to a difficult mountain. The mountain was as jagged as the point of a dagger. The king with his troops climbed up after them.

I threw down their corpses in the mountain, massacred 172 of their fighting men, (and) piled up many troops on the precipices of the mountain. I brought back captives, possessions, oxen, (and) sheep from them (and) burnt their cities. I hung their heads on trees of the mountain (and) and burnt their adolescent boys and girls. I returned to my camp (and) spent the night.

I tarried in this camp. 150 cities belonging to the cities of the Larbusu, Dūr-Lullumu, Bunisu, (and) Bāra – I massacred them, carried off captives from them, (and) razed, destroyed, (and) burnt their cities. I defeated 50 troops of the Bāra in a skirmish in the plain. At that time awe of the radiance of Aššur, my lord, overwhelmed all the kings of the land Zamua (and) they submitted to me. I received horses, silver, (and) gold. I put all the land under one authority (and) imposed upon them (tribute of) horses, silver, gold, barley, straw, (and) corvée.

In fact the literal Assyrian description of Mount Niṣir here is, ‘the mountain presented a cutting edge like the blade of a dagger’, which certainly matches the profile of Pir Omar Gudrun.

So what did those Assyrians think in the ninth century BC as they skirted the great mountain and gazed in awe at the jagged profile that hung remote above them? Had Gilgamesh and the Flood Story not been dinned into their youthful ears? Did not each man, from King Ashurnasirpal down, wonder whether the great boat was still there, and speculate on his chances of making it to the top to see? The king went up at least part of the way, but nothing is said anywhere about any arks.

In principle I find this strange, but perhaps they were all too busy, or maybe there had been Ark expeditions there long before. I do not believe that soldiers had no time for ‘fairytales’ or that the topic was simply never mentioned. If only one of them had written a letter home …

The appearance of Mount Niṣir in Gilgamesh XI exemplifies an important process within Ark history in general, for the Assyrian tradition must surely be a reaction against the much older Babylonian one, rejecting the ‘far beyond Urartu’ idea to reposition the Magic Mountain much nearer home. It is now in a far more convenient mountainous range, the Zagros. In the first millennium BC this area was usually under Assyrian control and thus safe and accessible, but at the same time conveniently ‘other’ to some extent. But the fact is, any Assyrian with a rope and a packet of sandwiches could go Ark-hunting in the secure knowledge that he had the right mountain.

The Assyrians certainly picked a very suitable-looking mountain for the purpose. What is beyond our knowing is when this revised tradition first took root, and, perhaps, what provoked the change. Ashurnasirpal gives both the Assyrian, Niṣir, and the local name, Kinipa, for the mountain in his account, possibly reflecting care to establish that Mount Niṣir was the mountain. In addition – although this is a bit of a long shot – the mention of Mount Niṣir four times in the Gilgamesh XI passage might also be significant. While the repetition might simply be a hangover from a rather heavy-handed oral technique, it seems equally possible on re-reading that it was designed to establish clearly which the mountain in question was – whatever other people might have said – and to use the authority of the classical text to guarantee its identification.

One day an Old Babylonian tablet with the Ark-landing episode will come to light. If that mountain turns out to be called Mount Niṣir, like in Assyria, I will need to buy an edible hat.

While the story of Nuh and the Flood within Islam is strongly connected with the biblical tradition, there was a divergence in tradition with regard to the mountain.

Then it was said, ‘Earth, swallow up your water, and sky, hold back,’ and the water subsided, the command was fulfilled. The Ark settled on Mount Judi …

Sura 11:44

Cudi Dagh (pronounced Judi Dah) is located in southern Turkey near the Syrian and Iraqi borders at the headwaters of the River Tigris, just east of the present Turkish city of Cizre (Jazirat ibn Umar). It is a good two hundred miles south of Mt Ararat and represents in every way an alternative Ark Mountain.

Certain Islamic authorities fill out the picture of this mountain:

The ark stood on the mount el-Judi. El-Judi is a a mountain in the country Masur, and extends to Jezirah ibn ’Omar which belongs to the territory of el-Mausil. This mountain is eight farasangs from the Tigris. The place where the ship stopped, which is on top of this mountain, is still to be seen.

Al-Mas’udi (869–956)

Al-Mas’udi also says that the Ark began its voyage at Kufa in central Iraq and sailed to Mecca, circling the Kaaba before finally travelling to Mount Judi where it settled.

Ibn Haukal (travelling 943–69)

Joudi is a mountain near Nisibin. It is said that the Ark of Noah (to whom be peace!) rested on the summit of this mountain. At the foot of it there is a village called Themabin; and they say that the companions of Noah descended here from the ark, and built this village.

Ibn al-’Amid or Elmacin (1223–74)

Heraclius departed thence into the region of Themanin (which Noah – may God give him peace! – built after he came forth from the Ark). In order to see the place where the Ark landed, he climbed Mount Judi, which overlooks all the lands thereabout, for it is exceedingly high.

Zakariya al-Qazwini (1203–83)

This last writer records that there was still, at the time of the Abbasids, a temple on Mount Judi which was said to have been constructed by Noah and covered with the planks of the Ark.

Then Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, who travelled extensively in the Middle East in the twelfth century, recorded this intriguing account:

Thence [from a place on the Khabur river] it is two days to Geziret Ibn Omar, which is surrounded by the river Hiddekel (Tigris), at the foot of the mountains of Ararat. It is a distance of four miles to the place where Noah’s Ark rested, but Omar ben al Khataab took the ark from the two mountains and made it into a mosque for the Mohammedans. Near the Ark is the Synagogue of Ezra to this day.

Adler 1907: 33

Jezirat Ibn Omar is the village at the foot of Cudi Dagh where Rabbi Benjamin undoubtedly saw the mosque for himself. What is especially interesting about this is that the rabbi, who knew as well as anyone the details of the antecedent Jewish tradition and the real meaning of the mountains of Ararat in Genesis 8, is evidently happy to accept the recycled Ark as the genuine item. In describing Cudi Dagh as being ‘at the foot of the mountains of Ararat’ it seems that he is attempting to reconcile the biblical location with this one, confirming this in remarking that the ancient synagogue is still there, ‘near the Ark’, and perhaps by referring to the twin mountains. When his account was written, therefore, it was clearly not only Moslems who believed that this was the resting place. A similar view is propounded by Eutychius, Patriarch of Alexandria in the ninth to tenth century: ‘The Ark rested on the mountains of Ararat, that is Jabal Judi near Mosul’ – unless this means that the name Ararat was at times applied to Cudi Dagh.

The same mountain played the same role in local Christian tradition. Much earlier, there was an early Nestorian monastery on top of Cudi Dagh, as the remarkable Gertrude Bell described in 1911, although where she got the ‘Babylonian’ evidence to which she refers so offhandedly defeats me entirely:

The Babylonians, and after them the Nestorians and the Moslems, held that the Ark of Noah, when the waters subsided, grounded not upon the mountain of Ararat but upon Jûdï Dãgh. To that school of thought I also belong, for I have made the pilgrimage and seen what I have seen … And so we came to Noah’s Ark, which had run aground in a bed of scarlet tulips. There was once a famous Nestorian monastery, the Cloister of the Ark, upon the summit of Mount Jûdï, but it was destroyed by lightning in the year of Christ 766. Upon its ruins, said Kas Mattai, the Moslems had erected a shrine, and this too has fallen; but Christian, Moslem and Jew still visit the mount upon a certain day in the summer and offer their oblations to the prophet Noah. That which they actually see is a number of roofless chambers upon the extreme summit of the hill. They are roughly built of unsquared stones, piled together without mortar, and from wall to wall are laid tree-trunks and boughs, so disposed that they may support a roofing of cloths, which is thrown over them at the time of the annual festival. This is Sefinet Nebi Nuh, ‘the ship of the Prophet Noah’.

The top of Mt. Cudi Dagh, as photographed by Gertrude Bell in 1909.

(picture acknowledgement 12.6)

The enduring, cross-religion importance of Cudi Dagh as the Ark’s landing site encourages me to ask whether its earliest association with the Ark did not precede the arrival of Christianity, but rather goes back to a Mesopotamian tradition.

In 697 BC, four years after his much discussed unsuccessful attempt to capture Jerusalem, Sennacherib, king of Assyria (705–681 BC), was on campaign again. (It would be another hundred years before Nebuchadnezzar’s successful Judaean siege.) This fifth campaign took him northwards, over the border into the land of Urartu, to deal – as Assyrian kings so often had to do – with a conglomeration of local rulers who needed straightening out. They pitched camp, he tells us in his own account of the proceedings, at the foot of Mt Nipur. We know for certain that Nipur was the contemporary Assyrian name for Cudi Dagh because, at the successful conclusion of the campaign, Sennacherib had a whole row of panels with cuneiform inscriptions commemorating this campaign carved into the base of the mountain depicting himself and proclaiming the might of the Assyrian god Assur. They are still there.

On my fifth campaign: The population of the cities Tumurrum, Sharum, Ezama, Kibshu, Halbuda, Qua and Qana, whose dwellings are situated like the nests of eagles, foremost of birds, on the peak of Mount Nipur, a rugged mountain, and who had not bowed down to the yoke – I had my camp pitched at the foot of Mount Nipur.

Sennacherib was not only present on campaign, like King Ashurnasirpal before him, but he was personally and actively involved. He wanted to get all the way to the top of the mountain, to the point that he was prepared to vacate his sedan chair and proceed painfully on foot to get there:

Like a fierce wild bull, with my select bodyguard and my merciless combat troops, I took the lead of them. I proceeded through the gorges of the streams, the outflows of the mountains, (and) rugged slopes in (my) chair. When it was too difficult for (my) chair, I leaped forward on my (own) two feet like a mountain goat. I ascended the highest peaks against them. Where my knees became tired, I sat down upon the mountain rock and drank cold water from a water skin to (quench) my thirst.

There is a fragment of sculpture in the British Museum which actually shows Sennacherib climbing a steep mountain path like this, steadied from behind by a sturdy officer. What was going through Sennacherib’s mind as he climbed Mount Nipur?

Heaving King Sennacherib up the mountain, tactfully, in a fragment of palace sculpture from Nineveh.

(picture acknowledgement 12.7)

It might have been nothing beyond the fervour of a general on campaign, but one cannot help but wonder if there was not more to it than that. If, for example, there was already some local rumour about the Ark and that particular mountain …

Sennacherib had for certain known the Flood Story since boyhood and presumably been brought up with the Assyrian idea that Mount Niṣir was the Ark Mountain. He must have mused more than once over the nature of Utnapishti’s stock of pedigree animals, for we know of his fascination with animals from other countries; as a grown man and powerful king he had a park at Nineveh in which imported natural history specimens could disport themselves freely. More than one writer has pointed out that the number of carved relief panels at Cudi Dagh – eight or nine – was surprising in view of the army’s relatively slight achievement there; conceivably the campaign had a deeper significance for Sennacherib than mere army manoeuvres. Perhaps locals at Cudi Dagh had been promoting the Ark idea for a long time – locals at iconic shrines are notoriously persuasive. If so, all the soldiers in the Nipur camp would have bought an amulet or two of the Real Ark to take home to their wives. We might imagine that Sennacherib might well think the thing worth checking out for himself while they were there.

Of course it can be replied that this is all supposition and that Sennacherib makes no more mention of Ark hunting than does his predecessor Ashurnasirpal at Mount Niṣir. If he found nothing, of course, there would be nothing in the official annals, but there are two slight items of evidence that we can bring before the jury.

A contemporary Assyrian cuneiform incantation text discloses to us a general awareness that arks were not always to be found on mountains. This spell, which, judging by the handwriting, dates to about 700 BC, is to drive out a succubus, a spectral seductress sent in the night to create a nightmare for the sufferer:

You are conjured away, Succubus, by the Broad Underworld!

By the Seven, by God Ea who engendered you!

I conjure you away by the wise and splendid God

Shamash, lord of All:

Just as a dead man forgot life,

(Just as) the Tall Mountain forgot the Ark,

(Just as) a foreigner’s oven has forgotten its foreigner,

So you, leave me alone, do not appear to me!

The magical power lies in establishing examples of separation that are irreversible: life is forgotten by the dead; the transitory embers of a traveller are cold for ever. There are many Mesopotamian exorcistic spells that rely on this principle, but this allusion to the Ark (eleppu) is unique. To my mind it implies not only familiarity with the Ark-on-the-Mountain idea, but also that there was nothing to be seen of it by then on that mountain, and that, therefore, someone had been looking for it. I submit that the use of this motif in an incantation tablet is the consequence of widespread publicity and discussion and an echo of some unsuccessful royal Assyrian hunting expedition to that end. After all, if Sennacherib had really gone up Mount Nipur looking for the Ark, all his army would have known about it, and on their return everybody in the palace, the capital, the surrounding countryside and, before long, probably the entire empire would have known about it too.

Sennacherib’s wicked siege of Jerusalem in 701 BC and the punishment that followed earned him a good deal of posthumous attention in the rabbinical commentaries of the Babylonian Talmud of the early first millennium AD. One of these passages sees Sennacherib back home, in the temple, worshipping a plank from Noah’s Ark:

He then went away and found a plank of Noah’s ark. ‘This,’ said he, ‘must be the great God who saved Noah from the flood. If I go [to battle] and am successful, I will sacrifice my two sons to thee,’ he vowed. But his sons heard this, so they killed him, as it is written, and it came to pass, as he was worshipping in the house of Nisroch, his god, that Adrammelech and Sharezer his sons smote him with the sword …

Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sanhedrin 96a

These sons, according to the underlying passage 2 Kings 19:36–37, murdered their father Sennacherib and fled to Ararat, and the murder is confirmed from contemporary Assyrian sources. That the reality of his murder should be a focus for stories against Sennacherib is natural, but it is hard to credit that the Ark-plank story could be pure fabrication many hundreds of years later with no kernel of tradition inside it. Again, one wonders if this motif does not echo an Ark-hunting event – this time more successful in that Sennacherib did come home with a bit of wood – that became part of the story tradition around the great Assyrian king. All in all, Sennacherib should have stuck to what his governess taught him.

In comparing the details of the miscellaneous Flood stories it will be remembered that Berossus, the Babylonian priest writing in Babylon in the third century BC, had useful things to tell us. He was certainly a witness to what people were saying about the Ark Mountain in his day, as we know thanks to Polyhistor and Abydenus. For example, Berossus transmitted by Polyhistor:

Also he [Xisuthros] told them they were in the country of Armenia. They heard this, sacrificed to the gods, and journeyed on foot to Babylon. A part of the boat, which came to rest in the Gordyaean mountains of Armenia, still remains, and some people scrape pitch off the boat and use it as charms.

Polyhistor’s version sounds like an attempt to harmonise two diverse traditions; Armenia to the north – the survival of the Urartu-and-beyond idea – and the Kurdish (Gordyaean) mountains further south, perhaps by then already centred on Mount Cudi.

Berossus as transmitted by Abydenus reads:

However, the boat in Armenia supplied the local inhabitants with wooden amulets as charms.

Considering how little we are otherwise told about the Ark, it is extraordinary how much emphasis is put on the commercial factor. There had obviously been a vigorous local trade in Ark mementoes with amuletic powers since time immemorial. In these remarks, in fact, we encounter an early example of the enduring human hunger for relics, culminating in pieces of the true cross and the finger bones of the holy. One thinks inevitably of booths displaying scraps of wood or pitch lining the roads to the foothills. One of their predecessors could easily have furnished Sennacherib with a heavy-duty plank fit for a king. If this does not illustrate the unchanging nature of human behaviour I know not what does.

At this point on our journey we can conclude:

1. The Ark’s resting place in Antiquity was a massive religious and cultural icon whose significance would be valued and appreciated universally; that is, across borders and across religions. We are operating in timeless terrain with modern analogies.

2. Such sites, then as now, were possessed of religious or magical power sometimes mixed with commercial implications.

3. They will always have attracted pilgrims, tourists and the sick.

4. There will always have been the inbuilt likelihood of contrast or conflict between the ‘real’ site and any number of rivals or alternatives.

5. The appearance of such rivals may or may not have provoked response from the ‘first’.

Traditions about where Noah’s Ark landed do not need to be reconciled, therefore; merely understood for what they represent.

The written and illustrated tradition of the Babylonian Map of the World is the oldest information we have; it encapsulates Old Babylonian ideas of the early second millennium BC which are a thousand years older than the tablet on which it is preserved. According to this the Ark came to rest on a very remote, gigantic mountain, located far beyond Urartu on the other side of the world-encircling Ocean, far indeed beyond the ken of man. To find the Ark, in other words, would have meant travelling to and through Urartu and virtually into infinity beyond. This was the traditional view that prevailed from at least 1800 BC, and almost certainly we would find it made explicit had we access to the whole contemporary Flood Story narrative of which the Ark Tablet is only part.

Under these circumstances it is far from difficult to understand how Agri Dagh in northeast Turkey became identified as the mountain; it was located in the ‘right’ place and direction in northern Urartu, it had outstanding geological magnificence and plausibility for the role, and, unlike the ethereal mountain of the original conception, it was near and visible and visit-able. This process, if not originally due to the Bible, was certainly confirmed and reinforced by the biblical account, the potency and effect of which was far greater than any tradition that ran before. In response, the mountain actually came to be called Mount Ararat.

This tradition of the original ‘somewhere beyond Urartu’ drawing in closer to ‘somewhere in Urartu’ resulted in, as we may say, the version which has run uninterruptedly ever since; it was old and entrenched by the time of most of the writers who ever wrote about it, and to a large extent it still holds sway today.

By the first half of the first millennium BC the Assyrians, for reasons that are unclear, had instituted a deliberate Ark-mountain change and promoted Mount Niṣir. Perhaps the reasons were several.

In 697 BC, if slight clues have been correctly put together, Sennacherib, for whom Mount Niṣir was certainly the ‘real’ Ark Mountain, encounters a second, rival set-up flourishing already at Cudi Dagh. This would be the first evidence for what later became a very strong rival to Mount Ararat and easily outlived the Assyrian Mount Niṣir, which disappeared entirely from the field with the fall of Nineveh in 612 BC and was otherwise unheard of until George Smith read the Assyrian library copies in the 1870s, when the name experienced a new lease of life.

Cudi Dagh was successively embraced by Nestorian Christianity and, then, Islamic tradition as the landing place for Noah or Nuh’s boat. In the course of time, other, less durable, Ark mountains made their appearance.

Ironically, whatever phenomena adventurers may claim to have found, it is Mount Ararat today that is closest in location and spirit to the original conception of the Babylonian poets.

The Babylonian Map of the World, by the way, is full of other secrets and to wander after them now would take us far beyond this book into cuneiform byways of astrology, astronomy, mythology, and cosmology (at least), brave journeys themselves that cannot be undertaken here. The map story is far from concluded. The map’s uniqueness from our point of view, however, does not mean for a minute that it was such a rarity in its own day. On the contrary, it is probable that many such maps existed, both on clay and on bronze, fulfilling different functions and even expressing different theories. One reason for this conclusion is that the Babylonian tradition exemplified by the Map of the World found its counterpart in the maps known to historical geographers as ‘T-O’ or ‘O-T’ maps, which survived from the Early Middle Ages until perhaps the fifteenth century AD. The origin of this name lies in the fact that these European maps show the world as a disc surrounded by the mare oceanum, with a T fixed in the middle that represents the three major waterworks that divide the three parts of the earth. These maps bear an uncanny – and usually unexplained – resemblance to the Babylonian Map of the World, with its N→S River Euphrates transversed by the waterway to the south. The resemblance is such that the European maps seem literally to be a reinterpretation of a Babylonian model.

A so-called T and O map by Isidore of Seville dating to 1472. Its antecedents are unmistakable.

(picture acknowledgement 12.8)

Computerised reconstruction of the Babylonian Map of the World; front view.

(picture acknowledgement 12.9)

That the Babylonian design survived and could exert its influence so long after the event is surely a further demonstration of what followed when Greek mathematicians and astronomers came to investigate Babylonian cuneiform records. Surely they copied whatever they found interesting onto papyrus for consideration and development once they got home, and that would have included any maps and diagrams that they came across in the libraries.

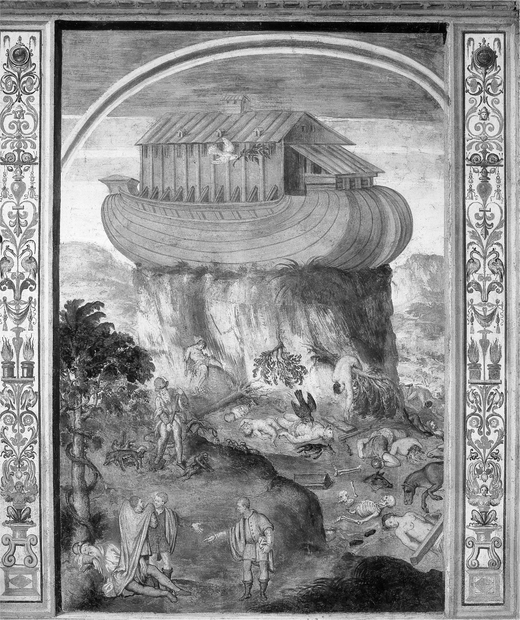

Noah’s Ark lands convincingly on the Mountain, as painted by Aurelio Luini (1545–1593).