The US, in 1945, was a global economic and military power, and this combination made it possible for the American political leadership to begin dreaming of a new world order which would mirror American values. ‘Man by nature is violent’ is an old adage. There were over 2,000 civil wars in China before Qin Shi Huang established the first modern world state in 221 BC, ruling 90 million subjects or one-third of the world’s population. The Roman Empire lasted a half millennium and had always to defend its territory and, if possible, extend it. The Religious Wars in Europe between Roman Catholics and Protestants lasted almost a century and a half. Spain, France and Britain fought one another to dominate the continent afterwards. Great empires rose and fell. Russia expanded to the Pacific in 1639; the Russians even acquired Alaska and had a fortress in California, Fort Ross (a corruption of Rossiya).

In 1945 the Americans thought it would be possible to put an end to the constant warfare and conflict which had blighted human history. If the major world powers – the US, the Soviet Union, Britain and China – could come together and agree a new world order, peace could reign. Sometimes dubbed the four policemen, they could patrol the planet and snuff out any conflict which threatened to disrupt the peace. The problem with this vision was that the four policemen were not equally strong. Britain and China were bankrupt, and the Soviet Union would take years to recover its former strength, which left the US as the dominant power. The concept of world government was a thinly veiled attempt for the US to take over the world. At least, that is how the other powers saw it. Because politics is about power, this vision was dead in the water from birth. Not only Britain was bankrupt but the whole of Europe was as well.

Had the world been wholly capitalist, a modus vivendi could have emerged. War was off the agenda as reconstruction had priority. However, the main military force in Europe, the Soviet Union, was not capitalist but communist. The European Enlightenment (1650–1780) had given birth to a revolutionary idea: man could shape his own destiny and had no longer to be subservient to God. In other words, man became God, and a product of this thinking was Marxism. Marx, following Hegel, put forward the intoxicating vision of the perfection of humankind, and it was not only possible, it was certain. This vision eliminated the market economy which, in Marx’s view, was the source of all human evil because inequality led to the formation of classes. There were two main classes, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. The workers produced the wealth, and the factory and landowners – the capitalists – expropriated it. So the solution was simple: abolish capitalism and the proletariat could rule the world. The first stage would be socialism, during which there would be inequality; this was because some would contribute more than others to human wealth. The second, higher stage, communism, would abolish inequality, and harmony would reign – conflict would be a thing of the past – and everyone’s needs and desires would be satisfied.

This powerful narrative won many adherents worldwide. The message was quite simple: all the ills of the planet emanated from capitalism – the US was the leading capitalist state – so overturn capitalism, and the land of plenty was within reach. War arose because capitalists had to fight one another for markets, so abolish markets and thereby abolish war. No wonder Washington after 1945 found it difficult to come up with a competing narrative which was just as seductive. The capitalist world could preach freedom and democracy, but the communists could respond that freedom meant that people could become rich by exploiting others and democracy was a sham as it was the rule of powerful capitalist elites.

Russia before 1917 was a land with a mission. The Russian Orthodox Church regarded itself as a repository of a long Christian tradition. The first Rome was the centre of Christianity; then Constantinople became the Second Rome; then Moscow took on the mantle of the Third Rome when Constantinople succumbed to Islam; there would not be a Fourth Rome. This mythical progression was deeply embedded in Russian religious thought. The European Enlightenment did not embrace Russia so there was no debate about separating church and state, as the Tsar fused both in his person and answered for the whole Russian people at the Day of Judgement.

The secular reaction to this was Marxism, and religion was the opiate of the people, so they had to be liberated from it and the cloying power of the Church. Marx’s ideas came late to Russia because industrialisation only got under way in the 1890s. So Russia was already half a century behind other Western European states such as Britain, France and Germany. Revisionism was creeping into Marxism there as Marx’s theories, set out in Das Kapital, were proving inaccurate. He did not bother to publish volumes two and three of Das Kapital. After his death, in 1883, it was left to Friedrich Engels, his close associate, to edit and publish them, and it is fair to say that Engels did not always understand what he was editing. So Marxism was becoming less dogmatic by the end of the nineteenth century, and a fundamentalist interpretation was difficult to sustain.

Russians embraced Marxism with a religious fervour. At long last, they could escape from their economic backwardness and join the mainstream of European and world development. Russia was behind, of course, as it had yet to achieve a bourgeois revolution – industrialists taking power – whereas the other leading European powers were already well into that phase. Capitalism had to develop until it reached its zenith, and then would come the inevitable socialist revolution when workers would seize power from their bourgeois bosses and initiate progress which would end in an earthly paradise. Russia had now joined the mainstream of human development. There was no longer a Russian problem, and there was no need to feel inferior.

When the Bolsheviks took power in October 1917 they adopted a fundamentalist approach to Marxism and rejected the revisionism of Bernstein, Kautsky and the German social democratic party. Stalin penned the history of the Communist Party, in 1938, and it was the last word on the subject, and it could not be revised or amended, except by Stalin himself. He also published the Foundations of Leninism, in 1924, after Lenin’s death which presented the basic tenets of the faith. Without the party – it was the proletarian vanguard – workers could not achieve socialism and communism. According to Stalin, the Soviet Union attained the socialist stage of development in 1936 and thereafter communism was being built.

Stalin achieved political dominance in 1929 and his power grew as time passed. According to Khlevniuk (2015), all his policies had one aim: to increase his personal security as leader, and foreign and domestic policies were two sides of a coin. The stronger the state, the stronger he became. His worldview was Marxist, he always saw problems from a class point of view, and he was strongly opposed to capitalism as it permitted the individual to act autonomously. From his point of view, everyone had to serve the state. He or she had to sacrifice all – even life – as the state could do no wrong; if harsh measures were needed, this was a function of historical necessity, and Stalin saw himself as the agent who fulfilled the demands of historical necessity.

The world outside Europe, later to be known as the Third World, was dominated by European Empires during the first half of the twentieth century. The largest was the British; then came the French, Dutch, Belgian, Portuguese, Spanish and Italian. Germany had lost its colonies after 1918. The Japanese came on the scene in the 1930s when they penetrated China. All these empires collapsed after 1945. In their place appeared a plethora of new states, many of them appearing on the world stage for the first time. Most of them were not nation states but groups of clans or tribes, but they all wanted their place in the sun and to escape from imperial influence. Because most of these states were unstable, they were fertile ground for the spread of communism. To the Soviet Union, these new states presented an unprecedented opportunity. If they adopted the Leninist brand of socialism, this would serve as the demonstration effect, and it would also subtract these states from the total of capitalist states. If the Third World turned socialist, capitalism, headed by the US, would be doomed. The Third World, the periphery for the superpowers, was to pay a high price for the Cold War as the Soviet Union and the US intervened in their own interests, not those of the locals.

The emergence of the Cold War was a slow process. It is normally dated from 1947, but all that says is that it was then out in the open. Even after the opening of the Soviet archives after 1991, it is still impossible to conclude who was more responsible: Stalin or Truman. One can plot Stalin’s actions quite closely, and something he recognised as potentially fatal for the Soviet system was close association with capitalist powers. He labelled this ‘kowtowing to the West’, and the two competing systems had to keep their distance from one another otherwise Soviet society could be infected with Western ideas. The country was weak economically and needed all the aid and finance it could get from the West, but the goal was not a rapprochement between the two competing economies. Stalin never thought of changing the economic levers which had propelled the country forward in the 1930s, and drew no conclusions from observing the rapid growth of the American wartime economy. He held to his Marxist view that the US economy would suffer recession soon after the war ended and the capitalists would then fight one another for markets. He ignored the advice of Soviet economists that the capitalist states had learnt how to run a successful economy during the war and could put this experience to good use in peacetime.

During the autumn of 1945, Stalin was exercised by the effect of foreign praise of Soviet officials. He sent a letter denouncing unnamed ‘senior officials’ who ‘were thrown into fits of childlike glee’ by praise from foreign leaders. ‘I consider such inclinations to be dangerous since they develop in us kowtowing to foreign figures. A ruthless fight must be waged against obsequiousness towards foreigners.’ There was a risk that the country would develop an inferiority complex and that Western culture would ‘contaminate’ Soviet society. In August 1946, a Central Committee resolution was published attacking Leningrad writers. Spearheaded by Andrei Zhdanov, the campaign vilified them for ‘kowtowing to the contemporary bourgeois culture of the West’. Musicians were also lam-basted. Two scientists, developing a cancer drug, were baselessly accused of passing secrets to the West and ‘servility to anything foreign’ (Khlevniuk 2015: 265–6). Hence Stalin was trying to avoid any interaction between the two competing world systems, and keeping them at arms’ length was his aim.

There were several démarches which annoyed Stalin. The Americans would not permit the Soviets to participate in the occupation of Japan, and he wanted a base in Libya which would give the Soviet Union a presence in the Mediterranean. Again the answer was no. The Western Allies dragged their feet on German reparations, and a large loan from Washington was not forthcoming. Under pressure, the Soviet Army had to leave Iran in early 1946. Stalin offered a ‘friendly’ warning to the US ambassador after Churchill’s ‘Iron Curtain’ speech in Fulton, Missouri. ‘Churchill and his friends might try to prise the United States away from the USSR.’ Stalin saw the Marshall Plan as American economic imperialism, as its aim was to draw Eastern Europe away from the Soviet Union. At the founding conference of the Cominform, Zhdanov divided the world into two camps, and comrades were instructed to stand up to ‘international imperialism’.

On the Western side, meetings proved very frustrating. An example was the foreign ministers’ conference in London in September 1945. Molotov agreed that France and China could participate in discussions about peace treaties with the defeated countries, but they could not vote on the final draft. On hearing this, Stalin became angry and demanded that Molotov rescind the agreement as he had exceeded his brief. The next day, Molotov duly reversed his approval, but he mentioned this was on Stalin’s orders which made the vozhd even more angry. He was told that this was quite unacceptable behaviour, as Stalin always wanted Molotov to play the hard man while he could come in later and make some concession to save the day.

Another perennial problem was Poland. The Soviet Army needed to pass through the country to get to East Germany so Poland had to have a government friendly towards the Soviet Union. Stalin actually used the word ‘satellite’ to refer to the Eastern European countries in a note to Molotov. Hence he regarded the Soviet presence there as non-negotiable. Security was paramount.

In December 1945, with Stalin on vacation in the south, the foreign press began speculating about Molotov taking over. Stalin sent angry telegrams to top politicians but not Molotov. He talked of ‘libels against the Soviet government’ and wanted stricter censorship.

I am convinced that Molotov does not care about the interests of our state and the prestige of our government… So long as he gains popularity within certain foreign circles, I can no longer consider such a comrade as first deputy [Prime Minister]… I have doubts about some of those close to him.

(Khlevniuk 2015: 272)

No wonder it was extremely difficult to reach agreement with Molotov. A Damocles sword was always suspended over his head, and he was succeeded as foreign minister, in March 1949, by Andrei Vyshinsky; as the latter was terrified of Stalin, he was unlikely to stray from his brief.

Stalin also cut the Soviet military down to size as he was aware that they uttered disparaging remarks about him at reunions. Marshal Georgy Zhukov was withdrawn from Germany, and some other top military officers were shot. Stalin was aware that Zhukov and General Dwight Eisenhower were on very good personal terms, so he made sure they had little contact and that the Soviet military was not permitted to fraternise with their former Allied comrades.

Stalin committed some egregious mistakes, and the greatest was the Berlin Blockade. Coming after the Prague coup, in February 1948, it was Stalin throwing down the gauntlet, and the longer the airlift lasted, the closer the US and Western Europe were bound together. Without it, there would have been no NATO or the rapid founding of the Federal Republic of Germany and its integration in European political, economic and military structures.

Another blunder was to turn down the invitation to join the IMF and World Bank, and this cut off badly needed credit. The Marshall Plan was designed deliberately to exclude the Soviet Union, but Stalin could have negotiated to see if a deal was possible. Stalin also assumed the Americans would not intervene in Korea.

So what were Stalin’s priorities? First and foremost, security – meaning primarily military security. He had to ensure that the West did not launch an attack to destroy the Soviet Union and its satellite states in Eastern Europe. He always asked for respect and a recognition that the Soviet Union and the US were equal powers, but America was quite unwilling to concede this. Then came ideological security because he recognised that Soviet society had not developed to the point where it could resist the seductions of capitalism. This also meant walling Soviet culture off from bourgeois culture, again because the latter could contaminate the former. This applied also to science and technology, even though there was a cost to pay by avoiding contact with the world’s leading scientists and engineers, and Stalin even divided science into socialist and bourgeois science. For instance, he viewed much of Einstein’s work as erroneous and rejected Mendelian genetics in favour of Lamarckian genetics – the latter believed in the inheritance of acquired characteristics. He dismissed Freud as a pervert. Khlevniuk sees Stalin’s first priority as personal security, and all the aforementioned policies stemmed from this basic premise. If you like, Stalin was a control freak who had to control everyone and everything he encountered. It is possible to conceive of a post-war world which did not provoke a Cold War. The prerequisite was communist and capitalist worlds which had minimal contact with one another and could coexist without any meaningful interaction. The problem with this analysis is that it is not Marxist. Stalin took the view, as a Marxist, that capitalism had to attempt to destroy communism before communism destroyed it. The stronger communism became, the more desperate capitalism would be to destroy it. Hence conflict was inevitable but it must never be allowed to spiral into war.

Dr Myasnikov’s assessment is that the Soviet Union was ruled by a sick man in the years before his death. He underlines his obstinacy and suspiciousness. When did his mental faculties begin to decline? Was his obstinacy one of the reasons for the length of the Berlin Blockade? His suspiciousness would have contributed to the Leningrad Affair, the Show Trials in Eastern Europe and the treatment of Molotov, Mikoyan and others because he appears to have believed that they were conspiring against him. The last foreigner to have an interview with Stalin was the Indian foreign minister, and he noted that Stalin was doodling while he was talking to him. Doodling what? Wolves. Did he see himself being attacked by wolves or was he planning to set the wolves on others? All in all, the second nuclear power was headed by a sick leader whose behaviour was quite unpredictable.

How does one recognise a psychopath? The traits of a psychopath include lack of empathy; no conscience; being a risk-taker; grandiosity; narcissism; sexual promiscuousness; superficial charm; being manipulative; possibly becoming very violent; ruthlessness; and unwillingness to admit guilt (but some are murderers but others are not). So was Stalin a psychopath? As he ticks many of the boxes listed here, he can be judged a psychopath. Many other world leaders were also psychopaths, including Hitler, Mao Zedong, Pol Pot and Muammar Gaddafi. It is striking that among Soviet leaders after Stalin – Khrushchev (but he was a high risk-taker), Brezhnev, Andropov (but he was addicted to conspiracy theories), Chernenko and Gorbachev – none was a psychopath. This is one of the reasons why there was no world war after 1953. In Eastern Europe, the psychopath was Romania’s Nicolae Ceauşescu, but Enver Hoxha, the Albanian leader, may also qualify. Among US presidents the nearest to a psychopath was Richard Nixon, but he always knew when to draw back from nuclear Armageddon. This said, the North Vietnamese fell for his Madman act, and hence they adjudged him a psychopath.

Psychopaths are also to be found heading businesses, such as Robert Maxwell (Mirror Group), Fred Goodwin (who bankrupted the Royal Bank of Scotland) and Jeffrey Skilling (who destroyed Enron). Psychopathic tendencies help many politicians and businessmen get to the top where ruthlessness and total self-belief are often rewarded. One of their traits is not knowing when to stop expanding their empire, and this normally ends in disaster. Another trait is to see no difference between oneself and the state. Louis XIV famously said ‘L’Etat, c’est moi’ (‘I am the state’); Stalin clearly identified himself with the Soviet state and Mao also fell into this category. In 1933 a Norwegian psychiatrist diagnosed Hitler as a psychopath and warned that there was trouble ahead, but he was ignored. As yet, there is no medical cure for psychopathy.

What is socialism? The most difficult and tortuous way to progress from capitalism to capitalism.

(Czech StB officer at the last meeting of Soviet bloc intelligence services in East Berlin, in October 1988)

The answer is quite simple: one of the main protagonists, the Soviet Union, collapsed. Why?

Domestic reasons

- The Soviet Union was dismantled by the ruling elites who decided that the system was no longer worth defending. They had concluded that a post-communist world would offer them greater rewards. Hence it was not the people below who overthrew the USSR but those on top.

- The attempted coup in August 1991 failed because society had changed radically; Gorbachev thought that had the coup been launched a year and a half or two years previously, it would probably have succeeded.

- Fear of the KGB declined to the point where, in August 1991, the statue of ‘Iron’ Feliks Dzerzhinsky in front of the Lubyanka was toppled.

- The Soviet Union proved incapable of inspiring and leading a world socialist revolution.

- Karl Marx, in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, posed the question: how was it possible for Louis Napoleon to dissolve the Legislative Assembly and negate the democratic achievements of the Second Republic and become Emperor Napoleon III in the 1851 coup? The answer was simple: the Second Republic was a premature revolution because it lacked the social substructure to sustain itself. The reason, applying Marx, why the Soviet experiment failed was because the October Revolution was a premature revolution. Russia in 1917 lacked the social substructure to build communism, and Lenin’s belief that the party, as the vanguard of the proletariat, could compensate for this absence was misguided. Lenin simply ignored Marx’s warning, and Russia paid a heavy price.

- It lacked intellectual and cultural prestige.

- This was present under Lenin, but Stalin concentrated on building socialism in one country and moved from ideological conviction to military and political pressure.

- This led to opposition within and outside the USSR.

- The Soviet standard of living did not keep pace with the aspirations of the Soviet people; they could see that living standards in the GDR and Czechoslovakia, for example, were higher than in the Soviet Union; so Coca-Cola and jeans were more ideologically damaging than any capitalist propaganda.

- An inability to analyse the defects of the planned economy, which was accepted as the highest form of economic management. This led to a rash of conspiracy theories in which the malevolent influence of the US and the West was always present. Kryuchkov and Andropov were especially prone to blame Soviet economic failure on a Western conspiracy. In June 1991, Kryuchkov read out a 1977 report by Andropov to the Politburo claiming that the CIA, regardless of cost, was recruiting agents within the Soviet economy, administration and scientific research and training them to commit sabotage. Many of the Soviet Union’s current problems, claimed Kryuchkov, derived from this sabotage offensive (Andrew and Mitrokhin 2005: 489–90). Valery Boldin, Gorbachev’s chief of staff, took seriously Kryuchkov’s claim that the KGB ‘had intercepted certain information in the possession of Western intelligence agencies concerning plans for the collapse of the USSR and steps necessary to complete the destruction of our country as a great power’ (Boldin 1994: 263).

- Marxism-Leninism became wooden and was dismissed by most of the intelligentsia; when I asked a Russian once about ideology, she replied dismissively: ‘Educated people do not discuss Marxism-Leninism!’ Soviet youth (and some oldies as well) were enraptured by Western pop music.

- Gorbachev’s new thinking unleashed nationalist aspirations in non-Russian republics.

- Glasnost undermined the authority of the CPSU.

- Heavy military expenditure deprived other sectors such as education, health, culture and social services of investment. Soviet industry could simply not compete with the US in the scientific and technical race for supremacy; one example of this was the small number of computers available, even to the military. A major weakness was that innovations in the defence sector were not transferred to the civilian economy.

- The country never solved the food problem, even with agricultural investment reaching 25 per cent of the budget; enormous amounts of food had to be imported.

- Gorbachev made a fatal mistake by engaging in political and economic reforms simultaneously.

- His economic reforms were haphazard, sowed confusion, lacked coherence and clear goals.

- He wanted to make the centrally planned economy more efficient and thought that by introducing capitalist reforms he could achieve this objective; this revealed he did not understand economics.

- Rise of Boris Yeltsin and Russian nationalism in the Russian Federation.

- Ukraine’s decision to go for independence sealed the fate of the Soviet Union.

- The Russian Federation would only join a successor state if Ukraine joined it.

External reasons

- The Soviet Union could not compete economically and militarily with the US; however, Soviet military power was at its zenith when the state collapsed, but in many sectors technically it was slipping behind the US; the financial burden was simply too heavy. Reagan realised this and ratcheted up defence spending.

- The SDI programme could not be matched.

- Presidents Reagan and Bush always adopted policies which promised to force concessions out of the Soviet Union.

- Eastern Europe was a financial liability.

- Gorbachev told Eastern European leaders, in 1985, that they had to build communism on their own; there would be no more military interventions; this signalled that the Brezhnev Doctrine was dead.

- Gorbachev believed that because the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe had chosen socialism, this would never change; reverting to capitalism was inconceivable; it would mean going backwards socially.

- Collapse of communism in Eastern Europe was a shock and a bitter blow; it inspired those in the Soviet Union who wanted to see the back of the CPSU.

- The Eastern European example encouraged Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Georgia and Azerbaijan to go for independence.

- By the mid-1980s, the Soviet model had failed in the Third World; communism was often the result of military power but, in order to be sustainable, military force has to give way to consensus based on economic and social wellbeing; failure to achieve this resulted in the collapse of communist states. Efforts to copy Soviet industrialisation and the collectivisation of agriculture resulted in abject failure. The belief that the Third World was the battleground on which socialism would vanquish capitalism worldwide proved a chimera. During the Khrushchev era, the Soviet Union was involved in over 6,000 projects, not all economic. The continent which suffered the most was Africa; it is instructive that the states which received the greatest arms shipments suffered most; weapon exports to sub-Saharan Africa rose from $150 million in the late 1960s to $370 million in 1970–73 and $820 million in 1974–6, before reaching a peak in 1977–8 of $2.5 billion; during the years 1980–7, weapons exports averaged $1.6 billion annually, but fell dramatically to $350 million annually over the period 1989–93.

(Clapham 1996: 153–4)

Other reasons

- Détente was a milder form of liberation policy.

- President Kennedy’s strategy of peace and Egon Bahr’s concept of change through closer contacts in Germany and Eastern Europe bore fruit; they proposed closer contacts, information exchange and trade as ways of breaking down barriers.

- These were based on the magnet theory of liberation policy.

- The Helsinki Final Act had hidden dangers; the West could protest against human rights violations in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe; the new electronic media promoted freedom of expression and contacts.

- The Soviet Union abjured the use of force outside its frontiers; the West was not going to attack.

- Gorbachev was radically different from previous Soviet leaders.

- He took risks, and when they did not achieve stated objectives, he took even greater risks; these led to the destruction of the Soviet Union.

- Hence he can be regarded as an ‘accidental’ leader.

- If this is so, the end of the Cold War was an accident, a stroke of luck.

- Changes in perception of Gorbachev in the outside world are critically important.

- He came to be regarded as a man of principle; one who could be trusted.

- Hence arms control and disarmament treaties could be signed.

- Both sides accepted that nuclear arms could not guarantee security; in fact, they increased tension because of the lack of trust between the two sides.

- The end of the Cold War revealed it to be a classic power struggle.

- Both sides held on tenaciously to their narratives.

- Gorbachev was removed from power by the attempted coup; no Soviet successor emerged, only Russian and Ukrainian leaders who wanted power for their republics.

- Central Soviet government and CPSU authority had vanished by late 1991.

- President Bush tried to keep the Soviet Union together as he feared the loss of control over the Soviet nuclear arsenal which was dispersed over four republics; he had no influence whatsoever over the final death agony of the USSR.

- Hence it was not a change in US policy which led to the end of the Cold War; it was a change in Soviet policy; this change was so radical that it led to the breakup of the Soviet Union; it is difficult to conceive of any other Soviet leader espousing the same policies; Gorbachev conceded one point after another to the US because of his desire to create a new world but also because of economic weakness; this is particularly evident in his negotiations with Helmut Kohl, the West German chancellor.

There were two main centres

- East and West;

- It was a total contest embracing politics, economics, social, culture, science and technology, sport, music, etc.;

- Because a nuclear war could not be fought, competition moved to other spheres; this resulted in proxy wars with conventional weapons; e.g. Korea and Vietnam;

- Space opened up for other powers to act: e.g. West Germany and its Ostpolitik; China, Vietnam, the UN and the Non-aligned Movement were influenced by the main actors but were able to find room to manoeuvre.

There was no reason for the CPSU to lose power or the Soviet Union to collapse; therefore, the demise of communist power was not inevitable; it resulted from misguided policies; Gorbachev let go of the usual levers of power and tried to ‘modernise’ the Soviet Union – in other words, to make it more like the US or a Western European state; the tragedy was that neither he nor anyone else knew how to transition from a centrally planned to a capitalist economy. Had he come to power a decade later, this conundrum would have been a no brainer; copy China’s (and Vietnam’s) move to a capitalist economy, guided by the Communist Party; China revealed that a Communist Party can reform successfully a centrally planned economy by moving to a capitalist economy.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences embarked on two exhaustive studies: why did the Communist Party of the Soviet Union lose power and why did the Soviet Union collapse? The Soviet Party lost power because it departed from Leninist norms:

- Democratic centralism;

- A monopoly of political power;

- Unwillingness to use coercion to stay in power.

There is also the view that the Soviet communist culture was not robust enough to withstand Western ‘infiltration’.

Xi Jinping, in early 2013, added his judgement which can be summed up as:

- Political rot;

- Ideological heresy;

- Military disloyalty.

Political rot set in when Gorbachev began his political reforms which were much too hasty, and although they aimed at strengthening the role of the party, they had the opposite effect. Economic reform undermined the leading role of the party. An example of what Xi calls ideological heresy was the removal of Article 6 of the Soviet Constitution which afforded the party a monopoly of political power in the state. Military disloyalty presumably refers to the reluctance of the military to become embroiled in domestic security after the Vilnius events of January 1991 and another example would be the botched coup in August 1991.

In December 2013, he stated that the CPSU had made a fatal error by denigrating Lenin and Stalin, and the result of unseating the founding fathers was that

party members wallowed in historical nihilism. Their thoughts became confused, and party organisations at different levels were rendered useless.

What would have happened had Viktor Grishin, the Moscow Party leader, been elected to lead the Soviet Union, instead of Gorbachev, in 1985? Most likely, the USSR would still be in existence. He would not have embarked on political reform but would have been forced to introduce economic reform which would not have undermined the authority of the party. Given the loyalty of the KGB and the military to the party, it is difficult to see the country collapsing. Put another way, the Cold War that Gorbachev ended would still be with us.

On 24 October 1973, US forces went over to DEFCON (Defense Readiness Condition) 3, two stages from nuclear war. This was in response to Soviet threats to send an airborne force to fight on the Arab side during the Yom Kippur War. The Soviet military favoured action, but Brezhnev did not accept their advice.

On 26 September 1983, Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov was on duty in the bunker near Moscow which monitored the Soviet Union’s Oko early warning satellite system. Suddenly, just before midnight, the screen went red, and the alarm bells would have woken the dead. A satellite showed that the US had fired five ballistic missiles at the Soviet Union. Just a few weeks before, on 1 September, the Soviets had shot down a South Korean civilian airliner, killing 269 civilians, including a US congressman, as they had assumed it was a military aircraft. So tension was high.

Petrov should have passed the information on to higher command which could have set in motion a full scale nuclear alert and possibly war, but he decided not to do so because it struck him as odd that the Americans would launch an attack with only five missiles. He also did not trust the newly installed launch detection system, and the ground-based radars did not confirm the launch.

Later a satellite proved to be the culprit. It mistook the sun’s reflection off the tops of clouds for a missile launch, and the computer system which was supposed to filter out such information did not do so.

Initially, he was praised for his judgement but later reprimanded, and he concluded that the bugs found in the early warning system and false alarms had embarrassed the top brass and scientists. He is to be commended for using his own judgement as there is no telling what would have happened had he confirmed to the high command that the US had launched a nuclear strike.

Needless to say, NATO was unaware of the scare. On 2 November 1983, it launched an exercise, codenamed Able Archer 83, covering the whole of Western Europe. It simulated a conflict escalation, culminating in a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union; the scale of the exercise was interpreted by Moscow that a nuclear war was imminent. It put its nuclear forces on alert and placed air units in Poland and East Germany on alert, but the threat of nuclear war ended on 11 September when the exercise ended.

These three cases, plus the Cuban Missile Crisis, could have escalated into nuclear war. As far as one knows, they are the closest the world came to nuclear Armageddon.

In 1987, the Soviets launched a submarine exercise off the US coast, but it took the US Navy five days to detect it. In case of war, this would have resulted in US cities being wiped out by nuclear missiles.

Why were Soviet submarines so advanced and increasingly difficult to detect? John Walker headed a spy ring which had been selling US naval secrets to the Soviets for twenty years before he was unmasked in 1985, with the information being incorporated in the newest Soviet submarines. In the late 1980s, the Soviets were designing a submarine which could stay submerged for seven years.

The enormous investment in submarines resulted in repairing and servicing being curtailed, and this led to tragedy, on 6 October 1986, when the K-219 nuclear submarine sank in the Sargasso Sea, in the Bermuda Triangle, with sixteen nuclear missiles and forty-eight warheads on board. A sailor sacrificed his life to shut down the nuclear reactor and thereby prevented a nuclear explosion; most of the submariners were rescued.

The Royal Navy’s nuclear submarine fleet was much smaller than the American, and this meant it had to take more risks in shadowing Soviet nuclear subs. On one occasion, a submarine was within a few hundred yards of a Soviet sub but managed to remain undetected. An American, when asked to assess the performance of the Royal Navy captains and crews, said they had ‘balls, balls’.

What about nuclear weapons on US soil? The Defense Atomic Support Agency has revealed that between 1958 and 1974 there were several hundred ‘Accidents and Incidents Involving Nuclear Weapons’, and these ranged from the ridiculous to the miraculous.

In 1960, a nuclear war with the Soviet Union was narrowly averted after a US Air Force computer had identified a rising moon over Norway as a ‘99.9 per cent certain’ incoming Soviet nuclear missile. In 1961, a B-52 bomber broke up over North Carolina and dropped a four-megaton hydrogen bomb, but it failed to explode when it hit the ground because one switch (out of 10) remained in the safe position.

In 1966, a B-52 bomber refuelling over Spain exploded and dropped four hydrogen bombs, but they did not explode.

In 1968, a B-52 over Greenland caught fire. The crew bailed out, and the aircraft, carrying four hydrogen bombs, hit the ice at 600 mph. The explosion destroyed the USAF base and scattered plutonium over three square miles, but many bomb parts were never recovered.

Maryland, New Jersey, Louisiana, Kentucky, Texas, Morocco, Japan and RAF Lakenheath in Suffolk were scenes of further miraculous escapes.

In September 1980, in Arkansas, a Titan II, carrying a nine-megaton warhead with an explosive force three times as powerful as all the bombs dropped during the Second World War, ignited. It shot 1,000 feet into the air, but the warhead did not explode (Schlosser 2013: passim).

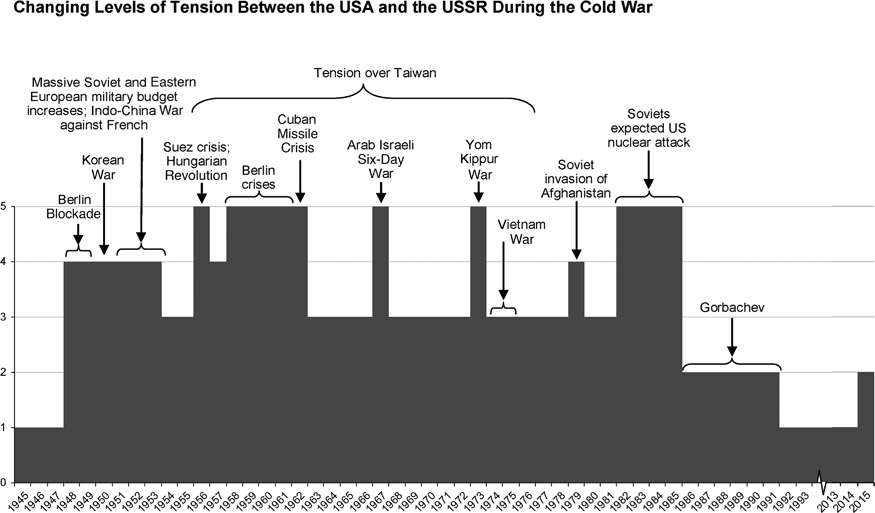

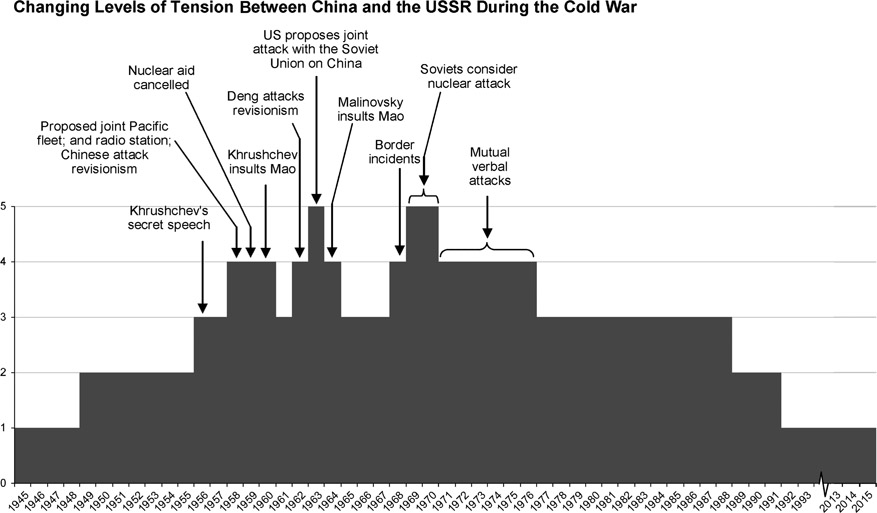

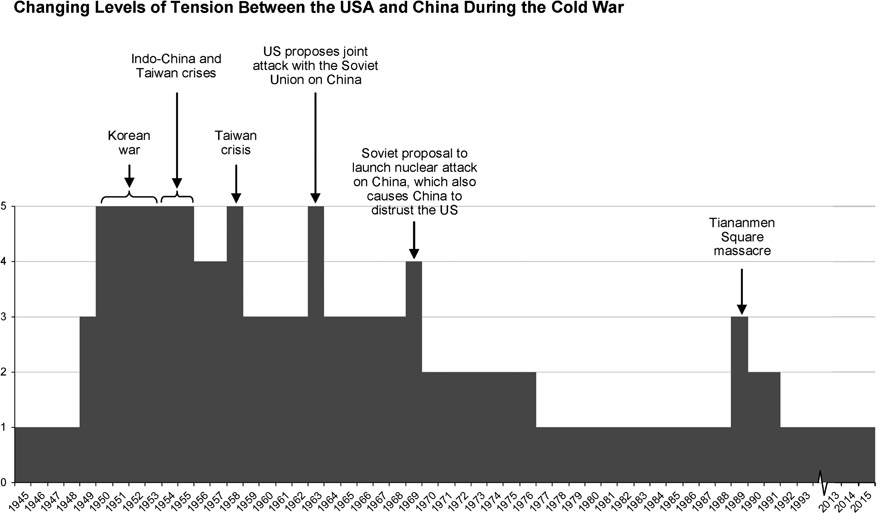

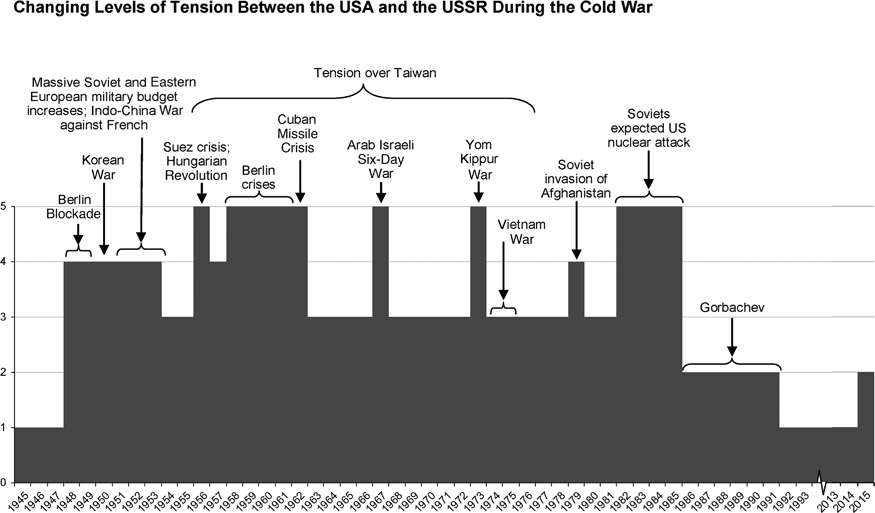

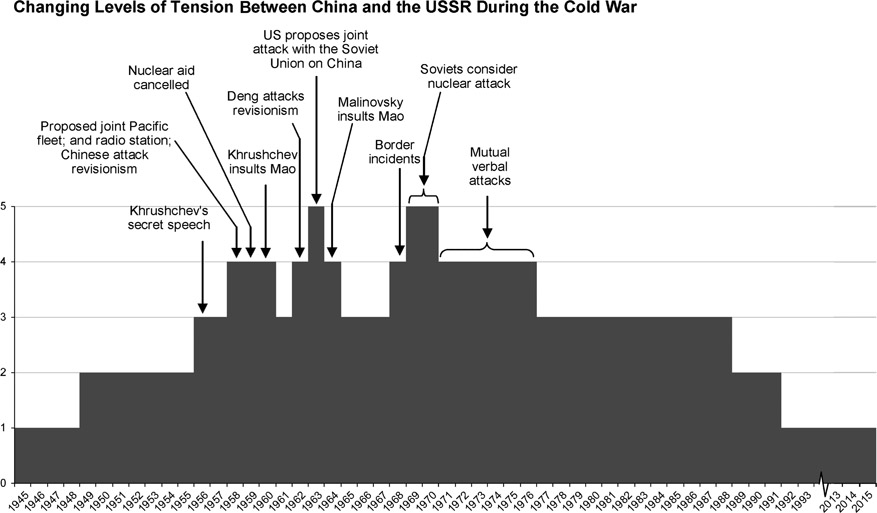

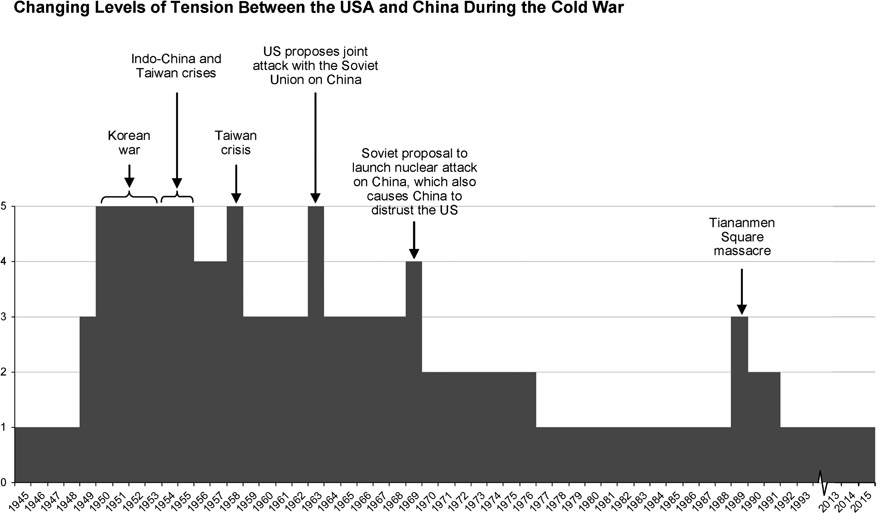

Here is the superpower confrontation presented in graphic form:

There were quite a few very dangerous years: the 1950s, 1962, 1967, 1973 and 1980–5.

The most dangerous years were the 1960s.

The most dangerous years were the 1950s and 1963.