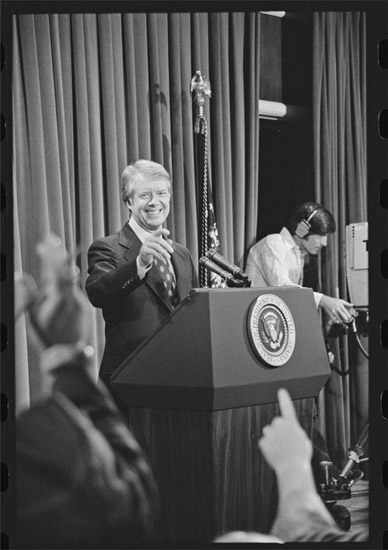

Figure 10.1 Pesident Jimmy Carter

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540 USA, US News and World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, LC-DIG-ppmsca-09783.

The Iranian revolution of 1979 was an Islamic revolution and, as such, it rejected the models of modernisation offered by Washington, Moscow and Beijing. In fact, it turned away from the whole concept of modernisation. Its aim was to return Iran to the world which had been destroyed by Western imperialism in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and to recreate a theocratic state ruled by Sharia or Islamic law. Why had Iran, viewed as the main ally of the US, suddenly turned into its greatest enemy – the Great Satan?

Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, ruler of Iran from 1941, adopted the title of Shahanshah (King of Kings) in 1967 and, as such, exercised supreme power. He initiated a White Revolution, in 1963, the aim of which was to modernise the country – in the Western sense of the word – rapidly. The Shah’s revolution collided with the ordinary Iranian’s belief that the clergy, the ayatollahs, should frame policy. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini told the Shah he was a wretched, miserable man. A secular state for Muslims was sacrilege and could lead to jihad – a holy war.

It was clear that by 1976, the Shah’s White Revolution was running into serious trouble. The government collapsed in December 1978 when around a million marched in Tehran calling for the removal of the Shah and the return of Ayatollah Khomeini. The Shah left Iran the following month. On 1 February 1979, the Ayatollah landed at Tehran airport and was welcomed by an adoring crowd as they regarded him as the imam who would redeem his people. Khomeini rejected Western society but not the technology and science it had produced because these were to be used to develop the new Islamic state.

President Jimmy Carter, a Baptist, thought that a line of communication could be established with the Ayatollah. Iranian students stormed the US embassy in Tehran, on 4 November 1979, and held fifty-two US diplomats and citizens

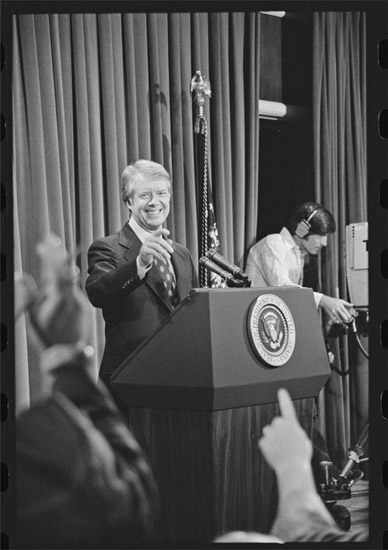

Figure 10.1 Pesident Jimmy Carter

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540 USA, US News and World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, LC-DIG-ppmsca-09783.

hostage for 444 days. The president tried to resolve the crisis peacefully but made the fundamental mistake of trying to negotiate with the Iranian government rather than with the person who actually held power, the Ayatollah, and was contemptuously rebuffed. A botched American attempt to rescue the diplomats amounted to the greatest humiliation the US ever suffered in the Middle East. A small victory emerged from the wreckage of US-Iranian affairs. Six US diplomats had managed to escape and found refuge with the Canadian ambassador. They knew it was only a matter of time before they were discovered and tried as spies and executed. Tony Mendez, a CIA officer, came up with a daring plan to get the diplomats out of Iran. He set up a film production company, Studio 6, in Hollywood and promoted it so well that Steven Spielberg sent a script to it! The diplomats were to become production staff involved in the making of a film in Iran. They learnt their roles and managed to fly out of Tehran with the rest of the film crew in a Swissair jet. They were welcomed as heroes by President Jimmy Carter, but Tony Mendez stayed in the background, and his key role was only made public in 1997. The 2012 film, Argo, tells this gripping story with a touch of Hollywood exaggeration.

Moscow was not sure how to react to the events in Tehran. On the one hand, the Tudeh or communist party had a great opportunity to expand its influence and told Moscow it was backing Khomeini. The Soviets were aware that Iran was promoting political Islam in Afghanistan and further afield. In 1983, the Tudeh party was smashed and hundreds were executed, but others reconverted to Islam in order to be released from prison. From a Marxist perspective, Islamism was a throwback, a rejection of the modern world. For a Marxist it was unbelievable that religion could form the basis of a viable political philosophy. Because it was reactionary, it would naturally gravitate to the imperialist camp, led by the US.

Afghanistan is a huge, underdeveloped country of thirty million people. The dominant ethnic group are the Pashtuns, and they dominate Kabul, the capital, the centre and the south. Tajiks, Uzbeks and Turkmen are the majority in the north so the country has never really been unified. It is dominated by tribes and clans that are fiercely independent. Britain detached part of eastern Afghanistan and added it to present-day Pakistan, and those inhabiting the North West Frontier, the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and Waziristan, have traditionally been ignored by the Pakistani government in Islamabad. The feeling of being cut off and different is the natural response. Hence ethnically much of eastern Afghanistan and western Pakistan is similar.

How was the country to modernise? There were two main models: the Western and the communist. The first step was to make the country a republic, and the king was deposed in July 1973 by his prime minister and cousin, General Mohammad Daoud, but no outside power was involved. Daoud identified communists and Islamists as the greatest threat to stability and came down on them hard.

The People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan was founded in 1965 and consisted of two Marxist factions which mirrored the divisions in the country. Nur Mohammad Taraki and Hafizullah Amin, headed the Khalq (or the masses), the more radical, mainly rural Pushtun speaking wing. The Parcham (or flag) were the other, predominantly urban Farsi speaking, group, led by Babrak Karmal. The main ideological difference between the two was the Parcham took the view that the country had to be industrialised before it could move towards communism. Khalq, on the other hand, wanted to seize power and then industrialise and modernise. Khalq was dominated by Pushtuns from non-elite clans. Parcham supported Daoud’s attempts at agrarian reform, and Moscow favoured them.

Moscow was taken by surprise when, on 27 April 1978, Daoud and other ministers were assassinated by the Khalq. Nur Muhammad Taraki became president and Hafizullah Amin prime minister, and it became clear very quickly that the Khalq were in a hurry so most of the Parcham group was imprisoned or killed. Babrak Karmal was sent to Prague as ambassador. Khalq was dependent on the Soviet Union for aid and arms and Taraki, especially, was frustrated by the fact that Moscow would not provide the amount of arms and helicopters he wanted.

Amin, wisely, had sworn loyalty to the Soviet Union, but it soon became quite clear that he did not listen to a word the Soviets said. He engaged in a series of radical reforms which alienated more and more people. Particularly unpopular were agrarian reforms and moves to curtail the influence of the mullahs.

On 17 March 1979, Leonid Brezhnev placed Afghanistan on the Politburo agenda. The situation in Herat, near the border with Iran, was causing concern. Andrei Gromyko informed the meeting that the Afghan army division sent to restore order there had disintegrated and other army units had defected to the insurgents’ side. Gromyko, the minister of defence, Dmitry Ustinov, and Yuri Andropov, the KGB chief, all argued that Soviet troops be sent to crush the insurgency, but Aleksei Kosygin, the prime minister, argued strongly against intervention and won the day.

Hafizullah Amin was invited, in September 1979, to Taraki’s residence to discuss policy. Taraki’s guards opened fire and killed two of Amin’s assistants, but Amin escaped. Now it was a straight contest: who would kill the other first? Amin was more cunning, and Taraki was arrested, tied to a bed and suffocated with a pillow.

Andropov forwarded a letter to Brezhnev on 1 December 1979 which accused Amin of secret contacts with an American agent, attacks on Soviet policy and a move towards neutrality. It is now known that the US had broken Soviet codes and was able to infiltrate Soviet communications. The Americans spread disin-formation about Amin having contacts with them, and Moscow took the bait.

On 10 December, Marshal Ustinov, minister of defence, summoned Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov, chief of the general staff, and informed him that the Politburo had decided to intervene militarily. About 80,000 soldiers or eight divisions would subdue the country, but Ogarkov disagreed and stated that thirty to thirty-five divisions would be needed. Ustinov cut him off and told him: ‘We make policy here. Your task is to carry out the military tasks assigned to you.’ On 12 December, Leonid Brezhnev, in no fit state to resist, signed an order to prepare the invasion.

A battalion of Special Forces (Spetsnaz), consisting of Central Asians, had been formed in May 1979, and the 500 men were flown to Bagram, in Afghan uniforms, and moved to Kabul on 21 December. Two KGB units joined them. At 3 p.m. on 25 December, almost 8,000 Soviet troops crossed the border into Afghanistan, most of them by air. The primary target for the KGB units was the Tadj-Bek Palace in Kabul where Amin was hiding; he naively thought the Soviets were coming to protect him. He and his personal guard, up to 150 men, were all to be killed and relatives and aides were also to die. At a dinner on 26 December, Amin was very careful what he ate and drank but trusted his own cooks who were Soviet Uzbeks but soon everyone was writhing in pain. Amin was given an injection and a drip feed by a Soviet doctor who was not privy to the fact that Amin was to be assassinated. The Soviet troops then attacked, and Amin rushed from his sick bed to see what was happening, but he was mown down along with his five-year-old son who was clutching his leg. The KGB lost about a hundred men killed or wounded. Babrak Karmal, a long-standing KGB agent, was installed as the new leader.

According to one of the Soviet commanders, the operation was poorly planned, causing chaos with some units unaware of the existence of other units. A paratroop division fired on the commander’s company, killing some of his men.

On 27 December 1979, Karmal announced that he was president, prime minister and also general secretary of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan. The Soviets, to justify their assassination of Amin, revealed that since September he had liquidated over 600 communists. The government was filled with exiles who had returned with him.

The Soviets thought that they would be in and out of Afghanistan quickly. The objective was to stabilise the situation and withdraw after about six months, leaving behind only political advisers and intelligence agents. Lieutenant General Ruslan Aushev, an Afghan war hero who spent five years there, commented in 2009:

We were there for 10 years and we lost more than 14,000 soldiers, but what was the result? Nothing. We wanted to bring peace and stability to Afghanistan, but in fact everything got worse.

(BBC News, 14 February 2009)

A vicious civil war ensued with the mujahidin (strugglers for freedom) receiving arms and funding from the US and even China. When the Soviets invaded, Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor, punched the air and exclaimed: ‘They have taken the bait!’ In a note to the president, he crowed: ‘We now have the opportunity to give the USSR its Vietnam War’ (Haslam 2011: 326). In February 1980, Andropov travelled to Kabul and met Karmal and submitted an optimistic report to the Politburo as the new leader understood what he had to do to stabilise the situation. Ustinov was less optimistic and thought it would take up to a year and a half to stabilise Afghanistan.

The Soviet Union was blithely unaware of the hole it was digging itself into. On 23 June 1980, at a Party Central Committee plenum, Andrei Gromyko, the foreign minister, spoke eloquently about the rising power of the Soviet Union (Wilson Center Digital Archive [Russian text]):

The most important factor in international affairs [is] the constant strengthening of the position of socialism on the international stage. The world map bears eloquent testimony to this. In the eastern hemisphere there is glorious Cuba; in South East Asia, Vietnam is building a new life; the large family of fraternal parties has welcomed Laos and the Republic of Kampuchea; a form of socialist development is evident in different countries on various continents: Angola, Ethiopia, South Yemen, and a short time ago, Afghanistan.

By 1982, Gromyko had regretted his support for the invasion, and Anatoly Kovalev, when asked by him to take over the Near and Middle East desks at the ministry, flatly refused as he wanted nothing to do with the war. Evgeny Prima-kov told Soviet diplomats that it was futile to bring ‘revolutionary change’ to Afghanistan, and Gromyko muttered his support. Andropov, now Soviet leader, in March 1983, conceded that there had never been the prospect of a swift victory over the mujahidin.

The turning point in the war came in the summer of 1986, when the US began to supply Stinger lightweight ground-to-air missiles to bring down Soviet helicopters which hitherto had given the Soviets control of the air. The US military and CIA opposed the move but George Shultz, the secretary of state, sided with the radicals. US aid to the mujahidin was channelled through the Pakistani Directorate for Inter-services Intelligence (ISI), and billions of dollars and equipment flowed through their hands and they used it to arm the fundamentalist groups. By 1986, they believed the Soviets would be defeated, and the battle for the future of Afghanistan got under way. The Islamists made clear that they opposed both Great Satans: the Soviet Union and the US (Westad 2005: 353–7).

At the height of the conflict there were over 120,000 Soviet troops in the country (wholly inadequate for a country the size of Western Europe). The Soviet Army was not defeated as it held the cities but lost control of the countryside and found it could occupy territory but when it retreated, the mujahidin simply returned to take control. It lost about 14,000 dead and thousands more wounded during the conflict. Gorbachev conceded defeat and withdrew from Afghanistan on 15 February 1989. The Saudis were pleased and immediately handed the Soviet leader a $4 billion loan. Secretly, 200 military and KGB advisers remained in Kabul and when President Yeltsin discovered this subterfuge, he withdrew them.

The Afghan invasion was one of the worst mistakes ever made by a Soviet leader. Not only did it unite Islam against Moscow, it also led to the US supporting the ‘God fearing mujahidin’ against the ‘godless communists’. President Jimmy Carter, in so doing, also committed one of the worst mistakes of an American leader. How did this come about? The CIA, in 1981, could choose which Afghan opposition group to support: either the moderate Islamic, nationalist, pro-monarchical Afghan parties or a group of three fundamentalist Islamic factions. The latter promised, after expelling the Soviets from Afghanistan, to then move into Tajikistan and begin undermining communist rule there and in the rest of Central Asia. Unfortunately, the Americans went for the short-term gain and ignored the long-term consequences of supporting Islamic fundamentalists and were to pay a heavy price for their short-sightedness.