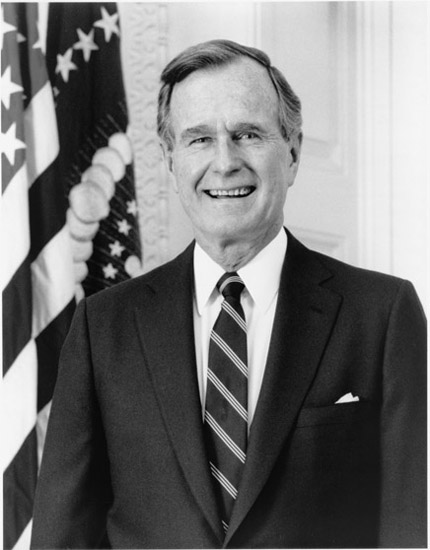

Figure 13.1 Margaret Thatcher

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540 USA, US News and World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, LC-DIG-ppmsca-09786.

Margaret Thatcher was keen to learn more about the Soviet leadership, so she invited several top politicians to London in December 1984, but only Mikhail Gorbachev would come. The British prime minister was very impressed by Gorbachev’s willingness to engage in debate. She commented (BBC, 16 December 1984):

I like Mr Gorbachev. We can do business together. We both believe in our own political systems. I firmly believe in mine. He firmly believes in his. We are never going to change one another. So that is not in doubt, but we have two great interests in common: that we should do everything we can to see that war never starts again, and therefore we go into the disarmament talks determined to make them succeed.

Mrs Thatcher immediately made for Camp David to brief her friend President Reagan on her new acquaintance. She persuaded Reagan that the West could do business with Gorbachev.

Konstantin Chernenko died on 10 March 1985. Gromyko had struck a deal with Gorbachev which was that he would vote for him, and Gromyko was aware, as someone whose career was in government, that he would never head the party. A quick vote was called for because the Americans might use the impasse to their advantage, but two members did not make it to Moscow on time: the Ukrainian and Kazakh First Secretaries. Had they been present, it is possible that Viktor Grishin, the Moscow Party boss, might have been elected leader. Egor Ligachev became the new leader’s no. 2; Nikolai Ryzhkov, an engineer, became prime minister in September 1985; Viktor Chebrikov stayed as KGB chief.

Gromyko expected Georgy Kornienko, an Americanist, to succeed him. This would allow President Gromyko – he became Soviet president in June 1985 – to exert a huge influence on foreign affairs. Gorbachev, on the other hand, did not want a Gromyko clone as foreign minister and instead chose Eduard Shevardnadze, the Georgian First Secretary, who was a charming comrade but with imperfect Russian and even less knowledge of foreign affairs. Anatoly Dobrynin, the suave Soviet ambassador in Washington, was not pleased and commented to George Shultz that an ‘agricultural type’ (i.e. a stupid peasant) had taken over. It was plain that Gorbachev planned to run the show himself. The link between foreign and domestic policy was crucial as better relations with the West would allow less spending on defence. Shevardnadze shared Gorbachev’s concern for change and on Afghanistan they saw eye to eye: it had been a disaster from the very start. The most influential adviser was Aleksandr Yakovlev. Squat – the British ambassador Rodric Braithwaite labelled him a ‘dyspeptic frog’ – a war veteran, he had been an exchange student at Columbia University and had met Gorbachev when, as Soviet ambassador in Ottawa, he had accompanied him round Canada. Yakovlev was no friend of the US but regarded Stalin as a Russian fascist. On the other hand, during his years in Canada, he never developed an understanding of how a market economy worked.

Figure 13.1 Margaret Thatcher

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540 USA, US News and World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, LC-DIG-ppmsca-09786.

When Vice President George H. W. Bush attended Chernenko’s funeral, he handed Gorbachev a letter from the president proposing a meeting in the US. Two weeks later, Gorbachev agreed in principle but suggested they meet in Moscow. In June, they agreed their first meeting would take place in Geneva, in November 1985. During the spring and summer Gorbachev and Reagan exchanged letters quite frequently, and this permitted both sides to float proposals to discover if there was any common ground. In October, Gorbachev introduced the concept of ‘reasonable sufficiency’ in assessing the size of the armed forces.

When Donald Regan became chief of staff, in February 1985, he was shocked to discover that Nancy Reagan regularly consulted an astrologer, Joan Quigley, and that, following the failed assassination attempt, her husband had become a devotee. In modern times, the Reagans were almost certainly the only Western leaders to seek guidance which was neither Christian nor scientific. Regan later wrote:

Virtually every major move and decision the Reagans made during my time as White House chief of staff [February 1985–February 1987] was cleared in advance with a woman in San Francisco who drew up horoscopes to make certain that the planets were in favourable alignment for the enterprise.

Some church leaders demanded that the Reagans abandon their ‘ungodly’ reliance on Quigley. The Reagans issued a statement that, unlike Caesar’s wife, they believed in predestination. No decisions or policies had been based on horo-scopes as astrology was merely a hobby (The Times, 3 November 2014).

The Geneva summit, on 19 and 20 November 1985, was a watershed in relations. Gorbachev’s attitude to Reagan was that he was more than a conservative: he was a political dinosaur. The US president reciprocated by viewing the Soviet Union as Upper Volta with rockets but potentially a threat to the free world, and he despised communism. His dislike of the Soviet Union and its people was abstract because he had never visited the country, but the few Russians he had encountered – Dobrynin and Gromyko – he liked.

Gorbachev sided with the military in thinking SDI could be countered. He told Shultz beforehand that he believed the aim of the US was to force the Soviet Union into a corner and, anyway, SDI would bankrupt the US. The Soviet Union would engage in a build-up which would pierce the US’s shield, but this was bluff. A party document, in late summer 1989, concluded that the USSR was ‘increasingly out of touch with the latest technologies’.

Gorbachev proposed that the superpowers issue a statement that neither would be the first to launch a nuclear war. Reagan rejected this as it precluded a nuclear response to a conventional Soviet invasion of Western Europe. The compromise reached was to agree to prevent any war between them, whether nuclear or conventional. They also pledged not to seek military superiority. Gorbachev wanted American help to secure a settlement in Afghanistan. Reagan was irritated by Gorbachev’s harping on SDI as offensive and countered by claiming that the early warning system at Krasnoyarsk contravened the ABM treaty. (It did.) Reagan read out a statement proposing a 50 per cent cut in offensive nuclear arms and other weapons reductions. Gorbachev agreed but said he was disappointed they had not made more progress but, overall, they hit it off and one of the reasons for this was a fireside chat.

In May 1986, the new political thinking in foreign policy was formally launched. The main components were:

Gennady Gerasimov, renowned for his suave performance and one liners, such as the Sinatra doctrine ‘we’ll do it our way,’ became the foreign ministry press spokesman.

In the months following the summit, the Soviets launched proposal after proposal to end the arms race. Everything now appeared to be negotiable, and Moscow’s flexibility caught Washington off guard. In January 1986, Gorbachev dramatically proposed the phasing out of nuclear weapons by 2000 and on intermediate range missiles, the Soviet position was almost the same as the American. Moscow was willing to accept limits on ICBMs, and the balance of conventional forces in Europe and Soviet troops, perceived as a threat by NATO, would be redeployed but the Soviet military bridled at cuts in conventional forces. In February 1986, Gorbachev referred to Afghanistan as a ‘bleeding wound’ and signalled that the USSR wanted out in order to improve relations with Washington. Gorbachev, when it came to arms reductions, always encountered opposition from Marshal Sergei Akhromeev, the chief of staff, who confessed he did not believe in the elimination of all nuclear weapons by 2000. The military wanted to keep their SS-20s in place but Gorbachev received strong support from Eduard Shevardnadze and Anatoly Adamishin, deputy minister of foreign affairs. Gorbachev was still not in a position to overrule the military whom he conceded had primacy in security matters.

On 15 April 1986, the Americans bombed Tripoli, after a bomb attack which had killed three people and injured 229 in a West Berlin discothèque on 5 April. Two of the dead and seventy-nine of the injured were US servicemen. It was a clear warning to the Libyan leader, Muammar Gaddafi, to cease such acts or face severe reprisals. The CIA began to supply the mujahidin with Stinger missiles which were promptly used to bring down Soviet helicopters. In May, Reagan declared that the US would no longer observe the unratified SALT II agreement.

The shock of the Chernobyl explosion in April 1986 led the Soviet leadership, on 29 May, to drop their demand that SDI should be scrapped. Laboratory testing was now acceptable but external deployment and testing would not be countenanced. This was an opportunity for Washington to make progress in arms negotiations, as they all concluded that SDI had rattled Moscow, and Washington was aware that Gorbachev had provided funding to build a comparable system.

The first direct conflict between the two leaders occurred in August 1986, when the Americans arrested Gennady Zakharov, a Soviet UN employee, when he was on the point of purchasing classified documents, and the KGB responded by arresting Nicholas Daniloff, the Moscow correspondent of US News and World Report. Reagan wrote a personal letter to Gorbachev confirming that Daniloff was not a spy. However, Shultz and the editor of US News and World Report were aware that Daniloff had acquired secret Soviet documents and photographs and had passed them on to the State Department. Shultz was furious when he discovered that the CIA had used Daniloff as a contact with a Soviet source and had discussed him on an open telephone line. He regarded the whole episode as a CIA ploy to stymie his efforts to improve relations with the Soviet Union.

During the three weeks Gorbachev took to respond to a Reagan letter, the US ordered twenty-five Soviet UN employees, whom they deemed to be engaged in intelligence gathering, out of the country. Moscow was warned that if it retaliated, more would go. The Americans also demanded that Yury Orlov, a prominent human rights campaigner, be released and permitted to move to the US, along with his wife (they eventually left). Shultz’s excellent personal relations with Shevardnadze, which included taking the foreign minister on a boating trip down the Potomac, serenading Shevardnadze with the song ‘Georgia on My Mind’. He arranged for three diplomats from the US embassy to sing it in Russian. The comment was: ‘Thank you, George. That shows respect.’ Daniloff was released. Zakharov was expelled, and Reagan then announced the Reykjavik summit, in October 1986, but this was not the end of the affair. After the summit, Moscow ordered out five US diplomats and Washington retaliated by sending fifty-five Soviet diplomats packing.

In the run up to the Reykjavik summit, Gorbachev offered more and more concessions. ICBMs could be eliminated over ten years and US and Soviet tactical nuclear weapons could be removed from Europe. The sticking point, as before, was SDI. Initially, Gorbachev gained the upper hand. Noting that Reagan’s answers were vague, the Soviet leader then posed specific questions. The president then shuffled his cards to find the right answer but some of them fell on the floor. When he had gathered them up, they were out of order. Reagan accepted Gorbachev’s goal of the elimination of nuclear weapons but refused to agree that testing SDI should be restricted to the laboratory. The president could have agreed to laboratory testing without slowing down research, but he was unaware of this. He offered to share SDI technology once the system was in place. SDI, from Reagan’s point of view, was to make nuclear war impossible, but Gorbachev did not accept this and wanted to eliminate all nuclear weapons, which would make SDI irrelevant.

Marshal Akhromeev, at Reykjavik, was unhappy with Gorbachev’s proposed concessions but afterwards proposed to the General Staff Academy that both superpowers move to defensive strategic planning. This implied that the Soviet doctrine of automatic massive retaliation after an American attack would be revised. The new policy would be to engage in defensive operations which might last several weeks and, if that failed, a massive counter-attack would be launched (Service 2015: 227). This was subjected to severe criticism by officers, but it did reveal that Akhromeev was thinking creatively about how to avoid nuclear Armageddon.

Margaret Thatcher’s reaction to President Reagan’s proposal to abandon nuclear deterrence was as ‘if there had been an earthquake beneath my feet’. Another who was in despair was Kenneth Adelman, director of the US arms control and disarmament agency, who failed to dissuade the president. ‘He’d hear the arguments, respond to bits, and then reiterate his goal of a nuclear free world.’ Adelman, in his memoirs, recounted that he once attended a New York soirée at which a celebrated anti-nuclear writer, Jonathan Schell, outlined a utopian proposal for nuclear disarmament. ‘I was dumbfounded’, recalled Adelman, ‘and said that I had heard such notions from only one other person in my life, the President of the United States’ (The Times, 11 November 2014).

The two leaders came tantalisingly close to an official statement, but unofficially they had agreed on more issues than ever before. The Soviets now accepted on-site inspection and human rights as subjects for negotiation. When he returned to Moscow, Gorbachev gave vent to his frustration at a Politburo meeting, using insulting, demeaning language to describe Reagan but, when he had calmed down, he confessed that the two leaders were ‘doomed to cooperate’. Formal failure at Reykjavik resulted in a better INF agreement in 1987, when all missiles were eliminated. Britain and France would have resisted giving up their nuclear deterrent if Reagan’s acceptance of the elimination of all nuclear weapons had remained.

A stroke of luck for Gorbachev was the flight on 28 May 1987 of Mathias Rust, a young West German adventurer. From Finland he flew his small Cessna plane to Moscow, circled the Kremlin and landed in Red Square. Gorbachev was attending a Warsaw Pact meeting in East Berlin and felt humiliated when he heard the news. Hitherto, he had hesitated to do battle with the General Staff and the Ministry of Defence which had resisted arms concessions, but now he had the chance to establish his authority. The minister of defence was sacked and replaced by a general who had spent much of his career on personnel matters. About 150 generals and officers were put on trial or demoted. Gorbachev and Shevardnadze now concluded that no disarmament treaty could be agreed unless the Soviet Union conceded that it had more medium range nuclear missiles in Europe than NATO, and this meant that the Kremlin was now willing to negotiate a separate treaty on intermediate- and short-range nuclear forces. Gorbachev had abandoned his insistence on an agreement on SDI before progress on other weapons systems.

Reagan pursued four objectives in his relations with Gorbachev:

Gradually the Soviet side came to realise that progress on these issues could be of mutual benefit. If progress were made on one issue, it would not be that the Soviets had lost out to the Americans as zero-sum diplomacy came to an end. The breakthrough came in November 1987, when Shultz and Shevardnadze reached agreement on verification.

In December 1987, Gorbachev travelled to Washington, and he and Reagan signed the epoch-making INF agreement. It eliminated a whole class of nuclear weapons, those carried by intermediate range ballistic missiles – over 2,500 in all. It was the first arms agreement signed by the superpowers since 1979. The verification procedures were so intrusive that American officials began to worry that the Soviets might learn too much about US defence. On the last day of his visit, on 10 December, en route to the White House, Gorbachev suddenly instructed his driver to stop, and he got out and started working the crowd. He was enthusiastically received and was exhilarated by the warmth and emotion he encountered. Gorbymania was born. Over lunch, he confided that his reception had made a deep impression on him. Then everyone went out to the South Lawn of the White House to address the public. A shower of rain interrupted them, and President Reagan put up his umbrella for Nancy to shelter under. This struck the Russians as odd as back home it was the task of the wife to look after her husband, not the other way round. The Soviet delegation stayed at the Madison Hotel where the minibar was replete with wines and spirits. They imbibed so heartily that the head of mission had to ask the hotel to replace the alcohol with soft drinks! Outside, they gorged on Big Macs and Cola.

Gorbachev’s wife Raisa was not so impressed by America and on a trip around Washington declined to get out of the car to view the Lincoln Memorial. Her comments were normally negative, and she had the habit, after shaking hands with a row of guests, of opening her handbag and taking out a wet wipe to clean her hands. This became known as the Pontius Pilate syndrome! The relationship between Raisa and Nancy Reagan was frosty as they were always trying to upstage one another.

Shevardnadze and Shultz established quite a close relationship and the latter was well aware that the Georgian did not like jokes about national stereotypes, but this was in sharp contrast to Reagan, who was always telling Irish jokes to break the ice with Gorbachev. Someone should have explained to him that the Irish love to tell jokes which ridicule the national character.

Paddy goes to the doctor in Dublin and complains about bad feet. He is advised to walk a mile a day. Some time later he phones and says: Doc, I’m in Cork, what do I do now? Paddy goes to see the doctor and says his feet are killing him. The doctor advises him to put on a clean pair of socks every day. Later he phones and says: ‘Doc. I took your advice but I can’t get my shoes on now!

Reagan asked US embassy staff in Moscow to collect Russian jokes but Bush put an end to such practice.

Shultz negotiated hard with Gorbachev but usually with tact. However, in April 1988, he informed the Soviet leader the only thing that was stopping America treating the USSR as another Panama was that it had nuclear weapons. The previous December, Gorbachev had told Bush that the Soviet Union was building a supercomputer and giant computers for industry. Bush realised later that this was pure fiction (Service 2015: 255, 257, 275). The Soviet leader had great faith in Soviet electronics, but one of the puzzles about Soviet industry was its weakness in electronics. Brilliant in physics, chemistry and other sciences, the USSR was a laggard in electronics and imported many GDR electronic components for its machines.

Psychologically, the visit came at a vital moment for Gorbachev. At home, he was finding it harder and harder to counter the populist appeal of Boris Yeltsin and opposition to perestroika from the party and the people. As things became more complex domestically, they flourished internationally. Doubters abroad were being silenced while domestically they were becoming more strident. The Washington summit cemented a partnership with the US and the end of the Cold War was in sight. Things began to change also in the Soviet Union and a softer line on human rights was taken and Jews who wished to emigrate were freed from detention and permitted to leave. The Russian Orthodox Church, with the support of the regime, marked the millennium of Christianity in Russia and the Soviet Union and churches were refurbished and reconsecrated.

In February 1988, Gorbachev announced that Soviet forces would be withdrawn from Afghanistan and an agreement on this was signed in April. In May, Soviet troops began to leave Mongolia and it was hinted that they would soon be departing Eastern Europe. Reagan travelled to Moscow for the last summit with Gorbachev, and on 1 June they exchanged the instruments of ratification which implemented the INF treaty. Reagan strolled in Red Square with Gorbachev and when asked by journalists if he still regarded the Soviet Union as the evil empire, answered in the negative. He had changed his mind, as had many Americans, with only about 30 per cent now regarding the Soviet Union as evil and threatening.

At the UN in December 1988, Gorbachev announced that Soviet armed forces would be reduced unilaterally by half a million within two years. Soviet troops, stationed in the GDR, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, would be gradually withdrawn. Astonishingly, he did not expect the US to reciprocate. The remarkable thing about this speech at the New York summit was that neither Gorbachev nor Shevardnadze had consulted the defence ministry before announcing the cuts. In protest, Marshal Sergei Akhromeev, chief of the General Staff, announced his resignation the same day, but another source states that he resigned for health reasons. He had gone along with strategic arms reductions but drew the line at conventional cuts if the US did not reciprocate. It was clear that the Soviet leader was engaged in a high-wire act with his own military. Gorbachev asked Akhromeev to stay as his adviser.

Gorbachev used the UN forum to elucidate his view of universal human values and stressed that freedom of choice was a universal principle. Many wondered if this extended to Eastern Europe. Afterwards he met President Reagan and President-Elect George H. W. Bush on Governors Island. The Armenian earthquake disaster intervened and the Soviet leader had to cut short his visit and cancel a visit to Cuba.

In 2010, Gorbachev, reflecting on the extraordinary relationship with Reagan, commented (The Times, 24 January 2011):

I think it was stroke of luck that history brought two such like-minded people together… I am proud of what we did together because it brought us closer to abolishing nuclear weapons. And it opened the door to a new kind of co-operation in the world… We must pay tribute to Ronald Reagan. He was a great man.

The impetus in Soviet-American relations was now lost as President Bush, after assuming office in January 1989, took his time to elaborate his foreign policy priorities. Bush felt that Reagan had been too quick to deal with Moscow and had been too accommodating. This revealed that the new president was having difficulty in comprehending the sea change in Soviet foreign policy. The conservative Bush administration did not want to believe that many of its cherished beliefs about the Soviet Union were dissolving before their eyes. In May 1989, Marlon Fitzwater, the White House spokesman, dismissed Gorbachev as a ‘drugstore cowboy’. But George H. W. Bush changed his mind during his extensive tour of Eastern and Western Europe in July 1989. Everyone pressed on him the need to meet Mikhail Gorbachev as momentous events were taking place. Gorbachev was disappointed that Bush’s first stop was Warsaw, not Moscow. The relationship eventually became very close and Gorbachev remarked, on one occasion, that it was not in the interests of the Soviet Union to diminish the role of the US in the world. On some occasions, he excluded his own interpreter from meetings with Bush, relying entirely on the American interpreter. This behaviour was puzzling, but one explanation would be that Gorbachev’s foreign policy agenda could only be carried out if the US shared it and continued to be the dominant world power. As one of his Soviet communist critics pointed out, this was a strange policy for a Soviet leader to be pursuing.

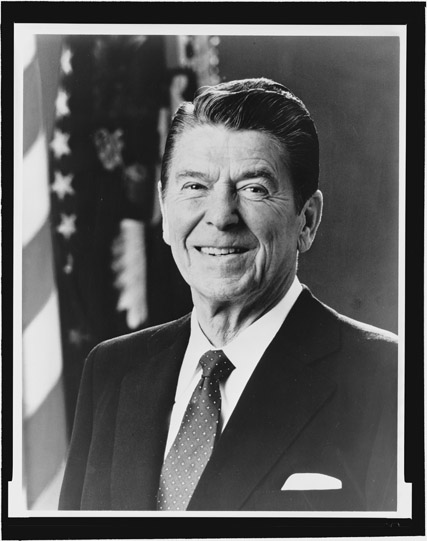

Figure 13.2 President George H. W. Bush

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, LC-USZ62-98302.

The turning point in the relationship between James Baker, who had succeeded George Shultz as secretary of state, and Eduard Shevardnadze occurred in September 1989. The latter accepted Baker’s invitation to his ranch at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Before leaving Moscow, Shevardnadze had given vent to his frustration at the tardiness of Washington’s response to Soviet arms proposals. The Soviet foreign minister stayed two weeks and developed as close a relationship with Baker as he had had with Shultz. On arrival he was presented with a ten-gallon Stetson, but enquiries at the Soviet embassy in Washington had failed to elicit information on the size of Shevardnadze’s head. So the Americans worked it out for themselves. The dashing Georgian cut quite a figure in his ten-gallon hat, cowboy boots and three-piece suit.

To underline the economic crisis back home, Shevardnadze had brought along Nikolai Shmelev, a pro-market economist, who had published some devastating analyses of the Soviet economy. The minister was desperate for a partnership with the US, whatever the cost. Without gaining anything in return, he intimated that Moscow was prepared to sign a START treaty. He confirmed that the giant Krasnoyarsk radar station contravened the ABM treaty but had hinted at this during a speech to the UN in 1986. Gorbachev was later to inform Bush that he had decommissioned Krasnoyarsk in order to ‘make things easier for the president’. The facility was not a satellite tracking station, as the Soviets had been maintaining for years, but a sophisticated battle management radar in a potentially anti-ballistic missile system. On his return to Moscow, Shevardnadze made other concessions. He accepted Washington’s demand that it be permitted 880 submarine-launched cruise missiles, but Marshal Akhromeev and others berated him for not having gained reciprocity on this issue.

A Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) document was signed on 17 January 1989, and one of the provisions was that talks would begin on reducing conventional forces in Europe. This resulted in the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty, signed in Paris by sixteen NATO states and six Warsaw Pact states on 19 November 1990.

Gorbachev faced another embarrassment when, on 25 April 1989, the British ambassador reported to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that London did not believe that the Soviet Union only possessed 50,000 tonnes of poison gas. The British government had information, from a Soviet defector, that an illegal biological weapons programme was operating. The Soviets did have a germ warfare facility at Sverdlovsk (Ekaterinburg), but Gorbachev hoped their research could be classified as defensive. The Soviet Union had been caught in breach of its obligations. On 14 May 1990, the British and US ambassadors pressed Deputy Foreign Minister Aleksandr Bessmertnykh to end the Soviet Union’s illegal production of biological weapons. Moscow conceded that the programme had been under way in breach of the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention but this was because, it contended, NATO countries had moved production to third countries. The Soviet Union agreed to end the manufacture of biological and chemical weapons, and Soviet and US stockpiles were to be destroyed by 2002 (Service 2015: 372–3, 428–9).

Shevardnadze advised Gorbachev, in November 1989, that it was very important to get Bush’s ‘public commitment for the reform programme’ and warned him that Bush was an ‘indecisive leader’ (Dobrynin 1995: 634). Bush made up his mind about perestroika before he arrived in Malta on 1 December: it was a good idea, and he had a raft of proposals about economic co-operation. The Americans had warned Gorbachev against trying to outsmart Bush at his first meeting by launching a series of new initiatives. Reykjavik obviously still rankled.

The Soviet leader understood that Bush was offering him an economic partnership, although he soon demonstrated that he had a woolly understanding of a market economy. There were informal agreements on Eastern Europe, Germany and the Baltic republics. Eastern Europe did not present a problem because Gorbachev and Shevardnadze had reiterated, on several occasions, that the Soviets would not use military force to prevent the peoples there deciding their own fate. Gorbachev said he hoped the Warsaw Pact would continue. Bush countered by saying that as long as force was not used the US would not seek to embarrass the Soviet Union in the region.

On Germany, Gorbachev counselled caution because no one in the Soviet Union favoured reunification in the short term. On the Baltic republics, he said he was willing to consider any form of association but not separation. Bush made it clear that the use of force there would be disastrous for their relationship, and the US again promised not to make life difficult there for Moscow. He also told Gorbachev that he did not accept Mrs Thatcher’s views on Germany.

She thinks history is unjust. Germany is so rich and Great Britain is struggling. They won the war but lost an empire and their economy. She does the wrong thing. She should try to bind the Germans into the European Community.

(Service 2015: 423)

On arms, it was agreed to work towards the signing of a conventional forces in Europe (CFE) treaty, in 1990. A START treaty might be ready for signing at the next proposed summit, in Washington in mid-1990, but there were also sharp disagreements. Bush was critical of Soviet arms deliveries to Latin America and the behaviour of Moscow’s ally, Cuba. Gorbachev retorted that he had kept his promise not to supply arms to Nicaragua. On Cuba, the Soviet president thought the best solution was for President Bush to meet Fidel Castro face-to-face and offered to arrange a meeting. Bush brushed this aside contemptuously and advised Gorbachev to stop wasting his money on the island. Gorbachev took umbrage at Bush’s assertion that Western values were prevailing. This implied, countered Gorbachev, that the USSR was caving in to Western norms. He preferred the term ‘universal, democratic values’. Eventually, they agreed to say ‘democratic values’. Malta was a watershed in Soviet-American relations. Gorbachev assured Bush that he, as other Soviet citizens, did not consider the US the enemy anymore. Shevardnadze put it graphically. The superpowers had ‘buried the Cold War at the bottom of the Mediterranean’ (Beschloss and Talbott 1993: 165). There was another bonus in 1990, when Shevardnadze transferred the Barents Sea shelf to the US.

Gorbachev came up with the expression ‘Europe is our common home’ (the concept was elastic: it also included the US and Canada) in Paris in February 1986, during his first visit to Western Europe after taking office. He chose France because it was a nuclear power and it would be a feather in his cap if he could interest the French in a nuclear-free world, but President Mitterrand proved quite unresponsive. When Mitterrand visited Moscow, in July 1986, he confided to Gorbachev that he opposed the whole idea of SDI and viewed it as accelerating the arms race instead of slowing it down. After the Reykjavik summit, however, the French repeated their commitment to nuclear deterrence, disappointing Gorbachev.

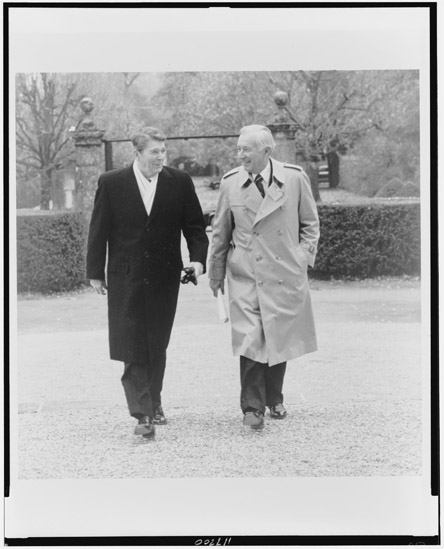

Figure 13.3

President Ronald Reagan and President Mikhail Gorbachev

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540 USA, LC-USZ62–117700.

In April 1987 in Prague, the Soviet president floated his pan-European idea but found little response from the leaders of Western Europe who preferred to take their lead from the Americans. When British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher visited Moscow in March 1987, she forcefully reiterated her commitment to nuclear deterrence (‘nuclear weapons have been invented, you cannot de-invent them,’ she said). She also believed the goal of the Soviet Union was to promote communism worldwide. Nevertheless, the two leaders got on extremely well as Mrs Thatcher enjoyed a good argument. As she had the ear of President Reagan, it was important for Gorbachev to attempt to win her over to his way of thinking. She was enthusiastic about something else: perestroika.

A joke circulated after the meeting.

The two leaders are having tea at Gorbachev’s dacha. A dog appears. ‘Come, come, Geoffrey Howe, come and say hello to the nice lady,’ the Soviet leader says. ‘Why do you call him Geoffrey Howe?,’ enquires Mrs Thatcher. ‘Oh, that’s because he always does what I say!’

Shevardnadze cracked another joke about Mrs Thatcher:

She goes up to Heaven and God welcomes her. ‘How are you? How are things down there, my daughter?’ ‘First of all, I’m not your daughter and, secondly, you are sitting in my seat!’

Gorbachev told a story about a man who decided to change jobs and chose work in a toy factory. After all the pieces had been assembled, he found he had a machine gun. This was a subtle way of pointing out to the US president that in the Soviet Union appearance is not always reality.

Mrs Thatcher was famous for her dress sense, from her colourful power suits to the formidable handbags and pristine strings of pearls. On one occasion, visiting the Kremlin in winter, in felt boots, her Special Branch bodyguard was observed by KGB security to have bulging pockets which they assumed was ‘impressive weaponry’. The bodyguard waited until Mrs Thatcher had moved into the warm and then pulled out a pair of high heels for her to change into.

Although President Mitterrand regarded Reagan’s belief in SDI as bordering on the mystical, he maintained a hard line on France’s nuclear deterrent: it was non-negotiable, and the French Parliament even voted to upgrade their armed forces. In Moscow in April 1987, Mrs Thatcher also confirmed her belief in nuclear deterrent. In December 1987, Gorbachev dropped in on Mrs Thatcher en route to the Washington summit to sign the INF treaty. Geoffrey Howe, the British foreign secretary, was very impressed by their work rate and compared them to two star Stakhanovites (exemplary Soviet shock workers). Gorbachev’s first extended official visit to Britain, in April 1989, found Mrs Thatcher passionately interested in the development of perestroika. When Gorbachev commented that many in the West were having doubts about it, she brushed this aside and assured him that all in the West were enthusiastic about it. (This was pure fiction!)

After visiting France and Britain, the two Western European nuclear states, it was time for the Soviet leader to visit West Germany in June 1989. The Germans had been feeling left out of Gorbachev’s diplomacy. When Chancellor Kohl saw Gorbachev at Chernenko’s funeral, the new Soviet leader enquired where the Federal Republic was drifting. He used the verb driftovat, to drift, which is not to be found in any Russian dictionary. Kohl was probably the first Western leader to be treated to such neologisms – Gorbachev loved to pepper his remarks with newly mastered English expressions. Kohl found the Soviet president’s communicative skills brilliant and attempted to pay him a compliment. Unfortunately, he likened him to Joseph Goebbels, the silver-tongued Nazi propaganda chief, which soured relations for a while. This led Helmut Schmidt, the ex-chancellor, to offer this comment about the monoglot Rhinelander: ‘I think there are still two or three fields in which he still needs a lot of education: international affairs, arms control and military strategy, and economics and finance.’ In July in Paris, Gorbachev told the French the post-war era was over, and at the Sorbonne, he underlined that pure intellect without morality constituted a terrible danger. He was in Helsinki in October and then he went to Italy. The reception he received in Milan was the most emotional of his career and was feted everywhere as if he had arrived from Mars. On 1 December, he was the first Soviet leader to enter the Vatican and informed the Polish Pope John Paul II that democracy was not enough: morality was also essential. The pope spoke Russian with him for a while and assured him that he would not do anything to undermine perestroika. When Gorbachev thanked him in Polish, the pope corrected his Polish and was then invited to visit the Soviet Union.

You know, I changed things in Stavropol krai and that pleased me a lot. I thought I knew how to do it, so when I arrived in Moscow I thought I’d do the same but on a bigger stage. Then I realised, as regards appointments and personnel, you cannot even move one single person because the system (sistema) is so tightly knit and interdependent. I was really in despair.

—Gorbachev

The oblast Party leader was a king; the republican Party leader was a tsar; and the general secretary was practically God’s equal.

—Gorbachev

The main priority for Gorbachev was raising living standards. One of the reasons for the ousting of Khrushchev in 1964 had been food shortages. The share of the budget accorded agriculture increased from 16 per cent to 18 per cent and then to 25 per cent in 1985, and food was heavily subsidised. Andropov cancelled increases in bread and other food products at the last moment, in January 1983, because he feared social unrest. Billions of dollars were spent annually on importing grain and other foodstuffs.

Andropov lamented this and told the Central Committee on 22 November 1982 that the country had become accustomed to such purchases.

It became an automatic sort of procedure: we start to buy grain abroad every year; and we got butter from somewhere else, milk from somewhere else again. Of course, you will understand that they haven’t given us all this because they thought we had beautiful eyes. Money is demanded. I don’t want to scare anyone but I will say over recent years we’ve wasted billions of gold roubles on such an expensive thing.

What solution did Andropov offer? None. This analysis was so bleak it was not published. Unfortunately, the world prices of gold and diamonds began to fall as did Soviet oil output. Nonetheless, by the mid-1980s, the South African company De Beers was paying the Soviet Union about a billion dollars a year for high-quality diamonds. On the other hand, Soviet propaganda hammered any businessman who traded with South Africa under apartheid!

On 18 January 1983, Nikolai Ryzhkov, CC secretary for the economy, was scathing about the fulfilment of national plans to fellow CC secretaries:

Of course, it’s said that the plan had been fulfilled but that won’t be the truth because it is the corrected plan that has been fulfilled whereas the plan envisaged by the national economic plan has not been fulfilled. This is how we get a situation here where we ourselves create disinformation.

(Service 2015: 55–6, 58)

The concept of a socialist market economy surfaced in 1984. There was talk of promoting co-operatives and individual labour activity. Gorbachev took part in many discussion groups, but his contributions were marked by a lack of clarity and understanding of economics. This was his Achilles’s heel and like Mao, he could not comprehend the dismal science.

Everyone agreed that economic reform was necessary and even Marshal Ogarkov had reached that conclusion, but the problem was how to implement it. The gulf between labour productivity in the Soviet Union and the US had been narrowing until 1973 but afterwards it began to widen. This was due to the information revolution in the US (computers, etc.) which the USSR was slow to emulate. The Soviet economy began to slow down in the mid-1970s. Growth between 1981 and 1985 was zero, according to Abel Aganbegyan, one of Gorbachev’s leading economic advisers, but he only reached this conclusion in 1989.

The first reform was uskorenie (acceleration), the brain child of Abel Aganbegyan. Only about 15 per cent of the capital stock was up to world standards. A mere 5 per cent of exports went to capitalist countries so retooling industry became the goal. However, the investment required cut investment to consumer goods industries. The results were meagre. The next move was to combat alcoholism. This noble goal had two main drawbacks: one was the hole in the budget which would result as booze was the main source of revenue for the state, and the other was that the male population liked its vodka. My own experience revealed that one cannot separate a Russian from the bottle. Psychologically it turned males against Gorbachev and his reforms, but the female population applauded but that had little impact in such a male-dominated society.

The name given to the new economic policy was perestroika or restructuring. The goal was to rethink, reorganise and restructure the way things were done, and it was to apply to all aspects of activity. Because the economy was not taking off, Gorbachev concluded that party and government officials were holding it back. They were preventing the creative potential of workers bearing fruit. So glasnost was launched and it permitted ordinary people to criticise their bosses. This would kick-start progress, but this was a complete misreading of the reasons for the failure of perestroika to produce quick results. The main reason was that enterprises did not regard perestroika as beneficial.

The explosion at reactor number four of the Chernobyl atomic power station at 1.26 a.m. on Saturday, 26 April 1986, exposed the limits of glasnost. Gorbachev was told at 5 a.m. and a special commission of top scientists were sent to the site but forwarded no information for two days. (The first nuclear power plant to register the explosion was the facility at Forsmark, in Sweden. At first, the personnel thought that the source was their own plant, so high was the reading!) All 47,000 inhabitants were evacuated from Pripyat, 3 km from the plant, on the afternoon of 27 April, but by then they had been exposed to radiation for forty hours. A short item appeared on the evening of 28 April on Soviet television but it gave no indication of the seriousness of the catastrophe, and the May Day parades in Kiev and other cities went ahead – all within the zone of contamination. On 2 May, everyone was evacuated from the village of Chernobyl, 7 km from the plant.

Another explosion in reactor number two was possible as radioactive magma was seeping through the cracked concrete floor. If it came into contact with the water table underneath, an explosion at least ten times as powerful as Hiroshima would occur. On 13 May, thousands of miners were ordered to dig a tunnel in the sand under the reactor in order to pour in concrete to prevent seepage. Finally, on 14 May, Gorbachev appeared on television to tell his fellow citizens what had happened, but his delivery was hesitant. The fact that it had taken him eighteen days to decide to inform the public angered many. Untold thousands of people had been unnecessarily exposed to radiation due to the refusal of the Gorbachev team to act immediately. Chernobyl demonstrated to some citizens that Gorbachev was a bumbling leader who was unlikely to lead the country forward. Politburo minutes even revealed that plans to cover up the nuclear accident had been discussed. This tactic had worked when an explosion at the Mayak nuclear facility in the Urals in 1957 caused a nuclear catastrophe almost as serious as Chernobyl.

Thousands of troops were drafted in to ‘liquidate’ the problem of Chernobyl. In September, radioactive graphite had to be removed by hand from the roof of the reactor, but a man could only work forty-five seconds due to the radiation. By November, the reactor had been sealed in a huge concrete and steel sarcophagus. Chernobyl had cost seventeen billion roubles but also thousands of lives. The heroes were the firefighters and soldiers who gave their lives to save their country and Europe from an unimaginable nuclear catastrophe.

Chernobyl dashed hopes about socio-economic acceleration. It was a water-shed, and the culture of secrecy and lack of personal responsibility had to be tackled. Gorbachev made clear that politicians and scientists at lower levels had been incompetent and mendacious. Glasnost expanded rapidly, and Gorbachev used terms such as ‘socialist pluralism’ and the ‘pluralism of opinion’. It was beginning to take on aspects of the Prague Spring.

Chernobyl added urgency to the need to reach agreement on nuclear weapons. Gorbachev, in a conversation with George H. W. Bush on 10 December 1987, mentioned that if nuclear power stations in France or elsewhere were destroyed, it could lead to nuclear war. The idea that one could do something after the beginning of a nuclear conflict was nonsense. If foreign ministers could not reach agreement in arms control negotiations, they should be fired (Service 2015: 189).

There was no coherent pattern to the economic reforms which were introduced. One instance was the law on co-operatives and individual labour activity, in 1986. It was followed by legislation which criminalised money grubbing, unearned income (letting a room in one’s flat, for example) and living above one’s means. Often legislation would afford enterprises greater autonomy in production and distribution of goods, but the second part of the same legislation restricted these concessions. Ministries were downgraded but they had arranged intersectoral transfers, financed research and development, trained personnel and lobbied the centre on behalf of their enterprises.

The most radical reform so far was the law on the state enterprise of July 1987. It promoted self-financing and self-management. Workers could elect the director and other personnel, including foremen. If they disagreed with management, they could dismiss it and elect new management. Government and party officials could no longer give orders to enterprises. Of all the economic reforms this was the most disruptive. Self-financing did not make a lot of sense without a comprehensive price reform. As a consequence, perestroika began to run out of steam by the end of 1987.

The conference, in June 1988, was a great leap forward towards democratisation. The USSR Congress of People’s Deputies (CPD), extinct since Lenin’s day, was resurrected. Fifteen hundred deputies were to be directly elected in multi-candidate elections and 750 nominated by social organisations, such as the party and Komsomol. The CPD would elect from its members a Supreme Soviet of 400 members. They would be full-time law makers. This move transformed the role of the chair of the USSR Supreme Soviet, which hitherto had been a more or less decorative post. The present holder was Andrei Gromyko but Gorbachev, wanting the post for himself, pushed Gromyko into retirement. A Belarusian, Gromyko spoke beautiful Russian and had a keen sense of humour but never displayed this in public. He followed the Russian tradition that if someone smiled all the time, he was regarded as an idiot. One has to remember that he had a hard taskmaster, Josef Stalin, who believed that a Soviet diplomat should be feared and not loved. ‘Grim Grom’ (foreign minister from 1957 to 1985) will go down in history as Mr Nyet (Mr No). He would have achieved much more had he been more flexible but, after all, Russians do not bargain but negotiate. He was to rue the fact that he had helped make Gorbachev party leader.

The conference highlighted the fact that the party had split into various factions. Those who wanted to proceed slowly were probably in the majority, and one of the critics was the writer Yury Bondarev. He did not like what had happened over the previous three years and likened perestroika to a plane which took off and had no idea where it was going to land.

Yeltsin was also quite a performer. He proposed that those members of the Politburo who had been there under Brezhnev resign because they were responsible for the mess the country was in. He attacked the party nomenklatura’s privileges: their special polyclinics, special shops and the like. There ‘can be no special communists in the Party’, he thundered, and the little people loved it. He called for multi-candidate elections to all party posts and then he turned cheeky. Would the delegates rehabilitate him by removing the charges made against him at the October 1987 plenum? He would prefer it now rather than fifty years after he was dead. He was showered with abuse.

He also proposed the privatisation of public property. But who could buy this property? Party bureaucrats, enterprise managers, those who had done well from the shadow capitalist economy, the black market rich, the KGB – these groups stood to do very nicely from the rise of Yeltsin. Boris presented himself as the champion of the Russian Federation as it did not have its own Communist Party, Academy of Sciences and so on and this amounted to discrimination. Russian nationalists flocked to his colours.

An even more radical reform was the decision to remove the party from the industrial economy (agriculture remained a party responsibility until the collapse of the Soviet Union). Party secretaries had been the glue which kept the planned economy together. Party First Secretaries, almost always engineers – except in oil regions where they were geologists – were recruited from successful enterprise managers. He had four main functions:

Who was to take on these responsibilities? The local Soviet, but it had no department of industry and therefore had no expertise in such matters. So a vacuum began appearing at the local level. Enterprises gradually paid less attention to the centre and began forming trusts and associations, and this had an important side effect in non-Russian republics: the growth of nationalism.

A popular ditty made the rounds:

Sausage prices twice as high

Where’s the vodka for us to buy?

All we do is sit at home

Watching Gorby drone and drone

Another caustic comment was: ‘How do you translate perestroika into English?’ ‘Easy. Science fiction.’ A cartoon depicts an enterprise director dictating a telegram to Moscow. ‘Have successfully implemented perestroika. Await further instructions.’

The Soviet Union became more and more dependent on international markets for grain and food imports. The first large grain imports were in 1963, and in 1984, they had risen to forty-six million tonnes, costing $25 billion in 2000 prices, and in 1985 they were 45.6 million tonnes, costing $22.5 billion. Gold was also sold to raise the money to pay for these huge imports. The grain was for human, cattle and poultry consumption. Cattle were raised in huge complexes (following the US example) but Soviet farmers could not supply enough feed grain and the same applied to poultry production. The Soviet Union began to run up a hard currency debt in 1974, and it rose inexorably afterwards. By 1985, Soviet debt was $22.5 billion but, if Eastern Europe is added, it became $115.7 billion. (According to Gaidar [2007] in 1988, Soviet debt had risen to $41.5 billion and all socialist countries to $205.7 billion.)

A law on cooperatives was passed in May 1988 but most of them were set up in state enterprises. They mushroomed and by mid-1989, the number of workers in cooperatives had risen to 4.9 million. Wages in cooperatives were at least double those in state enterprises and in early 1991, six million were working in cooperatives. They often raised the ire of the general public as enterprise goods were simply sold at a handsome profit. They were also used as a cover for drinking, as tea cups were distributed but then filled with vodka. Cooperatives were useful channels for laundering currency acquired through bribery and corruption.

Legislation in July–August 1988 permitted the Komsomol to engage in foreign economic activity. In other words, the Komsomol elite could set up scientific and technical centres and undertake research for domestic and foreign firms. Legislation in November 1989 permitted an enterprise to purchase, wholly or partially, property it was renting. This, in effect, privatised property and allowed management to acquire valuable assets at low prices.

In 1985, the six military members of the Politburo retired and, among the new talent promoted was Deputy Prime Minister Li Peng, who had studied hydraulic engineering in the Soviet Union. Hainan Island, off the south east coast, became an SEZ to produce, among other things, rice and sugar cane. Guangdong province became, in effect, an SEZ; other coastal cities followed and Shanghai itself could attract foreign investment. Two Chinese economies emerged: the SEZs based on foreign capital and expertise and becoming enormously prosperous, and the rest of the economy where living standards lagged far behind. Zhao Ziyang, the prime minister, became enamoured of the scientific technical revolution and after a visit to the US became even more excited by the potential of technology to change the world.

Huge state projects, such as the Shengli oil refinery, were launched but local officials expected a cut to turn a blind eye to irregularities. It was in their interests to promote business in their region and tax evasion became the norm. Deng said on American TV: ‘To get rich is glorious. To get rich is not a sin.’ (He is also credited with another aphorism: ‘It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white as long as it catches mice.’ What he actually said was: ‘It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or yellow.’)

Because unemployment was not permitted to exist under socialism, surplus labour, mostly young people, was sent to the countryside from the 1950s onwards. This ended with Mao’s death and they then returned to the cities. There were over twenty million of them, and they accounted for about 10 per cent of the urban population. Few of them could find work and they began blocking railway lines, surrounding government buildings and the like. In November 1979, the government was forced to legalise individual economic activity and a person could now become an entrepreneur. Pressure from below – fear of mass protests – had again won the day. Two years later, the party and government declared that private entrepreneurship was a ‘necessary complement’ to the socialist economy. This opened the floodgates to capitalism in cities and towns. During the 1980s, the authorities discriminated against TVEs and individual activity, and it was only in 1992, when capitalism was officially recognised as part and parcel of socialism, that discrimination ended.

Students wanted more democracy, which Deng was determined to deny them. In January 1987, Hu Yaobang resigned as secretary general of the party. He had favoured dialogue and some movement towards democracy but he refused to stand and fight for his convictions. Zhao Ziyang took over the top party post, and a battle developed between hardliners and reformers over who should become prime minister. Eventually Li Peng got the nod. A conservative, dour comrade, he was an uninspiring choice.

In April 1989, Hu Yaobang suffered a heart attack at a Politburo meeting and died a week later. Hu was extremely popular with intellectuals and students, and he was revered as that rara avis, an honest communist. During student demonstrations in 1986, he had sided with the students. A list of political demands was handed to the country’s parliament, and they included calls for freedom and democracy. At another demonstration there were shouts of ‘Down with the Communist Party!’ Deng declined to visit Hu in hospital and he became a target for the demonstrators.

Student protests were normal but this time it was different, as the public joined them, and the leaders were stunned by the number of Beijingers who joined the protests. The railways allowed masses of students to travel free to Beijing. Deng became exasperated at the extent of the protests which spanned 130 cities.

On some days, there were about a million protesters on Tiananmen Square. A policeman, told by an old lady not to touch the students because they were ‘our’ children, told her: ‘If it weren’t for this uniform I would join them.’ Li Peng, the prime minister, told Deng that the protesters wanted to overthrow the regime. One of the golden oldies, the Party Elders, called the students ‘bastards’.

In the midst of this crisis, the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev arrived. This was not his first attempt to improve relations with the Middle Kingdom. When Li Peng was in Moscow for Chernenko’s funeral, he had rejected the olive branch extended by the new Soviet leader and stressed that China would never accept subordinate status to the Soviet Union but did not rule out an improvement in relations. He returned in June 1985 to sign an agreement on scientific and technical cooperation. When he visited again in December 1985, Gorbachev stressed they had a common interest in opposing SDI. He wondered why China supported America’s policy in Afghanistan and assured Li that Moscow had no interest in causing trouble for China in Vietnam. Li made it clear to him that China would not accept the ‘little brother’ status and there would be no normalisation of relations until the USSR changed its policies in Afghanistan and Cambodia. Moreover, he was sharply critical of Moscow endorsing Vietnam’s military presence in Cambodia. On a more positive note, a visit by Deputy Prime Minister Yao Yilin in December 1985 saw negotiations on arms control and the signing of a bilateral trade and economic co-operation.

Gorbachev’s visit had been prepared by Shevardnadze who had visited Beijing and Shanghai in February 1989. In the Chinese capital, Shevardnadze proposed the normalisation of relations and therefore a visit from Gorbachev would be welcome. He met Deng in Shanghai who advocated better relations and assured Deng that there were no Soviet troops in Afghanistan in false uniforms. Deng made clear there could be no peace in Cambodia until all Vietnamese troops had been withdrawn. Shevardnadze even hinted the Soviets might stop providing aid to Hanoi. What made Deng angry were the machinations of the Vietnamese to set up an Indochinese Federation, dominated by Vietnam. He even brought up the territories lost to Imperial Russia during the nineteenth century: ‘There will come a time when China will perhaps restore them to itself.’ Stung by this, Shevardnadze even asked the Politburo on 16 February to consider returning some territory around Vladivostok (it had been taken as recently as 1860).

The depth of Chinese feeling about the unequal relationship with Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union was brought home to me in an interview, in August 1988, with a member of the Central Committee of the CPC who had studied in the Soviet Union. He delivered the first two sentences in Russian and then reverted to Mandarin. He proceeded to launch a violent tirade against the Russians for the way they had demeaned, insulted and taken advantage of the Chinese, beginning with the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, the first treaty signed by the two countries. He went through all the subsequent treaties, ending with the one which Stalin had imposed on the People’s Republic in 1950. I was warned never to trust Russians (not Soviets) as they were cheats, thieves, dishonourable and disreputable people.

To put it mildly, Gorbachev was not impressed by China’s reforms and on 29 September 1986 informed his aides:

The Chinese have developed agriculture on a private basis. They have achieved stunning success but there should not be euphoria as if China had resolved everything. But what next? They don’t have fertilizers, technology or intensive methods. We have all of these but we have to unite these with personal interest. This is our problem. This is where we can insure a burst forward. Ilich (Lenin) tormented himself about how to unite the personal interest with socialism, and this is what we have to think and think about.

Gorbachev failed to appreciate that socialist agriculture had failed in China and that was the reason why private or capitalist agriculture had re-emerged.

He told Anatoly Chernyaev, in August 1988:

I don’t understand all the fuss about China… Yes, there is everything on the shelves in the shops but nobody is buying. It is a capitalist market. And the law of that market operates in such a fashion that prices are inflated to the point that everything lies around on shelves and when the goods go stale they sell them off cheaply.

(Service 2015: 380–5)

What an extraordinary analysis! If anyone needs evidence that Gorbachev did not understand economics, this is it. I spent two months in China in the summer of 1988, mostly in Beijing, and can testify that goods moved off the shelves. There were two currencies: the hard and soft yuan, and one could buy choice goods with the former. There was a Friendship Store for foreigners but only hard currency was accepted. It is true the quality of the goods was not very high and this extended to the construction industry. I stayed with a middle-class family in a new flat and one can only say the quality of workmanship was very low. On the other hand, one had to be at a bakery at 6 a.m. to get the bread one wanted in Liaoyang, in central China. It did a roaring trade in wedding, birthday and other cakes which were as delicious as anything one could buy in London. I asked what the secret was: all the flour was imported.

Students were enthusiastic about Gorbachev’s reforms and many wanted their own Gorbachev. Some were fasting in Tiananmen Square in the hope he would intercede on their behalf and they and their supporters cursed Deng. The Soviet leader was keen to repair relations with the Middle Kingdom, and some of Deng’s speeches were published in Russian and favourably reviewed in Pravda.

On 16 May, Gorbachev arrived in Beijing and was met by Deng – the welcoming ceremony had to be held at Beijing airport because Tiananmen Square was full of students – who had warned him there was to be no hugging and kissing. He then proceeded to give him a lecture on Russian imperialism: 1.5 million km2 had been stolen from China, no one would forget this, and there was no point in speeding up the normalisation of relations between the two Communist parties. When he met Li Peng, the prime minister showed no interest in more trade but concentrated on issues which divided the two countries. He regretted the depredations Japan had wrought in China during their occupation from 1937 to 1945 but said that pragmatism dictated economic relations as Japan was an advanced industrial country. It was high time that the Soviet Union and China agreed on their frontier. Gorbachev responded by saying he would like to demilitarise the frontier. He then met Zhao Ziyang, party general secretary; the discussion was very open, and it was clear that the Chinese Party boss wanted to go down the same route as the Soviet Union. But Deng did not, and hence Gorbachev was an unwelcome guest. However, he was able to make a speech in the Great Hall, on Tiananmen Square, in which he highlighted the fact that 436 short- and medium-range nuclear weapons would be destroyed in the Soviet East. He proposed that the Soviet railway network could form a new Silk Road by transporting Chinese goods to Europe, and he ridiculed Western commentators who saw Soviet and Chinese reforms as leading to the restoration of capitalism. Gorbachev asked China to provide desperately needed consumer goods and would be paid in raw materials, and he also requested a loan which was agreed.

Shevardnadze held talks with Jiang Zemin, Shanghai Party boss and Politburo Standing Committee member, who informed him China was willing to act as intermediaries to resolve the conflicts in South East Asia. Gorbachev was taken around a modern factory in Shanghai but was not impressed. It became clear that Deng and Li had little interest in expanding trade with the Soviet Union now that capitalist countries were investing in China. Gorbachev’s inability to recognise that China was modernising rapidly was reflected in his comment to James Baker, in late May 1989, when he informed the American that China’s scientific and technical capacity would soon hit the buffers (Service 2015: 387–8). Gorbachev held to the Western capitalist view that successful modernisation had to be accompanied by democratisation. What he had not realised was that China was undergoing economic democratisation but not political and that was the secret of its success.

Annoyed at Zhao’s comments to the Soviet leader, Deng called a meeting on the morning of 17 May. He informed the leadership that the students’ goal was to set up a ‘bourgeois republic on the Western model’. Multi-party elections would cause chaos like the ‘all-out civil war’ the country had experienced during the Cultural Revolution. ‘You don’t need guns and cannons to have a civil war; fists and clubs will do just fine’ (New York Times, 6 January 2001). National stability came before democracy, and the party thought that if it retreated any further it was finished. Deng informed them that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) would be brought in to restore order and martial law. Zhao Ziyang disagreed and asked Deng to rescind the martial law decision whereupon Deng reminded him that the minority submits to the majority. Rumours spread about the imminent declaration of martial law and over a million appeared on the streets. They supported the hunger strikers and called for Deng to go. Zhao and Li Peng went out to meet the students but Zhao conceded tearfully they had come too late. Deng was furious at Zhao’s tears and words, and martial law was declared on 20 May.

Troops began moving into the city, but about two million Beijingers set up road blocks with buses and lorries and prevented them reaching their destinations; some units went over to the demonstrators. The troops retreated to their bases, and it looked as if China was sliding into anarchy.

On the night of 3–4 June, troops moved forward, encountering the usual road blocks. This time they opened fire and killed many ordinary citizens in the western parts of the city. In the bloodletting that night, most deaths occurred outside Tiananmen Square. The crowd’s anger was vented on the soldiers and some of them were lynched. The Goddess of Democracy, a huge statute erected by the students, which had stood facing Mao in Tiananmen Square, was flattened by tanks. This symbolised the squashing of hopes for democracy for decades to come. Demonstrators in sixty-three cities across China protested against the slaughter of the demonstrators in Beijing.

Figure 13.5 Deng Xiaoping

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540 USA, US News and World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, LC-DIG-ppmsca-09796.

The official death toll was put at 200 but the most realistic was 775. Anatoly Lukyanov informed the Soviet Politburo, at its meeting on 4 October 1989, that the real number of casualties was 3,000. Gorbachev commented: ‘We must be realists. Like us, they have to defend themselves. Three thousand – so what?’ Deng Xiaoping’s comment was as chilling: ‘You call this a slaughter? This is a petty matter compared to what China saw not so many years ago.’ It is difficult not to conclude that Deng was also taking revenge for the humiliation which he and his family had suffered during the Cultural Revolution.

The crackdown was a disaster for the demonstrators but even more for Deng as foreign investors could not get out of China fast enough. President Bush announced a cessation of weapons sales to Beijing, worth $600 million, as did the European Union, and the World Bank said it would end lending to the Middle Kingdom.

Jiang Zemin took over as party leader and reverted to pre-reform language. The entrepreneurs, who had benefited from reform, had sided with the students so they had to be closed down. Private companies were not to be permitted to compete with SOEs. Farmers were encouraged to go back into communes. Party secretaries reappeared in factories and farms and claimed precedence. Red had taken over from expert and profit was a dirty word again.

Deng took a back seat but was still acknowledged as the paramount leader. The period after Tiananmen Square was characterised by a fierce struggle between the conservatives and those who wanted to continue with market reforms. The execution of the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu and his wife in December 1989 underlined the importance of military support as Ceauşescu had fallen after the army deserted him. The PLA cleansed its ranks of those regarded as unreliable with some being court-martialled, and the military budget was cranked up 15 per cent.

The increasing chaos in the Soviet Union was another warning of the consequences of not keeping a tight rein on political reform, and Jiang Zemin even called Gorbachev another Trotsky. He had studied in the Soviet Union and was as near to a technocrat as the party had. He surprised Richard Nixon on a private visit in 1989 by reciting the Gettysburg Address in English and was well-versed in Western classical music. He realised that the only course for China was to improve relations with developed countries as only they could provide the technology the country needed. This would permit the Middle Kingdom to become deeply embedded in the world economy and play a role in key international institutions. In foreign affairs, he was well served by the astute Qian Qichen, and in economic policy by Zhu Rongji, who later became prime minister.

Deng met military leaders and won them over so the PLA would now protect his reforms. In January 1992 he set off, accompanied by his daughter, on a southern tour which he disguised as a family holiday. He made for the Shenzhen, one of the SEZs, and was given a hero’s welcome, and also went to Zhuhai and Shanghai. Deng said that without economic progress, the events of 3–4 June would have resulted in civil war. China had to move forward boldly and assimilate all the fruits of civilisation, including those of advanced capitalist countries.

In 1992, the constitution was amended to stipulate that the head of the party and the prime minister could only serve two five-year terms in office as no one wanted another Mao. At the 14th Party Congress, in October 1992, Deng underlined the fact that the party could not be challenged and that China would not adopt a real multi-party system. There are eight other political parties, but they are dubbed ‘flower pot parties’ as they perform merely a decorative function.

The battle between those who wanted to retain a centrally planned economy and those who favoured moving to a market economy lasted from 1978 to 1992, when the country moved to a market economy with Chinese characteristics.

An important factor was that the US opened its doors to Chinese goods, and China had an advantage over the Soviet Union in that overseas Chinese began to invest and added their know-how. Taiwan also joined in. Suzhou, near Shanghai, is a modern city and was built in collaboration with Singapore. Deng’s attitude to foreign affairs was succinct: ‘Bide our time and conceal our capabilities.’ Hence Chinese foreign policy consisted of not interfering in the domestic politics of any country. China, instead, concentrated on trade as a way of expanding its influence. For instance, China signed 1,395 bilateral treaties between 1973 and 1982. Almost all of them were commercial, and the Middle Kingdom did not enter into any military alliances. Instead, it concentrated on building up the strength of the armed forces, and almost all the modern hardware came from the Soviet Union. The Chinese tactic was to order, say fifteen MiG fighters, but only take delivery of one. Then they copied it – reverse engineering – and cancelled the order for the other fourteen. They also did this with trade in civilian goods. A German company delivered a state-of-the-art printing press, and when the representative visited again he was shown a replica of his press. SEZs naturally involved technology transfer as did joint ventures with foreign firms. Thousands of Chinese students went to the US and Europe to study. The main subjects were science, engineering and computing. At Imperial College, University of London, the only arts subject Chinese study is the Russian language.

Only two communist regimes in Europe were endogenous: Yugoslavia and Albania. All the others – in Poland, the GDR, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria – were exogenous. Without the Red Army, the communists would not have acquired and retained power. Czechoslovakia was in between. It was an endogenous revolution in February 1948 but an exogenous force – the Soviet Army – kept it in power.

Had it not been for Big Brother in Moscow, the communist regimes would have been swept away. Experience was to show that once communism collapsed in other states, Yugoslavia and Albania would go the same way.

So what would the new comrade in Moscow do? Having visited Czechoslovakia after the suppression of the Prague Spring, Gorbachev was well aware of the depth of hatred felt by most Czechs and Slovaks towards the Soviet Union. One of his university fiends, Zdenék Mlynář, was able to report to him on the temperature of relations. Gorbachev took it for granted that Eastern Europe, once it had chosen communism, would remain communist. The debate was about the type of communism which could evolve.

Eastern Europe was secure behind the shields of the Soviet Army. The US and its NATO allies did not contemplate starting the Third World War over Bratislava or Sofia, and the Warsaw Pact had troops everywhere except in Romania and Bulgaria.

Gorbachev, in March 1985, told Eastern European leaders that the Soviet Army would no longer be used to resolve political conflicts on their patches. What were they to make of this? They were used to communist speak: the boss said one thing and meant another. All this talk of communist states being equal and responsible for their own affairs was probably eyewash. Anyway, it was important that the population of Eastern Europe continued to believe that if they stepped out of line, Ivan would come marching in. Then at the June 1988 Party Conference, Gorbachev reiterated this view: ‘to reject freedom of choice is to oppose the objective movement of history itself. That is why the policy of force in all its forms has historically outlived itself.’ At the United Nations in December 1988, he talked about the universal right of choice and claimed there were no exceptions.

Erich Honecker did not like what he saw in the Soviet Union. He was known as Erich ‘Don’t Tell Me Any Bad News’ Honecker. Erich informed Gorby there was no need for perestroika in the GDR and it should be dropped in the Soviet Union. Alarmed at the contagious effect of information about the political and economic changes in the Soviet Union, the GDR leader took the unprecedented step of banning Sputnik which was a popular Soviet magazine. The Soviet ambassador responded by distributing it from the embassy!

Gorbachev was aware of the fragility of the Eastern European economies. On 23 October 1986, Nikolai Ryzhkov presented a bleak report to the Politburo. Poland was knee deep in debt and Hungary was looking into the abyss. No economist there thought the solution was integration with the Soviet economy – they were all looking westwards for salvation. Another analyst concluded that Warsaw Pact countries would collapse in 1989–90. Gorbachev waxed eloquent about the desire of the region to undertake perestroika, but this was a myth. In January 1989, Gorbachev even wondered what would happen if Hungary applied for membership of the European Economic Community (the European Union after 1993). He conceded that the Soviet Union could not provide any more aid, but Eastern Europe needed new technology, and inevitably it would look westwards. The Soviet military was also feeling the pinch, and its budget did not increase in 1989, the first time this had happened since the 1920s (Service 2015: 316, 367). So by 1989, the Soviet Union had accepted that the region could decide its own future.

There were two main reasons why Gorbachev did not want to intervene militarily in Eastern Europe. The first was that if he did, it would provide a precedent for the use of military force in the Soviet Union. Because most of the political establishment, the KGB and the military wanted force to be used at home, it would be impossible to resist. The other reason was economic. Military intervention in Eastern Europe would be followed by Western economic sanctions, and vital imports of grain, foodstuffs, fodder and technology would be embargoed. In 1989, the Soviet Union depended more on the Western world than vice versa, and so sanctions would weaken the Soviet economy. Under such a scenario it is difficult to imagine Gorbachev surviving.

Had Eastern Europeans known that Gorbachev would remain in office and that the Soviet military would not intervene, they would have blown the communists away before 1989. They were delighted by perestroika and the reforms it brought in. Taking the party out of the industrial economy, having multi-candidate elections to parliament, the laws on cooperatives and individual farming and the setting up of new banks were all Eastern European aspirations. They all wanted their own Gorby.

The rise of Solidarity in 1980–1 held out hopes for radical reform in Poland, but the fact that the Polish military remained loyal to the Polish United Workers’ Party meant that the movement was suppressed and driven underground. Wojciech Jaruzelski knew that if the military remained loyal, he was secure in office. That was his first priority, and his second priority was to effect gradual change. In April 1984, Gromyko delivered a dismal report on Poland and concluded that the country was looking to the West for economic salvation. He criticised Jaruzelski for promoting the emergence of a kulak class in the countryside; Ustinov thought that the Polish military was too passive and, anyway, they were all sons of Solidarity. One solution was to give Jaruzelski a stiff talking-to!

Hungary was an obvious role model for Poland and the Hungarians had their New Economic Mechanism, but there was nothing similar in Poland. Reform economists worked with the Hungarian government, but this was not the case in Poland as all reformist economic thinking took place outside the party. In 1988, price rises afforded Solidarity activists the opportunity to lead strikes, and after a strike by coal miners – the elite of the working class – the government managed to lose a vote of confidence in the unreformed Polish Parliament or Sejm. Mieczysław Rakowski, a more open-minded communist, became prime minister.